Study Abroad in Support of Higher Education Sustainability: An Application of Service Trade Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Declining Sustainability of Higher Education

2.2. Why Service Trade Strategy on Higher Education? Intangibility and Convergence

2.3. Undergraduate Degree-seeking Study Abroad Programs as an Example of Service Trade

2.4. Application of Service Trade Strategy on Undergraduate Degree-Seeking Study Abroad Programs

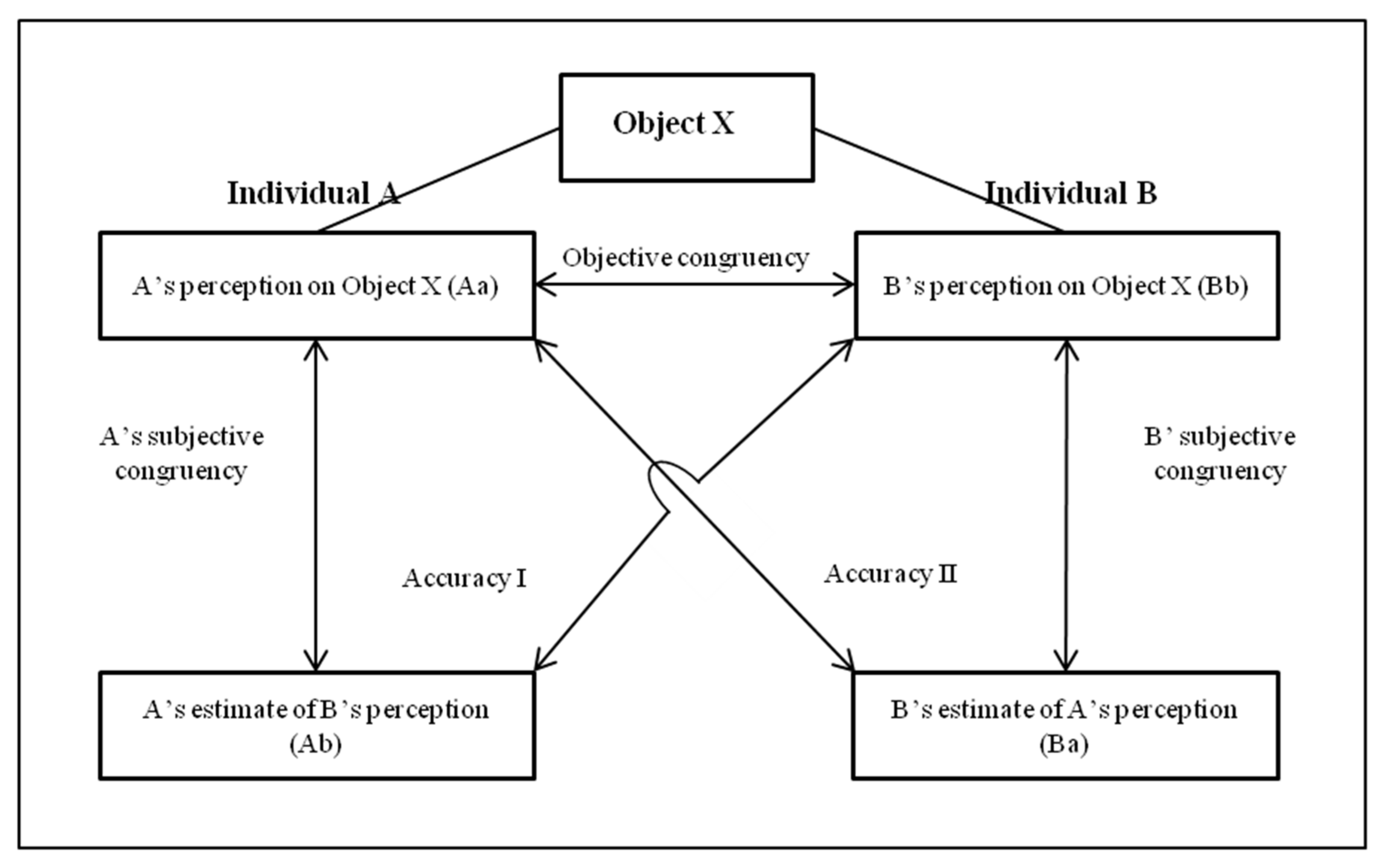

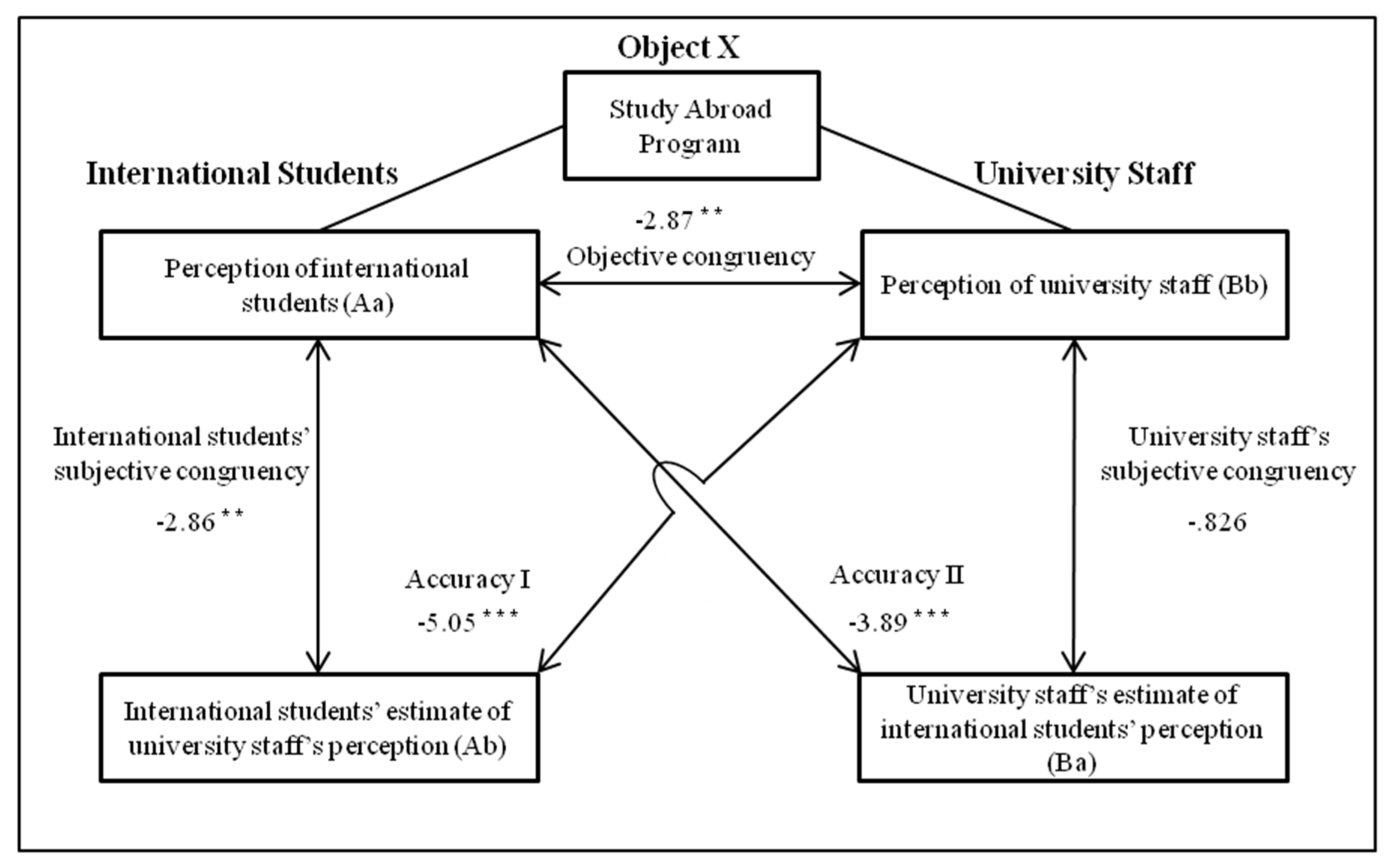

2.5. Application of Service Trade Strategy with Perceptual Difference Analysis: Co-Orientation Model

2.6. Development of Research Questions

- RQ1: How different are international students’ and university staff’s perceptions regarding the importance of the cost of studying abroad (COST) in the selection of an undergraduate degree-seeking study abroad program destination?

- RQ2: How different are international students’ and university staff’s perceptions on the importance of education (EDUC) in the selection of an undergraduate degree-seeking study abroad program destination?

- RQ3: How different are international students’ and university staff’s perceptions on the importance of hospitality (HOSP) in the selection of an undergraduate degree-seeking study abroad program destination?

- RQ4: How different are international students’ and university staff’s perceptions on the importance of foreigner friendliness (FNFR) in the selection of an undergraduate degree-seeking study abroad program destination?

- RQ5: How different are international students’ and university staff’s perceptions on the importance of location (LCTN) in the selection of an undergraduate degree-seeking study abroad program destination?

