Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

- With regards to commitment and strategy, only two countries had no overarching cross-sectoral strategy, six countries did have one, but without a recent update. Most of these countries planned to revise their sustainable development strategies or development plans with the SDGs. Seventeen countries already had updated national strategies. In around half of all the Member States, these strategies appeared to be operational.

- Only a few countries linked their overarching strategy to the national budget. SDG budgeting is indeed an area where crucial progress could be made [19]. This is crucial because it would link the SDGs with the implementation power of ministries of finance and their instruments.

- Regarding leadership and horizontal coordination, 50% of the countries had visible coordination mechanisms with clear engagements across all departments, and had often moved SDG implementation leadership to the center of government.

- Stakeholder participation varied widely between Member States. In most countries, making SDG implementation processes inclusive was a priority, but in only eight countries, it was highly institutionalized and frequent. Still, it can be said that involving stakeholders in sustainable development processes, governance and strategic decision-making has become a somewhat mainstream norm across the EU Member States. Often, it is institutionalized and done on a regular basis. However, the study concluded that the fact that stakeholder consultation on strategic developments is not a baseline for all countries means that this this is a key area for improvement.

- Concerning monitoring and review, most countries had regular progress reports and had updated their indicator set with the SDGs. Only a few countries had defined, quantified, and time bound targets to achieve the SDGs nationally, and even fewer countries had put in place an independent, external review mechanism.

- Countries were the least advanced on the theme of knowledge and tools and institutions for the long-term. Only a few countries had put more than one tool in place to support the input of scientific knowledge through a science-policy interface and tools like sustainability impact assessments or sustainability checks for national budgets. Most countries had only created very limited versions of it. Institutions for the long-term were not a priority in most EU countries. In poorer countries, such as least developed countries and landlocked developing countries, the science-policy was generally structurally weak, which affects the ability to respond appropriately to both SDG and challenges presented by COVID-19 [20]. Elsewhere, the health diplomat Colglazier argues that “Catastrophic failures of the science-policy interface in many countries and globally have led to disastrous outcomes for public health, the economy, and international collaboration” [21].

- Finally, regarding activities of parliaments for the 2030 Agenda, there was approximately an equal number of countries that had so far only organized parliamentary debates on SDGs, and those that had one or two committees dealing with the Agenda 2030 or had created new institutional arrangements. It remains a challenge to include the SDGs in all core parliamentary functions: to scrutinize implementation of the SDGs nationally, to integrate them in legislation and in the budget.

