1. Introduction

Academicians have investigated the relationship between human resource management systems and organizational performance for over two decades now [

1]. Talent mobility in the 21st century has reached unprecedented levels, as the workforce seeks constant gratification of their individual demands [

2]. Therefore, retaining an employee that is not only skilled, but also maintains a work–life balance along with a perceived fit between self and organization, has become increasingly essential [

2]. The current century is an era marked by greater levels of employee mobility, as they constantly seek higher gratification of their own objectives, hence making it imperative for the organization to strive harder to retain them not only as satisfied employees, but also as having a greater affective organizational commitment [

2]. For the same reason, organizations continually strive to foster an encouraging climate to help employees maintain a work–life balance by providing positive work conditions and to endow adequate training to attain person–job fit [

3].

The current study responds to the research by Mahmood et al. in 2019, which called for further investigating the area in the context of Eastern cultures and developing countries [

1]. Therefore, in this study, the relationship of work–life balance, person–job fit, and work conditions is investigated in reference to affective organizational commitment. Furthermore, the mediating role of job satisfaction is also studied. These constructs are an essential part of human resource management systems, which are carefully designed to enhance employee participation and performance [

4,

5]. Higher levels of employee morale and performance ensured by human resource management will result in enhanced job satisfaction and greater affective organizational commitment, thereby achieving the ultimate purpose of a sustainable competitive advantage for the company [

6,

7]. This study attempts to build on previous research and provide a larger view of the phenomenon within the private sector from the emerging economy perspective.

Pakistan is among the emerging economies, and with the rising standards of development, the environment at the workplaces has increased in competition. Firms now require optimally qualified and highly skilled employees, as this determines the quality of organizational output and productivity [

8]. On the other hand, these employees look for workplaces that offer them good work conditions, attractive remuneration, work–life balance, and person–job fit [

9]. Retaining skilled employees has mostly been a dilemma for HR practitioners [

10]. Furthermore, in the private sector, as appraisals are performance-based, dissimilarities subsist regarding salary structures, fringe benefits, work conditions, and recognition, which leads to changes in job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment [

11]. These disparities are mainly due to the differences in the industry, the HR policies of the company, and the qualifications/skills of the employees [

12]. The market setup of Pakistan is still unstructured, and therefore, private companies, both local and multinational, have to face innumerous impediments with issues such as job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment, resulting in rising frustration amongst employees [

1].

The current study provides a fresh perspective in the field of HR and organizational behavior. Previous research conducted by Fabi et al. (2015) in Canada and another work conducted in Spain by Luna-Arocas and Camps (2008) tested the relationship between job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment, with a high power work system (HPWS) as antecedents [

7,

13]. The current study extends their work and investigates the influence of person–job fit, work conditions, and work–life balance as the antecedents for job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment.

There is a dominance of the U.S. paradigm in management research that generally endorses context-free knowledge [

14]. They encourage Western-trained researchers to conduct HRM research in non-Western countries to address this imbalance. Brewster (2007) contends that a set of HR practices will work differently in dissimilar social settings because of contingency-oriented approaches [

15]. Lane and Wood (2009) state that work practices differ at national and sectoral levels [

16]. It has been argued that some Western high-performance work practices might not be affective in an Asian country context [

17]. It is, therefore, important to understand the HRM systems within a certain management and national culture context [

18].

According to Warsi et al. (2009), HR practices and strategies are still inadequately evident and insufficiently theorized in South Asia [

12]. This study provided a basis to extend the discussion in the same region and presented an emerging economy perspective. Some research in the wider context of Asia has been found, which provides evidence that human resource practices cause variation in the way employees perceive, which further influences their behavior and attitudes [

19,

20,

21]. Studies conducted in the neighboring country of India confirmed that striving for greater employee commitment leads to beneficial results in terms of organizational productivity [

22,

23].

