Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context

1.2. Authenticity in Heritage Conservation

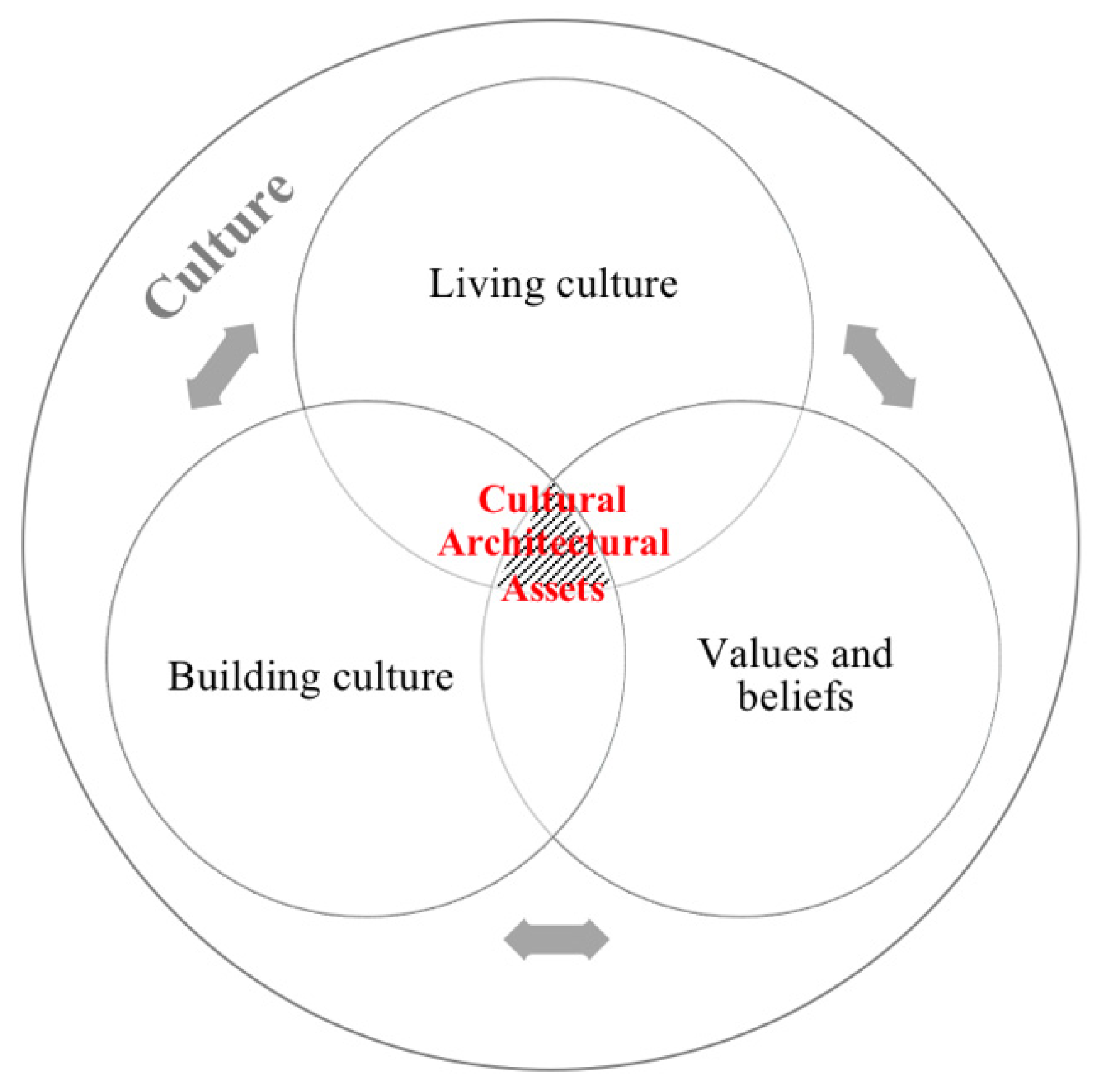

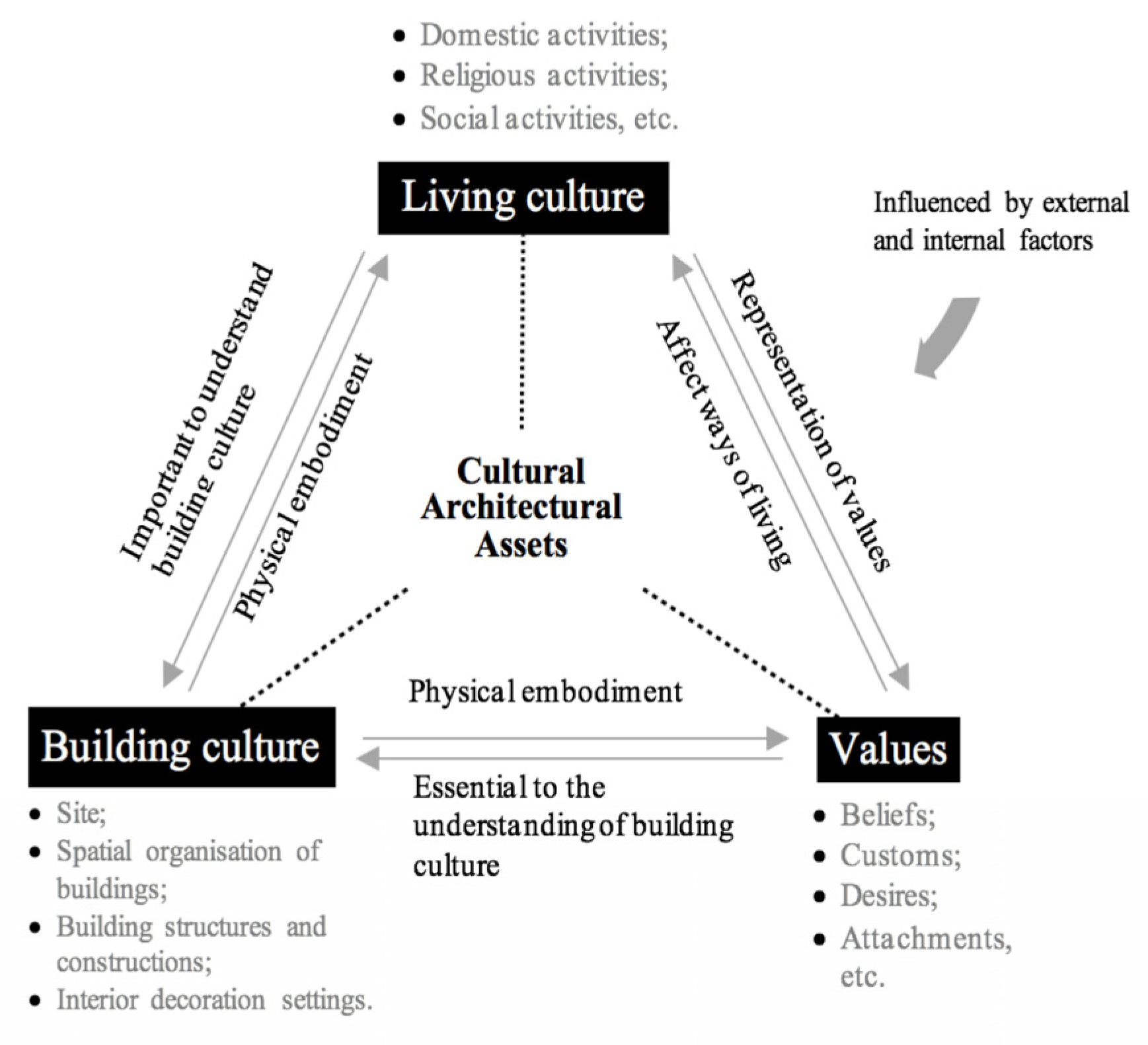

1.3. Key Concept: Cultural Architectural Assets

2. Methodology and Data Collection

2.1. An Integrative Anthropological and Architectural Approach

2.2. Fieldwork in Yongning Region

2.3. Methods Used in the Research

2.3.1. Participatory Observations

2.3.2. Photographic Survey

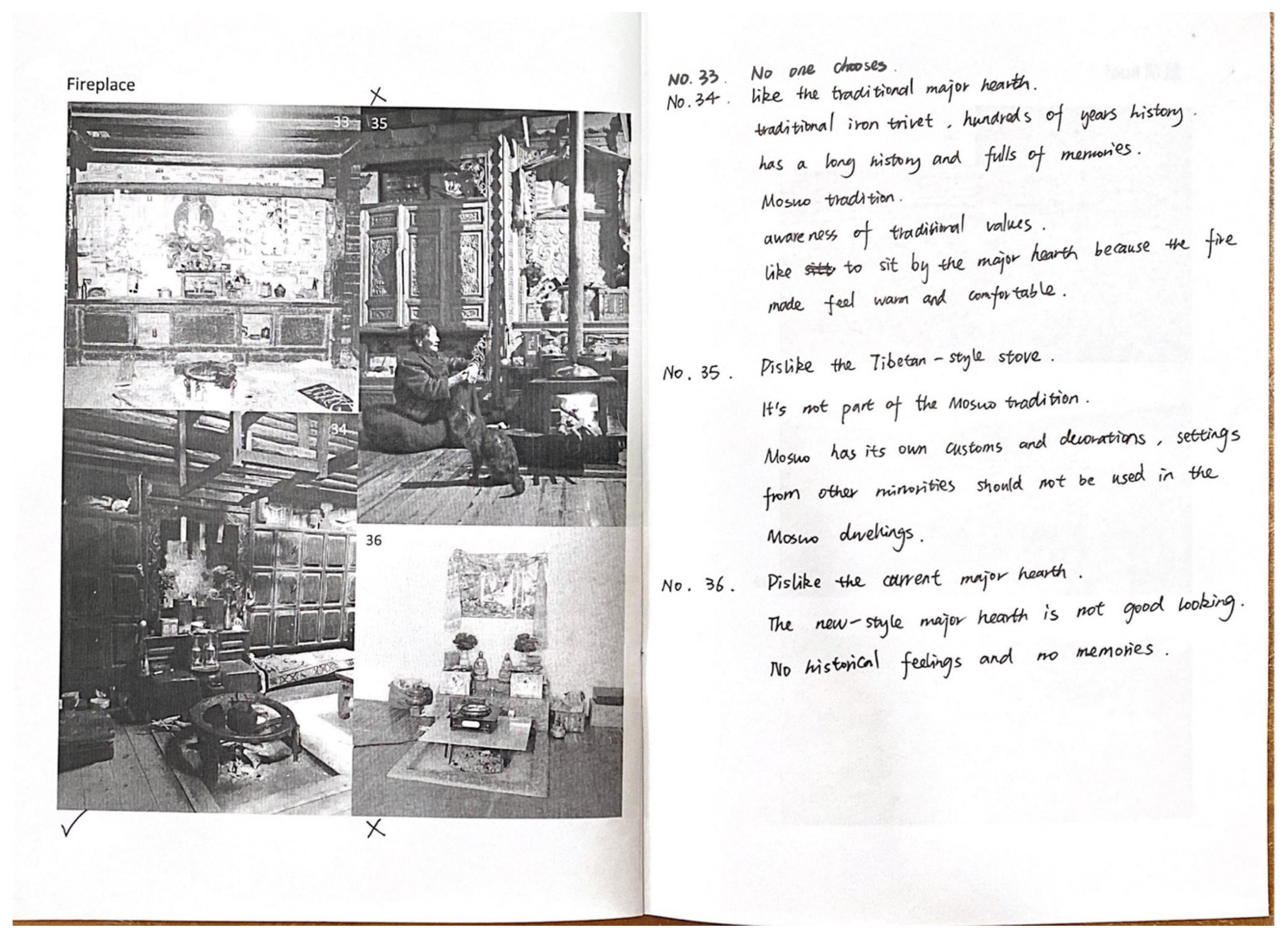

2.3.3. Photo Elicitation Interviews

3. Results and Discussion

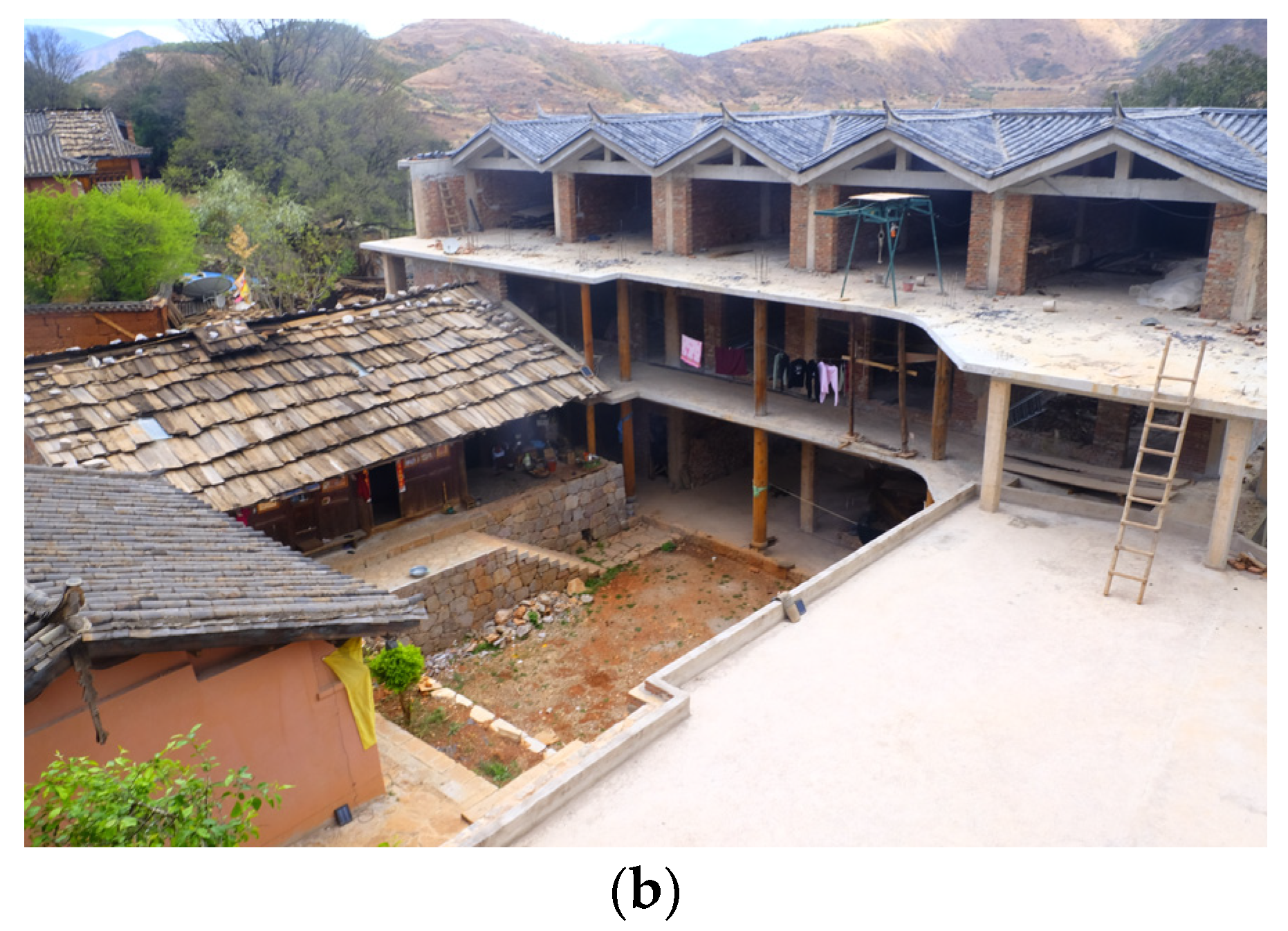

3.1. Changes in the Mosuo Dwellings

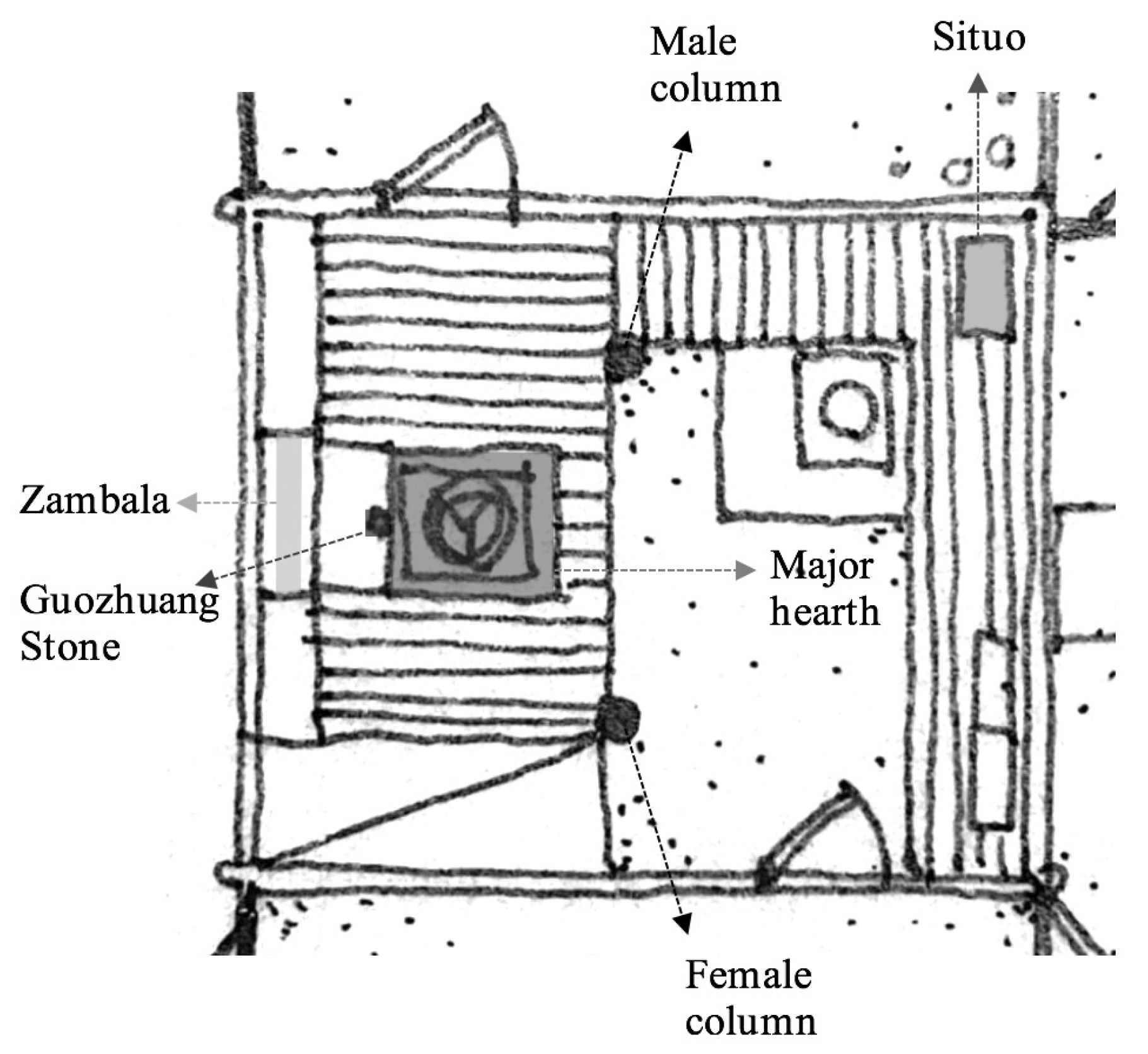

3.2. Continuities in the Mosuo Dwellings

3.3. Interpretation of Authenticity in Transitions

- Living culture—relating to physical interaction and use of architecture, e.g., domestic activities;

- Building culture—physical aspects, including site, spatial organisation of buildings, building structures and constructions, and interior decoration settings;

- Values—relating to human cultural values, beliefs, customs, desires and attachments.

