Abstract

Although employee green creativity is recognized as the key to the innovation in green enterprises, few studies explores the measurement of green creativity for employees. To address the gap, the present study identifies the major dimensions of employee green creativity and develops a comprehensive, reliable, and valid measurement instrument. According to the 4P’s model of creativity, four core dimensions of employee green creativity are identified, namely, green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome. Strictly adhering to the process of scale development, employee green creativity scale (EGCS) is constructed and validated. We first develop the items of employee green creativity based on literature review and expertise from academics and practitioners. Next, we examine the validation of EGCS through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis using a sample from three large-scale green enterprises (N = 460). Further, we also check the nomological validity of EGCS by testing the effects of determinants (e.g., green transformational leadership, shared vision, and green self-efficacy) on employee green creativity using a new sample from another two green enterprises (N = 169). Results reveal that EGCS is a reliable and valid instrument for capturing employee green creativity in multiple contexts. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Due to the continuous deterioration of the environment, now people become increasingly conscious of the importance to purchase and use the products that are environmentally friendly (i.e., green products) [1]. To satisfy the emerging demand of green market, green enterprises striving to produce and popularize green products appear all over the world [2]. Green creativity, as a critical capacity to produce novel and useful ideas about green product development, has received extensive attention from green enterprises [3,4]. Existing literature demonstrate that green creativity is positively related to green product development performance [3,5], and is argued to promote green innovation [6], sustainability [7], and sustainable development [8]. Over the past decade, research on organizational support for green creativity [8] and on the stance of a green enterprise to act creatively [6] has significantly progressed. Scholars also note the specific roles of employees at different managerial levels to ensure successful green product development [9,10].

Up to now, many scholars define creativity as the ability to produce novel and useful ideas [11,12,13]. In line with the notion of creativity, existing methods for measuring creativity mainly focus on assessing the novelty [14,15,16] and usefulness [17] of products. However, there have been few attempts to explore the measurement of green creativity for employees in green enterprises. Different from normal products mainly focusing on economic benefits, green product development aims to not only reduce the environmental burden but also help enterprises gain advantages in the competition [18]. Therefore, the measurement of green creativity should also be distinctive from general creativity. To address this research gap, the present study looks at a very different way to assess employee green creativity by developing a comprehensive, reliable, and valid measurement instrument—employee green creativity scale (EGCS)—which captures the four distinct dimensions including green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome.

Specifically, we develop items (i.e., specific statements that respondents are asked to evaluate by giving them a quantitative value on any kind of subjective or objective dimension) for EGCS based on literature review and expertise from academics and practitioners. Moreover, strictly adhering to the process of scale development, we first examine the factorial structure of the items in EGCS by exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Next, we conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to check the four-dimensional model of employee green creativity. The results of convergent and discriminant validity highly support the structure of EGCS. Last, we analyze the predictive validity which further examines the nomological validity of EGCS.

The present research contributes to the development of theory and practice from several aspects. First, we advance the understanding of employee green creativity by identifying the major dimensions based on an extensive literature review. We provide a comprehensive way to measure employee green creativity from four major dimensions, including green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome. Second, we set a critical precondition for theoretical advancement in the field of green creativity, as construct clarity is recognized as the foundation of theory [19]. Third, we provide practitioners with more operable criteria to evaluate the level of employee green creativity. In addition, it is operable for managers of green product development to preselect for talents. Our EGCS can be used to provide an important reference for such means.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Literature Review: Green Creativity

Creativity refers to the ability to produce novel and appropriate ideas [11,12,13]. To comprehensively uncover the nature of creativity, Rhodes proposes a 4P’s model of creativity. The model assesses creativity in four different ways, including person, process, press, and products [20]. Specifically, the term “person” refers to the creative attributes of individuals, e.g., personality, thinking styles, and intelligence. The term "process" depicts the personal behaviors to achieve creative goals, e.g., learning, perception, and communication. The term “press” means the creative environment, like external and internal sources. The term "product" reflects creative outcomes, like novel and useful ideas, solutions, and products.

In the last decade, scholars introduce creativity into the emerging research domain of green behaviors [3,4]. The roles of green creativity are argued to be the premise of green innovation [8]. Chen and Chang initially propose the concept of green creativity [3]. Referring to the notion of creativity, they defined it as the production of new and useful ideas about green products. Although this definition is widely applied in the research field of green creativity, it can only reflect in the dimension of product. However, it is hard to say whether the product can completely account for green creativity. Because it is unreasonable for managers to judge a new comer without any experience of green product R&D as a person with no or low level of green creativity. To solve this problem, we put forward to an integrative definition of green creativity as a comprehensive capacity for employees to develop green products. In line with the 4P’s model of creativity, we develop a multi-dimensional model of green creativity for employees as follow.

