Protection of Children in Difficulty in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Document analysis. Document analysis was conducted on policies issued at the national and local levels on protecting and caring for children during the pandemic; the work report on services for children in difficulty during the pandemic in Shanghai and Guangzhou; media reports on the protection of children in difficulty; and the minutes of a seminar held in Shanghai on the protection of children with COVID-19.

- In-depth interview method. Thirteen in-depth interviews were conducted with relevant government staff engaged in child welfare work, child social workers, social workers working with children in difficulty, child welfare directors, child welfare supervisors, and medical and social workers in children’s hospitals (see Table 1 for the list of interviewees). The thirteen interviewees were chosen because of their involvement with the Shanghai children’s protection program “Love Around Children”, which is discussed later in this article. The program comprises multiple areas in child protection policy implementation. Due to the pandemic, seven of the thirteen interviews were conducted online, the rest were one-on-one interviews. The interviews were conducted in accordance with the semi-structured interview outline prepared in advance. All interviewees were informed of the purpose of the interview and their consent was obtained before the interview. The main contents of the semi-structured interview included the problems that were to be solved through the policy; the path and guarantee mechanism of policy implementation; difficulties in implementing the policy; the interviewees thoughts on feasible solutions.

- Case analysis. In-depth case analysis was conducted on 14 cases collected in Shanghai involving 16 children in difficulty—eight boys and eight girls with an average age of nine-and-a-half years (see Table 2 for the list of cases). Among the 14 cases, 12 are typical cases of child protection in Shanghai, and services from the government are being received during the pandemic. The other two cases were provided by medical social workers in the children’s hospital; these two children are migrant children who do not have Shanghai “Hukou” (koseki) and were not covered by the local government program. The main content of case coding analysis included the main problems faced by the children; who is helping them; the main resources to help them; the children’s problems that have been solved; and reasons why problems have not been solved.

3. Results

3.1. Government Response

3.1.1. Protecting Children without or Lacking Proper Guardianship

- (1)

- In terms of the report on the identification of qualified children, in addition to the responsibilities of child welfare director (also be called barefoot social worker) and child welfare supervisor in the township/sub-district and village/neighborhood committees, the notice clarifies the reporting obligations of medical workers providing on-site services, teachers, community workers, social workers, volunteers, and relevant charitable organizations. The notice also emphasizes the discovery, reporting, and referral role of the women’s rights protection service hotline.

- (2)

- There are four provisions for further implementation of custody and care responsibilities. First, the notice clarifies that, if a child’s parents or other guardians cannot fully perform the duty of raising in custody due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the village/neighborhood committee shall urge them to entrust other persons with guardianship capabilities to take care of the child on their behalf. Second, if there is no legally qualified guardian, the village/neighborhood committee shall be responsible for temporary care. Third, where there are actual difficulties, the county-level civil affairs department shall assume temporary custody. Lastly, for children whose care is entrusted to a dedicated person, a child protection supervisor/chief, executive committee member of a grassroots women’s federation, or community/social worker shall be designated to take all-round responsibilities, paying home visits or conducting telephone follow-ups at least twice a week to track the condition of custody.

- (3)

- The notice clarifies that rescue and assistance shall be provided to children and families in difficulty due to the impact of the pandemic. Temporary assistance shall be provided in a timely manner in accordance with relevant laws and regulations. Medical institutions shall have a green channel in place for treating children. The government shall support social workers and other professionals in providing psychological counseling, spiritual care, and family companionship services for children of different ages. Rescue and protection agencies for minors shall actively participate in the fast response, temporary care, service referral, case tracking, resource sharing, and other services for children without guardians.

- (4)

- The rescue and protection of children lacking custody shall be strengthened through various measures, including assigning the leading role to civil affairs departments at all levels, women’s federations, and women’s and children’s working committee offices, ensuring adequate financial support, increasing government procurement of services, and strengthening supervision.