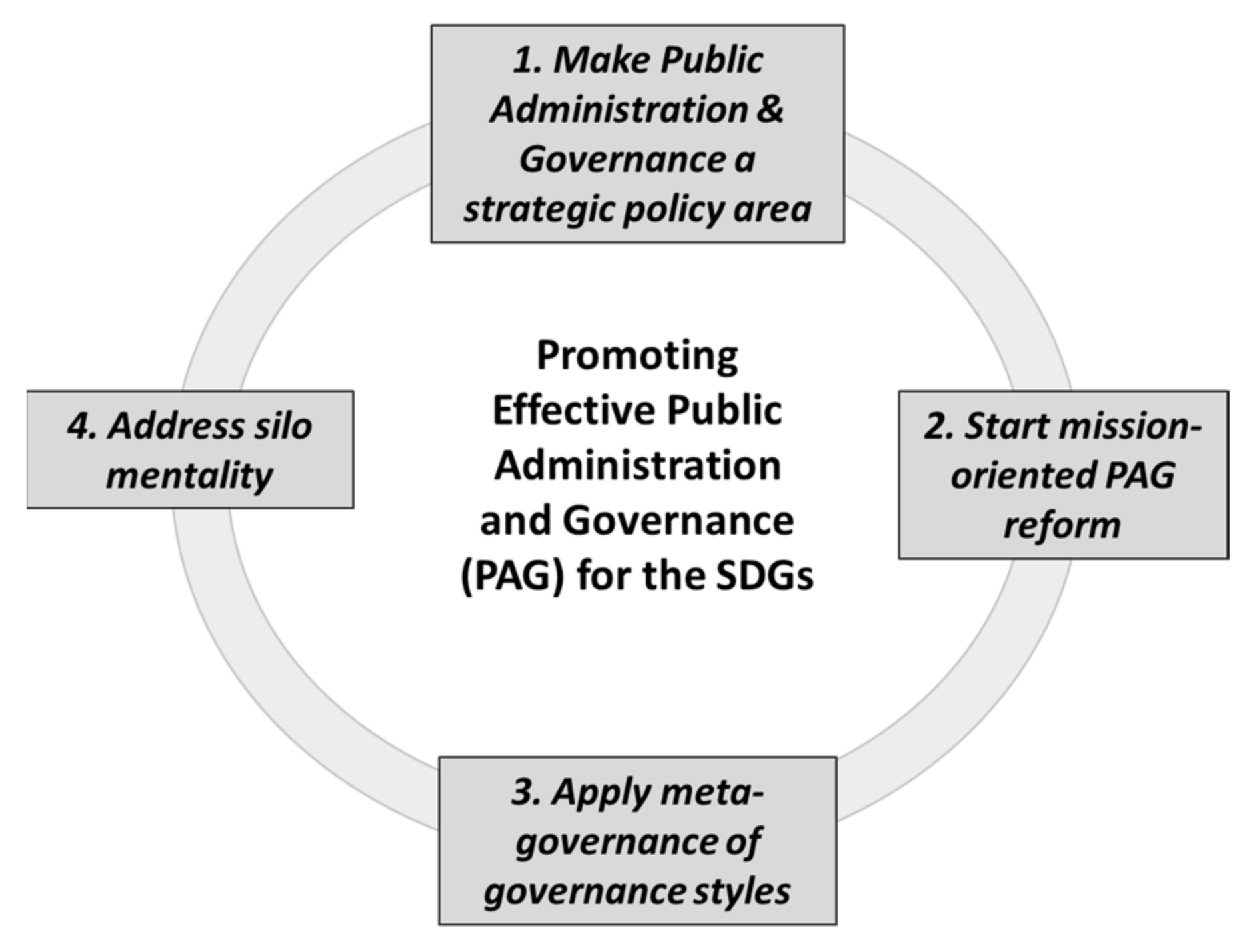

- Recognize that creating an effective public administration and governance (PAG) is an important strategic policy area;

- Begin with mission-oriented public administration and governance reform for SDG implementation, replacing the efficiency-driven public sector reform of the past decades;

- Apply culturally sensitive metagovernance to design, define and manage tackling trade-offs and achieving synergies between SDGs and their targets;

- Start concerted efforts to improve policy coherence with a mindset beyond political, institutional, and mental silos.

2. Public Administration and Governance as a Strategic Policy Area

2.1. Challenges

2.2. Key Elements

2.3. Recommendations on Position and Status of PAG

- Apply the guidance developed by the UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration in the form of 11 principles of effective governance for sustainable development, which were endorsed by the UN ECOSOC Council to do a SWOT analysis and develop a strategic policy to support the SDGs.

- Make Departments of ‘Administrative Affairs’ part of e.g., national inter-ministerial committees on the implementation of the SDGs. Only then can they develop adequate institutional mechanisms and ensure competences and skills of the work force directed to enable mainstreaming of the SDGs.

- Make the monitoring and progress assessment of SDGs 16 and 17 more focused on the quality of public institutions, policy coherence and partnerships; start using, for example, the new UN composite indicator for policy coherence (SDG 17.14.1).

- Ensure that all policy documents on the implementation of SDGs 1–15 contain a section on the required quality of public institutions and governance to ensure effective implementation.

3. Mission-Oriented Public Administration and Governance Reform

3.1. Challenges

3.2. Key Elements

3.3. Recommendations

- Test public sector reform programs before they start, on (a) the sensitivity for governance style interactions and metagovernance, (b) the appropriateness of the normative assumptions—which model or mixture, and (c) on having a sense of direction which should, at least, not be detrimental to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda, but which should preferably promote this [17]. Such a test could be integrated in ex ante impact assessments of reform programs—however, such programs do not require ex ante assessments in most countries, unlike policies, strategies and legislation in other areas.

- Implement concrete mechanisms for policy and institutional coherence for the SDGs, which should be inclusive, well-coordinated in e.g., national programs, based on a range of available approaches, supported by dedicated reforms, and accompanied by peer learning programs, training and networks of practitioners.

