Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- the tourist experience—experiences in different destinations, make tourists more carefree in face of any potential risks [51,53,54,55]. People tend to protect themselves more when faced with unknown situations. These conclusions are similar to those found by Lepp and Gibson [53]. The authors indicated that tourists with tourism experience tend to perceive less the risks.

- (2)

2. Material and Methods

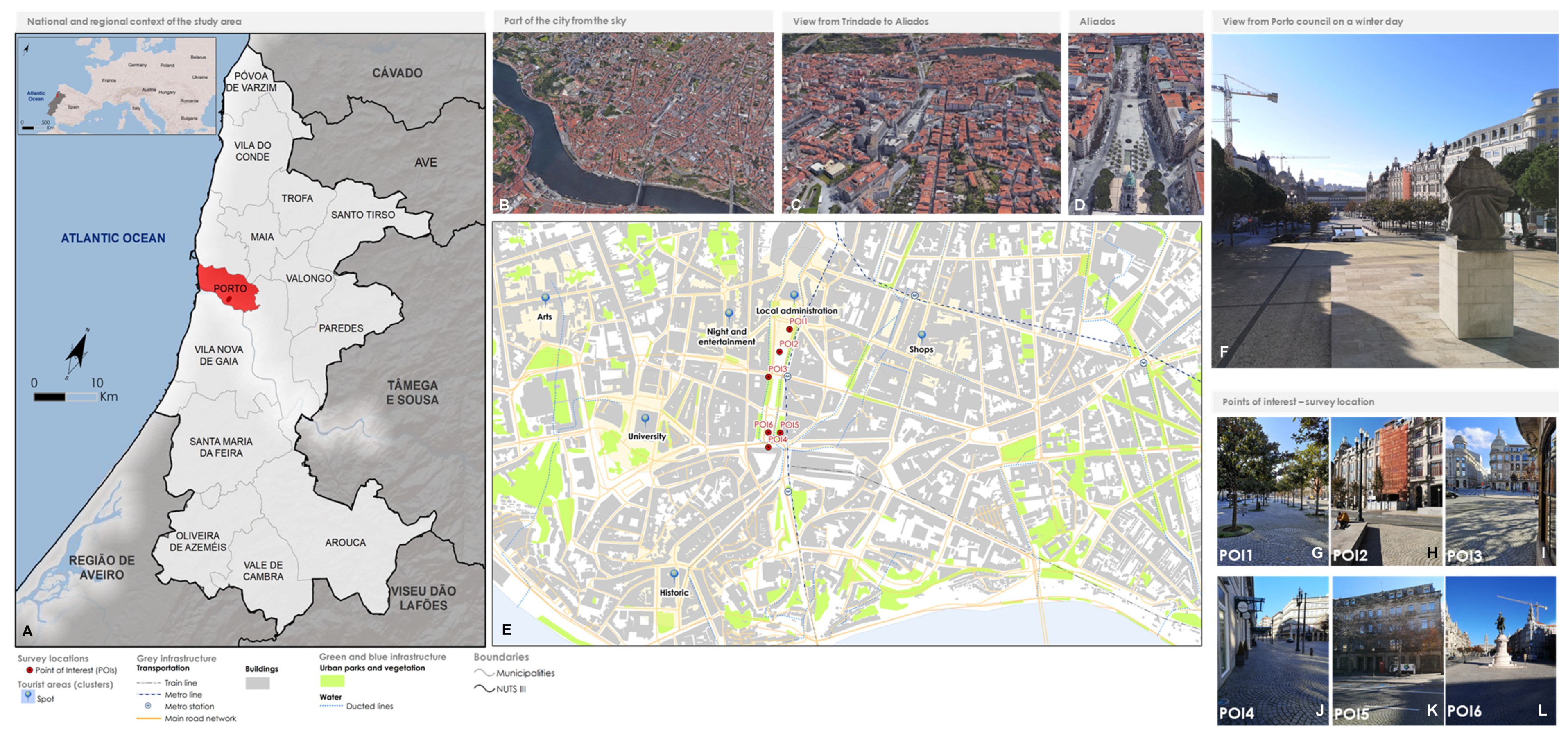

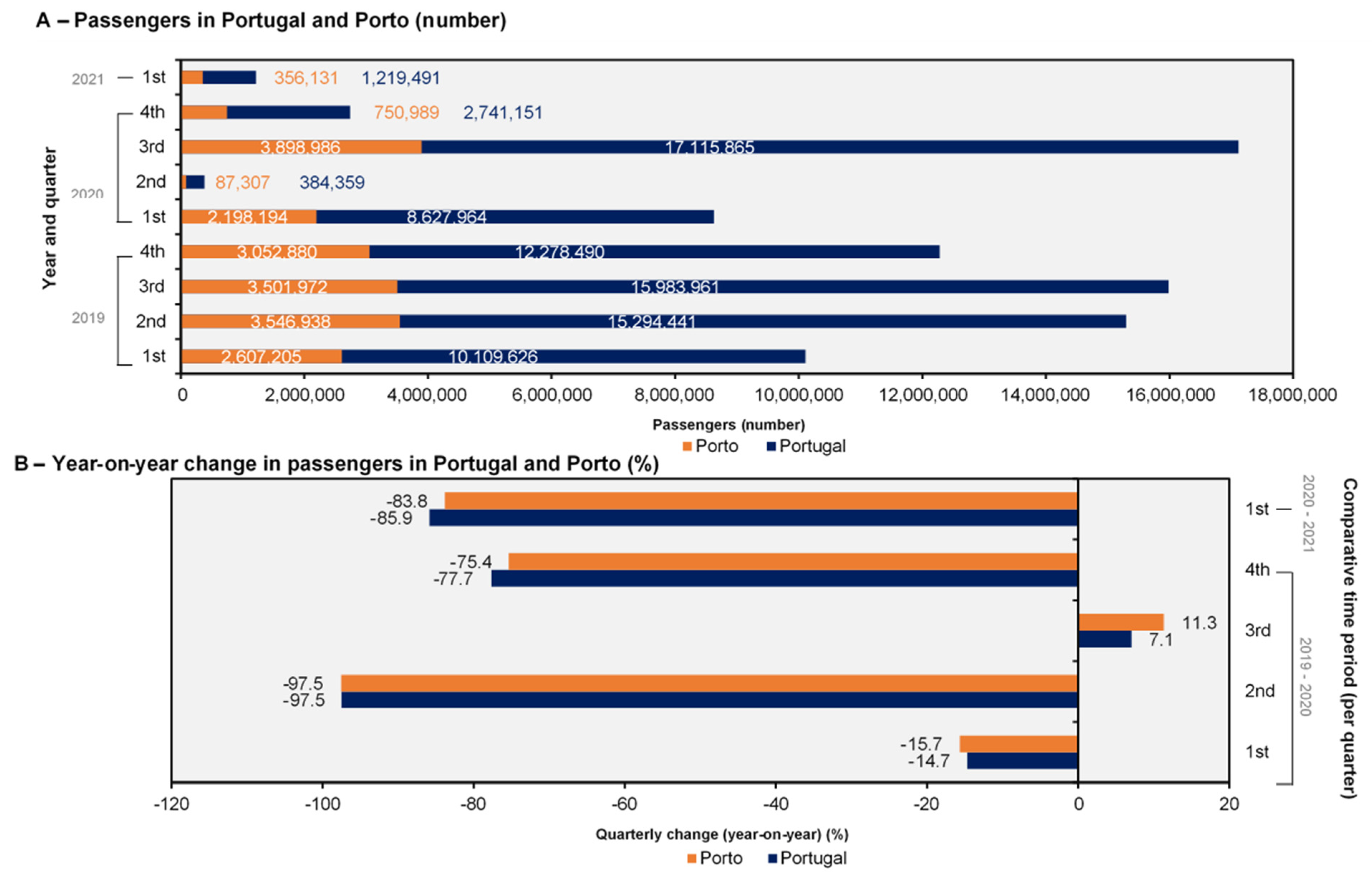

2.1. Study Area

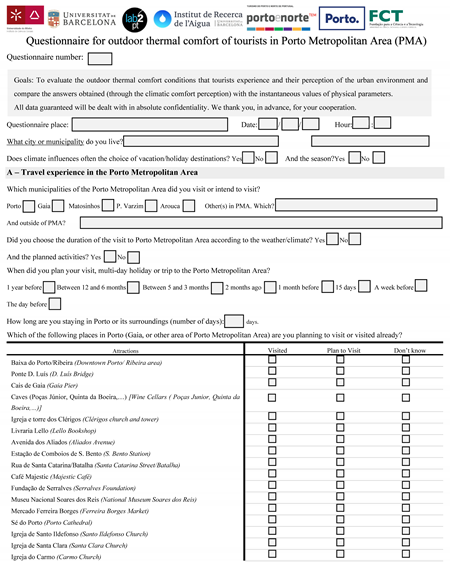

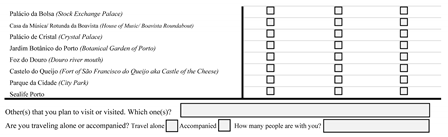

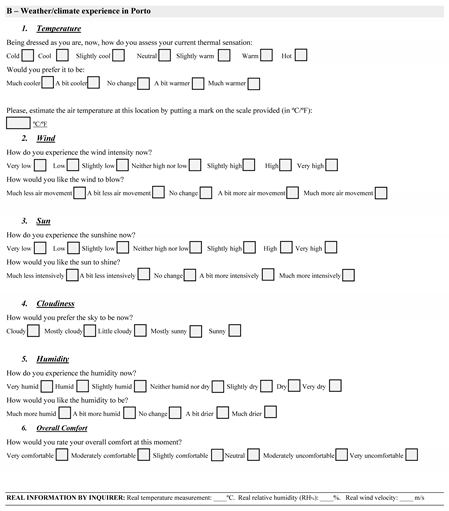

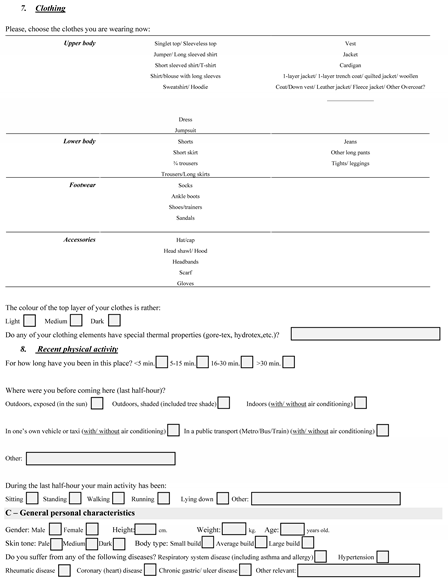

2.2. Questionnaire Design

