The Sustainable Positive Effects of Enterprise Social Media on Employees: The Visibility and Vicarious Learning Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. ESM Visibility

2.1.1. The Four Categories of Visibility

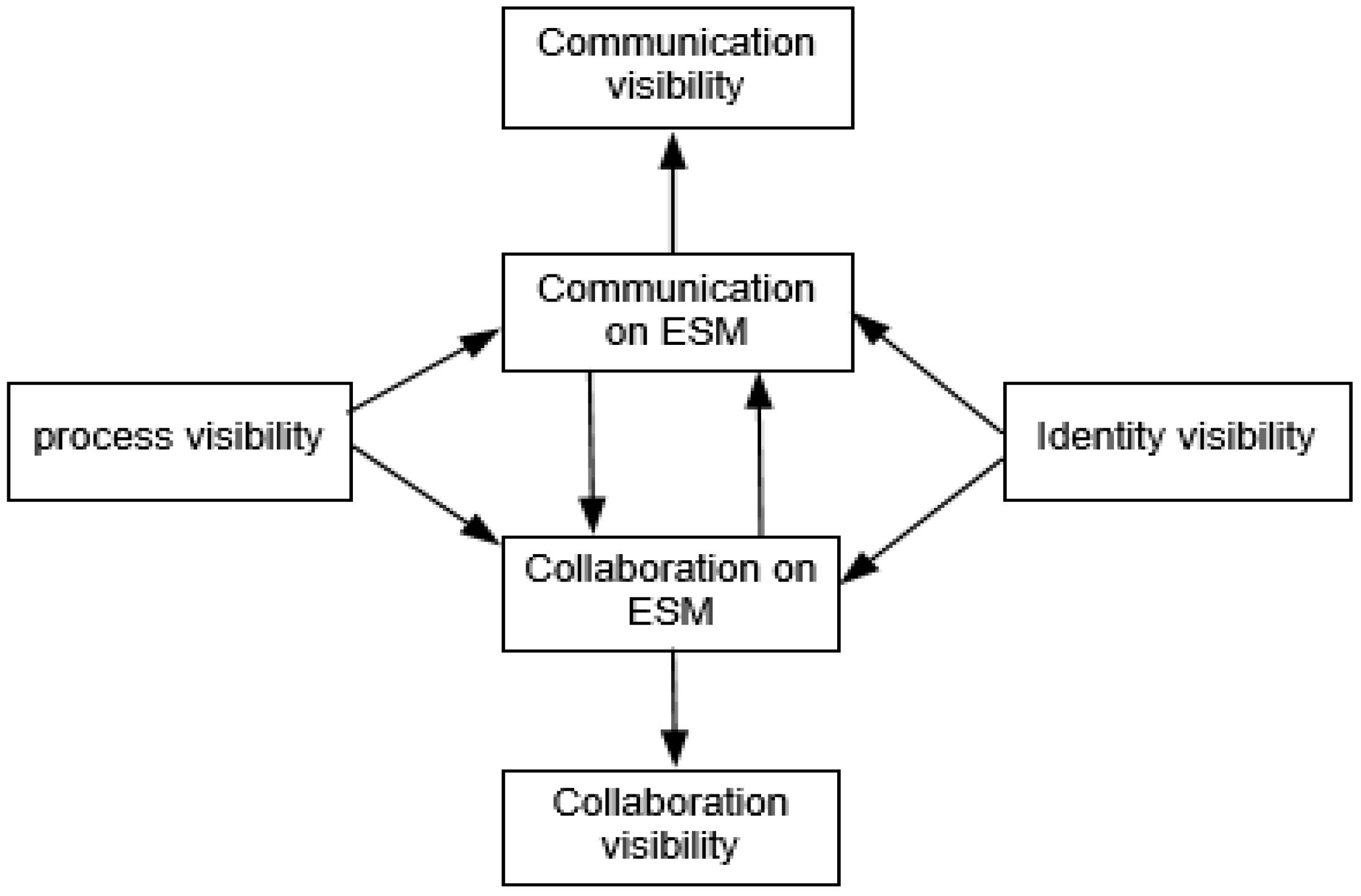

2.1.2. The Relationships of Four Categories of Visibility

2.2. Vicarious Learning

2.2.1. Review of Vicarious Learning

2.2.2. Vicarious Learning in the Context of ESM

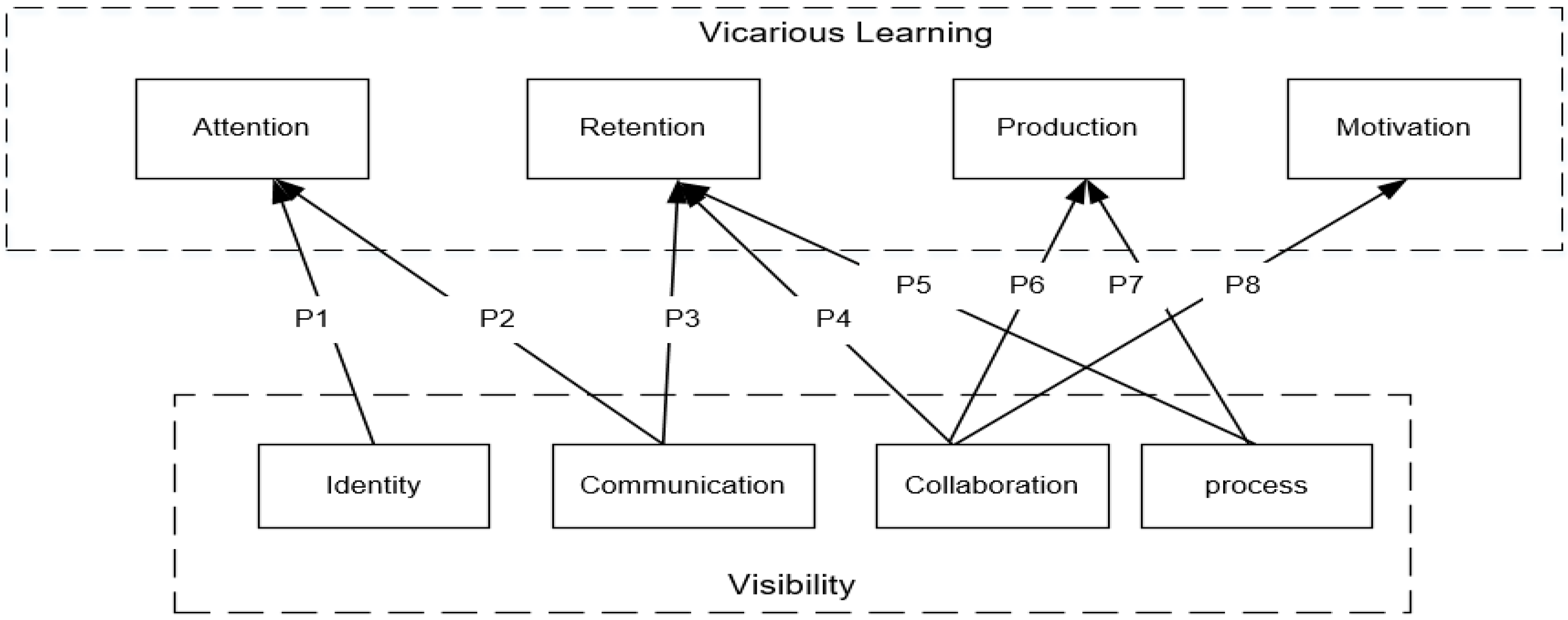

3. Theoretical Propositions

3.1. The Relationship between Identity Visibility and Attention Process

3.2. The Relationship between Communication Visibility and the Attention Process

3.3. The Relationship between Communication Visibility and the Retention Process

3.4. The Relationship between Collaboration Visibility and the Retention Process

3.5. The Relationship between Process Visibility and the Retention Process

3.6. The Relationship between Collaboration Visibility and the Production Process

3.7. The Relationship between Process Visibility and the Production Process

3.8. The Relationship between Collaboration Visibility and the Motivation Process

4. Research Methods

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis

- Raw data: “I have some groups of projects, all the project-related matters, decision-making arrangements, meeting notices are published in the group. I can also see everyone talking about the implementation of the project in this group, because our manager asked us to give feedback to questions in this group”.

- Code: visible information, collaboration between group members

- Subtheme: project discussion of information visibility

- Theme: collaboration visibility

5. Case Analysis

5.1. P1: Identity Visibility Promotes the User’s Attention Process

5.2. P2: Communication Visibility Promotes the User’s Attention Process

5.3. P3: Communication Visibility Promotes the User’s Retention Process

5.4. P4: Collaboration Visibility Promotes the User’s Retention Process

5.5. P5: Process Visibility Promotes Users’ Retention Process

