Doing More on the Corporate Sustainability Front: A Longitudinal Analysis of CSR Reporting of Global Fashion Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. CSR Challenges in the Fashion Industry

2.2. CSR Related to Environmental Issues

2.3. CSR Related to Labor Issues

2.4. CSR Reporting in the Fashion Industry

2.5. Purpose of Study and Research Questions

- RQ1a.

- What are the themes and subthemes of CSR practices communicated in the sustainability reports of global fashion companies?

- RQ1b.

- Are there any changes in CSR communication over time?

- RQ2a.

- What are the key labor issues communicated in the sustainability reports of global fashion companies?

- RQ2b.

- Are there any changes in the practices over time?

- RQ3a.

- What are the key environmental issues communicated in the sustainability reports of global fashion companies?

- RQ3b.

- Are there any changes in the practices over time?

- RQ4.

- Does the CSR reporting of fashion companies place more emphasis on labor issues than environmental issues?

3. Materials and Methods

Firm Selection

4. Data Collection

5. Research Method

6. Statistical Analyses

7. Findings

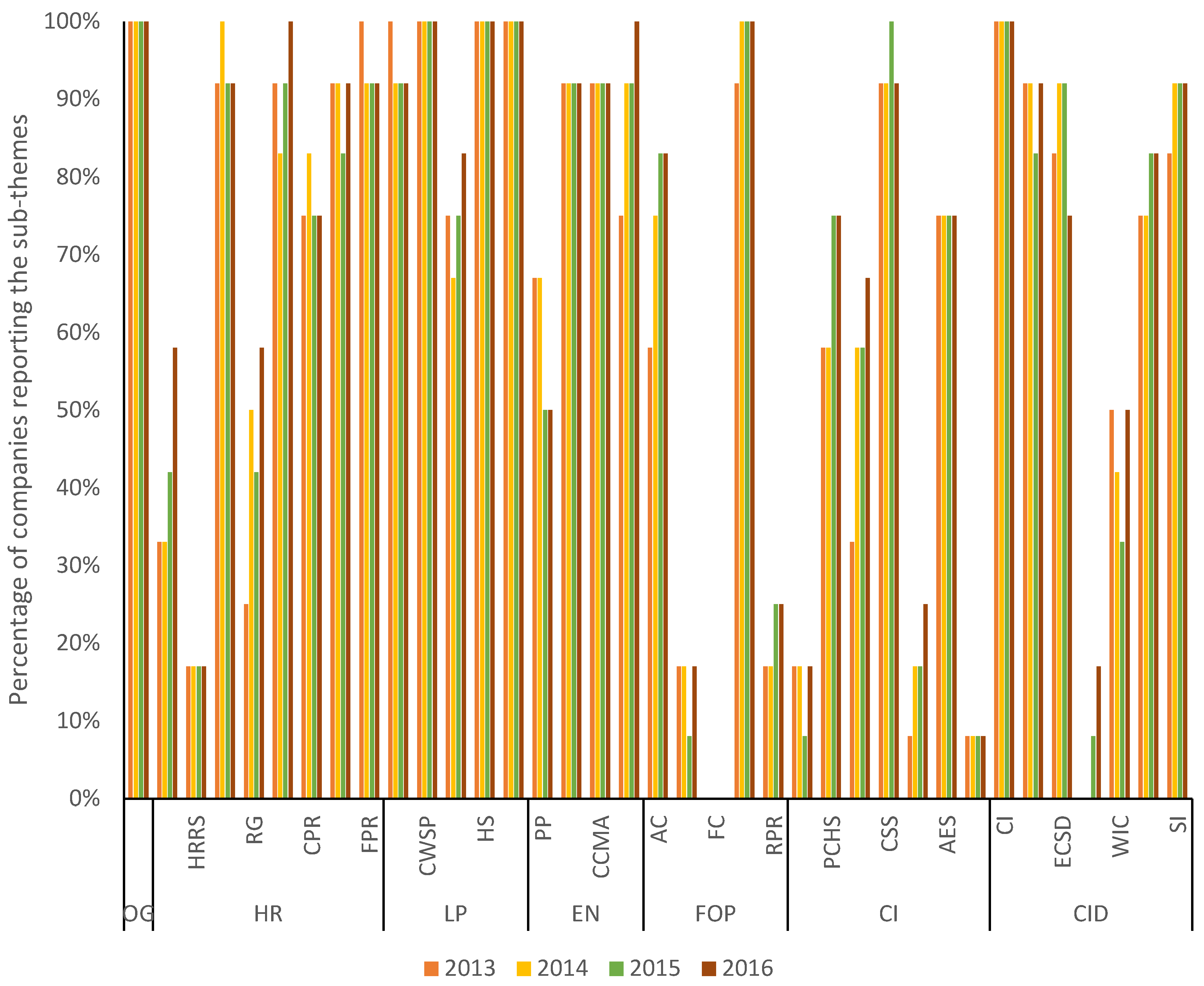

7.1. Comprehensive Reporting of All CSR Themes

7.2. Salient Growth in Reporting on Human Rights and Consumer Issues

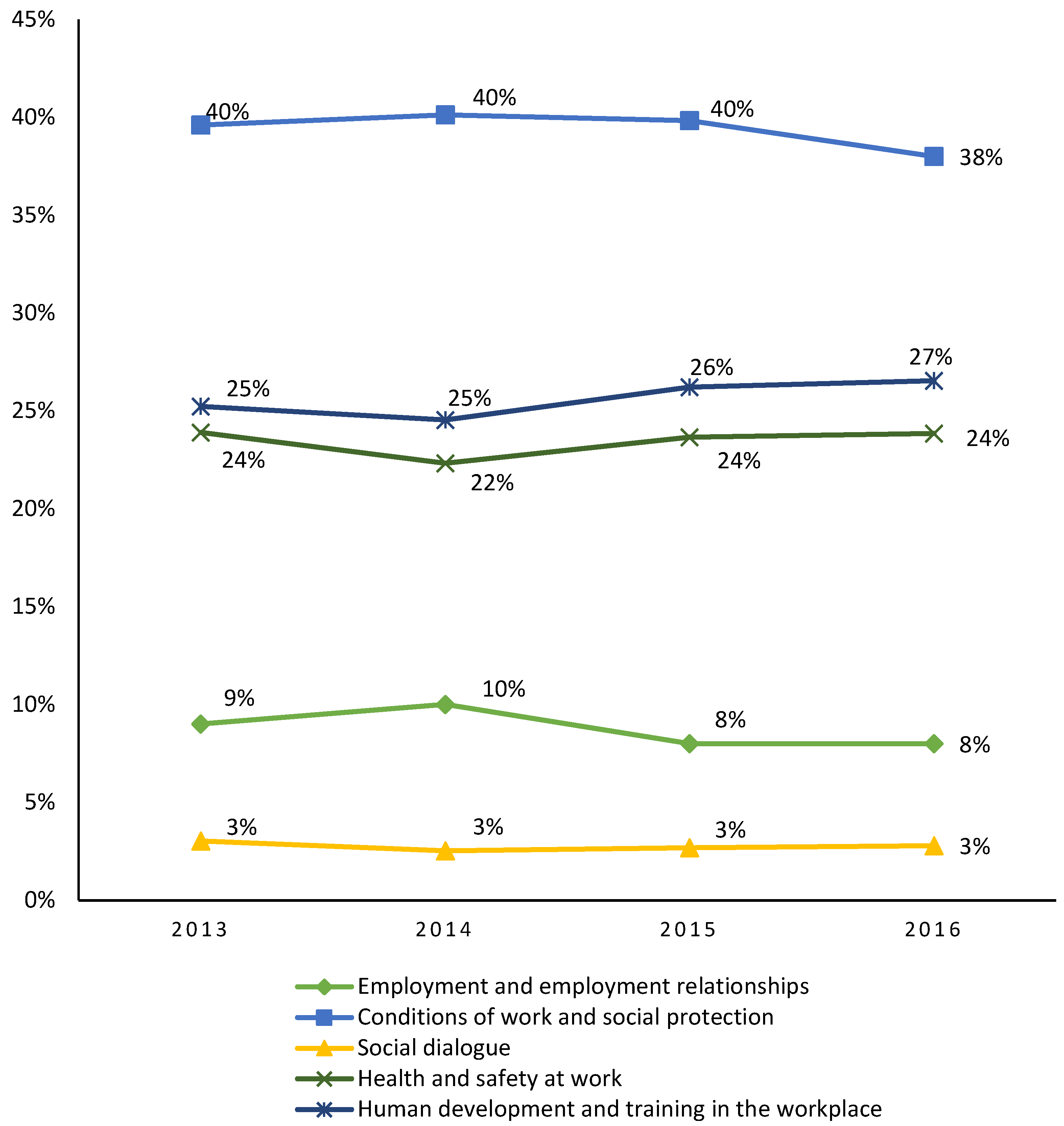

7.3. Reporting of Labor Practices in the Fashion Industry

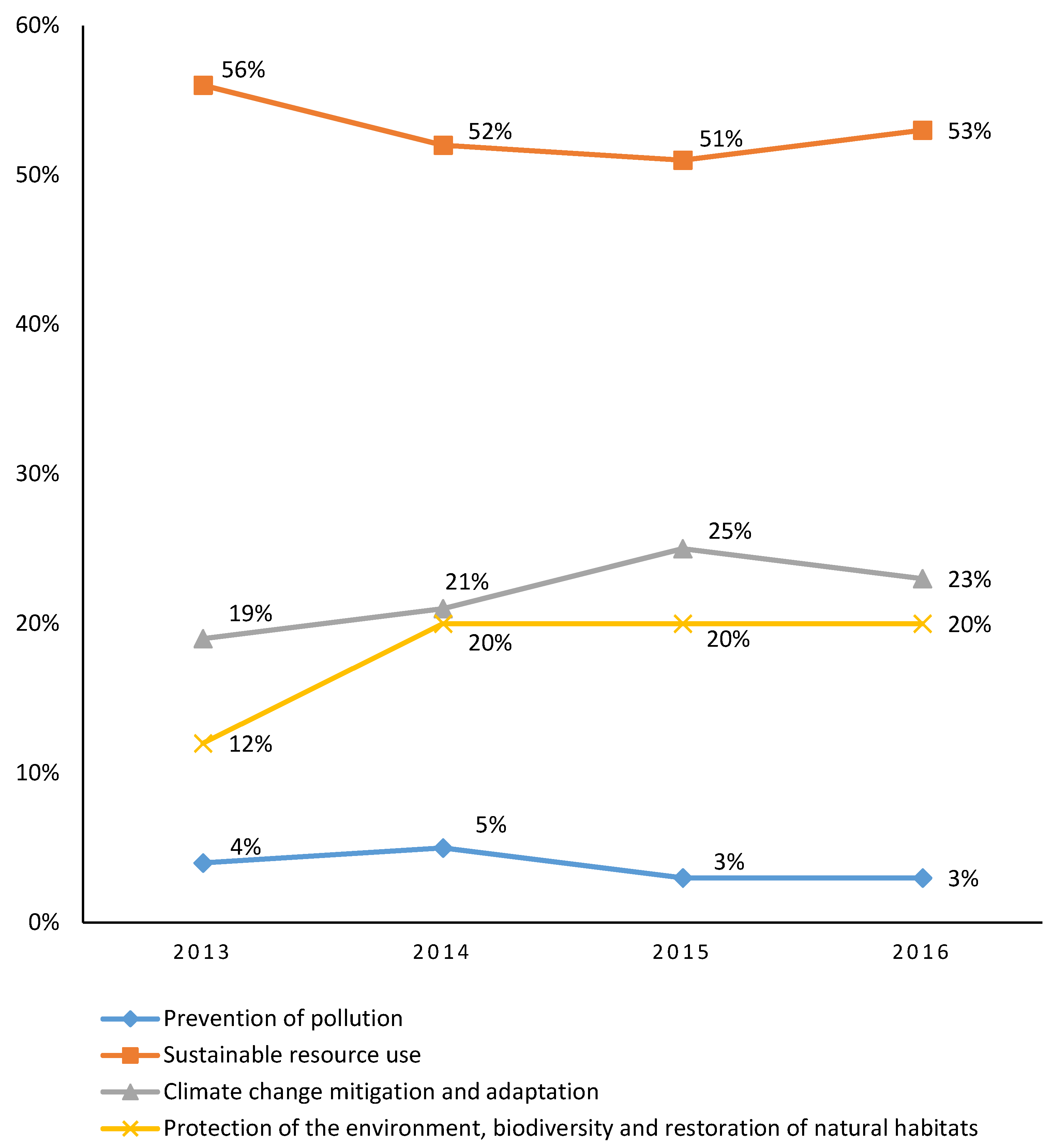

7.4. Key Issues of Environmental Practices Communicated in the Fashion Industry

8. Discussion and Conclusions

8.1. Salient Growth in Reporting on Human Rights

8.2. Greater Emphasis on Human Development and Training in the Workplace

8.3. Focus on Environmental Practices Has Shifted from Prevention of Pollution to Promotion of Sustainable Deeds

9. Implications, Further Studies and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weidstam, E. Sustainability Passion in Fashion: Challenges and Opportunities for Small and Medium-Sized Swedish Apparel Brands when Working with Corporate Social Responsibility in their Global Supply Chain. Available online: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy.lb.polyu.edu.hk/document/5997938/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Perry, P. Exploring the influence of national cultural context on CSR implementation. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, P.; Towers, N. Conceptual framework development. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 478–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-L.; Burns, L.D. Environmental Analysis of Textile Products. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.; Bardecki, M.; Searcy, C. Environmental Impacts in the Fashion Industry: A Life-cycle and Stakeholder Framework. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2012, 45, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys, 2nd ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ansett, S. Mind the Gap: A journey to sustainable supply chains. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2007, 19, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economist, T. Bursting at the seams—Bangladesh’s Clothing Industry. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2013/05/04/disaster-at-rana-plaza (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Paulina, K. The CSR Challenges in the Clothing Industry. J. Corp. Responsib. Leadersh. 2016, 3, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basil, D.Z.; Erlandson, J. Corporate Social Responsibility website representations: A longitudinal study of internal and external self-presentations. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podnar, K. Communicating corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giau, A.D. Sustainability practices and web-based communication an analysis of the Italian fashion industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Marrewijk, M. Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B. Defining CSR: Problems and Solutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-century Business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and Corporate Sustainability: What is the difference and does it matter? 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3549577 (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Christopher, M.; Lowson, R.; Peck, H. Creating agile supply chains in the fashion industry. International J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2004, 32, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, P.; Towers, N. Determining the antecedents for a strategy of corporate social responsibility by small- and medium-sized enterprises in the UK fashion apparel industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C. Corporate social sustainability in supply chains: A thematic analysis of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, G.; Moore, C.M. Fashion clothing—Where does it all end up? Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, M.A.; Eckman, M. Social Responsibility: The Concept as Defined by Apparel and Textile Scholars. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, N.F. Challenging the Status Quo. Available online: http://nordicfashionassociation.com/news/challenging-staus-quo/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Crippa, L.; Moretto, A. Environmental sustainability in fashion supply chains: An exploratory case based research. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Altuntas, C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.L.; De Silva, I.; Hartmann, S. An investigation into the financial return on corporate social responsibility in the apparel industry. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2012, 45, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, E.; Linke, M.; Tobler, M.; Beke, B.V. EU COST Action 628: Life cycle assessment (LCA) of textile products, eco-efficiency and definition of best available technology (BAT) of textile processing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudal, T. An Attempt to Determine the CSR Potential of the International Clothing Business. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, J.; Hartlin, B.; Perumalpillai, S.; Selby, S.; Aumônier, S. Mapping of evidence on sustainable development impacts that occur in life cycles of clothing. In A Report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; Environmental Resources Management (ERM) Ltd.: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ruwanpura, K. Ethical Codes: Reality and Rhetoric—A Study of Sri Lanka’s Apparel Sector. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/337113/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Dirnbach, E. Weaving a Stronger Fabric: Organizing a global sweat-free apparel production agreement. Work. USA 2008, 11, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearson, M. Cashing in: GIANT Retailers, Purchasing Practices, and Working Conditions in the Garment Industry, Clean Clothes Campaign. Available online: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com.hk/&httpsredir=1&article=1418&context=globaldocs (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Sheehy, B. TNC Code of Conduct or CSR? A Regulatory Systems Perspective. In Code of Conduct on Transnational Corporations. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Rahim, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. Supply Chain Specific? Understanding the Patchy Success of Ethical Sourcing Initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A company-level measurement approach for CSR. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildt, S. CSR Communication: A Promotional Tool or a Portrayal of the Reality? An Explorative Study in the Apparel and Footwear Industry. Master’s Thesis, University of Boras, Borås, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, M.; Perry, M. Walking the talk? Environmental responsibility from the perspective of small-business owners. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcikova, K.; Stefanikova, Ľ.; Rypakova, M. CSR Reporting as an Important Tool of CSR Communication. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woo, H.; Jin, B. Apparel firms’ corporate social responsibility communications. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.; Byun, S.-E.; Kim, H.; Hoggle, K. Assessment of Leading Apparel Specialty Retailers’ CSR Practices as Communicated on Corporate Websites: Problems and Opportunities. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, I. The use of economic, social and environmental indicators as a measure of sustainable development in Spain. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, L.C.; Searcy, C. An analysis of indicators disclosed in corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Li, H. Corporate social responsibility communication of Chinese and global corporations in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2009, 35, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Lee, Y.; Wu, C.; Lo, K. A Comparison Study on the Evaluation Criteria for Corporate Social Responsibility. Available online: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy.lb.polyu.edu.hk/document/5997938/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- ISO 26000 Social Responsibility. Available online: https://www.iso.org/iso-26000-social-responsibility.html (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- UN Global Compact. Corporate Responsibility Report 2009. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/participation/report/cop/create-and-submit/detail/6381 (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Mazars. Business and Human Rights. Available online: https://www.mazars.co.uk/Home/Services/Consulting/People-Processes/Business-and-Human-Rights (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- UNGP Reporting Framework Website. About Us. Available online: https://www.ungpreporting.org/about-us/ (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Bolton, S.; Kim, R.; O’Gorman, K. Corporate social responsibility as a dynamic internal organizational process: A case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, P.; Mani, S. Learning and earning: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in India. Labour Econ. 2017, 45, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nanda, P.; Mishra, A.; Walia, S.; Sharma, S.; Weiss, E. Advancing Women, Changing Lives: An Evaluation of Gap Inc.’s P.A.C.E. Program. Available online: https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/PACE_Report_PRINT_singles_lo.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Skills, C. Employment and Productivity in the Garments and Construction Sectors in Bangladesh and Elsewhere. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5977616f40f0b649a7000022/Skills_productivity_and_employment.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Gaskill-Fox, J.; Hyllegard, K.H.; Ogle, J.P. CSR reporting on apparel companies’ websites: Framing good deeds and clarifying missteps. Fash. Text. 2014, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, A.K. Ethical corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the pharmaceutical industry: A happy couple. J. Med. Mark. 2009, 9, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Rob, H. Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamberti, L.; Lettieri, E. CSR practices and corporate strategy: Evidence from a longitudinal case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Company Name | Country of Origin | FY2015 Retail Revenue (Million USD) | Company Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| The TJX Companies, Inc. | America | 30,945 | A |

