Abstract

Cause-related marketing (CRM) has been a crucial concept of sport marketing literature in the professional sport context. However, there is little evidence available to address the effectiveness of CRM when the levels of sport fans’ embedded psychological characteristics helping others are considered. The present study aimed to investigate the influence of sport fans’ perceived CRM motive of a sport team on fan attitude and purchase intention for the team-licensed products, and the moderating effects of sport fans’ altruism on the relationships among these variables in the context of the Korean professional baseball league. A total of 164 Korean baseball fans participated in the present study. Results revealed that sport fans’ perceived CRM motive significantly affected fan attitude and purchase intention for the team-licensed products, and fan attitude also had a significant impact on purchase intention. Moreover, sport fans’ altruism had significant moderating effects on the relationships between perceived CRM motive and purchase intention, as well as team attitude and purchase intention for the team-licensed products. Consequently, the present study might demonstrate that professional sport fans with high altruism are more likely than fans with low altruism to evaluate the motive of a team’s CRM campaign as cause-oriented and show their support for the campaign.

1. Introduction

In today’s competitive marketplace, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is considered a crucial part of business management for a firm to ensure its survival and sustainability. CSR has developed into an important agenda, and its scope has expanded from responsible business to strategic decision-making [1]. A strategic approach to CSR is an effective and necessary competitive tool that can allow firms to ensure their survival and sustainable growth in a competitive market environment [2]. If social needs, environmental limits, and corporate interests are collectively well-orchestrated, firms can achieve competitive advantage and sustainable growth through CSR [3]. According to the 2014 Public Affairs Pulse Survey [4], 84% of U.S. consumers need more companies to be concerned about social issues and look forward to the company’s carrying out of actual social responsibility activities shortly. Another recent report found that more than half (55%) of global consumers surveyed were willing to pay extra for a company’s products and services if that company was committed to positive social and environmental impacts [5]. As a reflection of this, 75% of the 4900 companies in the world participate in corporate social responsibility and release annual reports that disclose their social responsibility activities to the general public [6].

However, as corporate social responsibility enters the phase of quantitative expansion, a question about its effectiveness has been raised [7]. Given this, Kotler and Lee [8] argued that a firm’s corporate social responsibility activity, which is combined with its marketing campaigns, serves as a desirable means by which the company can ensure its effectiveness. In other words, it is important to understand that a firm as a healthy corporate citizen in our society should consider both its social and traditional economic responsibilities to accomplish the effectiveness of its corporate social responsibility [9]. As a result, cause-related marketing (CRM) has emerged that intertwines the social and economic values of both stakeholders and firms [9].

CRM refers to a marketing activity that enables companies to carry out economic activities and realize social values through strategic alliances with social causes [7]. Per the cause-related marketing literature, CRM improves corporate image [10], fosters a positive brand attitude [11], and enhances customer loyalty [9]. Also, to increase the effectiveness of CRM, it is reported that consumers’ positive recognition of brand-cause fit and CRM motive should come first [9,12]. Particularly, consumers are more interested in why a company is doing a specific activity than in what the company is doing, so the consumers’ positive perceptions of motive for CRM campaigns is an important antecedent of CRM effectiveness [13].

Additionally, prior literature has suggested that consumers’ embedded altruism acts as a significant moderator of CRM effectiveness [14,15]. For example, Lavack and Kropp [14] reported that the higher the level of psychological involvement consumers have with a given charity, the higher the value of self-sufficiency, self-esteem, and positive relationships with others they have, which prompted the authors to conclude that altruism affects consumer attitude regarding a firm’s CRM. Vlachos [15] also claimed that altruism, an intrinsic characteristic of consumers, had a moderating effect on enhancing emotional attachment to a firm’s CRM campaign and purchase behaviors related to cause-related products. Collectively, altruistic consumers, as opposed to non-altruistic consumers, are more likely to be helpful to others and respond more positively to firms’ CRM campaigns via their purchase behaviors as they relate to cause-related products [16].

