Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Agriculture Sector: The Nexus of the Triple Bottom Line Measurement Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Reviews

2.1. Sustainability Concerns and Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Agriculture

2.2. Theory of Planned Behavior and Hypotheses Development

2.3. Triple Bottom Line and sustainable Agriculture Entrepreneurship

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Structural Model Analysis

3.3. Measurement Items

4. Results

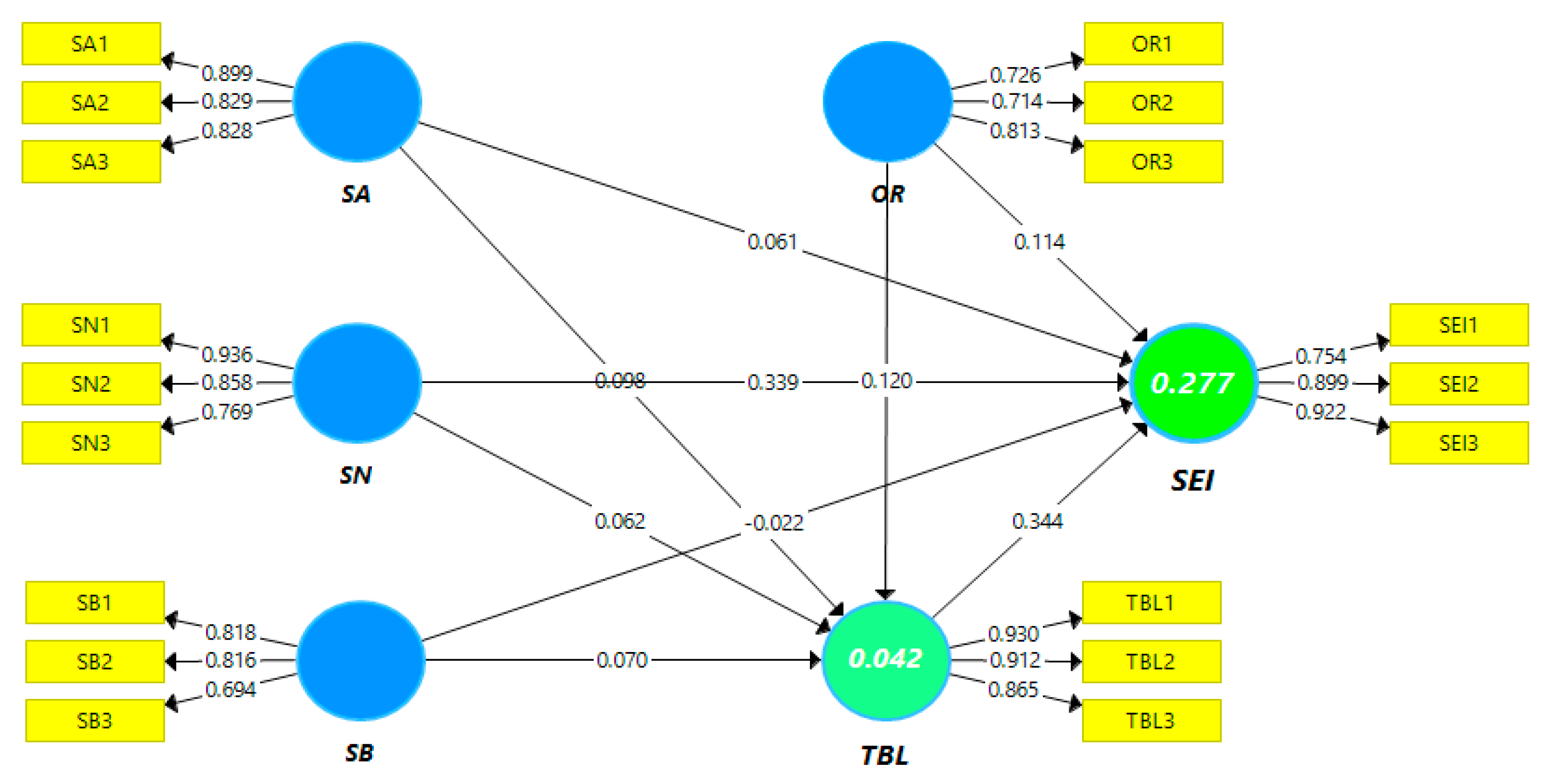

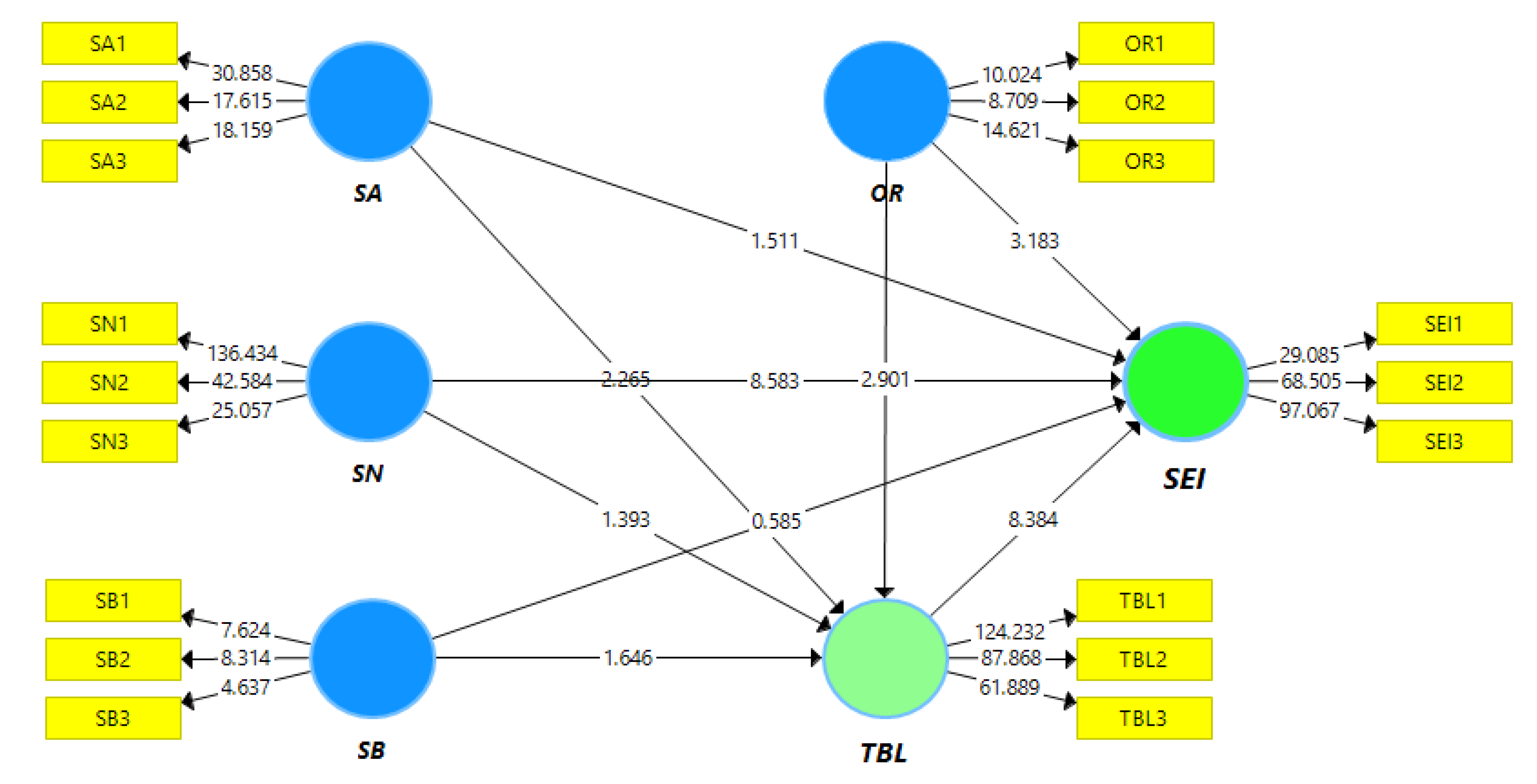

4.1. Assessment of Structural Model

4.2. Assessment of Measurement Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implementation

5.2. Academic Implementation and Policy Implications

5.3. Recommendation and Limitations

5.4. Future Researches

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mupfasoni, B.; Kessler, A.; Lans, T. Sustainable agricultural entrepreneurship in Burundi: Drivers and outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2018, 25, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, T.; Seuneke, P.; Wageningen, A.H.; Klerkx, L. Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Technology and Innovation Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. The triple bottom line: Does it all add up?: Assessing the sustainability of business and CSR. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2013; pp. 1–186. ISBN 9781849773348. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Krueger, N.F. An Intentions-Based Model of Entrepreneurial Teams’ Social Cognition. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2002, 27, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Stellingwerf, J.J. Sustainable entrepreneurship: The motivations and challenges of sustainable entrepreneurs in the renewable energy industry. Amana-Key 2012, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, H.; Shepherd, D.A. Recognizing opportunities for sustainable development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Rowlands, I.H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Choice Rev. Online 1999, 36, 36–3997. [Google Scholar]

- Koe, W.-L. The relationship between Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation (IEO) and entrepreneurial intention. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargani, G.R.; Zhou, D.; Mangan, T.; Rajper, H. Determinants of Personality Traits Influence on Entrepreneurial Intentions Among Agricultural Students Evidence from Two Different Economies. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory of Aggression. J. Commun. 1978, 28, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaijun, Y.; Ichwatus Sholihah, P. A comparative study of the Indonesia and Chinese educative systems concerning the dominant incentives to entrepreneurial spirit (desire for a new venturing) of business school students. J. Innov. Entrep. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuringsih, K.; Nuryasman, M.N.; IwanPrasodjo, R.A. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention: The Perceived of Triple Bottom Line among Female Students. J. Manaj. 2019, 23, 168–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hollos, D.; Blome, C.; Foerstl, K. Does sustainable supplier co-operation affect performance? Examining implications for the triple bottom line. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenassato, D.; Trierweiller, A.C.; Bornia, A.C.; De Azevedo, B.M.; Erdmann, R.H.; Campos, L.M.S.S. Development of a sustainable behavior measurement scale of undergraduate students. Espacios 2015, 36, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; Sexton, D.L.; Landstrom, H. Handbook of Entrepreneurship; Blackwell Publishers Ltd: Cheltenham, UK, 2001; Volume 46, ISBN 9781849808231. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, T.; Bayley, A. Sustainable Development-Linking Economy, Society, Environment; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, I.A.; Latif, A.; Koe, W.L. SMEs’ Intention towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 4, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddi, H. Triple Bottom Line and Sustainability: A Literature Review. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2015, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, N.; Wolfgramm, R.; Shepherd, D. Ecopreneurs as change agents; opportunities, innovations and motivations. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, R.D.; Quinn, M.J. Psychopathy and autonomic conditioning. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1971, 77, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Burke, T. The Green Capitalism: How Industry Can Make Money-and Protect the Environment; Victor Gollancz: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schaper, M. The essence of ecopreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 38, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abina, M.; Oyeniran, I.; Onikosi-Alliyu, S. Determinants of eco entrepreneurial intention among students: A case study of University students in Ilorin and Malete. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2015, 8, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotchen, M.J. Some microeconomics of eco-entrepreneurship. In Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 25–37. ISBN 1048-4736. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.W.; Walley, E.E. The green entrepreneur: Opportunist, Maverick or Visionary? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2004, 1, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.K.; Belz, F.M. Sustainable entrepreneurship: What it is. Handb. Entrep. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2015, 1, 30–71. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin, A.; Spangenberg, J.H. A guide to community sustainability indicators. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2000, 20, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Winn, M.I. Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlange, L.E. Stakeholder Perception in Sustainable Entrepreneurship: The Role of Managerial and Organizational Cognition. In Proceedings of the Corporate Responsibility Research Conference, First Word Simposium on Sustainable Entrepreneurship, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK, 15–17 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weidinger, C.; Fischler, F.; Schmidpeter, R. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Business Success Through Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Koe, W.L.; Omar, R.; Majid, I.A. Factors Associated with Propensity for Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Greening Tomorrow’s Markets: An Advantage or a Way to Hijack the Sustainability Agenda. In Proceedings of the Curtin International Business Conference-Category-Business Sustainability (paper# 4), Sarawak, Malaysia, 10–12 December 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, T. Ecopreneurship as a Solution to Environmental Problems: Implications for College Level Entrepreneurship Education. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 264–288. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F. The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, F.; Young, W. Sustainability Entrepreneurs. Greener Manag. Int. 2009, 2006, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.Y.; Gray, E.R. The venture development processes of “sustainable” entrepreneurs. Manag. Res. News 2008, 31, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuringsih, K.; Puspitowati, I. Determinants of eco entrepreneurial intention among students: Study in the entrepreneurial education practices. