Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

Rural Tourism Strategies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara.

- Reserva de la Biosfera de Monfragüe.

- Sierra de Gata, Las Hurdes, Valle del Alagón.

- Tajo Internacional, Sierra de San Pedro.

- Trujillo, Miajadas, Montánchez.

- Valle del Ambroz, Tierras de Granadilla.

- Valle del Jerte, La Vera.

2.2. Cartographic Database

2.3. Alphanumeric Database

- Demographic data obtained from the different population registers from the year 2000 to 2018 of all the municipalities that make up the tourist territories of the NSI. In addition, the birth rate, the mortality rate, the natural growth rate, migration rate, aging rate, youth index, population density, and the percentage of population growth were calculated with these population data.

- Economic variables published in the Experimental Atlas of the National Statistics Institute, such as the average income per capita of the year 2018, was the variable chosen to be analyzed. Job seekers’ data was obtained from the Public State Employment Service (PSES) for the year 2018. The unemployment rate was calculated by considering the possible active population (population between 16 and 64 years old) because the active population data at the municipal level are not available.

- Heritage variables. The Assets of Cultural Interest database registered in the Register of Assets of Cultural Interest of the Ministry of Culture and Sport of the Government of Spain [46] was consulted. These Assets of Cultural Interest were georeferenced to know the number that exists in each municipality of Extremadura. Thus, the percentage per thousand inhabitants of these Assets of Cultural Interest was calculated. On the other hand, the Natural Protected Areas: the layers of the Protected Natural Spaces of Extremadura (RENPEX) were obtained from the Extremambiente website of the Junta de Extremadura [47] the Special Protection Areas for Birds (ZEPA), of the Zones of Special Conservation (ZEC), RAMSAR areas, Biosphere Reserves, Private Areas of Ecological Interest, and National Parks. The percentage of protected natural areas in each tourist territory was calculated with these data.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4.2. Pearson’s Bivariate Correlations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Godfrey, K.; Clarke, J. The Tourism Development Handbook—A Practical Approach to Planning and Marketing; Cengage Learning EMEA: Andover, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco González, M.; SantosLacueva, R. La relación entre acción pública y turismo desde diversas perspectivas: Ideas, actores e instituciones. Pasos. Rev. Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, M.; Moltó Mantero, E.; Rico, A. Las actividades turístico-residenciales en las montañas valencianas. Ería Revista Cuatrimestral de Geografía 2008, 75, 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, P. Conceptualizing Rurality. In The Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P.M., Mooney, P.T., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Sharpley, J. Rural Tourism. An Introduction; International Thomson Business Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, F. Turismo rural: Características de la actividad e impacto económico en Galicia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente, G.C.; Pérez, M.V.; Herrera, L.; Fernández, L.C. Turismo rural en Cataluña y Galicia: Algunos problemas sin resolver. Cuadernos geográficos de la Universidad de Granada 2004, 34, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cànoves, G.; Garay, L.; Duro, J.A. Turismo rural en España: Avances y retrocesos en los últimos veinte años. Papers de Turisme 2014, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. 25 Years of the Leader Initiative as European Rural Development Policy: The Case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Eur. Ctry. 2017, 9, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.A. El turismo en las ciudades históricas. Polígonos Rev. Geogr. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Sánchez, R. El turismo rural. In Estructura Económica y Configuración Territorial en España. Juan I. Pulido Fernández (coord.); Editorial Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2008; ISBN 978-84-975656-4-6. [Google Scholar]

