The Effects of Expected Benefits on Image, Desire, and Behavioral Intentions in the Field of Drone Food Delivery Services after the Outbreak of COVID-19

Abstract

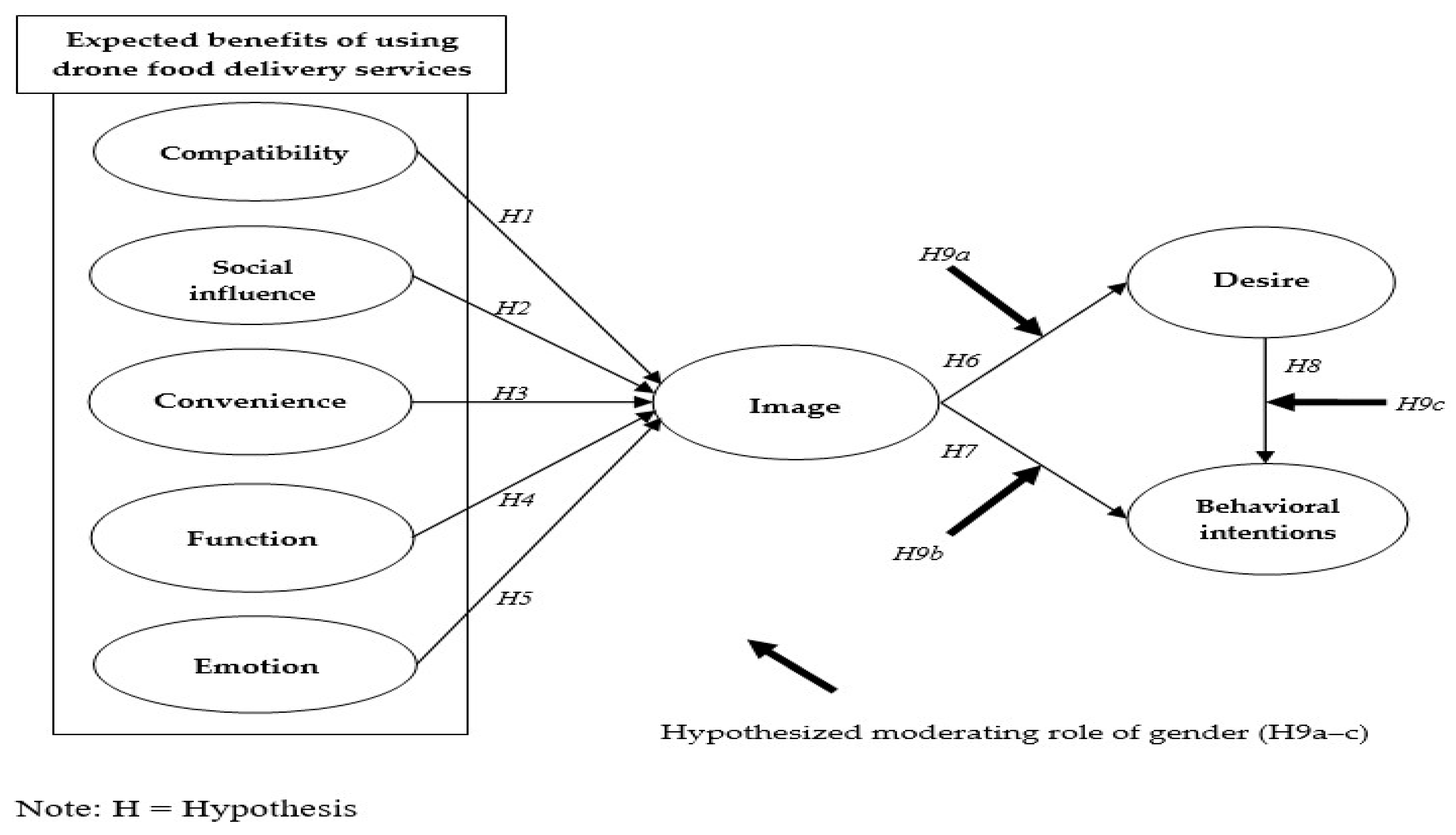

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Expected Benefits

2.2. Effect of Expected Benefits on Image

2.3. Effect of Image on Desire and Behavioral Intentions

2.4. Effect of Desire on Behavioral Intentions

2.5. The Moderating Role of Gender

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.2. Data Collection

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Demographic Profile of Respondents

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

4.4. The Moderating Role of Gender

5. Discussions and Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Worldometers. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- The Guardian. Anger as Italy Slowly Emerges from Long COVID-19 Lockdown. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/03/anger-as-italy-slowly-emerges-from-long-covid-19-lockdown (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- National Restaurant Association. The Restaurant Industry Impact Survey. Available online: https://www.restaurant.org/manage-my-restaurant/business-operations/covid19/research/industry-research (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Southey, F. Online Food Delivery ‘One of the Only Winners’ in Coronavirus Outbreak. Available online: https://www.foodnavigator.com/Article/2020/03/19/Online-food-delivery-one-of-the-only-winners-in-coronavirus-outbreak (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Dronethusiast. The History of Drones (Drone History Timeline From 1849 to 2018). Available online: https://www.dronethusiast.com/history-of-drones/ (accessed on 1 December 2018).