3. Method

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Questionnaire Structure

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Co-Orientation Research Model

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Validity and Reliability

4.1.1. Convergent Validity: Selection Factors Preferred by International Students

4.1.2. Convergent Validity: Factors Perceived by Korean Universities as Being Important for International Students

4.1.3. Discriminant Validity

4.1.4. Reliability

4.2. Objective Congruency

4.3. Subjective Congruency

4.4. Accuracy

4.4.1. Accuracy I (Ab/Bb)

4.4.2. Accuracy II (Aa/Ba)

4.5. Co-orientation Status

4.6. Analyses of Research Questions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Scope of Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Location | Institution | |

|---|---|---|

| Public | Seoul | Seoul National University |

| Seoul | University of Seoul | |

| Private | Seoul | Hankuk University of Foreign Studies |

| Seoul | Hansung University | |

| Seoul | Korea University | |

| Seoul | Konkuk University | |

| Seoul | Kyung Hee University | |

| Seoul | Myongji University | |

| Seoul | Sahmyook University | |

| Seoul | Sangmyung University | |

| Seoul | Sejong University | |

| Seoul | Sogang University | |

| Women’s University | Seoul | Sookmyung Women’s University |

| Seoul | Ewha Woman’s University | |

| Science and Technology | Pohang | Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH) |