- Yagüe, P. Rural tourism in Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Martín, F. Problemas de sostenibilidad del turismo rural en España. In Proceedings of the Anales de Geografía de la Universidad Complutense; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2011; Volume 31, pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cànoves Valiente, G.; Herrera, L.; Villarino Pérez, M. Turismo rural en España: Paisajes y usuarios, nuevos usos y nuevas visiones. Cuadernos de Turismo 2005, 15, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Almonte, J.M.J.; García, F.J.P. Población y turismo rural en territorios de baja densidad demográfica en España. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos españoles 2016, 71, 247–272. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Gurría Gascón, J.L. El modelo rural y el impacto de los programas LEADER y PRODER en Extremadura. (Propuesta metodológica). Scr. Nov. 2010, XIV, 310–347. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Engelmo Moriche, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. Análisis espacial de la ordenación territorial en áreas rurales de baja densidad demográfica: El caso de Extremadura. Papeles de Geografía 2017, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Observatorio de Turismo Rural de España. Available online: http://www.escapadarural.com/observatorio/ (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Ávila Bercial, R.; Barrado Timón, D.A. Nuevas tendencias en el desarrollo de destinos turísticos: Marcos conceptuales y operativos para su planificación y gestión. Cuadernos de turismo 2005, 15, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Leco, F.; Gurría, J.L.; Pérez, M.N. La Planificación del Turismo Rural Sostenible en Extremadura mediante SIG. In Tecnologías Geográficas para el Desarrollo Sostenible; Departamento de Geografía, Universidad de Alcalá: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2000; pp. 544–573. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, T.L.-G.; Gutiérrez, E.A. El turismo rural como agente económico: Desarrollo y distribución de la renta en la zona de Priego de Córdoba. CIRIEC-España Revista de Economía Pública Social y Cooperativa 2006, 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Luque, A. El turismo rural en España: Terminología y problemas de traducción. Entreculturas: Revista de Traducción y Comunicación Intercultural 2009, 469–486. [Google Scholar]

- Roget, F.M.; González, X.A.R. Rural tourism demand in Galicia, Spain. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez García, M.; Ruiz Chico, J.; Peña Sánchez, A.R. Incidencia de las Zonas Rurales sobre las Posibles Tipologías de Turismo Rural: El Caso de Andalucía; Asociación Española de Ciencia Regional (AECR). Investig. Reg. 2014, 28, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cánoves, G.; Pérez, M.V. Turismo en espacio rural en España: Actrices e imaginario colectivo. Documents d’anàlisi geogràfica 2000, 37, 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco, A. Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Martín, B.; Armesto López, X. Turismo, gastronomía y territorio. Actas del XI Coloquio de Geografía Rural 2002, 1, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Indicadores demográficos básicos 2000–2019. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Segui, M.; Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Armas, P.; Priestley, G.; Garay, L. Tourisme Rural en Espagne. Analyse de l’offre des Baléares, de la Galice et de la Catalogne. Espaces 2002, 194, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Javier Saez-Fernandez, F.; Jimenez-Hernandez, I.; del Sol Ostos-Rey, M. Seasonality and Efficiency of the Hotel Industry in the Balearic Islands: Implications for Economic and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fons, M.V.S.; Fierro, J.A.M.; y Patiño, M.G. Rural tourism: A sustainable alternative. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cànoves, G.; Pérez, M.V.; Herrera, L. Políticas públicas, turismo rural y sostenibilidad: Difícil equilibrio. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2006, 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas Alonso, G.; Nieto Masot, A. Towards Rural Sustainable Development? Contributions of the EAFRD 2007–2013 in Low Demographic Density Territories: The Case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.G.; de la Calle Vaquero, M. Turismo en el medio rural: Conformación y evolución de un sector productivo en plena transformación. El caso del Valle del Tiétar (Ávila). Cuadernos de turismo 2006, 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio de Turismo de Extremadura. Available online: http://observatorio.turismoextremadura.com (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Junta de Extremadura. Plan Turístico de Extremadura (2017–2020). Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/viajar/shared/documentacion/publicaciones/PlanTuristicoExtremadura2017_2020.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Colina, C.L.; Roldán, P.L. Anàlisi Multivariable de Dades Estadístiques; Universidad Autònoma de Barcelona: Bellaterra, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadras, C.M. Nuevos Métodos de Análisis Multivariante; CMC Editions Barcelona: Bellaterra, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Cos Guerra, O.; Reques Velasco, P. Vulnerabilidad territorial y demográfica en España. Posibilidades del análisis multicriterio y la lógica difusa para la definición de patrones espaciale. J. Reg. Res. 2019, 45, 201–255. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Posada, J.A.; Galindo, M.P. Estadística Multivariante: Análisis de Correlaciones; Amarú: Salamanca, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, D. Análisis de Datos Multivariantes. In Madrid: McGraw Hills; Interamericana de España: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación. In Mexico: McGraw Hills; Interamericana: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Buzai, G.D.; Baxendale, C.A. Análisis socioespacial con sistemas de información geográfica marco conceptual basado en la teoría de la geografía. Ciencias Espaciales 2015, 8, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccioli, F.; Franiti, R.; Boncinelli, F.; Asmar, T.E.; Asmar, J.P.E.; Casini, L. Spatial analysis of selected biodiversity features in protected areas: A case study in tuscany region. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. The rural development policy in Extremadura (SW Spain): Spatial location analysis of leader projects. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte. Patrimonio Cultural. Available online: http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura-mecd/areas-cultura/patrimonio (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremambiente. Conservación de la Naturaleza y Áreas Protegidas. Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Uriel, E. Análisis de datos. Series temporales y análisis multivariante. Ed. Ac. Madr. 1995, 430. [Google Scholar]

