Abstract

There are multiple factors that can potentially impact the career progression of academics to professoriate level (referred to as levels D and E in Australia). This research provides a detailed understanding of critical factors (by gender) that negatively influence career progressions. Perceptions of factors that influence career progressions have been found to be more pronounced amongst female academics in STEMM and business disciplines. The conventional view of family commitments as being a hindrance to career progression has not been supported in our data. On the contrary, it is the organizational factors that would appear to be prevalent at an institutional level that seems to be significant barriers to the career progression. Particularly for female academics’ progression to levels D and E. The most prominent factors identified through confirmatory factor analysis conducted in the study are workloads and a lack of resources to undertake research and to generate research performance, which is a critical impacting factor for career progression to professoriate levels. These factors have been exacerbated by COVID-19.

1. Introduction

Women make up 70 percent of persons in education and training. Yet, only 45% of Australian women hold senior lecturer faculty positions and 32% hold “above senior lecturer” faculty positions [1]. In relation to management tiers, women occupy 25 percent of tier-one management, 39 percent of tier-two and 36 percent of tier-three management positions [2].

The Australian government has been promoting the agenda of more women in leadership positions at Australian Universities. Universities around Australia are responding to this call and are reviving gender equality and diversity policies. The revitalizing is primarily occurring in the STEMM faculties because of the national government agenda of promoting women in this sector. The impacts of these initiatives are flowing on to business disciplines as well. There is a general perception that the career progression of women is not actually an issue in business disciplines. Yet data indicates that gender equity at the professoriate level is an issue in STEMM and business disciplines.

There are multiple factors that have been found to hinder the career progression of females. This article aims to explore the factors that hinder the career progression of academics and to determine if these are gendered factors. To address this aim, the research questions addressed are: what are the barriers to academic career progression from a resource allocation perspective; and whether these barriers are gendered, that is, more pronounced for female academics? To address these questions, a survey of academics in associate lecturer, lecturer and senior lecturer roles in STEMM and business disciplines has been undertaken.

Research output, whether it is learning and teaching-related or not, is a critical factor for achieving promotion to associate professor and professor levels in Australian academia. Resource allocation to research is necessary to accomplish the required research output. Essential resources can be classified as different types to achieve the objective of these required research output. Types of resources, their availability (or lack thereof) and their potential impacts are explored through the gender lens and by applying confirmatory factor analysis. It is important to note that COVID-19 has negatively impacted productivity and scientific output of female academics disproportionately [3]. COVID-19 continues to threaten progress for gender equity by exacerbating existing gender parities [3].

The key contribution in this article is the determination of whether resource allocation is a gendered issue or is resource allocation a critical problem for all academics regardless of gender. Additionally, if resource allocation is a gendered problem, then we propose it to be a higher risk gendered problem due to COVID-19. From this perspective, this article adds to gender literature by reiterating the importance of institutional factors in impacting the career paths of academics in the higher education sector.

2. The Australian Context

Universities remain a cornerstone of Australia’s economic success [4]. In 2018, universities contributed $41 billion to the Australian economy and supported a total of 259,100 full-time jobs. Notably, 325,171 students completed their degrees at Australia’s 39 universities. In 2018, Australia’s 39 comprehensive universities employed 131,588 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff. Total FTE staff count has grown by 29.4 percent, from 101,656 in 2008. Over the same period, the growth in academic and professional or non-academic staff was similar at around 29 percent. Since 2001, academic staff have consistently made up around 40–46 percent of all university staff FTE [4]. Following Table 1 shows the academic gender staffing profile in 2008 and 2017 [4].

Table 1.

Academic gender staffing profiles by classification 2008–2017.

The Australian Government introduced legislation into Parliament in March 2012 to retain and improve the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace (EOWW) Act and the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency. The EOWW Amendment Bill successfully passed through Parliament on 22 November 2012. The act is called the Workplace Gender Equality Act (the Act) and the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency is now the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (the Agency). The Agency is an Australian Government statutory agency that promotes and improves workplace gender equality and administers the ACT [5].

The principal objects of the Act are: [6].

- To promote and improve gender equality (including equal remuneration between women and men) in employment and in the workplace;

- To support employers to remove barriers to the full and equal participation of women;

- In the workforce, in recognition of the disadvantaged position of women in relation to employment matters;

- To promote, amongst employers, the elimination of discrimination on the basis of gender in relation to employment matters (including in relation to family and caring responsibilities);

- To foster workplace consultation between employers and employees on issues concerning gender equality in employment and in the workplace;

- To improve the productivity and competitiveness of Australian business through the advancement of gender equality in employment and in the workplace.

Universities individually report to the Agency under the Act, which also includes a gender equity action plan (GEAP). The GEAP assists with planning, implementing and measuring changes within the university achieving gender equality. The universities need to apply to the Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner to have GEAP accepted as meeting the requirements of the Act [5].

Further, most universities in Australia are subscribers of Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE) Ltd., which is a not-for-profit public company, which administers the unique Athena Swan gender equity and diversity national accreditation framework. Founded by the Australian Academy of Science and the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering, the vision of SAGE is to improve gender equity in the Australian higher education and research sector. It is the unprecedented gender equity and diversity program in Australia that develops a sustainable and adaptable Athena Swan model for the country [7].

Established in 2005 in the UK, the Athena SWAN Charter progressed from the work of the Athena Project and the Scientific Women’s Academic Network (SWAN). It is an enabling mechanism for gender equity, providing a framework in which to plan and undertake solid work to create structural and cultural change for gender equity. The Athena SWAN is particularly relevant to Australia due to similarities that exist between Australian and UK academic, scientific and research sectors, combined with its systematic and evidence-based approach. SAGE has facilitated three cohorts, a total of 45 institutions, to commit to their Athena Swan Awards pathway. The SAGE has been supported by the Australian Government, SAGE subscribers and sponsors [7].