Meanwhile, the importance of CRM has been extended to the sport industry. As a means of emphasizing the need for the introduction of CRM campaigns in the professional sport sector, Lachowetz and Gladden [17] suggested that the implementation of CRM by professional sport teams could reverse the negative perceptions sport fans have regarding teams due to players’ banned drug use or player strikes and, in turn, could enhance favorable attitude and fan loyalty. The extant studies on CRM in professional sport revealed the consequences of CRM, such as elevated favorable attitude regarding teams [11,18], increased intention to purchase team-licensed products, and enhanced team loyalty [11,19,20]. The prior studies, however, seem to have limitations in considering sport fans’ embedded altruistic tendencies when it comes to the effectiveness of sport teams’ CRM campaigns. Moreover, despite its popularity as a research topic in the professional sport context, it seems that CRM has been studied primarily from the perspective of Western professional sports leagues [17,18,20]. A better understanding of the Korean case would shed light on the cross-cultural similarities and differences between Asian and Western sport consumer points of view regarding CRM. Therefore, the present study examined the influence of sport fans’ perceived CRM motive of a team on fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, and the moderating effects of sport fans’ altruism on the relationships among the constructs in the context of the Korean professional baseball league.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Korea Baseball Organization League

The Korea Baseball Organization (KBO) League, which is a professional baseball league in South Korea, was originally founded with six franchises in 1982 and has expanded to ten franchises. Nine of the ten franchises are named after the business conglomerates owning them, while one sold its naming rights in 2007. The KBO League is the most popular professional sport league in South Korea, and each team plays 144 games in a home-and-away format every regular season. The total number of professional baseball spectators reached 1.43 million in 1982 but exceeded 7.2 million in 2019. Also, the total sales of the KBO League rose from about $372 million in USD in 2015 to about $426 million in USD in 2017 [21]. According to the WBSC Baseball World Rankings reported by the World Baseball Softball Confederation, the KBO league ranks third after the Japanese Nippon Professional Baseball league and the United States Major League Baseball, proving that the KBO league is one of the leading professional baseball leagues in the world [22].

More importantly, as the Korean professional baseball industry grows, each KBO league team has been actively engaged in various CRM activities aimed at achieving sustainable growth and development with their sport fans. The CRM campaigns of the professional baseball teams in the KBO league consist primarily of three domains that support underprivileged individuals, foster future generations, and conduct community service through nonprofit organizations such as the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Save the Children [23]. One team donated the profit from preseason game tickets every season to the Save the Children fund. Another team initiated a CRM campaign that supports local underprivileged children by donating 3% of the tickets purchased by sport fans and 500 won per uniform purchase during a regular season. In particular, team A used in this study supports UNICEF’s School for Asia campaign by donating 100 won per sport fan who visits the stadium every season.

2.2. Cause-Related Marketing and Its Consequences

Cause-related marketing (CRM) is a firm’s marketing strategy that creates a favorable attitude and positive firm image, thereby strengthening its brand equity in a competitive market environment through a strategic tie with a social cause [24]. Today’s CRM began with American Express initiating a CRM campaign to fund the restoration of the Statue of Liberty, thus raising $1.7 million as consumers donated 1 cent to the fund for every purchase made [25]. Additionally, the National Football League (NFL), a leading professional sport league in the United States, has been actively involved in CRM to raise public awareness of breast cancer in association with the American Cancer Society [26]. Korean professional baseball teams have also initiated various CRM campaigns partnered with several social causes such as cheerleading, baseball, and mentoring classes for local youths and baseball day programs that provide an opportunity for the underprivileged to watch baseball games [27]. In conclusion, the CRM campaigns carried out by professional sport teams can be considered a promising means of communication that reinforces the sport teams’ brand equity [11].

Extant studies have reported that CRM motive perceived by consumers affects brand attitude [10,11]. Consumers, in general, tend to interpret a firm’s CRM campaign as a dichotomy of a cause-oriented or profit-oriented motive [12]. Barone et al. [10] reported that, on the premise that there is no difference in the quality of products, consumers are likely to show a more favorable attitude toward a firm’s CRM campaign that they perceive to have a cause-oriented motive than one they do not. Kim et al. [11] also emphasized that the motive of a professional sport team’s CRM has a positive effect on consumers’ attitude regarding the team. Similarly, Kim, Kim, and Han [28] argued that the higher the credibility of a CRM campaign perceived by consumers, the more positive the attitude regarding the cause-related brand. As a result, when consumers perceive that a company’s CRM campaign has a pure motive, it seems to have a positive impact on brand attitude. Thus, the following hypothesis was posited based on previous studies:

Hypothesis 1.

The CRM motive of a professional baseball team perceived by sport fans will have a positive effect on fan attitude regarding the team.