5.6. P6: Collaboration Visibility Promotes the User’s Production Process

5.7. P7: Process Visibility Promotes the User’s Production Process

5.8. P8: Collaboration Visibility Promotes the User’s Motivation Process

5.9. Summary of Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Implications

6.1.1. Theoretical Implications

6.1.2. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Could you introduce yourself first? And tell us the main content of your job.

- Could you talk about how you use DingTalk at work? What features do you use frequently?

- How do you feel that using DingTalk will help you?

- Do you actively look for information on DingTalk? And what kind of information can you see or find on DingTalk?

- Do you feel that your colleagues use DingTalk frequently? What content or information do other colleagues post on DingTalk?

- Do you feel that using DingTalk will help improve your learning ability? If so, how is it realized? Could you give a concrete example to illustrate?

- Does enterprise use DingTalk to promote employee training or experience sharing? What do you think is the role of DingTalk in this process?

- Do you think the use of DingTalk can help you discover the knowledge you need faster? If so, how did you find it on DingTalk?

- What kind of information on DingTalk is helpful for improving or facilitating your learning ability?

- How did you find others on DingTalk? Do you spend time browsing other people’s profile pages? How you think this information will help you?

- Will managers praise top performers on DingTalk? Does it promote your desire to learn from them?

- Could you show us how you used DingTalk on your mobile phone?

- What help does DingTalk offer in terms of collaboration between you and your colleagues?

- What do you think of the process management on the DingTalk? And what impact does it have on you?

- Do you think that communication among colleagues will promote your own learning effect? And what do your colleagues usually do to help you on DingTalk?