- Patrikar, J.; Moon, B.G.; Scherer, S. Wind and the City: Utilizing UAV-Based In-Situ Measurements for Estimating Urban Wind Fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanyam, A.; Patil, A.K.; Chai, Y.H. GazeGuide: An Eye-Gaze-Guided Active Immersive UAV Camera. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar]

- Bonatti, R.; Wang, W.; Ho, C.; Ahuja, A.; Gschwindt, M.; Camci, E.; Kayacan, E.; Choudhury, S.; Scherer, S. Autonomous aerial cinematography in unstructured environments with learned artistic decision-making. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 606–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.K.; Chai, Y.H. On-Site 4-in-1 Alignment: Visualization and Interactive CAD Model Retrofitting Using UAV, LiDAR’s Point Cloud Data, and Video. Sensors 2019, 19, 3908. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, W. Investigating motivated consumer innovativeness in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, H. Perceived innovativeness of drone food delivery services and its impacts on attitude and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 81, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J. Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, H. Consequences of a green image of drone food delivery services: The moderating role of gender and age. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNBC. Domino’s Delivers World’s First Ever Pizza by Drone. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2016/11/16/dominos-has-delivered-the-worlds-first-ever-pizza-by-drone-to-a-new-zealand-couple.html (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Yonhap News. Seoul Tests Drone Food Delivery Service Amid Pandemic. Available online: https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20200919003300320 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Ivanov, S.; Webster, C.; Garenko, A. Young Russian adults’ attitudes towards the potential use of robots in hotels. Technol. Soc. 2018, 55, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, W. Consequences of psychological benefits of using eco-friendly services in the context of drone food delivery services. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y.J. Exploring perceived risk in building successful drone food delivery services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3249–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.J.; Sial, M.S. Application of internal environmental locus of control to the context of eco-friendly drone food delivery services. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Moderating effect of age and gender on consumer style inventory in predicting Indian consumers’ local retailer loyalty. Int. Rev. Retail, Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyesnikova, N.; Dodd, T.H.; Wilcox, J.B. Gender as a moderator of reciprocal consumer behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Makens, J.C. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 4th ed; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Tang, L.; Fiore, A.M. Enhancing consumer–brand relationships on restaurant Facebook fan pages: Maximizing consumer benefits and increasing active participation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Woo, E.; Uysal, M. Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.R.; Lall, A.; Mane, T. Extending the TAM Model: Intention of Management Students to Use Mobile Banking: Evidence from India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Jeong, M.; Baloglu, S. Tourists’ adoption of self-service technologies at resort hotels. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukusta, D.; Heung, V.C.; Hui, S. Deploying self-service technology in luxury hotel brands: Perceptions of business travelers. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K. Traveler acceptance of an app-based mobile tour guide. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 401–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mao, Z.; Wang, M.; Hu, L. Goodbye maps, hello apps? Exploring the influential determinants of travel app adoption. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 1059–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Hajiyev, J.; Su, C.R. Examining the students’ behavioral intention to use e-learning in Azerbaijan? The general extended technology acceptance model for e-learning approach. Comput. Educ. 2017, 111, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.S.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S.; Kim, W. Role of airline food quality, price reasonableness, image, satisfaction, and attachment in building re-flying intention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. Relationships among green image, consumer attitudes, desire, and customer citizenship behavior in the airline industry. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwata, B.; Lawsb, E.; Maunchonthama, R.; Rattanaphinanchaia, S.; Muttamaraa, S.; Moutona, K.; Lina, Y.; Suksaia, C. Resilience to crises of Thai MICE stakeholders: A longitudinal study of the destination image of Thailand as a MICE destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 100704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryadana, M.L. Destination Attributes–Its Role on Constructing Image of Bandung as A MICE Destination in Indonesia. Kontigensi: Sci. J. Manag. 2018, 6, 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Kim, W. Traveler loyalty and its antecedents in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 474–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.K.W. Hotel image and reputation on building customer loyalty: An empirical study in Macau. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y. How to enhance the image of edible insect restaurants: Focusing on perceived risk theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Song, H.; Youn, H. The chain of effects from authenticity cues to purchase intention: The role of emotions and restaurant image. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Hoz-Correa, A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. The role of information sources and image on the intention to visit a medical tourism destination: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Huang, Y.C. An integrated structural model examining the relationships between natural capital, tourism image and risk impact and behavioural intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1357–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, R.; Pisharodi, R.M. Facets of country of origin image: An empirical assessment. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C. An empirical study of the effects of service quality, perceived value, corporate image, and customer satisfaction on behavioral intentions in the Taiwan quick service restaurant industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 14, 364–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Baek, H.; Lee, K.; Huh, B. Perceived benefits, attitude, image, desire, and intention in virtual golf leisure. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2014, 23, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choi, J.K. An investigation of passengers’ psychological benefits from green brands in an environmentally friendly airline context: The moderating role of gender. Sustainability 2018, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The distinction between desires and intentions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Wang, Y.; Gil, S.M. The influence of a film on destination image and the desire to travel: A cross-cultural comparison. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Kaplanidou, K. Destination personality, affective image, and behavioral intentions in domestic urban tourism. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the relationships between tourists’ emotional experiences, perceived overall image, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, W. Antecedents of green loyalty in the cruise industry: Sustainable development and environmental management. Business Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqih, K.M.; Jaradat, M.I.R.M. Assessing the moderating effect of gender differences and individualism-collectivism at individual-level on the adoption of mobile commerce technology: TAM3 perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 22, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Bike-traveling as a growing phenomenon: Role of attributes, value, satisfaction, desire, and gender in developing loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, F.A.; McNeilly, K.M. Links among satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intentions: The moderating effect of experience, gender, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 34, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, M.K. Women in the information technology profession: A literature review, synthesis and research agenda. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, R.; Gavin, J.; Brosnan, M.; Cromby, J.; Gregory, H.; Guiller, J.; Maras, P.; Moon, A. Gender, internet experience, internet identification, and internet anxiety: A ten-year followup. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, X.; Fan, W.; Gordon, M. The joint moderating role of trust propensity and gender on consumers’ online shopping behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Personality, satisfaction, image, ambience, and loyalty: Testing their relationships in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yoon, H.J. Hotel customers’ environmentally responsible behavioral intention: Impact of key constructs on decision in green consumerism. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Wang, S.H. User acceptance of mobile internet based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: Investigating the determinants and gender differences. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2010, 38, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEWSIS. Government, Drone Industry Foundation… “Five Major Powers in the World”. Available online: http://www.newsis.com/view/?id=NISX20171228_0000188628&cID=13001&pID=13000 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Yogiyo. Korea’s Very First Official Drone Food Delivery Test. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BxAqGSgs1Y (accessed on 16 October 2020).