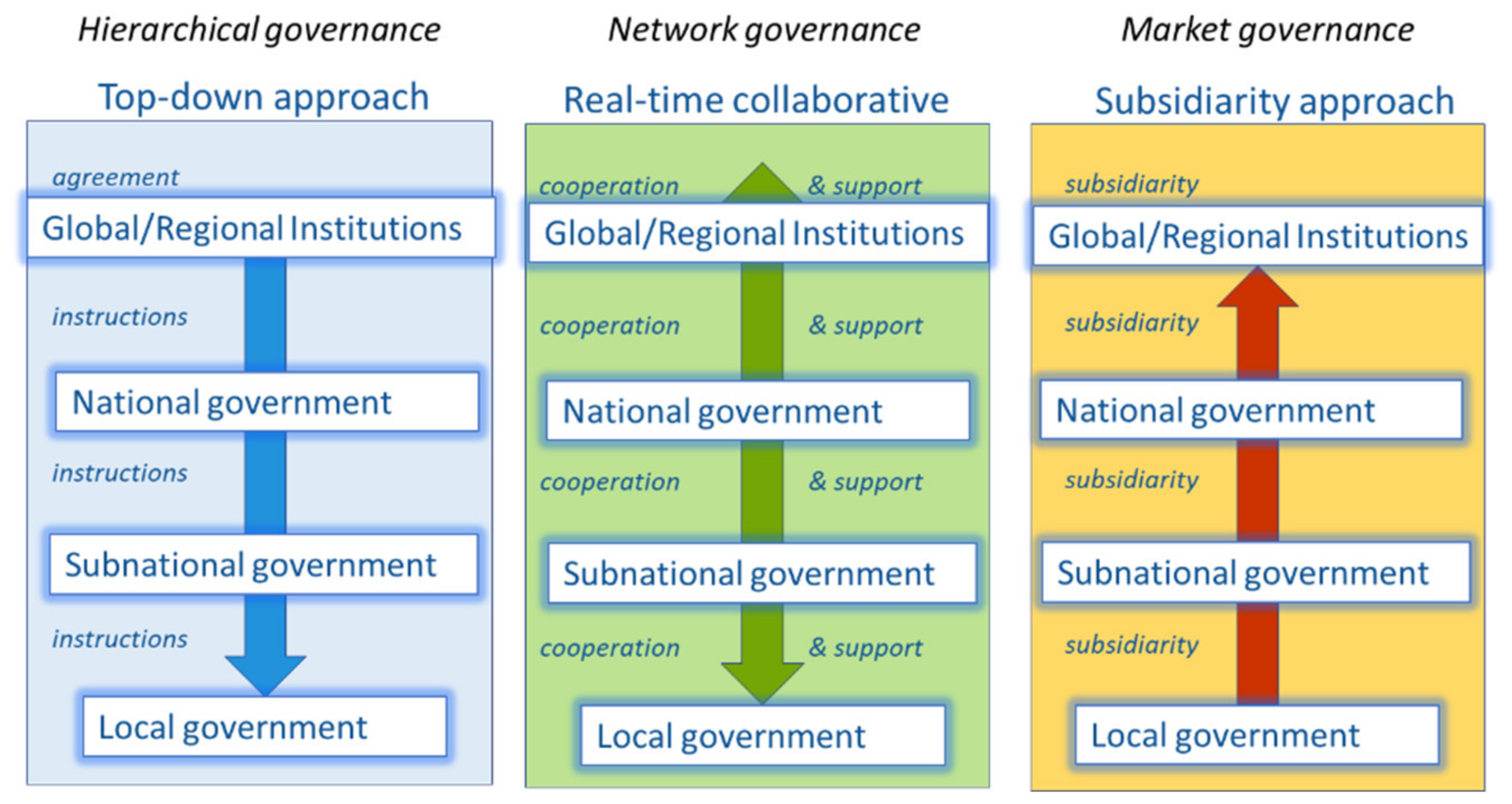

- Start pilots using ‘real-time collaborative multilevel governance’ for selected policy challenges which are both important and urgent.

4. Governance beyond Governance: Metagovernance to Tackle Trade-Offs and Benefit from Synergies

4.1. Challenges

4.2. Key Elements

- Framing of problems to make the solvable in an existing governance environment.

- Designing a framework by combining elements of different governance styles into compatible arrangements.

- Switching from one to another (main) governance style.

- Maintaining a chosen governance framework or arrangement, for example, protecting it against perverse/undermining influences in the governance environment.

4.3. Recommendations on Governance and Metagovernance for PAG Quality

- Make the understanding that governance styles are normative and metagovernance is a method to manage conflicts, failure and synergies, a starting point for improving administration and governance quality;

- Develop a contextual, flexible, and adaptive ‘metagovernance mindset’ fit for implementing the SDGs, to tackle trade-offs such as between change and stability;

- Integrate in PAG course programs for policymakers the relevant knowledge about the whole metagovernance toolbox—not only about the conventional governance style or style combination.

