Psychological Capital Protects Social Workers from Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress

Abstract

:1. Introduction: Occupational Risks Associated with the Social Work Profession

1.1. Burnout

1.2. Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS)

1.3. Theoretical Frameworks Used in the Current Study

1.4. PsyCap as a Personal Resource Against Burnout and STS

1.5. The Results of Previous Studies on the Interplay between PsyCap, Burnout and STS

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives of the Current Study

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

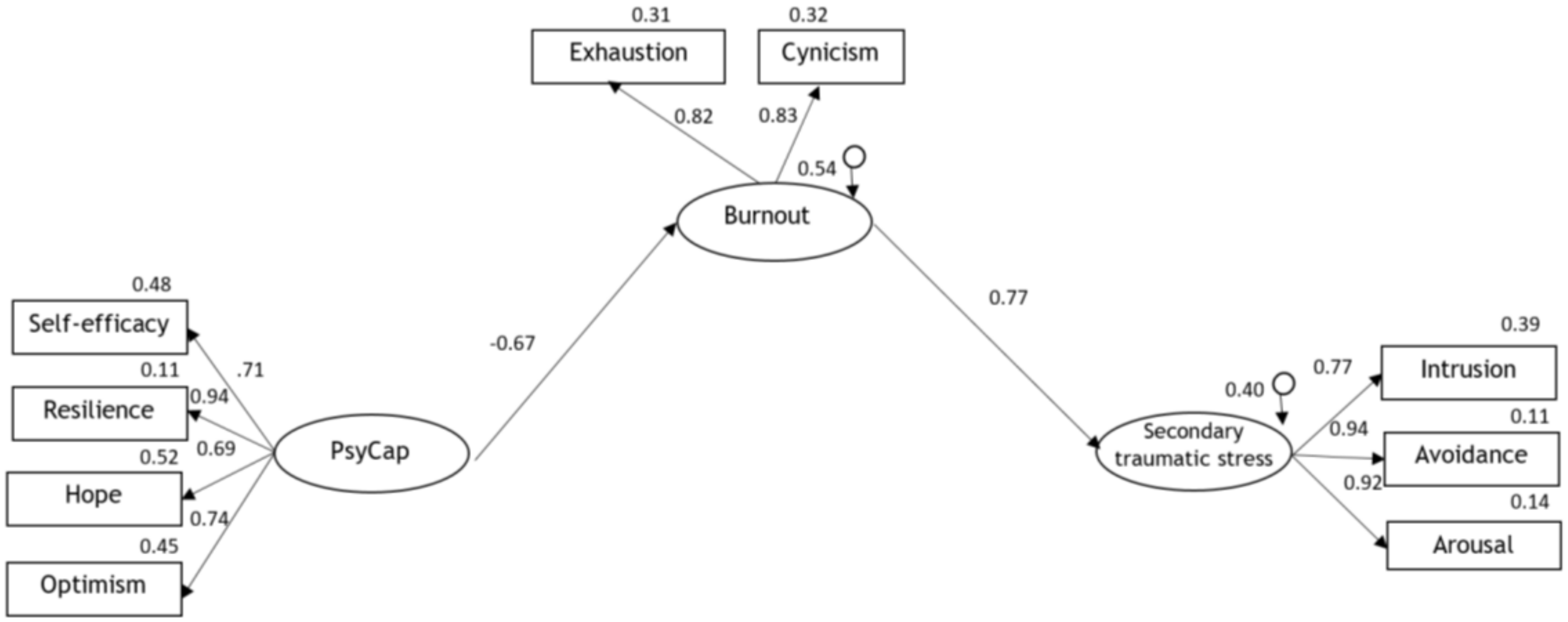

3.2. Measurement and Structural Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Social Work Practice

4.2. Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lloyd, C.; King, R.; Chenoweth, L. Social work, stress and burnout: A review. J. Ment. Health 2002, 11, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Schaufeli, W. Measuring burnout. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well Being; Cartwright, S., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder; Figley, C.R., Ed.; Brunner/Mazel: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bride, B.E. Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, K.; Lesnierowska, M.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Bock, J.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C.; Cieslak, R. What comes first, job burnout or secondary traumatic stress? Findings from two longitudinal studies from the US and Poland. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N. Fighting fire: Emotional risk management at social service agencies. Soc. Work 2015, 60, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Ji, J.; Kao, D. Burnout and physical health among social workers: A three-year longitudinal study. Soc. Work 2011, 56, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, P.; Campbell, A.; Taylor, B. Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. Br. J. Soc. Work 2015, 45, 1546–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wagaman, M.A.; Geiger, J.M.; Shockley, C.; Segal, E.A. The role of empathy in burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Soc. Work 2015, 60, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart. Work Stress 2005, 19, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M. Efficacy or inefficacy, that’s the question: Burnout and work engagement, and their relationships with efficacy beliefs. Anxiety Stress Coping 2007, 20, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vîrgă, D.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Beek, I.; Sulea, C. Attachment styles and employee performance: The mediating role of burnout. J. Psychol. 2019, 153, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyas, J.; Wind, L.H.; Kang, S.Y. Exploring the relationship between employment-based social capital, job stress, burnout, and intent to leave among child protection workers: An age-based path analysis model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B. Historical and conceptual development of burnout. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies; Perrewe, P.L., Ganste, D.C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, J.H.; Schneider, K.T.; Jenkins-Henkelman, T.M.; Moyle, L.L. Emotional social support and job burnout among high-school teachers: Is it all due to dispositional affectivity? J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Campos, E.; Vargas-Román, K.; Velando-Soriano, A.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Cañadas-de la Fuente, G.A.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Compassion Fatigue, Compassion Satisfaction, and Burnout in Oncology Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobson, J.M.; Rothschild, A.; Mirza, F.; Shapiro, M. Risk for burnout and compassion fatigue and potential for compassion satisfaction among clergy: Implications for social work and religious organizations. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2013, 39, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, D.; Kellar-Guenther, Y. Compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction among Colorado child protection workers. Child Abus. Negl. 2006, 30, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M. Factors influencing child welfare employee’s turnover: Focusing on organizational culture and climate. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2010, 32, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.B.; Matto, H.C.; Harrington, D. The Traumatic Stress Institute Belief Scale as a measure of vicarious trauma in a national sample of clinical social workers. Fam. Soc. 2001, 82, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, J.M.; MacNeil, G.A. Professional burnout, vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. Best Pract. Ment. Health 2010, 6, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cieslak, R.; Shoji, K.; Douglas, A.; Melville, E.