3.1.2. Protecting Child Welfare Institutions, Special Child Groups, and Families Affected by COVID-19

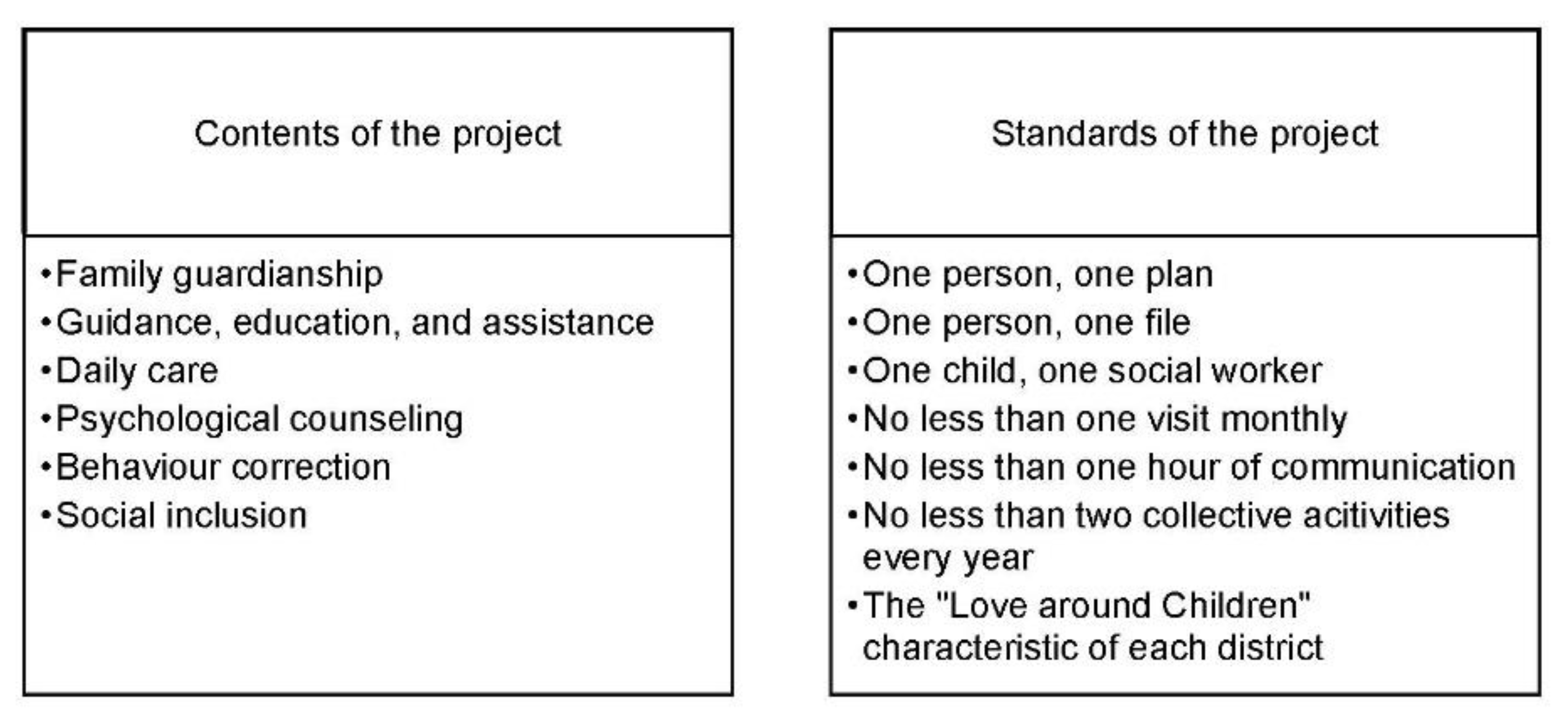

3.2. Cooperation between the Government and Non-Governmental Social Service Organizations

3.3. The Pandemic’s Revelation of the Need for Development

- (i)

- The legislation of child protection has a long way to go.