5. Mindsets, Policy Coherence, and ‘Dancing Silos’

5.1. Challenges

5.2. Key Elements

5.2.1. Negotiation Skills for Sustainability Challenges

5.2.2. Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development

5.2.3. Political, Institutional and Mental Silos

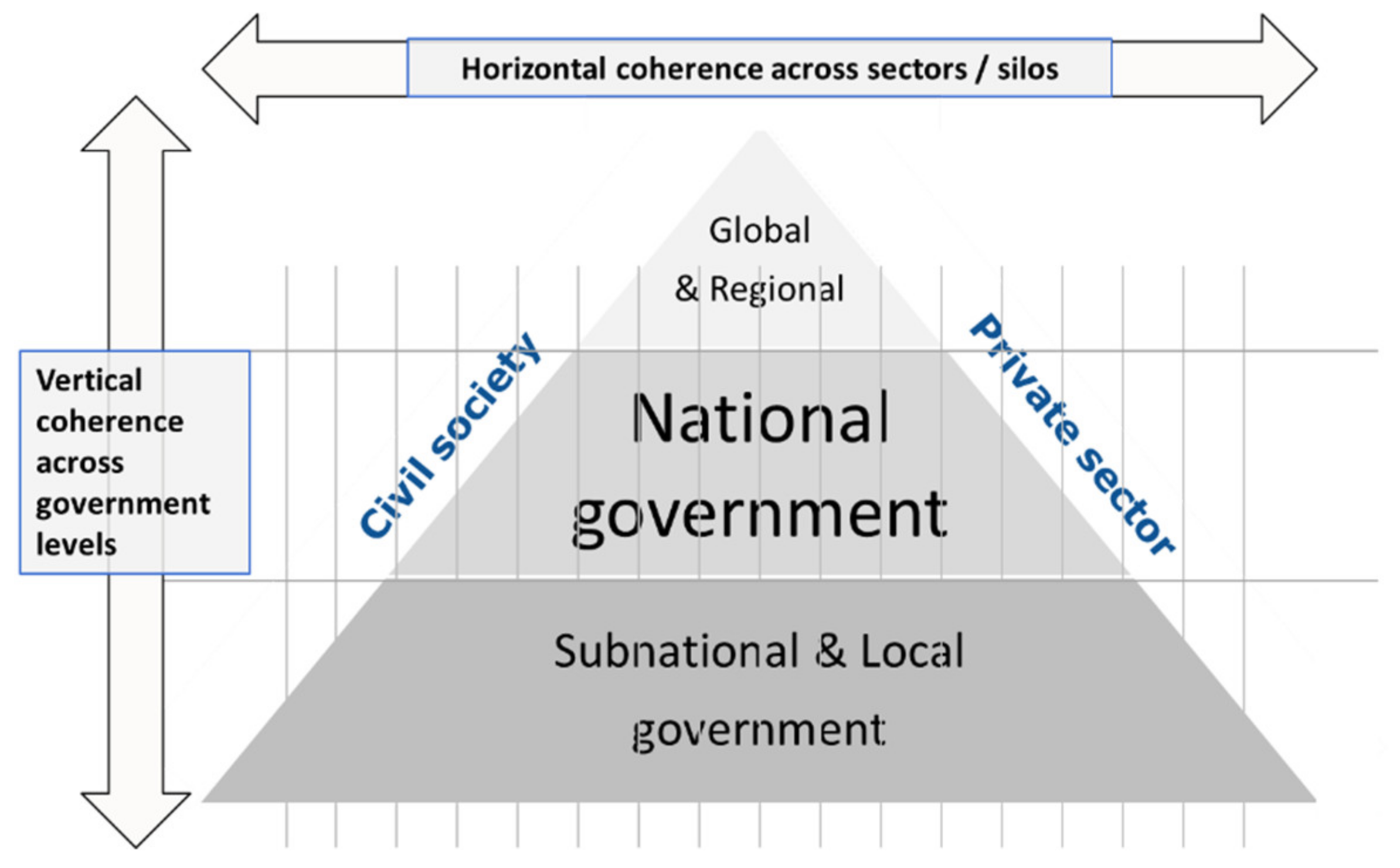

- Institutional silos: Most governmental organizations (and in fact most large organizations) work as classical bureaucracies. They organize their work by dividing complex problems into more simple, partial problems, which are dealt with by separate sectoral or functional bureaucratic entities, which we tend to call “silos.” Employees become a civil servant in one silo, and typically stay within it. Exceptions apply in administrations where civil servants rotate across silos, as this is beneficial for careers (e.g., England, European Commission). Such institutional silos give people the room to work undisturbed, but may effectively prevent them from working with others, both within government and with stakeholders. Because of the latter, the term silos generally has a negative connotation.

