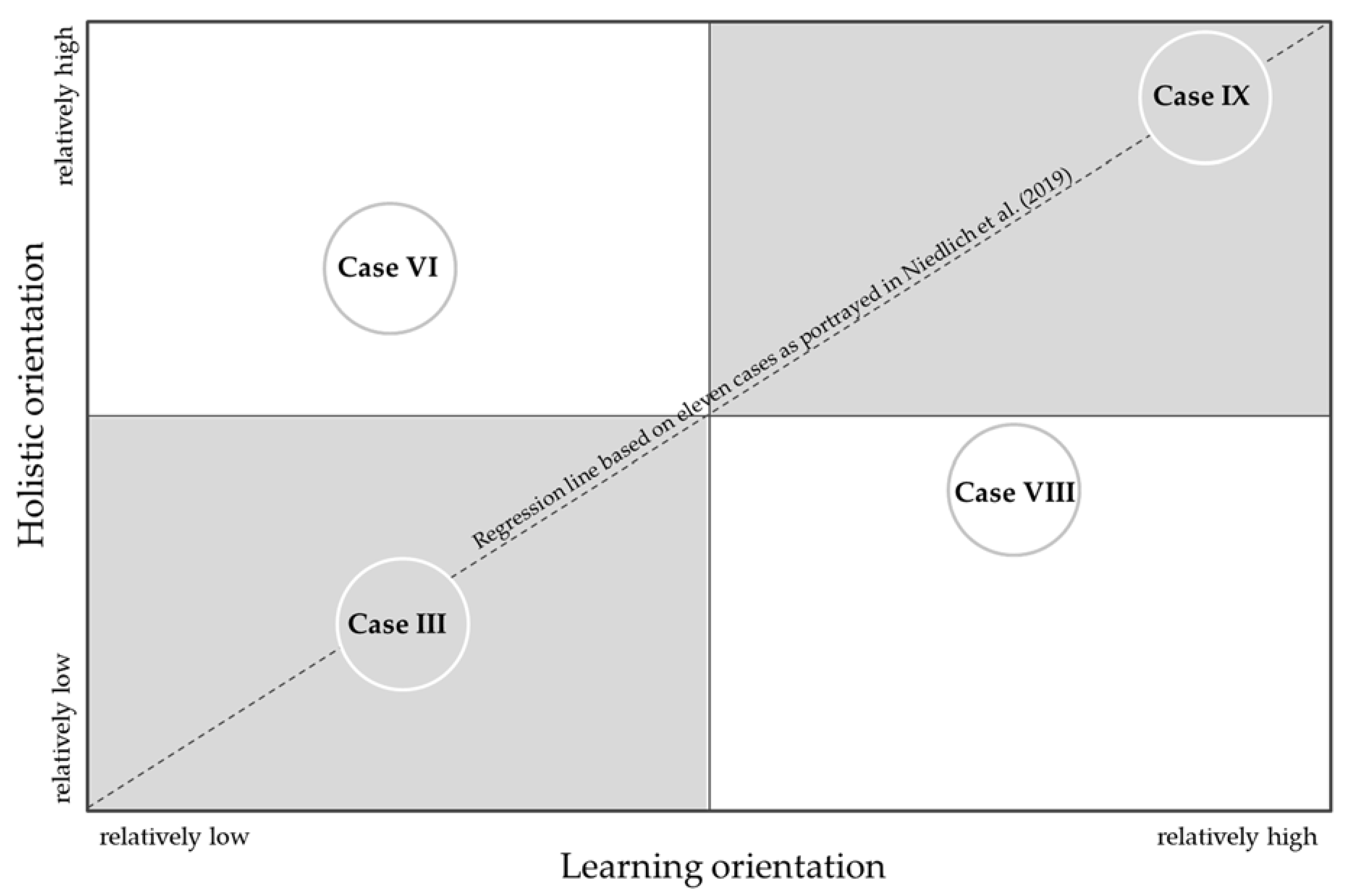

A comparative analysis of the two pairs of HEIs provides the following insights in respect of the effects of cultural orientation (holistic and learning orientation) on the functional requirements of sustainability governance, as illustrated by the sustainability governance equalizer. The two cases constituting each pair are first described separately and then compared with each other.

