Abstract

The purpose of this study is to employ the existing theory on crisis management and corporate branding in a service context to explore how tourism businesses in Thailand can recover from the crisis caused by the impact of COVID-19. To manage the impact of COVID-19, the concepts of crisis management from different scholars are integrated, and crisis management is divided into three phases: the Pre-Crisis, Crisis, and Post-Crisis phases. This exploratory research employs stakeholder interviews to discover the impacts of COVID-19 on tourism businesses and attempts to develop guidelines for recovering tourism businesses within the service context. Our findings indicate that a strong brand and its proper management can help firms to survive during the crisis period. Moreover, our findings highlight the importance of communication for engaging with all staff during the recovery period. This paper sheds light on how a brand is employed as a proactive strategy to mitigate the impacts of the crisis. Most brands have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and only strong brands are able to survive. Our study also adds to the limited empirical evidence on tourism business recovery during COVID-19 in the context of a developing country. From practitioners’ perspectives, trust, solid relationships, and honest communication with their business partners play an important role in survival after the crisis. Additionally, in this paper, corporate branding is conceived as a strategic tool that affects how staff and stakeholders can collaborate and unite in response to the crisis.

1. Introduction

The world is facing a major threat from the COVID-19 pandemic, which is creating havoc in all sectors around the globe. The coronavirus pandemic, better known as COVID-19, originated in Wuhan, China, before spreading to other countries around the world. The first cases were reported in November 2019, and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020. It has had and is having a huge impact on people, families, and communities. As of 13 May 2021, there have been around 161 million (161,104,567) confirmed infections around the world, increasing from 3,042,444 infections on 28 April 2020. About 3,345,813 people have died, and there are approximately 20 million active cases. The United States has the highest number of infected people with 33,586,136 reported cases, followed by India with 23,703,665 cases, and Brazil with 15,361,686 cases (Worldometers, 2021, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus, accessed on 13 May 2021).

The ongoing rapid spread of COVID-19 has severely impacted all sectors across the globe [1]. The tourism industry is one of the most sensitive sectors in any crisis and also tends to be one of the last to recover after a crisis. Consequently, Sharma and Nicolau (2020) [2] predicted that all sectors in the tourism industry would inevitably lose value, with the cruise industry being the most affected. The tourism industry is the key pillar supporting the Thai economy, which was clearly evident after the economic downturn in 2008. From the onset of the crisis, Thailand was not severely affected. This was primarily because the income from the tourism sector played an important role in driving the nation’s economy, resulting in a large number of jobs. In 2019, the tourism industry generated a revenue of THB 301 trillion [3], making it the stronghold of Thailand’s economy. Since March 2020, tourism businesses and other services in the country have been shut down following government policies and emergency measures. Governors in many tourism destinations, e.g., Bangkok and its surrounding provinces, locked down the provinces as authorized by Thailand’s government. Hotel and travel businesses have been closing down and facing losses. Tourism industry workers have inevitably been affected by this crisis in terms of going unpaid or losing their jobs. This crisis has affected the whole tourism supply chain, including international business partners who collaborate in inbound tourism. Given the significance of this sector to the Thai economy and other countries that heavily rely on this sector, it is important to devise a strategy for recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

During a crisis, survival is the key issue for all businesses. Many businesses learnt from the SARS epidemic of 2002 and realized that crisis management, i.e., the concept of developing a recovery plan, is vital [4,5,6]. Many scholars (e.g., Pine and McKercher, 2004 [7]; Henderson, 2003 [8]; Kim et al., 2006 [9]) published studies on the recovery of tourism businesses from SARS. For example, Pine and McKercher (2004) [7] studied the recovery of tourism businesses in Hong Kong from 2002 to 2004 and highlighted that hotel businesses implemented many tactics to reduce costs and expenses, e.g., closing swimming pools and spa services, limiting elevator use to reduce electricity costs, and so on. This is in line with Kim et al.’s (2006) [9] recovery plan for Korean five-star hotels after the SARS crisis. They suggested cutting costs and an emphasis on increasing human capital development during the period.

Although COVID-19 is an ongoing crisis, there is already a small number of published projects that attempt to explore potential recovery plans. Mulder (2020) [10], for example, proposes focusing on tourists who are potentially immune after successfully recovering from COVID-19. However, this could be complicated by the new evidence suggesting that people can be re-infected with COVID-19. The tourism industry, which is extremely sensitive, is currently sailing through uncertain waters, and this is exacerbated by the fact that it is hard to predict when the COVID-19 pandemic will end [4]. However, crisis management theory in this situation can help businesses to deal with the ongoing disruption that is threatening their existence.

Brands tend to be significantly affected during a crisis if not properly managed, and it often requires significant resources to ensure that a brand survives during a period of adversity. Iglesias et al. (2020) [11] employed the concept of corporate branding to manage risk because it can increase customers’ trust and reduce the perceived risk [12]. Recently, Wang et al. (2020) [13] demonstrated that the brand image could reduce tourists’ risk perception from a crisis. Many scholars, such as Balakrishnan (2011) [14], Hegner et al. (2014) [15], Li and Wei (2015) [16], Falkheimer and Heide (2015) [17], have studied how firms can rescue brands from crises. However, there is little interest in exploring how a brand can be used as a tool to help tourism businesses recover from crises. This paper attempts to address this research gap by exploring how a strong brand and its proper management can help tourism businesses survive during a crisis period. To respond to the COVID-19 crisis, tourism businesses should analyze the situation and proactively search for solutions. Tourism businesses also need to estimate whether they are in an intermediate phase or relief phase in order to plan effective recovery strategies. This study, therefore, aims to combine knowledge of crisis management and brand management in tourism businesses in order to devise a recovery strategy in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to Zenker and Kock’s (2020) [1] call for new crisis and disaster management research, this paper hopes to shed light on the following research question:

How can a brand be employed to manage the crisis caused by COVID-19?