“In fact, we found out that these two children were victims of domestic violence and severe neglect and were still at great risk after discharge. We knew there was a mandatory reporting system, but we didn’t report it to the police. Based on our past experience, it’s useless to report. Some of the children’s household registrations are in other jurisdictions, and the police are even reluctant to treat them, saying that they are not in charge of them, and let us find the police of the child’s local registration base instead.”(Medical social worker at a children’s hospital; Cases 1 and 2)

“When we intervened, we found the mother very difficult to convince and wild, threatening that if we call the police once, she would beat the child up once. However, we had no choice but to report it to the police. When the police came, it was only a reprimand and nothing more substantial was done.”(Children’s social worker of the Children’s Agency; Case 6)

“When the father beat the child, the grandma could not stop it and called the police. But when the police came, the grandma refused to allow the police to take the child for an injury test for fear that they would arrest her son. It is difficult to reconcile love and law, and it was left unattended.”(Child protection chief; Case3)

- (ii)

- The establishment of child protection system needs to be further improved and institutionalized.

“When a document was issued, I really wanted to give some impetus. But without follow-up support, how long this work can last is really uncertain. We want to push it forward, but we find that we are often ‘stuck’ in many places and can’t move.”(Children’s social worker at WFWP)

“At present, this project is promoted by the civil affairs departments, mainly like a ‘safety net.’ The targeted service groups are strictly limited. The service to children in difficulty mainly concentrates upon hardship allowance. Children who do not have household registration in this city are not in the scope of services. In addition to hardship allowance, some other needs of children and families are still very difficult to meet.”(Social worker of a social organization)

“Children Rescue and Protection Center? We do have that, and the facilities are ready, but it’s just a center in name only, and it hasn’t been activated once. The center’s staff members are also part-time staff from welfare institutions. I know there should be professional social workers, I know, but...”(Child protection supervisor)

“Although I am a child protection chief, my main job is civil affairs in the community. I really want to help these children, but I often don’t have the energy to do so. Sorry, there are too many things to do.”(Child protection chief)

“At present, almost all child protection chiefs in rural areas are part-time and there is no subsidy. Only some projects funded by foundations will have a small subsidy. So, doing it has a lot to do with people, and people who are capable and caring will do more.”(Deputy Secretary General of District Social Workers Association)

- (iii)

- There is an urgent need to expand the pool of professional children’s social workers.

“Sometimes, I don’t really know how to do it. There is training, but only two-day intensive training per year. It helps, but it really doesn’t help much.”(Child welfare director)

“I’m a children’s social worker. But when I was at school, there was no specific course on children’s social work. I just learned while doing it, and it was quite confusing at times.”(Children’s social worker)

“Our organization didn’t do children’s social work before. During the outbreak, the government bought our project. I don’t have the knowledge and experience of working with children. I want to learn, but I can’t find good learning materials and courses. For the whole of China, child protection has developed rapidly in recent years, but we are obviously not ready yet...”(Social worker of a Children in Difficulty Protection Project)

- (iv)

- Research and exploration are needed to strengthen child protection in the post-pandemic era.

“Since the outbreak, more than 20 children suspected of suicide have been treated in our hospital, 12 of whom committed suicide with pills and 8 jumped from buildings. Compared with the same period of the previous year, the data is obviously high. I don’t know what happened.”(Medical social worker at a children’s hospital)

“During the epidemic, we have encountered a lot of confusion or problems in the process of moving forward, and we hope that experts, including practitioners, will join us to crack and study them.”(Children’s work officer with the government)