Although significant research about the human resource practices and affective organizational commitment has been done in the past, according to Mahmood et al. (2019), there is a dearth of studies in South Asia in general, and very few studies have been conducted on Pakistan and none specifically on the entire private sector, to the best of our knowledge [

1]. Some investigations carried out in the region have focused on specific industries only, which include a study by Azeem and Akhtar (2014), who investigated the Indian health care sector [

24]. Furthermore, a study was conducted by Farzaneh et al. (2014) on Gas Transfer Company in Iran, while Akter et al. (2019) investigated university teachers in Bangladesh [

25,

26]. In Pakistan, Jawaad et al. (2019) explored the telecom sector, and Mahmood et al. (2019) presented a comparison between private and public sector banking employees [

1,

27].

Among academicians, little has been identified about the implications of the hypothesized relationships of work–life balance, person–job fit, and working condition with affective organizational commitment via the intervening character of job satisfaction. Lok and Crawford (2004) investigated the influence of education, age, and experience on affective organizational commitment in Australian and Chinese samples and suggested that these relationships should be further probed in other societies with varied managerial practices, philosophies, and organizational cultures [

28]. Moreover, Straatmann et al. (2020), in a fairly recent study, called for investigating affective organizational commitment for employees relevant to both the duration of employment in the organization and total experience in the industry [

29].

The conceptual framework of the current study is comprised of constructs that have never been investigated holistically in a single study for private or public sector employees in developing or developed countries, to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, the current study adds to the existing literature in the area, as it provides a unique perspective of optimizing the affective organizational commitment in the assessment of work–life balance, person–job fit, working condition, and mediation of job satisfaction in the inadequately investigated and evolving context of various private sector industries of Pakistan.

In summary, this study makes a contribution to the existing literature in five aspects. First, it introduces the constructs of person–job fit and work–life balance, along with work conditions as antecedents to job satisfaction, as there are hardly any studies that have examined these antecedents in a collective manner. Second, it provides empirical evidence for the conceptually proposed, but hardly tested relationship between person–job fit and affective organization commitment using social exchange theory. Third, it strengthens the conjectural underpinnings of the proposed relationships using multiple theories, social exchange theory (SET) and conservation of resources (COR) theory. Fourth, it uses a large sample size across multiple industries to improve the generalizability of the findings. Fifth, it uses an emerging market context to test the validity of the theoretical concepts mainly originating from developed countries with a different contextual environment.

1.1. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

1.1.1. Underpinning Theory

The current research study is grounded in social exchange theory and conservation of resources (COR) theory [

30,

31]. It explains how and why employers strive to aid employees in the maintenance of work–life balance, provide conducive work conditions, and facilitate person–job fit, which will contribute towards higher job satisfaction and eventually higher affective organizational commitment. According to COR theory, an individual strives to acquire and retain valuable resources such as self-esteem and time, while the loss of these resources results in great psychological distress. When the demands at the workplace increase, it results in greater spending of the resource such as time and energy, which are limited, and hence less of them are available to be spent with the family [

32,

33].

Social exchange theory proposes that employees are optimally satisfied and offer a higher commitment to the organization if the latter provides them with support and care for their family life [

34,

35,

36].

1.1.2. Work–Life Balance and Affective Organizational Commitment

In recent years, significant attention has been given to the construct of work–life balance (WLB); however, it is evident that minimal focus was given to exploring the concept with regard to private sector employees [

37,

38,

39]. Compared with the public sector, the private sector faces an increased demand for new products, intense competition, need for technological advancements, extended working hours, and hectic schedules, particularly in a South Asian context, which makes it imperative to investigate work–life balance among private-sector employees [

40]. According to Greenhaus et al. (2003), work–life balance refers to a balanced fulfillment between both personal responsibilities and occupational roles [

41]. It basically refers to having steadiness and stability amongst the professional responsibilities and personal engagements that are critical to individuals, like community roles, the activity of leisure, and family responsibilities. For most employees working in various industries from the private sector, striking this balance has largely been a challenge [

