The Tipping Point in the Status of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Research? A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Questions

RQ1: Has academic research been more focused on CSR and sustainability than on the role of consumers and their socially responsible behavior?

RQ2: To what extent is SRCB a developed or fragmented theme in the academic literature?

RQ3: What other themes are linked to SRCB research?

RQ4: How have these themes evolved since 1991?

RQ5: What are the most important themes and subject areas in terms of academic output?

3. Methodology

3.1. Bibliometrics and Co-Word Analysis Procedure

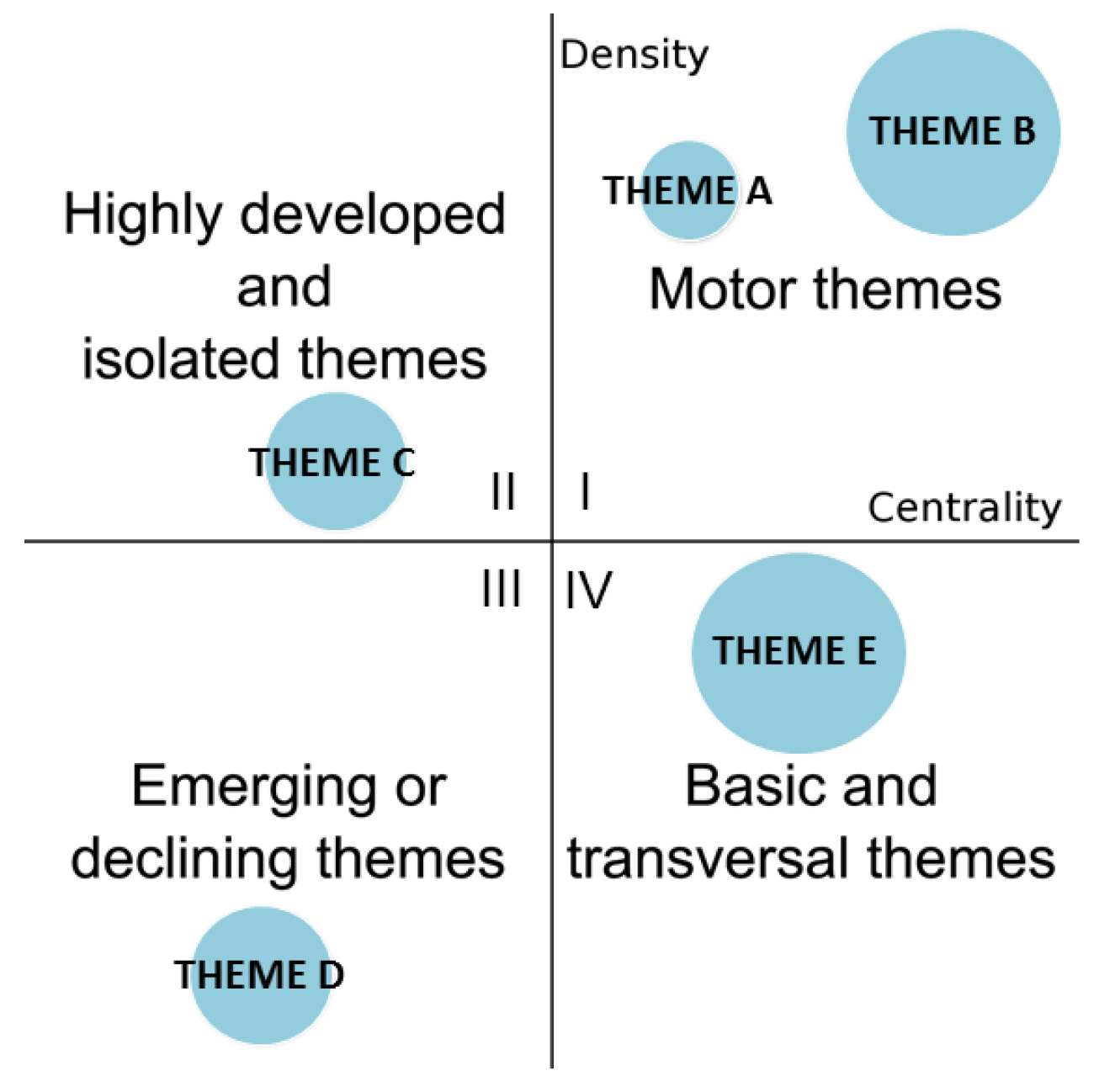

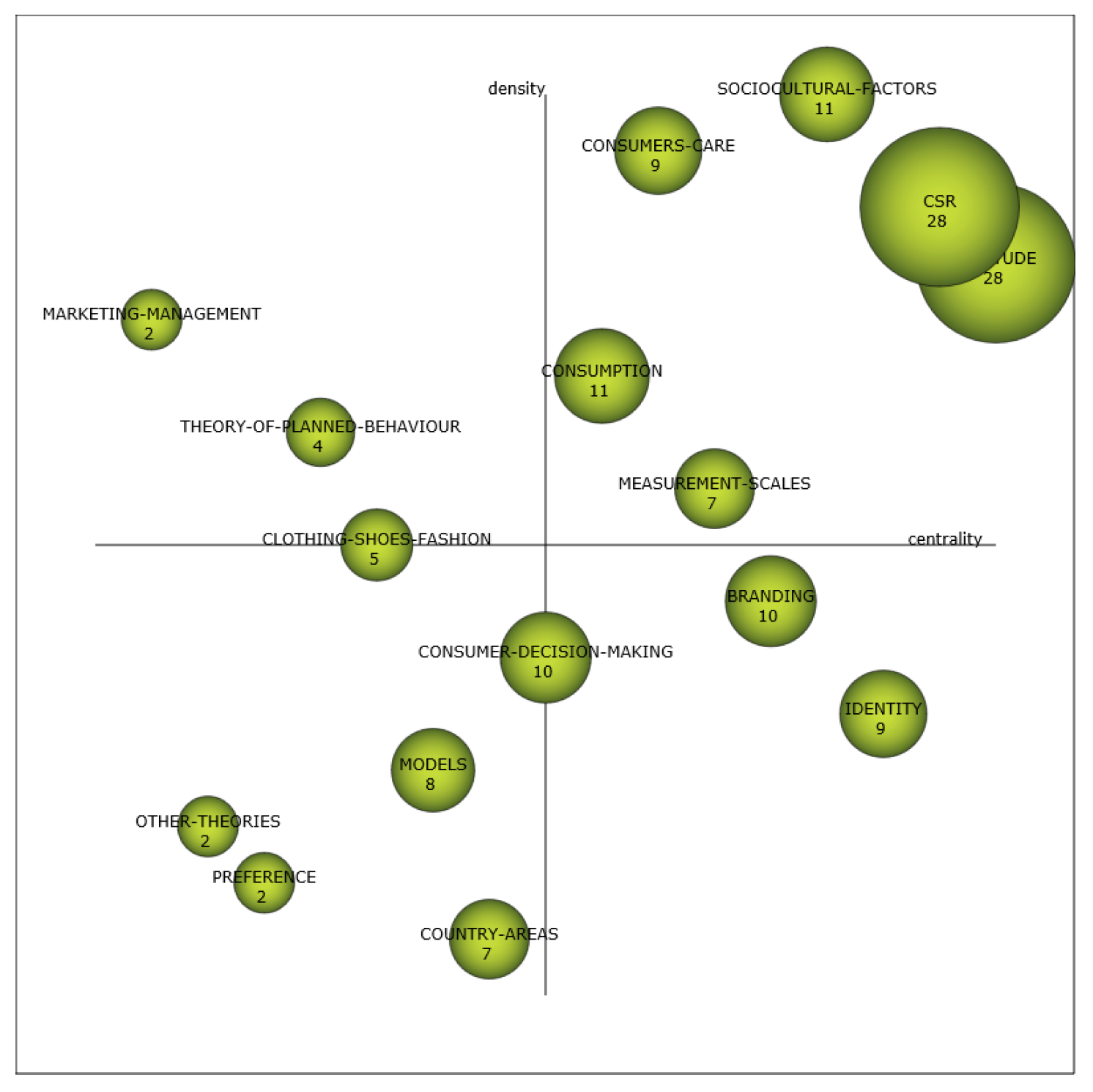

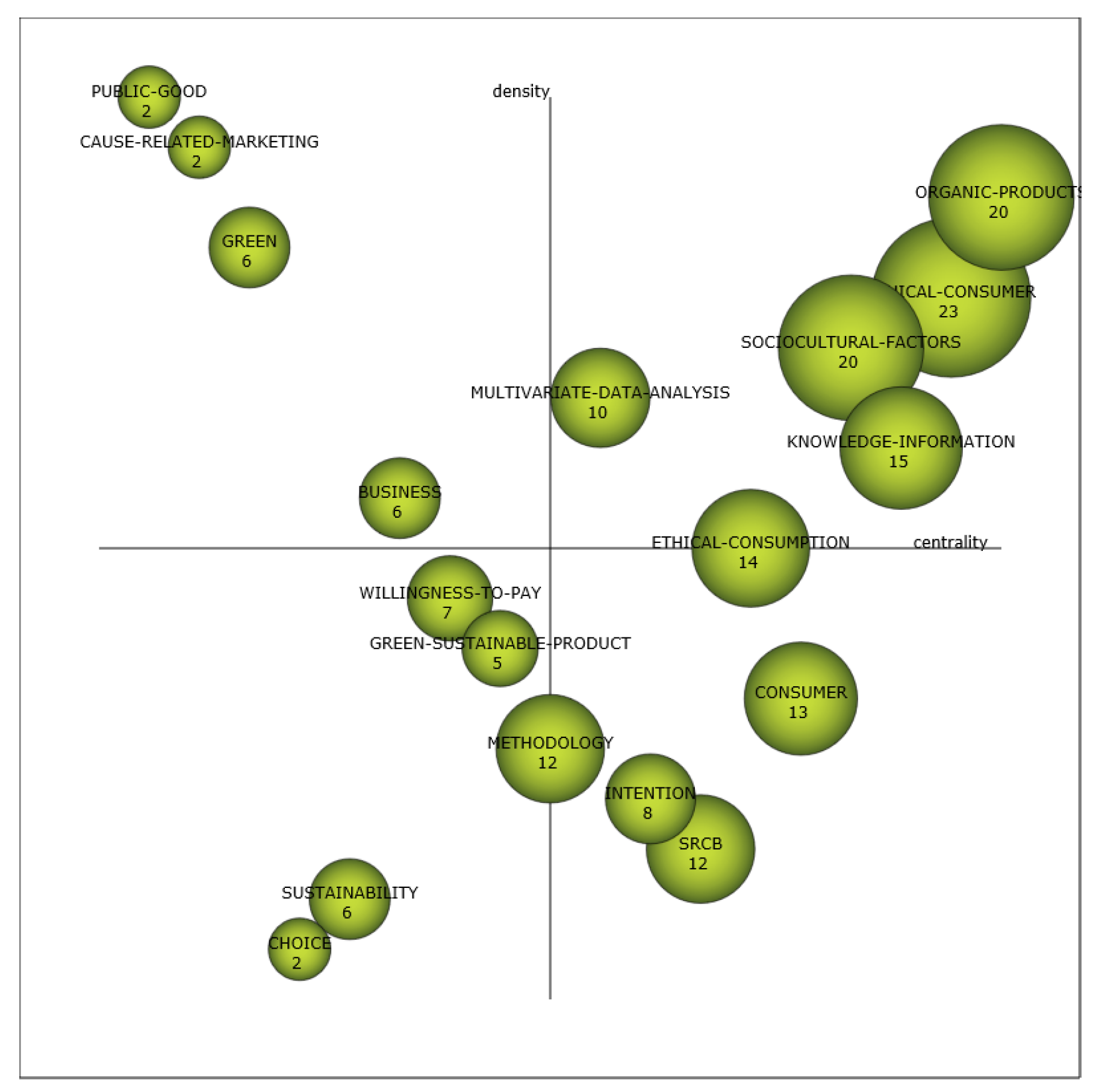

- Centrality: This measures the degree of interaction among clusters (or themes, topics); that is, the strength of the external links that exist among clusters. This value can be understood as a measure of the importance of a theme in the development of the entire field of research under analysis.

- Density: This measures the internal strength of a cluster; that is, the strength of the internal links between the keywords that describe this research topic. This value can be considered as a measure of the degree to which the topic under study has been developed.

- Themes in the upper right-hand quadrant (I) can be considered well-developed and important for the structuring of the research field in question. These are known as the “motor themes” of the specialist topic, as they have strong centrality and high density. In everyday parlance, we might call these mainstream themes.

- Themes in the upper left-hand quadrant (II) present highly developed internal links, but their external links are irrelevant, hence they are considered of only marginal importance for the research area. These themes are extremely specialized and peripheral in nature.

- Themes in the lower left-hand quadrant (III) are marginal and underdeveloped. They present low levels of density and centrality, and mainly pertain to emerging or declining themes.

- Themes in the lower right-hand quadrant (IV) are stable. That is, they are important to the research field in question, but they are not developed. They can be classified as transversal, basic (general) themes.