- Can you successfully master the knowledge shared by others, and if you have any questions, how will you solve them?

Appendix B

| No. | Interviewees | Enterprise | Interview Date | Interview Time (Minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ye, Cai | D | 2018.1 | 118 |

| 2 | Zhu | D | 2018.1 | 77 |

| 3 | Wang | D | 2018.1 | 21 |

| 4 | Zhu | D | 2018.3 | 32 |

| 5 | Lu | D | 2018.3 | 43 |

| 6 | Ding | D | 2018.3 | 22 |

| 7 | Xu | D | 2018.3 | 41 |

| 8 | He, Luo | F | 2018.6 | 11 |

| 9 | He | F | 2018.6 | 86 |

| 10 | Luo | F | 2018.6 | 4 |

| 11 | Jin | F | 2018.6 | 123 |

| 12 | He | F | 2018.6 | 7 |

| 13 | Li | F | 2018.6 | 57 |

| 14 | Wen, Yao | F | 2018.6 | 46 |

| 15 | He | F | 2019.1 | 15 |

| 16 | He, Luo | F | 2019.1 | 108 |

| 17 | He, Luo | F | 2019.1 | 33 |

| 18 | Cheng | F | 2019.1 | 86 |

| 19 | Luo | F | 2019.1 | 77 |

| 20 | Luo | F | 2019.1 | 64 |

| 21 | Song, Luo | F | 2019.1 | 23 |

| 22 | Wu | F | 2019.1 | 90 |

| 23 | Luo | F | 2019.1 | 55 |

| 24 | Ding | F | 2019.1 | 70 |

| 25 | He | F | 2019.1 | 53 |

| Total | 1362 | |||

Appendix C

| No. | Interviewees | Enterprise | Job | Interview Word Counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ye, Cai | D | Department of Legal Compliance Assistant, Director of Personnel Administration | 30,105 |

| 2 | Zhu | D | Director of Personnel Administration | 23,969 |

| 3 | Wang | D | Operations Management Division Operations Specialist | 6210 |

| 4 | Zhu | D | Personnel Administration Commissioner | 11,279 |

| 5 | Lu | D | Business manager | 10,605 |

| 6 | Ding | D | Personnel Administration Commissioner | 5629 |

| 7 | Xu | D | Collaborative Development Staff | 10,365 |

| 8 | He, Luo | F | Vice president of information, Deputy Manager of Software Development | 1748 |

| 9 | He | F | Vice president of information, | 15,155 |

| 10 | Luo | F | Deputy Manager of Software Development | 787 |

| 11 | Jin | F | Executive Vice President | 32,696 |

| 12 | He | F | Vice president of information | 1006 |

| 13 | Li | F | Senior engineer | 16,097 |

| 14 | Wen, Yao | F | Operations Management Manager, production manager | 13,031 |

| 15 | He | F | Vice president of information | 3050 |

| 16 | He, Luo | F | Vice president of information, Deputy Manager of Software Development | 26,013 |

| 17 | He, Luo | F | Vice president of information, Deputy Manager of Software Development | 6717 |

| 18 | Cheng | F | Product manager | 22,256 |

| 19 | Luo | F | Deputy Manager of Software Development | 20,434 |

| 20 | Luo | F | Deputy Manager of Software Development | 18,014 |

| 21 | Song, Luo | F | Supplier, Deputy Manager of Software Development | 5630 |

| 22 | Wu | F | Deputy General Manager of Cloud Development Department | 25,217 |

| 23 | Luo | F | Director of Marketing Management | 14,094 |

| 24 | Ding | F | Product manager | 16,287 |

| 25 | He | F | Vice president of information | 11,490 |

| Total | 348,424 | |||

Appendix D

| Propositions | Sample Excerpts Supporting Each Proposition |

|---|---|

| 1 | “There exists the personal information of different colleagues on DingTalk, I can contact my colleague in the first time. We should all be in the same company, so he can find me on DingTalk. He must be my colleagues, and I can be sure of his identity. I can chat directly with him without adding friend. There are some questions about information he or she shared on DingTalk that can be answered directly, unlike chatting via WeChat which I need to confirm my identity by adding a friend first.” “The information of the positions in each department for every colleague can be seen on DingTalk. It’s better to know what departments our company has, and it’s more convenient to connect, we can directly connect to everyone in the company to ask for help.” “It is also convenient to find some experts in our company, you can find them at any time, no need to go through the address book to find this person, it will be more convenient. Don’t need to spend time looking for this person.” |

| 2 | “Occasionally I see what can help us in our work, such as about the technical aspects and some new improvements. Basically, if this knowledge is closely related to us, I will post it on DingTalk. Our manager (He) also always share some experiences.” “When I have some knowledge that may be useful to many people, I will share it on DingTalk directly, publish it in group on DingTalk so that the people who need it can see it. It is a one-to-many sharing.” “If there is a person who has published a lot of knowledge on DingTalk and it is also closely related to what we need, then we will look for him next time if we meet some difficulties, or if we have a meeting, we will invite him to attend our meeting.” |