| LVMH Moet Hennessy | France | 25,605 | B |

| Inditex, S.A. | Spain | 23,074 | C |

| H&M Hennes & Mauritz AB | Sweden | 21,678 | D |

| The Gap, Inc. | America | 15,797 | E |

| Fast Retailing Co., Ltd. | Japan | 14,239 | F |

| Kering S.A. | France | 7039 | G |

| Next plc | The UK | 6339 | H |

| Hermes International SCA | France | 4310 | I |

| Ralph Lauren Corporation | America | 3933 | J |

| Coach, Inc. | America | 3760 | K |

| American Eagle Outfitters, Inc. | America | 3522 | L |

| Core Themes | Organizational Governance (OG) | Human Rights (HR) | Labor Practice (LP) | The Environment (EN) | Fair Operating Practices (FOP) | Consumer Issues (CI) | Community Involvement and Development (CID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-themes | N/A | Due diligence (DD) Human rights risk situations (HRRS) Avoidance of complicity (AoC) Discrimination and vulnerable groups (DVG) Civil and political rights (CPR) Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) Resolving grievances (RG) Fundamental principles and rights at work (FPR) | Employment and employment relationships (EER) Conditions of work and social protection (CWSP) Social dialogue (SD) Health and safety at work (HS) Human development and training in the workplace (HDT) | Prevention of pollution (PP) Sustainable resource use (SRU) Climate change mitigation and adaptation (CCMA) Protection of the environment, biodiversity and restoration of natural habitats (PEBNH) | Anti-corruption (AC) Responsible political involvement (RPI) Fair competition (FC) Promoting social responsibility in the value chain (PSR) Respect for property rights (RPR) | Fair marketing, factual and unbiased information and fair contractual practices (FMCP) Protecting consumers’ health and safety (PCHS) Sustainable consumption (SC) Consumer service, support, and complaint and dispute resolution (CSS) Consumer data protection and privacy (CDPP) Access to essential services (AES) Education and awareness (EA) | Community involvement (CI) Education and culture (EC) Employment creation and skills development (ECSD) Technology development and access (TDA) Wealth and income creation (WIC) Health (HE) Social investment (SI) |

| Variables | Percent of Agreement | Cohen’s Kappa | Krippendorff’s Alpha | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 of company E | 97.80% | 0.96 | 0.96 | 46 |