3.2. Data Collection

4. Analysis of Results

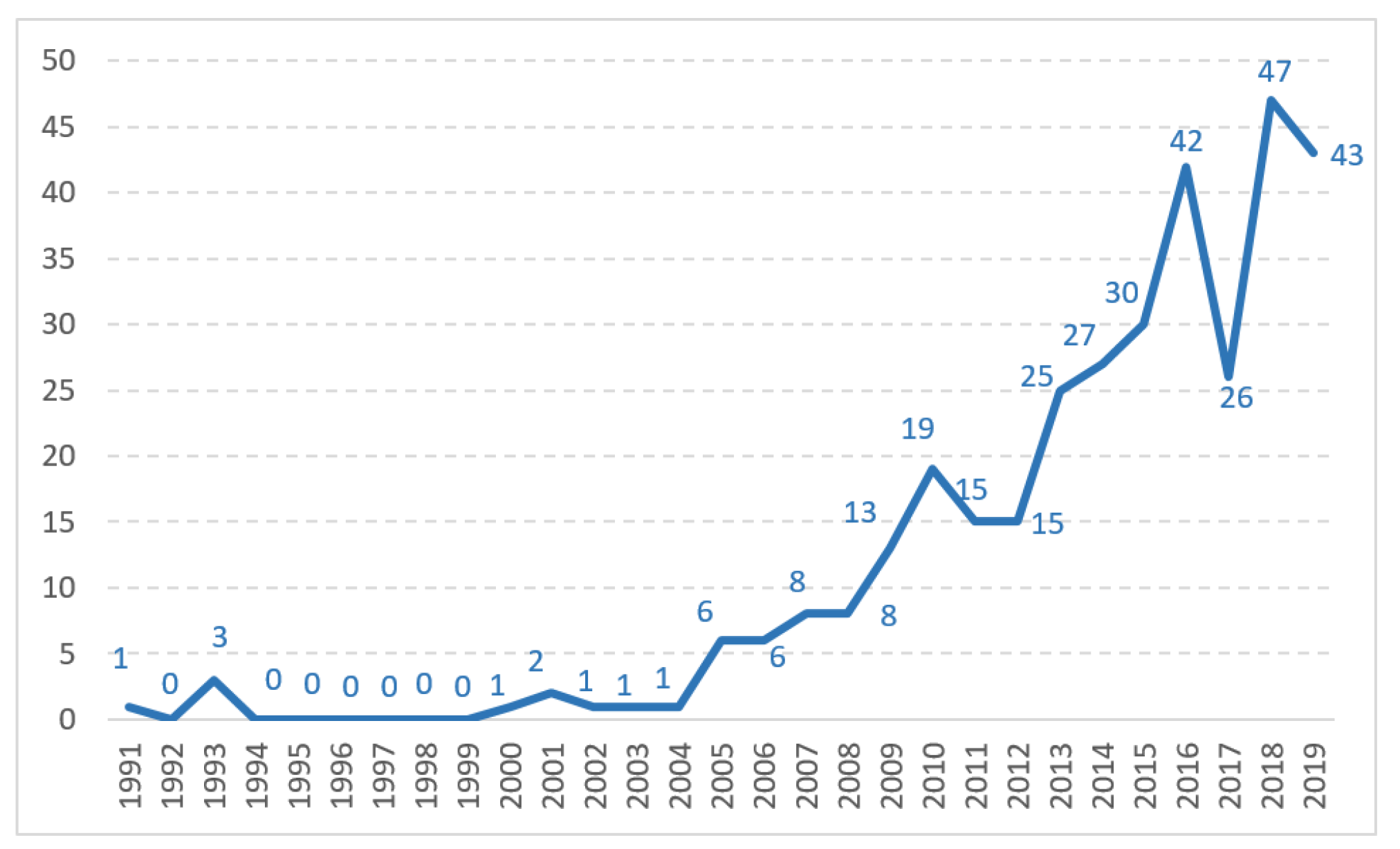

4.1. SRCB Literature Publication Activity: The Most Prolific Authors and Journals

4.2. Conceptual Evolution of SRCB

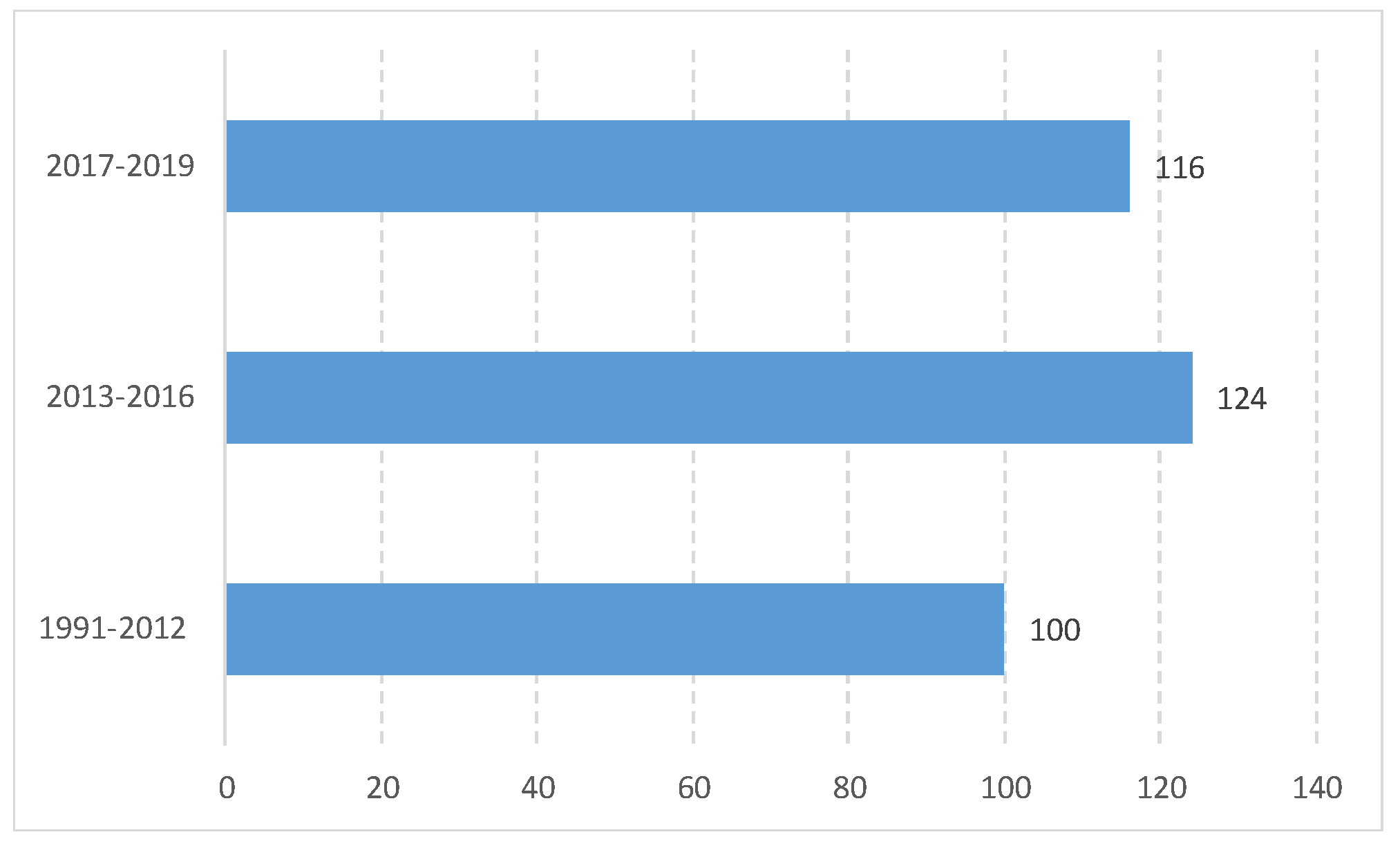

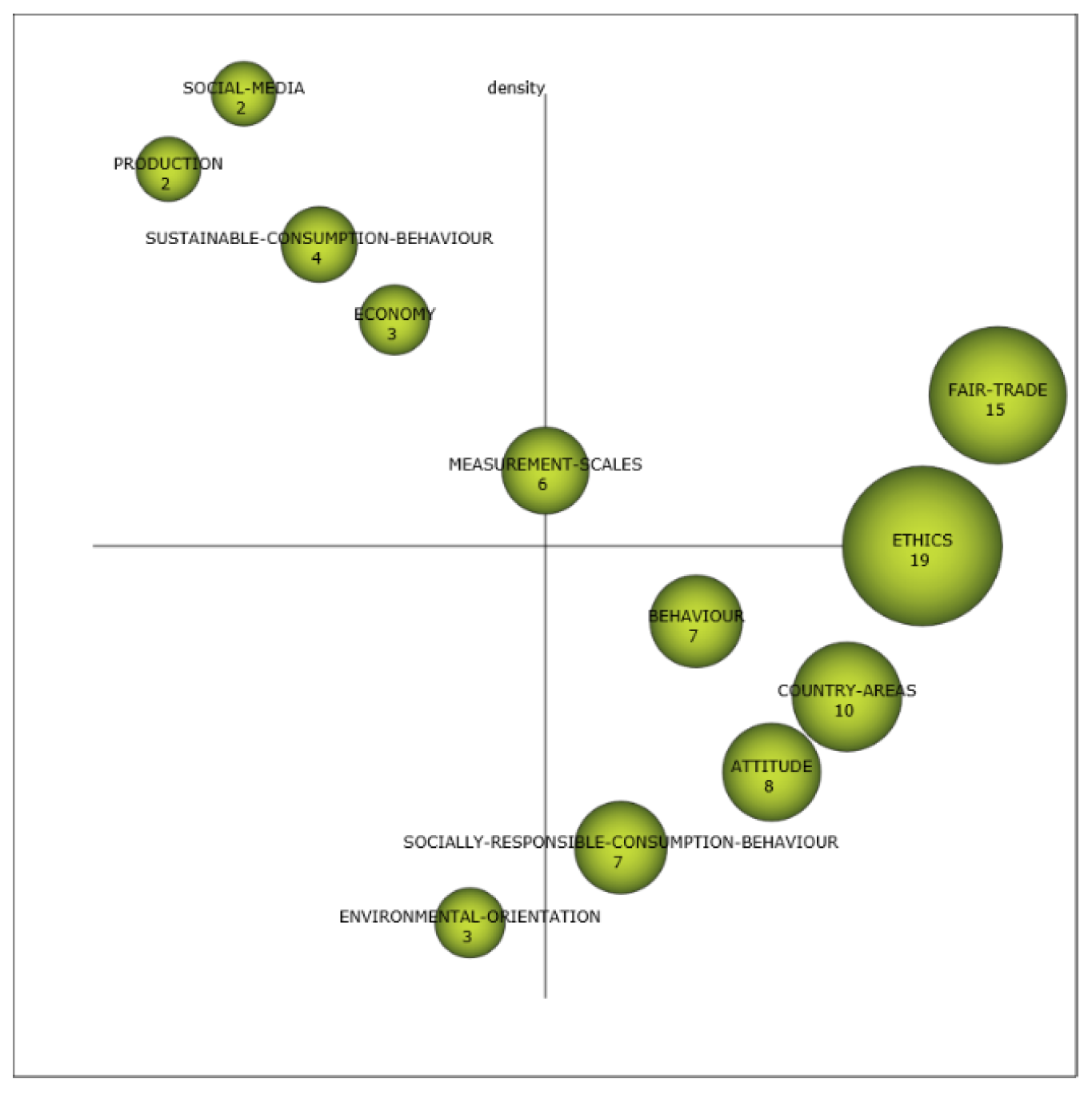

4.2.1. 1991–2012

4.2.2. 2013–2016

4.2.3. 2017–2019

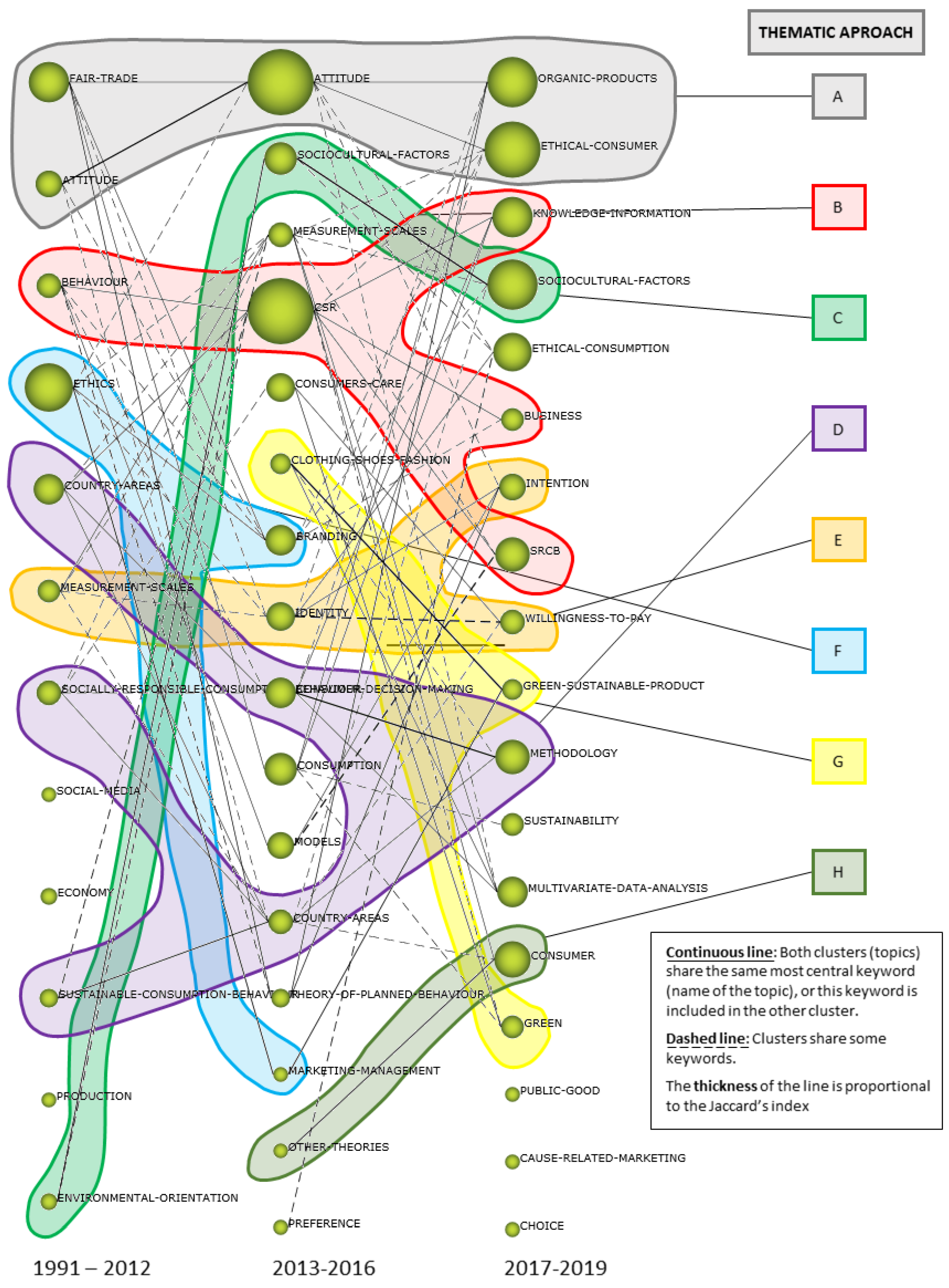

4.3. Structural Analysis of the Evolution of Research Dealing with SRCB

- Research on consumers’ attitudes towards ethical consumption. The theme “attitude” showed significant cohesion throughout the period, including in its structural evolution topics such as “fair trade”, “organic products”, and “ethical consumer”. It should be emphasized that all the concepts of this approach are motor issues in their corresponding time periods.

