Water as a Tourist Resource in Extremadura: Assessment of Its Attraction Capacity and Approximation to the Tourist Profile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case under Study

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods of Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tourism of Inland Waters and Its Relation with Other Tourism Types

3.2. The Profile of the Tourist of Inland Waters

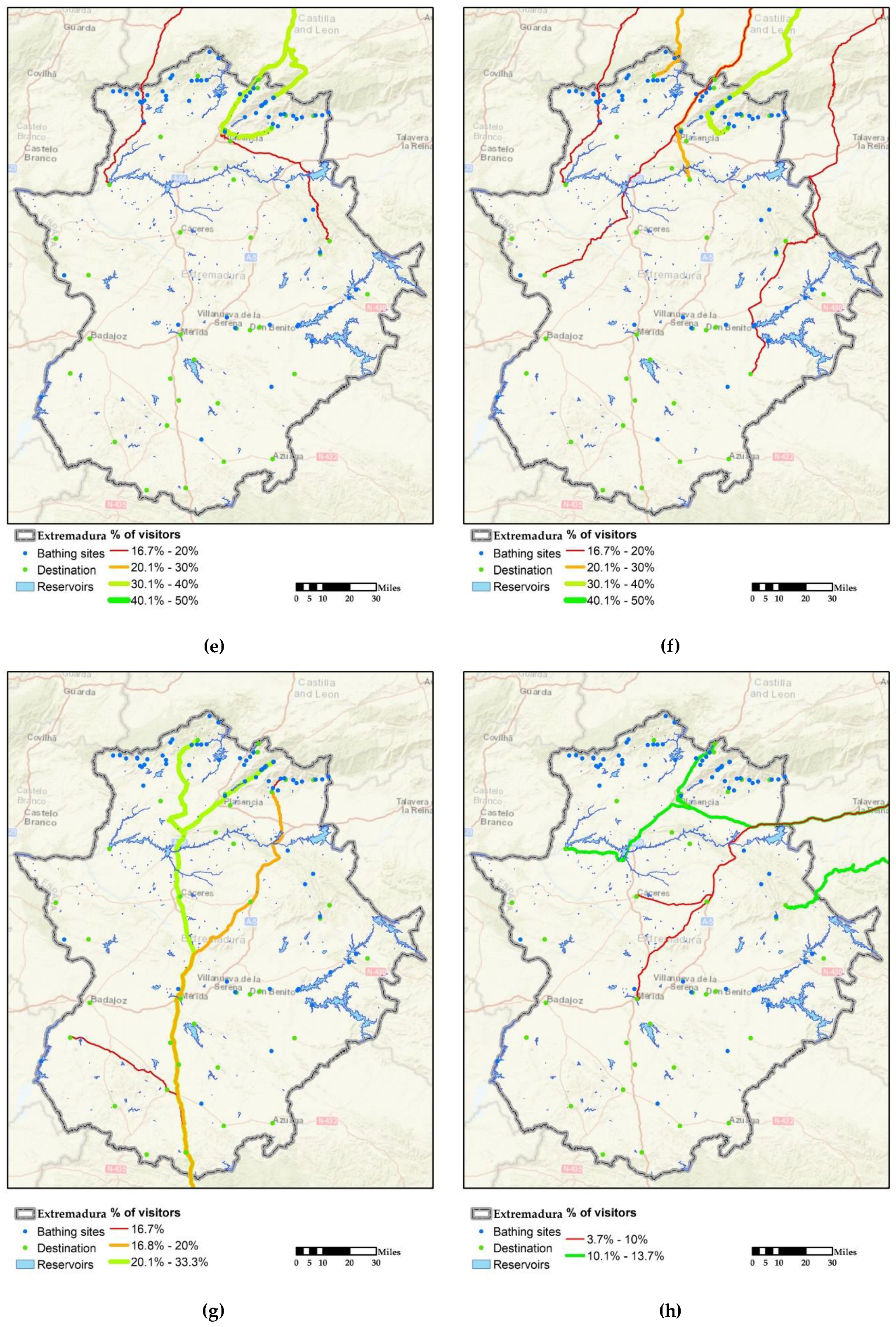

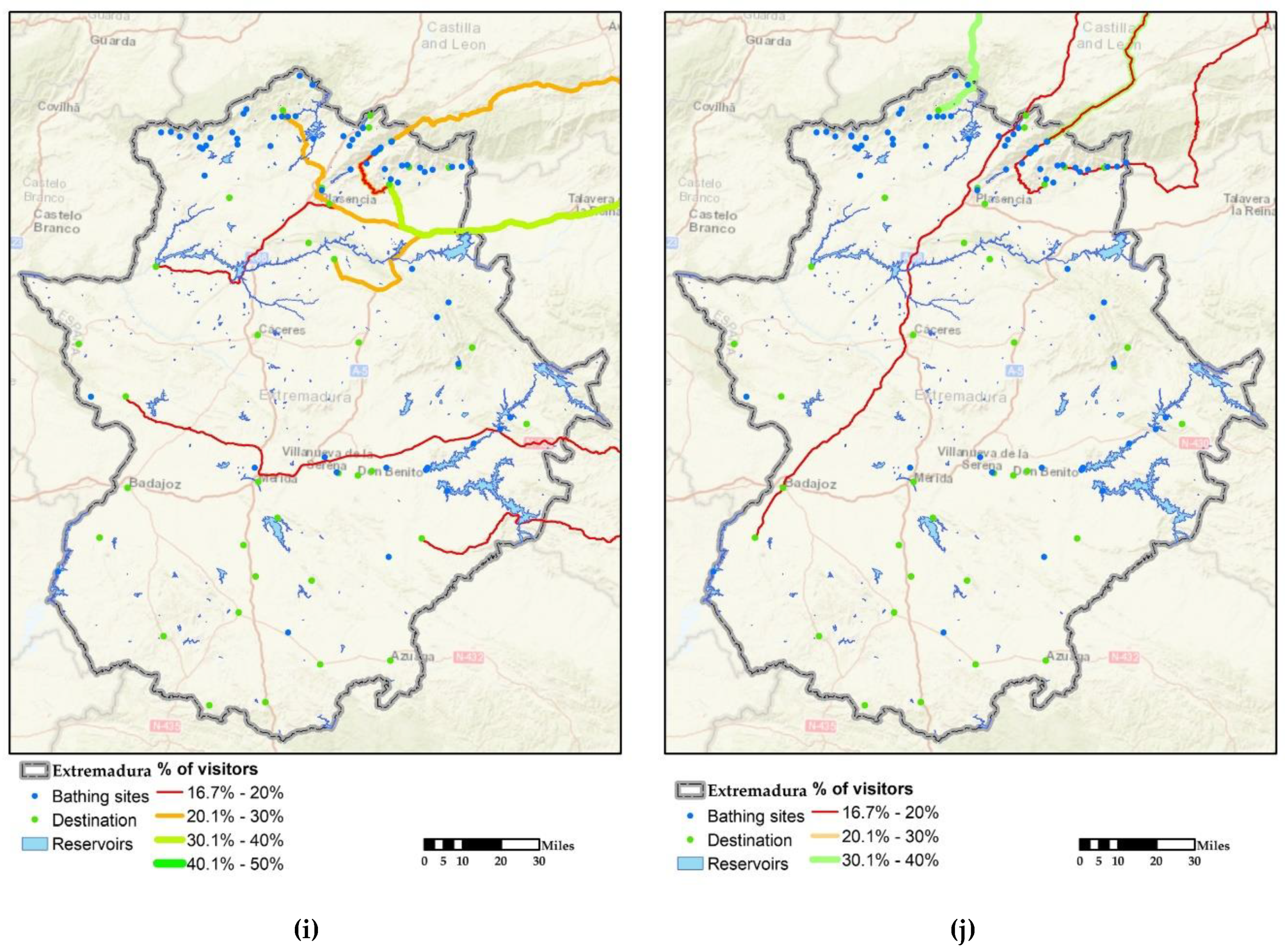

3.3. The Mobility of the Tourist of Inland Waters and the Attraction Capacity of the Destinations

- -

- Those from the province of Vizcaya choose equally the district of La Vera and the Valle del Jerte, although given their origin their holiday destination is also the district of Las Hurdes. Likewise, they visit the area of Monfragüe National Park.

- -

- Tourists from the southern provinces of Cadiz and Seville coincide in choosing above all the destinations located in the north of the province of Cáceres. They clearly put their faith in the municipalities of La Vera, the Valle del Jerte, Valle del Ambroz, and Las Hurdes. However, some reservoir destinations are beginning to appear such as Herrera del Duque and Olivenza.

- -

- Visitors from Madrid choose the areas nearest to those of their origin, which moreover account for an important part of the bathing areas, as is the case in the districts of La Vera and the Valle del Jerte, and they even put their faith in areas in the vicinity of the large reservoirs on the River Guadiana.

- -

- Those coming from Salamanca and Guipúzcoa choose equally the districts of La Vera and the Valle del Jerte, i.e., the areas which are nearest to and have better communications with the cities of Salamanca and San Sebastián.

- -

- Tourists arriving from Valencia mainly coincide in the destinations located in the Valle del Jerte and the district of La Vera, although noteworthy flows to Hervás and Baños de Montemayor in the Valle del Ambroz are also observed.

- -

- On the other hand, visitors from Valladolid prefer Las Hurdes and the Valle del Jerte as their destinations; another important destination is the district of La Vera.

- -