42]. When an individual stays occupied with work-related roles, there will be a higher probability that work–life balance will be disturbed, resulting in increased job dissatisfaction and reduced commitment, leading to psychological stress [

43]. Employees normally strive for adaptable arrangements at work so that they have sufficient time for recuperating from work stress and for family life [

44,

45]. Therefore, employees who have prospects of working in a flexible routine are able to preserve work–life balance, and they reciprocate with stronger commitment towards the organization, and this argument endorses the social exchange theory [

36,

46]. The work–life balance considers the perceived fair treatment and the position it has in the social exchange process [

47].

Organizations should put in effort to aid the employees towards integrating their family and work life [

48]. A higher level of job satisfaction increases the probability of the employee feeling more attached to the organization, which consequently increases their level of affective organizational commitment [

49].

In light of the above literature, the following relationship was hypothesized:

H1a. Work–life balance has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

1.1.3. Person–Job Fit and Affective Organizational Commitment

The literature has theoretically explained the relationship of person–job fit and affective organizational commitment with the help of social exchange theory (SET), but empirical testing has largely been scarce [

29,

30]. Person–job fit (PJ fit) is defined as “the match between an individual and the requirements of a specific job” [

50]. PJ fit specifically refers to the extent to which the qualifications, skills, knowledge, and abilities of an individual are in line with the requirements of the job [

51]. The underlying principle with regards to PJ fit is that employees’ personal endeavors and experiences give form to their own version of reality, including cognitions and emotions, which contribute to job satisfaction and eventually affective organizational commitment [

25,

52]. Organizations strive to recruit and select such individuals, while academicians have demonstrated a relationship between PJ fit and affective organizational commitment [

53]. The achievement of a work objective and a successful work behavior establishes faith in the employee and develops a degree of confidence about their acumen, which are the basics of the concept of social cognitive theory [