4.1. Cases VI and VIII: Strong Holistic Orientation and Pronounced Learning Orientation vs. Low Holistic and Distinct Learning Orientation

Cases VI and VIII were used to gain an impression of the extent to which a difference in the degree of the two cultural orientations impacts on governance structures. Case VI had a stronger focus on holistic orientation and case VIII had a more pronounced focus on learning orientation. While the SD structures and processes that were set up at the two HEIs appear quite similar from the outside, significant differentiation was found. The case descriptions and analyses below explore and draw out, in particular, the differences relating to the manner of structures’ outreach into their institution, how autonomous they are and what their conceptual focus is.

4.1.1. Case VI: Strong Holistic and Low Learning Orientation

HEI case no. VI has between 5000 and 10,000 employees and between 25,000 and 50,000 students in 100–200 different study programs with a broad spectrum, and is located in an urban environment. The beginning of its sustainability process can be traced back almost 30 years to the early 1990s when concerns about the scarcity of global resource were raised by campus operations staff. Energy efficiency has been on the construction department’s agenda ever since, with other environmental issues being discussed in a working group specially established for this purpose. From there, sustainability as a concept evolved in HEI VI and was recognized by senior management in recent years as a guiding principle for the whole institution, with the potential to promote and underline its reputation for scientific excellence. A center of expertise was established as the central SD governance body, mediating between senior management and the rest of the HEI. It is comprised of five strategic working groups covering the whole institution and with participation by academic staff, administrative staff and students.

Many activities aimed at creating a sustainable HEI were initiated, including the preparation of a sustainability report and the development of a mission statement. Nevertheless, the HEI’s overall SD process is said to be lacking in terms of oversight of the various activities, the transfer of principles into day-to-day practices and broad participation.

