Do Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Improve Financial Performance? A Perspective of the Islamic Banking Industry in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSRD and Financial Performance of Islamic Banks

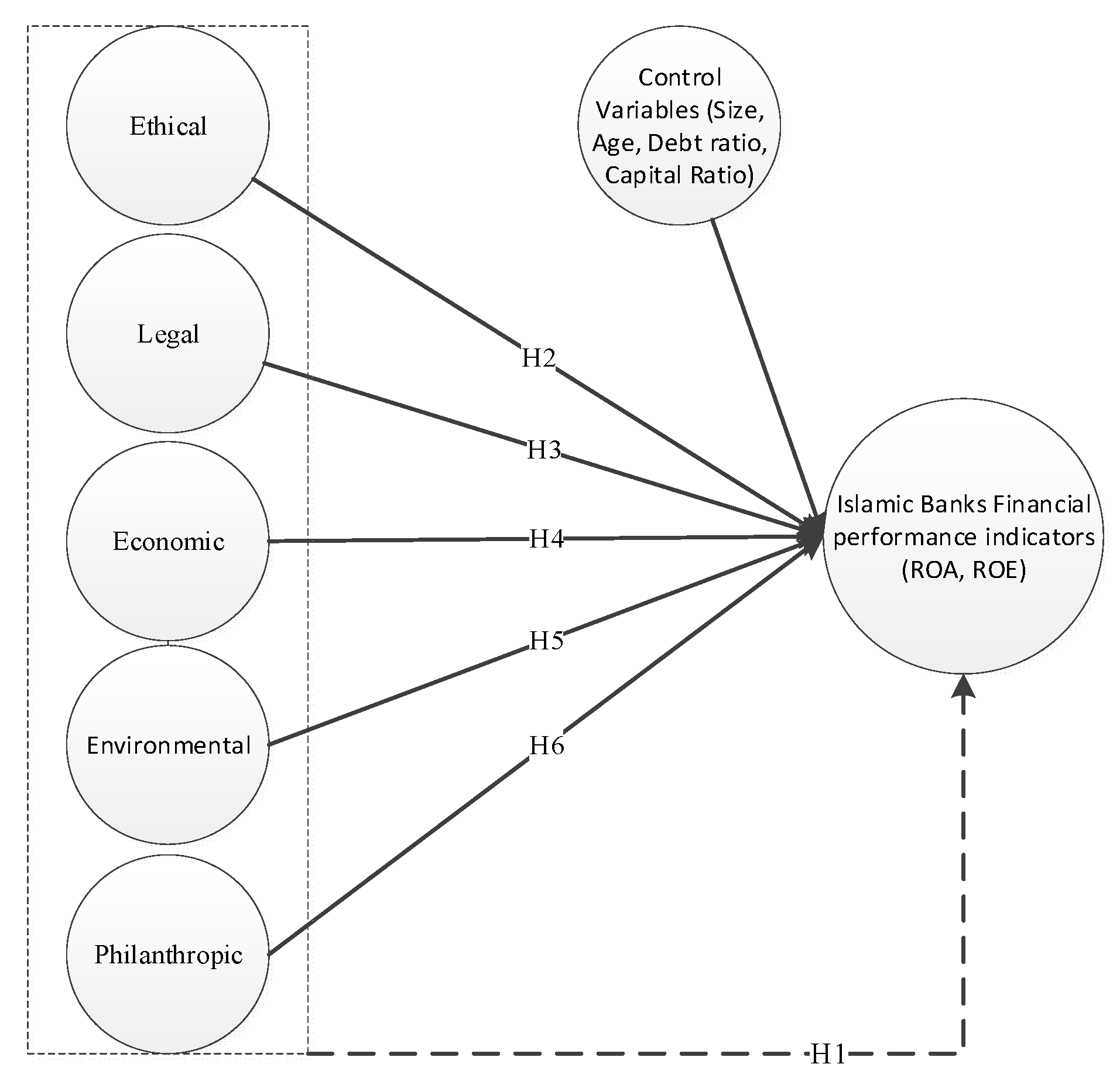

2.2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.3. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample for the Research