3. Literature Review

In academic institutions, there is a greater focus on achievement (attainment of status, prestige and recognition) in comparison to affiliation. As a result of the power differential and under-representation of women in senior positions, there can be a feeling that organizational support such as in the form of mentoring or availability of resources is absent. References [8,9,10] a lack of access to networks is considered a significant barrier against career progression as opportunities for senior-level positions are circulated in these networks. There is a general perception that most senior positions are rarely advertised and filled by people tapped on the shoulder through their networks [11].

Self-evaluation of the social climate of the workplace negatively [12] or experiencing the effects of hierarchy [13] are critical factors, which can negatively impact career progression.

Marginalization results in the segregation of individuals or groups over an extended period. Literature has found that women in academia are more likely than men to be in lower-ranked positions in higher education institutions [14], and women are under-represented in senior academic ranks [15]. Interestingly, publication rates are more strongly correlated with academic rank than gender [16]. Academic rank, in turn, is impacted by publication rates, and as identified below, resource constraints act as a significant barrier against research performance where major determinant being publications and citations. Resource constraint has been defined as the deficit model, which argues that female academics’ research productivity might suffer due to the availability of lesser opportunities throughout their careers [17].

3.1. Importance of Research Output/Performance on Academic Career Progression

Prior research evidently indicates the only requirement for research output in the promotion criteria to higher university levels [18,19]. Three measures of research output are evaluated [20]. Firstly, recognized publications that are assigned values as per the requirements of Department of Education Science and Training (DEST) system (DEST, 2005) [21], which includes book chapters, conference papers and journal articles. Secondly, the total Australian dollar value of research funding and finally, the number of successful research grants.

Academics globally have been confronted with workload challenges during the last two decades, which have brought significant workload changes, with the feeling that an academic today in tertiary education needs to fulfil three full-time jobs—research, teaching and leadership service [22]. In Australia, a typical academic workload is defined as: 40 percent research; 40 percent teaching; 20 percent service with administrative responsibilities allocated under each of those three roles [19]. Thus, academics feel they need to manage continuously the multiple and changing functions associated with the current academic workload [22]. However, these tasks and roles are not recognized [23]. Attainments in research performances remain a foremost requirement in the criteria for promotion to higher academic levels and are also perceived by the staff as pivotal for promotion over teaching [18,24]. The Australian higher education reform focuses on these broad themes, namely: increased participation, teaching and research excellence and achieving equity outcomes [23]. Thus, academics are expected to perform both in teaching and research, with research given more weight than teaching in the evaluation of academic work [25,26]. The possibility of an academic being promoted internally was related to the number of academic papers published as measured by DEST output, while no valuation for teaching was observed [19]. The results of their study provide empirical support highlighting the importance for academics to publish. Self-promotion through performance comparisons is also possible and is an avenue for further consideration for academic staff seeking to manage their research identities, the impact of their research and individual reputations [19].

However, it is implied that there are gender inequalities in the teaching-research nexus, and these inequalities can have negative career progression impacts for female and male academics [18,26]. Further, prior research indicates that female academics already form a disadvantaged group in academia since they are underrepresented in senior academic positions [27,28,29].

Drawing on an intersectional approach, scholars examined how gender and foreignness act as dynamic, interrelating categories in producing subjectivities in the context of the U.K. business schools [30]. They found that the academic career path of uninterrupted progression, research activity and networks follow a masculinist norm. Further, they claim that academic achievement is assessed on the quality of the academic’s research and is not nationality, gender or age-dependent, that it is merit-based. In contrast, some other researchers claim that the shifting teaching research nexus is likely to introduce a constraint on career progression for female academics, as they tend to be more heavily involved in teaching than in research or leadership in comparison with their male counterparts [31]. They further state that the disproportionate division between teaching and research roles in academia can produce gendered segregation of academic roles and thus operate as a barrier to the career progression of female academics, as success in research remains one of the most important criteria required for promotion to higher-ranked academic positions. This will result in a more distinct propensity among female academics to have unbalanced work portfolios [31]. These are hard to compensate for by devoting time to research after working hours due to domestic responsibilities of parenting and care. Gendered processes also impact access to mentorship and joint research project networks [32] since these networks are sustained by gendered support systems [33]. The cumulative effect of these intertwined developments is that women will find themselves with less time for research activities, which may lead to fewer research outputs and therefore, to possible disadvantages in their career development [18]. For women at mid-career levels, such as those at the levels of assistant and associate professor, where the criteria for career progression are significantly demanding with respect to research outputs, the workload imbalance disadvantaging research may mean stagnation or disruption of an academic career path [25].

The demand for accountability and performance in terms of research outputs, coupled with the increased competition for resources, has led to changes in the teaching-research nexus and a disproportionate allocation of different tasks at different career levels for female academics [34]. To cope with the growing demands on performance and efficiency, universities in various countries have introduced a differentiation of career paths in terms of teaching-only and research-only positions [35]. Similarly, findings of a study [36] suggest that generally, females need to improve their research productivity, particularly in the refereed publications category, and review their level of involvement in teaching (including flexible delivery development) and administrative leadership duties.

3.2. Research Performance for Academic Career Progression and Resource Limitations

Prior research has found that productivity levels across gender are materially different: women faculty members have been found to publish less than male colleagues [15,37]. Studies found that females in academia wait twice as long as men to get promoted or that women do not advance as quickly as men as they enter positions that have a lesser potential for promotion and tenure [15,38] and this results in female academics publishing less than male academics. Women are more likely to work part-time, remain at the bottom of the academic hierarchy, with lesser salaries, greater teaching loads, administrative duties and less research productivity than men [39]. Gender intensification has been observed as women being over-represented in teaching roles and women, finding it difficult to achieve promotion due to not meeting research performance metrics [40]. Although the higher education sector perceives the flexible, family-friendly work environment, research performance expected for promotion is based on full-time continuous careers [41].

Researchers have found that female faculty’s involvement in research has been less than that of male colleagues (at junior, less than associate professor level) in the medical discipline [42]. The main factor contributing as a resource constraint towards research performance has been low self-ability, which has been found to be gendered. Low self-ability is created by cultural and societal expectations and family responsibilities faced by females in comparison to males [43]. Lack of time as a resource constraint has also been identified as a critical barrier against research performance [44]. Different preferences such as females emphasizing student quality, teaching, collegiality and interaction within the department compared to males ranking salary, benefits and research time have been identified as critical behavioral factors that impact research performance [45].

