Consumers’ Perception and Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Italian Hypermarkets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey

2.2. Data Analysis

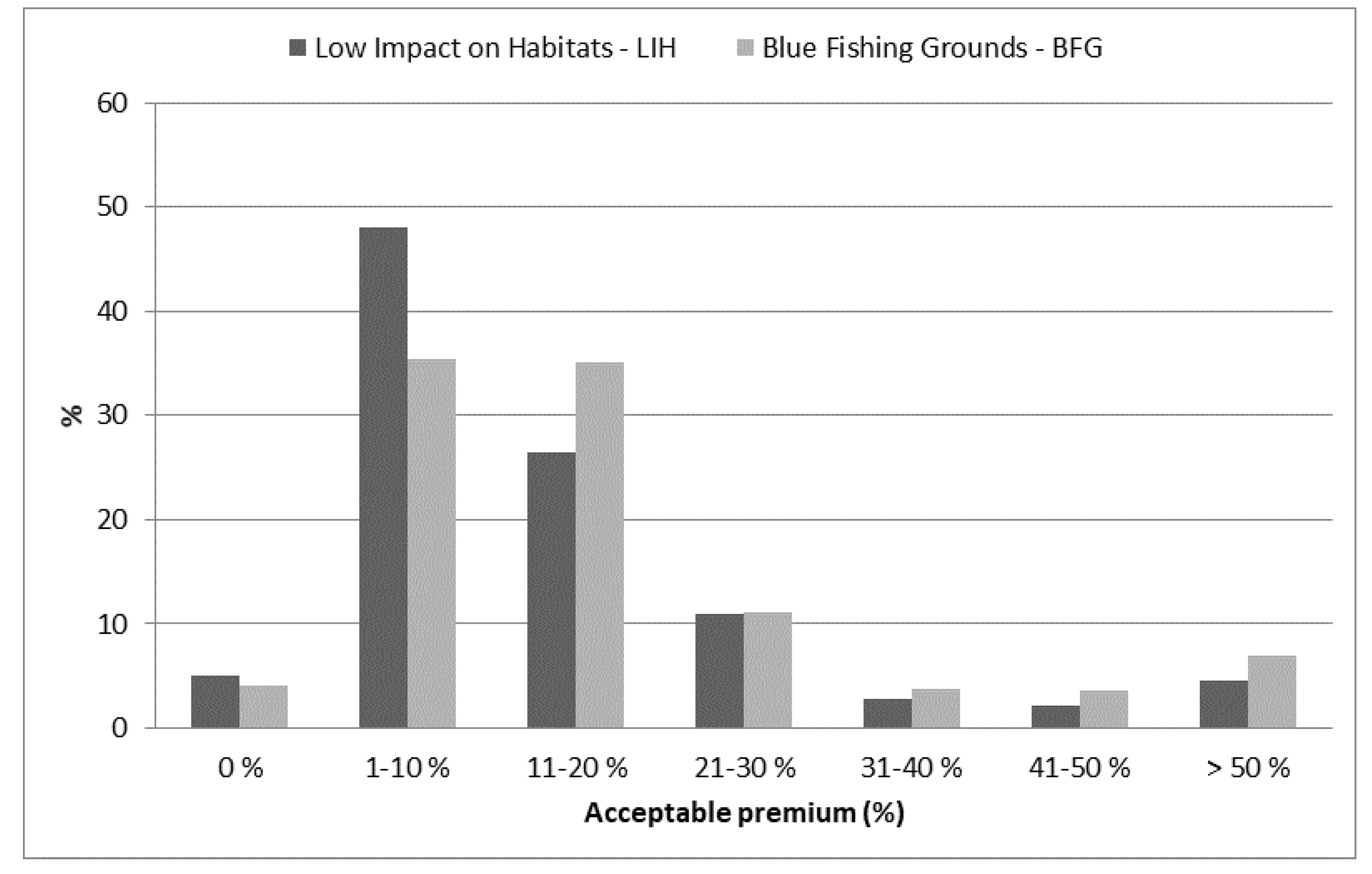

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, L.Q.; Du, Q.; Friedrichs, Y.V. Effectiveness of Eco-Label? A Study of Swedish University Students’ Choice on Ecological Food. Master Thesis, Umeå School of Business, Umeå, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maesano, G.; Carra, G.; Vindigni, G. Sustainable dimensions of seafood consumer purchasing behaviour: A review. Calitatea 2019, 20, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. 1995. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/v9878e/v9878e00.htm (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Sogn-Grundvåga, G.; Larsena, T.A.; Youngb, J.A. The value of line-caught and other attributes: An exploration of price premiums for chilled fish in UK supermarkets. Mar. Policy 2013, 38, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brécard, D.; Lucas, S.; Pichot, N.; Salladarré, F. Consumer Preferences for Eco. Health and Fair Trade Labels. An Application to Seafood Product in France. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2012, 10, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). Sustainable Consumption. Facts and Trends. For a Business Perspective. 2008. Available online: http://www.wbcsd.org/Clusters/Sustainable-Lifestyles/Resources/Sustainable-Consumption-Fact-and-Trends-From-a-Business-Perspective (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Clonan, A.; Holdsworth, M.; Swift, J.A.; Leibovici, D.; Wilson, P. The dilemma of healthy eating and environmental sustainability: The case of fish. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 15, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, H. Heterogeneous Consumer Preference for Seafood Sustainability in Japan. 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/92390/ (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Jonell, M.; Crona, B.; Brown, K.; Rönnbäck, P.; Troell, M. Eco-Labeled Seafood: Determinants for (Blue) Green Consumption. Sustainability 2016, 8, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, M.; Almendarez-Hernández, M.; Avilés-Polanco, G.; Beltrán-Morales, L.F. Consumer Acceptance of Eco-Labeled Fish: A Mexican Case Study. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4625–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Thornton, T.F. Can Consumers Understand Sustainability through Seafood Eco-Labels? A U.S. and UK Case Study. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8195–8217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffry, S.; Pickering, H.; Ghulam, Y.; Whitmarsh, D.; Wattage, P. Consumer choices for quality and sustainability labeled seafood products in the UK. Food Policy 2004, 29, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Roheim, C.A. A battle of taste and environmental convictions for ecolabeled seafood: A contingent ranking experiment. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2006, 31, 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmarsh, D.; Wattage, P. Public attitude towards the environmental impact of salmon aquaculture in Scotland. Eur. Environ. 2006, 16, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salladarré, F.; Guillotreau, P.; Perraudeau, Y.; Montfort, M.C. The demand for seafood eco-labels in France. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zander, K.; Feucht, Y. Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Seafood Made in Europe. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2018, 30, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, C.R.; Johnston, R.J.; Donath, H. Assessing consumer preferences for ecolabeled seafood: The influence of species, certifier and household attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1999, 81, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, T.; Phillips, B. Seafood Ecolabelling. Principles and Practice, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Piroddi, C.; Coll, M.; Liquete, C.; Macias, D.; Greer, K.; Buszowski, J.; Steenbeek, J.; Danovaro, R.; Christensen, V. Historical changes of the Mediterranean Sea ecosystem: Modelling the role and impact of primary productivity and fisheries changes over time. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlucci, F.; Cirà, A.; Forte, E.; Siviero, L. Infrastructure and logistics divide: Regional comparisons between North Eastern & Southern Italy. Technol. Econ. Dev. Ecol. 2017, 23, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. Il Tuo Accesso Diretto alla Statistica Italiana. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_POPRES1# (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Dipartimento delle FInanze. Analisi Statistiche. Available online: https://www1.finanze.gov.it/finanze3/analisi_stat/index.php?page=1&tree=2014AAPFTOT0106&&&export=0&media=media&&&&&& (accessed on 27 December 2019).