| Daejeon | Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) |

References

- Samir, K.C.; Lutz, W. The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 42, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J. The fourth industrial revolution, knowledge production and higher education in South Korea. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Dive. Available online: https://www.educationdive.com/news/how-many-colleges-and-universities-have-closed-since-2016/539379/ (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Gribble, C. Policy options for managing international student migration: The sending country’s perspective. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2008, 30, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, H.Ø. China’s recruitment of African university students: Policy efficacy and unintended outcomes. Glob. Socit. Edu. 2013, 11, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, C.M.; Sabzalieva, E. The politics of the great brain race: Public policy and international student recruitment in Australia, Canada, England and the USA. High Educ. 2018, 75, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, A. Role of higher education institutions (HEIs) in developing management capacity in the public sector: Customising the curriculum to build public service cadres. In Proceedings of the 13th Public Sector Trainer’s Forum Conference, Birchwood Hotel, South Africa, 14–16 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zepke, N. Student engagement research in higher education: Questioning an academic orthodoxy. Teach. High. Educ. 2013, 19, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Bandyopadhyay, K. Factors influencing student participation in college study abroad programs. J. Int. Educ. Res. 2015, 11, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, R.; Alonso-Almeida, M. Sustainability reporting in higher education: Interconnecting the reporting process and organisational change management for sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8881–8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fien, J. Advancing sustainability in higher education: Issues and opportunities for research. High. Educ. Policy 2002, 15, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Lukman, R.; Lozano, F.J.; Huisingh, D.; Lambrechts, W. Declarations for sustainability in higher education: Becoming better leaders, through addressing the university system. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 48, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinko, C.A. Integrating sustainability in higher education: A generic matrix. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.M.; Noh, E.J.; Lee, J. Study abroad programs as a service convergence: An international marketing approach. Serv. Bus. 2018, 12, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, D.; Dripps, W.; Nicholas, K.A. Teaching and learning sustainability: An assessment of the curriculum content and structure of sustainability degree programs in higher education. Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Korea Times. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2018/03/181_246221.html (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Knight, J. International education hubs: Collaboration for competitiveness and sustainability. New Direc. High. Educ. 2014, 2014, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; Chen, T.F. The relationships among experiential marketing, service innovation, and customer satisfaction—a case study of tourism factories in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Talabani, H.; Kilic, H.; Ozturen, A.; Qasim, S.O. Advancing medical tourism in the United Arab Emirates: Toward a sustainable health care system. Sustainability 2019, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakurár, M.; Haddad, H.; Nagy, J.; Popp, J.; Oláh, J. The Service Quality Dimensions that Affect Customer Satisfaction in the Jordanian Banking Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Monferrer, D.; Segarra, J.R.; Estrada, M.; Moliner, M.Á. Service quality and customer loyalty in a post-crisis context. Prediction-oriented modeling to enhance the particular importance of a social and sustainable approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Bi, H.; Law, R. Influence of coupons on online travel reservation service recovery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; In Veronica Fong, H.; Tingchi, L.M. Understanding perceived casino service difference among casino players. Int. J. Comtemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 753–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Reiter, U.; Hannuksela, M.M.; Gabbouj, M.; Perkis, A. Perceptual-based quality assessment for audio–visual services: A survey. Signal Proceed. Image Commun. 2010, 25, 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J.; Gatling, A.; Kim, J.S. The effect of workplace spirituality on hospitality employee engagement, intention to stay, and service delivery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 35, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. Does competency-based education with blockchain signal a new mission for universities? J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2019, 41, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernz, C.; Thakur Wernz, P.; Phusavat, K. Service convergence and service integration in medical tourism. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.B.; Nielsen, S. The role of top management team international orientation in international strategic decision-making: The choice of foreign entry mode. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. Sustainability, higher education and the learning society. Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. University presidents’ conceptualizations of sustainability in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiró, P.S.; Raufflet, E. Sustainability in higher education: A systematic review with focus on management education. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Xue, H.; Yuen, K.F.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K. Assessing the vulnerability of logistics service supply chain based on complex network. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.Y.; Yeo, G.T. Evaluation of transshipment container terminals’ service quality in Vietnam: From the shipping companies’ perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, H.; Prybutok, V.R.; Zhang, X. The moderating effect of occupation on the perception of information services quality and success. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2010, 58, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamsi, A.; Andras, P. User perception of Bitcoin usability and security across novice users. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2019, 126, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A.; Nejad, M.G.; Sreejesh, S.; Mitra, A.; Sahoo, D. The impact of customer’s perceived service innovativeness on image congruence, satisfaction and behavioral outcomes. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2015, 6, 288–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, I.; Shin, M.M.; Lee, J. Service evaluation model for medical tour service. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianqiu, Z.; Mengke, Y. Internet plus and networks convergence. Chin. Commun. 2015, 12, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. Broadcasting and telecommunications industries in the convergence age: Toward a sustainable public-centric public interest. Sustainability 2018, 10, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, G.; Guzzo, R. Customer satisfaction in the hotel industry: A case study from Sicily. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2010, 2, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Duarte, C.; Vidal-Suárez, M.M. External uncertainty and entry mode choice: Cultural distance, political risk and language diversity. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quer, D.; Claver, E.; Rienda, L. Political risk, cultural distance, and outward foreign direct investment: Empirical evidence from large Chinese firms. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, J.R. Trade in producer services: A Heckscher-Ohlin approach. J. Policy Econ. 1989, 97, 1180–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, W.J.; Nicolaidis, K. Ideas, interests, and institutionalization: “trade in services” and the Uruguay Round. Int. Organ. 1992, 46, 37–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverelli, C.; Fiorini, M.; Hoekman, B. Services trade policy and manufacturing productivity: The role of institutions. J. Int. Econ. 2017, 104, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.V.; Van Der Velde, M. Operations as marketing: A competitive service strategy. J. Oper. Manag. 1991, 10, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. Making relationship marketing operational. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1994, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, R.; Kallenberg, R. Managing the transition from products to services. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2003, 14, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, I. Service innovation strategy and process: A cross-national comparative analysis. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 234–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, H.W.; Gebauer, H. Exploring the alignment between service strategy and service innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Ma, Z.; Qi, L. Service quality and customer switching behavior in China’s mobile phone service sector. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.W. Consumer behavior on Facebook: Does consumer participation bring positive consumer evaluation of the brand? EurMed. J. Bus. 2014, 9, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Tehseen, S.; Parrey, S.H. Promoting customer brand engagement and brand loyalty through customer brand identification and value congruity. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2018, 22, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, R.M.; Fry, G.W.; Stallman, E.M.; Josić, J.; Jon, J.E. Study abroad for global engagement: The long-term impact of mobility experiences. Intercult. Educ. 2009, 20, S29–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.M.; Pei, Y.L.; Ran, B.; Kang, J.; Song, Y.T. Analysis on the higher education sustainability in China based on the comparison between universities in China and America. Sustainability 2020, 12, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, P.; Schnusenberg, O.; Goel, L. Marketing study abroad programs effectively: What do American business students think? J. Int. Educ. Bus. 2010, 3, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.O.; Alves, H.B.; Raposo, M.B. Understanding university image: A structural equation model approach. Int. Rev. Pub. Nonprofit Mark. 2010, 7, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren-Gatfield, R.; Hyde, M. An Examination of Two Case Studies Used in Building a Decision-Making Model. Int. Educ. J. 2005, 6, 555–566. [Google Scholar]