54,

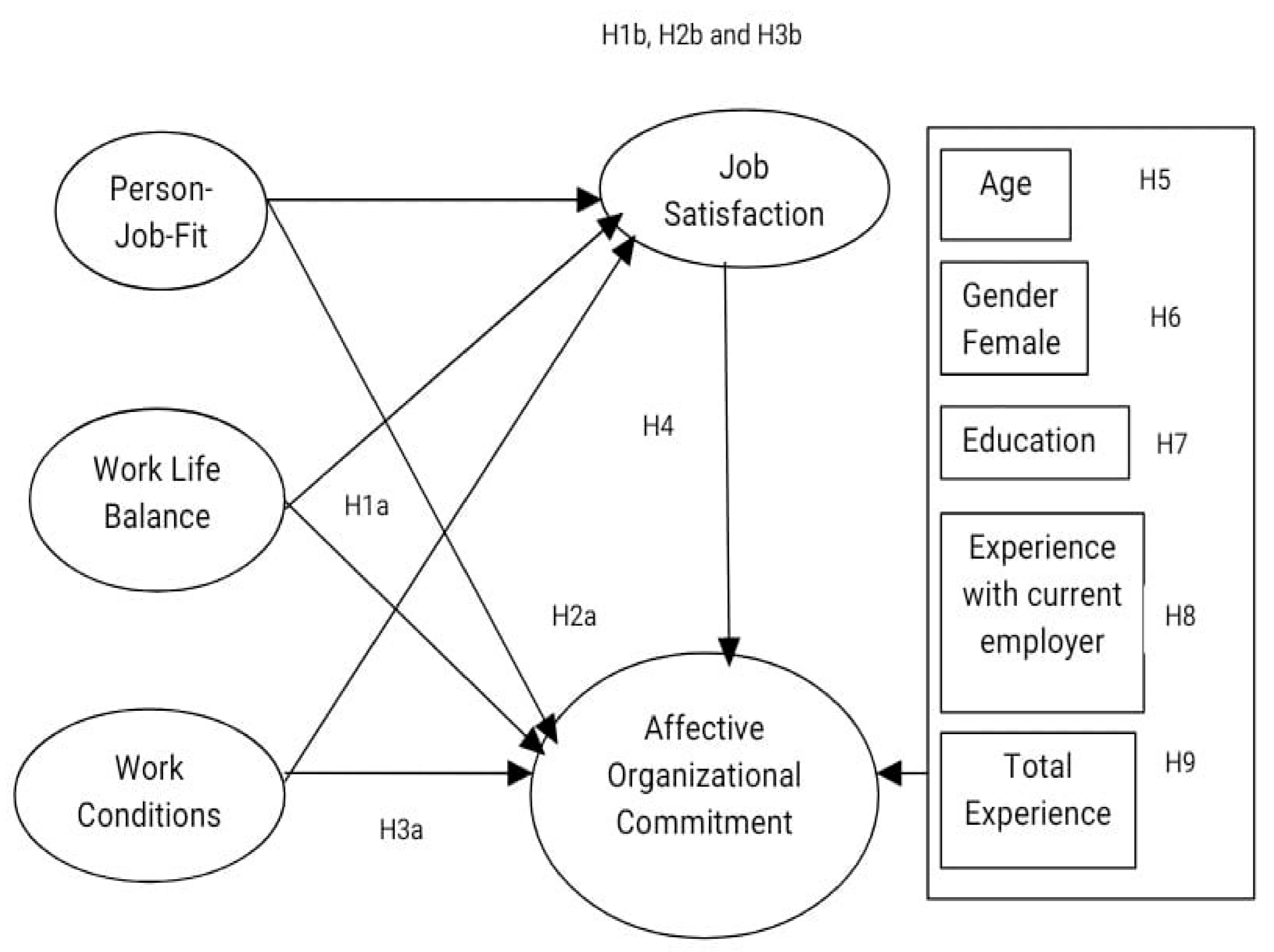

55]. This confidence is integral in optimizing levels of motivation and, consequently, the perception of PJ fit for the employee. Kristof-Brown et al. (2005) investigated and concluded that PJ fit has a strong relationship with affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction (

Figure 1) [

53]. The literature confirms that the perception of this fit significantly contributes to individual performance [

56]. A meta-analysis conducted by Verquer et al. (2003) confirms that PJ fit has a significant relationship with job satisfaction and, consequently, with affective organizational commitment [

57].

Employees with a higher perceived PJ fit will attach a higher cost to switching organizations, which is the reason that they do not want to potentially miss out on the match between personal abilities and skills with job demands, and eventually the rewards of organizational membership [

58]. The opinion about the similarity of personal and organizational values may lead to the perception of increased social demand and importance to conform to organizational values, which leads to amplified affective organizational commitment [

59].

In light of the above literature, the following relationship was hypothesized:

H2a. Person–job fit has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

1.1.4. Work Conditions and Affective Organizational Commitment

Work conditions have a significant role to play in determining employee engagement, and the literature supports the notion that absenteeism and employee complaints substantially reduce the presence of good work conditions, at the same time decreasing productivity and eventually commitment [

60].

Work conditions include the characteristics of the job and workplace structural factors in relation to job satisfaction [

61,

62]. Significant evidence from the available literature suggests that work conditions influence job satisfaction, as well as the physical and mental well-being of the employee [

63,

64]. Several studies have revealed that unpleasant work conditions have an effect on the emotional well-being of the employee [

65]. Poor work conditions result in employee burnout, and consequently puts emotional stress on them [

66]. Conducive work conditions can aid the organization in reducing absenteeism, alleviating grievances at work, elevating job satisfaction, and eventually increasing the affective organizational commitment [

67]. Poor work conditions are critical in lowering job satisfaction and performance, while contributing towards a high turnover [

63].