- Political silos: In democracies, politicians need to win majorities. This comes with different degrees of competition and power struggles. Individual politicians tend to focus on their file and defend it, to raise their own profiles. This can lead to political silos. As political silos are almost inherent to the democratic system, there are limits to tackling them, which also depends on the political culture of the country. Some have constitutional arrangements that reduce or eliminate the decision-making power of individual ministers (as in Sweden), or give a relatively strong (but still limited) “steering power” to the Prime Minister (as in Germany). In some countries, governments have experimented with so-called project ministers for cross-cutting issues that involve more than one Ministry (e.g., the Netherlands).

- Mental silos: In addition, and often related, there are mental silos; people have a firm belief that their problem definition and solution are not only the best, but even the only way forward. Different policy sectors like agriculture, transport and environment have their own world view and tend to operate in isolation. There are cultural, political, power-and career- related, cognitive and other reasons why people have ‘tunnel views’ and argue against change. However, for the comprehensive SDGs, for moving toward sustainable development with a need for policy integration and coherence, we need to step out of our comfort zones.

- Institutional silos represent positive features of government organizations such as clear lines of command, responsibility, focus on a given target and having internal “hotspots,” where expertise, memory and learning are concentrated. With respect to the SDGs, an accountable “silo” is needed in each country for, inter alia, reporting progress at the national level.

- They have a different function and meaning in different administrative cultures. In Rechtsstaat cultures like Germany, and hierarchical ones in general, opening up silos has turned out to be more difficult than in consensus cultures like the Netherlands and Denmark, or in public interest models of government like in Australia, New Zealand and the UK [23]). Hence, a closer look is required into how they operate, and a general verdict that silos are bad is culturally insensitive.

- They provide clear, reliable, and stable contact points within a Ministry for partners and stakeholders. Without them, it can be difficult to develop enough trust that is needed to make a network approach work. Partnerships and participation increase the challenge of coordination, and thus require clear anchor points. Hence, the common assumption that silos prevent stakeholder participation is questionable.

5.3. Recommendations on Mindsets and Dealing with Silos

- Increase the awareness of existing PAG mindsets and their strengths and weaknesses;

- Consider offering a Mutual Gains Approach training for all policy officers and their managers;

- Integrate informal cross-silo working in basic training programs for civil servants, for example combined in a package with communication and collaboration tools.

6. Conclusions

- How do the strategic tasks and position of the national department responsible for the quality of public administration and governance relate to the overall quality of public administration and governance in a country, and how does this relate to the culturally preferred main governance style(s) in that country?

- Mission-oriented reform makes the ‘ends’ central and leaves the ‘means’ open. But does the end justify any means? Research to help deciding about an appropriate balance in specific cases would be useful.

- Although there is a rich and growing academic literature concerning metagovernance, it seems that there is a need for more empirical research on the application of metagovernance as a design and management approach for (sustainability) policies. The fact that metagovernance is a heuristic concept—the practice was there before the theory—should lead us to assume that there is ample empirical material for such research.

- Research would be welcome on conditions that influence the success of collaboration across ‘silos’, and how such conditions vary with different (administrative) cultures and traditions.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meuleman, L. It Takes More than Markets: First Lessons from the Covid-19 Pandemic for Climate Governance. ECA J. 2020, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M. The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1-61039-675-8. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Protecting People and Economies: Integrated Policy Responses to Covid-19; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Supporting Public Administration in EU Member States to Deliver Reforms and Prepare for the Future; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Cultural diversity and sustainability metagovernance. In Transgovernance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 37–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 5, ISBN 0-8039-1306-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, S.; Bouckaert, G.; Galli, D.; Reiter, R.; Hecke, S.V. Opportunity Management of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Testing the Crisis from a Global Perspective. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, D. Risks and Opportunities in Responding to the Coronavirus Crisis|Corona Sustainability Compass. Available online: https://www.csc-blog.org/en/risks-and-opportunities-responding-coronavirus-crisis (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Cohen, M.D.; March, J.G.; Olsen, J.P. A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegele, Y.; Schnabel, J. Federalism and the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis: Centralisation, Decentralisation and (Non-) Coordination. West Eur. Polit. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattke, F.; Martin, H. Collective Action during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Case of Germany’s Fragmented Authority. Adm. Theory Prax. 2020, 42, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhl, S.; Lehrer, R.; Blom, A.G.; Wenz, A.; Rettig, T.; Krieger, U.; Fikel, M.; Cornesse, C.; Naumann, E.; Möhring, K. Preferences for Centralized Decision-Making in Times of Crisis: The COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. 2021. Available online: http://www.ronilehrer.com/docs/JHET.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- UNDESA. Summary by the President of the Economic and Social Council of the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development Convened under the Auspices of the Council at Its 2020 Session; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Planet’s on ‘Red Alert’ UN Chief Warns Leaders at President Biden’s Climate Summit. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/04/1090382 (accessed on 13 May 2021).