This research employs existing theories on crisis management and corporate branding in the hospitality context to explore how tourism businesses in Thailand can sustainably recover from the COVID-19 crisis. The findings of the paper will greatly benefit practitioners in the tourism sector in guiding their businesses on a path of recovery both during and after the crisis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses the two key theoretical concepts: crisis management and brand management. Section 3 outlines the methodology and data collection. Qualitative inquiries through interviews were employed for data collection. These data were used to develop a recovery plan for the hospitality sector. Section 4 presents the empirical findings from the interviews. Finally, Section 5 concludes this study by providing a set of recommendations in line with concepts of crisis management and corporate branding theory.

2. Literature Review

Figure 1 depicts our proposed approach, which is guided by brand management and crisis management theories. The rest of the section covers literature around these key theories. Section 2.1 discusses the impacts of crisis and recovery strategies on tourism businesses; Section 2.2 explores crisis management, and Section 2.3 presents the role of brand management during the crisis.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model.

2.1. Impacts of Crisis and Recovery Strategy of Tourism Businesses

The tourism industry is sensitive to threats (e.g., disasters, pandemics, terrorism, economic crises, and so on), and the impact of these threats affects wider economic, social, environmental, and cultural aspects. In 2002–2004, the SARS epidemic spread from continent to continent, infecting more than 8000 people [7]. Hong Kong was one of the nations affected by SARS. It relies heavily on tourism, and the SARS epidemic resulted in arrivals in Hong Kong International Airport declining by approximately 80%, unemployment increasing by 8.6%, and the occupancy rate declining to just 10–20%. This led to significant cost-cutting and many staff going unpaid. In response to this crisis, the Hong Kong Government spent nearly HK$1 million on rebuilding the image and drawing tourists back, while tourism businesses provided incentives such as free flight tickets, hotel offers, discounts, and so on [7]. As a result of cash flow problems, hotel owners needed help and financial assistance from the Government to support their businesses. For example, a one-year waiver of sewage expenses and trade effluent charges reduced property rates and suspension of the employer [7,9]. Hotels also took the following initiatives to deal with the crisis in Hong Kong and Korea, as reported by Pine and Mckercher (2004) [7] and Kim et al. (2006) [9]:

- Cost-cutting by closing down swimming pools, fitness centers, and spas;

- Reducing electricity costs by using fewer lifts;

- Expanding the repayment period for loans to improve cash flow;

- Networking with other businesses, e.g., airlines, travel agents, and so on;

- Using marketing strategies, e.g., offering discounts (e.g., 30–50% program), advertising to boost tourists’ confidence;

- Implementing HR tactics, e.g., offering leave without pay, human capital development, cutting down temporary staff, communicating with staff.

Kim et al. (2006) [9] employed crisis management contingency concepts to explore the SARS crisis in 2003 in Korean five-star hotels. The strategies that Korean hotels employed were similar to those reported by Pine and McKercher (2004) [7], i.e., cost-cutting and human capital development. An additional strategy related to health and safety, which Kim et al. (2006) [9] highlighted, played an important role, as it affects tourist travel decisions. Tourists are likely to cancel their trips if there is uncertainly and high perceived risk, such as a political crisis, war, pandemic, or disaster [4,9]. Toanoglou et al. (2021) [18] have studied tourists’ perception risk toward tourism by exploring the effects of media coverage, governance, tourism behavior, and the COVID-19 in different countries. They demonstrated that tourists were influenced by the media for perceiving the risk of the crisis. To respond to the crisis, tourism businesses can develop collaboration among their stakeholders [8,19,20] and employ this as an effective strategy during the crisis.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing around the world, various scholars, such as Mulder (2020) [10], Riley (2020) [21], and Jamal and Budke (2020) [22], have demonstrated guidelines for managing this crisis. For example, Mulder (2020) [10] proposed a COVID-19 recovery strategy for the tourism industry and highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on the economic situation. Riley (2020) [21] recommends that tourism businesses target tourists who already have antibodies. However, this recommendation is based on tourists’ concerns regarding health and safety. Jamal and Budke (2020) [22] propose reacting to COVID-19 and planning recovery schemes by learning from past pandemics. Rodríguez-Antón and Alonso-Almeida (2020) [23] provide a case study from Spain wherein hotel rooms were utilized to support medical operations, although they do not go into detail. The discussion presented in this section shows that tourism businesses have survived previous outbreaks by managing the crisis effectively with the support of the stakeholders. In the next section, we elaborate on the concept of crisis management in managing the recovery of the tourism sector.

2.2. Crisis Management

With a view of managing the impact of COVID-19, the concept of crisis management from different scholars [20,24,25,26,27] is explored. Crisis management is classified into three phases: Pre-Crisis, Crisis (with three sub-phases: emergency; intermediate; relief), and Post-Crisis (with two sub-phases: recovery; learning process). Mao et al. (2010) [28] recommended the catastrophe model or CAT Model to analyze the data regarding the SARS pandemic. With the application of the CAT Model, Mao et al. (2010) [28] developed two promotional strategies, i.e., a macro strategy for increasing confidence and safety and a micro strategy for reducing the perceived risk of travelling.

Although many scholars think of a disaster as a form of a crisis, disaster and crisis are different: a disaster is an unforeseen event that causes damage or ruin, while a crisis is an unpredictable event, the effects of which provide uncertain results [29]. Tourism businesses are urged to redesign their organization to respond to crises [30]. Kim et al. (2006) [9] and Pforr and Hosie (2008) [19] do not only focus on management and marketing but also human resource management in crisis management. In order to respond to a crisis, they highlight the need for managers to incorporate different aspects into their planning process, e.g., socio-cultural, economic, political, historical, physical, and so on. Additionally, they argue that crisis management should be treated case by case.