- Brécard, D.; Hlaimi, B.; Lucas, S.; Perraudeau, Y.; Salladarré, F. Determinants of demand for green products: An application to eco-label demand for fish in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zeng, Y.; Fong, Q.; Lone, T.; Liu, Y. Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for green- and eco-labeled seafood. Food Control 2012, 28, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwann, C. Eco-labelling: A new deal for a more durable fishery management? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyert, W.; Sagarin, R.; Annala, J. The promise and pitfalls of Marine Stewardship Council certification: Maine lobster as a case study. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S.S. Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, 3rd ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling, H. Analysis of a Complex of Statistical Variables into Principal Components. J. Educ. Psychol. 1933, 24, 417–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, J.J. Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica 1979, 47, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.J.; Wessells, C.R.; Donath, H.; Asche, F. Measuring Consumer Preferences for Ecolabeled Seafood: An International Comparison. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2001, 26, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, F.; Johansson-Stenman, O. Willingness to pay for improved air quality in Sweden. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, D.P. Do children matter? An examination of gender differences in environmental valuation. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J. Understanding the Determinants of Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Products: An Empirical Analysis of the China Environmental Label. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2012, 5, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giosuè, C.; Gancitano, V.; Sprovieri, M.; Bono, G.; Vitale, S. A responsible proposal for Italian seafood consumers’. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrewwstevens. Available online: http://andrewwstevens.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Seafood.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2018).

- Vitale, S.; Giosuè, C.; Biondo, F.; Bono, G.; Boscaino, G.; Sprovieri, M.; Attanasio, M. Are People Willing to Pay for Eco-Labeled Wild Seafood? An Overview. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, J.; Hallstein, E.; Stevens, A.W.; Villas-Boas, S.B. Measuring Willingness to Pay for Environmental Attributes in Seafood. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 73, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hu, W.; Huang, W. Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Sustainable Products? A Study of Eco-Labeled Tuna Steak. Sustainability 2016, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roheim, C.A.; Asche, F.; Santos, J.I. The elusive price premium for ecolabeled products: Evidence from seafood in the UK market. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, V.; Colloca, F. Recent trends in the productivity of the Italian trawl fishery: The importance of the socio economic context and overexploitation. Mar. Policy 2018, 87, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | No. of Questions | Question Type | Response Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall fishing knowledge | 9 | 7 Questions: Dichotomous 2 Questions: Multiple-choice | All closed |

| Environmental motivations | 3 | All dichotomous | All closed |

| Intrinsic motivations | 7 | 4 Questions: Multiple-choice 2 Questions: Dichotomous | 6 closed and 1 open |

| Qualitative seafood preference | 4 | 1 Question: Multiple-choice | 1 closed and 3 open |

| Willingness to pay (WTP) for Eco-labeled anchovy | 5 | 3 Questions: Dichotomous | 3 closed and 2 open |

| Italia | Sample (n = 560) | Palermo (n = 322) | Milano (n = 238) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | % Dis. | Obs. | % Dis. | % Dis. | % Dis. |

| Gender | 560 | ||||

| Female | 51.3% a | 51.8% | 54.0% | 49.6% | |

| Male | 48.7% a | 48.2% | 46.0% | 50.4% | |

| Age (years) | 545 | ||||

| 18–25 | 11.2% a | 2.1% | 2.2% | 2.1% | |

| 26–45 | 28.7% a | 34.2% | 28.9% | 39.5% | |

| 46–65 | 34.1% a | 45.3% | 49.4% | 41.2% | |

| > 65 | 26% a | 18.4% | 19.6% | 17.2% | |

| Income earners | 528 | ||||

| Yes | 67% b | 79.8% | 77.6% | 82.0% | |

| No | 33% b | 20.2% | 22.4% | 18.0% | |

| Income (€/month) | 341 | ||||

| < 1000 | 30.6% b | 11.6% | 14.5% | 8.8% | |

| 1000–1999 | 39.1% b | 58.1% | 58.8% | 57.4% | |

| 2000–3000 | 12.7% b | 24.3% | 20.9% | 27.8% | |

| > 3000 | 17.6% b | 5.9% | 5.8% | 6.0% | |

| Weighable Factors | Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Specialized fishing magazines | 0.428 | |||