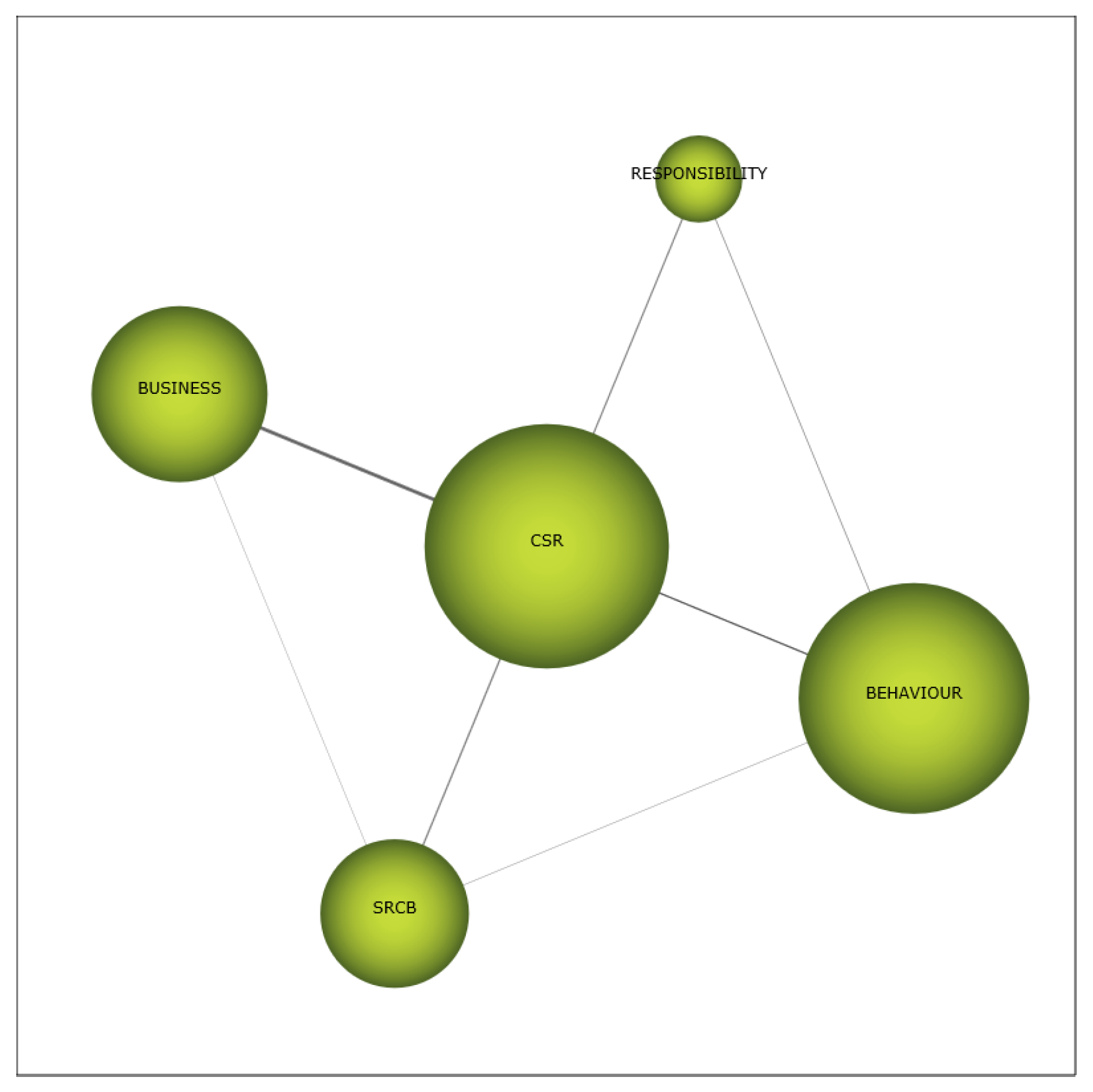

- Research on CSR. A second approach that clearly emerged is what we can call “CSR”, which includes “behavior”, “knowledge and information”, “business”, and “SRCB”. In this case, “CSR” and “knowledge and information” are motor issues in their respective periods. The volume of documents on the two themes (Table 1) that shape the two identified approaches shows that both approaches will contribute significantly to the development of SRCB research.

- Research on sociocultural factors under the auspices of environmental orientation. This may be the most concrete thematic area among these less established approaches, which include topics such as “environmental orientation” and “sociocultural factors”. In particular, “sociocultural factors” was a motor theme in the second and third periods analyzed.