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 7281–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.L.; Majid, I.A. Socio-Cultural Factors and Intention towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Eurasian J. Bus. Econ. 2014, 7, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, B. Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intention. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icek, A.; Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Handb. Theor. Soc. Psychol. Vol. 1 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Wong, P.K. An exploratory study of technopreneurial intentions: A career anchor perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remeikiene, R.; Startiene, G.; Dumciuviene, D. Explaining Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students: The Role of Entrepreneurial Education. In Proceedings of the Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference, Zadar, Croatia, 19–21 June 2013; pp. 299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Maresch, D.; Harms, R.; Kailer, N.; Wimmer-Wurm, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial intention of students in science and engineering versus business studies university programs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.J.; Usdan, S.; Nelson, S.; Umstattd, M.R.; LaPlante, D.; Perko, M.; Shaffer, H. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict gambling behavior. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010, 24, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Testing the Entrepreneurial Intention Model on a two-country Sample. Doc. Treb. 2006, 6/7, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolvereid, L. Organizational Employment versus Self-Employment: Reasons for Career Choice Intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 20, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-referent mechanisms in social learning theory. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F. Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2008, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D.; Selcuk, S.S. Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students? J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2009, 33, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Khalid, S.A.; Othman, M.; Jusoff, H.K.; Rahman, N.A.; Kassim, K.M.; Zain, R.S. Entrepreneurial Intention among Malaysian Undergraduates. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelard, P.; Saleh, K.E. Impact of some contextual factors on entrepreneurial intention of university students. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 10707–10717. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti, R.D.; Martdianty, F. Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions by Using Theory of Planned Behavior: The Case in Indonesia. South East Asian J. Manag. 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denanyoh, R.; Adjei, K.; Nyemekye, G.E. Factors That Impact on Entrepreneurial Intention of Tertiary Students in Ghana. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Res. 2015, 5, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sahinidis, A.; Giovanis, A.; Sdrolias, L. The Role of Gender on Entrepreneurial Intention Among Students: An Empirical Test of the Theory of Planned Behavior in a Greek University. Int. J. Integr. Inf. Manag. 2014, 1, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, P.; Caetano, A.; Santos, S.C. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy in Italy: An empirical study from a gender perspective. TPM—Testing Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 22, 485–506. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M.; Ben Boubaker Gherib, J.; Biwolé, V.O. Sustainable Entrepreneurship: Is Entrepreneurial will Enough? A North-South Comparison; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 99, ISBN 0021698443566. [Google Scholar]