- In contrast, those from the province of Toledo tend to choose the destinations of Guadalupe and the Valle del Ambroz, although their representation never exceeds 15%, the threshold which we have established as significant for drawing up the routes.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- The areas linked to the tourist exploitation of water are very attractive to tourists. Indeed, this resource is the fourth reason given for traveling to Extremadura.

- -

- Tourists who practice activities linked to rivers, reservoirs, and bathing areas make up a demand of a mixed type as they combine these activities with others such as cultural visits, generic rural tourism, birdwatching, and even visits to caves, mines, and places with outstanding geological formations.

- -

- There is a clear predominance of Spaniards over visitors from other countries. Moreover, we are concerned with middle-aged people who travel with their partner or as a family and stay in rural establishments or in camp sites and hotels in accordance with the type of mixed demand they represent.

- -

- The origin of those who are attracted by the water resources of Extremadura is varied with a clear predominance of residents in the large Spanish cities such as Madrid. Barcelona, and Seville, although 13.2% of visitors are residents in the autonomous region itself.

- -

- Accessibility and travel time are important factors for attracting tourists to these spaces, although these are not the only decision-making factors.

- -

- The territory most frequently visited is the northern part of the province of Cáceres which coincides with the areas with the highest number of natural swimming pools; this implies that the resource is mainly exploited in summer.

- -

- Reservoirs are revealed as a potential tourist space as they are capable of attracting visitors spending the night in other spaces, but they do not manage to persuade tourists to stay in the establishments of the surrounding areas.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Origin | Destination | Distance (Miles) | Traveling Time (Minutes) | Rivers, Gorges and Reservoirs Tourism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | Alange | 606 | 593 | 10.3% |