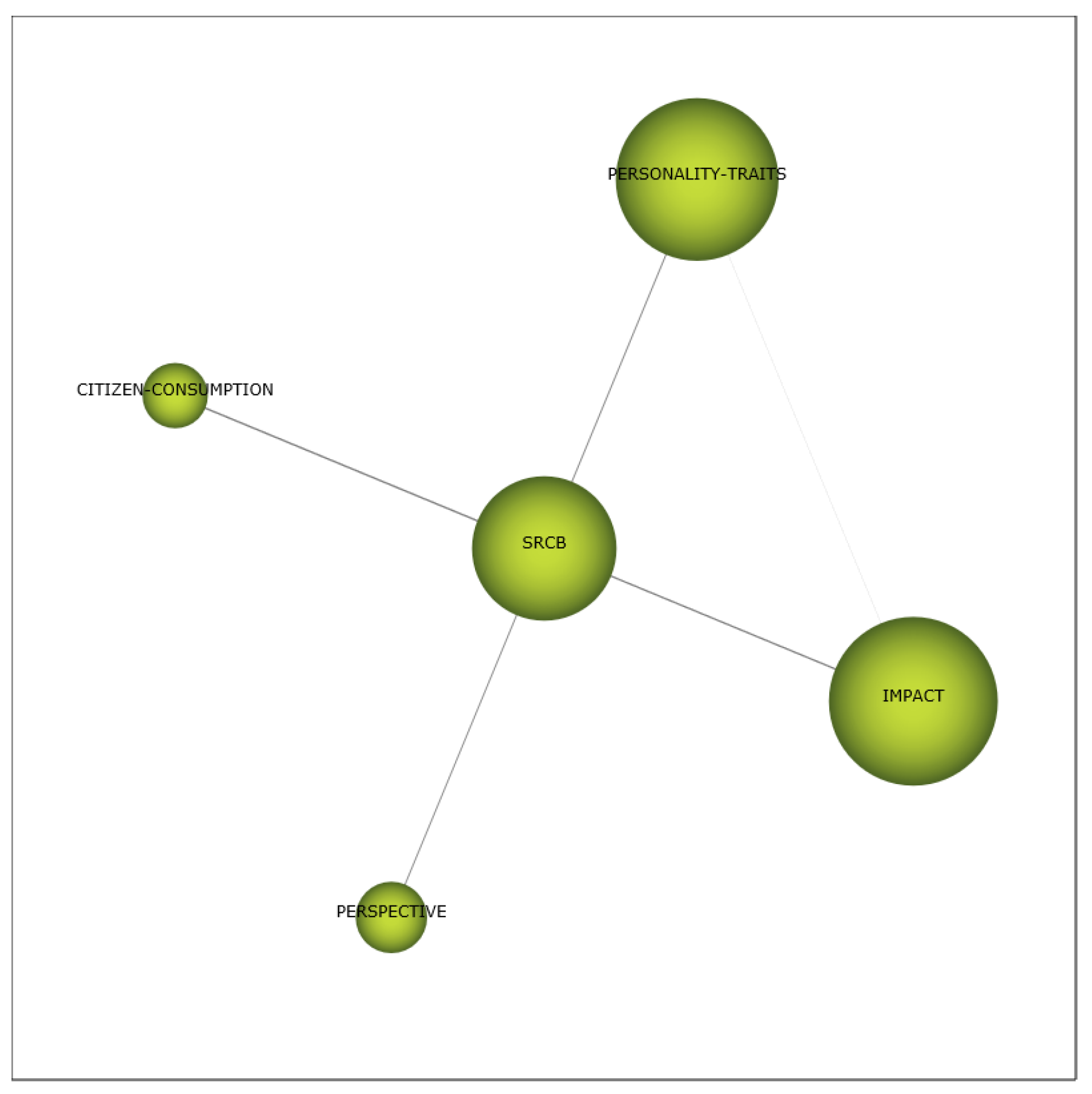

- Research on social and sustainable consumption behavior. These terms apply to the approach taken by various evolving studies, whose central theme is “socially responsible consumption behavior” or “sustainable consumption behavior”. These highlight different “countries and areas” of application and focus on “consumer decision-making”, with reference, in the last period, to the “methodology” used.

- Research on identity and willingness to pay. This approach, which again covers all three periods, is based on the relationships established between “measurement and scales”, “identity”, and “willingness to pay”.

- Research on ‘Ethos Marketing’. This approach emerged in the first study period with “ethics” and is linked to “marketing and management” and “branding” in the second period. “Ethos” is most important for brand management and brand reputation, since it defines the what and why of the brand. Perhaps its development could be extended into the third period through the link established between “marketing and management” and “green sustainable product”, that is, cohesion with the following (“green” concern) approach.

- Research on ‘green’ concern. “Green” concern is an approach that emerged in the second period, related to the cluster “clothing, shoes, and fashion” and, thereafter, with the third period clusters “green sustainable product” and “green”, from 2012 to the present.

- Established theory-based approaches. Finally, this approach was developed from articles that, in the last two periods, presented a solid theoretical framework (“other theories”) about the “consumer”.

5. Discussion of Results

“Has academic research been more focused on CSR and sustainability than on the role of consumers and their socially responsible behavior?”(RQ1)

“To what extent is SRCB a developed or fragmented theme in the academic literature?”(RQ2)

“What other themes are linked to SRCB research?”(RQ3)

“How have these themes evolved since 1991?”(RQ4)

“What are the most important themes and subject areas in terms of academic output?”(RQ5)

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author | Papers | Percentage | Average Year a | Average Citations b | AWCR c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaw, Deirdre (Univ. of Glasgow, Scotland) | 9 | 2.65% | 2009 | 62.33 | 5.29 |

| Papaoikonomou, Eleni (Univ. Rovira & Virgili, Spain) | 7 | 2.06% | 2014 | 18.14 | 2.37 |

| Arli, Denni I. (Griffith Univ., Australia) | 5 | 1.47% | 2016 | 15.00 | 2.55 |

| Manyukhina, Yana (Univ. Leeds, England) | 5 | 1.47% | 2018 | 0.40 | 0.13 |

| Carrington, Michal Jemma (Univ. Melbourne, Australia) | 4 | 1.18% | 2014 | 126.00 | 16.18 |

| McEachern, Morven G. (Univ. Huddersfield, England.) | 4 | 1.18% | 2011 | 21.50 | 1.60 |

| Neville, Benjamin A. (Univ. Melbourne, Australia) | 4 | 1.18% | 2014 | 126.00 | 16.18 |

| Newholm, Terry (Univ. Manchester, England) | 4 | 1.18% | 2010 | 102.00 | 8.43 |

| Vitell, Scott J. (Univ. Mississippi, MS, USA.) | 4 | 1.18% | 2018 | 19.25 | 5.13 |

| Chatzidakis, Andreas (Royal Holloway Univ. London, England.) | 4 | 1.18% | 2011 | 48.75 | 4.44 |

| Ryan, Gerard (Univ. Rovira & Virgili, Spain) | 4 | 1.18% | 2013 | 27.75 | 3.44 |

| Total | 340 d | 100.00 | 2013 | 49.07e | 5.54e |

| Authors | Title | Journal | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maignan [27] | Consumers’ perceptions of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison | J. Bus. Ethic | 375 |

| Carrington, Neville and Whitwell [84] | Why Ethical Consumers Don’t Walk Their Talk: Towards a Framework for Understanding the Gap Between the Ethical Purchase Intentions and Actual Buying Behaviour of Ethically Minded Consumers | J. Bus. Ethic | 336 |

| Auger and Devinney [35] | Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions | J. Bus. Ethic | 225 |

| Johnston [17] | The citizen-consumer hybrid: ideological tensions and the case of Whole Foods Market | Theory Soc. | 219 |

| Shaw and Newholm [33] | Voluntary simplicity and the ethics of consumption | Psychol. Mark. | 203 |

| Bagnoli and Watts [41] | Selling to socially-responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods | J. Econ. Manag. Strategy | 196 |

| Webb, Mohr and Harris [47] | A re-examination of socially-responsible consumption and its measurement | J. Bus. Res. | 165 |

| Shaw, Newholm and Dickinson [34] | Consumption as voting: an exploration of consumer empowerment | Eur. J. Mark. | 160 |

| Clarke, Barnett, Cloke and Malpass [37] | Globalising the consumer: Doing politics in an ethical register | Political Geogr. | 142 |

| Chatzidakis, Hibbert and Smith [45] | Why people don’t take their concerns about fair trade to the supermarket: The role of neutralisation | J. Bus. Ethic | 140 |