3.4. Sustainable Conservation Responding to Dynamic Authenticity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ninglang Yizu Zizhixian Zhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui (Compiling Committee of Ninglang Yi Autonomous County). Ninglang Yizu Zizhixian Zhi (Ninglang Yi Autonomous County Local Records); Yunnan Nationalities Publishing House: Yunnan, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- The Lugu Lake Mosuo Cultural Development Association. Matriarchal/Matrilineal Culture. Available online: http://www.mosuoproject.org/matri.html (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- Walsh, E.R. The Mosuo—Beyond the Myths of Matriarchy: Gender Transformation and Economic Development. Ph.D. Thesis, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Discovering the Mysterious Oriental Kingdom of the Female; Yunnan Nationalities Press: Kunming, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, X. Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.K. Mortuary Rituals and Symbols among the Moso. In Naxi and Moso Ethnography. Kin, Rites, Pictographs; Oppitz, M., Hsu, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Zurich, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Bai, Y.; Che, Z. You Jingshen Yiyi de Juzhu Kongjian Mosuo Minju de Jianzhu Xingtai he Juzhu Wenhua (Residential Space Containing Spirit Contents: Architectural Form and Residential Culture of Mosuo Folk Houses). Huazhong Archit. 2009, 3, 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, R.; Song, Z. Yongning Naxizu de muxi Zhidu (The Matrilineal System of the Naxi People at Yongning); Yunnan People’s Publishing House: Yunnan, China, 1983; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, C.K. The Yongning Moso: Sexual Union, Household Organization, Gender and Ethnicity in a Matrilineal Duolocal Society in Southwest China. Ph.D. Thesis, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Hustvedt, A. A Society without Fathers or Husbands: The Na of China; Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, K.; Ma, W.; Sun, N.; Luo, D. Xinan Minju (Chinese Vernacular House of Southwest China); Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z. Shengcun he Wenhua de Xuanze: Mosuo Muxizhi ji Xiandai Bianqian (A Choice between Survival and Culture: Mosuo Matriarchal Culture and Modern