2.2. Dimensions of Employee Green Creativity

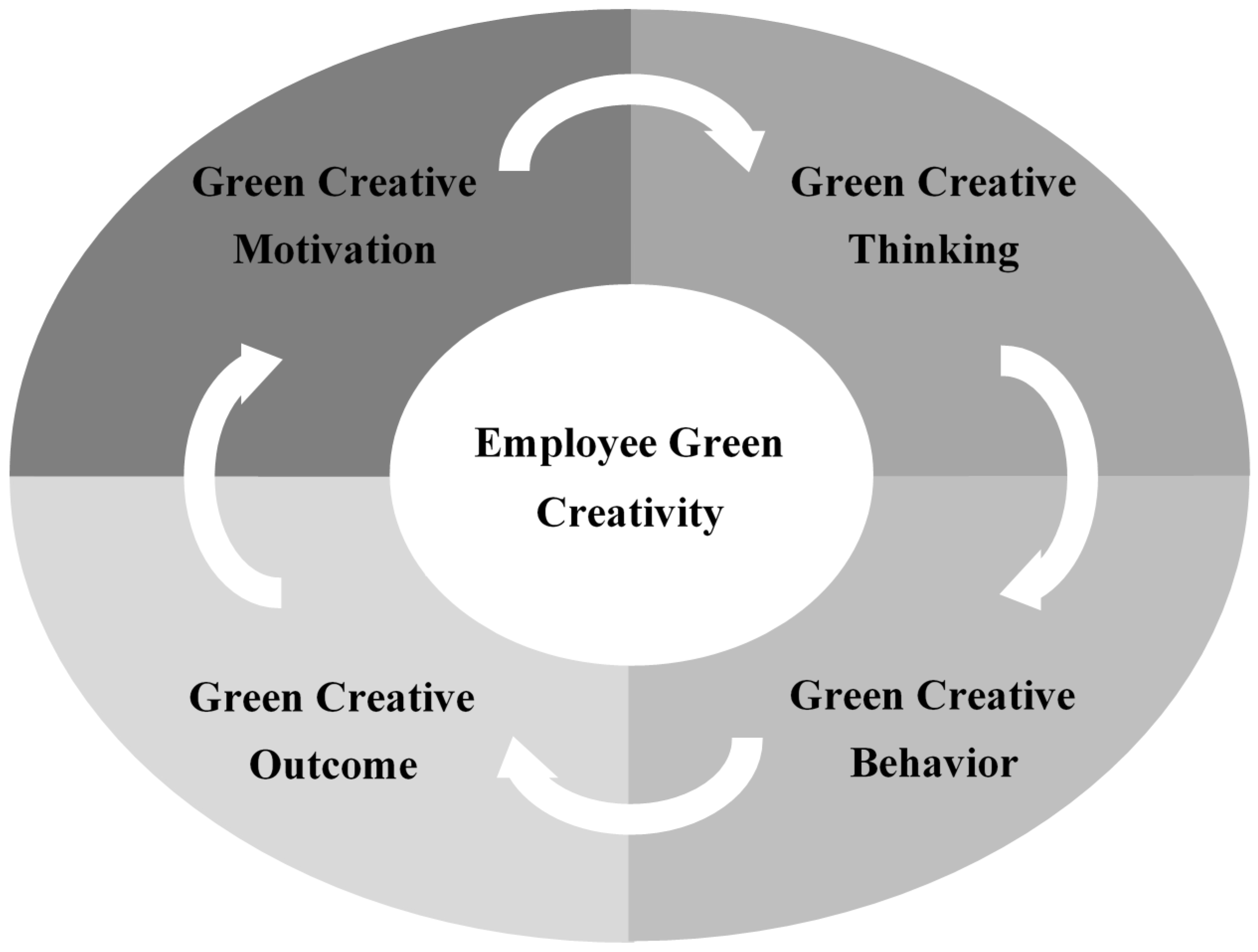

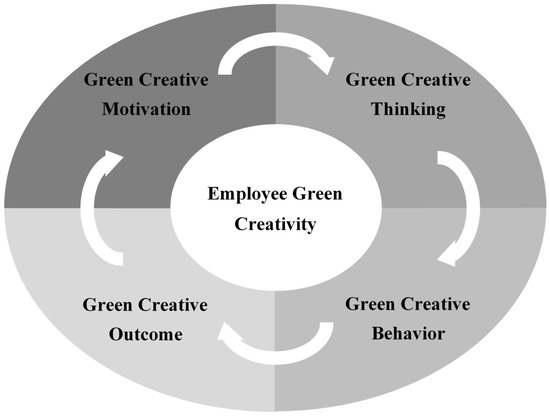

By adapting the 4P’s model, we propose a four-dimensional model of employee green creativity, which identifies four “bases” of green creativity: green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome. Accordingly, green creative motivation represents the dimension of press; green creative thinking represents the dimension of person; green creative behavior represents the dimension of process; green creative outcome represents the dimension of product. To further confirm the rationality of our four-dimensional model of green creativity, we conduct an extensive review of the green creativity literature. Table 1 provides the mapping of green creativity dimensions in existing literatures with our four-dimensional model using a sampling of nine studies. Through literature review, we find a generic typology of green creativity, consisting of the four dimensions: green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome. These four dimensions are conceptually distinct because they represent different elements of green creativity. More importantly, these four dimensions provide a comprehensive approach to assess green creativity for employees since most of the dimensions discussed in the literatures can be reconciled within the dimensions (see details in Table 1). Hence, this typology of green creativity is appliable as the theoretical basis for the proposed green creativity measures.

Table 1.

Mapping of Green Creativity Dimensions with the Four Dimensions.

“Green creative motivation”: The first dimension, green creative motivation refers to intrinsic desires for developing novel and useful ideas about green products. Such intrinsic desires can motivate employees to proactively engage in the creative process to develop green products by facilitating creative self-efficacy [27]. Specifically, employees with strong intrinsic motivations will perceive their ability to act in the environment and, thus, the creative ideas about green products will be effectively improved. Moreover, green creative motivation helps employees form an “internal causality chain”, which stimulates them to perceive valuable for the results of their creative actions in the process of green product development [28]. Scholars have also demonstrated that intrinsic motivation improves creativity by enhancing cognitive flexibility [29]. That is, when developing green products, intrinsically motivated employees are more likely to generate creative ideas about green products than those without green creative motivation.

“Green creative thinking”: Green creative motivation is not adequate for forming green creativity, employees must also rely on their creative thinking, e.g., cognitive style and flexibility. The second dimension, green creative thinking means the cognitive capacities for developing novel and useful ideas about green products. Personal creative thinking is the basis of creativity throughout the creative process, such as problem finding and solving and solution implementation [30]. Specifically, employees need to think about green-related problems fluently, flexibly, elaborately, and lastingly. Employees exhibiting creative cognitive styles tend to search for and integrate creative-problem-related information from a variety of sources and redefine problems [31]. Moreover, employees with cognitive flexibility specialize in capturing creative insights and broadening cognitive categories [32].