To manage a crisis, Fink (1986) [24] proposes a crisis management model that can be divided into the prodromal stage, the acute stage, the chronic stage, and the resolution. However, Fink’s (1986) [24] crisis management model does not focus on proactive action in response to the crisis. Other scholars, e.g., Roberts (1994) [25], Ritchies (2004) [20], and Faulkner (2001) [26], focus on proactive management by preparing before the crisis until the recovery. Faulkner (2001) [26] developed a multi-stage process to cover different periods of the crisis, known as the Tourism Disaster Management Framework (TDMF). It involves different stages: the pre-event, prodromal, emergency, intermediate, recovering, and resolution stages. However, Faulkner’s [26] framework tends to be suited to natural and people-made disasters rather than pandemic events. In this direction, Hosie and Smith (2004) [27] proposed an additional model: the PPRR (Prevention, Preparation, Response, and Recovery) crisis management model. These models tend to overlook the action after the crisis, i.e., learning from the crisis [31]. The output from the learning process plays an important role, as it acts as an input in the proactive stage to enable all related stakeholders. This requires input from different disciplines, including marketing, management, and human resource management [19].

A crisis is an unexpected event that negatively affects a particular organization, industry, or country [32]. Therefore, it is difficult to accurately predict the beginning and end of a crisis. Businesses need to be well prepared for future crises. Applying the concepts of crisis management, crisis management can be classified into three phases: Pre-Crisis, Crisis, and Post-Crisis. Pre-Crisis is a proactive stage similar to Faulkner’s (2001) [26] pre-event stage. All stakeholders should be prepared for a possible crisis, whether it is a disaster, terrorism, a pandemic, etc., by learning from past events. A crisis is a period that emerges in three sub-phases: the emergency phase, in which the crisis begins and people cannot deal with the event, so all damages need to be explored to provide initial support; the intermediate phase, in which people can cope with the situation, so the crisis needs to be controlled and managed to mitigate its impacts; and the relief phase, in which the situation is approaching normality again, and the damage and impact should be discovered to prepare for the recovery. The first two phases (Pre-Crisis and Crisis) are short-term responses to the crisis, which are necessary for stakeholders in order to relieve the negative impacts. The final management phase is the Post-Crisis phase and can be divided into two sub-phases: the recovery phase, in which the situation is normal and all parties need strategies to recover all damages; and the learning process phase, in which after-action research is conducted in order to manage knowledge and resources as regards crisis management.

In the Pre-/Post-Crisis phases, communication is one of the most critical strategies for managing the situation [33]. Crisis communication to the public and tourists is required by organizations to ensure that all stakeholders can be confident in the health and safety situation after the crisis [34]. It is necessary to communicate with internal staff to share information and drive collaboration through the crisis. Mazzie et al. (2012) [35] reported that good internal communication plays an important role in driving staff collaboration when recovering from a crisis. ‘Trust’ in the organization or company also increases after staff receive accurate and adequate information, and risk or damage from COVID-19 can be reduced [36]. This also includes government policy about communication during the crisis that affected tourists’ perception risks [37]. On the other hand, good communication also increases the chance of tourists perceiving risks from the crisis [38], which leads to our first proposition:

Proposition 1.

Communication plays an important role in engaging all staff for collaboration in the recovery period.

2.3. Brand Management in the Crisis

Tourism businesses require collaboration with travel agencies, especially international agencies because they have access to international tourists: an important tourism market [39,40,41]. With the high levels of competition in the tourism market, retailers can consider offers from different wholesalers or tourism businesses and tend to be less loyal to a particular brand [42]. Certain tourism businesses encourage sustainable growth by signing contracts with their partners, e.g., travel agencies abroad. Contracts can ensure the long-term success of tourism businesses by continuously providing tourists [43]. However, Shen et al. (2019) [43] state that trust is one of the most important aspects, along with a contract, for creating a long-term relationship. To create a relationship in the tourism industry, customer relationship management or CRM is employed as an effective strategy to increase sales and profit [12,44].

Brands have been gradually shifting in terms of meaning and importance, e.g., ownership [45], brand relationship [46], icons [47], and culture [48]. With the complexity of brand management, there are many stakeholders related to a brand and corporate identity [11,49]. There is an overlap between brand and corporate identity, which relates to the company owner, employee, and corporate culture [49]. Iglesias et al. (2020) [11] extended the study of corporate branding, expressing how corporate branding increases customer confidence. However, Balmer and Wang (2016) [50] extended the roles of a brand from being a name or logo to the strategic direction of the organization. Therefore, in this study, the concept of corporate branding is integrated with crisis management to provide guidelines for tourism businesses recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

One issue related to brand management from the perspective of crisis management is that a crisis is an event that can damage a company’s reputation, profitability, business growth, and survival [51]. Firms need to rehabilitate the brand after the crisis [14,15,16,17]. Balakrishnan (2011) [14] explored how firms can manage brand burn within the tourism industry during a crisis. Although crises in the tourism industry rarely occur, e.g., terrorism, epidemics, war, and so on [14], they affect tourist attitudes towards and confidence in travel [4,9], especially epidemics, which cause tourists to focus on ‘health and safety.’ Therefore, the recovery period for the tourism sector may be longer than for other sectors, as it takes time to rebuild confidence among tourists.

To manage a brand crisis, Balakrishnan (2011) [14] integrated crisis management models from different scholars [52,53] and divided the crisis management model into three stages: the prodromal stage, the crisis, and the audit stage. Balakrishnan’s (2011) [14] model begins with proactive action in preparing for future crises. However, crises are not only caused by disasters or external events; they can also emerge from operational failure. Li and Wei (2015) [16], Falkheimer and Heide (2015) [17], and Hegner et al. (2014) [15] focus on brand crises, which tend to emerge from business operations. They aimed to explore how a firm can manage the negative effects related to brand image and brand reputation. This evidence demonstrates that the brand crisis literature tends to focus on business crises or financial crises, but there is little interest in how a brand can recover from the crisis.

After the disaster in 2011, the destination brand was one of the essential factors in the recovery of the Japanese tourism industry [54]. The study demonstrates the positive effect brand love has on tourist revisit behavior. Sreejesh et al. (2018) [55] show that brand love can create an emotional bond between customers and the brand, which leads to repeat buying behavior. Han et al. (2020) [56] support the findings of Wang et al. (2020) [13] by employing CSR to increase the corporate image and thus build tourists’ confidence during the crisis. However, in certain circumstances, a brand can be damaged after the crisis and requires a reform strategy; therefore, rebranding is an alternative way to recover brand reputation by developing a new brand identity and positioning [57]. Han et al. (2017) [58] report that a brand can manage the crisis through honest communication with the public. The social network is a strategy to strengthen the relationship between customers and the brand. However, employing a brand as a crisis management strategy is a proactive strategy that requires a long-term commitment from the management. Other scholars tend to demonstrate short-term tactics to manage crises. This leads to our second proposition:

Proposition 2.