- The European Green Deal. In COM (2019) 640 Final—Communication; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 Establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Meuleman, L. Metagovernance for Sustainability: A Framework for Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018; ISBN 1-351-25058-2. [Google Scholar]

- Niestroy, I.; Hege, E.; Dirth, E.; Zondervan, R.; Derr, K. Europe’s Approach to Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: Good Practices and the Way Forward; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hege, E.; Brimont, L.; Pagnon, F. Sustainable Development Goals and Indicators: Can They be Tools to Make National Budgets More Sustainable? Public Sect. Econ. 2019, 43, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrl, R.A.; Liu, W.; Mukherjee, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A Wake-up Call for Better Cooperation at the Science–Policy–Society Interface. In UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) Policy Briefs; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 62. [Google Scholar]

- Colglazier, E.W. Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Catastrophic Failures of the Science-Policy Interface. Sci. Dipl. 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Niestroy, I. Managing the Implementation of the SDGs. In Thematic Study No.9, European Public Administration Country Knowledge 3; EC: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2021; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, C.; Bouckaert, G. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis of NPM, the Neo-Weberian State, and New Public Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNCEPA. Principles of Effective Governance for Sustainable Development; UNCEPA: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- APRM. Baseline Study on CEPA Principles for Effective Implementation of SDGs & Agenda 2063; APRM: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021; forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Feiock, R.C.; Scholz, J.T. Self-Organizing Federalism: Collaborative Mechanisms to Mitigate Institutional Collective Action Dilemmas; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 1-139-48274-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, J. Innovation in Governance and Public Services: Past and Present. Public Money Manag. 2005, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Toolbox Quality of Public Administration; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Steering, Rowing, Drifting, or Sinking? Changing Patterns of Governance. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. Transgovernance: Advancing Sustainability Governance; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 3-642-28009-9. [Google Scholar]