“I hope that after the epidemic, or from the present moment, our policies will include the needs of every child and that our professional services will be delivered to those most marginalized... Next time, I hope that we don’t start out as overwhelmed as we were this time.”(Social worker of a Children in Difficulty Protection Project)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, Y.; Mo, X.; Qi, X.; Jiang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Tong, S. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among Children in China. Pediatrics 2020, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, F.; Plancq, M.-C.; Tourneux, P.; Gouron, R.; Klein, C. Was child abuse inderdetected during the COVID-19 lockdown? Arch. Pédiatrie 2020, 27, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J. Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanesi, L.; Marchetti, D.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verroccio, M.C. The Effect of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Parents: A Call to Adopt Urgent Measures. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pr. Policy 2020, 12, S79–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fay, J.; Levinson, M.; Stevens, A.; Brighouse, H.; Geron, T. Schools During the COVID.19 Pandemic: Sites and Sources of Community Resilience. COVID-19 Rapid Response Impact Initiative. In COVID-19 White Paper 20; Edmond, J., Ed.; Safra Center for Ethics; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 11 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rundle, A.G.; Park, Y.; Herbstman, J.B.; Kinsey, E.W.; Wang, Y.C. COVID-19-Related School Closing and Risk of Weight Gain among Children. Obesity 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priolo Filho, S.R.; Goldfarb, D.; Zibetti, M.R.; Aznar-Blefari, C. Brazilian Child Protection Professionals’ Resilient Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice of Carrying Out the Pilot Work of Building a Moderately Inclusive Child Welfare System. Minhan No. 206. 2013. Available online: http://www.china.com.cn/guoqing/zwxx/2013-07/03/content_29309610.htm (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice on Launching the Second Batch of National Pilot Work for Social Protection of Minors. Minhan No. 240. 2014. Available online: http://smzt.gd.gov.cn/attachements/2019/01/05/a0f1f86213753c366acb7a387cfb2b5b.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. The Guideline for Reinforcing Support for Children in Need Issued by the State Council. Guofa No. 36. 2016. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2016-06/16/content_5082800.htm (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- China Philanthropy Research Institute. A Ten-Year Review and Prospect of China’s Child Welfare and Protection Policy. Available online: http://www.bnu1.org/show_1916.html (accessed on 29 May 2020).

- Kevat, A. Children may be less affected than adults by novel coronavirus (COVID-19). J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 56, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, B.N.; Mccall, R.B.; Groark, C.J.; Muhamedrahimov, R.J.; Palmov, O.I.; Nikiforova, N.V. Caregiver sensitivity and consistency and children’s prior family experience as contexts for early development within institutions. Infant Ment. Health J. 2018, 39, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.J.; Barrientos, R.M. The impact of nutrition on COVID-19sceptibility and long-term consequences. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covid, T.C.; Stephanie, B.; Virginia, B.; Nancy, C.; Aaron, C.; Ryan, G.; Matthew, R. Geographic Differences in COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Incidence—United States, 12 February–7 April 2020. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll-Dayton, B.; Punpuing, S.; Tangchonlatip, K.; Yakas, L. Pathways to grandparents’ provision of care in skipped-generation households in Thailand. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 1429–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.; Lachman, J.M.; Sherr, L.; Wessels, I.; Krug, E.; Rakotomalala, S.; Butchart, A. Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.L. Some Reflections and Suggestions on the Juveniles Influenced by COVID-19. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=FZWT202001001&DbName=CJFQ2020 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Schwartz, J.; Yen, M.Y. Toward a collaborative model of pandemic preparedness and response: Taiwan’s changing approach to pandemics. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2017, 50, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilke, N.G.; Howard, A.H.; Pop, D. Data-informed recommendations for services providers working with vulnerable children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijing Youth Daily-YNET. A Local Joint Investigation Team Was Established after the Death of a 17-Year-Old Cerebral Palsy Teenager Boy in Huangguang Who Died Six Days after His Father Was Quarantined. Available online: http://news.ynet.com/2020/01/30/2351377t70.html?from=groupmessage (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- The Elderly in Shiyan, Hubei Province Died at Home, Leaving behind the 6-Year-Old Grandson. The Story of Left-Behind Children during the Epidemic is Heartbreaking. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/376075361_120582926 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Because of no Phone Available for Online Courses, a Girl Committed Suicide? Her father: The School Will Have an Exam on the Day of the Accident. Netease News. Available online: http://news.163.com/20/0302/00/F6M3V2AQ00019B3E.html (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice on the Care and Protection for Children Left Unattended after the Virus Outbreak. Mindian No. 19. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=14150&mtype= (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. A Circular of Proposing Measures to Care for, Protect and Aid Children Left Unattended after the Virus Outbreak Issued by the State Council’s Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism for the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Epidemic. Guofamingdian No. 11. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-03/15/content_5491581.htm (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. The Circular of Urging Prevention and Control of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Civil Service Institutions Released by the State Council. Guofamingdian No. 6. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2020-02/28/content_5484533.htm (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the Poverty Relief Office of the State Council on the Action Plan of Social Assistance for the Needy. Minfa No. 18. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=13759&mtype= (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The notice of the Ministry of Civil Affairs on the Organization of “Policy Preaching into Villages (Communities)” Activity for left-behind Children and Children in Need in Rural Areas Nationwide. Minhan No. 55. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=14148&mtype= (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and The Ministry of Finance on Further Improving the Work of Ensuring Basic Living Allowances for Poverty-Stricken People. Minfa No. 69. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=14545&mtype= (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. The Directive on Reforming and Improving the Country’s Social Assistance System Released by the General Offices of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council. 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-08/25/content_5537371.htm (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice of the General Office of the Ministry of Civil Affairs and the General Office of the Ministry of Justice on Ensuring the Care and Protection of Minors in Detention and Compulsory Treatment of Drug Addicts’ Families. Minbanfa No. 24. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=14542&mtype= (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Shanghai Civil Affairs Bureau. A Circular of Proposing “Love with Children”—Work Plan of Shanghai Assistance and Care Project for Children in Need. Huminerfufa No. 2. 2020. Available online: https://mzj.sh.gov.cn/MZ_zhuzhan278_0-2-8-15-55-230/20200519/MZ_zhuzhan278_48124.html (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- “Zero infection” in the Welfare Institutions for Children and the Assistance and Protection Institutions for Minors. gov.cn. Xinhua News Agency. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-04/24/content_5505900.htm (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Notice of the Ministry of Civil Affairs on the Pilot Areas of the Unified National Child Assistance and Protection Hotline. Minhan No. 69. 2020. Available online: http://xxgk.mca.gov.cn:8011/gdnps/pc/content.jsp?id=14586&mtype=1 (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. 2019 Civil Affairs Development Statistical Bulletin. Available online: http://images3.mca.gov.cn/www2017/file/202009/1599546296585.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Levinson, M. Educational Ethics during a Pandemic. COVID-19 Rapid Response Impact Initiative. In COVID-19 White Paper 17; Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Gender | Place of Work | Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | Child Welfare Office, Civil Affairs Bureau | Division Director |