- Levenburg, N.M.; Schwarz, T.V. Entrepreneurial Orientation among the Youth of India. J. Entrep. 2008, 17, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.; Ferreira, J.; Raposo, M.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Dinis, A. Entrepreneurial intention among secondary students: Findings from Portugal. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2011, 13, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Liñán, F.; Moriano, J.A. Beyond entrepreneurial intentions: Values and motivations in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.F.; Pradenas, L.; Parada, V. A cross-cultural assessment of three theories of pro-environmental behavior: A comparison between business students of chile and the united states. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended Theory of Planned Behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Nauta, M.M.; Saucier, A.M.; Woodard, L.E. Interpersonal influences on students’ academic and career decisions: The impact of sexual orientation. Career Dev. Q. 2001, 49, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. Effects of role models and gender on students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 694–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Auken, H.; Fry, F.L.; Stephens, P. the Influence of Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Dev. Entrep. 2006, 11, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.M.; Meek, W.R. Gender and entrepreneurship: A review and process model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 428–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L.; Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L.; Krueger, N.F.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Sustainable behavior and quality of life. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 241–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterman, N.E.; Kennedy, J. Enterprise education: Perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I.A.; Koe, W.L. Sustainable Entrepreneurship (SE): A Revised Model Based on Triple Bottom Line (TBL). Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mark-Herbert, C.; Rotter, J.; Pakseresht, A. A triple bottom line to ensure Corporate Responsibility. In Timeless Cityland: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Building the Sustainable Human Habitat; Public Eye: Zürich, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hockerts, K.; Wustenhagen, R.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.E.A.; Clifford, A. Ecopreneurship—A new approach to managing the triple bottom line. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2007, 20, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, B.D. Sustainability-driven entrepreneurship: Principles of organization design. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.; Haynes, M. Entrepreneurship Education in America’s Major Universities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1991, 15, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P. The Distinctive Importance of Sustainable Entrepreneurship. Curr. Opin. Creat. Innov. Entrep. 2013, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ayob, N.; Yap, C.S.; Amat Sapuan, D.; Abdul Rashid, M.Z. Social entrepreneurial intention among business undergraduates: An emerging economy perspective. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2013, 15, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P. Sustainable venture capital—Catalyst for sustainable start-up success? J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.; Pivo, G. The Triple Bottom Line and Sustainable Economic Development Theory and Practice. Econ. Dev. Q. 2017, 31, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.; Kiefer, K.; York, J.G. Distinctions not Dichotomies: Exploring Social, Sustainable, and Environmental Entrepreneurship. Adv. Entrep. Firm Emerg. Growth 2011, 13, 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, H.; Karlsson, N.P.E.E.; Lindgren, J.; Andersson, S.; Svensson, G. Re-testing and validating a triple bottom line dominant logic for business sustainability. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Curtis, A.; Davidson, P. Can the ‘triple bottom line’ concept help organisations respond to sustainability issues? In Proceedings of the Conference proceedings in 5th Australian Stream Management Conference, Albury, New South Wales, Australia, 21–25 May 2007; pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.B. Sustainability as a Norm. Techné Res. Philos. Technol. 1997, 2, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 38, ISBN 1483377466. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Benitez-Amado, J. How information technology influences environmental performance: Empirical evidence from China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesen, H. Personality or environment? A comprehensive study on the entrepreneurial intentions of university students. Educ. + Train. 2013, 55, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Chen, Y. Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Shrivatava, A. Do young managers in a developing country have stronger entrepreneurial intentions? Theory and debate. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 1197–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Stuetzer, M. Integrating psychological approaches to entrepreneurship: The Entrepreneurial Personality System (EPS). Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; van Gelderen, M.; Fink, M. Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.B.L.; Johnson, D. Establishing individual differences related to opportunity alertness and innovation dependent on academic-career training. J. Manag. Dev. 2006, 25, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.; Babin, B. Exploring Marketing Research William; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 1305831241. [Google Scholar]