- Mallo, F. Análisis de Componentes Principales y Técnicas Factoriales Relacionadas; Universidad de León: León, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, I. A user’s Guide to Principal Components; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Garson, G. QASS Analysis of variance monographs: A computer-focused review. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 1999, 17, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G. QASS Analysis of variance monographs: A computer-focused review. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 1999, 17, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarès-Barberà, M.; Vera, A.; Tulla i Pujol, A.F.; Badia i Perpinyà, A.; Ruiz, P.S. Taxonomías de áreas en el pirineo catalán: Aproximación metodológica al análisis de variables socioterritoriales. Geofocus Revista Internacional de Ciencia y Tecnología de la Información Geográfica 2004, 4, 209–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Carrión, J.J. Manual de análisis estadístico de los datos; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, S. Aproximación a la estadística desde Ciencias Sociales; Universidad de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K., LIII. On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1901, 2, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Nguyen, T.V.T.; Sahito, N. Role of Urban Public Space and the Surrounding Environment in Promoting Sustainable Development from the Lens of Social Media. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standar, A.; Kozera, A. The Role of Local Finance in Overcoming Socioeconomic Inequalities in Polish Rural Areas. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Mejía, M.; Alvarado, S.V.; Miranda, J.C. Conflicto armado, variables socio-económicas y formación ciudadana: Un análisis de impacto. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, niñez y juventud 2016, 14, 147–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Martín, J.M.; Sánchez Rivero, M.; Rengifo Gallego, J.I. La evaluación del potencial para el desarrollo del turismo rural. Aplicación metodológica sobre la provincia de Cáceres 2013, 13, 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, J.M.S.; Rivas, J.C.J.; Claver, M.M.G.; Martín, M.N.P. Detección de áreas óptimas para la implantación de alojamientos rurales en Extremadura: Una aplicación sig. Lurralde: Investigación y espacio 1999, 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C. Perspectives on cultural and sustainable rural tourism in a smart region: The case study of Marmilla in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2015, 7, 6412–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Rubio, J.A.; Garcia Garcia, Y. Turismo Rural en Extremadura. El caso del Turismo Paisano. Revista Española de Estudios Agrosociales y Pesqueros 2005, 206, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-A Sustainable development factor for improving the ‘health’of rural settlements. Case study Apuseni mountains area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F.-J. Rural tourism: Development, management and sustainability in rural establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Martín, J.M.; Salinas Fernández, J.A.; Rodríguez Martín, J.A.; Jiménez Aguilera, J.D.D. Assessment of the tourism’s potential as a sustainable development instrument in terms of annual stability: Application to Spanish rural destinations in process of consolidation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I.; Blas-Morato, R. Hot spot analysis versus cluster and outlier analysis: An enquiry into the grouping of rural accommodation in Extremadura (Spain). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Gurría-Gascón, J.-L.; García-Berzosa, M.-J. The cultural heritage and the shaping of tourist itineraries in rural areas: The case of historical ensembles of Extremadura, Spain. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E.R.; Gisbert, F.J.G.; Martí, I.C. Delimitación de Áreas Rurales y Urbanas a Nivel Local: Demografía, Coberturas del Suelo y Accesibilidad; Fundacion BBVA: Bilbao, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, B.B. El turismo rural en Galicia. Análisis de su evolución en la última década. Cuadernos de turismo 2006, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Saladié, Ò.; Gutiérrez, A.; Clavé, S.A. Influencia de la alta velocidad ferroviaria en la elección del destino turístico según el origen de los viajeros. El caso de la Costa Dorada en Cataluña. Documents d’anàlisi geogràfica 2018, 64, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soukiazis, E.; Proença, S. Tourism as an alternative source of regional growth in Portugal: A panel data analysis at NUTS II and III levels. Port. Econ. J. 2008, 7, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.; Lagar, D.; García, R. El geoturismo como estrategia de desarrollo en áreas deprimidas: Propuesta del Geoparque Villuercas, Ibores, Jara (Extremadura). Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españones 2011, 56, 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G.; Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Ríos Rodríguez, N. Análisis espacial de la oferta y demanda de alojamientos turísticos de Extremadura. In Desafíos y oportunidades de un mundo en transición; una interpretación desde la Geografía; Universidad de Valencia y Asociación Española de Geografía; Servei de Publicacions: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, A.; Neto, P.; Serrano, M.M. A long-term mortality analysis of subsidized firms in rural areas: An empirical study in the Portuguese Alentejo region. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.M.C.; Sáez, A.M.; Díaz, A.C. Perfiles turísticos en una muestra de sujetos españoles: Un modelo de segmentación empírica en función de los patrones de viaje y las características del viajero. Estud. Turísticos 2007, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mateos, H.S.M. La accesibilidad regional y el efecto territorial de las infraestructuras de transporte. Aplicación en Castilla-La Mancha. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2012, 59, 79–103. [Google Scholar]