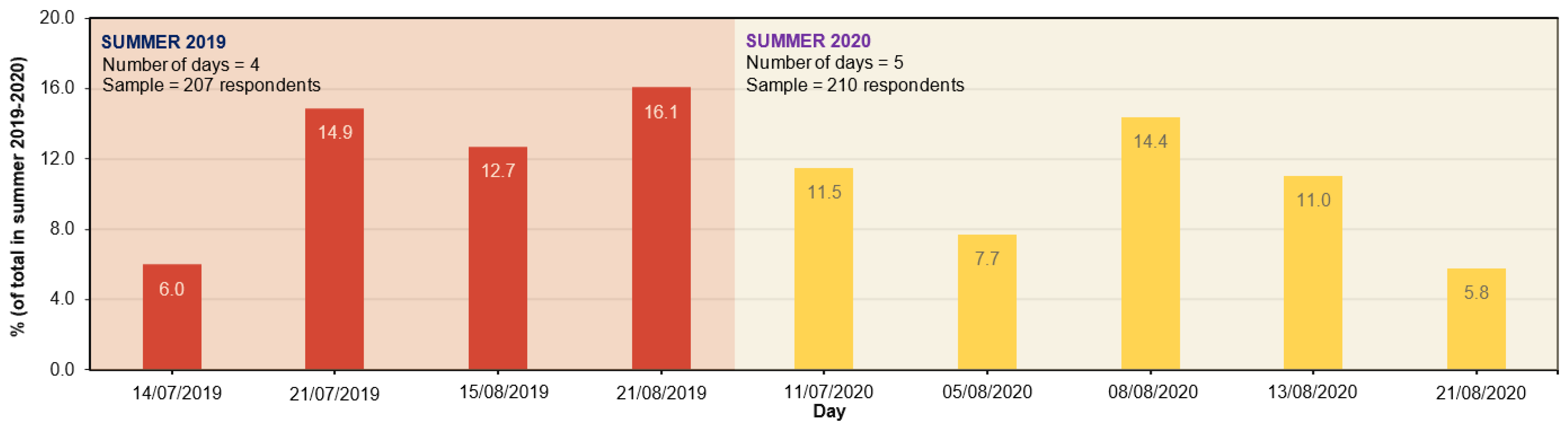

2.3. Sample

2.4. Survey Application

2.5. Data Analysis and Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Sample Demographics

- (1)

- many of the countries did not allow tourists to leave to visit Portugal, and when tourists did, they forced them into lockdown after returning to their country of origin;

- (2)

- there was a generalized perception of risk, which reduced the number of trips on a large scale and in large groups, in addition to the generalized reduction in tourist excursions in this period. In this regard, the number of tourists traveling alone decreased from 17.9% to 7.6%, whereas the number of tourists who traveled as a couple or with family (usually the closest family, including children) increased.