3.2. Measurement of Financial Performance

3.3. Measurement of CSR Disclosure

3.4. Estimation

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dimension of CSRD | Sub-Dimensions of CSRD |

|---|---|

| 1. Environment | ▪ Introduction to greenhouse products |

| ▪ Definition of greenhouse products | |

| ▪ Controlling measures for the emission of greenhouse gases (CO2, CO) | |

| ▪ Energy conservation | |

| ▪ Measures for water consumption/availability | |

| ▪ Biodiversity | |

| ▪ Transportation | |

| ▪ Supplier environmental assessment | |

| ▪ Conferences on environment-related issues | |

| ▪ Amount of donations to environmental protection | |

| ▪ Investments in sustainable developmental projects | |

| ▪ Investment in environmentally friendly projects | |

| ▪ Focus on risk-based corrective actions | |

| ▪ Measures for the restoration and protection of natural resources | |

| ▪ Stakeholders’ involvement in environmental issues | |

| ▪ Environmental grievances mechanism | |

| ▪ Climate change policy | |

| ▪ Any award for environmental achievement | |

| 2. Legal | ▪ Follow the Shariah and accounting rules |

| ▪ Whether the principles of Shariah are followed | |

| ▪ Whether the human rights labor laws are followed | |

| ▪ Whether the bank is dealing with legal products | |

| ▪ Whether the bank observes anti-money-laundering laws | |

| ▪ Provides secure transaction facility to customers | |

| ▪ Tax payment | |

| ▪ Any internal legal advisory committee | |

| ▪ Any legal Shariah committee | |

| ▪ Training on anti-corruption and other legal issues | |

| 3. Ethical | ▪ Any anti-money-laundering policy |

| ▪ Whether the transactions are free of Riba | |

| ▪ Whether the fund’s sources are disclosed for its customers | |

| ▪ Provides the correct information to its customers | |

| ▪ Prevents corruptions and irregularities in the banking system | |

| ▪ Any internal regulating body dealing with fraud and anti-corruption | |

| ▪ Any internal regulating body dealing with sexual harassment and workplace violence | |

| ▪ Policies regarding sexual harassment and workplace violence | |

| ▪ Non-discriminative policies regarding sex, age, and ethnicity | |

| ▪ Dealing with legal items only | |

| ▪ A proper code of ethics for the accountants | |

| ▪ A proper code of ethics for the internal auditors | |

| ▪ Disciplinary action committee | |

| ▪ Code of ethics for the employees | |

| ▪ Any grievances mechanism regarding ethical issues | |

| 4. Economic | ▪ Whether the revenues generated are disclosed |

| ▪ Employees’ wages and benefits are reported | |

| ▪ Whether the paid taxes are reported | |

| ▪ Whether profit and loss statements are reported | |

| ▪ Payments to the equity/capital owners reported | |

| ▪ Any community investment reported | |

| ▪ Economic value distributed in the form of operating cost reported | |

| ▪ Procurement policy | |

| ▪ Any economic Achievement Award | |

| ▪ Any economic award | |

| ▪ Economic grievances mechanism | |

| ▪ International economic appreciation award | |

| 5. Philanthropic/social | ❖ Community and Social Development |

| ▪ Donations for health issues | |

| ▪ Donations for sports activities | |

| ▪ Participating in relief and disaster management issues | |

| ▪ Donations for education | |

| ▪ Microfinance | |

| ▪ Funding other organizations for social activities | |

| ▪ Establishing a comprehensive link with the public industry/society | |

| ▪ Involvement in government-sponsored social activities | |

| ▪ Creating job opportunities | |

| ▪ Job opportunities for special persons | |

| ▪ Women branches | |

| ▪ Amount of zakat paid | |

| ▪ Those who receive the amount of zakat/zakat beneficiaries | |

| ▪ SSB attestation that the amount of zakat has been computed according to sharia | |