| Tourist Territories | Municipalities | Population 2018 | Population Growth (2010–2018) (%) | Surface (Km2) | Density of Population (Km2) | Index Old Age * | Index of Youth ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara | 19 | 12,885 | −11.00 | 2546.8 | 5.06 | 33.16 | 9.19 |

| Reserva de la Biosfera de Monfragüe | 30 | 46,893 | −3.08 | 2714.71 | 16.64 | 18.80 | 15.46 |

| Sierra de Gata, Las Hurdes, Valle del Alagón | 53 | 63,963 | −7.19 | 3516.2 | 18.19 | 26.34 | 11.84 |

| Tajo Internacional, Sierra de San Pedro | 27 | 49,676 | −8.63 | 4733.0 | 10.50 | 25.42 | 11.67 |

| Trujillo, Miajadas, Montánchez | 42 | 48,610 | −7.78 | 3318.03 | 15.31 | 25.83 | 11.17 |

| Valle del Ambroz, Tierras de Granadilla | 23 | 16,610 | −4.90 | 942.8 | 17.62 | 30.18 | 10.28 |

| Valle del Jerte, La Vera | 30 | 34,984 | −6.37 | 1258.6 | 27.80 | 25.39 | 11.48 |

| Total | 224 | 273,621 | −6.99 | 19,030.1 | 14.41 | 26.45 | 11.58 |

| Variables |

|---|

| Total travelers per 1000 inhabitants (TTravel) |

| Total overnight stays per 1000 inhabitants (TOverNight) |

| Total accommodation places per 1000 inhabitants (TAcom) |

| Total hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (THotel) |

| Total rural places per 1000 inhabitants (TRural) |

| Total non-hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (TNonhot) |

| Natural growth rate (2010–2018) (NatGrowth) |

| Aging rate (2010–2018) (AgingR) |

| Population growth rate (2010–2018) (PopGrowth) |

| Migration rate (2010–2018) (MigrationR) |

| Average income per capita (2018) (AverIncome) |

| Unemployment rate (2018) (UnemployR) |

| Assets of Cultural Interest per 1000 inhabitants (AssetsCuturalI) |

| Natural Protected Areas (%) (NatProtecA) |

| Correlations | TTravel | TOverNight | TAcom | THotel | TRural | TNonhot | NatGrowth | AgingR | PopGrowth | MigrationR | AverIncome | UnemployR | AssetsCuturalI | NatProtecA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTravel | 1 | 0.98 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.13 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.14 | −0.55 | −0.70 | 0.11 |

| TOverNight | 0.98 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.18 | −0.57 | −0.62 | 0.19 |

| TAcom | 0.94 | 0.92 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.04 | −0.79 | −0.60 | 0.24 |