- Head, B.W. Toward More “Evidence-informed” Policy Making? Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Better Regulation for Better Results—An EU Agenda; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Why We Need ‘Real-time’ Multi-level Governance for the SDGs. In Guest Article IISD SDG Knowledge Hub, 16 April 2019; IISD: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, F.; Kern, F.; Borgström, S.; Gorissen, L.; Steffen, M.; Egermann, M. Urban Sustainability Transitions in a Context of Multi-Level Governance: A Comparison of Four European States. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 26, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.H.; Laws, N.; Renz, I.; Hacke, U.; Wesche, J.; Friedrichsen, N.; Peters, A.; Niederste-Hollenberg, J. Anwendung Der Mehr-Ebenen-Perspektive Auf Transitionen: Initiativen in Den Kommunal Geprägten Handlungsfeldern Energie, Wasser, Bauen & Wohnen; Working Paper Sustainability and Innovation, Fraunhofer ISI: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2017; Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/150041/1/880193638.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Rittel, H.W.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A leader’s framework for decision making. In Harvard Business Review; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Technical Support for Implementing the European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A.; Aitken, K. Public Sector Innovation System Scan of Latvia. In OPSI Blog OECD; OPSI: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft, J. Sustainable Development. In The Sage Handbook of Governance; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Sustainability Transitions: Policy and Practice; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Public Management and the Metagovernance of Hierarchies, Networks and Markets: The Feasibility of Designing and Managing Governance Style Combinations; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 3-7908-2054-7. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Governance Frameworks; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 885–901. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. The UN Wants Accelerated Governance of the Sustainable Development Goals—But are We Really Ready? Keynote IIAS Governance Week, 5 February 2020. In Metagovernance for Sustainability; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.; Ellis, R.; Wildavsky, A. Cultural Theory; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Raver, J.L.; Nishii, L.; Leslie, L.M.; Lun, J.; Lim, B.C.; Duan, L.; Almaliach, A.; Ang, S.; Arnadottir, J. Differences between Tight and Loose Cultures: A 33-Nation Study. Science 2011, 332, 1100–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M. Rule Makers, Rule Breakers: Tight and Loose Cultures and the Secret Signals That Direct Our Lives; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 1-5011-5294-7. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. The Governance of Complexity and the Complexity of Governance: Preliminary Remarks on Some Problems and Limits of Economic Guidance; Lancaster University: Bailrigg, UK, 1997; pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, J. Governing as Governance; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 0-7619-4036-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dunsire, A. Manipulating Social Tensions: Collibration as an Alternative Mode of Government Intervention. MPIfG Discuss. Pap. 1993, 7, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Riaz, Z.; Ray, S.; Ray, P.K. Collibration as an Alternative Regulatory Mechanism to Govern the Disclosure of Director and Executive Remuneration in Australia. Int. J. Corp. Gov. 2015, 6, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. The Pegasus Principle Reinventing a Credible Public Sector; Lemma: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.H.; Hengesbaugh, M.; Onoda, S. Governing the Sustainable Development Goals in the COVID-19 Era: Bringing Back Hierarchic Styles of Governance? Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, M.B.; do Rosário Partidário, M.; Meuleman, L. A Comparative Analysis on How Different Governance Contexts May Influence Strategic Environmental Assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 72, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, J.R.; Gbikpi, B. Participation and Metagovernance: The White Paper of the EU Commission. In Participatory Governance; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Cini, M. The Limits of Inter-Institutional Co-Operation: Defining (Common) Rules of Conduct for EU Officials, Office-Holders and Legislators. In Proceedings of the Jean Monnet Multi-lateral Research Group on Decision-Making before and after Lisbon (DEUBAL), Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 3–4 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Porras-Gómez, A.-M. Metagovernance and Control of Multi-Level Governance Frameworks: The Case of the EU Structural Funds Financial Execution. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2014, 24, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes, A.; Maas, W. Sixty-Five Years of European Governance. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 2016, 12, 395–405. [Google Scholar]

- Tömmel, I. EU Governance of Governance: Political Steering in a Non-Hierarchical Multilevel System. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 2016, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. From governance to governance failure and from multi-level governance to multi-scalar meta-governance. In The Disoriented State: Shifts in Governmentality, Territoriality and Governance; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli, C.M. The Open Method of Coordination: A New Governance Architecture for the European Union? Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003; ISBN 91-85129-00-3. [Google Scholar]

- Héritier, A. New Modes of Governance in Europe: Increasing Political Capacity and Policy Effectiveness. State Eur. Union 2003, 6, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Aukes, E.J.; Matamoros, G.O.; Kuhlmann, S. Meta-Governance for Science Diplomacy-towards a European Framework; Universiteit Twente—Department of Science, Technology and Policy Studies (STePS): Enschede, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hesse, J.J.; Hood, C.; Peters, B.G. Paradoxes in Public Sector Reform: Soft Theory and Hard Case; Duncker & Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L.; Lawrence Susskind, S.; Field, P. Dealing with an Angry Public: The Mutual Gains Approach to Resolving Disputes; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 0-684-82302-0. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development 2019: Empowering People and Ensuring Inclusiveness and Equality|En|OECD. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/gov/policy-coherence-for-sustainable-development-2019-a90f851f-en.htm (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Meuleman, L. Promoting Policy and Institutional Coherence for the Sustainable Development Goals. In Proceedings of the 17th Session of the UN Committee of Experts on Public Administration, New York, NY, USA, 23–27 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, R.A.; Hannibal, B.; Portney, K. The Role of Communication in Managing Complex Water–Energy–Food Governance Systems. Water 2020, 12, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L. It is about time to promote policy and institutional coherence for the SDGs. In Guest Article IISD SDG Knowledge Hub, 17 April 2018; IISD: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- TAIEX—Environmental Implementation Review—PEER 2 PEER—Environment—European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/eir/p2p/index_en.htm (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Methodology for SDG-Indicator 17.14.1: Mechanisms in Place to Enhance Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020.