| ▪ SSB attestation that the sources and uses of zakat are according to | |

| ▪ Shariah | |

| ▪ Amount of Sadaqah paid | |

| ▪ Sadaqah beneficiaries | |

| ▪ Qard e Hassana paid | |

| ▪ Beneficiaries of Qard e Hassana | |

| ▪ Policy regarding debt | |

| ▪ Amount of debt written off | |

| ▪ Any public policy | |

| ▪ Credit committee | |

| ▪ Whether local communities are taken on board in social activities | |

| ❖ Product and Service Responsibilities | |

| ▪ Definition or glossary for a new product | |

| ▪ Introduction of SSB-approved new products | |

| ▪ Whether the new product is based on the concept of Shariah | |

| ▪ Any external or internal communication channel with stakeholders | |

| ▪ Regarding product | |

| ▪ Zero investment in non-permissible product or services | |

| ▪ Market survey and feasibility report | |

| ▪ Efforts for research and development promotion | |

| ▪ Products with customers’ health and safety | |

| ▪ Riba-free products | |

| ▪ Ensuring the customers’ privacy | |

| ▪ Whether customers are provided with access to the online banking services | |

| ❖ Commitment towards Employees | |

| ▪ Efforts for a diversified staff | |

| ▪ Employees’ health and safety | |

| ▪ Providing equal employment opportunities | |

| ▪ Provide training on Shariah awareness | |

| ▪ Provide training on professional skills and challenges | |

| ▪ Providing higher education opportunities to employees | |

| ▪ Employee appreciation | |

| ▪ Employees’ safety and protection | |

| ▪ Equal remuneration for men and women | |

| ▪ Proper promotion mechanism/promotion policy | |

| ▪ Remuneration committee | |

| ▪ Standard labor practices policy | |

| ▪ Employee management interaction | |

| ▪ Secure internet facilities for the employees | |

| ▪ Grievances mechanism for employees |

References

- Smith, A.; Adam, S. Theory of Moral Sentiments. In Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1759; pp. 1–244. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, L.; Rubbens, C.; Bonfiglioli, E. Research: Big business, big responsibilities. Corp. Gov. 2003, 3, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce II, J.A.; Doh, J.P. The high impact of collaborative social initiatives. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2005, 46, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dusuki, A.W. What Does Islam Say about Corporate Social Responsibility? Rev. Islam. Econ. 2008, 12, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.M.; Usman, M. Corporate Social Responsibility in Islamic Banks in Pakistan. J. Islam. Bus. Manag. 2016, 6, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Norafifah, A.; Sudin, H. Perceptions of Malaysian corporate customers towards Islamic banking products and services. Int. J. Islam. Financ. Serv. 2002, 3, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. Investing in CSR to Enhance Customer Value. In Director Notes No. 3; The Conference Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, February 2011; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Quazi, A.; Amran, A.; Nejati, M. Conceptualizing and measuring consumer social responsibility: A neglected aspect of consumer research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Marimuthu, M.; Pisol, M. The nexus of sustainability practices and financial performance: From the perspective of Islamic banking. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhi, S.; Makki, M. Determinants of Corporate Philanthropy in Pakistan. Pakistan J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2008, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Agus, M.; Indrarini, H.; Lee, L.R.; Martinov-Bennie, N.; Soh, D.S.B.; Al, A.; Ahmed, A.; Hossain, M.A.M.S.; Alkhatib, K.; Marji, Q.; et al. Enforcement Rules of the University Act. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, S.; Hassan, M.K.; Mohd Yusof, R.; Naiimi, N. Islamic Banking Sustainability: A Review of Literature and Directions for Future Research. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 440–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational Legitimacy: Social Values and Organizational Behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Fauzi, H.; Purwanto, Y.; Darus, F.; Yusoff, H.; Zain, M.M.; Malianna, D.; Naim, A.; Nejati, M. Social Responsibility Disclosure in Islamic Banks: A Comparative Study of Indonesia and Malaysia. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2017, 15, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Zainuddin, Y.H.; Haron, H. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Othman, S.; Othman, R. Islamic Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Reputation and Performance. Proc. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2012, 6, 1070. [Google Scholar]