| Scientific magazines | 0.695 | |||

| Publications from professionals | 0.773 | |||

| Campaigns and documents for environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) | 0.787 | |||

| Initiatives emanating from Ministries and/or Local Bodies | 0.768 | |||

| Television | 0.778 | |||

| Daily/Weekly Newspapers | 0.785 | |||

| Internet | 0.444 | |||

| Pollution | 0.731 | |||

| Climate change | 0.846 | |||

| High catches | 0.531 | |||

| Angler | 0.805 | |||

| Member of angler family | 0.720 | |||

| QUANTITATIVE VARIABLES | |||

| Variable | Description | Mean | SD |

| WTP-LIH | Continuous variable to indicate the WTP for product with LIH Label, € /Kg | 0.931 | 1.155 |

| WTP-BFG | Continuous variable to indicate the WTP for product with BFG Label, € /Kg | 1.19 | 1.434 |

| Age | Discrete variable, minimum value 18 years | 51.4 | 15.1 |

| Income | Continuous variable, € /month | 1732 | 657.249 |

| QUALITATIVE VARIABLES | |||

| Variable | Description | Proportion | |

| LIH | Dummy variable for LIH Label: 1 if present, 0 if not | 0.969 | |

| BFG | Dummy variable for BFG Label: 1 if present, 0 if not | 0.945 | |

| Gender | Dummy variable for male and female sex: 1 if female, 0 if male | 0.521 | |

| Income earners | Dummy variable: 1 if employed, 0 if not | 0.794 | |

| Family situation | Dummy variable: 1 if other family situation, 0 if living alone | 0.889 | |

| Contaminant limits | Dummy variable to indicate if contaminant limits is known: 1 if so, 0 if not | 0.659 | |

| Store | Dummy variable for store city: 1 if Milano, 0 if Palermo. | 0.425 | |

| Other eco-products | Dummy variable to indicate if other eco-products are bought: 1 if so, 0 if not | 0.43 | |

| Variables | LIH | BFG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Intercept | 2.6306 *** | 2.5460 *** | 1.0826 | 0.1225 |

| (0.7718) | (0.8155) | (0.6834) | (0.7551) | |

| Gender | −0.1407 | −0.1636 | 0.1721 | 0.2730 |

| (0.2505) | (0.2648) | (0.2366) | (0.2686) | |

| Age | −0.0091 | −0.0115 | 0.0035 | 0.0061 |

| (0.0080) | (0.0085) | (0.0073) | (0.0082) | |

| Income earners | −0.7774 *** | −0.7929 *** | 0.0595 | 0.1173 |

| (0.4450) | (0.4807) | (0.2654) | (0.3016) | |

| Income | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 *** | 0.0006 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | (0.0002) | |

| Family situation | 0.2951 | 0.3986 | −0.5351 | −0.5039 |

| (0.3171) | (0.3375) | (0.4783) | (0.5256) | |

| Means of technical communication (C1) | 0.1148 | 0.1063 | −0.0331 | −0.0307 |

| (0.1737) | (0.1793) | (0.0454) | (0.0525) | |

| Means of mass communication (C2) | −0.0597 | −0.0576 | −0.0409 | −0.0729 |

| (0.0763) | (0.0810) | (0.0670) | (0.0750) | |

| Attention to environmental features (C3) | 0.1182 | 0.1362 *** | 0.1503 *** | 0.1681 *** |