Lack of access to networks or mentoring is a resource allocation and access problem. Another critical factor that could be gendered is the availability of financial resources, which are required to research materials (for example, databases) and technologies [46]. Research output itself is classified as a critical resource in the form of impact, publications, student supervision and funding with a strong feedback loop in which success is met with further success for financing example is needed to undertake research and funding is awarded based on the track record of research output [47]. Through autoethnographic accounts of four female staff members, explore the intersection of gender and location through case studies of personal experiences, investigating the impacts of distance and travel limitations can have on participation in networking events, access to professional development opportunities and career progression within the university.

3.3. Resource Constraints Gendered?

The system of academic promotion is merit-based and requires the achievement of adequate research output and performance (at most higher education institutions in Australia), which in return require resources. According to the constructionist approach, gender, class or ethnicity simultaneously provide narrative and enabling resources [48] (p. 280). Women, and particularly women of color, may face resource constraints due to the intersectionality of gender and race [49,50]. In the U.S. context, researchers [51] have found that there is a disproportionate leaning towards female adjunct professors in American universities compared to males. Adjunct professors lack access to basic, taken for granted resources such as offices and computers. The lack of such basic resources naturally limits mostly female adjunct professors from going down the path of tenure-track positions as these basic resources are a definite requirement for undertaking and publishing research (ibid.) Adjunct, part-time positions with lesser expectations for teaching and research could be the preferred path for PhD female graduates with young families and family responsibilities [51]. Further, it can be assumed that for a PhD graduate, a non-teaching position may imply a research-focused, post-doctoral position.

O’Brien and Hapgood [47] have found that strategy as a resource can be utilized by female academics to overcome barriers against career progression. Such strategies include: becoming part of a collaborative research team, working with established researchers, finding opportunities to build expertise and connections while being time-efficient, selecting mentors who would be of benefit and undertaking effective time management [51]. From an institutional perspective, recommendations to increase women’s participation at senior levels include: flexible application of metrics rather than strict adherence to metrics; provision of funding schemes specifically for women who are returning to research after a career break; removal of institutional, bureaucratic barriers, which should allow greater participation of women in PhD student supervision and applying for funding; involvement in other initiatives resulting in higher research performance [52].

3.4. COVID-19 as a Facilitator of Reduced Research Output for Female Academics

Prior research has highlighted how preprint submissions for multiple STEMM and business disciplines have although increased during COVID-19, the number of male authors continue to grow at a much faster rate compared to female authors [53]. Researchers further found [54,55] dramatic reduction in preprints from female economists during COVID-19.

Key underlying reasons for decreased outputs during COVID times from female academics include women spending more time on child care, home schooling, increased gendered domestic labor and enhanced institutional biases against women relating to research allocation, outcomes of reviews and number of citations [3]. A large survey of more than 4000 principal investigators at U.S. and European institutions found that being female with children were the most significant factors to impact research disruptions during COVID-19 [56].

4. A Theory of Gendered Organizations

4.1. Gender

The belief that social structure and social processes are gendered has emanated in diverse areas of feminist discourse [57,58,59]. Gender has evolved as a concept with its social construction, which implies the assigning of roles, responsibilities and characteristics and stereotypical imaginations to two specific genders: males and females [60]. Gender is defined as: “………an integral connection between two propositions: gender is a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes and gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power” [61] (p. 1067). Similarly, Acker defines gender as “a foundational element of organizational structure and work life, present in its processes, practices, images and ideologies and distributions of power” [62] (p. 567). “Gender is a constitutive element in organizational logic, or in the underlying assumptions and practices that construct most contemporary work organizations” and asks for challenging traditional organizational practices around gender [63] (p. 147).

4.2. Organizational Logic

Organizational logic appears to be “gender-neutral theories of bureaucracy that organizations employ and give expression to them as logic[al]” [64] (p. 147). There is a misleading perception of gender neutrality in written work rules, labor contracts, managerial directives and other documentary tools, including systems of job evaluation widely used.

In organizational logic, both jobs and hierarchies are abstract categories that have no occupants, no human bodies and no gender [65]. Nevertheless, an obscure job that exists can be transformed into a concrete instance only if there is a worker. Filling the abstract job is a disembodied worker who exists solely for the work. Such an imaginary worker cannot fulfil organizational requirements and performance targets and have other external requirements of existence that interrupt the job. At the very least, external requirements cannot be included within the definition of the job. Too many obligations outside the boundaries of the job would make a worker unsuited for the position [62].

Hierarchies are gendered because they also are constructed on these underlying assumptions: “Those who are committed to paid employment are “naturally” more suited to responsibility and authority; those who must divide their commitments are in the lower ranks. Job evaluation systems were intended to reflect the values of managers and to produce a believable ranking of jobs based on those values. Such rankings should not deviate substantially from rankings already in place that contain gender stereotyping and gender segregation of jobs and the clustering of women workers in the lowest and the worst-paid jobs” [63] (p. 150).

Accordingly, a congruence between responsibility, job complexity and hierarchical position is assumed by organizational logic [63]. For instance, a lower-level position, which is the level of most jobs filled predominantly by women, must have equally low levels of complexity and responsibility. Complexity and responsibility are defined in terms of managerial and professional tasks. These definitions induce gender as an analytic category [61] and is an attempt to find novel avenues into the complicated problem of explaining the phenomenal persistence through history and across societies of the subordination of women.

4.3. Organization as a Gendered Process

Acker’s formal statement of a ‘theory of gendered organizations’ examines organizations “as gendered processes in which both gender and sexuality have been obscured through not only perceived gender-neutral policies, processes and expectations but also through asexual discourse and the implementation of the use of gender, the body and sexuality for implementing controls in organizations” [63] (p. 146). Acker [63] further argues that an organization is gendered is to say “that advantage and disadvantage, exploitation and control, action and emotion, meaning and identity, are patterned through and in terms of a distinction between male and female, masculine and feminine”. That is to argue that an organization is inherently gendered implies that “they have been defined, conceptualized and structured in terms of a distinction between masculinity and femineity and will thus inevitably reproduce gendered differences. Ultimately, to the extent that gendered characteristics are differently valued and evaluated, inequalities in status and material circumstances will be the result” [64] (p. 419). Accordingly, gender is not an addiction to ongoing processes, considered gender-neutral. Relatively, it is an integral part of those processes, which cannot be adequately understood without an analysis of gender [65].