| 3 | “This means that others get my intention, because the most important thing between colleagues is that I can understand what you said, and you know if I understand. This is the most important. I feel that I have a common topic with him, or that everyone can share goals and communication together. when I share some experiences and knowledge, if other colleagues click the button of ‘I like’ under this information, I will feel that it is a kind of consensus that others understand the meaning of my knowledge.” “Some technical department staff will answer more professionally, or I can’t understand it, or if the problem is more technical, I will let them go my office offline to help me solve the problem.” “If you know your colleague better, like an old saying in China, ‘All is understood, and no words are necessary,’ and you will quickly understand what he wants to express.” |

| 4 | “For example, Zhang San’s performance this month is particularly good, we will let him share his experience, for example, how do you do it. He may share, for example, what method he uses, he will share in the group. Then others will discuss it to better understand it because this knowledge or experience may be only suitable for him.” “Maybe you don’t understand what he said, but it’s okay, because we will all discuss about it. Maybe other people who understand have changed the way of expression, maybe you can understand it better, and this situation is quite common.” |

| 5 | “For example, if he will go on a business trip, he needs to go through the process of approval for reimbursement for buying tickets. If he goes through this process, then his chat box will present his activity status, showing during this time he is at business trips. Or if he goes out this afternoon, this information also will be displayed.” “If he is in a meeting and I see this information, then I will not ask for his help or wait his reply and I will ask others for solving my confusions, which improves my experience and comprehend knowledge more comfortably.” “I submit many approvals, for example, a leader may at business trip or meeting, the approval will be faster on DingTalk, so that it can be submitted to the court in time or docked with the bank.” “Manager (He) always shared what he saw about new architecture, and the architecture which is very important for us. The latest product design is related to the work we usually do. This knowledge is very suitable for us and we will definitely understand what it means and then absorb it.” |

| 6 | “The knowledge documents related to our work, knowledge about our project, is equivalent to the data, regardless of the research data, the knowledge materials of everyone, and the reference materials, all posts share and sort it, we can see them.” “I have joined several groups, including groups of recruiting classes, or groups with some other classes, which often released video at some point of time. Then I will go check this content.” “We have a person in our technical department who sorts out the problems and solutions that everyone feedbacks, publishes it in the group, and then updates it every so often until the system runs successfully in the enterprise. This both reduce the burden on technicians and speed up problem resolution.” |

| 7 | “In the past, his approval was made by telephone, the call was made to the buyer, and the buyer called to the warehouse. But now it is how much the supplier were copied, and whether it was in or not in the plan. Buyer can see the entire data. There is no need for any communication, and the result is the buyer’s approval, the warehouse management can see it at the same time. They just don’t need to contact by the phone, realizing real-time collaboration”. “That is to say, you will think differently. If you know your colleague’s work, you can better understand what he means. Combined with your own specific work situation, you can use these experiences more flexibly.” |

| 8 | “It’s basically a lot of text communication on DingTalk, you can see what others shared and find it in previous communication, and the documents can be shared, and the people who enter the group later can see the files shared previously.” “This kind of brainstorming is very helpful. The more people shared his experience on how to apply it and the outcomes, the more confidence you will have. Because many people have succeeded in applying this knowledge in their work, you will believe that ‘I can also do that.’ In this situation, some of the difficulties you encounter later will not hinder your confidence in continuing to use this knowledge.” |

Appendix E

| Research Design | |

| Clear research question | Yes, ‘how’ |

| Multiple-case design | Yes, two |

| Replication logic in multiple-case design | literal |

| Unit of analysis | Employees using DingTalk |

| Use of a pilot case | Not conducted as it is recommended for highly exploratory nature |

| Team-based research | Yes |

| Different roles for multiple investigators | Yes |

| Data collection | |

| Elucidation of the data collection process | Yes |

| Multiple data collection methods | Yes |

| Data triangulation | Yes |

| Case study database | Yes |

| Data analysis | |

| Elucidation of the data analysis process | Yes |

| Field notes | Yes |

| Coding and reliability check | There were several ways, as we describe in Section 4. First, the accuracy of one’s compiled transcripts was verified by another member; second, we had several meetings to discuss the interpretations; third, we have the database [105]. |

| Data displays | Yes |

| Logical chain of evidence | Yes, our research question led to the propositions. Then these propositions guided data collection and analysis that provide the final evidence. |