Additionally, CRM that a firm implements not only influences consumers’ positive attitude regarding the firm, but it also enhances their intentions to purchase the firm’s products [29]. The reason for consumers’ positive evaluations of cause-related products or products produced by a firm performing CRM is because of the moral satisfaction and emotional benefit by participating in good deeds that help others through their consumption behavior [30]. In this regard, Barone et al. [10] reported that when consumers perceive that a firm’s CRM participation is the result of motivations linked to the public interest, it has a positive effect on the consumers’ attitude regarding the firm and purchase intention related to its cause-related products. Additionally, Baek et al. [9] reported that the more millennial consumers perceived that CRM motives were cause-centered, the more positively they responded to purchase intention related to cause-related products. However, if consumers do not recognize the altruistic authenticity of a firm’s CRM participation or perceive it to be rooted in a firm-oriented motive, the firm’s participation may adversely affect consumer behavior, including with regard to brand attitude and purchase intention [9,31]. Collectively, consumers are interested in firms’ CRM campaigns being motivated by and linked to a cause. If consumers perceive that a firm’s CRM is motivated via the firm’s benefit rather than via public interest, they not only negatively evaluate the CRM campaign, but they also negatively respond to its brand and products [32,33]. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The CRM motive of a professional baseball team perceived by sport fans will have a positive effect on purchase intention related to team-licensed products.

Attitude refers to the degree of a positive or negative assessment of a particular entity [34]. The theory of reasoned action suggests that a positive attitude toward a brand is, in fact, an indicator of the ultimate purchase decision rather than simply an internal evaluation of the brand [35]. Particularly, prior research on consumer behavior has revealed that attitude is a crucial part of marketing practice, because how consumers assess products is significantly associated with what consumers will purchase in the marketplace [36]. More importantly, the majority of the cause-related marketing research constructed consumer attitude as an important predictor of purchase intention [11,37,38]. For example, Kim et al. [11] reported that professional sport fans’ attitude regarding a team had a significantly positive impact on re-attendance intention and the complete mediating role between sport fans’ perceptions of CRM and re-attendance intention. Thus, we developed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Fan attitude regarding a professional baseball team will have a positive effect on purchase intention related to team-licensed products.

2.3. Moderating Effects of Altruism

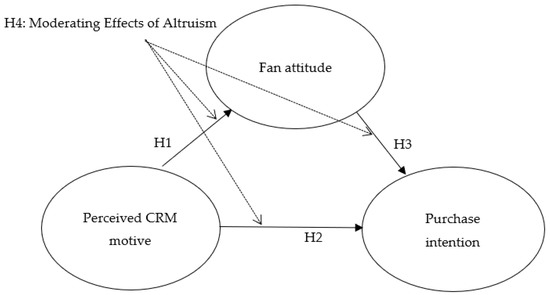

Altruism is a psychological trait via which individuals help others without seeking or receiving any external rewards, and it serves as a significant motivator behind volunteer work that provides aid to others [39]. In the context of cause-related marketing, altruism is considered a key factor in encouraging consumers to support social causes and to become socially responsible society members [40]. Given this, Patel et al. [38] found that, when consumers have a positive attitude regarding a brand that realizes CRM, they show high purchase intention related to the brand, and the link between brand attitude and purchase intention becomes stronger if the consumers are more involved with the cause. Gupta and Pirsch [16] also stressed that when consumers perceive that a brand has an altruistic motivation to link with a social cause, their desire to support the social cause becomes much stronger, and this, in turn, allows for the consumers to assume positive attitude regarding the sponsoring brand. Collectively, it seems that consumers’ embedded altruism moderates the effects of CRM on attitude and purchase intention [16,38]. Thus, based on the previous studies, we proposed the following hypothesis (see also Figure 1 for the research model):

Figure 1.

Research Model. CRM: cause-related marketing.

Hypothesis 4.

The embedded altruism of sport fans will have a positive moderating effect on the relationships among a perceived professional baseball team’s CRM motive, fan attitude, and purchase intention related to team-licensed products.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Data Collection Procedures

We collected data from spectators who attended a Korean professional baseball game in August 2019. Six well-trained surveyors spread out into the baseball stadium and collected data from the spectators waiting for the game to begin at the stadium seats, hallways, and concession areas. The surveyors confirmed that spectators had attended at least one live professional baseball game during the prior 12-month period and intended to participate in the study before distributing a written consent form. After acquiring their written consent to participate in the study, the surveyors asked the participants to carefully read a written stimulus about the CRM program of team A, which was used in the current study, that has been implemented (in Korea). After carefully reading the stimulus, the participants were asked to answer the survey items using a self-administered method.