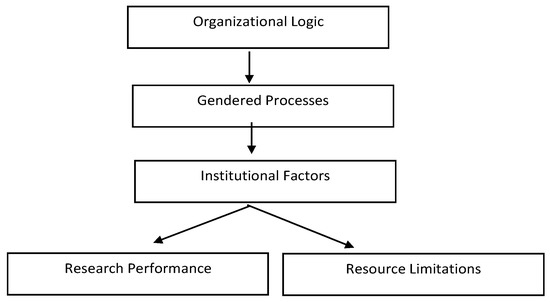

The gender-neutral status of a job and of the organizations of which it is a part of unfairly depends upon the assumption that the worker is abstractly disembodied. However, in actuality, both the concept of a job and real workers are profoundly gendered and bodied. Additionally, so are distributions such as power and authority, access to resources and ranks in organizations. In other words, organizations purport that policies, processes and expectations are gender-neutral, which sounds like a very logical, unbiased argument supportive of gender equality. Yet, policies, processes and expectations are gendered. They are defined mostly in very masculine terms in higher education research settings, for example, as rankings of journals or as quantitatively determined impact factors or merely several citations. There are inherent biases in systems that require careful considerations and attempts to undertake genuine changes towards recognizing feminine forms of performance and output on par with masculine representations. Figure 1 below captures the issue of ignoring the gendered nature of processes and factors, which have a profound impact on the career progression of female academics based on research performance, which is impacted by availability (lack thereof) of resources due to gendered biased processes, systems and evaluations.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework. Source: Developed by the authors for the study based on Acker (1990).

4.4. Fourth-Wave Feminism in the Face of COVID-19

A potential solution to the problem of institutional biases, exacerbated by COVID-19, against women is the use of the Internet to challenge sexism and misogyny as they appear is every day rhetoric [65] or in masculine performance measurements such as the expectations to not only publish but to publish in highly ranked discipline specific journals.

The fourth wave promotes the challenging of established systems of power, it requires power to serve collaboration, not conquest, to encourage support not competition [66]. Fourth wave feminism combines politics, psychology and spirituality to recognize the complexities associated with unconscious (bias) dynamics and organizational realities to understand social inequalities associated with individual issues [67]. Constructive measures, from a fourth wave feminism perspective could include development of women centered research networks, better resources for co-operation and higher co-authorships [68,69].

5. Research Method

A survey approach was adopted in this research in 2017/18 to attain perceptions of academics in STEMM and business disciplines across Australian universities to understand if there were gendered differences between perceptions regarding resource allocations and access. Additionally, to determine whether resource access is perceived to have a material impact on an academic’s career progression. The survey is preferred since it is deemed to be the most effective method for a geographically dispersed population. Using a survey instrument for the purposes of obtaining data for research purposes is a common and popular methodology in business, management and accounting research, and is the most frequently used to answer ‘who, what, where, how much and how many’ type questions [70]. A survey refers to an investigation where systematic measurements are made over a series of cases, yielding a matrix of data; the variables in the matrix are analyzed to see whether they show any patterns; and the subject matter is social in nature. Surveys can be divided into two types: they can either be descriptive or analytical. Analytical surveys intend to examine relationships between specific variables, whereas descriptive surveys are used in order to represent phenomena at a particular instance or at various instances [70]. The survey used in the current study is a descriptive.

The initial sample of the survey consisted of 645 respondents in continued positions in STEMM and business disciplines in Australian Universities. After removing missing responses for the gender variable, 583 responses were included in the analysis. In the final sample, 50.3% of responses were representative of senior lecturers (C level), 45.6% was representative of lecturers (Level B) and the rest of the 4% of the sample was representative of associate lecturers (level A). See Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Respondents.

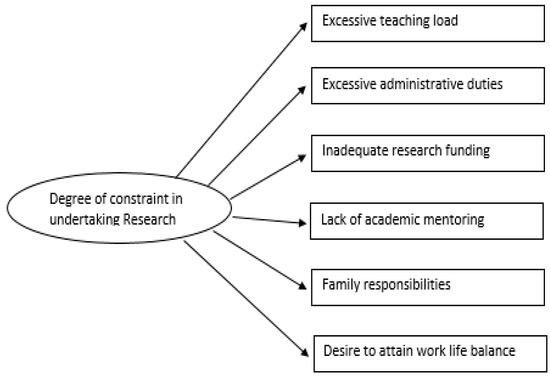

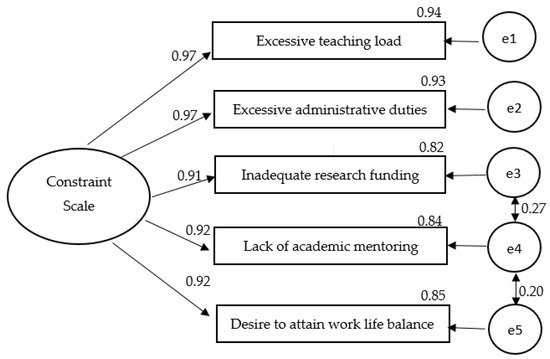

The following Figure 2 shows the one-factor model with six items for the scale of “degree of constraint in undertaking research”.

Figure 2.

Degree of constraint in undertaking research.

The hypotheses tested are:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Excessive teaching load has a negative impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Excessive administrative duties have a negative impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Inadequate research funding has a negative, significant impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Lack of academic mentoring has a negative, significant impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Family responsibilities have a negative significant impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Desire to attain work–life balance has a negative significant impact on undertaking research.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

The factors which impact as constraints for undertaking research are more pronounced in the case of female than male academics.