| Quotes (evidence) | Yes |

References

- Zuchowski, O.; Posegga, O.; Schlagwein, D.; Fischbach, K. Internal Crowdsourcing: Conceptual Framework, Structured Review, and Research Agenda. J. Inf. Technol. 2016, 31, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, Z. How Newcomers’ Work-Related Use of Enterprise Social Media Affects Their Thriving at Work—The Swift Guanxi Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M.; Vaast, E. Social Media and Their Affordances for Organizing: A Review and Agenda for Research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 150–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J. Effects of the Use of Social Network Sites on Task Performance: Toward a Sustainable Performance in a Distracting Work Environment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A. Enterprise 2.0: The dawn of emergent collaboration. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pee, L. Affordances for sharing domain-specific and complex knowledge on enterprise social media. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostervink, N.; Agterberg, L.; Huysman, M. Knowledge Sharing on Enterprise Social Media: Practices to Cope with Institutional Complexity. J. Comput. Commun. 2016, 21, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Bostrom, R. Technology-Mediated Learning: A Comprehensive Theoretical Model. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresman, H. Changing Routines: A Process Model of Vicarious Group Learning in Pharmaceutical R&D. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, C.G. Coactive Vicarious Learning: Toward a Relational Theory of Vicarious Learning in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledow, R.; Carette, B.; Kühnel, J.; Bister, D.; Pittig, D. Learning from Others’ Failures: The Effectiveness of Failure Stories for Managerial Learning. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 16, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, D.; Staats, B.R.; Gino, F. Learning from My Success and from Others’ Failure: Evidence from Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 2435–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woudstra, L.; Hooff, B.V.D.; Schouten, A. Dimensions of quality and accessibility: Selection of human information sources from a social capital perspective. Inf. Process. Manag. 2012, 48, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Osch, W.; Steinfield, C. Team Boundary Spanning: Strategic Implications for the Implementation and use of Enterprise Social Media. J. Inf. Technol. 2016, 31, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C. Enterprise Social Media: Current Capabilities and Future Possibilities. MIS Q. Exec. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi, P.M.; Huysman, M.; Steinfield, C. Enterprise Social Media: Definition, History, and Prospects for the Study of Social Technologies in Organizations. J. Comput. Commun. 2013, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Social Media, Knowledge Sharing, and Innovation: Toward a Theory of Communication Visibility. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 796–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treem, J.W.; Leonardi, P.M. Social Media Use in Organizations: Exploring the Affordances of Visibility, Editability, Persistence, and Association. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2013, 36, 143–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortoriello, M. The social underpinnings of absorptive capacity: The moderating effects of structural holes on innovation generation based on external knowledge. Strat. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Osch, W.; Steinfield, C.W. Strategic Visibility in Enterprise Social Media: Implications for Network Formation and Boundary Spanning. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 647–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-Y.; Gong, Y.; Peng, M.W. Expatriate Knowledge Transfer, Subsidiary Absorptive Capacity, and Subsidiary Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 927–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Murtic, A.; Zander, U.; Richtnér, A. What Fosters Individual-Level Absorptive Capacity in MNCs? An Extended Motivation–Ability–Opportunity Framework. Manag. Int. Rev. 2018, 59, 93–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network Structure and Knowledge Transfer: The Effects of Cohesion and Range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, B.S.; Harzing, A.-W.; Kraimer, M.L. The role of international assignees’ social capital in creating inter-unit intellectual capital: A cross-level model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 40, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagwein, D.; Conboy, K.; Feller, J.; Leimeister, J.M.; Morgan, L. “Openness” with and without Information Technology: A Framework and a Brief History. J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 32, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Huang, J.-W. Exploitative and exploratory learning in transactive memory systems and project performance. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer-Brown, C.; Kietzmann, J. Strategic knowledge management and enterprise social media. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1288–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D. Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. The social media revolution: Sharing and learning in the age of leaky knowledge. Inf. Organ. 2017, 27, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Alavi, M.; Labianca, G.; Borgatti, S.P. What’s Different about Social Media Networks? A Framework and Research Agenda. MIS Q. Exec. 2014, 38, 274–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, B.; Ritter, C.; Leist, S. Enterprise social networks: A literature review and research agenda. Comput. Netw. 2017, 114, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Ambient Awareness and Knowledge Acquisition: Using Social Media to Learn “Who Knows What” and “Who Knows Whom”. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.; Gerlach, J.; Benlian, A.; Buxmann, P. How employees gain meta-knowledge using enterprise social networks: A validation and extension of communication visibility theory. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Dennis, A.R. Virtual First Impressions Matter: The Effect of Enterprise Social Networking Sites on Impression Formation in Virtual Teams. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammuto, R.F.; Griffith, T.L.; Majchrzak, A.; Dougherty, D.J.; Faraj, S. Information Technology and the Changing Fabric of Organization. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Majchrzak, A. Enhancing performance of geographically distributed teams through targeted use of information and communication technologies. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.B.; Gibbs, J.L.; Weber, M.S. The Use of Enterprise Social Network Sites for Knowledge Sharing in Distributed Organizations: The Role of Organizational Affordances. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Argote, L. Transactive memory systems 1985–2010: An integrative framework of key dimensions, antecedents, and consequences. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 189–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O.; Ye, C.; Kumar, N. A social capital perspective on meta-knowledge contribution and social computing. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Carley, K.M.; Argote, L. The Contingent Effects of Transactive Memory: When Is It More Beneficial to Know What Others Know? Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMicco, J.; Geyer, W.; Millen, D.; Dugan, C.; Brownholtz, B. People Sensemaking and Relationship Building on an Enterprise Social Network Site. In Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, Big Island, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- DiMicco, J.; Millen, D.R.; Geyer, W.; Dugan, C.; Brownholtz, B.; Muller, M. Motivations for social networking at work. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–12 November 2008; pp. 711–720. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, G.C.; Borgatti, S.P. Centrality—Is Proficiency Alignment and Workgroup Performance. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, P.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M. Performance indicators for collaborative business ecosystems—Literature review and trends. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2017, 116, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyo, P.; Liu, K.; Effah, J. Digital business ecosystem: Literature review and a framework for future research. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.; Afsarmanesh, H. On reference models for collaborative networked organizations. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 2453–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbish, L.; Stuart, C.; Tsay, J.; Herbsleb, J. Social coding in GitHub. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Seattle, WA, USA, 11–15 February 2012; pp. 1277–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird, P.; Dabbish, L.; Kiesler, S. Workflow transparency in a microtask marketplace. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 27–31 October 2012; pp. 281–284. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, J.A.; Slaughter, S.A.; Kraut, R.E.; Herbsleb, J. Team Knowledge and Coordination in Geographically Distributed Software Development. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 135–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y.-K. IT-enabled awareness and self-directed leadership behaviors in virtual teams. Inf. Organ. 2018, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Majchrzak, A. How virtual teams use their virtual workspace to coordinate knowledge. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Salas, E.; Pierce, L.; Kendall, D. Understanding team adaptation: A conceptual analysis and model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1189–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, R.; Sánchez-Manzanares, M.; Gil, F.; Gibson, C. Team Implicit Coordination Processes: A Team Knowledge–Based Approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.R.; Valacich, R.M.F.S. Media, Tasks, and Communication Processes: A Theory of Media Synchronicity. MIS Q. 2008, 32, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ha, T.; Lee, D.; Kim, J.H. Understanding the majority opinion formation process in online environments: An exploratory approach to Facebook. Inf. Process. Manag. 2018, 54, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M.; Treem, J.W.; Jackson, M.H. The Connectivity Paradox: Using Technology to Both Decrease and Increase Perceptions of Distance in Distributed Work Arrangements. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2010, 38, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Mathieu, J.E. The Dimensions and Antecedents of Team Virtuality. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 700–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlaak, A.; Gong, Y. Vicarious Learning and Inferential Accuracy in Adoption Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 846–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecassis-Moedas, C.; Sguera, F.; Ettlie, J.E. Observe, innovate, succeed: A learning perspective on innovation and the performance of entrepreneurial chefs. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2840–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, Y. Enacting the lean startup methodology. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 812–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Customers’ purchase decision-making process in social commerce: A social learning perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, G.; Reynolds, G.; Field, A.P.; Field, A.P.; Askew, C.; Askew, C. Learning to fear a second-order stimulus following vicarious learning. Cogn. Emot. 2017, 31, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholson, B.; Craig, S.D. Promoting Constructive Activities that Support Vicarious Learning During Computer-Based Instruction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.Y.; Davis, F.D. Developing and Validating an Observational Learning Model of Computer Software Training and Skill Acquisition. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, W.D.; Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Principles of Behavior Modification; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Ashuri, T.; Dvir-Gvirsman, S.; Halperin, R. Watching Me Watching You: How Observational Learning Affects Self-disclosure on Social Network Sites? J. Comput. Commun. 2018, 23, 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D. Vicarious learning: A review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2010, 10, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeadon-Lee, A. Reflective vicarious learning (RVL) as an enhancement for action learning. J. Manag. Dev. 2018, 37, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.D.; Sullins, J.; Witherspoon, A.; Gholson, B. The Deep-Level-Reasoning-Question Effect: The Role of Dialogue and Deep-Level-Reasoning Questions During Vicarious Learning. Cogn. Instr. 2006, 24, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, M.J.; Butterfield, K.D. The Influence of Unethical Peer Behavior on Observers’ Unethical Behavior: A Social Cognitive Perspective. J. Bus. Ethic. 2011, 109, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.; Mckendree, J.; Tobin, R.; Lee, J.; Mayes, T. Vicarious learning from dialogue and discourse—A controlled comparison. Instr. Sci. 1999, 27, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, F.F. Reducing intercultural friction through fiction: Virtual cultural learning. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2003, 27, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1999, 13, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, C.C.; Sims, H.P. Vicarious Learning: The Influence of Modeling on Organizational Behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Kok, S.; Sakellarios, N.; O’Brien, S. Micro enterprises, self-efficacy and knowledge acquisition: Evidence from Greece and Spain. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzum, M. Expertise seeking: A review. Inf. Process. Manag. 2014, 50, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. Multidimensional Constructs in Organizational Behavior Research: An Integrative Analytical Framework. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 144–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.-W.; Heckscher, C. Perspective—Professional Work: The Emergence of Collaborative Community. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H.; Douglass, A. Relational Bureaucracy: Structuring Reciprocal Relationships into Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.; Clarke, A.D.; Klein, H.J. Learning in the Twenty-First-Century Workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Snellman, K. The Knowledge Economy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, D.; Palanski, M.E.; Olabisi, J.; Joinson, A.; Dove, J. Team dynamics in virtual, partially distributed teams: Optimal role fulfillment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Zhao, M.; Calantone, R.J. Adding Interpersonal Learning and Tacit Knowledge to March’s Exploration-Exploitation Model. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.L.; Choi, H.-S. Creativity and Innovation in Organizational Teams; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, H. To Share or not to Share: The Effects of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivations on Knowledge-sharing in Enterprise Social Media Platforms. J. Inf. Technol. 2016, 31, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative Behavior in the Workplace: The Role of Performance and Image Outcome Expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes and Good Ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 2004, 110, 349–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.Z.; Cross, R. The Strength of Weak Ties You Can Trust: The Mediating Role of Trust in Effective Knowledge Transfer. Manag. Sci. 2004, 50, 1477–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbaum, A.; Tushman, M.L. Building bridges: The social structure of interdependent innovation. Strat. Entrep. J. 2007, 1, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagwein, D.; Hu, M.; Schlagwein, M.H.D. How and why Organisations Use Social Media: Five Use Types and their Relation to Absorptive Capacity. J. Inf. Technol. 2017, 32, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Hoeven, C.L.; Stohl, C.; Leonardi, P.; Stohl, M. Assessing Organizational Information Visibility: Development and Validation of the Information Visibility Scale. Commun. Res. 2019, 46, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wei, S. Enterprise social media use and overload: A curvilinear relationship. J. Inf. Technol. 2019, 34, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boh, W.F. Knowledge sharing in communities of practice. ACM SIGMIS Database. 2014, 45, 8–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Eisenberg, J.; Rozaidi, N.A.; Gryaznova, A. The “Megapozitiv” Role of Enterprise Social Media in Enabling Cross-Boundary Communication in a Distributed Russian Organization. Am. Behav. Sci. 2014, 59, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortoriello, M.; Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Bridging the Knowledge Gap: The Influence of Strong Ties, Network Cohesion, and Network Range on the Transfer of Knowledge Between Organizational Units. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 1024–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; El Sawy, O.A. From IT Leveraging Competence to Competitive Advantage in Turbulent Environments: The Case of New Product Development. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 198–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, G.; Durisin, B. Absorptive capacity: Valuing a reconceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidner, D.; Gonzalez, E.; Koch, H. An affordance perspective of enterprise social media and organizational socialization. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Sun, Y.; Shen, X.-L.; Zhang, X. A value-justice model of knowledge integration in wikis: The moderating role of knowledge equivocality. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwahk, K.-Y.; Park, D.-H. Leveraging your knowledge to my performance: The impact of transactive memory capability on job performance in a social media environment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paré, L.D. Rigor in Information Systems Positivist Case Research: Current Practices, Trends, and Recommendations. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 597–636. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, R.; Gasco-Gasco, J.; Llopis-Taverner, J.; González-Ramírez, R. Information systems outsourcing: A literature analysis. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gephart, R.P. Qualitative Research and the Academy of Management Journal. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J.; Baroudi, J.J. Studying Information Technology in Organizations: Research Approaches and Assumptions. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsham, G. Interpretive case studies in IS research: Nature and method. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 1995, 4, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonova, B. Transactive memory systems and Web 2.0 in knowledge sharing: A conceptual model based on activity theory and critical realism. Inf. Syst. J. 2017, 28, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Ou, C.X.; Martinsons, M. Information technology to support informal knowledge sharing. Inf. Syst. J. 2012, 23, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrus, J.; Gannamaneni, A.; Lyytinen, K. The Impact of Openness on the Market Potential of Multi-Sided Platforms: A Case Study of Mobile Payment Platforms. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S.J.; Vidgen, R. Data triangulation and web quality metrics: A case study in e-government. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Conflict Propagation Within Large Technology and Software Engineering Programmes: A Multi-Partner Enterprise System Implementation as Case Study. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 167696–167713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, P.E.; Enoiu, E.P.; Afzal, W.; Sundmark, D.; Feldt, R. Information Flow in Software Testing—An Interview Study with Embedded Software Engineering Practitioners. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 46434–46453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Buxmann, P. Organizational Design of it Supplier Relationship Management: A Multiple Case Study of Five Client Companies. J. Inf. Technol. 2012, 27, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzum, M.; Simonsen, J. How is professionals’ information seeking shaped by workplace procedures? A study of healthcare clinicians. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.M.; Deandrea, D. How Anonymity and Visibility Affordances Influence Employees’ Decisions About Voicing Workplace Concerns. Manag. Commun. Q. 2018, 33, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C. The evolutionary implications of social media for organizational knowledge management. Inf. Organ. 2017, 27, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.L.; Rozaidi, N.A.; Eisenberg, J. Overcoming the “Ideology of Openness”: Probing the Affordances of Social Media for Organizational Knowledge Sharing. J. Comput. Commun. 2013, 19, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Miner, A.S. Vicarious Learning from the Failures and Near-Failures of Others: Evidence from the U.S. Commercial Banking Industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 687–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Visibility | Definition | Awareness Enabled | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication visibility | Visualizing the communication that was once invisible for third parties | Meta-knowledge | [17,18,32] |