“Green creative behavior”: As green product development is a dynamic and complex process, employees need to carry out various activities, e.g., learning new skills, communicating, and sharing knowledge with others. The third dimension, green creative behavior means the capacities to carry out activities for developing novel and useful ideas about green products. To accomplish a complicated creative goal, employees need to collaborate with colleagues, share knowledge and skills, and acquire information in diverse ways [33]. Green creative behavior is the key to realize creative ideas about green products. When developing green products, employees need to focus on not only holding static capacities but also improving dynamic capacities via a series of creative activities [34], for example, learning, collision, inspiration through repeated discussion, experiment, and verification.

“Green creative outcome”: Undoubtedly, it is important for employees in green enterprises to achieve creative outcomes, e.g., developing green service and products. The last dimension, green creative outcome means the capacities to realize creative goals of developing novel and useful ideas about green products. Here, we emphasize the speed, quantity, quality, and value of the creative ideas when employees develop and implement green products [35]. To keep the system of green product development stable, it is necessary for employees not only to input a large number of resources, like time, human, material, and financial supports, but also to output creative outcomes [36]. Therefore, similar to the mainstream view of existing literature [3], the current research sets green creative outcome as one of the main dimensions of green creativity for employees.

Figure 1 illustrates the four-dimensional model of employee green creativity. In conclusion, employee green creativity is a comprehensive capability that integrates green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome.

Figure 1.

Four-dimensional model of employee green creativity.

2.3. Nomological Model of Employee Green Creativity

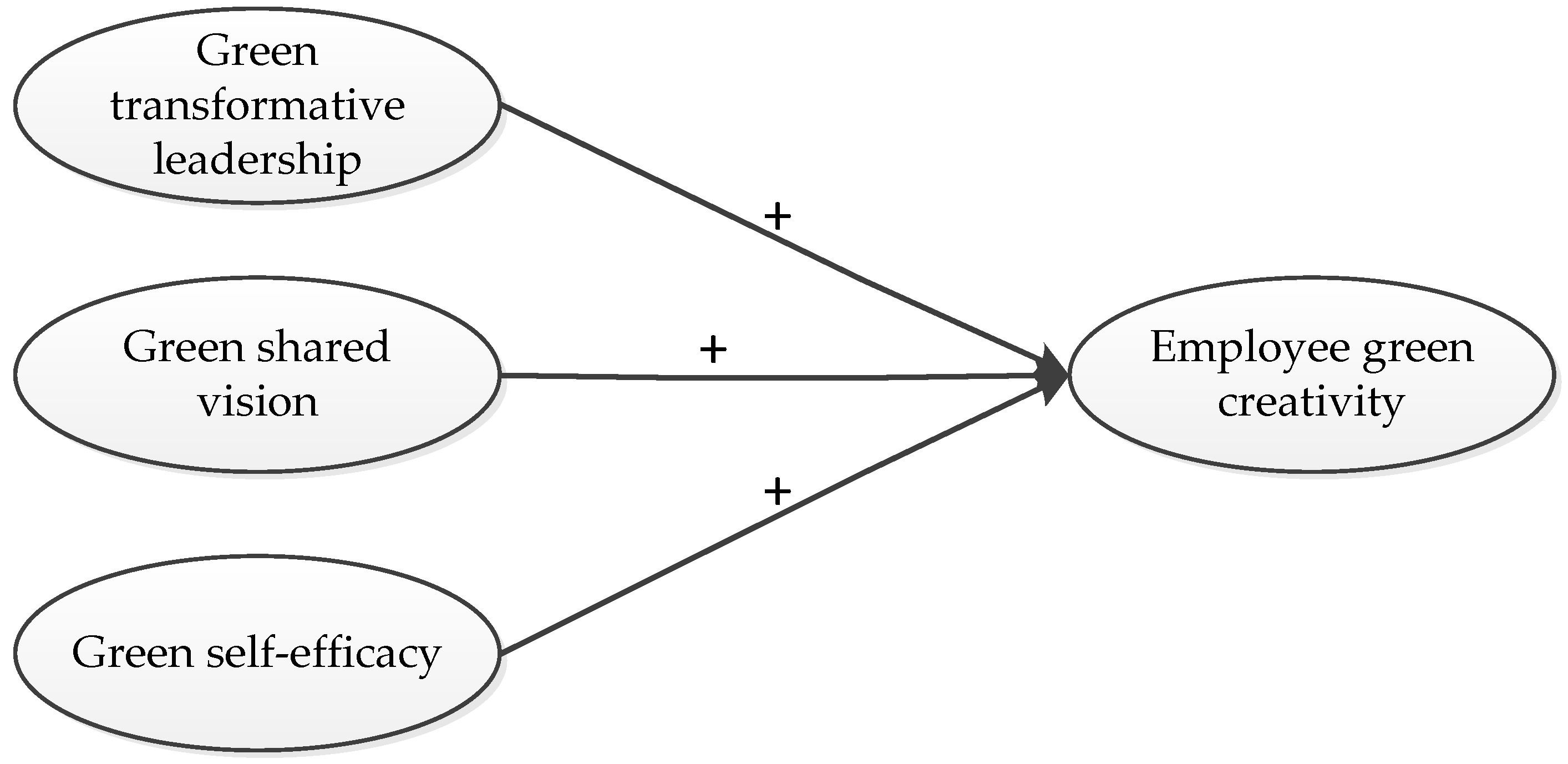

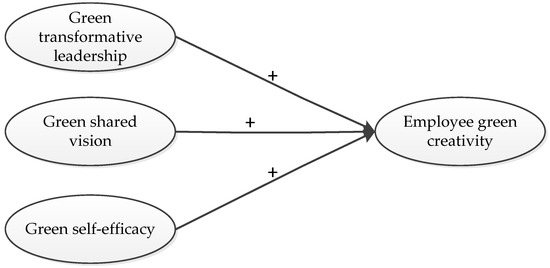

Having conceptualized employee green creativity as a comprehensive capacity with four distinct dimensions, we specify the concept within a nomological network of related green variables to examine the predictive validity of the scale developed in our research. According to existing literatures, we propose a nomological network by introducing green transformational leadership, green shared vision, and green self-efficacy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Nomological model of employee green creativity. Notes. + means the positive relationship between independent and dependent variables.