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Robinson, M.M.; Yegidis, B.; Figley, C.R. Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2004, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Euwema, M.C. Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, J.; Ouweneel, A.; Le Blanc, P. Psychologische energiebronnen voor bevlogen werknemers: Psychologisch kapitaal in het job demands-resources model. Gedrag Organ. 2011, 24, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Lens, W. Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work Stress 2008, 22, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Freedy, J. Conservation of resources: A general stress theory applied to burnout. In Professional Burnout; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Swoboda, H.; Sibitz, I.; Frühwald, S.; Klug, G.; Bauer, B.; Priebe, S. Job satisfaction and burnout in professionals in Austrian mental health services. Psychiatr. Prax. 2005, 32, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porat, A.; Itzhaky, H. Burnout among trauma social workers: The contribution of personal and environmental resources. J. Soc. Work 2015, 15, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, A.; Aiello, A.; Giannetti, E. The work-related well-being of social workers: Framing job demands, psychological well-being, and work engagement. J. Soc. Work 2018, 19, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Molero Jurado, M.M.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Analysis of the Risk and Protective Roles of Work-Related and Individual Variables in Burnout Syndrome in Nurses. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Smith, R.M.; Palmer, N.F. Impact of positive psychological capital on employee well-being over time. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Newman, A.; Ucbasaran, D.; Zhu, F.E.I.; Hirst, G. Psychological capital: A review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, S120–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior: Developing and managing psychological strengths. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C. Psychological Capital: An Evidence-Based Positive Approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M.; Avolio, B.J. Psychological Capital: Developing the Human Competitive Edge; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. Human, social, and now positive psychological capital management: Investing in people for competitive advantage. Organ. Dyn. 2004, 33, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R. (Ed.) Handbook of Hope: Theory, Measures, and Applications; Academic Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Nosko, A. Exposure to workplace bullying and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomology: The role of protective psychological resources. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. The hopeful optimist. Psychol. Inq. 2002, 13, 288–290. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, B.C.; Luthans, K.W.; Avey, J.B. Building the leaders of tomorrow: The development of academic psychological capital. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2014, 21, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupșa, D.; Vîrgă, D.; Maricuțoiu, L.P.; Rusu, A. Increasing Psychological Capital: A pre-registered meta-analysis of controlled interventions. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2019, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Jensen, S.M. Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Firtko, A.; Edenborough, M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 60, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the Job Demands-Resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferradás, M.M.; Freire, C.; García-Bértoa, A.; Núñez, J.C.; Rodríguez, S. Teacher Profiles of Psychological Capital and Their Relationship with Burnout. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Grau, A.L. The influence of personal dispositional factors and organizational resources on workplace violence, burnout, and health outcomes in new graduate nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Fida, R. New nurses burnout and workplace well-being: The influence of authentic leadership and psychological capital. Burn. Res. 2014, 1, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Grau, A.L.; Finegan, J.; Wilk, P. Predictors of new graduate nurses’ workplace well-being: Testing the job demands-resources model. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, F.; Aziz, S.; Wuensch, K. From workaholism to burnout: Psychological capital as a mediator. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2017, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, R.; Song, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, D. The impact of psychological capital on job burnout of Chinese nurses: The mediator role of organizational commitment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lupșa, D.; Vîrgă, D. Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ): Analysis of the Romanian adaptation and validation. Psihol. Resur. Um. Psychol. Hum. Resour. 2018, 16, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Riolli, L.T.; Peng, A.C.; Spain, E.S. Resilience to traumatic exposure among soldiers deployed in combat. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, S.; Taliaferro, D. Compassion fatigue and psychological capital in nurses working in acute care settings. Int. J. Hum. Caring 2015, 19, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finklestein, M.; Stein, E.; Greene, T.; Bronstein, I.; Solomon, Z. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Vicarious Trauma in Mental Health Professionals. Health Soc. Work 2015, 40, e26–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harker, R.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Klaassen, F.; King, S. Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work 2016, 54, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscarino, J.A.; Adams, R.E.; Figley, C.R. Secondary trauma issues for Psychiatrists: Identifying vicarious trauma and job burnout. Psychiatr. Times 2010, 27, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, G.P.; Doust, J.A.; Steele, M.C. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2013, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gil, S.; Weinberg, M. Coping strategies and internal resources of dispositional optimism and mastery as predictors of traumatic exposure and of PTSD symptoms: A prospective study. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2015, 7, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Pietrantoni, L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. J. Loss Trauma 2009, 14, 364–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, S.J.; Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhang, Z. Psychological capital and employee performance: A latent growth modeling approach. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout and work engagement among teachers. J. Sch. Psychol. 2006, 43, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey. Manual; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Green, D.E.; Walkey, F.H. A confirmation of the three-factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 48, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C. Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. The Truth about Burnout; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koeske, G.F.; Koeske, R.D. Construct validity of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: A critical review and reconceptualization. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1989, 25, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. Burnout in work organisations. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Cooper, C.L., Robertson, I.T., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Enzmann, D. The Burnout Companion to Study & Practice: A Critical Essay; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M.P. Burnout as a developmental process: Consideration of models. In Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research; Schaufeli, W.B., Maslach, C., Marek, T., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.T.; Ashforth, B.E. A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulea, C.; Van Beek, I.; Sârbescu, P.; Vîrgă, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. Engagement, boredom, and burnout among students: Basic need satisfaction matters more than personality traits. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015, 42, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kaniskan, B.; McCoach, D.B. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 2015, 44, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, J. Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor; Research Papers; Stanford University, Graduate School of Business: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010; Volume 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Patera, J.L. Experimental analysis of a web-based training intervention to develop positive psychological capital. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2008, 7, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Peterson, S. The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2010, 21, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luthans, F.; Youssef-Morgan, C.M.; Avolio, B. Psychological Capital and Beyond; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, C.M.; Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Norman, S.M.; Combs, G.M. Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 169 | 87.56 |