| 2 | Female | Government Temporary Child Care Centre | Section Chief |

| 3 | Female | Government Assistance and Protection Center for Minors | Staff Member |

| 4 | Male | Street and Civil Affairs Department | Child Welfare Supervisor |

| 5 | Male | Street and Civil Affairs Department | Child Welfare Director |

| 6 | Female | Children’s Social Work Service | Director General |

| 7 | Female | Children’s Social Work Service | Social Worker |

| 8 | Female | Children’s Social Work Service | Social Worker |

| 9 | Female | Children’s Medical Center | Medical Social Worker |

| 10 | Male | Social Work Service Agency for Children in Need Project | Social Worker |

| 11 | Male | Children’s Service Project of Social Organization | Social Worker |

| 12 | Male | Social Organization (related to child protection laws) | Senior Researcher |

| 13 | Female | Social Workers Association of the District | Deputy Secretary |

| Number | Gender | Age | Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 8 | Single-parent family, divorced parents. The boy lives with his father. The father stabbed the child with a knife him when he was drunk. |

| 2 | Male | 5 | Single-parent family and non-local registered permanent residence. The father has a slight intellectual disability and does some odd jobs for a living. There are two children in the family. The elder son has severe Type I Diabetes. The father cannot afford insulin and often forgets to inject insulin for his son. The elder son has been sent to the hospital several times for rescue. |

| 3 | Female | 14 | Single-parent family. The girl lives with her father and grandparents. The mother has seldom had contact with the girl since the divorce. The father will beat the girl quite hard when she has academic problems. The grandmother could not help but call the police. |

| 4 | Female | 13 | The girl’s mother takes drugs, gave birth out of wedlock, and does not know who the girl’s father is. The mother seldom disciplines her. The girl often stays at home alone, sometimes fools around with some hooligans, and does not come back home at night. The girl has been caught skipping classes and sleeping in class and, consequently, her academic performance is very poor. |