| Barcelona | Alcántara | 601 | 594 | 25.0% |

| Barcelona | Almendralejo | 620 | 595 | 10.0% |

| Barcelona | Badajoz | 639 | 615 | 5.8% |

| Barcelona | Baños de Montemayor | 570 | 548 | 11.1% |

| Barcelona | Cabezuela del Valle | 562 | 558 | 14.3% |

| Barcelona | Cáceres | 575 | 558 | 14.9% |

| Barcelona | Caminomorisco | 575 | 571 | 7.1% |

| Barcelona | Cañamero | 560 | 564 | 15.8% |

| Barcelona | Don Benito | 588 | 568 | 4.0% |

| Barcelona | Guadalupe | 541 | 548 | 10.9% |

| Barcelona | Herrera del Duque | 508 | 529 | 7.7% |

| Barcelona | Hervás | 569 | 546 | 20.7% |

| Barcelona | Hornachos | 626 | 620 | 6.7% |

| Barcelona | Jaraíz de la Vera | 527 | 515 | 30.0% |

| Barcelona | Jarandilla de la Vera | 526 | 521 | 26.7% |

| Barcelona | Jerez de los Caballeros | 664 | 654 | 14.3% |

| Barcelona | Jerte | 525 | 559 | 25.5% |

| Barcelona | Llerena | 624 | 634 | 4.8% |

| Barcelona | Malpartida de Plasencia | 536 | 514 | 21.4% |

| Barcelona | Medellín | 592 | 571 | 12.9% |

| Barcelona | Mérida | 602 | 583 | 10.6% |

| Barcelona | Plasencia | 542 | 528 | 19.9% |

| Barcelona | Torrejón el Rubio | 548 | 533 | 11.1% |

| Barcelona | Trujillo | 548 | 528 | 11.0% |

| Barcelona | Villanueva de la Serena | 590 | 568 | 14.3% |

| Barcelona | Villanueva de la Vera | 516 | 516 | 33.3% |

| Barcelona | Zafra | 641 | 617 | 7.9% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Alange | 434 | 423 | 12.5% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Alcántara | 392 | 399 | 23.1% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Almendralejo | 435 | 422 | 14.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Badajoz | 454 | 440 | 7.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Baños de Montemayor | 303 | 298 | 13.6% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Cáceres | 374 | 367 | 12.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Caminomorisco | 334 | 343 | 27.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Coria | 354 | 346 | 18.8% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Don Benito | 443 | 432 | 20.0% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Guadalupe | 408 | 423 | 6.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Hervás | 310 | 305 | 12.9% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Hornachos | 460 | 455 | 3.7% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Jaraíz de la Vera | 351 | 361 | 28.6% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Jarandilla de la Vera | 361 | 381 | 17.9% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Jerte | 324 | 340 | 31.6% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Malpartida de Plasencia | 338 | 330 | 21.4% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Mérida | 418 | 409 | 9.1% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Monesterio | 478 | 460 | 11.1% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Navaconcejo | 329 | 352 | 14.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Plasencia | 330 | 328 | 17.2% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Torrejón el Rubio | 355 | 367 | 25.0% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Trujillo | 403 | 391 | 8.7% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Villanueva de la Vera | 334 | 379 | 33.3% |