- María Cubillo, J.; Sánchez, J.; Cerviño, J. International students’ decision-making process. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringe, F. University and course choice: Implications for positioning, recruitment and marketing. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, T. Critical success factors for international education marketing. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 1998, 12, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moogan, Y.J.; Baron, S.; Harris, K. Decision-making behaviour of potential higher education students. High. Educ. Q. 1999, 53, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navrátilová, T. Analysis and comparison of factors influencing university choice. J. Compet. 2013, 5, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, I.F.; Matzdorf, F.; Smith, L.; Agahi, H. The impact of facilities on student choice of university. Facilities 2003, 21, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M. Marketing education: A review of service quality perceptions among international students. Int. J. Comtemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanka, T.; Quintal, V.; Taylor, R. Factors influencing international students’ choice of an education destination–A correspondence analysis. J. Mkt. Highr. Educ. 2006, 15, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutar, G.N.; Turner, J.P. Students’ preferences for university: A conjoint analysis. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2002, 16, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli Yamamoto, G. University evaluation-selection: A Turkish case. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2006, 20, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. What attracts mainland Chinese students to Australian higher education. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innov. Develop. 2007, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beneke, J.; Flynn, R.; Greig, T.; Mukaiwa, M. The influence of perceived product quality, relative price and risk on customer value and willingness to buy: A study of private label merchandise. J. Prod. Bran. Manag. 2013, 22, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noblet, C.; Lindenfeld, L.; Anderson, M. Environmental worldviews: A point of common contact, or barrier? Sustainability 2013, 5, 4825–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajieh, P.C.; Uzokwe, U.N. Effective application of the co-orientation communication model in disseminating agricultural information: A review. Asian J. Agri. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2014, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, J.M.; Chaffee, S.H. Interpersonal approaches to communication research. Amer. Behav. Scist. 1973, 16, 469–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.J.; Sethuraman, K.; Lam, J.Y. Impact of corporate social responsibility dimensions on firm value: Some evidence from Hong Kong and China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Education in Korea. Available online: https://www.academyinfo.go.kr/pubinfo/pubinfo0360/selectListLink.do (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Etikan, I.; Bala, K. Sampling and sampling methods. Biomet. Biostat. Int. J. 2017, 5, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.A.; Gullone, E. Why we should not use 5-point Likert scales: The case for subjective quality of life measurement. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Quality of Life in Cities, Kent Ridge, Singapore, 8–10 March 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, D.R.; Gillespie, D.F. Phrase completion scales: A better measurement approach than Likert scales? J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2007, 33, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.O. A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2011, 37, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. Enhancing organizational survivability in a crisis: Perceived organizational crisis responsibility, stance, and strategy. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11532–11545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Colić, V. Journalists and public relations specialists: A coorientational analysis. Public Relation Rev. 2016, 42, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Verčič, D.; Laco, K. Co-Orientation between Publics in Two Countries: A Decade Later. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 1624–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter, J.F.C.; Dodou, D. Five-Point Likert Items: T test versus Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon. Pract. Assess Res. Eval. 2010, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Onsman, A.; Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Aust. J. Paramed. 2010, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOSTINNO. Available online: https://www.americaninno.com/boston/inno-news-boston/flywire-raises-120m-led-by-goldman-sachs-acquires-payments-startup/ (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Jiani, M.A. Why and how international students choose Mainland China as a higher education study abroad destination. High. Educ. 2017, 74, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wilkins, S. The effects of lecturer commitment on student perceptions of teaching quality and student satisfaction in Chinese higher education. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2015, 37, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busser, J.A.; Shulga, L.V. Involvement in consumer-generated advertising: Effects of organizational transparency and brand authenticity on loyalty and trust. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1763–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Pan, L.Y.; Hsu, C.H.; Lee, D.C. Exploring the Sustainability Correlation of Value Co-Creation and Customer Loyalty-A Case Study of Fitness Clubs. Sustainability 2018, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Author | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual definition and categorization of the issue | Foster [29] | 2002 | Pointing out the current problems that higher education institutions are facing |

| Wright [30] | 2010 | Interviewed Canadian presidents and vice presidents of universities’ perceptions on sustainable higher education institutions | |

| Figueiró; Figueiró [31] | 2015 | Reviewed the past 63 articles between 2003 and 2013 regarding sustainability of higher education | |

| Criticism and negation of higher education | McLennan [7] | 2009 | Argued that we need to rethink about the idea of the university in the contemporary world |

| Zepke. [8] | 2013 | Questioned the current teaching system of higher education, specifically focused on student engagement | |

| Governmental policies | Gribble [4] | 2008 | This study discusses about governmental policy issues of higher education institutions in underdeveloped countries, due to the crisis from the worldwide trend with international students’ mobility. |

| Haugen [5] | 2013 | Pointed out the problems of current China’s policy for recruitment of Sino-African students and suggested political implications for better educational environment | |

| Sá et al. [6] | 2018 | Proposed proper policies for governments using comparative analysis between 2000 and 2016 in Australia, Canada, England, and the USA | |