Green transformational leadership refers to a style of leadership in which leaders encourage, inspire, and motivate employees to engage in green innovation [37]. Employee creativity highly depends on the characteristics of leaders, especially for transformational leadership, as they play a critical role in changing the working environment [38]. When working with transformational leadership, employees’ creative thinking will be highly encouraged [39]. Researchers have demonstrated that transformational leadership highly facilitates employee creativity [40]. On the basis of previous studies, Chen and Chang adapt the concept of green transformational leadership, a leadership style that encourages, motivates, and supports followers to achieve environmental goals [3]. Based on an empirical study in the electronics industry, they demonstrate the positive effect of green transformational leadership on employee green creativity. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Green transformational leadership positively relates to employee green creativity.

Green shared vision refers to a collective vision of environmental goals that are internalized in an organization [41]. Researchers have revealed that a shared vision helps employees form a common insight and objective in an organization [42]. In support of a shared vision in an organization, employees can fluently identify, absorb, and recombine different ideas, knowledge, skills, and technologies to further enhance creativity [43]. Moreover, a common organizational strategy provided by a shared vision motivates employees to work toward organizational goals, such that it enables them to be more creative [12]. In the environmental era, to meet global green needs, green shared vision is important for green creativity. Through empirical analysis, Chen et al. demonstrate the positive effect of green shared vision on green creativity [4]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Green shared vision positively relates to employee green creativity.

In general, green self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to achieve a designated performance in green jobs [4]. Researchers have demonstrated that individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy are more likely to achieve good performance, as employees who perceive themselves as highly competent would put more effort into their work [44]. When engaging in creative activities, employees with higher self-efficacy have more confidence in their own capacities to develop novel and useful ideas. In the environmental era, green self-efficacy makes employees pay attention to green-related activities, stimulates employees’ creative motivations and behavior to achieve environmental goals. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Green self-efficacy positively relates to employee green creativity.

3. Materials and Methods

According to the guidance of scale development [45], we developed a novel scale for measuring employee green creativity. First, we designed the items of EGCS through expert review. After initial processing on the original scale, we distributed surveys to a large sample of R&D staff in green enterprises. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted to provide insights into the quality of EGCS. Next, we collected data from a new sample of R&D staff to further check the predictive validity of EGCS. Three mature theoretical assumptions in the field of green creativity, namely, the notion of green transformational leadership [10], shared vision [4], and organizational identity [6] were introduced to construct the nomological network of employee green creativity.

3.1. Initial Scale Construction

We invited six experts from the fields of creativity, green innovation, and organizational behaviors (two professors, three associate professors, and one assistant professor) to separately generate items involving employee green creativity. All the experts are senior scholars at the prestigious colleges and universities in China (e.g., Zhejiang University, Harbin Institute of Technology, and Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics). In addition, they also have strong research and publication backgrounds (e.g., their researches have been published on the mainstream journals in the domain of creativity (e.g., Journal of Creativity Research and Journal of Creative Behavior) and those in the domain of environmental behaviors (e.g., Sustainability). According to the deductive method of item development [46], we provided all the experts with a short reference list, our conceptualization of employee green creativity, and some considerations about item development. The experts were requested to develop around 12 items each to ensure a large enough pool of items. All the experts generated a total of 32 items.

Next, we further processed the initial items by analyzing content, deleting double items, and adjusting item length. In this process, 12 items were deleted for having similar content or topic. The remaining items were provided to three practitioners (Mtenure = 12.56 years) who had rich experience in green product development for further adjusting. Thereafter, all experts and practitioners were requested to rate the clarity of the items and the extent to which the items reflected the construct of employee green creativity. Lastly, we selected the 16 items that comprise EGCS.

3.2. Scale Validation Analysis

3.2.1. Data Collection

We collected data using an online questionnaire in three large-scale green enterprises. Personnel managers provided access to the email addresses of research and development (R&D) staff. Enterprise A focuses on developing green-energy technologies, especially for solar photovoltaic panels. The core business of Enterprise B is to develop new pro-environmental building materials, such as environmental protection pipes, paints, and wall materials. Enterprise C is committed to developing environmental-protection packing materials such as expanded-polyethylene (EPE), polyethylene foam, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) sheets.

After receiving an email containing information about our study, participants were requested to complete the online questionnaire through a survey link. The investigation lasted for 3 months. We issued 563 survey invitations, and 460 valid questionnaires were recovered (response rate = 81.71%). Participants were 44.35% female with an average age of 30.89 years (standard deviation (SD) = 7.24). A total of 76.30% of participants held a university degree or higher. They had spent an average of 6 years (SD = 4.61) in green product development.

3.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

First, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to examine the factorial structure of the 16 items. The result of the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of 0.84 confirmed an abundant sample size. Bartlett’s test of sphericity exhibited a result of approximately, which testified that our data were qualified for factor analysis [47].

We introduced principal component analysis (PCA) to extract factors using a standard of the characteristic root larger than 1 and rotated those using the varimax method. The four factors explained 60.72% of the variance. Principal component factor 1 reflected green creative motivation (factor loadings (FLs) > 0.50; α = 0.80), principal component factor 2 reflected green creative thinking (FLs > 0.50; α = 0.78), principal component factor 3 reflected green creative outcome (FLs > 0.50; α = 0.78), and principal component factor 4 reflected green creative behavior (FLs > 0.50; α = 0.76). Pearson’s correlations ranged from 0.25 to 0.30 between dimensions (the details of EFA are given in Table 2).

Table 2.

Items, means (M), standard deviations (SD), Cronbach’s alphas (α), and factor loadings.