6. Analysis and Results

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

Male and female respondents have equally participated in the survey comprising of 49.2% and 50.8% of the sample, respectively. Approximately 35% of the respondents worked as an academic overseas before joining academia in Australia. Nearly 50% of the respondents had academic work experience of more than ten years, and from those who had work experience in the industry (82%), 63.4% had work experience relevant to their own discipline. See Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 below.

Table 3.

Gender affiliation.

Table 4.

Academic work experience.

Table 5.

Industry work experience.

Table 6.

Academic and industry work experience as a total.

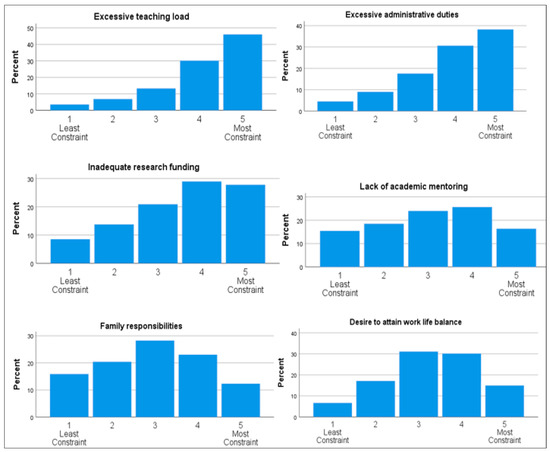

6.2. Analysis of Constraints on Undertaking Research

The following bar charts in Figure 3 show the percentages of responses for constraints. Items excessive teaching load, excessive administrative duties and inadequate research funding had the highest percentage (>50%) of responses for those as a constraint (4) and most constraint (5) for the degree of constraint in undertaking research. In the items a lack of academic mentoring and desire to attain work–life balance, most of the responses varied between neutral constraint (3) and constraint (4). In contrast with the other items, family responsibilities were not considered as a constraint by most of the respondents in the survey.

Figure 3.

Percentages of responses for constraints.

6.3. Constraints as Per Gender and Work Experience Groups

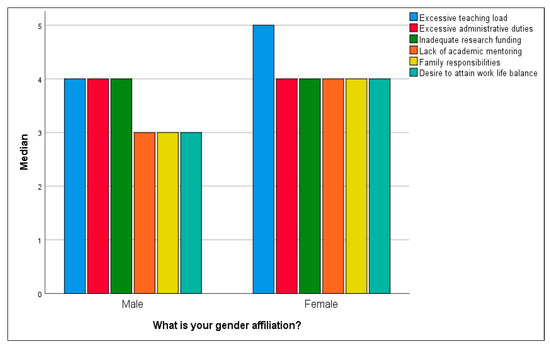

The following section presents the median constraint level for each item according to the gender and work experience categories.

- i.

- Gender

Overall female respondents had high median constraint levels for all items in the scale, compared to the male respondents (see Figure 4). According to the female respondents, “Excessive working load” is the most constraint (median scale = 5) on undertaking research. The median constraint levels of a lack of academic mentoring, family responsibilities and desire to attain work–life balance of male respondents were lower (median scale = 3) than the female respondents (median scale = 4).

Figure 4.

Gender.

- ii.

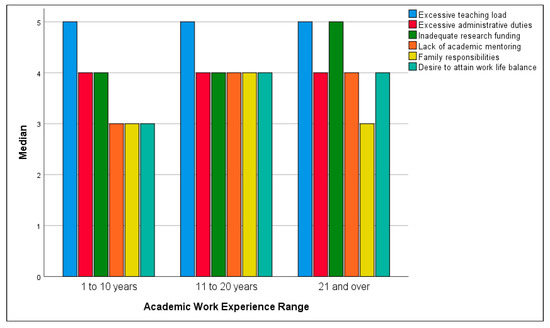

- Academic work experience

Regardless of the length of academic work experience, (see Figure 5) excessive teaching load had the highest median constraint (median = 5). Respondents who had academic work experience over 21 years consider inadequate research funding (median = 5) as the highest level of constraint on undertaking research. The median constraint level for family responsibilities of respondents who had academic work experience between 11 and 20 years was higher than for the other two levels of work experience.

Figure 5.

Academic work experience.

- iii.

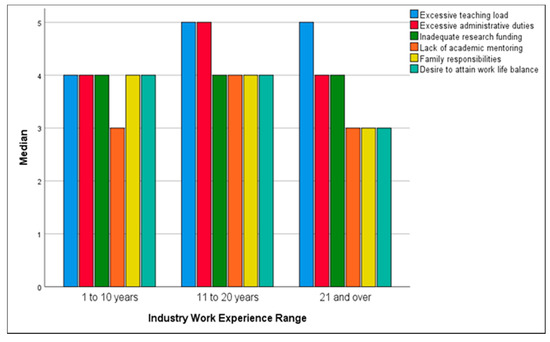

- Industry work experience

From the respondents who had industry working experience (see Figure 6), the median constraint level for lack of academic mentoring was less than for the other measured constraints in undertaking research for academics with 1–10 years and 21 and overwork experience. Respondents who had industry work experience over ten years considered excessive teaching load to have the highest constraint level (median = 5). Responders who had industry work experience between 11 and 20 years considered excessive administrative duties also to have the highest constraint level (Median = 5).

Figure 6.

Industry work experience.

- iv.

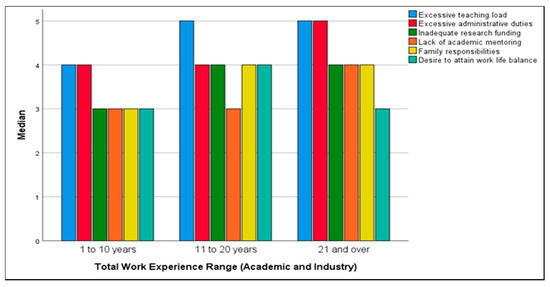

- Total Work Experience range

According to the respondents who were having less than 10 years of total work experience, (see Figure 7) median constraint level for excessive teaching load and excessive administrative duties were higher than that of the other constraints towards undertaking research. For academics with a total work experience of more than ten years, excessive teaching load remained as the highest-ranked barrier against undertaking research.