| 5 | Male | 10 | The boy’s father is serving a prison sentence and the mother ran away from home. The boy lives with his grandparents. The grandparents said they are unable to discipline him. The boy’s academic performance is very poor, and they do not know how to help him take classes online during the pandemic. |

| 6 | Female | 9 | Single-parent family. The girl lives with her mother, who is grumpy and demanding and often scolds and beats her. The grandparents have called the police several times. The police issued a domestic violence warning, and the Women’s Federation has also visited the family several times, but the mother was unmoved, believing this was her business and should not be considered domestic violence. |

| 7 | Female | 7 | The girl has a congenital disability (rickets) and good family conditions. The girl has reached school age but does not go to school. The school intended to send a teacher to her home to provide education, but the parents refused. They believe the girl has no future. As long as they provide care and money, there is no need for the girl to study. |

| 8 | Male | 14 | The boy’s mother passed away one month after his birth. The father left Shanghai after selling their house and seldom contacted him. Recently, the father died. The grandmother is still alive but is too old to look after the boy. At present, the boy is at his aunt’s house, but her financial condition is not very good. The boy is in a rebellious period and is unwilling to follow his aunt’s education. He often goes to the game room, Internet cafes, and other places. |

| 9 | Female | 10 | The girl was born with an underdeveloped heart and has no registered permanent residence. Her mother is a migrant worker and gave birth to her out of wedlock. The girl’s mother left her in front of a neighbor’s house and never returned. The mother said she was unable to support the girl, so she asked social worker to find the father. The girl’s father is a Shanghainese but married, so he is unwilling to take a paternity test and bear responsibility for the girl. The girl’s guardianship and household registration issues and medical problems cannot be resolved. |

| 10 | Male | 15 | Single-parent family. The boy originally lived with his father and grandfather, and his father has been receiving compulsory drug treatment. His mother left Shanghai after the divorce. Recently, the grandfather passed away suddenly, and the boy’s living situation became a problem. The neighborhood committee tried to contact his mother and found her dead. At present, the child lives alone. The boy has an aunt, but because of his father’s drug problem, the aunt is unwilling to take care of the boy. She is only willing to be responsible for the safekeeping of the inheritance left to the boy by his grandfather and pay living expenses and other relevant expenses every month. |

| 11 | Female | 8 | The family is faced with financial difficulties. The parents are getting divorced because of family disputes. The neighborhood committee mediated several times in vain. At present, neither of the parents wants the girl. The mother is somewhat disabled (poliomyelitis) and says that she cannot take care of the girl. The father also says that he does not want custody of the girl and that a daughter should be with her mother. |

| 12 | Male | 13 | The boy’s mother took drugs, gave birth out of wedlock, did not have a registered permanent residence, and did not go to school. He lives on take-out food, is very fat and lacks the ability to communicate with people. At present, the mother is forcibly abstaining from taking drugs. The mother’s boyfriend left the boy at the police station. He is living in a temporary care center now. |

| 13 | Female | 12 | The girl was born out of wedlock. Her mother is serving a prison sentence. The girl was diagnosed with schizophrenia at the end of last year and stayed at home for a year. At present, her guardian is her grandmother, who is too old and sick to look after her. |

| 14 | Male, Female, Male | 6, 5, 3 | All three children were born out of wedlock. Both parents are drug addicts. Since March 2012, the mother has been involved in drug trafficking. As she was pregnant at the time, she served her sentence in the community. The mother was arrested for drug trafficking on March 6, 2018, and the total sentence was nearly 18 years. The eldest son’s father has served six years in prison and will be released in 2020. The fathers of the other two children are unknown. The three children are temporarily under the supervision of their grandmother, who is also a drug addict and has just completed three years of drug rehabilitation. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, F.; Zhu, N.; Hämäläinen, J. Protection of Children in Difficulty in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010279

Zhao F, Zhu N, Hämäläinen J. Protection of Children in Difficulty in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010279

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Fang, Ning Zhu, and Juha Hämäläinen. 2021. "Protection of Children in Difficulty in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010279

APA StyleZhao, F., Zhu, N., & Hämäläinen, J. (2021). Protection of Children in Difficulty in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 13(1), 279. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010279