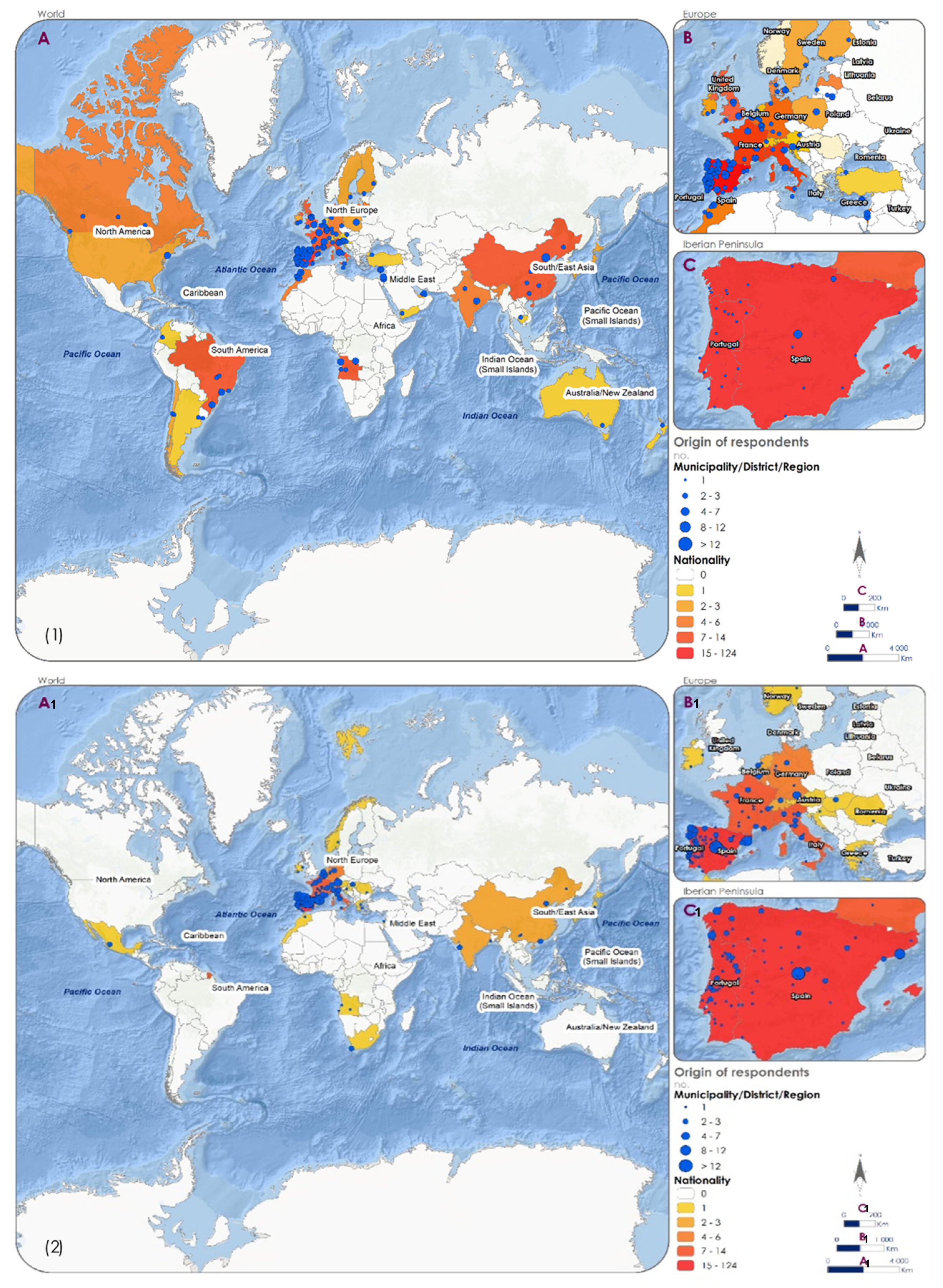

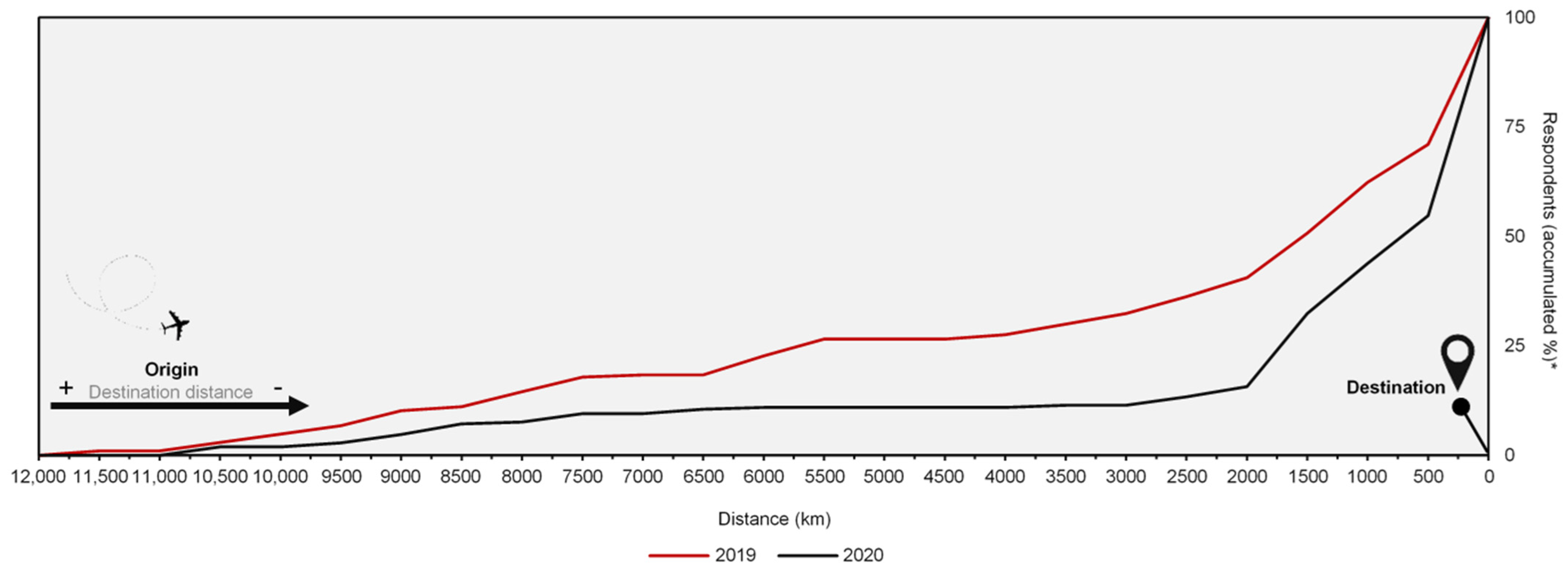

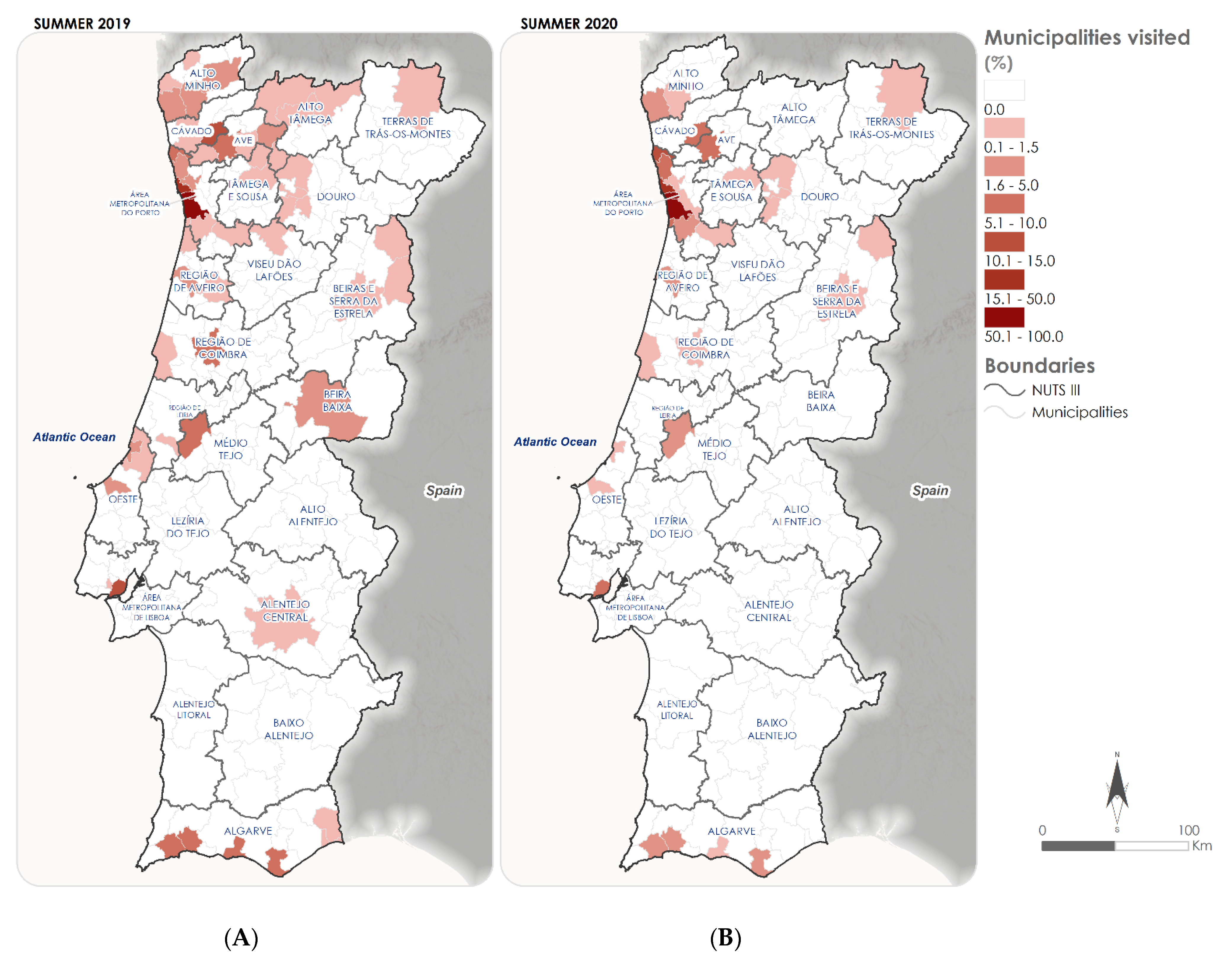

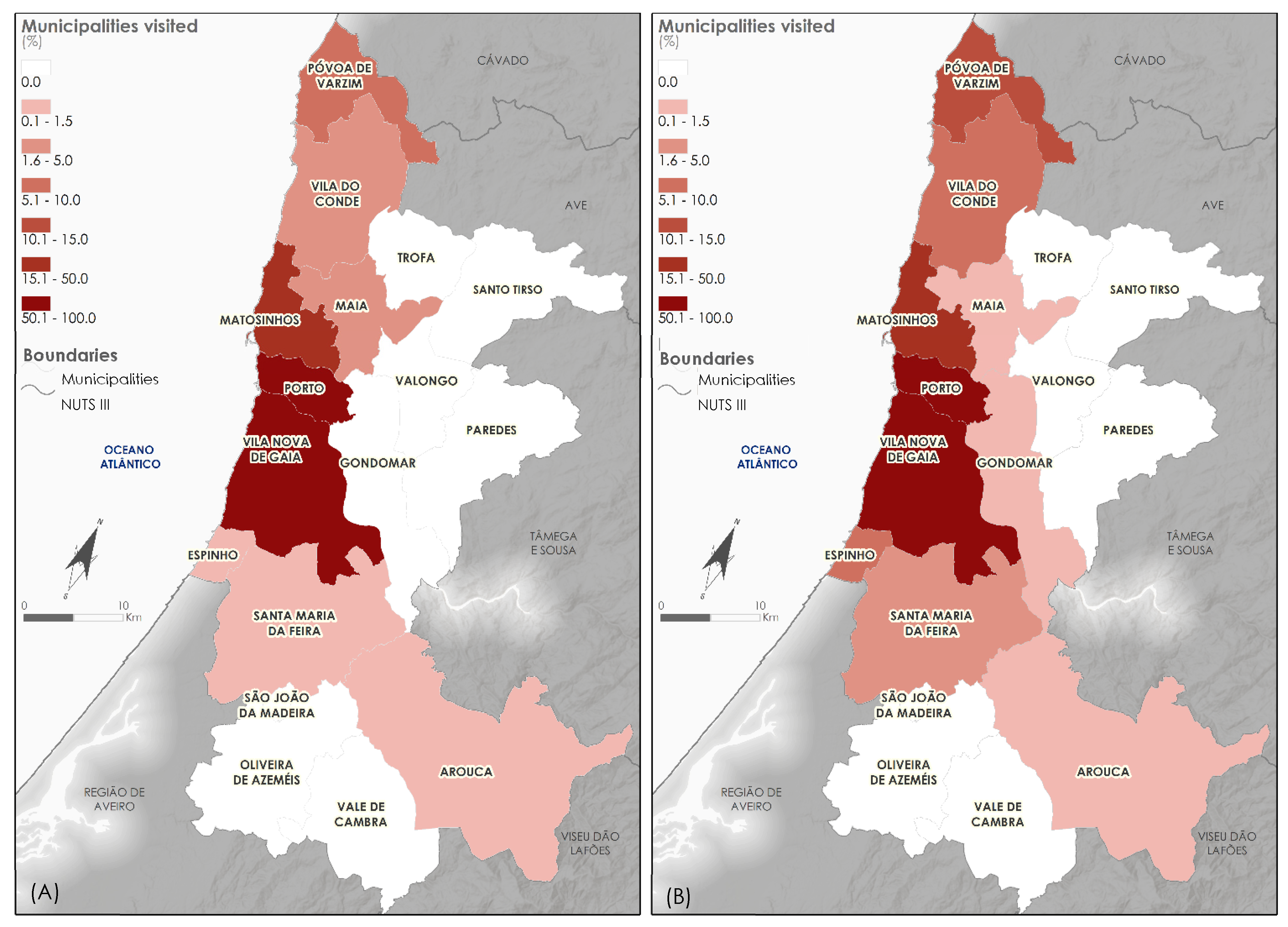

3.2. Geographic Context of Visitation—Tourist Origin and Places Visited in Porto

- (1)

- most tourists visited other large or medium-sized cities in addition to Porto (namely Greater Porto, Lisbon, and Algarve and some district capitals);

- (2)

- tourists took the opportunity to get to know the municipalities bordering Porto (around Porto).

- (i)

- the visit pattern associated to the major destinations in Portugal; and

- (ii)

- the opportunity generated in rural areas as these are considered safer places and with lower possibility of diffusion of COVID-19 infection.