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 177 | 51.6 |

| Female | 166 | 48.4 |

| Age | ||

| 20s (a person aged between 20 and 29 years) | 103 | 30.0 |

| 30s (a person aged between 30 and 39 years) | 107 | 31.3 |

| 40s (a person aged between 40 and 49 years) | 102 | 29.7 |

| 50s (a person aged between 50 and 59 years) | 31 | 9.0 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than a high school diploma | 30 | 8.7 |

| Associate’s degree | 43 | 12.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 226 | 65.9 |

| Graduate degree | 44 | 12.8 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| 6001 $ US and over | 21 | 6.1 |

| 5001 $ US–6000 $ US | 10 | 2.9 |

| 4001 $ US–5000 $ US | 30 | 8.7 |

| 3001 $ US–4000 $ US | 49 | 14.3 |

| 2001 $ US–3000 $ US | 97 | 28.3 |

| 1001 $ US–2000 $ US | 67 | 19.5 |

| Under 1000 $ US | 69 | 20.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 198 | 57.7 |

| Married | 141 | 41.1 |

| Widowed/Divorced | 4 | 1.2 |

| Construct and Scale Item | Standardized Loading a |

|---|---|

| Compatibility | |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to fit my lifestyle. | 0.897 |

| Using drone food delivery services would fit well with how I like to order | 0.938 |

| Drone food delivery services are likely to be suitable when ordering food. | 0.878 |

| Social influence | |

| If I use drone food delivery services, I could impress others. | 0.822 |

| If I use drone food delivery services, I could show that I am an early adopter. | 0.950 |

| If I use drone food delivery services, I could show my image that seems to lead the trend to others. | 0.843 |

| Convenience | |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to be easy to use. | 0.702 |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to order food anywhere. | 0.719 |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to save time. | 0.852 |