Rapid changes and growth in technology require both the development and refinement of skills in the employees, for which the employers strive to provide training and better work conditions, but previous research concludes that such opportunities of skill development and training are not given out equitably [

46,

68,

69,

70,

71]. Alvesson (2000) expressed the relevance of work conditions in the light of social exchange theory, and explained that increased commitment is due to the understanding of fairness and mutuality [

72]. The employee reciprocates fair treatment and favorable work conditions with increased affective organizational commitment [

47].

Private sector companies are continuously striving to maintain greater levels of customer satisfaction, as it is integral to maintain a competitive advantage. Organizations must have good knowledge about maintaining a diverse workforce, which aids in processes from recruitment to the retention of committed employees and guarantee amplified levels of job satisfaction [

73].

In light of the above literature, the following relationship was hypothesized:

H3a. Work condition has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

1.1.5. Job Satisfaction and Affective Organizational Commitment

Organizations strive to deal with increasing diversity among employees, which requires them to manage the processes of recruitment, challenges of retention, and eventually ensuring high levels of job satisfaction [

74]. According to Heathfield (2019), in order to maintain high levels of job satisfaction, it is pertinent to comprehend the elements that lead to it [

73]. The influence of human resource management practices on affective organizational commitment has been investigated well in the existing literature, but scarce attention has been given to the psychological aspect that underlies the relationship between these practices and affective organizational commitment [

75]. According to social exchange theory, the employers focus on the need fulfillment of the employees, who reciprocate with favorable behavior such as job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment [

29]. The exchange between employees and employers is a relationship based on trust and commitment, whereas any discrepancy may end the relationship [

76,

77,

78]. Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

H4. Job satisfaction has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

1.1.6. Affective Organizational Commitment

The existing literature explains the concept of commitment as a pivotal cognitive process of relating with ones’ organization [

84,

85]. Affective organizational commitment of the employee is identified as a psychological attitude that allows the employee to recognize the objectives and ideals of the organization [

86]. O’Reilly and Chatman (1986) defined affective organizational commitment as an employee’s psychological attachment with the organization, or a bond between employee and the organization [

58,

87]. This bond reduces any chance of “voluntary turnover” [

83]. The literature has acknowledged multiple aspects of this psychological bond with the organization [

29]. The relationship between the PJ fit, WLB, work conditions, and affective organizational commitment is rooted in social exchange theory [

29]. According to Allen and Meyer (1996), affective commitment is represented by the emotional attachment and involvement that an employee feels with the organization [

88]. As a result of this, employees experience a sense of motivation to enliven the organization’s value system and remain dedicated to the employer [

89]. For organizations, employee commitment is of great value, as it leads to a higher job performance, consequently establishing and maintaining a stronger competitive advantage for the company [

90].

Employees perceive organizations as an entity that fosters a balance in their work and family life, provides favorable work conditions, and strives to train or develop them to experience a fit between themselves and the organization. As a result, the employee develops a sense of obligation to stay committed to the organization [

48,

91].

Studies have also identified that affective organizational commitment leads to job satisfaction, while in connection to high-performance work structures; the literature dated to the previous decade suggests a path from affective organizational commitment to job satisfaction [

86,

92]. In a similar investigation conducted in China, Fu and Deshpande (2014) claimed that a sympathetic atmosphere considerably influenced affective organizational commitment through the intervention of job satisfaction [

93]. Another investigation by Fabi et al. (2015) concluded that levels of job satisfaction drastically influence affective commitment, thereby significantly lowering any intention to leave the organization [

13]. Although previous studies have shown job satisfaction as both an antecedent [

13] and as a consequence of organizational commitment [

81,

87,

94], in the current study, we are investigating job satisfaction as an antecedent of organizational commitment.