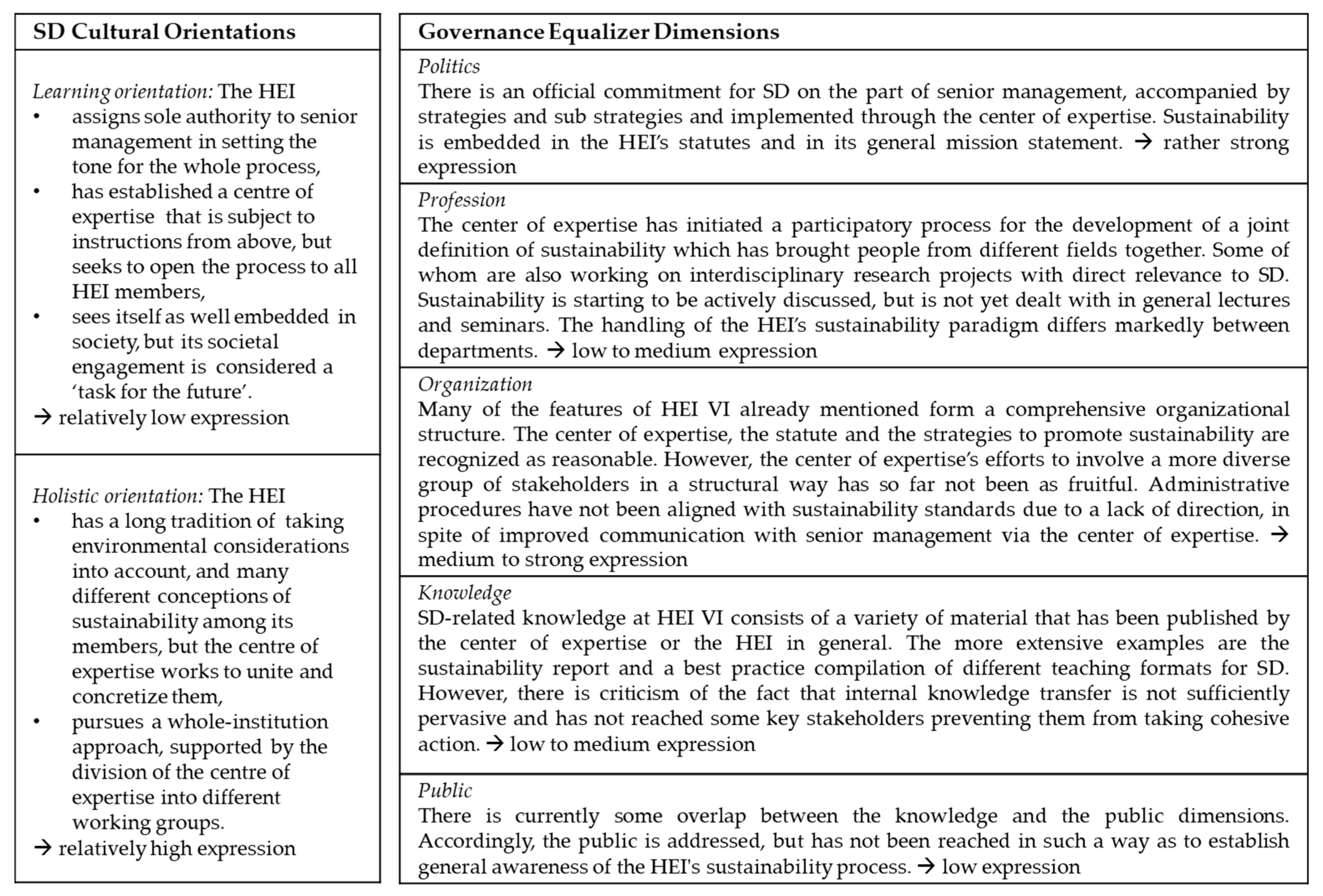

Further descriptions of the case are given in

Figure 5, which sets the HEI’s cultural orientation next to its governance equalizer dimensions. It creates a more comprehensive picture of the HEI’s relatively highly developed

holistic orientation and relatively underdeveloped

learning orientation in relation to SD. Taking all these aspects into consideration, in what ways they might have influenced each other in the particular context of HEI VI can then be discussed.

In light of the cultural orientation, some of the governance equalizer values do not come as a surprise. The HEI’s low learning orientation, and in particular the fact that responsibility for SD is mainly assigned to senior management can facilitate and accelerate processes such as embedding SD in the mission statement (→ politics), especially when it is paired with a whole-institution approach (→ organization, profession). However, in terms of long-term prospects, the success of such a top–down process depends on whether HEI members are willing and able to commit to a mission statement that they were not involved in developing. In order to bring a top–down strategy to life (→ politics, organization, public), it may be necessary either to allocate additional personnel specific responsibility for achieving the objectives or to re-organize responsibilities, because it is unlikely that staff will have too much time for unexpected tasks. Otherwise, a low learning orientation combined with a high holistic orientation towards SD might come in handy when it comes to announcing SD principles for the HEI as a whole, but it does not guarantee that such principles will be eagerly adopted.

As described above, the center of expertise has begun to promote an institution-wide conversation on SD (→ profession, knowledge) because of its belief in holistic transformation, but the power to make real changes to fundamental processes still lies with senior management, which does not take things quite so far. The thoughtfully constructed and broadly established center of expertise, which is striving to coordinate a diligent and coherent process (→ organization), may be in danger of becoming a toothless tiger. This might lead to problems for all the equalizer dimensions, since their development seems to depend on that very structure.

4.1.2. Case VIII: Low Holistic and Profound Learning Orientation

HEI VIII is also located in an urban environment. It also has 25,000–50,000 students across 100–200 different study programs and employs up to 5000 people. Sustainability became an issue at this HEI at the beginning of the 1990s, sparked by employees in the administration who demanded that the institution take meaningful steps to reduce its energy consumption, much like case VI. At HEI VIII, this led to a long process of ISO certification and ultimately resulted in the introduction of the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). Several small sustainability teams were entrusted with the development of energy saving measures at the departmental level; these had a great impact and helped the whole process to evolve.