| Bilbao (Vizcaya) | Zafra | 455 | 442 | 3.2% |

| Cadiz | Alange | 191 | 196 | 9.1% |

| Cadiz | Azuaga | 170 | 196 | 14.3% |

| Cadiz | Badajoz | 225 | 226 | 16.0% |

| Cadiz | Cabezuela del Valle | 304 | 314 | 33.3% |

| Cadiz | Cáceres | 237 | 240 | 10.7% |

| Cadiz | Caminomorisco | 312 | 323 | 50.0% |

| Cadiz | Don Benito | 223 | 228 | 18.2% |

| Cadiz | Guadalupe | 271 | 291 | 13.3% |

| Cadiz | Herrera del Duque | 283 | 303 | 23.1% |

| Cadiz | Hervás | 305 | 298 | 9.5% |

| Cadiz | Jaraíz de la Vera | 304 | 302 | 33.3% |

| Cadiz | Jarandilla de la Vera | 308 | 313 | 33.3% |

| Cadiz | Jerez de los Caballeros | 165 | 199 | 12.5% |

| Cadiz | Jerte | 307 | 320 | 25.0% |

| Cadiz | Mérida | 191 | 194 | 9.2% |

| Cadiz | Navaconcejo | 302 | 309 | 27.3% |

| Cadiz | Plasencia | 284 | 282 | 14.3% |

| Cadiz | Trujillo | 248 | 243 | 15.2% |

| Cadiz | Zafra | 158 | 164 | 7.1% |

| Madrid | Alburquerque | 235 | 246 | 14.3% |

| Madrid | Alcántara | 212 | 222 | 13.4% |

| Madrid | Almendralejo | 231 | 223 | 5.4% |

| Madrid | Badajoz | 249 | 242 | 2.5% |

| Madrid | Baños de Montemayor | 181 | 176 | 9.9% |

| Madrid | Cabezuela del Valle | 172 | 186 | 23.5% |

| Madrid | Cáceres | 186 | 186 | 8.9% |

| Madrid | Caminomorisco | 186 | 199 | 16.2% |

| Madrid | Cañamero | 171 | 192 | 13.0% |

| Madrid | Castuera | 224 | 233 | 21.7% |

| Madrid | Coria | 173 | 169 | 8.2% |

| Madrid | Don Benito | 199 | 196 | 7.3% |

| Madrid | Fuentes de León | 286 | 288 | 11.1% |

| Madrid | Guadalupe | 151 | 176 | 6.6% |

| Madrid | Herrera del Duque | 145 | 192 | 17.4% |

| Madrid | Hervás | 179 | 174 | 12.2% |

| Madrid | Jaraíz de la Vera | 138 | 143 | 28.3% |

| Madrid | Jarandilla de la Vera | 137 | 149 | 22.8% |

| Madrid | Jerez de los Caballeros | 275 | 282 | 3.4% |

| Madrid | Jerte | 137 | 182 | 23.0% |

| Madrid | Llerena | 273 | 269 | 5.1% |

| Madrid | Malpartida de Plasencia | 147 | 142 | 19.4% |

| Madrid | Medellín | 203 | 199 | 5.0% |

| Madrid | Mérida | 213 | 210 | 6.8% |

| Madrid | Navaconcejo | 170 | 181 | 21.7% |

| Madrid | Olivenza | 265 | 270 | 2.9% |

| Madrid | Plasencia | 153 | 156 | 10.7% |

| Madrid | Serradilla | 170 | 176 | 12.3% |

| Madrid | Torrejón el Rubio | 158 | 161 | 4.7% |

| Madrid | Trujillo | 158 | 155 | 9.1% |

| Madrid | Valencia de Alcántara | 248 | 262 | 14.3% |

| Madrid | Villafranca de los Barros | 240 | 232 | 8.6% |

| Madrid | Villanueva de la Serena | 200 | 196 | 12.5% |

| Madrid | Villanueva de la Vera | 127 | 144 | 26.2% |

| Madrid | Zafra | 252 | 245 | 3.9% |

| Salamanca | Alcántara | 140 | 163 | 16.7% |

| Salamanca | Cáceres | 125 | 130 | 6.3% |

| Salamanca | Don Benito | 168 | 212 | 14.3% |

| Salamanca | Guadalupe | 159 | 186 | 18.8% |

| Salamanca | Hervás | 60 | 69 | 11.1% |

| Salamanca | Jaraíz de la Vera | 100 | 124 | 33.3% |

| Salamanca | Jerte | 75 | 103 | 30.8% |

| Salamanca | Malpartida de Plasencia | 85 | 97 | 16.7% |

| Salamanca | Mérida | 170 | 174 | 3.0% |

| Salamanca | Olivenza | 196 | 231 | 14.3% |

| Salamanca | Plasencia | 79 | 92 | 14.8% |

| Salamanca | Villanueva de la Serena | 170 | 212 | 4.3% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Alange | 469 | 457 | 5.3% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Alburquerque | 449 | 456 | 20.0% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Alcántara | 426 | 433 | 18.2% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Almendralejo | 469 | 454 | 4.3% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Baños de Montemayor | 337 | 332 | 12.5% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Cabezuela del Valle | 362 | 381 | 100.0% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Cáceres | 409 | 401 | 7.9% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Caminomorisco | 368 | 377 | 100.0% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Castuera | 503 | 502 | 16.7% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Guadalupe | 443 | 457 | 11.1% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Hervás | 344 | 339 | 12.8% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Jaraíz de la Vera | 385 | 394 | 33.3% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Jarandilla de la Vera | 395 | 414 | 13.0% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Jerte | 359 | 374 | 26.7% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Malpartida de Plasencia | 372 | 364 | 14.3% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Mérida | 452 | 443 | 7.5% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Navaconcejo | 364 | 386 | 16.7% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Olivenza | 504 | 502 | 6.7% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Plasencia | 364 | 362 | 13.4% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Torrejón el Rubio | 390 | 401 | 22.2% |

| San Sebastián (Guipúzcoa) | Trujillo | 437 | 425 | 5.1% |

| Seville | Almendralejo | 100 | 103 | 10.0% |

| Seville | Badajoz | 150 | 151 | 3.1% |

| Seville | Baños de Montemayor | 232 | 225 | 7.7% |

| Seville | Cáceres | 163 | 165 | 8.9% |

| Seville | Caminomorisco | 237 | 248 | 33.3% |

| Seville | Guadalupe | 196 | 216 | 9.1% |

| Seville | Hervás | 231 | 223 | 10.4% |

| Seville | Jaraíz de la Vera | 229 | 227 | 20.0% |

| Seville | Jarandilla de la Vera | 234 | 238 | 16.7% |

| Seville | Jerte | 232 | 245 | 33.3% |

| Seville | Mérida | 117 | 119 | 2.7% |

| Seville | Olivenza | 130 | 156 | 16.7% |

| Seville | Plasencia | 209 | 207 | 10.4% |

| Seville | Trujillo | 173 | 168 | 8.3% |

| Seville | Zafra | 83 | 89 | 8.3% |

| Toledo | Alcántara | 190 | 203 | 12.5% |

| Toledo | Baños de Montemayor | 159 | 157 | 11.1% |

| Toledo | Cáceres | 164 | 167 | 3.7% |

| Toledo | Guadalupe | 129 | 157 | 13.6% |

| Toledo | Hervás | 157 | 155 | 6.1% |

| Toledo | Mérida | 191 | 191 | 5.3% |

| Valencia | Alange | 425 | 424 | 5.3% |

| Valencia | Alburquerque | 442 | 449 | 20.0% |

| Valencia | Alcántara | 419 | 424 | 18.2% |

| Valencia | Almendralejo | 439 | 425 | 4.3% |

| Valencia | Baños de Montemayor | 388 | 379 | 12.5% |

| Valencia | Cabezuela del Valle | 380 | 389 | 100.0% |

| Valencia | Cáceres | 393 | 388 | 7.9% |

| Valencia | Caminomorisco | 394 | 402 | 100.0% |

| Valencia | Castuera | 336 | 386 | 16.7% |

| Valencia | Guadalupe | 359 | 378 | 11.1% |

| Valencia | Hervás | 386 | 377 | 12.8% |

| Valencia | Jaraíz de la Vera | 345 | 345 | 33.3% |

| Valencia | Jarandilla de la Vera | 345 | 352 | 13.0% |

| Valencia | Jerte | 383 | 394 | 26.7% |

| Valencia | Malpartida de Plasencia | 354 | 345 | 14.3% |

| Valencia | Mérida | 420 | 413 | 7.5% |

| Valencia | Navaconcejo | 378 | 384 | 16.7% |

| Valencia | Olivenza | 473 | 473 | 6.7% |

| Valencia | Plasencia | 360 | 358 | 13.4% |

| Valencia | Torrejón el Rubio | 366 | 364 | 22.2% |

| Valencia | Trujillo | 367 | 358 | 5.1% |

| Valladolid | Almendralejo | 263 | 257 | 10.0% |

| Valladolid | Badajoz | 258 | 277 | 3.1% |

| Valladolid | Baños de Montemayor | 132 | 135 | 7.7% |

| Valladolid | Cáceres | 203 | 204 | 8.9% |

| Valladolid | Caminomorisco | 162 | 180 | 33.3% |

| Valladolid | Guadalupe | 237 | 259 | 9.1% |

| Valladolid | Hervás | 138 | 142 | 10.4% |

| Valladolid | Jaraíz de la Vera | 178 | 197 | 20.0% |

| Valladolid | Jarandilla de la Vera | 187 | 217 | 16.7% |

| Valladolid | Jerte | 152 | 177 | 33.3% |

| Valladolid | Mérida | 247 | 247 | 2.7% |

| Valladolid | Olivenza | 274 | 305 | 16.7% |

| Valladolid | Plasencia | 156 | 164 | 10.4% |

| Valladolid | Trujillo | 208 | 239 | 8.3% |

| Valladolid | Zafra | 284 | 279 | 8.3% |

References

- Zimmermann, E.W. World Resources and Industries: A Functional Appraisal of the Availability of Agricultural and Industrial Resources; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1933; p. 842. [Google Scholar]