The stimulus, which was presented on the first page of the survey, provided information about the CRM campaign of team A, which supported the School for Asia project via an alliance with UNICEF, which is a United Nations agency responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to children worldwide. More specifically, the following information was included in the stimulus:

Team A has signed an agreement with UNICEF to support the School for Asia project and promote 100 million won (US $84,000) by donating 100 won per sport fan who visits the stadium for this season. Launched in 2012, UNICEF’s School for Asia is a global project that is designed to provide education for children in the Asia-Pacific region, including Nepal, India, Laos, and Mongolia. The program provides school buildings, teaching materials, and life skills education focusing on good health, nutrition, and HIV prevention education for children who do not have learning opportunities due to poverty and social discrimination.

As a result, 166 survey questionnaires were collected. After eliminating two responses with no more than three questions answered, we included a total of 164 responses in the present study. Of the respondents, 113 participants (68.9%) were male, and 51 participants (31.1%) were female. A majority of the participants (48.2%) were between the ages of 30 and 39 years and had graduated from college (69.5%). Moreover, 31.7% of the participants reported monthly incomes of between $3,000 and $4,999, and 30.5% were office workers. Table 1 shows a summary of demographics.

Table 1.

Demographics of Participants.

Regarding the sample size of 166 used in the current study, we followed recommendations from Hair et al. [41], who suggested that a minimum sample size for a structural model containing less than 7 constructs, moderate communalities, no missing value, and no underidentied constructs is 150. Given the suggested conditions, our sample size of 164 is deemed adequate.

3.2. Instruments

A total of 17 question items, with the exception of five demographic characteristics (i.e., gender, age, education, occupation, and monthly income), were adapted from previous studies and were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Since the original scales were developed in English, we used back-translation based on Brislin’s guideline [42]. A bilingual individual who speaks fluent English and Korean translated the original question items into Korean, then a Korean scholar who also speaks fluent English back-translated the translated version into English. No discrepancies between the translated and back-translated versions were found.

Specifically, we adapted three items to measure baseball fans’ perceived CRM motive from Baek et al. [9]. Three items to measure fan attitude were adapted from Kim et al. [11]. We used two modified items measuring purchase intention related to team-licensed products from Baek, Kim, Kim, and Byon [43]. Four items to measure altruism were adapted from Rushton, Chrisjohn, and Fekken [44]. The specific survey items of altruism, which is the general tendency of sports fans, in this case, to help others and their altruistic actions related to charity, included “I have given money to a charity”, “I have donated goods or clothes to a charity,” “I have done volunteer work for a charity,” and “I have bought charity-related products deliberately because I knew it was a good cause.”

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Before examining the research hypotheses, we conducted descriptive statistical analyses, which revealed the skewness (ranging from −0.53 to −0.68) and kurtosis (ranging from 0.47 to 0.56) values within the acceptable ranges [41]. Tolerance (ranging from 0.36 to 0.67) and variance inflation factor (ranging from 1.50 to 2.80) values were assessed to check multicollinearity, and the results revealed that multicollinearity was not a concern [41]. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations. We conducted a descriptive analysis using SPSS 23.0.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Variables.

4.2. Assessing Common Method Variance

As we collected single-sourced and self-reported data, it was necessary to test common method variance (CMV), which is defined as “variance that is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the constructs the measures represent” [45]. As independent variables and a dependent variable were collected from the same self-reported source (i.e., spectators) simultaneously, the relationship between independent variables and a dependent variable might be inflated. To examine CMV, we employed Harman’s single-factor method [45]. To conduct this test, we ran principal component analysis (PCA) with no rotation of factor axes. The results presented that a total of 29.6% of the variance was explained via a single factor. The variance is significantly less than the criterion of 50% of the total variance. Hence, CMV is not a concern [46,47]. Sport management scholars have begun to recognize the potential negative effects of CMV and have addressed it using procedural (e.g., dyadic analysis [48]) and statistical remedies (e.g., Harman’s single-factor method, an unmeasured latent method factor technique [45,46,47,48,49,50]).