Nowadays, there is a staff unit for sustainability and energy with approximately ten employees, who are recognized as important drivers of the sustainability process. The concept of sustainability has broadened over time. Through, inter alia, the engagement of a student initiative, the focus has been shifted from campus management resource concerns towards a comprehensive approach including research, teaching and outreach. A research center acted as the key catalyst for sustainable development in research, generally accessible courses were established with a clear relevance for sustainability, and participation in sustainability networks was increased.

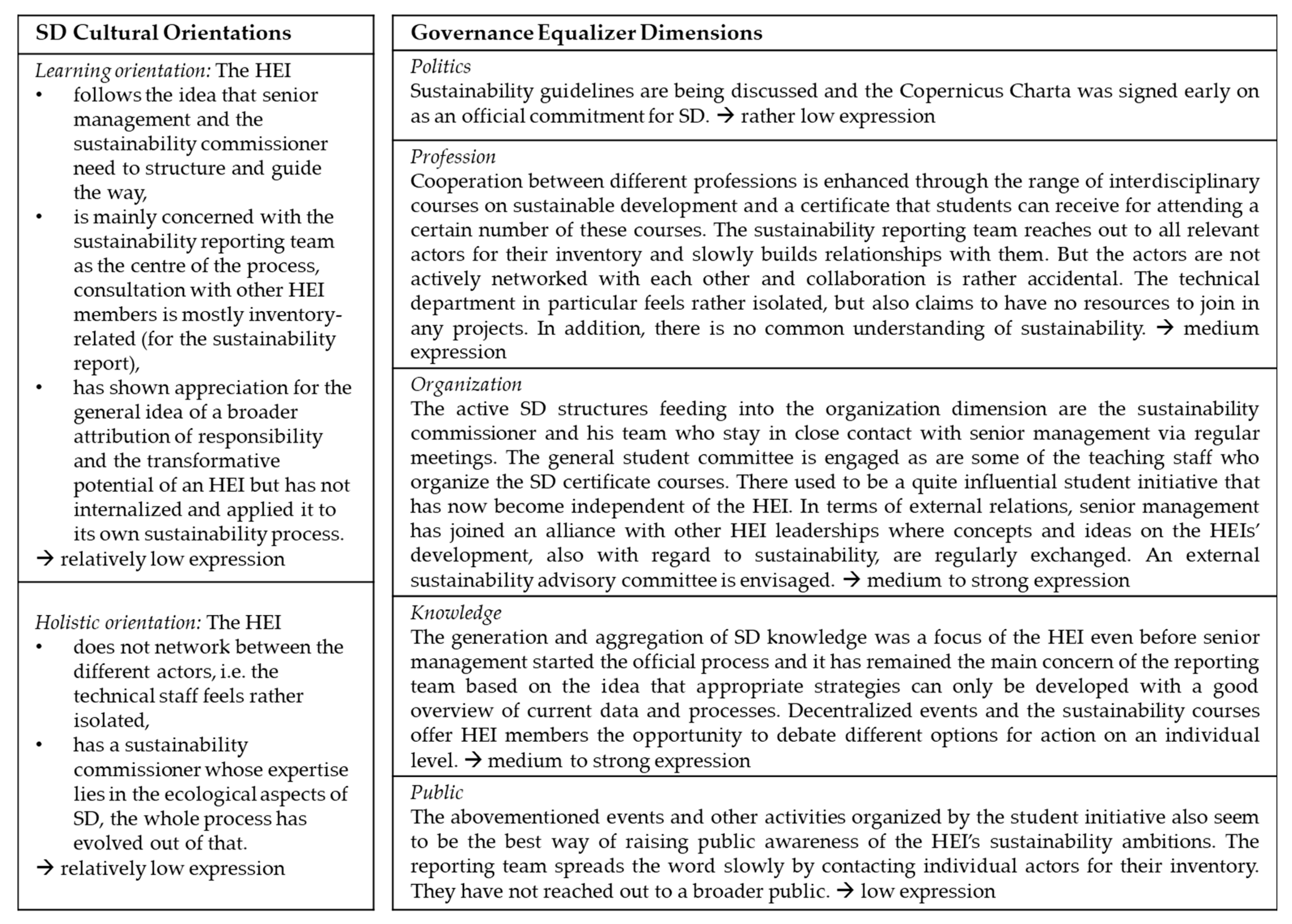

As stated above, HEI VIII is an institution with a relatively low

holistic orientation and a relatively high

learning orientation towards SD. Therefore, to some extent, it represents the reverse set-up of HEI VI. A closer look at the governance equalizer dimensions for HEI VIII, as summarized in

Figure 6, might help to pinpoint the possible effects of the different cultural environment that is indicated on the left side of the figure.

Throughout the five dimensions, the high learning orientation seems to have had an impact that is manifested in a collaboratively developed mission statement (→ politics, organization, profession, public) and also in the way the staff unit has been arranged (→ organization, knowledge). It has close links with senior management but is also working with sustainability teams in the HEI’s different areas (→ profession). Responsibility for SD is spread between them and not completely centralized, which certainly increases public attention for the topic (→ public). The HEI’s learning orientation, and specifically its conception of its own role in society as an SD educator, has enabled the development of new concepts of knowledge transfer (→ knowledge, public).

The main gap highlighted by the governance equalizer is insufficient coherence and shared understanding amongst HEI members with regard to SD (→ profession). Against the backdrop of a long tradition of ecological optimization and the ongoing focus on energy and resources in the staff unit, it seems logical that, despite collaborative processes, HEI members are irritated by aspects of the institution’s concept of sustainability because the holistic orientation is somewhat limited. Nonetheless, the HEI has been able to establish solid overarching governance structures.

4.1.3. Comparison of HEIs VI and VIII