- Bullón, R. Planificación del Espacio Turístico; Trillas: México D.F, Mexico, 1985; p. 246. [Google Scholar]

- Acerenza, M.A. Administración del Turismo-vol. 1. Conceptualización y Organización; Trillas: México D.F., Mexico, 1984; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Gurría, M. Introducción al Turismo; Trillas: México D.F, Mexico, 1991; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, D. Recursos turísticos y atractivos turísticos: conceptualización, clasificación y valoración. Cuad. De Tur. 2015, 35, 335–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaner, J.; Antich, J.; Arcarons, R. Diccionario de Trusimo; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1998; p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Sánchez, M.; Rengifo, J.I. La evaluación del potencial para el desarrollo del turismo rural. Aplicación metodológica sobre la provincia de Cáceres. Rev. Int. De Cienc. Y Tecnol. De La Inf. Geográfica 2013, 13, 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Martín, L.M. Characterization of the Tourist Demand of the Villuercas–Ibores–Jara Geopark: A Destination with the Capacity to Attract Tourists and Visitors. Geoscice 2019, 9, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Sánchez, M.; Rengifo, J.I. Patrones de distribución de la oferta turística mediante técnicas geoestadísticas en Extremadura (2004-2014). Boletín De La Asoc. De Geógrafos Españoles 2018, 76, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Blas, R. Hot Spot Analysis versus Cluster and Outlier Analysis: An Enquiry into the Grouping of Rural Accommodation in Extremadura (Spain). Isprs Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Blas, R.; Rengifo, J.I. The Dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A Potential for Socio-economic Development Based on Agritourism Activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Martín, L.M. Tourist Mobility at the Destination Toward Protected Areas: The Case-Study of Extremadura. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defert, P. Les Ressources et les activités touristiques: essai d’intégration. Les Cah. Du Tour. 1972, 19, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- OEA. Metodología de Inventario Turístico; CICATUR: Perú, Ecuador, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Gurría, J.L.; Leco, F.; Pérez, M.N. SIG para el desarrollo turístico en los espacios rurales de Extremadura. Estud. Geográficos 2001, 243, 335–368. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, M. El embalse del Ebro y su potencial turístico: la apuesta por un nuevo modelo de desarrollo rural. Boletín De La Inst. Fernán González 2000, 220, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Andrades, L. Planificación turística y sostenible. Aplicación a un destino de costa interior de Extremadura: el embalse de la serena. Rev. De Estud. Empresariales 2008, 2, 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Salvá, P. Los modelos de desarrollo turístico en el Mediterráneo. Cuad. De Tur. 1998, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.; Alburquerque, F. El turismo cultural y el de sol y playa: ¿sustitutivos o complementarios? Cuad. De Tur. 2003, 11, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- García, N.; Quintero, Y. Producto de sol y playa para el desarrollo turístico del Municipio Trinidad de Cuba. Rev. Interam. De Ambiente Y Tur. 2018, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L. Agua y turismo. Nuevos usos de los recursos hídricos en la península Ibérica. Enfoque integral. Boletín De La Asoc. De Geógrafos Españoles 2004, 37, 239–255. Available online: https://bage.age-geografia.es/ojs/index.php/bage/article/view/1985/1898 (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Campesino, A.-J. Paisajes del agua y turismo fluvial en la Raya ibérica. In Paisaje, Cultura Territorial y Vivencia de la Geografía. Libro Homenaje al Profesor Alfredo Morales Gil; Vera, J.F., Olcina, J., Hernández, M., Eds.; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2016; pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lacosta, A.J. La configuración de nuevos destinos turísticos de interior en España a partir del turismo activo y de aventura. Cuad. Geográficos 2004, 34, 11–31. Available online: http://www.ugr.es/~cuadgeo/docs/articulos/034/034-001.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Prat, J.M.; Cànoves, G. El turismo cultural como oferta complementaria en los destinos de litoral. El caso de la Costa Brava (España). Investig. Geográficas 2012, 79, 119–135. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3141405/El_turismo_cultural_como_oferta_complementaria_en_los_destinos_de_litoral._El_caso_de_la_Costa_Brava_Espa%C3%B1a_ (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Cànoves, G.; Prat, J.M.; Blanco, A. Turismo en España, más allá del sol y la playa. Evolución reciente y cambios en los destinos de litoral hacia un turismo cultural. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 2016, 71, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. Historia del Turismo en España en el s. XX; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2007; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M. Tipología Turística Munic. De Extremad. Basada En El Análisis Factorial De Compon. Principales. Lurralde 1998, 21, 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Boletín Oficial del Estado, Gobierno de España. Ley 45/2007, de 13 de diciembre, para el desarrollo sostenible del medio rural. Madrid: s.n. 2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/13/45/con (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Cruz, M.A.; Agatón, D.; Añorve, N.N. El agua desde la economía circular: base para el turismo ustentable y el desarrollo local en Acapulco. In Impacto Socio-ambiental, Territorios Sostenibles y Desarrollo Regional Desde el Turismo; Pérez, E., Mota, V.E., Eds.; UNAM: México D.F., Mexico, 2018; pp. 483–501. [Google Scholar]