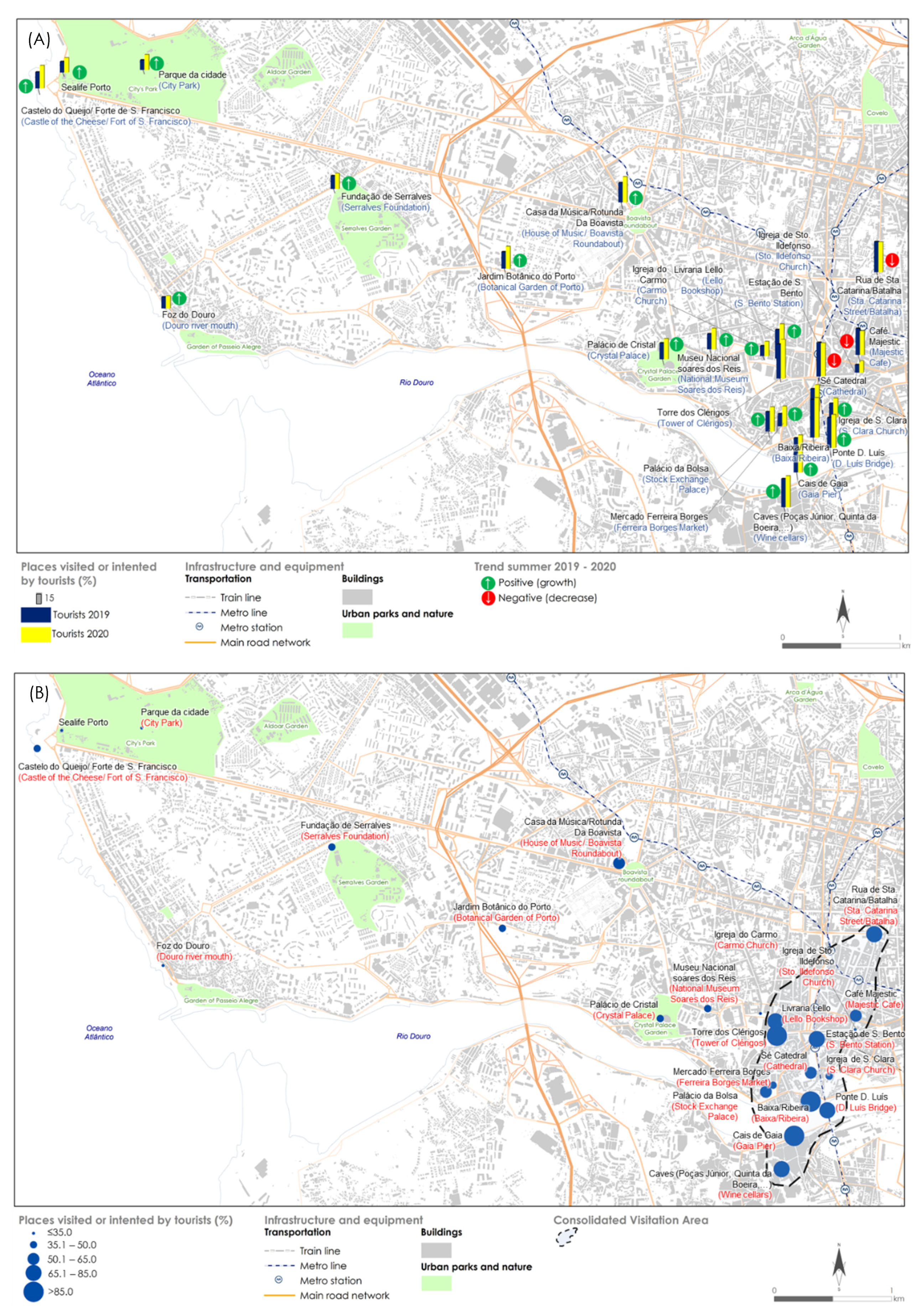

- (1)

- the identification of a central area—consolidated—that presented levels of intention to visit by tourists in any of the two years. This behavior is connected with the level of product maturity and the consolidated offer associated with these resources and/or attributes;

- (2)

- the identification of some tourist areas, whose structures would not be able to receive the same number of tourists in the year 2019 and in the year 2020. The reduction is much higher when it comes to locations respondents associate with the presence of many people.

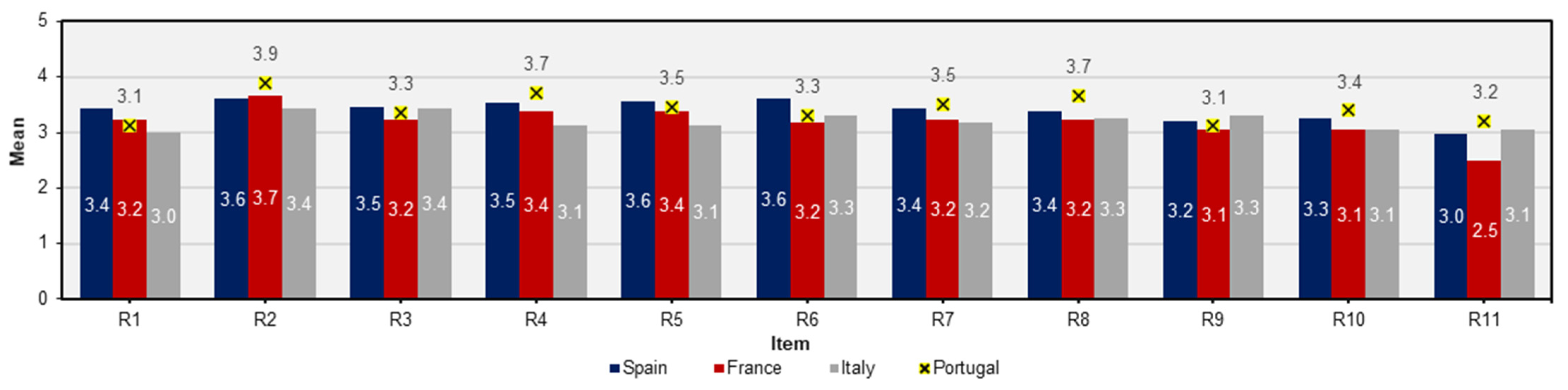

3.3. Risk Perceived by Tourists in Porto

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Promptness in the short-term reconfiguration of the strategy aimed at cities in the last decades based on mass tourism. It is essential to prioritize options based on the carrying capacity (less tourists) and based on shorter stays, the use of less means of transport (namely the plane—valuing domestic tourism) and the valorization of pre-existing resources and attributes in urban context.

- (2)

- Design models of action based on solutions to climate crisis. The pace of growth in the tourism sector reveals enormous environmental pressure on the planet [80], and it is now essential to define the priorities for action, based on balanced development or economic growth in the medium to long term. Among some of the most pressing interventions to reach sustainable development is the adoption of environmental codes to enter tourism destinations, in addition to accounting for the carbon footprint.

- (3)

- Define concrete plans for the restoration of the tourism sector in the short term. This intervention must start on a national scale (namely with the introduction of economic replacement measures for the entry of tourists already vaccinated against COVID-19 or the application of a guiding document for the recovery of the economic activity of tourism), but also at a local level, namely with the readjustment of planning instruments, the clear identification of areas of tourist decline during the COVID-19 period and of those which deserve special attention in a post-pandemic ‘new normal’.

- (4)

- Establish living areas in the city—small bubbles of green areas, which allow the connection between residents and tourists, but whose structures are spaced out to reduce concentrations. At an international level, it was proven during the first lockdown period and post-lockdown that the problems were aggravated as access to leisure areas and green spaces in cities were partially blocked and/or limited only to residents [27,76].

- (5)

- Establish links between different tourist segments, through promotion, dissemination, and marketing by regional and local entities. The solution may be to create visiting passports with a focus on the tourist profile—to allow for different experiences to be lived, but with greater control over the footprint at the destination and the maintenance of safety conditions in eventual health crises.

Future Research Directions

- (1)

- Identifying the key market trends in the post-pandemic tourism and more recurring basis. The study presented should also be carried out in other seasons of the year and in other phases of evolution of COVID-19, although this is not always viable in person.

- (2)

- Contributing with a prospective online study seeking to ask potential tourists about the desire to return a destination or the risk assessment after visiting certain destinations.

- (3)