3.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

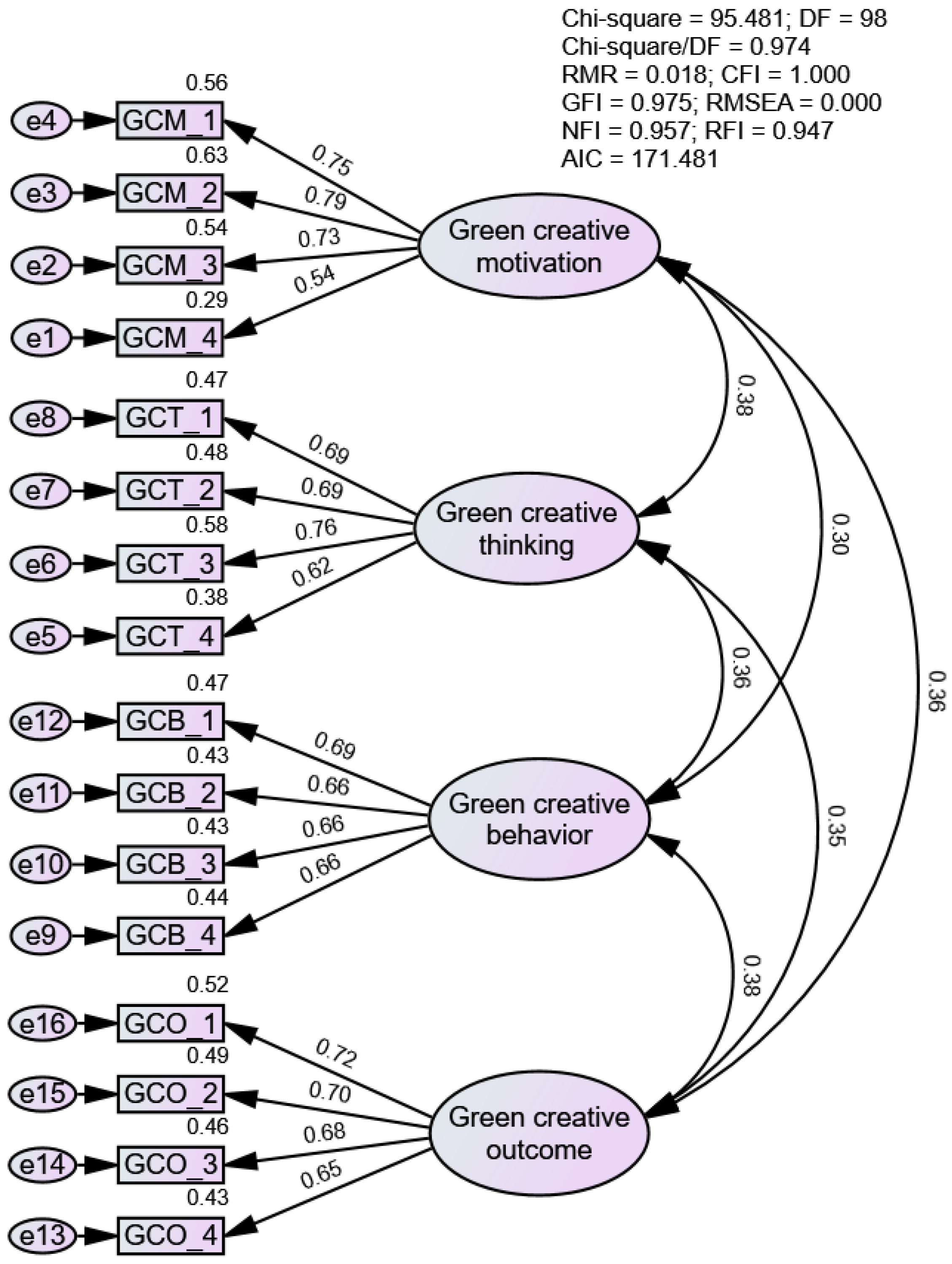

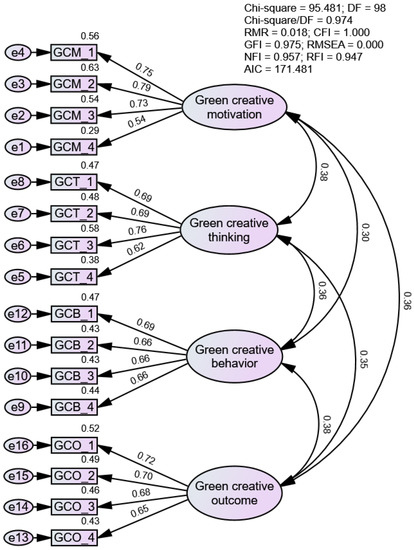

To check the validity of the four-dimensional structure model of employee green creativity, we used IBM SPSS AMOS 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Initially, we established a four-factor model based on our conceptualization of employee green creativity. Specifically, four latent variables were created: green creative motivation (4 items), green creative thinking (4 items), green creative behavior (4 items), and green creative outcome (4 items).

First, we assessed the convergent and discriminant validity of EGCS by composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). It is recommended that the CR should be larger than 0.7 and the AVE should be larger than 0.5 [48]. Table 3 shows that the CR values of four latent variables ranged from 0.76 to 0.80 and the AVE values ranged from 0.44 to 0.51. Although the AVE values of GCT, GCB, and GCO were less than 0.5, the convergent validity can be still acceptable because all the CR values of latent variables were larger than 0.7 [48,49].

Table 3.

Convergent and discriminant validity.

According to the guidance of Fornell and Larcker [48], the divergent validity of a specific scale will be supported when all the square roots of AVE are greater than their corresponding correlation. Table 3 shows that all the square roots of AVE (0.71, 0.69, 0.66, and 0.69) were greater than the corresponding squared correlations (0.30–0.39). Therefore, the results support the discriminant validity of our four-dimensional model of employee green creativity.