| Alternative education programs | Fien [11] | 2002 | Argued that higher education can maintain its sustainability by adopting eclectic approach to the choice of goals and research methodologies |

| Rusinko [13] | 2009 | Proposed a matrix for higher education institutions to choose a right strategy to maintain their sustainability | |

| Lozano et al. [12] | 2011 | Discussed about how universities can escape from traditional education system in order to maintain its sustainability | |

| O’Byrne et al. [15] | 2015 | Suggested the better curriculum design for higher education institutions by analyzing 27 bachelor’s and 27 master’s programs | |

| Ceulemans et al. [10] | 2015 | Analyzed the crucial factors for sustainable higher education intuitions | |

| Bandyopadhyay et al. [9] | 2015 | Studied factors influencing student participation in study abroad program | |

| Shin et al. [14]. | 2018 | How consumer’s perceived benefits and perceived risks affect the service evaluation process of converged services |

| Category | Author | Year | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service trade policy | Melvin [43] | 1989 | Compared the predictability of commodity and services and analyzed tariffs and welfares produced by commodities and services |

| Drake; Nicolaïdis [44] | 1992 | Discussed about whether services must be governed by traditional regulatory regimes or by the market-based rules in GATT | |

| Beverelli et al. [45] | 2017 | Demonstrated how the restrictions on service trade affect manufacturing productivity | |

| Service operation | Roth; Van Der Velde [46] | 1991 | Emphasizes to devise a service delivery system that is congruent with the desired service concept |

| Gummesson [47] | 1994 | Operational differences of product as a center and service as a layer around the product, and service as a center and product as a layer around the service | |

| Oliva; Kallenberg [48] | 2003 | Defined how service strategy must be applied differently depending on if it is core service with manufacturing good | |

| Alam [49] | 2006 | Categorized services as how new and innovative the service is and empirically analyzed the best kind of new service. As a result, Alam indicated that the best option for the service firms is not the most innovated service, but the one with a low cost and less risky option | |

| Lightfoot; Gebauer [50] | 2011 | How customized or standardized the type of services must be depending on the number of customers | |

| Service consumer behavior | Liang et al. [51] | 2013 | Identified the relationship between service quality and customer’s switching behavior |

| Ho [52] | 2014 | Examined relationship between consumer participation and consumer evaluation of the brand | |

| Rather et al. [53] | 2018 | Analyzed the interrelationships between the consumer engagement and higher order marketing constructs |

| Factor | COST | EDUC | HOSP | FNFR | LCTN | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | LCT | DCT | SCF | AST | TPO | IRP | DVM | DPM | IQT | FRD | HPI | GDF | HIM | JOB | LAD | BCT | SRT |

| He et al. [55] | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| de Jong et al. [56] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| Duarte et al. [57] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Lindgren-Gatfield and Hyde [58] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| María Cubillo et al. [59] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Maringe [60] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Mazzarol [61] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| Moogan et al. [62] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Navrátilová [63] | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Price et al. [64] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| Russel [65] | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Shanka et al. [66] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| Soutar and Turner [67] | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||

| Telli Yamamoto [68] | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Yang [69] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||

| University Staff/N(%) = 120(100) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Place of employment | Academic department offices | 28% |

| Department of administration, PR, and admissions | 22% | |

| Department of international affairs | 50% | |

| Position | Staff (including office assistants) | 66% |

| Team leader | 18% | |

| School executive | 2% | |

| Professor | 12% | |

| Etc. | 2% | |

| International Students/N(%) = 262(100) | ||

| Gender | Male | 25.5% |

| Female | 75.5% | |

| Marital status | Unmarried | 100% |

| Married | 0% | |

| Residence period in Korea | Within 6 months | 10% |

| 7 months~1 year | 12% | |

| 1 year and 1 month to ~2 years | 22% | |

| 2 years and 1 month to ~4 years | 42% | |

| More than 4 year and 1 month | 14% | |

| Income level of financial supporter | High | 1% |

| Mid-upper | 21% | |

| Medium | 71% | |

| Middle-low | 5% | |

| Low | 3% | |

| Group | Survey Criteria | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COST | 1. Reasonableness of local living costs | LCT | e.g., Moogan et al. [62] |

| 2. Reasonableness of accommodation cost (dormitory) | DCT | e.g., María Cubillo et al. [59] | |

| 3. Opportunity of scholarships for international students | SCF | e.g., Shanka et al. [66] | |