- Hortelano, L.A.; Martín, M.L. Territorio, patrimonio y turismo en la Raya de Castilla y León. Available online: https://buleria.unileon.es/handle/10612/8438 (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- Hortelano, L.A. Patrimonio territorial como activo turístico en la «Raya» de Castilla y León con Portugal. Cuad. De Tur. 2015, 36, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, A.; García, J.; del Río, M.C. La investigación en turismo activo. Revisión bibliográfica (1975-2013). Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5019878 (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- González, S.; Rubio, A. Big Data y Turismo Deportivo: Estado de la cuestión y nuevas aplicaciones. Eracle. J. Sport Soc. Sci. 2019, 2, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvis, N. Turismo fluvial: una alternativa para fomentar la actividad turística en los municipios ribereños al río Magdalena: El caso del municipio de Suárez (Tolima, Colombia). Available online: https://revistas.uexternado.edu.co/index.php/tursoc/article/view/5587 (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Moreira, C. River tourism, leisure in inland waterways and local and regional development. Cad. De Geogr. 2018, 38, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muryani, C.; Santoso, S.; Utomowati, R. Potential Analysis and Development of Reservoir Water for Ecotourism at Gajah Mungkur Wonogiri. In Proceedings of the 1st UPI International Geography Seminar, Bandung, Indonesia, 8 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Xiao, Y. The effect of rural tourism development on the farmers’ life satisfaction in Three Gorges Reservoir, China. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2017, 20, 1455–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muryani, C.; Rindarjono, M.G. Community-Based Tourism Development at Gajah Mungkur Wonogiri Tourist Attraction. In Proceedings of the 1st UPI International Geography Seminar, Bandung, Indonesia, 8 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Isdarmanto, I. Analysis Strategy of Tourism Development at Kalibiru, Kulon Progo as A Leading Tourist Attracction in Yogyakarta Special Region. J. Stipram 2016, 10, 1–12. Available online: http://ejournal.stipram.ac.id/index.php/kepariwisataan/article/view/87/84 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

- Beutel, M.; Horne, A. A Review of the Effects of Hypolimnetic Oxygenation on Lake and Reservoir Water Quality. Lake Reserv. Manag. 2009, 15, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tnag, Q.; Fu, B.; Collins, A.; Wen, A.; He, X.; Bao, Y. Developing a sustainable strategy to conserv reservoir marginal landscapes. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boryczko, K.; Bartoszek, L.; Koszelnik, P.; Rak, J. A new concept for risk analysis relating to the degradation of water reservoirs. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 25591–25599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, B.-J.; Qi, J.; Dong, J. Water Conservation Scenic Spots in China: Developing the Tourism Potential of Hydraulic Projects and Water Resources. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Galizia, J. Water Resources Management; Scienza: São Carlos, Brazil, 2018; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

- Duda-Gromada, K.; Bujdosó, Z.; David, L. Lakes, reservoirs and regional development trough some examples in Poland and Hungary. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2010, 5, 16–23. Available online: http://gtg.webhost.uoradea.ro/PDF/GTG-1-2010/2-GTG-Katarzyna.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Cooper, C. Lakes as Tourism Destination Resources. In Lake Tourism. An Integrated Approach to Lacustrine Tourism Systems; Hall, C.M., Härkönen, T., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M.; Härkönen, T. Lake Tourism: An Introduction to Lacultrine Tourism Systems. In Lake Tourism. An Integrated Approach to Lacustrine Tourism Systems; Channel View Publications: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.; Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I. Methodological approach for assessing the potential of a rural tourism destination: An application in the province of Cáceres (Spain). Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, J. River related tourism in Europe—an overview. GeoJournal 1995, 35, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Timothy, D.J.; Cooper, M. Introducing River Tourism: Physucal, ecological and Human Aspects. In River Tourism; Prideaux, B., Cooper, M., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2009; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. River Tourism. In Rivers and Society. Landscapes, Governance and Livelihoods; Cooper, M., Chakraborty, A., Chakraborty, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Deiminiat, A.; Shojaee, H.; Eslamian, S. Tourism an River Environment. In Handbook of Engineering Hydrology: Environmental Hydrology and Water Management; Slamian, S., Ed.; Taylor; Francis Group: London, UK, 2014; pp. 401–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, J.M. Atractivos naturales y culturales vs. desarrollo turístico en la raya Luso-Extremeña. Pasos 2016, 14, 907–928. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I.; Sánchez, M. Caracterización espacial del turismo en Extremadura mediante análisis de agrupamiento (grouping analysis). Geofocus 2017, 19, 207–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M. Anuario de Oferta y Demanda Turística de Extremadura por Territorios. Año 2017; Junta de Extremadura: Mérida, Spain, 2018; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Hoteles: encuesta de ocupación, índice de precios e indicadores de rentabilidad. Available online: https://ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?padre=5939&capsel=5927 (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Sánchez, J.M.; Sánchez, M. Sinergias turísticas en entornos rurales: etre el mito y la realidad. El caso del Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara. In Proceedings of theCongreso Internacional de Turismo Rural y Desarrollo Sostenible, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 19–21 October 2016; pp. 433–448. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M. Propuesta Metodológica Para la Generación de Información Climática en la Provincia de Cáceres. Resultados Municipales; Universidad de Extremadura; Junta de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 1995; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I. Evolución del sector turístico en la Extremadura del siglo XXI: auge, crisis y recuperación. Lurralde 2019, 42, 19–50. Available online: http://www.ingeba.org/lurralde/lurranet/lur42/42sanchez.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Instituto Geográfico Nacional. Base Topográfica Nacional 1:100,000 (BTN100). Available online: http://www.ign.es/web/resources/docs/IGNCnig/CBG%20-%20BTN100.pdf. (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Sistema de Información Territorial de Extremadura. Centro de descargas SITEX. Available online: http://sitex.gobex.es/SITEX/centrodescargas. (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Junta de Extremadura. Extremadura Turismo. Available online: http://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/organiza-tu-viaje/donde-alojarse/index.html. (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Sánchez, J.M. El Sistema de Información Geográfica como herramienta de planificación turística. Una aplicación para la localización idónea de alojamientos rurales en la provincia de Cáceres. Estudios Turísticos 2009, 62, 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Rengifo, J.I. Los Espacios Naturales Protegidos y su Capacidad de Atracción Turística: Referencias al Parque Nacional de Monfragüe; (Intellectual Capital and Regional Development: New landscapes and challenges for space planning); APDR: Covilhâ, Portugal, 2017; pp. 1196–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Sánchez, J.M. Geotourist Profile Identification Using Binary Logit Modeling: Application to the Villuercas-Ibores-Jara Geopark (Spain). Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.M.; Leco, F.; Gurría, J.L.; Pérez, M.N. La planificación del turismo rural sostenible en Extremadura mediante Sistemas de Información Geográfica. Available online: http://tig.age-geografia.es/docs/IX_3/Sanchez_JoseManuel.PDF (accessed on 22 February 2020).