The strongest equalizer dimensions for HEIs VI and VIII are politics and organization. Profession, knowledge and public are all developed to a medium level at both HEIs. At first sight, the different organizational cultures do not appear to have had a particular impact on HEI sustainability governance. However, as the individual case descriptions have shown, the HEIs’ SD structures vary with regard to some important details. This is most prominently expressed in the relations identified between the main SD actors and the potential for these relations to be shaped by the culture of the organization (especially its learning orientation).

HEI VI with its center of expertise and HEI VIII with its staff unit have set up structures that aim to introduce SD measures into all fields of activity. They both have close links with senior management and are equipped with roughly the same number of staff. However, there are differences in their strategic alignment and integration, i.e., the way functions are organized as shown in the equalizer. These relate to three major aspects, which seem to go hand in hand with the HEIs’ cultural orientations: the manner of their outreach into the institution, their degree of autonomy and their conceptual focus.

By ‘manner of outreach’, we mean the strategies adopted by the two bodies that might help them to gain acceptance for (common) SD activities in the HEI’s community. The idea that responsibility for SD should be spread across several pairs of shoulders (→ attribution of responsibility, as part of the learning orientation), and that these shoulders need to have some level of autonomy, seems to have driven HEI VIII towards more open and extensive structures. Certainly, the staff unit is the team with primary responsibility; it is also dependent on senior management decisions. But through the sustainability teams in different departments, a unifying steering committee and a good connection with the biggest and highly active student and staff sustainability initiative, they have the potential to shape a coherent and collaborative process that receives a broad welcome. The institution’s learning orientation has thus enabled reasonable structures in terms of profession, organization, and potentially public.

This is seemingly less the case in HEI VI, where the working groups are an integral part of the center of expertise, are made up of appointed members and, therefore, act less independently. The structure is not bad per se, but it could be argued that greater awareness of and trust in a broader range of perspectives could help with implementation. This is evident at HEI VI in certain situations where senior management demonstrates a lack of appreciation for the achievements of extensive student engagement. The center of expertise, however, is working on overcoming this problem and is already considered a good contact point for SD issues by other HEI members. These efforts might eventually lead to changes in the HEI’s cultural orientations. This would provide an example of how governance structures can influence an HEI’s cultural orientation over time.