To assess the model fit, we examined the eight indicators of (threshold values from 1 to 3), root-mean-square residual (RMR; threshold values below 0.50), comparison of fit index (CFI; threshold values above 0.95), goodness-of-fit index (GFI; threshold values above 0.95), root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; threshold values below 0.60), normed fit index (NFI; threshold values above 0.95), and relative fit index (RFI; threshold values above 0.95). Moreover, we measured the Akaike information criterion (AIC), a popular indicator for comparing the extent of model fit, to conduct comparative analysis between the one- and four-factor models. A lower level of AIC indicates a better trade-off between the fit and complexity of different models [50]. Figure 3 shows a good model fit: = 0.97; RMR = 0.18; CFI = 1.00; GFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.00; NFI = 0.96; RFI = 0.95. More importantly, the four-factor model had a lower AIC value (171.48) than that of the one-factor model (1153.94). The results confirmed that our four-factor model well represents the conceptualization of employee green creativity.

Figure 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis—four-factor employee green creativity scale (EGCS) scale.

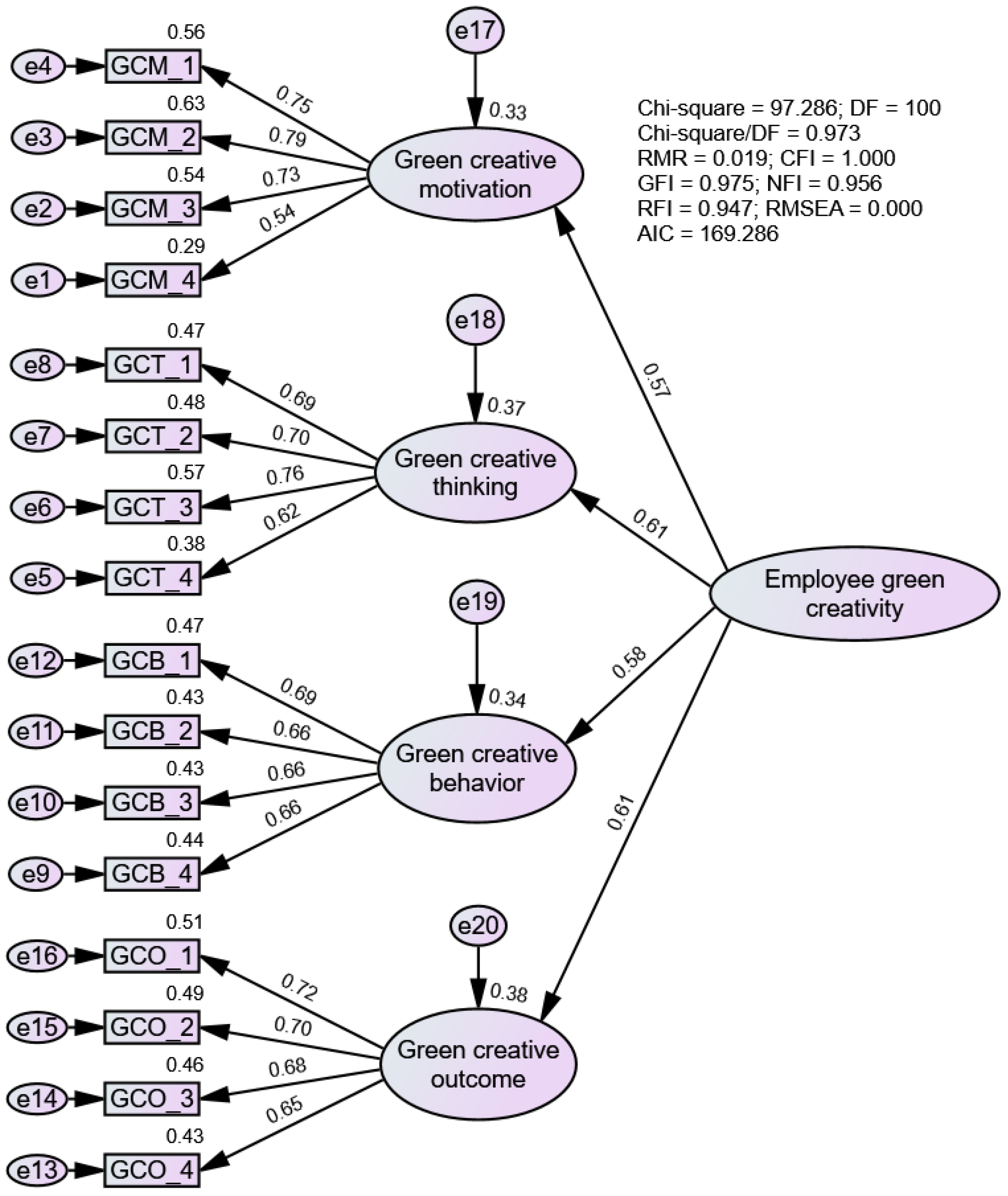

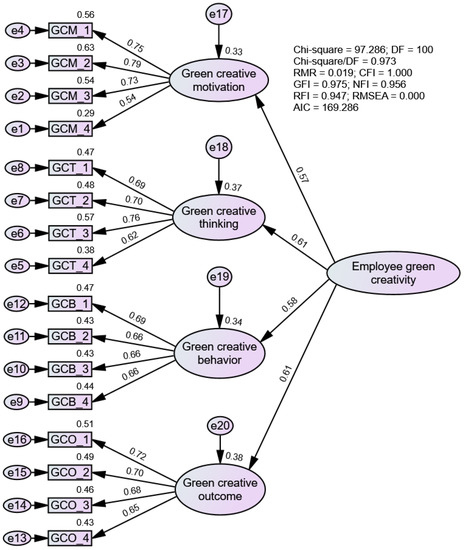

3.2.4. Second-Order Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In line with the guidance of March and Hocevar, a higher-order construct maybe exist if there is a high degree of correlation between first-order factors [51]. Based on the results above, we suppose that there may be a second-order construct—employee green creativity—beyond the four first-order factors. Figure 4 indicates the results of the second-order factor structure with the four dimensions. All the indicators well supported the second-order factor structure of EGCS. The result indicated that when developing green products, employees not only require the four dimensions of capacities, but also the overall green creativity as a higher-order capacity that included a capacity common to all the four dimensions. In other words, employees evaluated green creativity as a whole capacity rather than in isolation.