Businesses with a strong corporate brand are capable of quickly recovering from crises.

The key literature used in this study covering the main theoretical perspectives are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Literature.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

To reflect how tourism businesses in Thailand can manage their recovery from this crisis, this study used an exploratory research design to understand the crisis within the tourism industry. Qualitative research was employed to collect data from stakeholders in Thailand’s tourism industry, including hotel owners, management teams, tour guides, tourism organizations, academics, and so on, to bring together multiple perspectives on the crisis. In total, 12 interviews were conducted between May and October 2020 (see Table 2). The interviewees participating in this study were from tourism businesses in the Northern, Central, and Southern areas of Thailand. One of the interviewees was a senior officer in the International Office of the Tourism Authority of Thailand, who provided additional perspectives from outside the country. All the interviews were conducted through an online meeting platform (Zoom and Skype) due to the ongoing pandemic. Each interview lasted approximately 40 min. Each interviewee was informed about the project, asked to sign the consent form electronically, and asked to share information and their perspectives on this crisis. They were asked about the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on businesses and the industry, including recovery strategies involving their stakeholders. Researchers also contacted various informants by mobile phone for follow-up and to ask additional questions. The informants were asked to answer the following questions:

Table 2.

Informants’ characteristics.

- What impact has the COVID-19 pandemic had on your hotel or business?

- What are the guidelines for managing the impacts in terms of business survival?

- How do you manage your tourism agents in Thailand and abroad?

- How do you integrate problem-solving into policy planning in Thailand?

- How will tourist behavior change after the COVID-19 pandemic?

The data collection began with us asking permission from each informant before they electronically returned the signed consent form. The research aims and questions were briefly explained to informants to demonstrate how they can contribute to this study and the tourism industry. All the interviewees had more than 10 years of experience in the tourism industry and were able to provide rich data regarding the recovery strategy from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, in order to triangulate the data, participant observations with the tourism stakeholders in the destination were conducted in January 2021 through a formal meeting and conferences in Krabi province: a popular destination in Thailand. Participant observations were employed during the meetings with Krabi tourism stakeholders by informing the project and discussing crisis management. Data from interviews were discussed with tourism stakeholders during the participant observation in order to confirm the results.

3.2. Data Analysis

To analyze and interpret the data, thematic analysis was employed through the iterative process [59]. Interview data were transcribed and inscribed into the transcript format. All transcripts were read several times by three authors with academic perspectives. Additionally, practitioner perspectives were also added into the data analysis process to provide a better understanding of the data from an insider’s point of view. Codes were assigned and reread to cut the duplicate codes. All codes were reiteratively read to classify themes and meaning, according to the work of Thompson (1997) [60]. As with the coding process, all themes were reconsidered until the iterative process was complete. All the authors were assigned to consider all themes and meanings to triangulate the data. All the data were then employed for discussions to integrate the data, the theory, and the experiences within the tourism industry in order to develop a recovery strategy. Practitioner perspectives and existing theories on crisis management and corporate branding within the service context were utilized during data analysis.

4. Results

The findings of this study are based on a review of the literature and secondary documents and semi-structured interviews with 12 stakeholders from the tourism sector in Thailand.

4.1. The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism Businesses in Thailand

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the Thai tourism business ecology has been hibernating, and all activities related to tourism and hospitality have been forced to stop in line with the government and provincial emergency measures. However, despite the support that the government has provided, tourism businesses are still worried about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The knock-on effect for the economy has created a chain reaction, and tourism businesses are struggling due to a lack of income and the inability of their debtors to pay them back. This was evident during the interviews, as one of the informants (P1) mentioned

“… we do not only run this resort, but also other services with different partners; e.g., airlines, ferry, and other agencies. We would like to collect our debts, but all of them are in the same situation …”.

Another informant (P2), a tour business owner, stated

“… We don’t have any customers. I don’t know when this crisis will end, but as we know, our international partners are also in crisis. No one gets the exception …”.

This was also echoed by a tour business owner who is also a tourism organization representative (P3), who further stated

“… most effect is on economic. It is temporarily close. As an outbound business, we got a deposit and had to pay forward to our partner aboard, it was non-refundable …”.

It is evident from the quotes that various partners in B2B chains in this tourism sector are facing difficult times as a result of COVID-19. As mentioned by a Hotel Owner (P1), Tour Business Owner (P2), and the tourism organization representatives, the current situation in the tourism industry is critical. Businesses have been shutting their doors without a reopening date, but they are still incurring business expenses, e.g., maintenance, refurbishment, electricity, and so on. Therefore, in this situation, the likely survivors will be the strongest businesses, who can afford to shut the business down. The following quotes by a Hotel Owner (P1), a Hotel Manager (P7), and an Academic (P4) serve as good examples of the situation:

“… no one would like to travel at this time. We cannot rely on others. Tourists don’t trust us, and we cannot trust them. Our international tour agents are not confident to bring tourists across the country …”(P1)

“… everyone is fearing … although Chinese tourists would visit Thailand, they are still infected in China … Other Asian tourists would not visit us …”(P7)

“… we are facing a new lesson in the tourism industry. We are living with fear. Tourism will come back if we can beat our fear …”(P4)

From the Hotel Owner’s (P1) perspective, one threat to the tourism industry is the lack of tourist movement. In this situation, tourists like to stay at home rather than visit different places, as they would normally do. Fear plays an important role in travelling and, in the current situation, it is a direct impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. To reduce these effects, collaboration from all stakeholders is necessary in order to mitigate the fear. This involves responsibility and care, communication, preparation, and so on [22]. Even though the tourism industry went through the SARS crisis in 2002–2004, various businesses are struggling in this difficult period because the COVID-19 pandemic is different. The following quote reflects COVID-19′s impact on the tourism business:

“… it likes tap water with high pressure, and suddenly stops … in the middle of the tourism season. It’s our new experience of 27 years in business … We face the problem to deal with this crisis.”(P5)

One of the Hotel Owners (P5) stated that this crisis is different from others because it happened without warning. It is an emergency as in other crises [25,26]; however, this crisis is having a dramatic impact on the economy and society by changing the culture, society, and way of life. All tourism services have to be redesigned from the tourists’ perspective, taking into account their journey from their homes to tourist destinations, their experience, and their behavior. Tourism businesses have to be able to predict the new tourism patterns in order to design new services and to communicate with their travel agencies abroad to build trust and confidence.