According to Lok and Crawford (2004), there is a positive relationship between tenure, educational level, age, and the duration of leadership with affective organizational commitment in East Asian organizations [

23]. Mathieu and Zajac (1990), and Chen and Francesco (2000) suggested that variables such as education, age, and leadership duration can have a critical influence on employees’ affective organizational commitment [

58,

95]. Another Korean study conducted by Sommer et al. (1996) concluded that age, position, and tenure have a significant relationship with affective organizational commitment amongst Korean respondents [

96]. Employees who have spent a long time in a certain organization and have risen to higher levels have greater levels of affective organizational commitment [

28]. The studies conducted recently on Western subjects showed consistent results. Sommer et al. (1996) concluded that there was a difference in the relationship between education and affective organizational commitment between earlier findings in Western subjects and Korean subjects, mainly due to contrasting cultures [

96]. Looking through the lens of Confucian philosophy, factors such as respect of elders, leadership, education, loyalty, and conformity are diverse between Eastern and Western societies [

97,

98,

99,

100]. According to Hofstede (2011), women, on average, in most countries, are more likely to choose good work conditions and job security more than men [

101]. Comparable differences among gender were also concluded for GLOBE’s human orientation measure, which has stressed the social and cultural goals [

102]. Based on this literature, it is anticipated that demographic variables, including gender, have a relationship with affective organizational commitment, which should be investigated.

The current study adds to the existing literature and focuses on emerging economies such as Pakistan in its investigation of the relationships between demographic variables and affective organizational commitment.

H5. Age has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

H6. Female gender has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

H7. Education has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

H8 Experience with a current employer has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

H9. Total experience has a significantly positive relationship with affective organizational commitment.

4. Discussion

Affective organizational commitment and the underlying psychological phenomenon have been of great interest for academicians and practitioners [

53,

114]. Although the influence of the human resource practices on employee attitudes and behaviors has been under a significant spotlight, the current study, being the first of its kind, adds to the existing literature by unraveling the influence of work–life balance, person–job fit, and work conditions on the affective organizational commitment of employees working in the private sector in an emerging economy such as Pakistan [

53].

A distinctive contribution of the current study is the application of social exchange theory (SET) and conservation of resources (COR) theory in order to offer a better understanding concerning the psychological mechanism of these relationships [

30,

31]. Although both SET and COR have been investigated to be central tenets in explaining the employee–organization relationship, the development of these concepts has largely been done separately [

115,

116]. In particular, the investigation of the relationships mentioned above, through the lens of SET and COR, has not yet been the focus in a single study from an emerging economy perspective. Job satisfaction reflects the need for gratification from an SET perspective, while work–life balance and work conditions are strongly linked to COR theory. The current study was structured to incorporate the two theoretical notions in explaining the influence of work–life balance, person–job fit, and work condition on affective organizational commitment, along with the intervening character of job satisfaction.

In line with HR typology presented by Wright and Boswell (2002), the unit of analysis was an individual employee in a South Eastern context, while our sample size was much larger in comparison with Mahmood et al. (2019), Luna-Arocas and Camps (2008), and Fabi et al. (2015) [

1,

7,

13,

117]. In order to respond to the call of research made by these researchers, this study collected a large sample from private-sector employees in order to provide a greater comprehension of the underlying variables in an emerging economy and South East Asian cultural perspective such as Pakistan. The current study is an attempt to exploit the enlightening influence of said theories, so that a better comprehension and effectiveness of the theoretical model can be presented.

With regards to the hypothesis for direct relationships (latent variables), we see that work–life balance leads to stronger affective organizational commitment. In the private sector, employees seek to work in organizations that provide them with adaptable arrangements at work, so that the employee is able to establish and maintain a balanced work and family life. As a result, the employee reciprocates with augmented affective organizational commitment. These results are consistent with Herrbach et al. (2009) [