- Farag, H.; Mallin, C.; Ow-Yong, K. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in Islamic banks. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 103, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Haniffa, R.; Hudaib, M. Exploring the ethical identity of Islamic Banks via communication in annual reports. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, A.; Md Hashim, M.F.A.; Abu Bakar, F. Corporate Social Reporting: A Preliminary Study of Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad ( BIMB ). Issues Soc. Environ. Account. 2010, 4, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belal, A.R.; Abdelsalam, O.; Nizamee, S.S. Ethical Reporting in Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited (1983–2010). J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ararat, M. A development perspective for “corporate social responsibility”: Case of Turkey. Corp. Gov. 2008, 8, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Theory and Practice in a Developing Country Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Bansal, P. Instrumental and Integrative Logics in Business Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, T.; Walters, G. Financial Sustainability Within UK Charities: Community Sport Trusts and Corporate Social Responsibility Partnerships. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2012, 24, 606–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D.J.; Lloret, A. Sustainability and competitiveness in Mexico. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 1252–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SBP. Islamic Banking Bulletin December 2017 Islamic Banking Department State Bank of Pakistan; 2017; Available online: http://www.sbp.org.pk/ibd/bulletin/2017/Dec.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Griffin, J.J.; Mahon, J.F. The Corporate Social Performance and Corporate Financial Performance Debate: Twenty-Five Years of Incomparable Research. Bus. Soc. 1997, 36, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rehman, H.U.; Ali, W.; Khan, M.; Alharthi, M.; Qureshi, M.I.; Jan, A. Boardroom gender diversity: Implications for corporate sustainability disclosures in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 244, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delai, I.; Takahashi, S. Corporate sustainability in emerging markets: Insights from the practices reported by the Brazilian retailers. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Rahman, H.U.; Muneer, S.; Butt, B.Z.; Isah-Chikaji, A.; Memon, M.A. Nexus between government initiatives, integrated strategies, internal factors and corporate sustainability practices in Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Musibah, A.S.; Alfattani, W.S.B.W.Y. The Mediating Effect of Financial Performance on the Relationship between Shariah Supervisory Board Effectiveness, Intellectual Capital and Corporate Social Responsibility, of Islamic Banks in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Zulkifli, N.; Muhamad, R. Looking for evidence of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance in an emerging market. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2011, 3, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, S.; Hull, C.E.; Tang, Z. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Corporate Social Performance Strengths and Concerns. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970; 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Salzmann, A. Is there a moral economy of state formation? Religious minorities and repertoires of regime integration in the Middle East and Western Europe, 600-1614. Theory Soc. 2010, 39, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, S.M.; Ali, M. Stanford Social Innovation Review; 2018; Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/philanthropy_in_pakistan# (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Kiarie, M. Corporate citizenship: The changing legal perspective in Kenya. In Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary CSR Research Conference, Nottingham, UK, 22–23 October 2004; International Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility (ICCSR): Nottingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.H.; Metcalf, R.W. The Relationship between Pollution Control Record and Financial Indicators Revisited. Account. Rev. 1980, 55, 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Jaggi, B.; Freedman, M. An examination of the impact of pollution performance on economic and market performance: Pulp and paper firms. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 1992, 19, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, L.; Roberts, R.W. Corporate social performance, financial performance and institutional ownership in Canadian firms. Account. Forum 2007, 31, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taman, S. The concept of corporate social responsibility in Islamic law. Indiana Int. Comp. Law Rev. 2011, 21, 481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, A.A. Data in Search of a Theory: A Critical Examination of the Relationships Among Social Performance, Social Disclosure, and Economic Performance of U.S. Firms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 540–557. [Google Scholar]