4.2. Short-Term Response to the Crisis

Tourism businesses faced several epidemics/pandemics in the past, and they learnt a great deal from pandemic crises such as SARS, Ebola, bird flu, swine flu, and so on; however, as stated by Pforr and Hosie (2008) [19], crises need to be managed case by case due to the particular conditions. With the short notice of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism businesses did not have time to prepare for the severe impacts involved in temporarily closing the business and suspending all tourism activities across the globe. To respond to this crisis, tourism businesses in Thailand requested that staff leave without pay.

4.2.1. Feeding the Business

Adaptation to the environment is a natural human instinct. To slow down the damage, some businesses have adapted since the outbreak of COVID-19. Cutting all costs is one of the basic tactics that tourism businesses can employ during the crisis [7,9], but to survive, tourism businesses need to generate income during the crisis from existing assets. The following quotes were tactics for sustaining the businesses during the crisis:

“… all services are shut down, but our business needs to run further. Therefore, we have adapted our food and beverage department to do a catering business. We get good results because of our services, professional, and reputation …”(P6)

“… the adaptation is a way out; for example, some hotels operate in food delivery market because they have the better competitive advantage in staffs’ skills, food and drink expert, and charm of hospitality than the typical food and restaurant in the market. Hotel businesses can provide premium services. With the reputation of the hotel, competition with competitive price can support the business survival, and also staffs …”(P3)

The statement above also supports our second proposition (Proposition 2): a strong corporate brand/reputation helps firms to quickly recover from the crisis.

4.2.2. Preparing to Reopen

Although hotel businesses have to close down, all amenities need to be maintained in good condition. Therefore, some staff leave, while gardening and maintenance staff, for example, remain. The following quotes were from the business owners on how they prepare for reopening:

“… we keep some staffs to take care gardens, and also to do maintenance and refurbishing jobs. When this crisis is gone, we must ready to reopen …”(P1)

“… during this time, IT and digital tools are necessary for our company. I don’t need too many staffs. We have no income; therefore, most of our staffs are leaving without pay. After the crisis, we will use IT as much as we can …”(P2)

As seen from the practitioners’ perspectives on crisis management, reactive tactics can be used by tourism businesses in order to reduce the possible losses, sustain the business, and prepare for running a business after the crisis.

4.2.3. Ensuring Health and Safety

Additionally, the service ecology for tourism businesses is changing. Instead of reacting to the crisis, tourism businesses can be proactive by designing their service processes to ensure business partners and tourists are well informed about hygiene, health, and safety. The following quotes from informants place stress on designing the service encounter:

“… it is not only hotel businesses to change, but tourists also need to concern about social distancing and to avoid the crowd. For our business, we can adapt social distancing with our services and amenities; e.g., making a distance of sunbed, serving A la carte-breakfast instead of buffet breakfast …”(P5)

“… we are working closely with the local community members who join us as tour operators to prepare amenities and services; e.g., restroom, bedroom, dinner, and so on, to provide good sanitary …”(P9)

“… we inform community-based tourism to prepare health and safety procedures, and private tourism activities …”(P12)

“… we worked hard to be certified the SHA [Amazing Thailand Safety and Health Administration] as required by the Tourism Authority of Thailand, for reopening our business …”(P6)

Regarding P6, a hotel owner, an SHA certificate can be employed to communicate with the public, especially tourists, in order to build trust among the stakeholders.

4.2.4. Building Trust and a Relationship with a Business Partner

It is estimated that the tourism industry will recover within 18 months [61]; therefore, tourism businesses need to build trust and a relationship with their tour agencies abroad. Firstly, tourism businesses can continue to maintain open lines of communication with their partners. The following quotes show that businesses strongly believe in building relationships with partners to secure business after the crisis.

“… the recovery period depends on how the country can control the outbreak of the COVID-19. Domestic tourists will be the first one to travel. Outbound tourism needs longer time, might be June 2021 … we still make contact with an agent aboard, updating the lockdown measure; therefore, we keep informing our partners to aware of our situation in Thailand …”(P1)

“…we know that our partners are in crisis as we are; therefore, what we can do to help each other, we will do. We give them back their deposits, although we have to take all expenses, it’s for the future …”(P2)

“… decision making to travel will be shortened because of the uncertain situation as seen from this crisis. Hotel business needs to reduce the risk of business partners [tour agency aboard] by refunding the deposits if there is the crisis...”(P4)

All of them emphasize the relationship with their travel agencies that can supply customers after the crisis. This will affect the long-term creditability of the business. However, another factor for travel after COVID-19 is fear. Although this refers to tourists’ fear of travelling abroad, tour agencies play an important role in communicating and persuading them to travel abroad again. One of the tour business owners (P9) stated that they are continuously communicating with travel agencies abroad regarding the preparation and the readiness of the local community. Therefore, tourism businesses need to create an environment of ’trust’ in relation to travelling in Thailand, in which the safety and health of tourists is a priority, as is evident from the quotes below:

“… tourist behaviour after the outbreak of the COVIO-19 will be a small group or private tour with friends or family members. This group is expected to be the first tourists to travel, and tour business can present a tour guide’s health report to ensure health and safety …”(P6)

“… health and safety will be additional issues for the tourism business. Hotel needs to plan for health and safety policy, not just only life and possession policy …”(P1)

“… travelling with family for one day trip or staying overnight in the resort with a private group is possible because we trust who we are going with … all services should be private …”(P8)

“… a group of revisiting tourists will be the first arrival. Keeping existing tourists is one of emergency strategy by emphasizing on convenience, sanitary, and safety … Furthermore, we need to communicate and do PR to keep the relationship with the partners …”(P10)

In line with the Tour Business Owner (P3) and Hotel Owner (P1), another Hotel Owner (P6) suggested that the development of a screening policy for staff and guests will be essential. It is a strategy to manage the fear of tourists, similar to the tour agency’s information regarding health and safety. As stated by a senior official from the Tourism Authority of Thailand (P10), tourism businesses need to develop a communication strategy with business partners and existing tourists. However, internal communication is also required to create ’trust’ within the business, as highlighted by a Hotel Manager (P7), “… we contact hotel staffs every day through the social network for expressing our sincerity to survive together…”.