- Analyzing the level of importance of socio-demographic, economic, and political-sectorial factors to trigger recovery actions. Each city/municipality/region can examine the essential determinants to cope with the consequences of the options and the obstacles caused in the tourism sector in the short, medium, and long term.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Davahli, M.R.; Karwowski, W.; Sonmez, S.; Apostolopoulos, Y. The hospitality industry in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Current topics and research methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC Economic Performance and Forecasts. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-performance-and-forecasts_en (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- OECD OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19): Rebuilding Tourism for the Future: COVID-19 Policy Response and Recovery. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-covid-19-policy-responses-and-recovery-bced9859/ (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- UNWTO 2020: Worst Year in Tourism History with 1 Billion Fewer International Arrivals. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilty, B.J.; Diamond, C.; Liu, Y.; Gibbs, H.; Russell, T.W.; Jarvis, C.I.; Prem, K.; Pearson, C.A.B.; Clifford, S.; Flasche, S. The effect of inter-city travel restrictions on geographical spread of COVID-19: Evidence from Wuhan, China. BMC Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. The unwanted free rider: Covid-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkowski, P.; Jażdżewska-Gutta, M.; Szmelter-Jarosz, A. Lockdowned: Everyday mobility changes in response to COVID-19. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 90, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Henriques, E. Arruinamento e regeneração do espaço edifìcado na metrópole do século XXI: o caso de Lisboa. EURE 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Tourism gentrification. In Handbook of Gentrification Studies; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rigolon, A.; Németh, J. “We’re not in the business of housing”: Environmental gentrification and the nonprofitization of green infrastructure projects. Cities 2018, 81, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gay, A.; Cocola-Gant, A.; Russo, A.P. Urban tourism and population change: Gentrification in the age of mobilities. Popul. Space Place 2020, 27, e2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Lopez-Gay, A. Transnational gentrification, tourism and the formation of ‘foreign only’enclaves in Barcelona. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3025–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R.; Parzych, K. Tourism Impacts, Tourism-Phobia and Gentrification in Historic Centers: The Cases of Málaga (Spain) and Gdansk (Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, J.M. The dispute over tourist cities. Tourism gentrification in the historic Centre of Palma (Majorca, Spain). Tour. Geogr. 2019, 22, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M. Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: Connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Santos, C. The impacts of COVID-19 crisis over the tourism expectations of the Azores archipelago residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, K.M. A post COVID-19 future-tourism re-imagined and re-enabled. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. The COVID-19 crisis, tourism and sustainable development. Athens J. Tour. 2020, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “war over tourism”: Challenges to sustainable tourism in the tourism academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A.; Lew, A.A.; Perez, M.S. COVID-19 is expanding global consciousness and the sustainability of travel and tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson-Fischer, U.; Liu, S. The Impact of a Global Crisis on Areas and Topics of Tourism Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Asymmetric impact of COVID-19 induced uncertainty on inbound Chinese tourists in Australia: Insights from nonlinear ARDL model. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M.; Bellini, N.; Rossi, S. Sustainability in Overtouristified Cities? A Social Media Insight into Italian Branding Responses to Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.-Y.; Yang, H.-W. The structural changes of a local tourism network: Comparison of before and after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napierała, T.; Leśniewska-Napierała, K.; Burski, R. Impact of geographic distribution of COVID-19 cases on hotels’ performances: Case of Polish cities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Black, K.J. Protection Motivation and the COVID-19 Virus. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change1. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itani, O.S.; Hollebeek, L.D. Light at the end of the tunnel: Visitors’ virtual reality (versus in-person) attraction site tour-related behavioral intentions during and post-COVID-19. Tour. Manag. 2021, 84, 104290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.S.; Mohammadi, Z.; Agarwal, M.; Kamble, Z.; Donough-Tan, G. Motivating or manipulating: The influence of health-protective behaviour and media engagement on post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.S.; Tiwari, A.K. Understanding international and domestic travel intention of Indian travellers during COVID-19 using a Bayesian approach. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu-Lastres, B.; Ritchie, B.W.; Mills, D.J. Travellers’ self-protections against health risks: An application of the full Protection Motivation Theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsuwan, S.; Rongrongmuang, W. Climate change perception of the dive tourism industry in Koh Tao island, Thailand. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badu-Baiden, F.; Adu-Boahen, E.A.; Otoo, F.E. Tourists’ response to harassment: A study of international tourists to Ghana. Anatolia 2016, 27, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippetoe, P.A.; Rogers, R.W. Effects of components of protection-motivation theory on adaptive and maladaptive coping with a health threat. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Boer, H.; Seydel, E.R. Protection motivation theory. Predict. Health Behav. 2005, 81, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.L.; Nair, V. Risk perception study in tourism: Are we really measuring perceived risk? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M.E. Why risk why now? Conceptual problems around the risk perception in tourism industry. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Em Tur. 2011, 5, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L. Consumer behaviour in tourism. Eur. J. Mark. 1987, 21, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W.S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. J. Travel Res. 1992, 30, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Understanding barriers to leisure travel: Tourist fears as a marketing basis. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinsöz, B.C.; Ege, Z. Impacts of perceived risks on tourists’ revisit intentions. Anatolia 2013, 24, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Sensation seeking and tourism: Tourist role, perception of risk and destination choice. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F.; Gibson, H.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Thapa, B. The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Zeng, X.; Morrison, A.M.; Liang, H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. A risk perception scale for travel to a crisis epicentre: Visiting Wuhan after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Watson, B. Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnšek, M.; Brumen, B.; Rangus, M.; Gorenak, M.; Mekinc, J.; Štuhec, T.L. Perceived threat of COVID-19 and future travel avoidance: Results from an early convenient sample in Slovenia. Acad. Tur. Innov. J. 2020, 13, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE População Residente (N.o) Por Local de Residência (NUTS—2013), Sexo e Grupo Etário. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&contecto=pi&indOcorrCod=0008273&selTab=tab0 (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Gomes, A.; Teixeira, J.; Fernandes, I. Geomorfologia. In Geografia do Porto; Rio Fernandes, J., Ed.; Book Cover Publisher: Porto, Portugal, 2020; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, L.; Bateira, C. Geomorphology in a World Cultural Heritage Site: The City of Porto. In Landscapes and Landforms of Portugal; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Custódio, D.; Cerqueira, M.; Alves, C.; Nunes, T.; Pio, C.; Esteves, V.; Frosini, D.; Lucarelli, F.; Querol, X. A one-year record of carbonaceous components and major ions in aerosols from an urban kerbside location in Oporto, Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 562, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, H.; Andresen, T.; Monteiro, A. Green structure and planning evolution in Porto. Urban For. Urban Green. 2011, 10, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. The Tourist-Historic City; Routledge: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 1136355804. [Google Scholar]

- Gusman, I.; Chamusca, P.; Fernandes, J.; Pinto, J. Culture and Tourism in Porto City Centre: Conflicts and (Im) Possible Solutions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE Inquérito à Permanência de Hóspedes na Hotelaria e Outros—Março 2021—Dados Preliminares. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0009812&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.; Ribeiro, V. Residents’ perceptions of tourism activity in a rural North-Eastern Portuguese community: A cluster analysis. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Lopes, H. O Turismo Como Alavanca do Desenvolvimento de Áreas Rurais: O Caso de Estudo do Município de Boticas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 1119165555. [Google Scholar]

- Remoaldo, P.; Freitas, I.; Matos, O.; Lopes, H.; Silva, S.; Sánchez Fernández, M.D.; Cadima Ribeiro, J.; Ribeiro, V. The Planning of Tourism on Rural Areas: The Stakeholders’ Perceptions of the Boticas Municipality (Northeastern Portugal). Eur. Countrys. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, T.G.; Tweeten, L.G. Research Methods and Communication in the Social Sciences; Westport, C., Ed.; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 0275949303. [Google Scholar]

- Ramires, A.; Brandao, F.; Sousa, A.C. Motivation-based cluster analysis of international tourists visiting a World Heritage City: The case of Porto, Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F.; Silva, O.; Amoedo, N. Urban tourist motivations in the city of Porto. Ottoman J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2019, 4, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, I.V.; Sousa, C.; Marques, J.; Ribeiro, S.; Yasar, S.; Pires, H. Tourism in Porto’s Historic Centre: Analysing Risks and Safeguarding of the Landscape. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Tourism Research, Porto, Portugal, 14–15 March 2019; p. 345. [Google Scholar]

- Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Brandenburg, C.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. City tourism pre-and post-covid-19 pandemic–Messages to take home for climate change adaptation and mitigation? J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.; Koopmans, M.; Go, U.; Hamer, D.H.; Petrosillo, N.; Castelli, F.; Storgaard, M.; Al Khalili, S.; Simonsen, L. Comparing SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV and influenza pandemics. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e238–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Adil, S.F.; Alkhathlan, H.Z.; Tahir, M.N.; Saif, S.; Khan, M.; Khan, S.T. COVID-19: A Global Challenge with Old History, Epidemiology and Progress So Far. Molecules 2021, 26, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, N.D.; Dunavan, C.P.; Diamond, J. Origins of major human infectious diseases. Nature 2007, 447, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P. Assessing tourism’s global environmental impact 1900–2050. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Summer 2019 | Summer 2020 | Total | Chi-Squared | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 207) | (n = 210) | (n = 417) | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 107 | 51.7 | 99 | 47.1 | 206 | 49.4 | 0.863 | 0.353 |