| Journal | Documents |

|---|---|

| Journal of Business Ethics | 40 |

| International Journal of Consumer Studies | 15 |

| Sustainability | 8 |

| Social Responsibility Journal | 7 |

| European Journal of Marketing | 6 |

| Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics | 6 |

| Journal of Marketing Management | 6 |

| Journal of Business Research | 5 |

| Journal of Consumer Culture | 5 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 5 |

| Thematic Area | Documents |

|---|---|

| Research on CSR | 243 |

| Research on attitude | 238 |

| Research on social and sustainable consumption behavior | 202 |

| Research on ‘Ethos Marketing’ | 93 |

| Established theory-based approaches | 79 |

| Research on sociocultural factors under the auspices of environmental orientation | 73 |

| Research on identity and willingness to pay | 66 |

| Research on ‘green’ concern | 54 |

| Words | Documents |

|---|---|

| Consumption | 83 |

| Ethical consumer | 82 |

| Behavior | 79 |

| Attitude | 71 |

| CSR | 69 |

| Fair trade | 68 |

| Ethics | 59 |

| Consumer | 57 |

| Consumer behavior | 57 |

| Country & areas | 49 |

References

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Van Tulder, R. International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobeiri, S.; Rajaobelina, L.; Durif, F.; Boivin, C. Experiential Motivations of Socially Responsible Consumption. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 58, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, L.E.V.; Perdomo-Ortiz, J.; Ocampo, S.D.; León, W.F.D. Socially responsible consumption: An application in Colombia. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D.; Böhme, T.; Geiger, S.M. Measuring young consumers’ sustainable consumption behavior: Development and validation of the YCSCB scale. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Shaw, D. Sustainability: Issues of Scale, Care and Consumption. Br. J. Manag. 2018, 29, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höchstädter, A.K.; Scheck, B. What’s in a Name: An Analysis of Impact Investing Understandings by Academics and Practitioners. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 132, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-González, M.M.; Chamorro-Mera, A. Analysis of the predictive variables of the intention to invest in a socially responsible manner. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszewska, M. A typology of Polish consumers and their behaviours in the market for sustainable textiles and clothing. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Young, J.A. What determines British consumers’ motivation to buy sustainable seafood? Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1289–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Organic food as self-presentation: The role of psychological motivation in older consumers’ purchase intention of organic food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain: Lessons from H&M. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6236–6249. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos, E.S.; Cioca, L.-I.; Dan, V.; Ciomos, A.O.; Crisan, O.A.; Barsan, G. Studies and Investigation about the Attitude towards Sustainable Production, Consumption and Waste Generation in Line with Circular Economy in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.; Dulsrud, A. Will Consumers Save The World? The Framing of Political Consumerism. J. Agric. Environ. Ethic. 2007, 20, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J. The citizen-consumer hybrid: Ideological tensions and the case of Whole Foods Market. Theory Soc. 2008, 37, 229–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parigi, P.; Gong, R. From grassroots to digital ties: A case study of a political consumerism movement. J. Consum. Cult. 2014, 14, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, G.M.; Belk, R.; Devinney, T.M. Why don’t consumers consume ethically? J. Consum. Behav. 2010, 9, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A. Strengths and weaknesses of common sustainability indices for multidimensional systems. Environ. Int. 2008, 34, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitell, S.J. A Case for Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR): Including a Selected Review of Consumer Ethics/Social Responsibility Research. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 130, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An approach for detecting, quantifying, and visualizing the evolution of a research field: A practical application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory field. J. Inf. 2011, 5, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F.; López-Herrera, A. SciMAT: A new science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 1609–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, W.T.; Cunningham, W.H. The Socially Conscious Consumer. J. Mark. 1972, 36, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Consumer behavior: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I. Consumers’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibilities: A Cross-Cultural Comparison. J. Bus. Ethic 2001, 30, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; Meulenberg, M.T.; Van Trijp, H.C. Buyer social responsibility: A general concept and its implications for marketing management. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 1428–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.R.; Hewege, C.R. Elderly consumers’ sensitivity to corporate social performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 786–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibiiity: Toward the Moral Management of Organizational Stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Newholm, T. Voluntary simplicity and the ethics of consumption. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Newholm, T.; Dickinson, R. Consumption as voting: An exploration of consumer empowerment. Eur. J. Mark. 2006, 40, 1049–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; DeVinney, T.M. Do What Consumers Say Matter? The Misalignment of Preferences with Unconstrained Ethical Intentions. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.M.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G.; Birtchnell, T. The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility. SSRN Electron. J. 2006, 30, 30–37, Leeds University Business School Working Paper No. 15-04. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.901863 (accessed on 10 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Barnett, C.; Cloke, P.; Malpass, A. Globalising the consumer: Doing politics in an ethical register. Political Geogr. 2007, 26, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucic, T.; Harris, J.; Arli, D. Ethical Consumers Among the Millennials: A Cross-National Study. J. Bus. Ethic 2012, 110, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E. El Consumidor Verde: Bases de un Modelo de Comportamiento. ESIC Mark. 1997, 96, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli, M.; Watts, S.G. Selling to socially responsible consumers: Competition and the private provision of public goods. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2003, 12, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniero, G.; Codini, A.; Bonera, M.; Corvi, E.; Bertoli, G. Being green: From attitude to actual consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory-Smith, D.; Manika, D.; Demirel, P. Green intentions under the blue flag: Exploring differences in EU consumers’ willingness to pay more for environmentally-friendly products. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Shaw, D. Identifying fair trade in consumption choice. J. Strat. Mark. 2006, 14, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidakis, A.; Hibbert, S.; Smith, A.P. Why People Don’t Take their Concerns about Fair Trade to the Supermarket: The Role of Neutralisation. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C.; Burke, C.; Talbott, E.; Green, G.P. ‘Taste Great or More Fulfilling’: The Effect of Brand Reputation on Consumer Social Responsibility Advertising for Fair Trade Coffee. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of eco-conscious apparel acquisition behaviors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, M.; Kilburn, A.; Miles, M.P. The effect of purchase situation on realized pro-environmental consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, H.-J.; Nelson, M.R. To Buy or Not to Buy: Determinants of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior and Consumer Reactions to Cause-Related and Boycotting Ads. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2009, 31, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.C. Understanding ethical consumers: Willingness-to-pay by moral cause. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, F.E., Jr. Determining the Characteristics of the Socially Conscious Consumer. J. Consum. Res. 1975, 2, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quazi, A.; Amran, A.; Nejati, M. Conceptualizing and measuring consumer social responsibility: A neglected aspect of consumer research. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 40, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E.; Hodges, N.N. Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior? Exploring Used Clothing Donation Behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2009, 27, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berné-Manero, C.; Pedraja-Iglesias, M.; Ramo-Sáez, P. A measurement model for the socially responsible consumer. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2013, 11, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, A.; Rajah, E.; Gaur, S.S. Consumers’ beliefs about firm’s CSR initiatives and their purchase behavior. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 34, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Chatzidakis, A. Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR): Toward a Multi-Level, Multi-Agent Conceptualization of the “Other CSR. ” J. Bus. Ethic 2013, 121, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.T.; Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. The Ethical Consumer; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Glänzel, W. Bibliometrics-aided retrieval: Where information retrieval meets scientometrics. Scientometrics 2014, 102, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; McMaster, R.; Newholm, T. Care and Commitment in Ethical Consumption: An Exploration of the ‘Attitude–Behaviour Gap’. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 136, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Shiu, E. Ethics in consumer choice: A multivariate modelling approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Ryan, G.; Ginieis, M. Towards a Holistic Approach of the Attitude Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumer Behaviours: Empirical Evidence from Spain. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 2010, 17, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G. Lost in translation: Exploring the ethical consumer intention–behavior gap. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacout, O.M.; Vitell, S.J. Ethical consumer decision-making: The role of need for cognition and affective responses. Bus. Ethic A Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjiptono, F.; Arli, D.; Winit, W. Gender and young consumer ethics: An examination in two Southeast Asian countries. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Salustri, F. The Vote with the Wallet Game: Responsible Consumerism as a Multiplayer Prisoner’s Dilemma. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Latour, M.S. The Link between Social Responsibility Orientation, Motive Appeals, and Voting Intention: A Case of an Anti-littering Campaign. J. Public Policy Mark. 1991, 10, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groos, O.V.; Pritchard, A. Documentation notes. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culnan, M. The intellectual development of management information systems. Manag. Sci. 1986, 32, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J.; Martínez-Fiestas, M. Detecting salient themes in financial marketing research from 1961 to 2010. Ser. Ind. J. 2013, 33, 925–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Porcu, L.; Del Barrio-García, S. Discovering prominent themes of integrated marketing communication research from 1991 to 2012: A co-word analytic approach. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 678–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, M.E.; Alcántara-Pilar, J.M.; Del Barrio-García, S.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. A review of restaurant research in the last two decades: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, A.; Salo, J. A bibliometric analysis of extended key account management list. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.; Penan, H. Cienciometría. El estudio cuantitativo de la actividad científica: de la bibliometría a la vigilancia tecnológica; Ediciones TREA: Gijón, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garfield, E. Current comments. Keywords plus-ISIS breakthrough retrieval method. 1. Expanding your searching power on current-contents on diskette. Curr. Contents 1990, 32, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, M.J. SciMAT: Herramienta Software Para El Análisis De La Evolución Del Conocimiento Científico. Propuesta De Una Metodología De Evaluación. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, M.; Cui, L. Integration of three visualization methods based on co-word analysis. Scientometrics 2011, 90, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: The case of polymer chemistry. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 155–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, R.P.; Robinson, L.M.; Bragge, J.; Somervuori, O. A citation and profiling analysis of pricing research from 1980 to 2010. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1010–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchakoui, S.; Mathieu, A. Marketing trends: Content analysis of the major journals (2001-2006). In Proceedings of the Administrative Sciences Association of Canada, Nova Scotia, NS, Canada, 27–28 May 2008; pp. 114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.H.; Liang, L.M.; Rousseau, R.; Egghe, L. The AR-index: Complementing the h-index. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G. Why Ethical Consumers Don’t Walk Their Talk: Towards a Framework for Understanding the Gap Between the Ethical Purchase Intentions and Actual Buying Behaviour of Ethically Minded Consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M.; Ruiz, F.J.T.; Cobo, M.J. Analysing the conceptual evolution of qualitative marketing research through science mapping analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 102, 519–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczniak, G.R.; Murphy, P.E. Ethical Marketing Decisions: The Higher Road; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Grauers, A.; Sarasini, S.; Karlstrom, M. Why Electromobility and What Is It? In Systems Perspectives on Electromivility; Sandén, B., Wallgren, P., Eds.; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburyg, Sweden, 2013; pp. 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—WHO. WHO Releases Country Estimates on Air Pollution Exposure and Health Impact; WHO: Geneva, Swizerland, 2016; pp. 1–2. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/27-09-2016-who-releases-country-estimates-on-air-pollution-exposure-and-health-impact (accessed on 10 October 2019).