4.2.5. Reorganization for the Future

During the crisis phase, tourism businesses cannot rely on old strategies because this crisis has had an impact on the business ecology and tourist behavior; therefore, they need to prepare a strategy for after COVID-19. One informant (P11) mentions that “…we need to be smart and small by employing IT in our operation, and also developing multi-task skills for our staffs …”.

In reference to the tourism market after COVID-19, one Tour Business Owner (P3) mentioned that “… tourists have various choices, and they do not trust any businesses; therefore, the credible service providers are eligible to be tourists’ best choice …”. Therefore, tourism businesses need to provide brand identity in terms of service quality, procedure, and assurance.

5. Summary and Discussions

In summary, tourism businesses not only need to reactively respond to the emergency phase of the crisis, but they also need to proactively respond in order to prepare to reopen after the crisis. However, tourism businesses in Thailand need to develop a communication strategy for delivering confidence in health and safety provisions and convenience for their customers. In doing this, all stakeholders, including local community members and internal staff, should be part of this campaign. It is evident from the interview data that communication strategy plays an important role in engaging all staff in collaborating in the recovery period, thus supporting the first proposition (Proposition 1). Moreover, interviewee participants also supported the second proposition (Proposition 2) that a strong corporate brand helps the organization quickly recover from the crisis. The next section discusses the theoretical and practical implications of this study.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

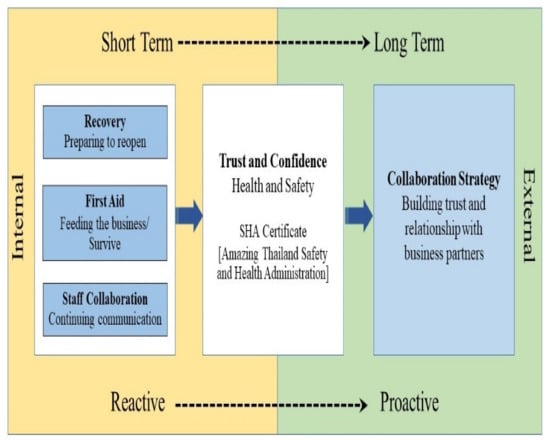

This paper adds to the limited studies concerning the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry by exploring new crisis and disaster management approaches [1]. The study attempts to achieve this through the theoretical lenses of crisis management and brand management. This paper sheds light on how a brand is employed as a proactive strategy to mitigate the impacts of a crisis. Most brands have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and only strong brands are able to survive. This study employed the concept of corporate branding as a strategic tool [50] in the context of the pandemic crisis. During the crisis, a brand should be employed as a proactive strategy for managing the risks related to the crisis/disaster. As seen from the tourism industry in Thailand, businesses with a strong brand have various opportunities to mitigate the impacts of the crisis. As can be seen from Figure 2, in the short term, internal branding is a reactive tactic to keep businesses stable, i.e., sustaining businesses with flexible services, preparing all facilities to reopen, and building collaboration among staff [62,63]. It is the crucial process of co-creating the collaboration among staff for surviving during the crisis. On the other hand, a medium-term tactic is to build trust and confidence in the service and brand. It is one of the important corporate brand attributes which can strengthen the brand identity and consumers’ confidence toward the brand [50]. Finally, the long-term strategies of co-creating a collaboration strategy and maintaining clear and open lines of communication with business partners play an important role as a proactive tactic to reduce future risk. The analysis of the interview data shows that informants tend to focus on the emergency and the short-term situation in terms of a reactive strategy. To respond to the crisis in the long term, businesses need to change their business strategy by placing emphasis on a proactive strategy. It is in line with Duarte Alonso et al. (2020)’s [64] active strategy, which international hospitality businesses have employed to cope with the crisis resiliently. From the etic perspective [65], informants are also concerned about a long-term strategy to deal with the crisis. As noted by other scholars [7,8,9], cutting costs is a basic tactic for tourism businesses in Thailand to respond to the crisis; however, as mentioned by Pforr and Hosie (2008) [19], each crisis requires a particular strategy.

Figure 2.

The recovery strategy.

This paper demonstrates how tourism businesses in Thailand can deal with the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. First, in order to deal with the crisis, businesses need to overcome cash flow issues due to the business closing down by adapting the existing staff to run the business, e.g., catering. Reputation and professional services play an important role in sustaining businesses. These are organizational changes, as mentioned by Radic et al. (2020) [30]. Additionally, employee cooperation and solidarity are key aspects of tourism business survival. Secondly, to survive after the crisis, tourism businesses need to rely on tour agencies abroad; therefore, trust and relationships together with honest communication are strategies for building long-term sustainability. Finally, as mentioned by Pforr and Hosie (2008) [19], crisis management should not only focus on businesses, partners, and staff but should also include local community members who participate in tour operations. On the other hand, all stakeholders should be included in the co-creation process of corporate branding [50]. This is also in line with Hao et al. (2020) [66], who explored how hotel businesses in China can create confidence through collaboration with other partners. These aspects are key survival factors for tourism businesses during the crisis and are a strong component of corporate branding [14,50]. In summary, previous studies focus on how firms can rescue brands from a crisis; however, our study highlights how a brand can be a tool used to recover a tourism business from a crisis.