| Female | 100 | 48.3 | 111 | 52.9 | 211 | 50.6 | ||

| Age | ||||||||

| 15–24 | 22 | 10.6 | 20 | 9.5 | 42 | 10.1 | 7.865 | 0.164 |

| 25–44 | 146 | 70.5 | 141 | 67.1 | 287 | 68.8 | ||

| 45–64 | 31 | 15 | 44 | 21 | 75 | 18 | ||

| 65 or more | 8 | 3.9 | 5 | 2.4 | 13 | 3.1 | ||

| Country of residence | ||||||||

| Portugal | 35 | 16.9 | 43 | 20.5 | 78 | 18.7 | 31.125 | 0.000 *** |

| Other European country | 105 | 50.7 | 144 | 68.6 | 249 | 59.7 | ||

| Other Continent | 67 | 32.3 | 23 | 11 | 90 | 21.6 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Basic (Less than 6 years) | 7 | 3.4 | 3 | 1.4 | 10 | 2.4 | 4.358 | 0.36 |

| Basic (7th–9th year) | 20 | 9.7 | 16 | 7.6 | 36 | 8.6 | ||

| High School (10th–12th year) | 70 | 33.8 | 64 | 30.5 | 134 | 32.1 | ||

| Graduate | 81 | 39.1 | 100 | 47.6 | 181 | 43.4 | ||

| Postgraduate | 29 | 14 | 27 | 12.9 | 56 | 13.4 | ||

| Trip planning | ||||||||

| More than 1 year before | 7 | 3.4 | 8 | 3.8 | 15 | 3.6 | 7.875 | 0.344 |

| Between 12 and 6 months before | 15 | 7.2 | 8 | 3.8 | 23 | 5.5 | ||

| Between 5 and 2 months before | 61 | 20.4 | 73 | 34.8 | 134 | 32.1 | ||

| 1 month before | 21 | 10.1 | 31 | 14.8 | 52 | 12.5 | ||

| 15 days before | 29 | 14 | 31 | 14.8 | 60 | 14.4 | ||

| A week before | 40 | 19.3 | 33 | 15.7 | 73 | 17.5 | ||

| The day before the trip | 34 | 16.4 | 26 | 12.4 | 60 | 14.4 | ||

| Duration of visit | ||||||||

| 1 day (visitor) | 29 | 14 | 27 | 12.9 | 56 | 13.4 | 5.285 | 0.383 |

| 2–3 days | 98 | 47.3 | 106 | 50.5 | 204 | 48.9 | ||

| 4–6 days | 61 | 29.5 | 47 | 22.4 | 108 | 25.9 | ||

| 7–14 days | 17 | 8.2 | 27 | 12.9 | 44 | 10.6 | ||

| 15 and more days | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1.4 | 5 | 1.2 | ||

| Travel group size | ||||||||

| Alone | 37 | 17.9 | 16 | 7.6 | 53 | 12.7 | 24.078 | 0.000 *** |

| 2 people | 55 | 26.6 | 59 | 28.1 | 114 | 27.3 | ||

| 3 or 4 people | 66 | 31.9 | 93 | 44.3 | 159 | 38.1 | ||

| Between 5 and 7 people | 41 | 19.8 | 22 | 10.5 | 63 | 15.1 | ||

| Between 8 and 11 people | 7 | 3.4 | 16 | 7.6 | 23 | 5.5 | ||

| > 11 people | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 1.9 | 5 | 1.2 | ||

| Items | Mean 1 | Minimum 1 | Maximum 1 | Standard Deviation (S.D.) | Asymmetry | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1. Use of a mask in public places. | 3.181 | 2 | 5 | 0.816 | 0.349 | −0.309 |

| R2. Certification of hotels in relation to clean-safe practices in response to COVID-19. | 3.619 | 2 | 5 | 0.676 | −0.113 | −0.135 |

| R3. Spaces for restaurants, supermarkets, and large and airy stores. | 3.300 | 2 | 5 | 0.595 | 0.335 | 0.157 |

| R4. Minimum distance between people at attractions and tourism support sites. | 3.410 | 2 | 5 | 0.950 | −0.025 | −0.948 |

| R5. Number of daily COVID-19 cases | 3.386 | 2 | 5 | 0.738 | 0.256 | −0.153 |

| R6. COVID-19 signage adjusted to the needs in the public space and areas dedicated to tourism. | 3.319 | 2 | 5 | 0.683 | 0.223 | −0.011 |

| R7. Tours (guided) with security conditions adjusted to the current period. | 3.3429 | 2 | 5 | 0.608 | 0.172 | −0.108 |

| R8. Adequate hygiene conditions in visiting places and tourist facilities. | 3.419 | 2 | 5 | 0.615 | 0.686 | 0.073 |

| R9. Information on the procedures to be carried out at the place of stay, since entering Francisco Sá Carneiro Airport. | 3.129 | 1 | 5 | 0.756 | −0.084 | −0.590 |

| R10. Transport infrastructures with the necessary security conditions in response to COVID-19. | 3.219 | 2 | 5 | 0.712 | 0.458 | 0.313 |

| R11. On the street I feel safe. | 2.952 | 2 | 4 | 0.632 | 0.037 | −0.477 |

| Items | National vs. Foreign | European 2 vs. Non-European | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Foreign | T-Test | p-Value | European | Non-European | T-Test | p-Value | |||||

| Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | |||||

| R1 | 3.19 | 0.828 | 3.14 | 0.774 | −0.373 | 0.710 | 3.24 | 0.802 | 2.74 | 0.810 | 2.797 | 0.006 ** |

| R2 | 3.88 | 0.662 | 3.55 | 0.665 | 2.931 | 0.004 ** | 3.63 | 0.679 | 3.57 | 0.662 | 0.404 | 0.687 |

| R3 | 3.35 | 0.482 | 3.29 | 0.622 | 0.602 | 0.548 | 3.32 | 0.590 | 3.13 | 0.626 | 1.451 | 0.148 |

| R4 | 3.72 | 0.882 | 3.33 | 0.953 | 2.438 | 0.016 * | 3.41 | 0.942 | 3.43 | 1.037 | −0.135 | 0.893 |

| R5 | 3.47 | 0.667 | 3.37 | 0.755 | 0.791 | 0.430 | 3.40 | 0.736 | 3.30 | 0.765 | 0.560 | 0.576 |

| R6 | 3.30 | 0.638 | 3.32 | 0.697 | −0.179 | 0.858 | 3.36 | 0.685 | 2.96 | 0.562 | 3.193 | 0.003 ** |

| R7 | 3.51 | 0.593 | 3.30 | 0.606 | 2.056 | 0.041 * | 3.36 | 0.618 | 3.22 | 0.518 | 1.049 | 0.296 |

| R8 | 3.67 | 0.747 | 3.35 | 0.561 | 2.634 | 0.011 * | 3.42 | 0.621 | 3.39 | 0.583 | 0.229 | 0.819 |

| R9 | 3.12 | 0.793 | 3.13 | 0.749 | −0.119 | 0.905 | 3.13 | 0.751 | 3.13 | 0.815 | −0.012 | 0.990 |

| R10 | 3.40 | 0.695 | 3.17 | 0.711 | 1.831 | 0.068 | 3.23 | 0.730 | 3.13 | 0.548 | 0.632 | 0.528 |

| R11 | 3.21 | 0.559 | 2.89 | 0.635 | 3.047 | 0.003 ** | 2.96 | 0.638 | 2.91 | 0.596 | 0.316 | 0.753 |

| Items | Porto Is a COVID-Free Destination | Portugal Is a COVID-Free Destination | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | T-Test | p-Value | Yes | No | T-Test | p-Value | |||||

| Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | |||||

| R1 | 3.19 | 0.838 | 3.12 | 0.696 | 0.457 | 0.648 | 3.30 | 0.820 | 3.02 | 0.788 | 2.430 | 0.016 * |

| R2 | 3.64 | 0.694 | 3.52 | 0.566 | 0.961 | 0.337 | 3.67 | 0.732 | 3.55 | 0.585 | 1.342 | 0.181 |

| R3 | 3.35 | 0.585 | 3.03 | 0.585 | 2.882 | 0.006 ** | 3.34 | 0.627 | 3.24 | 0.547 | 1.299 | 0.196 |

| R4 | 3.44 | 0.916 | 3.24 | 1.119 | 0.960 | 0.272 | 3.43 | 0.978 | 3.39 | 0.915 | 0.299 | 0.765 |

| R5 | 3.40 | 0.701 | 3.30 | 0.918 | 0.582 | 0.563 | 3.41 | 0.665 | 3.35 | 0.831 | 0.537 | 0.592 |

| R6 | 3.32 | 0.642 | 3.30 | 0.883 | 0.118 | 0.907 | 3.29 | 0.674 | 3.36 | 0.698 | −0.802 | 0.423 |

| R7 | 3.36 | 0.625 | 3.24 | 0.502 | 1.201 | 0.235 | 3.36 | 0.656 | 3.32 | 0.537 | 0.515 | 0.607 |

| R8 | 3.44 | 0.619 | 3.33 | 0.595 | 0.871 | 0.385 | 3.43 | 0.692 | 3.40 | 0.492 | 0.449 | 0.654 |

| R9 | 3.15 | 0.747 | 3.03 | 0.810 | 0.812 | 0.417 | 3.13 | 0.760 | 3.13 | 0.755 | 0.058 | 0.954 |

| R10 | 3.26 | 0.691 | 3.00 | 0.791 | 1.938 | 0.054 | 3.18 | 0.750 | 3.27 | 0.656 | −0.928 | 0.355 |

| R11 | 3.00 | 0.640 | 2.70 | 0.529 | 2.561 | 0.011 * | 3.02 | 0.545 | 2.86 | 0.730 | 1.658 | 0.099 |

| Items | Visited Other Municipalities within NUTS III Área Metropolitana do Porto | Visited Other Municipalities Outside NUTS III Área Metropolitana do Porto | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | T-Test | p-Value | Yes | No | T-Test | p-Value | |||||

| Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | |||||

| R1 | 3.25 | 0.835 | 3.03 | 0.755 | 1.840 | 0.068 | 2.95 | 0.837 | 3.28 | 0.788 | −2.743 | 0.007 ** |

| R2 | 3.59 | 0.671 | 3.69 | 0.687 | −0.971 | 0.333 | 3.57 | 0.684 | 3.64 | 0.674 | −0.714 | 0.476 |

| R3 | 3.26 | 0.633 | 3.39 | 0.492 | −1.464 | 0.145 | 3.12 | 0.573 | 3.38 | 0.590 | −2.935 | 0.004 ** |

| R4 | 3.38 | 0.991 | 3.48 | 0.854 | −0.755 | 0.451 | 3.28 | 0.910 | 3.47 | 0.965 | −1.356 | 0.176 |

| R5 | 3.38 | 0.706 | 3.41 | 0.811 | −0.266 | 0.790 | 3.20 | 0.733 | 3.47 | 0.727 | −2.472 | 0.014 |

| R6 | 3.32 | 0.674 | 3.31 | 0.710 | 0.092 | 0.927 | 3.00 | 0.637 | 3.46 | 0.656 | −4.812 | 0.000 *** |

| R7 | 3.29 | 0.601 | 3.45 | 0.615 | −1.748 | 0.082 | 3.26 | 0.509 | 3.38 | 0.646 | −1.422 | 0.157 |

| R8 | 3.42 | 0.642 | 3.41 | 0.555 | 0.199 | 0.842 | 3.31 | 0.557 | 3.47 | 0.635 | −1.856 | 0.066 |

| R9 | 3.08 | 0.784 | 3.23 | 0.684 | −1.345 | 0.180 | 3.03 | 0.749 | 3.17 | 0.758 | −1.257 | 0.210 |

| R10 | 3.21 | 0.742 | 3.25 | 0.642 | −0.416 | 0.678 | 3.06 | 0.682 | 3.29 | 0.716 | −2.166 | 0.031 * |

| R11 | 2.90 | 0.584 | 3.08 | 0.719 | −1.771 | 0.079 | 2.89 | 0.687 | 2.98 | 0.606 | −0.879 | 0.382 |

| Items | Trip Planning | ANOVA F | p-Value | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More Than 1 Year Before | Between 12 and 6 Months | Between 5 and 3 Months | 2 Months Before | 1 Month Before | 15 Days | A Week Before | One Day Before | |||||||||||

| Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | Mean 1 | S.D. | |||

| R1 | 2.63 | 0.744 | 2.63 | 0.518 | 3.19 | 0.773 | 3.26 | 0.773 | 3.10 | 0.746 | 3.10 | 0.831 | 3.45 | 0.938 | 3.27 | 0.827 | 1.818 | 0.085 |

| R2 | 3.25 | 0.463 | 4.13 | 1.126 | 3.40 | 0.627 | 3.45 | 0.675 | 3.74 | 0.682 | 3.77 | 0.669 | 3.73 | 0.626 | 3.65 | 0.562 | 2.483 | 0.018 * |

| R3 | 2.88 | 0.641 | 3.13 | 0.641 | 3.19 | 0.594 | 3.10 | 0.473 | 3.48 | 0.769 | 3.42 | 0.502 | 3.39 | 0.556 | 3.42 | 0.504 | 2.381 | 0.023 * |

| R4 | 3.00 | 1.195 | 3.88 | 0.835 | 3.38 | 0.909 | 3.29 | 0.783 | 3.48 | 0.996 | 3.39 | 0.882 | 3.21 | 1.083 | 3.77 | 0.951 | 1.343 | 0.232 |

| R5 | 3.25 | 1.035 | 3.00 | 1.069 | 3.26 | 0.665 | 3.55 | 0.768 | 3.74 | 0.815 | 3.26 | 0.575 | 3.30 | 0.585 | 3.38 | 0.752 | 2.027 | 0.053 |

| R6 | 2.75 | 0.886 | 2.88 | 0.991 | 3.19 | 0.594 | 3.29 | 0.643 | 3.65 | 0.755 | 3.29 | 0.643 | 3.42 | 0.561 | 3.38 | 0.637 | 2.819 | 0.008 * |

| R7 | 3.50 | 0.535 | 3.00 | 0.756 | 3.29 | 0.636 | 3.29 | 0.739 | 3.48 | 0.677 | 3.39 | 0.495 | 3.21 | 0.485 | 3.50 | 0.510 | 1.264 | 0.270 |

| R8 | 2.88 | 0.641 | 3.50 | 0.756 | 3.45 | 0.670 | 3.48 | 0.570 | 3.48 | 0.677 | 3.35 | 0.486 | 3.48 | 0.619 | 3.35 | 0.562 | 1.191 | 0.309 |

| R9 | 2.50 | 0.926 | 2.38 | 0.518 | 3.12 | 0.550 | 3.03 | 0.752 | 3.16 | 0.969 | 3.13 | 0.718 | 3.36 | 0.742 | 3.35 | 0.629 | 2.949 | 0.006 * |

| R10 | 2.88 | 0.835 | 3.13 | 0.641 | 3.29 | 0.742 | 3.13 | 0.846 | 3.13 | 0.562 | 3.13 | 0.619 | 3.18 | 0.584 | 3.62 | 0.804 | 1.760 | 0.097 |

| R11 | 2.63 | 0.518 | 3.00 | 0.535 | 2.93 | 0.640 | 2.61 | 0.667 | 3.06 | 0.574 | 3.13 | 0.670 | 3.03 | 0.585 | 3.04 | 0.599 | 2.323 | 0.027 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116399

da Silva Lopes H, Remoaldo PC, Ribeiro V, Martín-Vide J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116399

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva Lopes, Hélder, Paula C. Remoaldo, Vitor Ribeiro, and Javier Martín-Vide. 2021. "Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116399

APA Styleda Silva Lopes, H., Remoaldo, P. C., Ribeiro, V., & Martín-Vide, J. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability, 13(11), 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116399