The conceptual focus refers to the aspects of SD that are being addressed by the staff unit or the center of expertise and their underlying conceptions of sustainability. Even though both HEIs originally focused on improving ecological rather than other aspects of sustainability, as the cultural orientations show, HEI VI is now applying a multi-dimensional approach more consistently than HEI VIII. This can be linked to the different staff configurations that are responsible for SD, and their backgrounds. On the one hand, the staff unit at HEI VIII has evolved from a staff unit for energy to a staff unit for sustainability and energy and was, therefore, built around—and still is dominated by—an expertise in energy and resource issues. The center of expertise in HEI VI, on the other hand, was conceived as an interdisciplinary team from the beginning and hence has been better able to identify with a multi-dimensional concept of sustainability.

When looking at overall SD governance at both HEIs, however, this head start has not resulted in a long-term advantage or disadvantage for HEI VI. This is doubtless due to a number of factors. It is suspected, though, that the conception of sustainability, which is only one part of the holistic orientation, might have less influence on SD governance than the second part, the relevance and scope of organizational change. At least regarding the initiation of the process, it seems to be more important for an HEI’s SD governance to take an institution-wide approach than have a comprehensive conception of sustainability when structures are created, which can happen at any level and in any part of the institution. After all, the whole-institution approach is an aspect that these two HEIs have in common and that so far seems to have guided them in relation to structures. However, comparison of the two cases shows that the learning orientation needs to be factored in when designing the whole-institution approach and that a holistic orientation alone does not lead to all-encompassing structures and processes.

This last aspect suggests that the discrepancies between the two cultural assumptions, which were found only in HEIs VI and VIII out of the sample of eleven, are not only uncommon, but also, to some extent, counterproductive. A more linear evolution in orientation appears more desirable, although it does not necessarily mean an easy route of SD implementation as the comparison of the next two cases will illustrate.

4.2. Cases III and IX: Low Holistic and Learning Orientation vs. Distinct Learning and Holistic Orientation

Cases III and IX are intended to provide insight into how very different stages of cultural orientation affected governance structures at the HEIs in question. Case III had one of the lowest learning and holistic orientations and case IX one of the highest. Since they both represented cases where the relationship between holistic and learning orientation was linear, it was deemed of particular interest to investigate how these individual HEIs at the opposite ends of the proposed cultural orientation spectrum translate their cultures into governance measures. Many differences were identified between the two HEIs, but the most distinctive aspect arising from the comparison was their different approaches towards knowledge work in the context of SD as the following outlines illustrate.

4.2.1. Case III: Low Holistic and Low Learning Orientation

HEI III is an urban HEI with 25,000–50,000 students in 100–200 study programs and employs between 5000 and 10,000 people. The sustainability process was only begun in 2013 with a senior management decision to appoint a sustainability commissioner. Prior to that, a very active student initiative had been the only driver of sustainability-related change at an institutional level. The sustainability commissioner, who is a professor and, therefore, does not have extra time resources, has been given the support of a research assistant and the task of supervising a 5 year sustainability reporting process with the aim of proposing appropriate measures. By the time the interviews took place, the team had almost finished its inventory and was about to start using it to derive strategies. One central idea is the establishment of a Green Office for process stabilization and continuity.

Apart from this central process, different individual activities are taking place. The abovementioned student initiative and the general student committee organize SD events, promote sustainable consumption on campus and search for innovative mobility solutions. A mixed group of HEI members is focused on making the campus bike friendly. As regards teaching, practical interdisciplinary sustainability courses are being offered.

This description of HEI III paints the picture of an HEI that has set a sustainability process in motion with a comparatively low

learning orientation towards SD and an initially rather one-dimensional and top–down approach.