To create trust and a solid relationship with tour agencies, tourism businesses in Thailand can employ the concept of corporate branding (see Balmer and Wang, 2016 [50]) and establish honest lines of communication, because ’trust’ can increase customers’ confidence during uncertain times [67]. This requires the co-creation of internal branding [68] and stakeholder branding [50,69]. Rogerson (2021) [70] has also demonstrated how the trust and confidence of domestic tourists are short-term strategies to sustain the financial situation of tourism businesses in South Africa during the crisis. Businesses need to drive a self-reliant strategy for surviving in the long term by co-creating trust with stakeholders [64]. Therefore, to drive the long-term response to the crisis, tourism businesses have to emphasize corporate branding as a strategic direction [50], which requires the solidarity of all members of staff in order to create a strong corporate brand identity [11] in terms of reputation, professional services, trust, and relationship. These aspects allow tourism businesses to implement flexible tactics during the crisis. Additionally, branding is also able to reduce tourist misperception as regards warning systems or measures [71], which tend to create unnecessary fear after the crisis.

5.2. Practical Implications (Recommendations)

This paper provides implications for marketing managers in managing the crisis caused by COVID-19 in many ways. First, corporate branding should be emphasized as a proactive crisis management tool (see also Balmer and Wang, 2016 [50]). The management should understand the impacts of the crisis, which can be divided into different stages. In this study, we found that ‘trust’ and ‘relationship’ together with ‘honest communication’ play an important role in creating customer confidence, and they require a co-creation period. Additionally, managers should realize that there are multiple stakeholders involved in the corporate branding process [11,50]. Therefore, corporate branding requires the active participation of stakeholders to co-create a brand, and the stakeholders must be aligned in the same direction. Within the context of the tourism industry, tourism businesses must be able to co-create confidence in the corporate brand; thus, customers and travel agencies abroad will have faith in the ability of the business to recover from the crisis.

Second, an important stage in crisis management is the crisis stage. Herein, the impacts can negatively affect brand reputation, business revenue, and, especially, cash flow. To respond to this phase, managers need to understand the situation and the capacity of the business in order to reorganize services to sustain the business during the crisis. In doing this, the management needs to focus on internal branding [72] and implant it in the employees’ mindsets. The management should co-create employee engagement, which is an important aspect of organizational culture. To co-create a corporate brand, the management needs to facilitate the communication flow with employees and other stakeholders related to tourism businesses, both during the crisis and in the non-crisis period, via social networks (e.g., Line, Facebook, Workplace, and so on).

Thirdly, during unpredictable events, managers need to be sensitive to external threats and be able to adapt the business strategy to cope with the crisis. As found in this study, ‘first aid’ is a reactive strategy to mitigate its impacts in the short term, but managers should be able to run a proactive plan by learning from the current crisis [19]. As there is no end in sight for the COVID-19 pandemic or whether another crisis is going to happen, managers need to think about re-organization for managing the risk in the pre-crisis period [30].

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

As is the case with any study, this study has certain limitations. Our findings are based on semi-structured interviews with only 12 stakeholders, which limits the generalization of the findings. However, given the limited time to complete the study, it was not possible to conduct more interviews. Therefore, in future studies, we will aim to conduct more interviews with a broader range of stakeholders to strengthen the findings. Future studies can also survey affected tourist businesses, as this will improve the generalizability of the findings. Integrating the qualitative inquiry with a quantitative approach would contribute to a better understanding of crisis management. Additionally, organization theory should be synthesized in further study in order to shed more light on how businesses can proactively rethink the crisis. The current study only utilized data from Thailand and, hence, in the future, more countries in which tourism is a key sector should be included to provide a more complete picture of the impact of COVID-19 and the recovery strategies of tourist businesses. In order to generalize the findings, the future study can also adopt a survey-based approach to collect data from a wide range of stakeholders. Finally, it would also be interesting to look at the impact of COVID-19 on businesses in other sectors. The findings from businesses in other sectors can also be useful in effectively dealing with uncertainty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and V.K.; methodology, S.P. and P.P.; analysis, S.P. and V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., P.P., V.K., and B.M.; visualization, S.P.; project administration, P.P.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Center of Excellence for Tourism Business Management and Creative Economy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Walailak University (WUEC-20-119-01 and date of approval 13 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Walailak University for supporting the grant for the Center of Excellence and also the funding of this project. We also wish to thank all the informants for their valuable data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L. An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Tourism. Thailand Tourism Statistics 2019. Available online: https://tourism.go.th (accessed on 10 April 2020).