Figure 4.

Second-order factor structure of EGCS.

3.3. Predictive Validity Analysis

3.3.1. Data Collection

We analyzed the predictive validity of EGCS by testing Hypotheses 1–3 specified in Figure 2. We collected data from a new sample—R&D staff in another two large-scale green enterprises that were committed to developing and manufacturing new-energy vehicles. After receiving an email containing information about our study, participants were requested to complete our online questionnaire via a survey link. The investigation lasted for 1 month. We issued 248 survey invitations, and 169 valid questionnaires were recovered (response rate = 68.15%). Participants were 44.97% female with an average age of 31.27 years (SD = 7.20). A total of 73.96% of the participants held a university degree or higher. They had spent an average of 6.20 years (SD = 4.51) in green product development.

3.3.2. Measures

All measures were administered in Chinese. We recruited a professional translator to translate the questionnaire from English to Chinese, and a second translator for back-translation to ensure equivalency between languages. Employee green creativity was measured with 16 items of EGCS (α = 0.88), which consisted of 4 items from green creative motivation (α = 0.90), 4 items from green creative thinking (α = 0.86), 4 items from green creative behavior (α = 0.93), and 4 items from green creative outcome (α = 0.88). Participants were requested to rate the items on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Green transformational leadership was measured using the 6-item scale developed by Chen and Chang (2013) [3]. Example items include, “The leader of the green product development project inspires the project members with the environmental plans.” and “The leader of the green product development project gets the project members to work together for the same environmental goals.” Participants were requested to rate the items on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Results of Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.94) showed the high reliability of the scale.

Green shared vision was measured with the 4-item scale developed by Chen et al. (2015) [4]. Example items include, “There is commonality of environmental goals in the company.” and “There is total agreement on the company’s strategic environmental direction.” Participants were requested to rate the items on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha results (α = 0.92) showed the high reliability of the scale.

Green self-efficacy was measured with the 6-item scale developed by Chen et al. (2015) [4]. Example items include, “I feel I can succeed in accomplishing environmental ideas.” and “I feel competent to effectively deal with environmental tasks.” Participants were requested to rate the items on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha results (α = 0.80) showed the high reliability of the scale.

3.3.3. Data Analysis

To test Hypotheses 1–3, we first examined correlations between variables controlling for age, gender, education, and tenure. Green transformational leadership was positively related to employee green creativity (r = 0.33, p < 0.01). Moreover, green transformational leadership was positively related to the four sub-dimensions. Green shared vision was positively related to employee green creativity (r = 0.31, p < 0.01). Moreover, green shared vision also positively related to the four sub-dimensions, except for green creative thinking. Green self-efficacy was positively related to employee green creativity (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). Moreover, green self-efficacy was also positively related to the four sub-dimensions (see details in Table 4).

Table 4.

Means, standard deviation, and Pearson correlation matrix (N = 169).

Next, we conducted three regression models, setting employee green creativity as the dependent variable, and controlling for age, gender, education, and tenure (see Table 5). Consistent with Hypothesis 1, Model 1 showed a positive effect of green transformational leadership on employee green creativity (β = 0.29, p < 0.01). In line with Hypothesis 2, Model 2 showed a positive effect of green shared vision on employee green creativity (β = 0.23, p < 0.01). In support of Hypothesis 3, Model 3 showed a positive effect of green self-efficacy on employee green creativity (β = 0.31, p < 0.01). In conclusion, the results strongly support the predictive validity of EGCS.

Table 5.

Regression models of employee green creativity.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Although existing literatures have clarified the role of creative employees within a green enterprise, there is still no comprehensive conceptualization of employee green creativity. To address the gap, the current research developed a reliable and valid scale that can effectively measure employee green creativity. According to the process of scale development, after initial scale construction, we firstly conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA), which showed that EGCS consisted of four principal components representing distinct dimensions of employee green creativity. The finding provided a preliminary support for the four-dimensional measure of employee green creativity with reliable responses. Next, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and found when developing green products, it is necessary for employees to possess four major capacities, including green creative motivation, thinking, behavior, and outcome. The second-order CFA indicates that the four capacities are highly corelated and produce a higher-order factor structure—employee green creativity. The findings show that our four-dimensional model present a novel and distinct conceptualization of employee green creativity from the existing mainstream views (e.g., Chen and Chang [3], Song and Yu [6], and Jia et al. [9]). Last, to confirm the nomological model of employee green creativity, we further conduct a predictive validity analysis. The positive effects of green transformational leadership [40], green shared vision [42], and green self-efficacy [4] on employee green creativity satisfied the predictive validity requirement of EGCS.

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

In terms of theoretical implications, our EGCS provides new insights and extends the theoretical understanding of employee green creativity. Researchers have noted that green creativity reflects a complex system integrating the inherent personal knowledge, beliefs, and values [21]. However, existing definitions, as a product of consequentialism, mainly focus on employees’ capacity to produce creative outcomes. They ignore the fact that it is a long-term and multi-factorial process for employees to develop green products. Our multi-dimensional model works well to integrate several core sub-capacities into employee green creativity. Moreover, our results show that employee green creativity and its sub-dimensions are positively related to environmental factors in an organization (i.e., green transformational leadership and shared vision) [4,10]. The findings expand the current evidence of the relationships between organizational supports and employees’ whole level of green creativity and part-level of creative capacities. In addition, our results revealed that employee green creativity and its sub-dimensions are positively related to individual cognition (i.e., green self-efficacy) [4]. This finding enriches our understanding of the relationship between green cognition and employees’ whole level of green creativity and part-level of creative capacities.