Figure 7.

Total work experience range.

6.4. Structural Equation Modeling: One Factor Model for the Degree of Constraint in Undertaking Research

Hypothesized factor structure containing six items was tested with the factor validity, using Cronbach’s alpha in the first stage. Cronbach’s alpha is an assessment of how reliable the survey items that are designed to measure the same construct are. Cronbach’s alpha for the 6 item factor structure was 0.925 (>0.7), which is an adequate measure for internal consistency. However, according to the item-total statistics, Cronbach’s alpha increased if item family responsibilities were deleted from the constraint scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.953).

Hence stage two of the analysis was carried out based on the one-factor model containing five items by removing constraint family responsibilities. The factor structure of 5 items was generated using AMOS, with the estimation method of maximum likelihood. After improving the model considering the fit indices and modification indices, the final model (Figure 8) was created.

Figure 8.

Research output constraining factors.

Chi-square test of the absolute fit value of 6.218 (df = 3, p = 0.101 > 0.05), indicated that the data was a good fit for this structured model. Since the chi-square test was usually biased with the sample size of the data, relative fit indices were also generated to measure the model fit further. Relative fit indices results: TLI = 0.998 (>0.95), CFI = 0.998 (>0.99) and RMSEA = 0.041 (<0.060) suggest that the data fits the five factor model well. Hence, we could use the model to interpret the contribution of each item to the degree of constraint in undertaking the research scale.

According to the standardized regression weights, both excessive teaching load (0.967) and excessive administrative duties (0.966) had the highest degree of constraint in undertaking research. Following these constraints, inadequate research funding (0.906), desire to attain work–life balance (0.918) and a lack of academic mentoring (0.923) also having a high degree of constraint in undertaking research. Inadequate research funding is the least degree of constraint among all these constraint items towards the constraint scale.

According to the constraint scale model, there are also two covariances existing between e3, e4 and e6. These suggest that there was a different relationship between inadequate research funding and desire to attain work–life balance (e3-e4 = 60.624, p < 0.05)) and also between desire to attain work–life balance and a lack of academic mentoring (e4-e6 = 40.71, p < 0.05), which were not able to be explained from this five-item constraint factor model. According to squared multiple correlation figures, 93.5% of the constraint scale can be explained by using excessive teaching load as an item. A total of 93.3% of constraint scale can be explained by using excessive administrative duties as an item, 82% of the constraint scale can be explained by using inadequate research funding as an item, 84.2% of constraint scale can be explained by using desire to attain work–life balance as an item and 85.2% of the constraint scale can be explained by using a lack of academic mentoring as an item.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper is a critical addition to the growing literature, which highlights the risk of reversion of the limited female academic career progress initiated pre-COVID-19 in higher education. STEMM and business disciplines face an increased exposure to gender inequality, especially at senior levels; it is exacerbated by COVID-19. This research and other literature acts as warning signs for HE management regarding the increased gender inequality at senior levels in academia. It is intended that the current research creates at least some level of consideration regarding the limitations and the inequality associated with masculine performance measures including the expectation of (in some instances politicized) “high quality, high ranked” research outputs, which seem to have attracted more attention now in the COVID-19 environment.

As identified in this article and prior research career progression of women in academia to higher levels is strongly impacted by excessive workloads, which can disadvantage women much more than men through different interactive factors [18]. These factors negatively influence research activity, which is a central area for progression to higher levels in academia (ibid.) Inclination towards being research active started in 1989 when the Australian Unified National System of Higher Education allowed the number of publicly funded universities to more than double [71]. Teaching and professional training staff were encouraged to engage in research and the expectation of research engagement extended to new disciplines and to long-established disciplines such as accounting and law [71]. Research evidenced in funding replaced scholarship as the primary mechanism for promotion (ibid.). At present, COVID-19 has had a severe negative impact on female academics’ research output and performance [72,73].

Research funding has been found to be an issue that impacts research activity for all academics regardless of gender. The main reasons identified include a very high demand, a greater number of academics seeking funding and increased pressure to obtain centralized, external project funding [72]. As far as administrative responsibilities are concerned, prior research has found that senior female academics carry a heavy load of university committee memberships [39,71], which has a negative impact on research performance and career progression. Our data has suggested that regardless of gender, the administrative load is considered a burden and a research constraint. Nevertheless, female respondents have been found to have higher median constraint levels for all items on the scale, compared to the male respondents. According to the female respondents “Excessive working load” is the most constraint (median scale = 5) on undertaking research.

The greater sensitivity of female academics to teaching loads, administrative duties, the desire to achieve work–life balance and the negative impact of lack of academic mentoring on female academics, as found in our research corresponds with prior literature [8,9,10,12,18,19,20]. Another factor, which ties in quite well with the issue of the impact of limited resource allocation in higher education institutions to the work of female academics, is the generalized assumption of policies and processes (including promotion and resource allocation decisions) being gender-neutral [62,63]. There is a large body of literature that has found that this is not the case. Our research findings correspond with prior literature in re-emphasizing that higher educational institutions are not gender-neutral organizations with objective processes [66]. Gendered influences in decisions and actions including resource allocations, assigning of duties and non-recognition of a large amount of work, which is typically assigned to female academics (for example teaching and administrative duties) act detrimental to the career progression of female academics. In addition, COVID-19 has increased pressure to perform according to the masculine expectations of winning grants and not only maintaining but improving scientific outputs and enhance productivity [73,74].

Time and financial resources limitations serve as barriers to achieving research output, which is required to secure research funding and so do inherent biases in the funding allocation process. For example, gender bias favors male applications (for grant funding) over female applications as male researchers are perceived as better-quality researchers and thus have higher research funding success rates [75,76]. In addition, there is reporting bias in critical research areas such as medical research, towards males, in methodologies, resulting in a generalization of results based on the study of one sex to both [77]. This is quite a severe implication concerning gendered research processes as there are remarkable physiological, psychological and behavioral differences between the two sexes. Majority of research cash for pandemic studies is being scooped up by male academics and women scientists voices are being dampened by the male rhetoric [78]. COVID-19 is further encouraging masculine work environments constituting of male models of regimes of uninterrupted labor and the ideal worker of an individual completely dedicated to work and not distracted by any other elements [78].