- Hiemstra, S.; Wong, K.K.F. Factors affecting demand for tourism in Hong Kong. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 13, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.Y.F.; McCahon, C.; Miller, J. Modeling tourist flows to Indonesia and Malaysia. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 13, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soemodinoto, A.; Wong, P.P.; Saleh, M. Effect of prolonged political unrest on tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, R.; McKercher, B. The impacts of SARS on Hong Kong’s tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2004, 16, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Case study: Managing a health-related crisis: SARS in Singapore. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 10, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Chun, H.; Lee, H. The effects of SARS on the Korean hotel industry and measures to overcome the crisis: A case study of six Korean five-star hotels. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 10, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, N. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean, and Options for a Sustainable and Resilient Recovery; International Trade Series, No. 157 (LC/TS.2020/147); Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC): Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, O.; Landgraf, P.; Ind, N.; Markovic, S.; Koporcic, N. Corporate brand identity co-creation in business-to-business contexts. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 85, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.S.; Kingshott, R.P.J.; Sharma, P. Managing customer relationships in emerging markets: Focal roles of relationship comfort and relationship proneness. J. Serv. Theory Prac. 2019, 29, 592–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xue, T.; Wang, T.; Wu, B. The Mechanism of tourism risk perception in severe epidemic—The antecedent effect of place image depicted in anti-epidemic music videos and the moderating effect of visiting history. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, M.S. Protecting from brand burn during times of crisis, Mumbai 26/11: A case of the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower hotel. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 1309–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegner, S.M.; Beldad, A.D.; Kamphuis op Heghuis, S. How Company Responses and Trusting Relationships Protect Brand Equity in Times of Crises. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wei, H. How to save brand after crises? A literature review on brand crisis management. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 6, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkheimer, J.; Heide, M. Trust and brand recovery campaigns in crisis: Findus Nordic and the Horsemeat Scandal. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 2015, 9, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toanoglou, M.; Chemli, S.; Valeri, M. The organization impact of Covid-19 crisis on travel perceived risk across four continents. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pforr, C.; Hosie, P.J. Crisis management in tourism: Preparing for recovery. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 249–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, C. ‘This Is a Crisis.’ Airlines Face $113 Billion Hit from the Coronavirus. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/05/business/airlines-coronavirus-iata-travel/index.html (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Jamal, T.; Budke, C. Tourism in a world with pandemics: Local-global responsibility and action. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 6, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M. COVID-19 impacts and recovery strategies: The case of the hospitality industry in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S. Crisis Management; American Management Association: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, V. Flood management: Bradford paper. Disaster Prev. Manag. 1994, 3, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B. Towards a framework for disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosie, P.; Smith, C. Preparing for crisis: Online security management education. Res. Pract. HRM 2004, 12, 90–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, C.K.; Ding, C.G.; Lee, H.Y. Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahash, H.; Kulatanga, U. Understanding the terminologies: Disaster, crisis and emergency. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM conference, Manchester, UK, 5–7 September 2016; pp. 1191–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Radic, A.; Law, R.; Lück, M.; Kang, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.M.; Han, H. Apocalypse now or overreaction to coronavirus: The global cruise tourism industry crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, N.G.; Elphick, S. Models of crisis management: An evaluation of their value for strategic planning in the international travel industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 7, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.; Prideaux, B. Crisis management: A suggested typology. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, A.C.B.; So, S.; Sin, L. Crisis management and recovery: How restaurants in Hong Kong responded to SARS. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Krieger, J. Tourism crisis management: Can the Extended Parallel Process Model be used to understand crisis responses in the cruise industry? Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzie, A.; Kim, J.N.; Dell’Oro, C. Strategic value of employee relationships and communicative actions: Overcoming corporate crisis with quality internal communication. Int. J. Strat. Commun. 2012, 6, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, G. Internal communication—Essential component of crisis communication. J. Media Res. 2011, 10, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chemli, S.; Toanoglu, M.; Valeri, M. The impact of COVID-19 media coverage on tourist’s awareness for future travelling. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Building a barrier-to-imitation strategy model in the travel agency industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukic, B.; Meller, M. Creating information infrastructure in tourism industry cluster development. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference: An Enterprise Odyssey: Tourism—Governance and Entrepreneurship, Cavtat, Croatia, 11–14 June 2008; pp. 815–826. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. Building up a B2B e-commerce strategic alliance model under an uncertain environment for Taiwan’s travel agencies. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1308–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chang, W.; Chen, C.W. Do switching barriers exist in the online travelling agency? J. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Su, C.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, G. Contract design capability as a trust enabler in the pre-formation phase of interfirm relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzunkan, D. Customer relationship management in business-to-business marketing: Example of tourism sector. Geoj. Tour. Geosites. 2018, 22, 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K. Marketing Management, Analysis, Planning, and Control; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, S. Consumers and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.B. How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J.E. The cultural codes of branding. Mark. Theory 2009, 9, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.; Kaufmann, P.J. Channel members’ relationships with the brands they sell and the organizations that own them. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 83, 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Wang, W.Y. The corporate brand and strategic direction: Senior business school managers’ cognitions of corporate brand building and management. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, G.; Yu, L.; Armoo, A.K. Crisis management and recovery. How Washington, D.C. Hotels responded to terrorism. Cornell Hotel Restau. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, J. Crisis management in international business: Keys to effective decision making. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1994, 15, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.T. Knowledge management adoption in times of crisis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Hyun, S.S. The effects of perceived destination ability and destination brand love on tourists’ loyalty to post-disaster tourism destinations: The case of korean tourists to Japan. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Sarkar, J.G.; Sarkar, A.; Eshghi, A.; Anusree, M.R. The impact of other customer perception on consumer-brand relationships. J. Serv. Theory Prac. 2018, 28, 130–146. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.J.; Ryu, H.B. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), traveler behaviors, and international tourism businesses: Impact of the corporate social responsibility (CSR), knowledge, psychological distress, attitude, and ascribed responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amujo, O.C.; Otubanjo, O. Leveraging rebranding of “Unattractive” nation brands to stimulate post-disaster tourism. Tour. Stud. 2012, 12, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Sung, Y.H.; Kim, D.H. Brand personality usage in crisis communication in Facebook. J. Promt. Manag. 2017, 24, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.J. Interpreting consumers: A hermeneutical framework for deriving marketing insights from the texts of consumers’ consumption stories. J. Consum. Res. 1997, 34, 438–455. [Google Scholar]

- Young, E. How The Pandemic Will End? The Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2020/03/how-will-coronavirus-end/608719/ (accessed on 28 April 2020).

- Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate brand orientation: What is it? What of it? J. Brand Manag. 2013, 20, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M.J.; Schultz, M. Bringing the corporation into corporate branding. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 37, 1041–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Kok, S.K.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Sakellarios, N.; Koresis, A.; Buitrago Solis, M.A.; Santoni, L.J. COVID-19, aftermath, impacts, and hospitality firms: An international perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, J.L. Reflecting on the tensions between emic and etic perspectives in life history research: Lessons learned. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2014, 15, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, Q.; Chon, K. COVID-19 and China’s hotel industry: Impacts, a disaster management framework, and post-pandemic agenda. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedeliento, G.; Andreini, D.; Bergamaschi, M.; Klobas, J.E. Trust, information asymmetry and professional service online referral agents. J. Serv. Theory Prac. 2017, 27, 1081–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Koporcic, N.; Halinen, A. Interactive network branding: Creating corporate identity and reputation through interpersonal interaction. IMP J. 2018, 12, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, J.M. Tourism business responses to South Africa’s COVID-19 Pandamic Emergency. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 35, 338–347. [Google Scholar]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N. Tourists’ and tourism suppliers’ perceptions toward crisis management on Tsunami. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urde, M. Core value-based corporate brand building. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1017–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).