| 4. Reasonableness of university tuition | AST | e.g., He et al. [55] | |

| 5. Variety of tuition payment options | TPO | e.g., Maringe [60] | |

| EDUC | 1. Institutional reputation | IRP | e.g., Shin et al. [14] |

| 2. Diversity of majors | DVM | e.g., Lindgren-Gatfield and Hyde [58] | |

| 3. Variety of extracurricular programs for international students | DPM | e.g., de Jong et al. [56] | |

| 4. Instructional quality | IQT | e.g., Shin et al. [14] | |

| HOSP | 1. Pre-existing acquaintances at the target university | FRD | e.g., Moogan et al. [62] |

| 2. High ratio of international students | HPI | e.g., Mazzarol [61] | |

| 3. Appropriateness of accommodation (dormitory) | GDF | e.g., Shin et al. [14] | |

| FNFR | 1. High possibility of future immigration to host country | HIM | e.g., Yang [69] |

| 2. High of possibility for employment in host country after graduation | JOB | e.g., Soutar and Turner [67] | |

| 3. Exposure to local (at home country) advertisements of the university | LAD | e.g., Telli Yamamoto [68] | |

| LCTN | 1. University’s proximity to metro-area | BCT | e.g., Price et al. [64] |

| 2. National security level | SRT | e.g., Duarte et al. [57] | |

| Co-Orientation Method | Code | Current Study |

|---|---|---|

| Individual A | A | University staff |

| Individual B | B | International student |

| Object X | X | Study abroad program |

| A’s perception of X | Aa | University staffs’ perception of the study abroad program they offer |

| B’s perception of X | Bb | International students’ perception of the study abroad program they are enrolled in. |

| A’s estimate of Bb | Ab | University staffs’ estimate of international students’ perception of the study abroad program |

| B’s estimate of Aa | Ba | International students’ estimate of university staffs’ perception of the study abroad program |

| Abbreviation | COST | EDUC | HOSP | FNFR | LCTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCT | 0.765 | 0.306 | 0.174 | 0.161 | −0.080 |

| DCT | 0.763 | 0.149 | 0.370 | 0.044 | −0.005 |

| SCF | 0.716 | 0.062 | −0.067 | 0.040 | 0.337 |

| AST | 0.715 | 0.133 | −0.068 | 0.063 | 0.362 |

| TPO | 0.632 | 0.462 | 0.154 | 0.050 | −0.087 |

| IQT | 0.132 | 0.823 | 0.061 | 0.135 | 0.070 |

| DVM | 0.204 | 0.699 | 0.093 | −0.068 | 0.091 |

| DPM | 0.125 | 0.678 | 0.181 | −0.054 | −0.164 |

| IRP | 0.161 | 0.667 | −0.125 | 0.172 | 0.299 |

| FRD | 0.099 | 0.115 | 0.813 | −0.012 | 0.072 |

| HPI | 0.026 | −0.140 | 0.685 | 0.282 | 0.030 |

| GDF | 0.124 | 0.214 | 0.685 | −0.019 | 0.049 |

| HIM | 0.044 | 0.014 | 0.072 | 0.843 | −0.043 |

| JOB | 0.023 | −0.008 | −0.092 | 0.796 | 0.233 |

| LAD | 0.162 | 0.135 | 0.245 | 0.583 | −0.018 |

| BCT | 0.123 | 0.008 | 0.173 | 0.091 | 0.871 |

| SRT | 0.242 | 0.501 | 0.020 | 0.052 | 0.557 |

| COST | EDUC | FNFR | HOSP | LCTN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST | 0.812 | 0.236 | 0.138 | 0.001 | 0.230 |

| DCT | 0.793 | 0.109 | 0.080 | 0.250 | 0.190 |

| SCF | 0.760 | −0.016 | 0.180 | 0.084 | 0.313 |

| LCT | 0.720 | 0.185 | 0.318 | 0.304 | −0.067 |

| TPO | 0.711 | 0.267 | 0.281 | 0.237 | −0.099 |

| IQT | 0.124 | 0.887 | 0.139 | 0.023 | 0.153 |

| IRP | 0.171 | 0.826 | 0.091 | 0.025 | 0.223 |

| DVM | 0.147 | 0.783 | 0.093 | 0.311 | 0.029 |

| DPM | 0.100 | 0.498 | 0.278 | 0.471 | −0.184 |

| JOB | 0.168 | 0.110 | 0.832 | −0.014 | 0.153 |

| HIM | 0.258 | 0.163 | 0.757 | 0.195 | −0.044 |

| LAD | 0.187 | 0.104 | 0.717 | 0.310 | 0.171 |

| HPI | 0.059 | −0.049 | 0.303 | 0.756 | 0.222 |

| GDF | 0.337 | 0.236 | 0.014 | 0.741 | 0.099 |

| FRD | 0.333 | 0.347 | 0.139 | 0.587 | 0.186 |

| BCT | 0.279 | 0.242 | 0.215 | 0.222 | 0.751 |

| SRT | 0.336 | 0.487 | 0.076 | 0.309 | 0.565 |

| COSTa | EDUCa | HOSPa | FNFRa | LCTNa | COSTb | EDUCb | HOSPb | FNFRb | LCTNb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSTa | 0.57 | |||||||||