| Male | 24 | 12.44 |

| Highest educational level graduated | ||

| MA or higher | 118 | 61.14 |

| BA degree | 73 | 37.82 |

| Lower than BA | 2 | 1.04 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 120 | 62.20 |

| Never married | 41 | 21.20 |

| Other | 32 | 16.60 |

| Tenure in social work occupation (years) | ||

| 7 or less | 63 | 32.64 |

| 8–15 | 76 | 39.38 |

| More than 15 | 54 | 27.98 |

| Tenure in the current workplace (months) | ||

| 36 or less | 60 | 31.09 |

| 37–108 | 54 | 27.98 |

| More than 108 | 79 | 40.93 |

| Type of employer | ||

| Public institution | 171 | 88.60 |

| Non-governmental organization | 22 | 11.40 |

| Observed Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.06 | 0.83 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| 4.86 | 0.7 | 0.68 ** | 0.84 | |||||||

| 4.53 | 0.74 | 0.49 ** | 0.68 ** | 0.72 | ||||||

| 4.44 | 0.85 | 0.48 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.50 ** | 0.77 | |||||

| 11.43 | 7.30 | −0.36 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.53 ** | 0.87 | ||||

| 6.67 | 6.43 | −0.51 ** | −0.59 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.66 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.79 | |||

| 10.95 | 3.72 | −0.22 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.34 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.79 | ||

| 14.79 | 5.59 | −0.37 ** | −0.44 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.53 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.89 | |

| 11.24 | 4.26 | −0.37 ** | −0.44** | −0.36 ** | −0.53 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.88 |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | ∆χ2 | ∆df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement model | ||||||||

| M1—three factors model | 77.09 ** | 24 | 3.21 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 | ||

| M2—single-factor model | 339.67 ** | 27 | 12.58 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 262.57 | 2 |

| Structural model | ||||||||

| M3—hypothetical (partial mediation) model | 77.88 ** | 25 | 4.08 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.06 | ||

| M4—alternative (total mediation) model | 77.09 ** | 24 | 3.21 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.06 | 0.79 | 1 |

| Independent Variable | Mediator | Dependent Variable | Estimate | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PsyCap | Burnout | Secondary traumatic stress | −0.53 ** | {−0.62, −0.44} |

| Intrusion | −0.41 ** | {−0.48, −0.33} | ||

| Avoidance | −0.50 ** | {−0.59, −0.41} | ||

| Arousal | −0.49 ** | {−0.57, −0.40} |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vîrgă, D.; Baciu, E.-L.; Lazăr, T.-A.; Lupșa, D. Psychological Capital Protects Social Workers from Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062246

Vîrgă D, Baciu E-L, Lazăr T-A, Lupșa D. Psychological Capital Protects Social Workers from Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062246

Chicago/Turabian StyleVîrgă, Delia, Elena-Loreni Baciu, Theofild-Andrei Lazăr, and Daria Lupșa. 2020. "Psychological Capital Protects Social Workers from Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062246

APA StyleVîrgă, D., Baciu, E.-L., Lazăr, T.-A., & Lupșa, D. (2020). Psychological Capital Protects Social Workers from Burnout and Secondary Traumatic Stress. Sustainability, 12(6), 2246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062246