- Bento, F.; Tagliabue, M.; Lorenzo, F. Organizational Silos: A Scoping Review Informed by a Behavioral Perspective on Systems and Networks. Societies 2020, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahenzli, M. Carrot or Stick: Overcoming Silos in Enterprise Architectures. In Proceedings of the 15th Internationalen Tagung Wirtschaftsinformatik, Potsdam, Germany, 9–11 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Niestroy, I.; Meuleman, L. Teaching Silos to Dance: A Condition to Implement the SDGs. In Guest Article IISD SDG Knowledge Hub; IISD: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L. Gaps and Challenges in Promoting Cross-Ministerial Collaboration. In Presentation at UNDESA Online Training Course on “Changing Mindsets and Strengthening Governance Capacities for Policy Coherence in the Arab Region”; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992; Volume 17, ISBN 0-8039-8346-8. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, Å.; Weitz, N.; Nilsson, M. Follow-up and Review of the Sustainable Development Goals: Alignment vs. Internalization. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belasco, J.A. Teaching the Elephant to Dance: The Manager’s Guide to Empowering Change; Plume: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 0-452-26629-7. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Better Regulation—Joining Forces to Make Better Laws; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Principles | |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness | 1. Competence |

| 2. Sound Policymaking | |

| 3. Collaboration | |

| Accountability | 4. Integrity |

| 5. Transparency | |

| 6. Independent oversight | |

| Inclusiveness | 7. Leaving no one behind |

| 8. Non-discrimination | |

| 9. Participation | |

| 10. Subsidiarity | |

| 11. Intergenerational equity | |

| Governance Style | Example of Typical Features of the Styles |

|---|---|

| Hierarchical governance | Rationality, reliability, stability, legitimacy, justice, accountability, risk averse, government-centred, centralized, planning and design, authoritative, instructions, one-way communication, dependency, subordinates, obedience, rules-based, command and control |

| Network governance | Partnerships, collaborative learning, co-creation for innovation, informal arrangements, trust-based, harmony, communication as dialogue, process management, diplomacy, mutual dependence, mutual gains approach, consensus, voluntary agreements, covenants |

| Market governance | Rationality, cost-driven, flexible, competition as driver for innovation, price, marketing, decentralized, bottom-up, individualist, autonomy, self-determination, empowering, services, contracts, incentives, awards and other market-based instruments |

| 1. Ways of life. | 11. Strategy styles | 21. Control mechanism | 31. Accountability styles | 41. Values of civil servants |

| 2. Relational values | 12. Reply to resistance | 22. Coordination mechanism | 32. Context | 42. Key competences of civil servants |

| 3. Theor. background | 13. Organiz. orientation | 23. Transaction types | 33. Process and project management | 43. Objectives of management development |

| 4. Key concepts | 14. Actor perceptions | 24. Degree of flexibility | 34. Public sector reform approaches | 44. Dealing with power |

| 5. Mode of calculation | 15. Selection of actors | 25. Level of commitment | 35. Innovation | 45. Conflict resolution types |

| 6. Primary virtues | 16. Stocktaking of actors | 26. Communication styles | 36. Relation types | 46. Suitability for problem types |

| 7. Common motive | 17. Institutional logic | 27. Roles of knowledge | 37. Societal interactions | 47. Reframing |

| 8. Motive of actors | 18. Dealing with organizational silos | 28. Science-policy interface | 38. Roles of public managers | 48. Typical governance failures |

| 9. Roles of government | 19. Policy instruments | 29. Impact assessments | 39. Leadership styles | 49. Role of public procurement |

| 10. Metaphors | 20. Decision making unit | 30. Access to information | 40. Degree of empowerment inside organizations | 50. Typical output and outcome |

| What Is Bad? | What Is Good? | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Political silos (macro level) | Competition between political leaders/ ministers Legal right/duty of ministers to be the sole responsible | Political silos reflect the different values of political parties in a democratic system |

| 2. Institutional/ organisational silos (meso level) | Lack of trust between the silos Contacts/communication between silos may be prohibited or must go via hierarchy | Institutional silos provide structure, focus, protection against other departments; clarity, responsibility, transparency, accountability |

| 3. Mental silos (micro level) | Lack of: common goals, joint responsibility, interest in other colleagues Not taking responsibility be- yond the own job description Let ‘monkey’ (task) jump from your shoulder to another | Mental silos provide identification (‘this is who we are’); a ‘safe’ work environment, a ‘home base’ protected from external interventions |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meuleman, L. Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115914

Meuleman L. Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115914

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeuleman, Louis. 2021. "Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115914

APA StyleMeuleman, L. (2021). Public Administration and Governance for the SDGs: Navigating between Change and Stability. Sustainability, 13(11), 5914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115914