- Höck, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hock, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Höck, M.; Ringle, C.M. Local strategic networks in the software industry: An empirical analysis of the value continuum. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2010, 4, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Nternational J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. Handb. Res. Int. Advert. 2012, 252, 252–276. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 1483377385. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, F.A. The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust towards green purchase intention of inverter air conditioner in Surabaya. IBuss Manag. 2015, 3, 252–260. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Hills, G.E.; Seibert, S.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G.; Liñán, F. Considering business start-up in recession time: The role of risk perception and economic context in shaping the entrepreneurial intent. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2013, 19, 633–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.; Langan-Fox, J.; Grant, S. Entrepreneurship Research and Practice: A Call to Action for Psychology. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sources | Topic | Respondents | Results | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | Socio-cultural factors and intention towards sustainable entrepreneurship | 404 Small and Mid-size Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia | Factors are significant to an inclination for sustainable entrepreneurship | 2014 |

| [24] | Factors associated with propensity for sustainable entrepreneurship | 256 SMEs in Malaysia | The four determinants are essential for sustainable entrepreneurial tendencies. | 2014 |

| [28] | The impact of environment concern, entrepreneurial education, self-efficacy, the perceived barrier to entry, perceived support, and experience toward eco-entrepreneurial intentions | 250 students at the university in Ilorin and Malete, Nigeria | Environmental fear perceived barriers to entry and perceived support has a significant impact on ecological entrepreneurial intentions | 2015 |