| 2015 of company E | 97.80% | 0.961 | 0.962 | 46 |

| 2014 of company E | 91.30% | 0.85 | 0.851 | 46 |

| 2013 of company E | 91.30% | 0.85 | 0.851 | 46 |

| 2016 of company F | 93.50% | 0.899 | 0.9 | 46 |

| 2015 of company F | 95.70% | 0.933 | 0.934 | 46 |

| 2014 of company F | 97.80% | 0.967 | 0.967 | 46 |

| 2013 of company F | 97.80% | 0.967 | 0.967 | 46 |

| Themes | Subthemes | 2013 (N/%) | 2014 (N/%) | 2015 (N/%) | 2016 (N/%) | M | SD | Average Annual Growth Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OG | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | |

| HR | DD | 4 | 33% | 4 | 33% | 5 | 42% | 7 | 58% | 42% | 12% | 22% |

| HRRS | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 17% | 0% | 0% | |

| AoC | 11 | 92% | 12 | 100% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 94% | 4% | 0% | |

| RG | 3 | 25% | 6 | 50% | 5 | 42% | 7 | 58% | 44% | 14% | 41% | |

| DVG | 11 | 92% | 10 | 83% | 11 | 92% | 12 | 100% | 92% | 7% | 3% | |

| CPR | 9 | 75% | 10 | 83% | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 77% | 4% | 0% | |

| ESCR | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 10 | 83% | 11 | 92% | 90% | 4% | 0% | |

| FPR | 12 | 100% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 94% | 4% | −3% | |

| LP | EER | 12 | 100% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 94% | 4% | −3% |

| CWSP | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | |

| SD | 9 | 75% | 8 | 67% | 9 | 75% | 10 | 83% | 75% | 7% | 4% | |

| HS | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | |

| HDT | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% | |

| EN | PP | 8 | 67% | 8 | 67% | 6 | 50% | 6 | 50% | 58% | 10% | −8% |

| SRU | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 92% | 0% | 0% | |

| CCMA | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 92% | 0% | 0% | |

| PEBNH | 9 | 75% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 12 | 100% | 90% | 10% | 10% | |

| FOP | AC | 7 | 58% | 9 | 75% | 10 | 83% | 10 | 83% | 75% | 12% | 13% |

| PRI | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 1 | 8% | 2 | 17% | 15% | 4% | 0% | |

| FC | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| PSR | 11 | 92% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 98% | 4% | 3% | |

| RPR | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 3 | 25% | 3 | 25% | 21% | 4% | 17% | |

| CI | FMCP | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 1 | 8% | 2 | 17% | 15% | 4% | 17% |

| PCHS | 7 | 58% | 7 | 58% | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 62% | 10% | 10% | |

| SC | 4 | 33% | 7 | 58% | 7 | 58% | 8 | 67% | 54% | 14% | 30% | |

| CSS | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 94% | 4% | 0% | |

| CDPP | 1 | 8% | 2 | 17% | 2 | 17% | 3 | 25% | 17% | 7% | 50% | |

| AES | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 75% | 0% | 0% | |

| EA | 1 | 8% | 1 | 8% | 1 | 8% | 1 | 8% | 8% | 0% | 0% | |

| CID | CIV | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 12 | 100% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| EC | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 10 | 83% | 11 | 92% | 90% | 4% | 0% | |

| ECSD | 10 | 83% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 9 | 75% | 85% | 8% | −3% | |

| TDA | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% | 2 | 17% | 6% | 8% | 33% | |

| WIC | 6 | 50% | 5 | 42% | 4 | 33% | 6 | 50% | 44% | % | 4% | |

| HE | 9 | 75% | 9 | 75% | 10 | 83% | 10 | 83% | 79% | 5% | 4% | |

| SI | 10 | 83% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 11 | 92% | 90% | 4% | 3% | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, P.; Ngai, C.S.-b. Doing More on the Corporate Sustainability Front: A Longitudinal Analysis of CSR Reporting of Global Fashion Companies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062477

Feng P, Ngai CS-b. Doing More on the Corporate Sustainability Front: A Longitudinal Analysis of CSR Reporting of Global Fashion Companies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062477

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Penglan, and Cindy Sing-bik Ngai. 2020. "Doing More on the Corporate Sustainability Front: A Longitudinal Analysis of CSR Reporting of Global Fashion Companies" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062477