Figure 7 reflects on some further insights into the HEI’s cultural orientation and outlines the governance equalizer dimensions.

HEI III finds itself at a point in its sustainability process that can easily be traced back to its cultural orientation. The learning orientation in particular seems to be clearly reflected in the current governance. Senior management and the sustainability commissioner and his team preferred to learn about their institution before they learned with the institution when they decided that a sustainability report should be produced before any other centralized sustainability activities were pursued so that the latter could be based on reliable information (→ profession, organization, knowledge). It is arguable whether this was a wise or even necessary decision, and, in the long run, this will be illustrated by what the HEI eventually makes of the process that it has started, which it has mostly kept in the presidential office. For now, the activities taking place in addition to that official top–down process such as the sustainability certificate that students can gain—organized by some teaching staff, or other student or professional or technical staff-based initiatives—are trying in vain to find allies in their HEI.

Instead of supporting the building of an SD network within the HEI and starting to share responsibilities, senior management prefers to join external sustainability networks and seek alliances with elite representatives from other HEIs. Both are a potential source of valuable knowledge on SD implementation, but the exclusive involvement of senior management underlines once more the HEI’s low organizational learning orientation. The establishment of a Green Office (a student-led sustainability bureau with HEI funding) may succeed in breaking with this pattern (→ organization). So long as it is not primarily an extension of the senior management but has some autonomy, it could be a good way to open up the process to the whole HEI community (→profession, public).

Taking the HEI’s holistic orientation into consideration, it has certainly had an impact on the ongoing process. The HEI does intend to apply a multi-dimensional approach to sustainability and to integrate it into its different fields of activity, but this concept was formulated only relatively recently. Besides the commissioner and his team, who are responsible for SD across the whole institution (→ organization), there are hardly any activities that indicate a comprehensive approach is being taken (→ politics). Due to his area of expertise, the sustainability commissioner mainly takes content-based responsibility for ecological topics. In this case, this has hardly any effect on the process within the HEI as a whole, as there has thus far been virtually no contact with the technical staff of the HEI (→profession). The relatively low learning orientation is, therefore, preventing the equally low holistic orientation at HEI III from having an impact on procedures.

4.2.2. Case IX: High Holistic and High Learning Orientation

HEI IX is the only rural HEI in the selection. It has less than 1000 employees, between 5000 and 10,000 students and offers study programs in a narrow course spectrum. In 2013, some committed individuals at HEI IX started submitting requests to senior management for the HEI to promote sustainability. Some responsibility for SD was created in the form of target agreements between the HEI and the federal state. Institution-wide workshops in 2015 introduced further ideas about a sustainable HEI and were followed by the appointment of a sustainability commissioner, also a professor, who was provided with some personnel resources. The sustainability commissioner coordinates a SD working group that has prepared sustainability guidelines that were discussed in another institution-wide workshop including senior management and are being processed by the HEI senate.

The working group, which has a good mix of HEI members, and a student initiative host small events and participate in national sustainability action days. On the administrative side, sustainability considerations have impacted on a number of procurement decisions, and connections have been made between SD and the HEI’s policies (e.g., gender equality, family friendliness, inclusion).

HEI IX has the most concise orientation of the four towards sustainability.

Figure 8 provides more detailed information on both the cultural orientation and the governance equalizer. The interrelationship between the two is discussed below.

Interestingly, the governance equalizer does not actually portray HEI IX as having advanced sustainability structures and processes, as the organization’s culture has suggested. However, that does not necessarily mean that the cultural orientations did not have an impact. Closer examination reveals that the structures and processes that have been implemented or are about to be implemented, especially in relation to politics and organization, do reflect a relatively high holistic and learning orientation.