| Function | |

| Drone food delivery services do not seem to lead to food delivery problems. | 0.846 |

| Drone food delivery services seem to perform satisfactorily. | 0.855 |

| Using drone food delivery services to order food would be safe. | 0.919 |

| Emotion | |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to be fun. | 0.848 |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to bring enjoyment. | 0.966 |

| Using drone food delivery services seems to make me happy. | 0.757 |

| Image | |

| Overall image for using drone food delivery services is good. | 0.935 |

| Overall image I have about drone food delivery services is great. | 0.953 |

| Overall, I have a good image about drone food delivery services. | 0.947 |

| Desire | |

| I desire to use drone food delivery services when ordering food. | 0.946 |

| My desire of using drone food delivery services when ordering food is strong. | 0.962 |

| I want to use drone food delivery services when ordering food. | 0.956 |

| Behavioral intentions | |

| I will use drone food delivery services when ordering food. | 0.846 |

| I am willing to use drone food delivery services when ordering food. | 0.939 |

| I am likely to use drone food delivery services when ordering food. | 0.938 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 581.546, df = 224, χ2/df = 2.596, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.937, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.951, and RMSEA = 0.068 | |

| Mean (SD) | AVE | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Compatibility | 3.86 (1.27) | 0.818 | 0.931 a | 0.491 b | 0.553 | 0.644 | 0.551 | 0.710 | 0.723 | 0.776 |

| (2) Social influence | 5.01 (1.28) | 0.763 | 0.241 c | 0.906 | 0.590 | 0.389 | 0.692 | 0.603 | 0.645 | 0.612 |

| (3) Convenience | 4.73 (1.15) | 0.579 | 0.306 | 0.348 | 0.803 | 0.500 | 0.645 | 0.647 | 0.657 | 0.639 |

| (4) Function | 3.66 (1.24) | 0.764 | 0.415 | 0.151 | 0.250 | 0.906 | 0.364 | 0.588 | 0.655 | 0.642 |

| (5) Emotion | 4.72 (1.23) | 0.742 | 0.304 | 0.479 | 0.416 | 0.132 | 0.895 | 0.624 | 0.662 | 0.678 |

| (6) Image | 4.45 (1.35) | 0.893 | 0.504 | 0.364 | 0.419 | 0.346 | 0.389 | 0.962 | 0.763 | 0.735 |

| (7) Desire | 4.15 (1.38) | 0.911 | 0.523 | 0.416 | 0.432 | 0.429 | 0.438 | 0.582 | 0.969 | 0.732 |

| (8) Behavioral intentions | 4.19 (1.22) | 0.826 | 0.602 | 0.375 | 0.408 | 0.412 | 0.460 | 0.540 | 0.536 | 0.934 |

| Standardized Estimate | t-Value | Hypothesis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Compatibility | → | Image | 0.373 | 6.854 * | Supported |

| H2 | Social influence | → | Image | 0.161 | 3.116 * | Supported |

| H3 | Convenience | → | Image | 0.163 | 3.130 * | Supported |

| H4 | Function | → | Image | 0.183 | 3.304 * | Supported |

| H5 | Emotion | → | Image | 0.150 | 2.599 * | Supported |

| H6 | Image | → | Desire | 0.885 | 23.877 * | Supported |

| H7 | Image | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.145 | 2.403 * | Supported |

| H8 | Desire | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.804 | 12.013 * | Supported |

| H9a | The moderating role of gender in the relationship between image and desire | Not supported | ||||

| H9b | The moderating role of gender in the relationship between image and behavioral intentions | Not supported | ||||

| H9c | The moderating role of gender in the relationship between desire and behavioral intentions | Supported | ||||

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 734.162, df = 234, χ2/df = 3.137, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.921, CFI = 0.944, TLI = 0.934, and RMSEA = 0.079 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, J.; Kim, H. The Effects of Expected Benefits on Image, Desire, and Behavioral Intentions in the Field of Drone Food Delivery Services after the Outbreak of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010117

Hwang J, Kim H. The Effects of Expected Benefits on Image, Desire, and Behavioral Intentions in the Field of Drone Food Delivery Services after the Outbreak of COVID-19. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Jinsoo, and Hyunjoon Kim. 2021. "The Effects of Expected Benefits on Image, Desire, and Behavioral Intentions in the Field of Drone Food Delivery Services after the Outbreak of COVID-19" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010117

APA StyleHwang, J., & Kim, H. (2021). The Effects of Expected Benefits on Image, Desire, and Behavioral Intentions in the Field of Drone Food Delivery Services after the Outbreak of COVID-19. Sustainability, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010117