- van Balen, M.; Dooms, M.; Haezendonck, E. River tourism development: The case of the port of Brussels. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 13, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooms, M.; Haezendonck, E.; Valaert, T. Dynamic green portfolio analysis for inland ports: An. empirical analysis on Western Europe. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinger, A.; Zins, A. Usage of Location Based River Cruise Information Systems—Industry Views and User Acceptance. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2008, 17, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ni, R.; Hou, Y. Cruise Tourism Integration and Regional Tourism Integration in the Yangtze River Delta. In Report on the Development of Cruise Industry in China; Wang, H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Travelers | Spanish Travelers | Foreign Travelers | Overnight Stays | Average Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Heritage Cities 1 | 536,348 | 437,571 | 98,777 | 836,046 | 1.56 | |

| Other cultural cities 1 | 449.525 | 363,666 | 85,859 | 737,253 | 1.64 | |

| Northern area of Extremadura 2 | Hotels | 267,803 | 228,587 | 39,216 | 544,814 | 2.03 |

| Rural accommodation | 123,302 | 117,733 | 5569 | 283,149 | 2.30 | |

| Camping | 71,875 | 62,511 | 9364 | 213,062 | 2.96 | |

| Area Type | Characteristics | Accommodation Vacancies * |

|---|---|---|

| Reservoirs (>500 hectares) | 63,811 hectares and 1859 miles of perimeter | 3732 |

| Rivers (principal) | 387 miles of length | 7087 |

| Bathing sites | 68 areas | 14,504 |

| Northern area of Extremadura | 396,151 hectares | 15,447 |

| World Heritage Sites | 2 cities and 1 Monastery | 6680 |

| Other Cultural Towns | 4 cities | 4869 |

| Sample Characteristics | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Universe: | 1,843,175 travellers in Extremadura (2017) |

| Size of sample: | 3403 surveys |

| Level of confidence | 95% |

| Sample error for the worst-case scenario (pq = 50) and the best scenario (pq = 90%) | 1.68%/1.01% |

| Data type | Source | Cartographic Information | Alphanumeric Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cartographic | IGN | Administrative units Altimetry Hydrography Population centers Transport system | Area Altitude Order Type Type |

| SITEX | Bathing sites | Characteristics | |

| Alphanumeric | Extremadura Tourism | Georeferencing information on Google Maps | Type of accommodation Address Municipality Accommodation vacancies |

| Motivation | Replies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural visits | 10,974 | 79.2% |

| Rural tourism | 6708 | 48.4% |

| Gastronomy | 5403 | 39.0% |

| Tourism in rivers and gorges or reservoirs | 3402 | 24.6% |

| Birdwatching | 1618 | 11.7% |

| Visiting mines or caves and geological formations | 966 | 7.0% |

| Practicing sport | 958 | 6.9% |

| Visiting wine cellars | 708 | 5.1% |

| Participating in events (congresses or meetings) | 638 | 4.6% |

| Observing the sky | 418 | 3.0% |

| Visiting scenarios of films or TV series | 169 | 1.2% |

| Learning Spanish | 148 | 1.1% |

| Hunting | 82 | 0.6% |

| Motivation | Tourism in Rivers and Gorges or Reservoirs | Chi-Square | Symmetric Measurements | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Value | Levels of Freedom | Asymptotic Meaning | Phi | Tau-b Kendall | R Intervals | ||

| Learning Spanish | Yes | 1.40% | 98.60% | 4995 | 1 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.019 |

| No | 1.00% | 99.00% | |||||||

| Hunting | Yes | 0.60% | 99.40% | 0.228 | 1 | 0.633 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| No | 0.60% | 99.40% | |||||||

| Gastronomy | Yes | 43.70% | 56.30% | 42.272 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.055 |

| No | 37.50% | 62.50% | |||||||

| Birdwatching | Yes | 20.50% | 79.50% | 343.302 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.157 | 0.157 |

| No | 8.80% | 91.20% | |||||||

| Observing the sky | Yes | 6.50% | 93.50% | 189.490 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.117 | 0.117 | 0.117 |

| No | 1.90% | 98.10% | |||||||

| Participating in events (congresses or meetings) | Yes | 2.50% | 97.50% | 45.627 | 1 | 0.000 | −0.057 | −0.057 | −0.057 |

| No | 5.30% | 94.70% | |||||||

| Practising sport | Yes | 9.20% | 90.80% | 36.488 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

| No | 6.20% | 93.80% | |||||||

| Rural tourism | Yes | 65.50% | 34.50% | 523.165 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.194 | 0.194 | 0.194 |

| No | 42.90% | 57.10% | |||||||

| Visiting wine cellars | Yes | 5.60% | 94.40% | 2.622 | 1 | 0.105 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| No | 4.90% | 95.10% | |||||||

| Visiting scenarios of films or TV series | Yes | 2.10% | 97.90% | 32.038 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 |

| No | 0.90% | 99.10% | |||||||

| Visiting mines or caves and geological formations | Yes | 11.90% | 88.10% | 168.852 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.110 |

| No | 5.40% | 94.60% | |||||||

| Cultural visits | Yes | 77.30% | 22.70% | 9.996 | 1 | 0.002 | −0.027 | −0.027 | −0.027 |

| No | 79.90% | 20.10% | |||||||

| Sex | Will You Stay in Extremadura? | Accommodation Used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 51.4% | Yes | 89.3% | Tourist albergue | 1.3% |