| [9] | The effect of sustainability attitude, social norms, perceived desirability, and perceived feasibility toward propensity for sustainable entrepreneurship | 404 Small and Mid-size Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia | The four determining factors are the substantive trends in sustainable entrepreneurship | 2016 |

| [20] | The mediation effect among sustainable value, sustainable attitude, social norms, and government legislation to the intention toward sustainable entrepreneurship | 404 SMEs in Malaysia | Sustainable values, sustainable beliefs, subjective norms, and administrative regulations are essential for intentions | 2017 |

| [15] | The impact of educational support, structural support, formal networking, informal networking, green value, prior experience, and role models to eco-entrepreneurial intention. | 400 students at an entrepreneurial university in Jakarta | Structural terms, formal and informal networks, green values, and experience have essential implications for eco-entrepreneurship intentions | 2019 |

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho-A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 0.619 | 0.634 | 0.796 | 0.566 |

| SA | 0.816 | 0.851 | 0.889 | 0.727 |

| SB | 0.685 | 0.716 | 0.821 | 0.605 |

| SEI | 0.823 | 0.84 | 0.896 | 0.742 |

| SN | 0.82 | 0.902 | 0.892 | 0.735 |

| TBL | 0.887 | 0.909 | 0.929 | 0.815 |

| Variables | OR | SA | SB | SEI | SN | TBL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 0.752 | |||||

| SA | 0.11 | 0.853 | ||||

| SB | 0.103 | 0.386 | 0.778 | |||

| SEI | 0.148 | 0.129 | 0.052 | 0.861 | ||

| SN | –0.049 | 0.047 | –0.006 | 0.357 | 0.857 | |

| TBL | 0.135 | 0.141 | 0.119 | 0.624 | 0.061 | 0.903 |

| Paths | β Values | (M) | (SD) | T Stat(s) | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR -> SEI | 0.114 | 0.116 | 0.037 | 3.121 | 0.002 | Supported |

| OR -> TBL | 0.12 | 0.124 | 0.042 | 2.833 | 0.005 | Supported |

| SA -> SEI | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.04 | 1.515 | 0.13 | Not Supported |

| SA -> TBL | 0.098 | 0.099 | 0.045 | 2.193 | 0.028 | Supported |

| SB -> SEI | –0.022 | –0.02 | 0.038 | 0.586 | 0.558 | Not Supported |

| SB -> TBL | 0.07 | 0.077 | 0.043 | 1.611 | 0.107 | Not Supported |

| SN -> SEI | 0.339 | 0.34 | 0.041 | 8.281 | 0.000 | Supported |

| SN -> TBL | 0.063 | 0.065 | 0.045 | 1.385 | 0.166 | Not Supported |

| TBL -> SEI | 0.344 | 0.343 | 0.043 | 8.081 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Paths | β Values | (M) | (SD) | T Stat(s) | p-Values | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR -> TBL -> SEI | 0.041 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 2.599 | 0.009 | Significant |

| SA -> TBL -> SEI | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 2.078 | 0.038 | Significant |

| SB -> TBL -> SEI | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 1.598 | 0.11 | No Effect |

| SN -> TBL -> SEI | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.016 | 1.329 | 0.184 | No Effect |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sargani, G.R.; Zhou, D.; Raza, M.H.; Wei, Y. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Agriculture Sector: The Nexus of the Triple Bottom Line Measurement Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083275

Sargani GR, Zhou D, Raza MH, Wei Y. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Agriculture Sector: The Nexus of the Triple Bottom Line Measurement Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083275

Chicago/Turabian StyleSargani, Ghulam Raza, Deyi Zhou, Muhammad Haseeb Raza, and Yuzhi Wei. 2020. "Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Agriculture Sector: The Nexus of the Triple Bottom Line Measurement Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083275

APA StyleSargani, G. R., Zhou, D., Raza, M. H., & Wei, Y. (2020). Sustainable Entrepreneurship in the Agriculture Sector: The Nexus of the Triple Bottom Line Measurement Approach. Sustainability, 12(8), 3275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083275