4.3. Measurement Model Test

Using Amos 23.0, we also tested the measurement model via a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which indicated an acceptable model fit (χ² = 17.04, df = 17, p = 0.45, χ²/df = 1.00, goodness-of-fit index [GFI] = 0.97, root-mean-square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.01, and standardized root-mean-square residual [SRMR] = 0.01) [51]. Composite reliability (CR) values (ranging from 0.81 to 0.91) and average variance extracted (AVE) values (ranging from 0.70 to 0.77) demonstrated good convergent validity [50]. All AVE values were higher than the squared correlation of all configuration pairs, which ensures discriminant validity [51] (see factor loadings in Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor Loadings (λ), Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

4.4. Structural Model Test

As presented in Table 4, the results of structural equation modeling (SEM) reveal an adequate model fit to the data, χ² = 17.04, df = 17, p = 0.45, χ²/df = 1.00, GFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.01, and SRMR = 0.04. Additionally, perceived CRM motive had a significant positive impact on fan attitude (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and purchase intention related to team-licensed products (β = 0.33, p < 0.01), and fan attitude also had a significant positive effect on purchase intention (β = 0.22, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Path Coefficients between CRM Motive, Fan Attitude, and Purchase Intention.

In order to examine whether fan attitude mediates the relationship between sport fans’ perceived CRM motive and purchase intention, a mediation test was conducted using a bias-corrected bootstrap based on 5000 resamples [52]. As shown in Table 5, fan attitude (β = 0.07, p < 0.05, CI = 0.01 to 0.21) values significantly mediated the relationship between sport fans’ perceived CRM motive and purchase intention related to team-licensed products.

Table 5.

The Results of Mediating Effects of CRM Motive.

Additionally, we tested the moderating effects of sport fans’ altruism in the proposed model. Because the sport fans’ altruism was a continuous latent construct, we created interaction terms in order to employ the product indicator approach. Following Chin, Marcolin, and Newsted [53], we generated cross products by multiplying each indicator of the independent variable with each indicator of the moderator variable. All independent variables and moderator were mean-centered. As a result, a moderating effect of sport fans’ altruism was found on the relationship between fan attitude and purchase intention (β = 0.28, p < 0.05) and CRM motive and purchase intention (β = 0.23, p < 0.05). The results indicate that the relationship between fan attitude and purchase intention becomes stronger with high levels of altruism. Similarly, among fans possessing high altruism, as opposed to fans with low levels of altruism, the relationship between CRM motive and purchase intention is stronger.

However, a moderating effect of altruism on the relationship between CRM motive and fan attitude was not found to be significant (β = 0.15, p = 0.372), indicating that fans’ levels of altruism do not make a difference regarding the relationship that exists between CRM motive and fan attitude for fans.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the effects of sport fans’ perceived CRM motive on fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, and how the sport fans’ altruism moderates the relations among the constructs in the context of the Korean professional baseball league. As expected, the findings of the present study revealed that sport fans’ perceived CRM motive had a significant impact on fan attitude and is well supported by the previous studies [11,37,38] reporting that the perceptions of CRM significantly influenced consumers’ attitude regarding brands. More specifically, Patel et al. [38] found that consumers have more favorable attitude regarding a firm carrying out a CRM program than a firm that does not. Beak et al. [9] also reported that as millennials perceive a firm’s motive for participating in a CRM campaign, they are likely to feel positive regarding the firm, and the authors concluded that millennial consumers’ perceptions of a cause-centered motive for a CRM program are crucial to its effectiveness. It seems plausible that when the motive of a sport team’s CRM is perceived as altruistic rather than profit-oriented, sport fans are likely to believe that the team is trying to give back to their home communities and encourage favorable attitude regarding the team, affecting their inferences that help to build positive purchase intention [18].

The study also found that sport fans’ perceived CRM motives had a significant effect on purchase intention related to team-licensed products, replicating previous studies indicating that a firm’s cause-centered CRM motive, as perceived by consumers, can positively impact consumer choice [9,11]. However, Strahilevitz and Myer [54] reported that charity incentives are more effective for frivolous products, where consumers make easier trade-offs (e.g., cheaper products) than real products when responding to CRM programs. Barone et al. [10] also found that trade-offs between price or quality and a social cause can be more difficult for product categories with high economic risks than cheaper product categories. Thus, our findings suggest that the perceived motive behind CRM can be one of the most crucial attributes in sport consumer decision-making, demonstrating that sport fans are willing to trade off other attributes to support a team’s CRM campaign.