This research also provides several practical implications. First, the comprehensive concept of employee green creativity helps practitioners to further understand the nature of employee green creativity. According to our findings, managers should evaluate employees’ capacities of developing green products depending on the four major capacities rather than the final outcome. It is useful for practitioners when they set comprehensive criterion to evaluate employees’ green creativity. Our EGCS is also operable for managers to preselect for talents in a green organization, where it can be used to provide an important reference for such means. Most importantly, the multi-dimensional model of employee green creativity is a key guidance for enterprises to simultaneously cultivate talents in multiple ways rather than only from the final outcome.

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

While the present research develops and validates a comprehensive employee green creativity scale, it still has limitations. Although we collected data from multiple heterogeneous samples, we do not consider the influence of the enterprise scale, which may cause a diverse response outcome. It is plausible that large-scale enterprises pay more attention to social responsibility and product R&D than small enterprises do. In addition, employee green creativity is expected to influence firm-level green creativity, and vice versa [52]. Future studies can develop measurements at multiple levels to investigate green creativity. More importantly, creativity evaluation of personnel should be confirmed by their actual capability to produce creative outcomes. Although we measure it using the speed, quantity, quality, and value of the ideas when employees develop and implement green products, it is still necessary to systematically and comprehensively evaluate ideation outcomes in according to the context of specific research.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, H.J.; writing—review and editing, K.W.; formal analysis, Z.L.; validation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.W.; data curation, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 71704153, 71701180, 71801187), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2018M642472), and the Plan of Youth Innovation Team Development of Colleges and Universities in Shandong Province (SD2019-161).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in FigShare at [10.6084/m9.figshare.13498689].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Spielmann, N. Green is the new white: How virtue motivates green product purchase. J. Bus. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinevich, V.; Huber, F.; Karataş-Özkan, M.; Yavuz, Ç. Green entrepreneurship in the sharing economy: Utilizing multiplicity of institutional logics. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 52, 859–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, T.W.; Lin, C.Y.; Lai, P.Y.; Wang, K.H. The influence of proactive green innovation and reactive green innovation on green product development performance: The mediation role of green creativity. Sustainability 2016, 8, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Yu, H. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Creativity and organizational learning as means to foster sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Kraslawski, A. Creativity enables sustainable development: Supplier engagement as a boundary condition for the positive effect on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Chin, T.; Hu, D. The continuous mediating effects of GHRM on employees’ green passion via transformational leadership and green creativity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Dhar, R.L. Effect of green transformational leadership on green creativity: A study of tourist hotels. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Conti, R.; Coon, H.; Lazenby, J.; Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1154–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. When is educational specialization heterogeneity related to creativity in research and development teams? Transformational leadership as a moderator. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pillemer, J. Perspectives on the social psychology of creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, S. Design creativity: Refined method for novelty assessment. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 7, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorineschi, L.; Frillici, F.S.; Rotini, F. Impact of missing attributes on the novelty metric of Shah et al. Res. Eng. Des. 2020, 31, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Chakrabarti, A. Assessing design creativity. Des. Stud. 2011, 32, 348–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorineschi, L.; Frillici, F.S.; Rotini, F. Issues Related to Missing Attributes in A-Posteriori Novelty Assessments. In Proceedings of the 15th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 May 2018; pp. 1067–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Tariq, A.; Badir, Y.F.; Tariq, W.; Bhutta, U.S. Drivers and consequences of green product and process innovation: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future outlook. Technol. Soc. 2017, 51, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R. Editor’s comments: Construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, M. An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappan 1961, 42, 305–310. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, L.T. Environmentally-specific servant leadership and green creativity among tourism employees: Dual mediation paths. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 86–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Yan, J. Commitment to human resource management of the top management team for green creativity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Dhar, R.L. Green training in enhancing green creativity via green dynamic capabilities in the Indian handicraft sector: The moderating effect of resource commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 121948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Afsar, B. Green human resource management and employees’ green creativity: The roles of green behavioral intention and individual green values. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, F.; Wang, X. How green transformational leadership affects green creativity: Creative process engagement as intermediary bond and green innovation strategy as boundary spanner. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Effect of workplace status on green creativity: An empirical study. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 8763–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, V.; Sutton, C.; Sauser, W. Creativity and certain personality traits: Understanding the mediating effect of intrinsic motivation. Creat. Res. J. 2008, 20, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Woodman, R.W. Creativity and intrinsic motivation: Exploring a complex relationship. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 52, 342–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2016, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, D.C.; Scott, G.M.; Mumford, M.D. Evaluative aspects of creative thought: Effects of appraisal and revision standards. Creat. Res. J. 2004, 16, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.C. Interactive effects of environmental experience and innovative cognitive style on student creativity in product design. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 27, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreu, C.K.W.D.; Nijstad, B.A.; Baas, M. Behavioral activation links to creativity because of increased cognitive flexibility. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2010, 2, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, R.; Smith, D.C.; Park, C.W. Cross-functional product development teams, creativity, and the innovativeness of new consumer products. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, P.B. Groups, teams, and creativity: The creative potential of idea-generating groups. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 49, 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.L.A.; Fan, H.L. Organizational innovation climate and creative outcomes: Exploring the moderating effect of time pressure. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S.K.; Horwitz, I.B. The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: A meta-analytic review of team demography. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 987–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, W. Value congruence: A study of green transformational leadership and employee green behavior. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Schatzel, E.A.; Moneta, G.B.; Kramer, S.J. Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. Leadersh. Quart. 2004, 15, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Farh, J.L. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, E.; Díez-de-Castro, E.P.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. Linking employee stakeholders to environmental performance: The role of proactive environmental strategies and shared vision. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 128, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Chen, T.J. Collective psychological capital: Linking shared leadership, organizational commitment, and creativity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.S.; Kozlowski, S.W.J. Goal orientation and ability: Inter goal orientation and ability: Interactive effects on self-efficacy, performance, and knowledge. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, G.A. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. J. Emerg. Prim. Health Care 2010, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Dash, S. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation; Pearson Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers, E.J.; Farrell, S. AIC model selection using Akaike weights. Psychon. B Rev. 2004, 11, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parjanen, S. Experiencing creativity in the organization: From individual creativity to collective creativity. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 7, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).