| THotel | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.40 | −0.50 | 0.92 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.01 | −0.73 | −0.21 |

| TRural | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.02 | −0.15 | −0.89 | −0.44 | 0.27 |

| TNonhot | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.88 | 1 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.09 | −0.82 | −0.53 | 0.30 |

| NatGrowth | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.29 | −0.50 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 1 | −0.53 | 0.58 | −0.39 | 0.32 | −0.49 | 0.01 | 0.53 |

| AgingR | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.92 | 0.29 | 0.31 | −0.53 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.73 | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.62 | −0.43 |

| PopGrowth | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.76 | −0.11 | −0.60 | 0.29 |

| MigrationR | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.24 | −0.39 | 0.73 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.31 | −0.66 | −0.20 |

| AverIncome | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.14 | -0.15 | 0.09 | 0.32 | −0.12 | 0.76 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.30 | −0.40 | 0.41 |

| UnemployR | −0.55 | −0.57 | −0.79 | 0.01 | −0.89 | −0.82 | −0.49 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.12 | −0.33 |

| AssetsCuturalI | −0.70 | −0.62 | −0.60 | −0.73 | −0.44 | −0.53 | 0.01 | −0.62 | −0.60 | −0.66 | −0.40 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.29 |

| NatProtecA | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.24 | −0.21 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.53 | −0.43 | 0.29 | −0.20 | 0.41 | −0.33 | 0.29 | 1 |

| Variables | Initial | Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Total accommodation places per 1000 inhabitants (TAcom) | 1 | 0.997 |

| Total non-hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (TNonhot) | 1 | 0.989 |

| Total travelers per 1000 inhabitants (TTravel) | 1 | 0.985 |

| Unemployment rate (2018) (UnemployR) | 1 | 0.982 |

| Total overnight stays per 1000 inhabitants (TOverNight) | 1 | 0.94 |

| Population growth rate (2010–2018) (PopGrowth) | 1 | 0.94 |

| Total rural places per 1000 inhabitants (TRural) | 1 | 0.927 |

| Aging rate (2010–2018) (AgingR) | 1 | 0.927 |

| Average income per capita (2018) (AverIncome) | 1 | 0.927 |

| Total hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (THotel) | 1 | 0.926 |

| Migration rate (2010–2018) (MigrationR) | 1 | 0.925 |

| Natural growth rate (2010–2018) (NatGrowth) | 1 | 0.874 |

| Assets of Cultural Interest per 1000 inhabitants (AssetsCuturalI) | 1 | 0.757 |

| Natural Protected Areas (%) (NatProtecA) | 1 | 0.587 |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | % Accumulated | |