| 1 | Shaw, Deirdre (Univ. of Glasgow, Scotland) |

| Period | Theme/Concept | Documents | Citations | h-Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991–2012 | Ethics | 19 | 1076 | 16 |

| Fair trade | 15 | 1234 | 13 | |

| Country areas | 10 | 370 | 9 | |

| Attitude | 8 | 766 | 7 | |

| Behavior | 7 | 339 | 6 | |

| Socially responsible consumption behavior | 7 | 311 | 5 | |

| Measurement scales | 6 | 485 | 4 | |

| Sustainable consumption behavior | 4 | 135 | 3 | |

| Economy | 3 | 259 | 3 | |

| Environmental orientation | 3 | 170 | 2 | |

| Productivity | 2 | 209 | 2 | |

| Social media | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2013–2016 | Attitude | 28 | 579 | 13 |

| CSR | 28 | 456 | 12 | |

| Consumption | 11 | 369 | 8 | |

| Sociocultural factors | 11 | 131 | 5 | |

| Branding | 10 | 110 | 7 | |

| Consumer decision-making | 10 | 146 | 7 | |

| Consumer care | 9 | 259 | 6 | |

| Identity | 9 | 126 | 7 | |

| Models | 8 | 93 | 5 | |

| Country areas | 7 | 74 | 5 | |

| Measurement scales | 7 | 81 | 5 | |

| Clothing and shoes fashion | 5 | 90 | 3 | |

| Theory of Planned Behavior | 4 | 52 | 4 | |

| Marketing & Management | 2 | 7 | 1 | |

| Other theories | 2 | 12 | 2 | |

| Preference | 2 | 13 | 1 | |

| 2017–2019 | Ethical consumer | 23 | 53 | 5 |

| Organic products | 20 | 62 | 3 | |

| Sociocultural factors | 20 | 45 | 4 | |

| Knowledge & Information | 15 | 19 | 3 | |

| Ethical consumption | 14 | 21 | 3 | |

| Consumer | 13 | 43 | 4 | |

| Methodology | 12 | 30 | 3 | |

| SRCB | 12 | 26 | 3 | |

| Multivariate data analysis | 10 | 33 | 3 | |

| Intention | 8 | 42 | 3 | |

| Willingness to pay | 7 | 18 | 2 | |

| Business | 6 | 8 | 2 | |

| Green | 6 | 10 | 2 | |

| Sustainability | 6 | 2 | 8 | |

| Green sustainable product | 5 | 39 | 3 | |

| Cause-related marketing | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Choice | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Public good | 2 | 1 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nova-Reyes, A.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Luque-Martínez, T. The Tipping Point in the Status of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Research? A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083141

Nova-Reyes A, Muñoz-Leiva F, Luque-Martínez T. The Tipping Point in the Status of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Research? A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083141

Chicago/Turabian StyleNova-Reyes, Andrés, Francisco Muñoz-Leiva, and Teodoro Luque-Martínez. 2020. "The Tipping Point in the Status of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Research? A Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083141

APA StyleNova-Reyes, A., Muñoz-Leiva, F., & Luque-Martínez, T. (2020). The Tipping Point in the Status of Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior Research? A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 12(8), 3141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083141