| Male | 47.3% | No | 9.7% | Tourist apartment | 6.6% |

| DK/NA | 1.3% | DK/NA | 1.0% | Camp site | 8.8% |

| Age | Number of overnight stays | Staying with relatives | 16.5% | ||

| Between 18 and 25 | 4.6% | 1 | 5.6% | Casa rural | 15.8% |

| Between 26 and 35 | 15.0% | 2 | 20.5% | Hostelry | 3.1% |

| Between 36 and 45 | 28.3% | 3 | 15.4% | Hostel or guest house | 5.4% |

| Between 46 and 55 | 26.4% | 4 | 12.6% | Spa hotel | 2.3% |

| Between 56 and 65 | 18.7% | ≥5 | 35.2% | 1 to 3-star hotel | 17.0% |

| Over 65 | 6.6% | No overnight stay | 10.7% | 4 to 5-star hotel | 11.5% |

| DK/NA/REF | 0.4% | Companions | Rural hotel | 5.3% | |

| With a partner | 49.9% | Other accommodation | 5.4% | ||

| With relatives | 28.2% | DK/NA/REF | 1.1% | ||

| With Friends | 14.3% | Origin | |||

| Alone | 4.7% | Spain | 92.4% | ||

| In a group (organised trip) | 2.8% | Other countries | 7.3% | ||

| DK/NA | 0.2% | DK/NA | 0.3% | ||

| Provinces Issuing Most Visitors Attracted by Water Masses | |

|---|---|

| Madrid | 24.8% |

| Barcelona | 7.2% |

| Seville | 5.4% |

| Vizcaya | 4.3% |

| Valencia | 2.5% |

| Guipúzcoa | 2.5% |

| Toledo | 2.4% |

| Cadiz | 2.2% |

| Salamanca | 2.0% |

| Valladolid | 1.9% |

| Badajoz | 8.3% |

| Cáceres | 4.9% |

| Rest of provinces | 31.6% |

| Population Centres and Accommodation Places | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alange | 458 | Don Benito | 333 | Mérida | 2505 |

| Alburquerque | 84 | Fuentes de León | 88 | Monesterio | 391 |

| Alcántara | 152 | Guadalupe | 759 | Navaconcejo | 660 |

| Almendralejo | 503 | Herrera del Duque | 149 | Olivenza | 341 |

| Azuaga | 143 | Hervás | 1976 | Plasencia | 1498 |

| Badajoz | 1884 | Hornachos | 85 | Torrejón el Rubio | 295 |

| Baños de Montemayor | 657 | Jaraíz de la Vera | 215 | Trujillo | 1213 |

| Cabezuela del Valle | 207 | Jarandilla de la Vera | 1624 | Valencia de Alcántara | 359 |

| Cáceres | 3609 | Jerez de los Caballeros | 323 | Villafranca de los Barros | 187 |

| Caminomorisco | 566 | Jerte | 739 | Villanueva de la Serena | 182 |

| Cañamero | 106 | Llerena | 200 | Villanueva de la Vera | 196 |

| Castuera | 133 | Malpartida de Plasencia | 667 | Zafra | 715 |

| Coria | 193 | Medellín | 46 | TOTAL | 24,441 |

| Origin (Province) | Origin (City) | Minimum Distance to Destinations (Minutes) | Minimum Distance to Destinations (Minutes) | Population (Province) 1 January 2019 | Percentage of Travelers (Average) | Centre of Attraction for Emigrants from Extremadura | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barcelona | Barcelona | 514 | 660 | 5.663.284 | 7.2% | Yes | −0.576 |

| Vizcaya | Bilbao | 298 | 492 | 1.152.200 | 4.3% | Yes | −0.616 |

| Cadiz | Cadiz | 137 | 329 | 1.240.020 | 2.2% | No | 0.444 |

| Madrid | Madrid | 142 | 288 | 6.661.949 | 24.8% | Yes | −0.559 |

| Salamanca | Salamanca | 62 | 256 | 329.866 | 2.0% | No | −0.315 |

| San Sebastián | Guipúzcoa | 332 | 526 | 723.412 | 2.5% | Yes | −0.538 |

| Seville | Seville | 62 | 254 | 1.941.804 | 5.4% | No | 0.419 |

| Toledo | Toledo | 123 | 353 | 694.395 | 2.4% | No | −0.160 |

| Valencia | Valencia | 329 | 485 | 2.563.887 | 2.5% | No | −0.178 |

| Valladolid | Valladolid | 135 | 329 | 519.444 | 1.9% | No | −0.399 |

| Municipalities and Accommodation Places | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasencia | 1498 | Caminomorisco | 566 | Cabezuela del Valle | 207 |

| Jerte | 739 | Alcántara | 152 | Baños de Montemayor | 657 |

| Jaraíz de la Vera | 215 | Malpartida de Plasencia | 667 | Torrejón el Rubio | 295 |

| Jarandilla de la Vera | 1624 | Guadalupe | 759 | Villanueva de la Vera | 196 |

| Hervás | 1976 | Navaconcejo | 660 | TOTAL | 10,211 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Martín, J.-M.; Sánchez-Rivero, M.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I. Water as a Tourist Resource in Extremadura: Assessment of Its Attraction Capacity and Approximation to the Tourist Profile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041659

Sánchez-Martín J-M, Sánchez-Rivero M, Rengifo-Gallego J-I. Water as a Tourist Resource in Extremadura: Assessment of Its Attraction Capacity and Approximation to the Tourist Profile. Sustainability. 2020; 12(4):1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041659

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Martín, José-Manuel, Marcelino Sánchez-Rivero, and Juan-Ignacio Rengifo-Gallego. 2020. "Water as a Tourist Resource in Extremadura: Assessment of Its Attraction Capacity and Approximation to the Tourist Profile" Sustainability 12, no. 4: 1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041659

APA StyleSánchez-Martín, J.-M., Sánchez-Rivero, M., & Rengifo-Gallego, J.-I. (2020). Water as a Tourist Resource in Extremadura: Assessment of Its Attraction Capacity and Approximation to the Tourist Profile. Sustainability, 12(4), 1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041659