- Pava, M.L.; Krausz, J. The association between corporate social-responsibility and financial performance: The paradox of social cost. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Questioning the domain of the business ethics curriculum. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, E.; Asutay, M.; Dixon, R.; Mohammad, S. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Financial Performance: Evidence from the GCC Islamic Banking Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N.; Katz, J.N. Time-series–cross-section data: What have we learned in the past few years? Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2001, 4, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, N.; Katz, J.N. What to do (and not to do) with time- series cross-section data. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1995, 89, 634–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoechle, D. Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. Stata J. 2007, 7, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Ibrahim, M.Y.; Che-Ahmad, A. Physical characteristics of the chief executive officer and firm accounting and market based performance. Asian J. Account. Gov. 2017, 8, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H.U.; Rehman, S.; Zahid, M. The impact of boardroom national diversity on firms’ performance and boards’ monitoring in emerging markets: A case of Malaysia. City Univ. Res. Journa 2018, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |

| ROA | −0.14 | 0.95 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 1.21 | 0.47 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| ROE | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.91 |

| Firm Size | 0.10 | 11.81 | 8.46 | 4.93 | −1.22 | 0.47 | −0.54 | 0.91 |

| Capital ratio | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.83 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| Debt ratio | 2.78 | 20.5 | 11.59 | 5.61 | −0.32 | 0.47 | −1.08 | 0.91 |

| Age | 2 | 14 | 8.25 | 3.08 | −0.17 | 0.47 | −0.42 | 0.91 |

| CSRD | 35 | 78 | 57.38 | 14.26 | −0.19 | 0.47 | −1.36 | 0.91 |

| Environmental | 2 | 10 | 5.21 | 2.58 | 0.25 | 0.47 | −1.04 | 0.91 |

| Legal | 3 | 9 | 6.71 | 1.45 | −0.26 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.91 |

| Ethical | 2 | 13 | 7.88 | 3.71 | −0.37 | 0.47 | −1.33 | 0.91 |

| Economic | 5 | 10 | 7.04 | 1.68 | 0.40 | 0.47 | −0.81 | 0.91 |

| Philanthropic/social | 18 | 37 | 26.46 | 6.15 | 0.24 | 0.47 | −1.14 | 0.91 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA (1) | 1 | |||||||||||

| Size (2) | −0.03 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age (3) | −0.01 | 0.90 * | 1 | |||||||||

| Capital Ratio (4) | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 1 | ||||||||

| Debt Ratio (5) | −0.06 | 0.72 ** | 0.88 ** | 0.11 | 1 | |||||||

| Environment (6) | 0.02 | 0.80 * | 0.79 ** | −0.09 | 0.87 * | 1 | ||||||

| Legal (7) | −0.647 ** | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 1 | |||||

| Ethical (8) | −0.70 * | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.81 ** | 1 | ||||

| Economic (9) | 0.55 ** | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.78 ** | 0.73 ** | 1 | |||

| Philanthropic (10) | 0.73 ** | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.77 ** | 0.88 ** | 0.78 ** | 1 | ||

| CSRD (11) | 0.56 ** | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.80 ** | 0.81 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.68 ** | 1 | |

| Lag ROA (12) | 0.41 | 0.89 ** | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.11 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.63 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.78 ** | 1 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA OLS | ROA GLS Random | ROA GLS Fixed | ROE OLS | ROE GLS Random | ROE GLS Fixed | |

| CSRD | −0.587 ** | −0.587 *** | −0.053 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.009 |

| (0.201) | (0.201) | (0.286) | (0.146) | (0.146) | (0.109) | |

| Firm size | −1.331 | −1.331 | 0.396 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 1.094 * |

| (1.344) | (1.344) | (1.341) | (0.740) | (0.740) | (0.524) | |

| Capital ratio | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.725 | −0.050 | −0.050 | 0.410 ** |