In line with the findings of previous researchers [11,19,38], sport fans’ attitude regarding a team were found to have a significant impact on purchase intention related to team-licensed products. Moreover, the findings of the present study also revealed that fan attitude was a significant mediator between perceived CRM motive and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, and this was well-supported by Kim et al.’s study [11]. According to Fishbein and Ajzen [35], an individual’s overall attitude regarding a certain object is determined by the subjective value or evaluation of the object. Moreover, behavioral intention, which is the immediate antecedent of behavior, is formulated by attitude regarding a certain object. It is plausible that when sport fans are exposed to team-initiated CRM, they are likely to evaluate the CRM based on the given information (i.e., purpose, duration, beneficiaries, and potential benefits for the team and fans) and their values (i.e., genuine motive). As sport fans positively evaluate the CRM whose motive is public-centered, they are likely to develop favorable attitude regarding the team and purchase intentions related to team-licensed products.

Lastly, the present study also revealed that sport fans’ altruism had moderating effects on the relationships between perceived CRM motive and purchase intention and fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products. The findings are consistent with the previous studies [16,32,37,38]. For example, Myers and Kwon [32] found that consumers’ involvement in a cause positively affected attitude regarding CRM. Hajjat [37] also reported that consumers’ cause involvement had significant moderating effects on attitude regarding an advertisement and a brand and purchase intention. One possible explanation is provided via the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), which suggests that individuals who are heavily involved in CRM programs exhibit higher cognitive elaboration than those who are not [55]. These individuals, as opposed to those who are not altruistic, go through a more intensive assessment process to determine whether the CRM activities undertaken by a firm are rooted in genuine social concern, a business strategy, or a mere legal fulfillment [13]. It is also reported that a CRM program is effective only when a firm’s cause-exploitable motive is disguised [12].

Moreover, individuals with higher levels of psychological involvement with social issues are likely to value self-sufficiency, self-esteem, warm relationships with others, and a sense of belonging, all of which lead to positive attitude regarding CRM [14]. An individual’s high involvement with social issues is the result of prior experience with a CRM program, in which the individual finds that the program and the cause-related products are personally important and relevant [38]. Likewise, it seems plausible that high altruistic sport fans, as opposed to low altruistic sport fans, are likely to go through a deeper assessment of the motive behind a sport team’s CRM campaign. If the evaluation of the motive behind a CRM campaign suggests that it is public-centered rather than team-centered, altruistic sport fans, as opposed to fans with low altruism, are more likely to feel that a team’s CRM effort is personal and meaningful for themselves, which will enhance favorable attitude regarding the team as well as purchase intention related to team-licensed products.

From a practical standpoint, the findings of the present study indicate that the motive behind a sport team’s CRM is an important predictor of sport consumption behavior. In particular, the current study revealed that a significant impact of the perceived motive behind CRM on the sport fans’ consumption of team-licensed products was a direct outcome of CRM. Thus, the findings of this study provide sport teams’ marketing managers with the rationale as to the effectiveness of implementing CRM. Moreover, the present study pointed out that when highly altruistic sport fans evaluate a team’s CRM as being more altruistic, favorable attitude regarding the team and improved purchase intention related to team-licensed products are likely to result. If a sport team hopes to ensure the effectiveness of a CRM campaign, it might be necessary to consider sport fans’ embedded characteristics. As suggested in the present study, professional sport teams’ marketers should provide sport fans—especially fans with high altruism—with all key information about their CRM campaigns, including information related to purpose, duration, beneficiary groups, and potential benefits for the fans and the teams, as this can help to lessen altruistic sport fans’ perceptions that CRM campaigns are profit-centered.

6. Conclusions

In the professional sport context, CRM is increasingly valued as a strategic marketing measure for a sport team’s sustainable development and for addressing social issues. A distinctive feature of CRM is that, unlike other traditional forms of marketing campaigns, firms can achieve a competitive advantage and sustainable growth through sports fans’ emotional commitment. However, there is little evidence that addresses the effectiveness of CRM when the levels of sport fans’ embedded psychological characteristics associated with helping others are considered. The present study aimed to investigate the influence of sport fans’ perceived CRM motive of a sport team on fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, and the moderating effects of sport fans’ altruism on the relationships among these variables in the context of the Korean professional baseball league.