Change); Education Publishing House: Yunnan, China, 2000; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.Z. Zhongguo Minju Yanjiu (Research on Chinese dwellings); China Architecture Publishing: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.Z. Zhongguo Zhuzhai Gaishuo (Chinese Traditional Residence); Architectural Engineering Press: Beijing, China, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Rudofsky, B. Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture; University of USA New Mexico Press: Bernalillo, NM, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L.H. Houses and House Life of the American Aborigines; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, N. The Mother House: The Symbolism and Practices of Gender among the Naxi in Southwest China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson, R. The Living House: An Anthropology of Architecture in South-East Asia; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X. Research on the Building Paradigm of Naxi Vernacular architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Pitts, A. Sustainable Building Practice and Guidance for Dai Villages, Southwest China. In Proceedings of the PLEA (Passive and Low Energy Architecture) Conference 2018: Smart and Healthy within the 2-Degree Limit, Hong Kong, China, 10–12 December 2018; pp. 1103–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s Traditional Rural Architecture: A Cultural Geography of the Common House; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q. The wooden house by the Lugu Lake (Qicai Yunnan zhi Shijiu Luguhu bian de Mulengfang). ID+C Inter. Des. Constr. 2001, 12, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, F. Mosuo Yishu (Mosuo Art); Sichuan Fine Arts Press: Chengdu, China, 2005; pp. 72–103. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhad, S.F.; Eshrati, P.; Eshrati, D. A Definition of Authenticity Concept in Conservation of Cultural Landscapes. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet-IJAR 2015, 9, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulukan, M.; Arslan, H. Developing a New Authenticity Rating System on Architectural Conservation. Sustain. City 2012, 2, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Assi, E. Searching for the Concept of Authenticity: Implementation Guidelines. J. Archit. Conserv. 2000, 6, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/charters.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/convention-en.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Operational Guidelines for the World Heritage Committee. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide77a.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- The Nara Document on Authenticity. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide05-en.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tylor, E.B. Primitive Culture; Peter Smith Publisher: Gloucester, MA, USA, 1871. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Dwellings: The House Across the World; Phaidon: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, B. A Scientific Theory of Culture; Chapel Hill, The University of North Carolina Press: New York, NY, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Culture, Architecture, and Design; Locke Science Pub. Co.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Thirty-Three Papers in Environment Behaviour Research; Urban International Press: Newcastle, UK, 1995; pp. 399–436. [Google Scholar]