| (0.254) | (0.254) | (0.481) | (0.136) | (0.136) | (0.179) | |

| Debt ratio | −0.502 | −0.502 | −0.331 | −0.365 | −0.365 | −0.322 |

| (0.492) | (0.492) | (0.514) | (0.265) | (0.265) | (0.193) | |

| Age | 2.303 | 2.303 * | 0.876 | −0.279 | −0.279 | −1.630 |

| (1.332) | (1.332) | (3.792) | (0.730) | (0.730) | (1.438) | |

| Lag ROA | 0.130 | 0.130 | −0.067 | - | - | - |

| (0.250) | (0.250) | (0.261) | - | - | - | |

| Years | −0.356 * | −0.356 * | −0.215 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.344 |

| (0.184) | (0.184) | (1.090) | (0.099) | (0.099) | (0.400) | |

| Lag ROE | - | - | - | 0.787 *** | 0.787 *** | 0.164 |

| - | - | - | (0.144) | (0.144) | (0.199) | |

| _cons | 716.232 * | 716.232 * | 433.129 | −31.300 | −31.300 | −693.116 |

| (370.697) | (370.697) | (2195.810) | (199.219) | (199.219) | (806.422) | |

| Obs. | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| R−squared | 0.542 | 0.542 | 0.344 | 0.837 | 0.837 | 0.521 |

| Hausman Test (Chi2) | - | 8.3 | - | - | - | 34.82 *** |

| Prob. > Chi 2 | - | 0.307 | - | - | - | 0.000 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA (OLS) | ROA (GLS Random) | ROA (GLS Fixed) | ROE (OLS) | ROE (GLS Random) | ROE (GLS Fixed) | |

| Environmental | 0.821 ** | 0.821 ** | 0.723 | 0.283 | 0.283 | 0.142 |

| (0.324) | (0.324) | (0.411) | (0.204) | (0.204) | (0.200) | |

| Legal | −0.011 | −0.011 | 0.364 | −0.102 | −0.102 | 0.364 |

| (0.304) | (0.304) | (0.394) | (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.205) | |

| Ethical | −0.436 | −0.436 | −1.052 * | 0.472* | 0.472 ** | −0.347 |

| (0.370) | (0.370) | (0.548) | (0.232) | (0.232) | (0.320) | |

| Economic | 0.645 * | 0.645 * | 0.384 | 0.583 ** | 0.583 *** | 0.062 |

| (0.339) | (0.339) | (0.376) | (0.203) | (0.203) | (0.222) | |

| Philanthropic | −0.598 | −0.598 | −0.675 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.056 |

| (0.399) | (0.399) | (0.583) | (0.230) | (0.230) | (0.289) | |

| Firm size | −0.799 | −0.799 | −0.287 | 0.556 | 0.556 | 1.244 * |

| (1.067) | (1.067) | (1.181) | (0.631) | (0.631) | (0.575) | |

| Capital ratio | 0.086 | 0.086 | 0.926 | −0.238 | −0.238 | 0.698 * |

| (0.195) | (0.195) | (0.686) | (0.157) | (0.157) | (0.356) | |

| Debt ratio | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.325 | −0.326 | −0.326 | −0.285 |

| (0.371) | (0.371) | (0.487) | (0.218) | (0.218) | (0.237) | |

| Firm age | 1.821 | 1.821 * | 3.936 | 0.119 | 0.119 | −1.432 |

| 0.821 ** | 0.821 ** | 0.723 | 0.283 | 0.283 | 0.142 | |

| Lag ROA | 0.087 | 0.087 | 0.042 | - | - | - |

| (0.216) | (0.216) | (0.217) | - | - | - | |

| Years | −0.509 ** | −0.509 *** | −0.973 | −0.269 * | −0.269 * | 0.328 |

| (0.186) | (0.186) | (1.169) | (0.139) | (0.139) | (0.571) | |

| Lag ROE | - | - | - | 0.722 *** | 0.722 *** | 0.018 |

| - | - | - | (0.203) | (0.203) | (0.278) | |

| _cons | 1026.163 ** | 1026.163 *** | 1959.252 | 542.467 * | 542.467 * | −660.113 |