| EDUCa | 0.36 (0.13) ** | 0.50 | ||||||||

| HOSPa | 0.40 (0.16) ** | 0.17 (0.03) | 0.60 | |||||||

| FNFRa | 0.40 (0.16) ** | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.48 (0.23) ** | 0.46 | ||||||

| LCTNa | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.34 (0.12) ** | 0.034 (0.00) | 0.21 | |||||

| COSTb | 0.26 (0.07) * | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.21 (0.05) | 00.08 (0.01) | 00.08 (0.01) | 0.61 | ||||

| EDUCb | −0.02 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.00) | 0.11 (0.01) | 00.16 (0.03) | −0.19 (0.04) | 0.46 (0.21) ** | 0.52 | |||

| HOSPb | −0.06 (0.00) | −0.22 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.00) | 0.35 (0.12) ** | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.30 (0.09) ** | 0.28 (0.08) ** | 0.58 | ||

| FNFRb | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.17 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.00) | 0.12 (0.01) | −0.12 (0.15) | 0.20 (0.04) * | 0.21 (0.04) * | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.63 | |

| LCTNb | 0.04 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.20 (0.04) | 0.32 (0.10) * | −0.18 (0.03) | 0.49 (0.24) ** | 0.48 (0.23) ** | 00.14 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.07) ** | 0.88 |

| COSTa | EDUCa | HOSPa | FNFRa | LCTNa | COSTb | EDUCb | HOSPb | FNFRb | LCTNb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSTa | 0.55 | |||||||||

| EDUCa | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.56 | ||||||||

| HOSPa | 0.24 (0.06) | 0.37 (0.14) ** | 0.64 | |||||||

| FNFRa | 0.51 (0.26) ** | 0.30 (0.09) * | 0.34 (0.11) ** | 0.67 | ||||||

| LCTNa | 0.35 (0.12) ** | 0.57 (0.32) ** | 0.23 (0.05) | 0.28 (0.08) * | 0.84 | |||||

| COSTb | 0.16 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.00) | −0.06 (0.00) | −0.04 (0.00) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.75 | ||||

| EDUCb | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.06 (0.00) | −0.02 (0.00) | −0.04 (0.00) | −0.16 (0.02) | 0.45 (0.20) ** | 0.68 | |||

| HOSPb | 0.04 (0.00) | −0.18 (0.03) | −0.08 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.00) | −0.11 (0.01) | 0.66 (0.44) ** | 0.56 (0.31) ** | 0.70 | ||

| FNFRb | 0.20 (0.04) | −0.00 (0.00) | 0.03 (0.00) | 0.16 (0.03) | −0.04 (0.00) | 0.49 (0.24) ** | 0.37 (0.14) ** | 0.52 (0.27) ** | 0.70 | |

| LCTNb | 0.07 (0.00) | 0.04 (0.00) | −0.01 (0.00) | −0.04 (0.00) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.64 (0.41) ** | 0.53 (0.28) ** | 0.68 (0.47) ** | 0.44 (0.20) ** | 0.83 |

| The Order of Difference Magnitude | Factors |

|---|---|

| 1st | Instructional quality (IQT) |

| 2nd | Variety of tuition payment options (TPO) |

| 3rd | Variety of extracurricular programs for international students (DPM) |

| 4th | Diversity of majors (DVM) |

| 5th | Reasonableness of local living costs (LCT) |

| 6th | National security level (SRT) |

| 7th | Institutional reputation (IRP) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, E.; Shin, M.M. Study Abroad in Support of Higher Education Sustainability: An Application of Service Trade Strategies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062556

Oh E, Shin MM. Study Abroad in Support of Higher Education Sustainability: An Application of Service Trade Strategies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062556

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Eunji, and M. Minsuk Shin. 2020. "Study Abroad in Support of Higher Education Sustainability: An Application of Service Trade Strategies" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062556

APA StyleOh, E., & Shin, M. M. (2020). Study Abroad in Support of Higher Education Sustainability: An Application of Service Trade Strategies. Sustainability, 12(6), 2556. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062556