The understanding that actors from all the different groups of stakeholders and fields of activity should have the opportunity to participate in the HEI’s sustainability process is clearly expressed in the way the overall process has been executed so far. Several institution-wide workshops were held, which, among other things, resulted in common sustainability guidelines (→ politics, profession, public). The sustainability commissioner coordinates an open SD working group (→ organization), and student involvement is much appreciated, albeit difficult to maintain. From the very beginning, sustainability was considered to be a multi-dimensional concept, and this is well reflected in the guidelines. The steps may be small, but they set the tone for further development of the HEI’s sustainability governance. This is especially true for the knowledge dimension, the least prominent equalizer dimension at HEI IX. This case indicates that participatory processes not only take time, but also require staff resources, with which HEI IX is the least equipped out of the four cases presented here. Apart from that, this HEI certainly has some advantages—shorter distances, a smaller range of disciplines—which facilitate some processes, since it is by far the smallest of the four HEIs.

4.2.3. Comparison of HEIs III and IX

At first sight, there are some commonalities in the two institutions’ sustainability processes. They started around the same time after small groups or individual HEI members became engaged with sustainability. Once they had been successful in putting sustainability on the HEI’s agenda, the senior management team in question decided to appoint a sustainability commissioner to be responsible for coordinating and overseeing the whole process. What appears to be quite different, though, is the conception of how best to set up the process. This is where the cultural orientations divide the two HEIs.

Although in the case of both HEIs, it has been a similarly short time since they initiated their sustainability processes, they have already adopted very different positions. It can be assumed that their cultural orientations have played a role in organizational development towards sustainability. HEI III went straight to action with a clear vision and introduced structures that should form the basis for a well-founded process. From an operational perspective, this makes sense, but the essence of sustainability seems to have been neglected or not fully internalized yet. This means that sustainable development, with its various substantive and methodological components, has either not been fully explored or has been reduced to distinct individual aspects. Even though the will to implement a multi-dimensional understanding of sustainability in all areas of the institution (→ holistic orientation) is generally present, the HEI is still faced with the challenge of transferring this will to the current elite and discrete structures and thus developing them further to make them more accessible. As was the case at HEI IX, the HEI’s organization and profession dimensions would certainly benefit from such a concept.

HEI IX started with somewhat less concrete activity, but active stakeholder participation ensured that there was broad agreement with the central decision by senior management to appoint a sustainability commissioner. This openness signals to the members of the HEI that their engagement is wanted and that it can shape important aspects of SD. This also makes it easier to replicate the organizational culture amongst HEI members and encourage it to evolve collectively. The working group has promoted regular interdisciplinary exchange and collaboration (→ organizational learning orientation). Nonetheless, there is one equalizer dimension that has been developed notably further at HEI III than HEI IX: knowledge.

Maybe unexpectedly, this is also where the differences between the ways the HEIs’ governance has been shaped by their cultural orientations are most obvious. The HEIs seem to apply quite different approaches towards knowledge and knowledge work in the context of SD. HEI III, with its focus on knowledge generation, has introduced a structure, namely the sustainability reporting team, which is efficient at gathering data and identifying important contributors for the report. Their knowledge work is a highly centralized and isolated process that does not open up to the potential for common exploration with diverse stakeholders on diverse topics, which is the approach taken by HEI IX. The combination of low holistic orientation and low learning orientation leads HEI III to a very target-oriented, and in that sense efficient, knowledge dimension that, however, will inevitably reach its limits when all information has been gathered. High holistic and learning orientations have helped HEI IX to lay groundwork that gives knowledge the chance to expand at a variety of levels. The downside of this approach is certainly that it takes much more effort in relation to proactive stakeholder engagement and coordination and, therefore, has not yet resulted in a strong knowledge dimension for HEI IX. This comparison of knowledge work captures the distinct styles of SD implementation at both HEIs and corresponds well with the aforementioned aspects. It also highlights the different qualities that can be found within a single equalizer dimension and encourages an integrative approach towards the governance equalizer when introducing governance measures.

Overall, neither of the two HEIs has addressed any of the equalizer dimensions in an all-encompassing way. They have made approximately the same amount of progress, if that is even comparable, and are now at a point where the implementation of concrete and significant measures is required. Their SD processes are relatively young and will need some more time to unfold. It remains to be seen whether they will manage to either seize or change their current functions and culture.