46]. The results also confirm that job satisfaction behaves as a link between work–life balance and affective organizational commitment, but there is a possibility of an omitted variable as the mediation is complimentary. With regards to person–job fit, we find that it leads to amplified affective organizational commitment as well. When a private sector employee realizes that his skill set and aptitude match well with the organization, he values it tremendously and commits himself/herself even more strongly to the organization. Although the mediation is complementary, person–job fit also results in heightened job satisfaction, and consequently raises affective organizational commitment. When it comes to work conditions, we find that it does not influence affective organizational commitment, but the relationship between the two is only established in the presence of job satisfaction. Although work conditions in the private sector might be conducive for facilitating employees, they are not detrimental in the development of strong affective organizational commitment unless an employee is satisfied at the job. Therefore, full mediation is found in this case, and there is no omitted variable in the above-mentioned relationship of work condition. One of the probable reasons that Hypothesis 3a is not supported, is that the validated measures taken from the literature for work conditions might be more relevant to blue color jobs, while the respondents for this research are mainly white collar (managerial) employees who, in a high-power distance society like Pakistan, tend to encounter a better working environment. However, more research is needed to further examine this phenomenon.

One of the interesting findings from the research is the confirmation that stronger affective organizational commitment manifests from higher job satisfaction amongst private sector employees. Thus, for Pakistani private-sector employees, work–life balance and person–job fit significantly influence affective organizational commitment, but work condition increases affective organizational commitment through feelings of job satisfaction alone.

With reference to the influence of demographic variables, we find that as the age of the employee increases, the affective organizational commitment becomes stronger. The relationship of total experience and experience with the current employer is also significant in determining a stronger affective organizational commitment. These findings are consistent with Western culture and also with a study on Korean subjects, but interestingly, Chen and Francesco (2000) had contradictory findings among Chinese subjects [

28,

95,

96]. As an employee ages, their experience both in the industry and in the current organization increases; as a result, not only maturity and sensibility sets in, but the understanding of the organizational culture aids in the development of a comfort zone, thereby amplifying affective organizational commitment. The analysis revealed an interesting relationship between gender and education with affective organizational commitment among the sample. In contrast with the results of Western studies, no relationship of education with affective organizational commitment was found in the current study [

96]. A possible reason could be that in Pakistan, the education level and the institutional repute are strongly linked with the choice of occupation and organization. This leads to a clearer understanding of the rewards and remuneration. Hence, there are no unmet expectations, resulting in the absence of a significant relationship between the two.

Regarding the relationship of gender with affective organizational commitment, we found that females have a stronger affective organizational commitment than males. Pakistani society is characterized by higher societal concerns for femininity, which is linked with a high commitment by women. The strong affective organizational commitment of women is not due to eccentricity, but due to less tolerance for ambiguity and societal restraint orientation. Because of the underlying patriarchal nature of Pakistani society, women have to face significant hurdles in establishing the freedom needed to carry out a job in the private sector. Once they secure employment, they would most likely show a strong commitment. The findings are consistent with samples from Bulgaria and Romania [

118]. Despite the fact that more and more women have entered into the corporate workplaces, these findings also suggest that in Eastern societies, such as Pakistan, the primary responsibility of providing for the family, including elderly parents, wife, and children, is still heavily rested on the male members. Therefore, males are constantly striving to seek employment in organizations that offer better remunerations and rewards compared with the current employer. Therefore, males pivot on the skill development, training, and experience gained at the current organization and seek better positions and attached salary enhancement in another organization, which reflects a negative affective organizational commitment with the first.

The results from this study stress the importance of understanding the broad socio-historical perspective of an emerging economy such as Pakistan. The prevalent high levels of unemployment and poverty coupled with the abundance of labor account for stronger affective organizational commitment. Employees cling to strong unemployment concerns and are cognizant of their substitutability, and therefore, the results are in contrast to affluent nations and developed economies such as Spain, Canada, and those from Central and Eastern Europe [

7,

13,

118].

Human resource practices in private sector organizations are heavily influenced by prevalent cultural values. The current study confirms that cultural and societal norms have a strong influence on the way human resource practices shape the attitudes and levels of commitment amongst private-sector employees. Therefore, other than all endogenous variables of the study, we can say that the decision to leave any organization may be dependent on the economic, cultural, and social variables in private sector organizations in emerging economies such as Pakistan.