| (374.915) | (374.915) | (2355.501) | (279.282) | (279.282) | (1151.203) | |

| Obs. | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 23 |

| R-squared (Overall) | 0.830 | 0.830 | 0.752 | 0.928 | 0.928 | 0.715 |

| Hausman Test (Chi2) | - | 5.000 | - | - | 11.25 | - |

| Prob. > Chi 2 | - | 0.931 | - | - | 0.423 | - |

| (PCSEs) | (PCSEs) | (PCSEs) | (PCSEs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | ROE | ROA | ROE | |

| CSRD | −0.587 *** | 0.022 | - | - |

| (0.198) | (0.072) | - | - | |

| Firm size | −1.331 | 0.667 | −0.799 | 0.556 |

| (1.017) | (0.545) | (0.869) | (0.523) | |

| Capital ratio | 0.028 | −0.050 | 0.086 | −0.238 ** |

| (0.239) | (0.104) | (0.202) | (0.119) | |

| Debt ratio | −0.502 | −0.365 *** | 0.005 | −0.326 ** |

| (0.481) | (0.132) | (0.243) | (0.159) | |

| Firm age | 2.303 ** | −0.279 | 1.821 ** | 0.119 |

| (0.921) | (0.494) | (0.790) | (0.492) | |

| Lag of ROA | 0.130 | - | 0.087 | - |

| (0.241) | - | (0.198) | - | |

| Lag of ROE | - | 0.787 *** | - | 0.722 *** |

| - | (0.102) | - | (0.165) | |

| Environmental | - | - | 0.821 *** | 0.283 |

| - | - | (0.262) | (0.179) | |

| Legal | - | - | −0.011 | −0.102 |

| - | - | (0.189) | (0.131) | |

| Ethical | - | - | 0.436 | 0.472 *** |

| - | - | (0.339) | (0.156) | |

| Economic | - | - | 0.645 ** | 0.583 *** |

| - | - | (0.306) | (0.181) | |

| Philanthropic | - | - | −0.598 | 0.009 |

| - | - | (0.382) | (0.111) | |

| Years | −0.356 *** | 0.015 | −0.509 *** | −0.269 ** |

| (0.115) | (0.062) | (0.140) | (0.106) | |

| Constant | 716.232 *** | −31.300 | 1026.163 *** | 542.467 ** |

| (232.074) | (124.751) | (281.519) | (213.381) | |

| Obs. | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| R-squared | 0.542 | 0.837 | 0.830 | 0.928 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ur Rehman, Z.; Zahid, M.; Rahman, H.U.; Asif, M.; Alharthi, M.; Irfan, M.; Glowacz, A. Do Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Improve Financial Performance? A Perspective of the Islamic Banking Industry in Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083302

Ur Rehman Z, Zahid M, Rahman HU, Asif M, Alharthi M, Irfan M, Glowacz A. Do Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Improve Financial Performance? A Perspective of the Islamic Banking Industry in Pakistan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083302

Chicago/Turabian StyleUr Rehman, Zia, Muhammad Zahid, Haseeb Ur Rahman, Muhammad Asif, Majed Alharthi, Muhammad Irfan, and Adam Glowacz. 2020. "Do Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Improve Financial Performance? A Perspective of the Islamic Banking Industry in Pakistan" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083302

APA StyleUr Rehman, Z., Zahid, M., Rahman, H. U., Asif, M., Alharthi, M., Irfan, M., & Glowacz, A. (2020). Do Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures Improve Financial Performance? A Perspective of the Islamic Banking Industry in Pakistan. Sustainability, 12(8), 3302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083302