| Identity visibility | Visualizing others’ identity information, including positions and departments, and having the ability to directly communicate with them | Identity information | [34] |

| Collaboration visibility | Visualizing the instrumental knowledge of collaborations on ESM | Instrumental knowledge | [18,35] |

| Process visibility | Visualizing an entire workflow and an individual’s activity status | Workflow, individual’s activity status, and task knowledge awareness | [35,36] |

| Concepts | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Vicarious Leaning in Prior Research | Vicarious Learning in the Context of ESM | |

| Models | not only refers to other people, but also to such symbolic means | refers to others’ experiences or knowledge on ESM |

| Attention | the process of selecting a specific model and determining which experience to learn, which is also called expertise seeking in other fields | the process of locating others’ experiences or knowledge on ESM |

| Retention | encoding the observed behavior in a manner the observer readily understands, and storing the behavior in memory | the process of understanding others’ experiences or knowledge and then storing it in the mind as a guide to future actions |

| Production | the transformation of these stored mental guides into action in an appropriate situation | applying learned external knowledge on ESM |

| Motivation | refers to various incentives that can prompt individuals to perform the vicariously learned behavior | refers to learners’ motivations or incentives to apply what they have learned |

| Concept | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| meta-knowledge | the knowledge of “who know whom and who know what” | [17] |

| instrumental knowledge | the knowledge about how to do something | [18] |

| virtual collaboration (i.e., collaboration occurs on ESM) | share and integrate others’ knowledge when that knowledge is primarily conveyed through media | [35] |

| task knowledge awareness | up-to-minute knowledge of who is doing what in the team | [49] |

| Key Themes | The Number of Items | Typical Item |

|---|---|---|

| communication visibility | 102 | We may communicate on the group now, or if the leader has something to share, it will be posted on DingTalk, because it is visible on the DingTalk and more convenient than communicating in offices. |

| identity visibility | 113 | Because it means to say that on the DingTalk you may have a very clear cognition about what position and which department he is in, because you can see that information. |

| collaboration visibility | 119 | This is to say that when someone has any problems, or when they are directly looking for answers in group, and if I know how to do that, I will offer guidelines about how to deal with these problems on DingTalk. |

| process visibility | 101 | I will pay attention to whether he is in the working state, such as whether he is in a meeting. |

| attention | 62 | We have someone who collects suggestions from employees. Generally, this person will post them on time. If there are too many suggestions, he will post them early. If there are not many, he will post them once every two weeks. I often pay some attention to what he posts. |

| retention | 41 | I will read some guidance documents in group. If there are any questions, I will ask my colleagues and discuss how to do this in my work. |

| production | 83 | If everyone agrees with this plan, I don’t need to use other methods. It’s easier to use this directly and less prone to errors. |

| motivation | 26 | Sometimes my colleagues will come to help me, and my heart will be more solid and the whole work will be faster. |

| Key Themes | The Number of Items | Typical Item |

|---|---|---|

| communication visibility | 103 | As to the information shared on DingTalk, you can see it at anywhere and anytime and also know who has seen it and who hasn’t. |

| identity visibility | 81 | If someone sends me a text on DingTalk, I will trust this information because I can see who he or she is in our company. |

| collaboration visibility | 129 | Some new employees who do not know their work very well will go to find some knowledge about how effectively they can do something on DingTalk. |

| process visibility | 115 | I can see the whole work process and who is responsible for what, and I will tend to discuss with them whose works are closely related to my work. |

| attention | 57 | There is a summary meeting every week, and there will be better people to share experiences, then I will generally pay attention to whether his experience is suitable for us to use |

| retention | 32 | I will be impressed if I see these similar problems and solutions on DingTalk, I don’t have to ask these questions again. |

| production | 96 | Supervisors may release some guiding working documents. These documents are generally summarized by experienced employees, and we will learn to use them. |

| motivation | 31 | People who have better employee training results and those who have made greater progress in their work performance will be publicized on DingTalk and offline. This has a certain effect on motivating the learning of other employees. |

| Vicarious Learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention | Retention | Production | Motivation | |

| Identity Visibility | Identity visibility ⇓ identity information ⇓ weak social tie, people sense-making ⇓ locate expertise, access various information | |||

| Communication Visibility | communication visibility ⇓ meta-knowledge ⇓ visual advantage ⇓ find some tacit knowledge, identify who has knowledge | communication visibility ⇓ show different technology languages, thought-worlds ⇓ shared mental modes | ||

| Collaboration Visibility | collaboration visibility ⇓ instrumental knowledge, mass discussion ⇓ reduce efforts to interpret and synthesize new insights, simplify the domain-specific knowledge | collaboration visibility ⇓ visualize various instrumental knowledge and different perspectives ⇓ multiplies the opportunities to combine others’ knowledge with existing knowledge | collaboration visibility ⇓ detailed instrumental knowledge ⇓ improve self-efficacy | |

| Process Visibility | process visibility ⇓ workflow information, task knowledge awareness ⇓ comprehend the necessary others’ knowledge, improve collaboration | process visibility ⇓ workflow information, task knowledge awareness ⇓ see the gaps and opportunities, understand other perspectives | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Gauthier, J. The Sustainable Positive Effects of Enterprise Social Media on Employees: The Visibility and Vicarious Learning Lens. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072855

Sun Y, Ding Z, Zhang Z, Gauthier J. The Sustainable Positive Effects of Enterprise Social Media on Employees: The Visibility and Vicarious Learning Lens. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072855

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yuan, Zhebin Ding, Zuopeng (Justin) Zhang, and Jeffrey Gauthier. 2020. "The Sustainable Positive Effects of Enterprise Social Media on Employees: The Visibility and Vicarious Learning Lens" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072855

APA StyleSun, Y., Ding, Z., Zhang, Z., & Gauthier, J. (2020). The Sustainable Positive Effects of Enterprise Social Media on Employees: The Visibility and Vicarious Learning Lens. Sustainability, 12(7), 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072855