There are critical behavioral, organizational differences that have a more negatively pronounced impact on women academics than male academics [39]. Generally, regardless of administrative and teaching workloads, men have been found to focus more on research than women; they have been found to be more protective of their research time while women have been found to allocate more time to teaching, mentoring and service [39]. What women pursue holds less value for promotion purposes, especially when research is considered a priority for career advancement [39].

Differential impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on men and women in academia have been ascertained [73,79,80]. By undertaking a survey of 200 academics, researchers [80] found that COVID-19 related lockdowns have had a more pronounced negative impact on female academics due to a disproportionate increase in housework and childcare, compared to male academics. Scholars [73] undertook a global survey of academics from multiple disciplines and highlighted that although both men and women reported major increases in childcare (if relevant) and house hold burdens; women have been experiencing significantly more pronounced impact relating to decrease in time spent on research activities.

Some other scholars [80] analyzed more than 40,000 preprints, produced by more than 76,000 authors from 25 countries discovered an interesting occurrence. In United States, in the 10 weeks after lockdown, overall research productivity increased by 35%, nevertheless female academics’ productivity decreased by 13.9%, especially at top ranked institutions. Reduced research productivity in the COVID-19 pandemic environment for female academics has been confirmed too [55].

It appears that COVID-19 generated inequalities will continue and become more pronounced with time and will maintain a negative impact on women’s career advancement in multiple years to come [81]. We believe that this unfortunate impact is also due to COVID-19 generated reduction in internal research funding. Research funding has taken a massive hit due to drastic reduction in income from international students. Although gender differences in academic success have been long standing, systematic barriers have been exacerbated by the pandemic and these impacts will echo well into the future [81].

Author Contributions

Theory, T.K.; Research Methods, T.K.; Analysis, T.K.; Discussion, T.K. and P.S.; Conclusion, T.K. and P.S.; Revisions, T.K. and P.S.; Introduction, P.S.; Australian Context, P.S.; Literature Review, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially funded by Governance, Accountability and Law (GAL) Research Strategic Priority Area, College of Business and Law, RMIT University.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available in excel format if required. Please contact the authors directly.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Piyumee Siriwardhana for your paid contribution to data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Larkins, F.P. Australian Universities Gender Staffing Trends over the Decade 2008 to 2017; Melbourne University: Melbourne, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Public Sector Commission. Workforce Diversity-Women, Public Sector Commission, West Perth. Available online: https://publicsector.wa.gov.au/publications-resources/psc-publications/annual-reports/director-equal-opportunity-public-employment-annual-report-2012/workforce-diversity-women (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Gabster, B.P.; van Daalen, K.; Dhatt, R.; Barry, M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1968–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australia Universities. Higher Education: Facts and Figures; Universities Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector, Advice for Universities. Available online: https://www.genderequalitycommission.vic.gov.au/advice-universities (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Australian Government. Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012 Office of Parliamentary Counsel; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2016.

- Sage. What Is Sage. Available online: https://www.sciencegenderequity.org.au/about-sage/ (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Morrison, A.M.; Von Glinow, M.A. Women and minorities in management. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 1990, 45, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.S.V.; Thompson, J.R. Socializing women doctoral students: Minority and majority experiences. Rev. High. Educ. 1993, 16, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskin, L. Victimisation and agency: The social construction of union women’s leadership. Ind. Relat. J. 2006, 37, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkanlı, Ö.; White, K. Gender and leadership in Turkish and Australian universities. Equal Oppor. Int. 2009, 28, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skachkova, P. Academic careers of immigrant women professors in the US. High. Educ. 2007, 5, 697–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.E.B.; Cowin, L.S. The experience of marginalization in new nursing graduates. Nurs. Outlook 2004, 52, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Loessi, K.; Henderson, D. Changes in American society: The Context for Academic Couples. In Academic Couples; Ferber, M.A., Loeb, J., Eds.; University of Illinois Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1997; pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, J.T.; Adamson, R. Gender Differences in the Careers of Academic Scientists and Engineers: A Literature Review; National Science Foundation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2003; pp. 13–14.