The findings of the current study showed that sport fans’ perceived CRM motive significantly affected fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, and fan attitude also had a significant impact on purchase intention. Moreover, sport fans’ altruism had significant moderating effects on the relationships between perceived CRM motive and purchase intention, as well as team attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products. Consequently, the present study demonstrates that professional sport fans with high altruism are more likely than fans with low altruism to evaluate the motive behind a team’s CRM campaign as cause-oriented and show their support for the campaign.

Meanwhile, several limitations of the current study should be addressed. First, this study used professional baseball fans in South Korea to examine the influence of a sport team’s CRM program on fan attitude and purchase intention related to team-licensed products, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, it may be appropriate to conduct a future study with a population of sport fans associated with other professional sports and possibly sport fans in other countries to enhance the external validity of the tested model. Second, the present study did not consider sport fans’ emotional attachments to a sport team, possibly masking the moderating effects of sport fans’ altruism on the relationships among the constructs in the current study. Thus, careful interpretation should be considered. It is also suggested that if the study is replicated, it may be appropriated to control this variable.

Another limitation concerns endogeneity bias. In survey-based research with cross-sectional data, the conclusion may not be free from endogeneity, which refers to “an explanatory variable correlating with the disturbance term of the regression equation and not accounting for it will likely result in biased parameter estimates that undermine the validity of the findings obtained from regression-type analyses of observational data” [56]. To address this limitation, researchers should collect data at multiple points in time. For instance, variables of CRM motive should be collected first, followed by the mediator (i.e., fan attitude), and purchase intention (i.e., dependent variable).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-y.B.; methodology, W.-y.B., K.K.B., H.-s.S., D.-H.K.; formal analysis, W.-y.B., K.K.B.; data curation, W.-y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, W.B.; writing—review and editing, W.-y.B., K.K.B., H.-s.S., D.-H.K.; supervision, K.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zahidy, A.A.; Sorooshian, S.; Hamid, A.; Hamid, Z.A. Critical Success Factors for Corporate Social Responsibility Adoption in the Construction Industry in Malaysia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Ladero, M.M.; Galera-Casquet, C.; Valero, V.; Méndez, M.J.B. Sustainable, Socially Responsible Business: The Cause–Related Marketing Case. A Review of the Conceptual Framework. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2013, 2, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad-Segura, E.; Cortés-García, J.F.; Belmonte-Ureña, J.L. The Sustainable Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility: A Global Analysis and Future Trends. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Affairs Council. Public Affairs Pulse Survey. 2014. Available online: http://pac.org/pulse/?p=298 (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Nielsen Global Research. Doing Well by Doing Good. 2014. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/report/2014/doing-well-by-doing-good/ (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- KPMG. The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017: The Road Ahead. 2017. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2017/10/kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2017.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Brønn, P.S.; Vrioni, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Cause-Related Marketing: An Overview. Int. J. Advert. 2001, 20, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, W.; Byon, K.K.; Choi, Y.; Park, C. Millennial Consumers’ Perception of Sportwear Brand Globalness Impacts Purchase Intention in Cause-Related Product Marketing. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2017, 45, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Miyazaki, A.D.; Taylor, K.A. The Influence of Cause-Related Marketing on Consumer Choice: Does One Good Turn Deserve Another? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kwak, D.; Kim, Y. The Impact of Cause-Related Marketing (CRM) in Spectator Sport. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.J.; Norman, A.T.; Miyazaki, A.D. Consumer Response to Retailer Use of Cause-Related Marketing: Is More Fit Better? J. Retail. 2007, 83, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertiwi, A.L.; Balqiah, E.T. How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative: Cause-Related Marketing vs. Philanthropy. Asean Mark. J. 2016, 8, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lavack, A.M.; Kropp, F. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Consumer Attitudes toward Cause-Related Marketing. Soc. Mark. Q. 2003, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, A.P. Corporate Social Responsibility and Consumer-Firm Emotional Attachment: Moderating Effects of Consumer Traits. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1559–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Pirsch, J. A Taxonomy of Cause-Related Marketing Research: Current Findings and Future Research Directions. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2006, 15, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowetz, T.; Gladden, J. A Framework for Understanding Cause-Related Sport Marketing Programs. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2003, 4, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.R.; Graeff, T.R. Consumer Attitude toward Cause-Related Marketing Campaigns. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 57, 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Cianfrone, B.; Byon, K.K.; Schoenstedt, L. Examination of the Relationships among Values, Identification, Involvement, Perceived Product Attributes towards the Purchase of Team Licensed Merchandise. Int. J. Sport Manag. 2010, 11, 517–540. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Ferreira, M. Cause-related marketing: The Role of Team Identification in Consumer Choice of Team Licensed Products. Sport Mark. Q. 2011, 20, 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W. Professional Baseball Sales Exceeding 500 Billion Won with 10 Million Spectators. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/22823755 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- World Baseball Softball Confederation. WBSC Baseball & Softball World Rrankings. Available online: https://rankings.wbsc.org/ (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Lee, Y. Let’s Show off Our Team. Colorful Pro-baseball Teams’ Social Contribution! Available online: http://www.mediasr.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=35708 (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Cone, C.L.; Feldman, M.A.; DaSilva, A.T. Causes and Effects. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Adkins, S. Cause Related Marketing: Who Cares Wins; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, S.B.; Cobbs, J.; Raska, D. Featuring the Hometown Team in Cause-Related Sport Marketing: A Cautionary Tale For League-Wide Advertising Campaigns. Sport Mark. Q. 2016, 25, 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, W.; Kim, B. The Structural Relationships between the Attributes of Cause-Related Marketing (CRM), Team Image, and Parent Company Image in the Korean Professional Baseball League. Korean J. Phys. Educ. 2015, 54, 223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Han, W. The Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Company and Brand Attitude. Seoul J. Bus. 2005, 11, 83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pracejus, J.W.; Olsen, G. The Role of Brand/Cause Fit in the Effectiveness of Cause-Related Marketing Campaigns. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Donations to Corporate-Supported Nonprofits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, K.E. Corporate Sponsorships of Philanthropic Activities: When Do They Impact Perception of Sponsor Brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.; Kwon, W.-S. A Model of Antecedents of Consumers’ Post Brand Attitude upon Exposure to a Cause-Brand Alliance. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2012, 18, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. A Typology of Consumer Responses to Cause-Related Marketing: From Skeptics to Socially Concerned. J. Public Policy Mark. 1998, 17, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory Of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Foxall, G.; Goldsmith, R.; Brown, S. Consumer Psychology for Marketing, 2nd ed.; The Alden Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjat, M.M. Effect of Cause-Related Marketing on Attitudes and Purchase Intentions: The Moderating Role of Cause Involvement and Donation Size. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2003, 11, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.D.; Gadhavi, D.D.; Shukla, S.Y. Consumers’ Responses to Cause Related Marketing: Moderating Influence of Cause Involvement and Skepticism on Attitude and Purchase Intention. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2017, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, J.C.; Sujan, H. Volunteer Behavior: A Hierarchical Model Approach for Investigating Its Trait and Functional Motive Antecedents. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomaviciute, K.; Bzikadze, G.; Cherian, J.; Urbonavicius, S. Cause-Related Marketing as a Commercially and Socially Oriented Activity: What Factors Influence and Moderate the Purchasing? Commer. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, W.-Y.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.-H.; Byon, K.K. The Impacts of the Perceived Golf Course Brand Globalness on Customer Loyalty through Multidimensional Perceived Values. Sustainability 2020, 12, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, J.P.; Chrisjohn, R.D.; Fekken, G.C. The Altruistic Personality and the Self-Report Altruism Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1981, 50, 1192–1198. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Bateman, T.S. Cynicism in the Workplace: Some causes and effects. J. Organ. Behav. 1997, 18, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, P.S.; Gencturk, E.F. International Principal—Agent Relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Byon, K.K. A Mechanism of Mutually Beneficial Relationships between Employees and Consumers: A Dyadic Analysis of Employee–Consumer Interaction. Sport Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.A.; Byon, K.K.; Baek, W. Customer-to-Customer Value Co-Creation and Co-Destruction in Sporting Events. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.W.; Byon, K.K.; Huang, H. Service Quality, Perceived Value, and Fan Engagement: Case of Shanghai Formula One Racing. Sport Mark. Q. 2019, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, E.P.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to Charity as Purchase Incentives: How Well They Work May Depend on What You Are Trying to Sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Issue Involvement can Increase or Decrease Persuasion by Enhancing Message-relevant Cognitive Responses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1915–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sande, J.B.; Ghosh, M. Endogeneity in Survey Research. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2018, 35, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).