- Karakul, Ö. Folk Architecture in Historic Environments: Living Spaces for Intangible Cultural Heritage. Milli Folklor Int. Q. J. Cult. Stud. 2007, 19, 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Cultural Traits and Environmental Contexts-Problems of Cultural Specificity and Cross-Cultural Comparability. In Proceedings of the International Symposium Culture and Space in the Home Environment, Critical Evaluations and New Paradigms, ITU, Faculty of Architecture in Collaboration with IAPS, Istanbul, Turkey, 4–7 June 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karakul, Ö. A Holistic Approach to Historic Environments: Integrating Tangible and Intangible Values; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2013; pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Chemers, M.M. Culture and Environment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, S.F. Cultural Influences on Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX, USA, 1994; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Oranratmanee, R. Rural Homestay: Interrelations between Space, Social Interaction and Meaning in Northern Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga, M. A Conversation with Architects: Paul Oliver and the Anthropology of Shelter. Archit. Theory Rev. 2017, 21, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, D.M. Ethnography: Step-by-Step; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Bureau of Ninglang County. Ninglang Yi Autonomous County Local Records (Ninglang Yizu Zizhixian Zhi); Yunnan Nationalities Publishing House: Yunnan, China, 2003.

- Walsh, E.R. From Nü Guo to Nü’er Guo: Negotiating desire in the land of the Mosuo. Mod. Chin. 2005, 31, 448–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J. Qualitative Researching, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, D. Visual ethnography: Using photography in qualitative research. Q. Sociol. 1989, 12, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.E. Auto-Photography; The Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D. Talking about Pictures: A Case for Photo Elicitation. Vis. Stud. 2002, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, C.K. Quest for Harmony: The Moso Traditions of Sexual Union and Family Life; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, C. Architecture and Identity: Responses to Cultural and Technological Change, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Are World Heritage Concepts of Integrity and Authenticity Lacking in Dynamism? A Critical Approach to Mediterranean Autotopic Landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2018, 6, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Esparza, J. Clarifying Dynamic Authenticity in Cultural Heritage. A Look at Vernacular Built Environments. ICOMOS Univ. Forum 2018, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, T.M. Pilgrimage, Devotional Practices and the Consumption of Sacred Places in Ancient Egypt and Contemporary Syria. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.W. Wenhua Yichan Baohu de Xing yu Shen Cong Shaxi Fuxing Gongcheng Shijian Fansi Baohu yu Fazhan de Guanxi (Cultural Heritage Conservation: Reflection on the Relationship between Conservation and Development from Shaxi Rehabilitation Project). Archit. J. 2012, 6, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Idilfitri, S. Understanding the Significance of Cultural Attribution. Anthropology 2016, 4, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.Z. Chuantong Minju Jiazhi yu Chuancheng (The Value and Inheritance of Traditional Dwellings); China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Asquith, L.; Vellinga, M. Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century: Theory, Education, and Practice; Taylor & Francis: Oxon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, R.L.H. Sustainability. In International Encyclopedia of Housing and Home; Smith, S.