- Nakhaie, M.R. Gender differences in publication among university professors in Canada. Can. Rev. Sociol. Anthropol. 2002, 392, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnert, G.; Holton, G. Who Succeeds in Science? The Gender Dimension; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.; Barrett, P. Women and academic workloads: Career slow lane or Cul-de-Sac? High. Educ. 2011, 61, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobele, A.R.; Rundle-Theile, S. Progression through academic ranks: A longitudinal examination of internal promotion drivers. High. Educ. Q. 2015, 69, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobele, A.R.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Kopanidis, F. The cracked glass ceiling: Equal work but unequal status. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education, Science and Training (DEST). Research Quality Framework: Assessing the Quality and Impact of Research in Australia. Department of Education Science and Training; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro, N.; Snead, S.L. “I’m not a real academic”: A career from industry to academe. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2013, 37, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.; Noonan, P.; Nugent, H.; Scales, B. Review of Australian Higher Education: Final Report; Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations: Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Parker, J. Comparing research and teaching in university promotion criteria. High. Educ. Q. 2008, 62, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisyte, L.; Hosch-Dayican, B. Changing academic roles and shifting gender inequalities: A case analysis of the influence of the teaching-research nexus on the academic career prospects of female academics in the Netherlands. J. Workplace Rights 2014, 17, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leišytė, L.; Hosch-Dayican, B. Gender and academic work at a Dutch university. In The Changing Role of Women in Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Eveline, J. Woman in the ivory tower: Gendering feminised and masculinised identities. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2005, 18, 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummell, B.; Devine, D.; Lynch, K. The care-less manager: Gender, care and new managerialism in higher education. Gend. Educ. 2009, 21, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, M. Behind the Scenes of Science: Gender Practices in the Recruitment and Selection of Professors in the Netherlands; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, M.; Śliwa, M. Gender, foreignness and academia: An intersectional analysis of the experiences of foreign women academics in UK business schools. Gend. Work Organ. 2014, 21, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, J.; Berg, E.; Chandler, J. Academic shape shifting: Gender, management and identities in Sweden and England. Organization 2006, 13, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bozeman, B. The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2005, 35, 673–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagilhole, B.; Goode, J. The contradiction of the myth of individual merit, and the reality of a patriarchal support system in academic careers: A feminist investigation. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2001, 8, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dever, M.; Morrison, Z. Women, research performance and work context. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2009, 15, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weert, E. The organised contradictions of teaching and research: Reshaping the academic profession. In The Changing Face of Academic Life; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 134–154. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, N. Factors affecting the career progress of academic accountants in Australia: Cross-institutional and gender perspectives. High. Educ. 2003, 46, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, E.A. How Do Career Strategies, Gender, and Work Environment Affect Faculty Productivity Levels in University-Based Science Centers? Rev. Policy Res. 2005, 22, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, Y.; Lillard, L. Output variability, academic labor contracts, and waiting times for promotion. Res. Labor Econ. 1982, 5, 157–188. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, J.; Lundquist, J.H.; Holmes, E.; Agiomavritis, S. The ivory ceiling of service work. Academe 2011, 97, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S. Women in science: The persistence of gender in Australia. High. Educ. Manag. Policy 2010, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.; Garwood, J. The heart of research is sick. Lab Times 2011, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sabzwari, S.; Kauser, S.; Khuwaja, A.K. Experiences, attitudes and barriers towards research amongst junior faculty of Pakistani medical universities. BMC Med. Educ. 2009, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakken, L.L.; Sheridan, J.; Carnes, M. Gender differences among physician–scientists in self-assessed abilities to perform clinical research. Acad. Med. 2003, 78, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocato, J.; Mavis, B. The research productivity of faculty in family medicine departments at US schools: A national study. Acad. Med. 2005, 80, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbezat, D.A. Gender differences in research patterns among PhD economists. J. Econ. Educ. 2006, 37, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suber, P. Removing the barriers to research: An introduction to open access for librarians. College Res. Libr. News 2003, 64, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, K.R.; Hapgood, K.P. The academic jungle: Ecosystem modelling reveals why women are driven out of research. Oikos 2012, 121, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, B. Narrative accounts of origins: A blind spot in the intersectional approach? Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2006, 13, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.M.; Fernandez-Mateo, I. Networks, race, and hiring. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royster, D.A. Race and the Invisible Hand: How White Networks Exclude Black Men from Blue-Collar Jobs; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger, N.H.; Mason, M.A.; Goulden, M. Stay in the game: Gender, family formation and alternative trajectories in the academic life course. Soc. Forces 2009, 87, 1591–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, G. How to survive and thrive in the mother-mentor marathon. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, M. COVID-19’s Gendered Impact on Academic Productivity. Available online: https://github.com/drfreder/pandemic-pubbias (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Shurchkov, O. Is COVID-19 Turning Back the Clock on Gender Equality in Academia? Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@olga.shurchkov/is-covid-19-turning-back-the-clock-on-gender-equality-in-academia-70c00d6b8ba1 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Amano-Patiño, N.; Faraglia, E.; Giannitsarou, C.; Hasna, Z. Who Is Doing New Research in the Time of COVID-19? Not the Female Economists. Vox EU. 2020. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/who-doing-new-research-time-covid-19-not-female-economists (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Myers, K.; Yang, W.; Yian Yin, T.; Cohodes, N.; Thursby, J.G.; Thursby, M.; Schiffer, P.; Walsh, J.; Lakhani, K.R.; Wang, D. Quantifying the Immediate Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Scientists. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.11358.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Bussey, K.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risman, B.J. Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender Soc. 2004, 18, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C.L. Framed before we know it: How gender shapes social relations. Gend. Soc. 2009, 23, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslanger, S. Gender and social construction. In Applied Ethics: A Multicultural Approach; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.W. Gender: A useful category of historical analysis. Am. Hist. Rev. 1986, 91, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. From sex roles to gendered institutions. Contemp. Sociol. 1992, 21, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J. Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gend. Soc. 1990, 4, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, D.M. The epistemology of the gendered organization. Gend. Soc. 2000, 14, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, E. Feminism: A fourth wave? Political Insight 2013, 4, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrye, H.K. The fourth wave of feminism: Psychoanalytic perspectives introductory remarks. Stud. Gender Sex. 2009, 10, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D. The fourth wave of feminism: Psychoanalytic perspectives. Stud. Gender Sex. 2009, 10, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.F. Gender, family characteristics, and publication productivity among scientists. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2005, 35, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, S. Gender, children and research productivity. Res. High. Educ. 2004, 45, 891–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley, P. Defining ‘early career’ in research. High. Educ. 2003, 45, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, C.; Hind, P. Occupational stress, burnout and job status in female academics. Gend. Work Organ. 1998, 5, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, T.; Shurchkov, O.; Stearns, J. Covid-19 disruptions disproportionately affect female academics. AEA Pap. Proc. 2021, 111, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muric, G.; Lerman, K.; Ferrara, E. Gender Disparity in the Authorship of Biomedical Research Publications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, 25379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, S. Research selectivity and female academics in UK universities: From gentleman’s club and barrack yard to smart macho? Gend. Educ. 2003, 15, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Lee, R.; Ellemers, N. Gender contributes to personal research funding success in The Netherlands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12349–12353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdcroft, A. Gender Bias in Research: How Does It Affect Evidence Based Medicine? J. R. Soc. Med. 2007, 100, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashencaen Crabtree, S.; Esteves, L.; Hemingway, A. A ‘new (ab) normal’? Scrutinising the work-life balance of academics under lockdown. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, T.M.; Eslen-Ziya, H. The differential impact of COVID-19 on the work conditions of women and men academics during the lockdown. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Ding, H.; Zhu, F. Gender inequality in research productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleschuk, M. Gender equity considerations for tenure and promotion during COVID-19. Can. Rev. Sociol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).