| 1 | 6.869 | 49.065 | 49.065 |

| 2 | 3.484 | 24.886 | 73.951 |

| 3 | 2.329 | 16.634 | 90.586 |

| 4 | 0.751 | 5.367 | 95.953 |

| 5 | 0.413 | 2.948 | 98.901 |

| 6 | 0.154 | 1.099 | 100.000 |

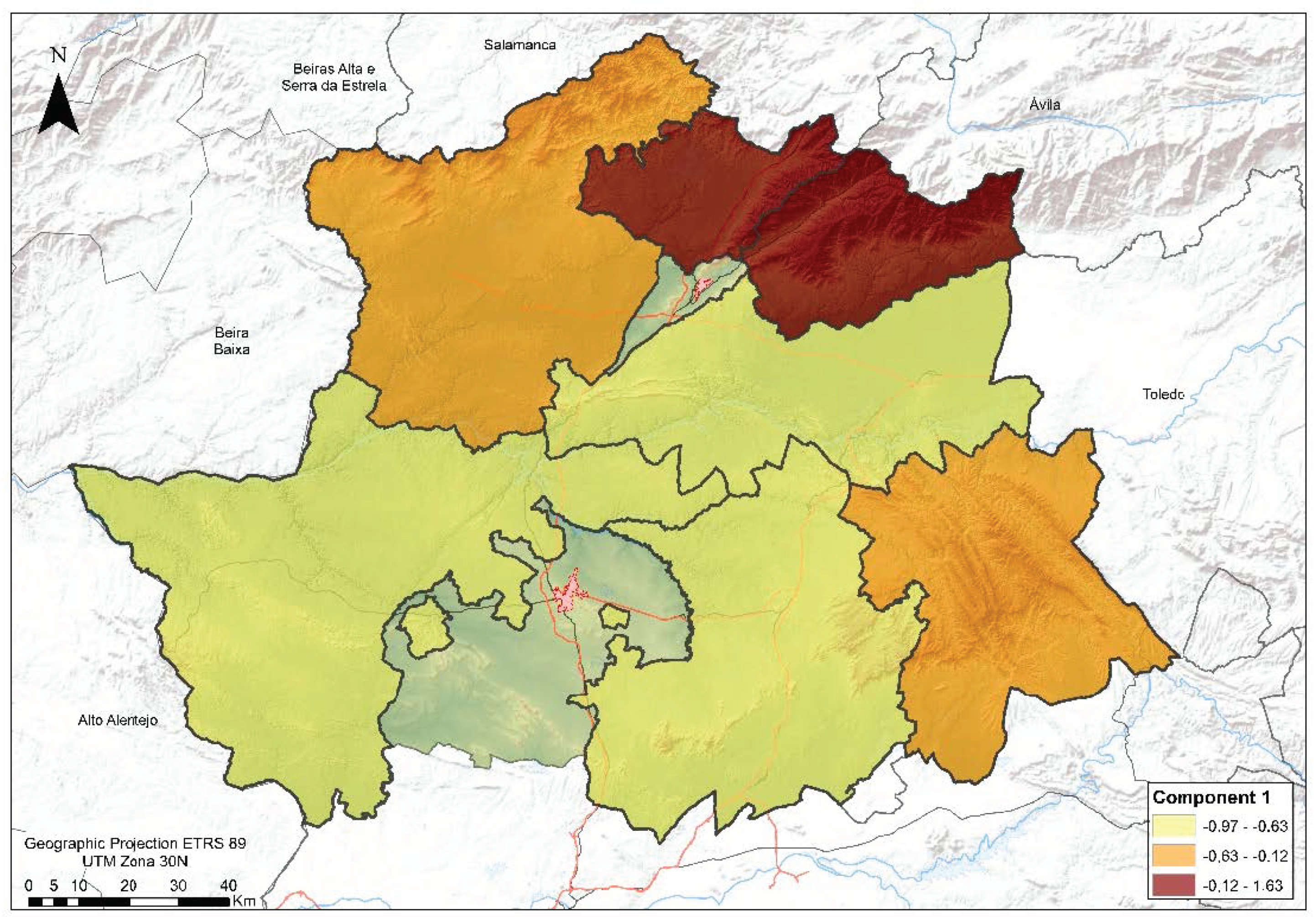

| Variables | Component 1 |

|---|---|

| Total travelers per 1000 inhabitants (TTravel) | 0989 |

| Total overnight stays per 1000 inhabitants (TOverNight) | 0967 |

| Total accommodation places per 1000 inhabitants (TAcom) | 0949 |

| Total non-hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (TNonhot) | 0921 |

| Total rural places per 1000 inhabitants (TRural) | 0788 |

| Total hotel beds per 1000 inhabitants (THotel) | 0706 |

| Population growth rate (2010–2018) (PopGrowth) | 0642 |

| Aging rate (2010–2018) (AgingR) | 0597 |

| Migration rate (2010–2018) (MigrationR) | 0559 |

| Average income per capita (2018) (AverIncome) | 0229 |

| Natural growth rate (2010–2018) (NatGrowth) | 0199 |

| Natural Protected Areas (%) (NatProtecA) | 0145 |

| Unemployment rate (2018) (UnemployR) | −0565 |

| Assets of Cultural Interest per 1000 inhabitants (AssetsCuturalI) | −0758 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nieto Masot, A.; Ríos Rodríguez, N. Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2021, 13, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010239

Nieto Masot A, Ríos Rodríguez N. Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010239

Chicago/Turabian StyleNieto Masot, Ana, and Nerea Ríos Rodríguez. 2021. "Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain)" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010239

APA StyleNieto Masot, A., & Ríos Rodríguez, N. (2021). Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability, 13(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010239