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vellinga, M. Vernacular architecture and sustainability: Two or three lessons. In Vernacular Architecture: Towards a Sustainable Future; Mileto, C., García Soriano, L., Vegas, F., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, M. Sustainability and Vernacular Architecture: Rethinking What Identity Is’. In Urban and Architectural Heritage Conservation within Sustainability; Hmood, K., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. Ethnic Heritage in Yunnan: Contradictions and Challenges. In Reconsidering Cultural Heritage in East Asia; Matsuda, A., Mengoni, L.E., Eds.; Ubiquity Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. Some Problems in the Development of the Tourism in Yunnan. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2004, 3, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P. Re-presenting and Representing the Vernacular: The Open-air Museum. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 1998, 10, 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Can, Ş.G. A Critical Assesment for Reuse of Traditional Dwellings as “Boutique Hotels” in Urgup. Master’s Dissertation, METU, Ankara, Turkey, 2007. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Conservation of Vernacular Buildings. Available online: http://www.bjchp.org (accessed on 26 April 2019).

- Resolutions on the Regeneration of Historic Urban Sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/publications/93towns7.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/2145/ (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Feilden, B.M. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. On Defining the Cultural Heritage. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2000, 49, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.phpURL_ID=17716&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe: Granada. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168007a087 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Mounir, B. The Interdependency of the Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 14th ICOMOS General Assembly and Scientific Symposium, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, F. Conservation and Rehabilitation of Urban Heritage in Developing Countries. Habitat Int. 1996, 20, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, M. City Architecture as Cultural Ingredient. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 149, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age Range | Past Ways of Living | Current Ways of Living | Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 18 years old | Light farming work; playing on the ground in the yard | Go to school to learn knowledge, some studying in cities and some studying in nearby villages’ school | More access to official education; influence of outside areas, such as language |

| 18–30 years old | Traditional farming work and housework maintenance; traditional rites and festivals | Some starting to work in nearby villages, and some running their businesses, some working in cities; a few performing farming activities; watching TV for entertainment in the living room | Not many traditional farming activities performed; modern entertainment involved in watching TV; the variety of work increased |

| 30–60 years old | Traditional farming work and housework maintenance; traditional rites and festivals | Some starting to work in nearby villages, and some running their businesses, some working in cities, performing farming activities; traditional rites and festivals; watching TV for entertainment in the living room | Few farming activities performed; modern entertainment involved in watching TV; the variety of work increased |

| over 60 years old | Less physically active, light farming work and housework maintenance; religious pray | Less physically active, light farming work and housework maintenance; religious pray | No change |

| Traditional Dwellings | Transforming Dwellings | |

|---|---|---|

| Site selection |

|

|

| Spatial organisation |

|

|

| Architectural structure and materials |

|

|

| Interior settings and decoration |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, H.; Xiao, J. Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010143

Feng H, Xiao J. Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Huichao, and Jieling Xiao. 2021. "Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010143

APA StyleFeng, H., & Xiao, J. (2021). Dynamic Authenticity: Understanding and Conserving Mosuo Dwellings in China in Transitions. Sustainability, 13(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010143