| (0.0762) | (0.0811) | (0.0677) | (0.07959) | |

| Angler community (C4) | 0.0625 | 0.0395 | 0.0003 | −0.0661 |

| (0.1001) | (0.1025) | (0.0782) | (0.0868) | |

| Contaminant limits | 0.0328 | 0.3880 | ||

| (0.2676) | (0.2583) | |||

| Store | −0.1549 | −0.1186 | ||

| (0.2686) | (0.2811) | |||

| Other eco-products | 0.3054 | 0.9843 *** | ||

| (0.2701) | (0.3375) | |||

| Null deviance | 135.29 | 129.71 | 175.30 | 164.76 |

| Residual deviance | 122.89 | 114.96 | 157.48 | 129.71 |

| AIC | 142.89 | 140.96 | 177.48 | 155.71 |

| Pseudo R2 (McFadden) | 0.1987 | 0.2377 | 0.2143 | 0.3006 |

| No of cases | 509 | 453 | 446 | 422 |

| Variables | WTP-LIH | WTP-BFG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Intercept | 5.8173 *** | 6.4480 *** | 6.9990 *** | 5.0615 *** | 5.0977 *** | 6.4760 *** |

| (0.4559) | (6.5820) | (0.5106) | (0.6690) | (0.9003) | (0.7582) | |

| Gender | 0.3606 ** | 0.3297 ** | 0.4738 ** | 0.4620 ** | ||

| (0.1771) | (0.1371) | (0.2295) | (0.1908) | |||

| Age | 0.0006 | −0.0063 | 0.0055 | −0.0028 | ||

| (0.0056) | (0.0044) | (0.0072) | (0.0060) | |||

| Income earners | −0.3563 * | −0.0034 | −0.3308 | 0.0638 | ||

| (0.2630) | (0.1723) | (0.2799) | (0.2353) | |||

| Income | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | ||

| (0.0001) | (0.0000) | (0.0001) | (0.0001) | |||

| Family situation | −0.6731 *** | −0.3028 | −0.5164 * | −0.2386 | ||

| (0.2560) | (0.1995) | (0.3138) | (0.2621) | |||

| Means of technical communication (C1) | 0.0514 | 0.0438 | 0.0081 | 0.0250 | 0.0301 | 0.0013 |

| (0.0368) | (0.0409) | (0.0317) | (0.0423) | (0.0445) | (0.0371) | |

| Means of mass communication (C2) | 0.2753 *** | 0.2669 *** | 0.1291 *** | 0.2961 *** | 0.3147 *** | 0.1510 *** |

| (0.0460) | (0.0529) | (0.0419) | (0.0606) | (0.0677) | (0.0580) | |

| Attention to environmental features (C3) | 0.1579 *** | 0.1178 * | 0.0764 * | 0.0995 | 0.0727 | 0.0948 |

| (0.0519) | (0.0611) | (0.0474) | (0.0702) | (0.0768) | (0.0639) | |

| Angler community (C4) | 0.1412 *** | 0.1821 *** | 0.1230 *** | 0.0990 | 0.1651 ** | 0.0787 |

| (0.0521) | (0.0583) | (0.0453) | (0.0684) | (0.0755) | (0.0632) | |

| Contaminant limits | −0.1370 | −0.0880 | −0.0815 | −0.0088 | ||

| (0.1735) | (0.1343) | (0.2184) | (0.1818) | |||

| Store | −2.1060 *** | −2.1850 *** | ||||

| (0.1371) | (0.1987) | |||||

| Other eco-products | −0.2582 | 0.0210 | −0.3178 | −0.0268 | ||

| (0.1639) | (0.1281) | (0.2130) | (0.1789) | |||

| Consumers’ awareness | 0.2772 | 0.4499 | 0.2791 | 1.4781 ** | 1.6027 ** | 0.6757 |

| (0.4618) | (0.4919) | (0.3809) | (0.6782) | (0.7006) | (0.5881) | |

| R-square (Adjusted) | 0.0995 | 0.1041 | 0.4635 | 0.0777 | 0.0963 | 0.3753 |

| No of cases | 454 | 364 | 364 | 350 | 307 | 307 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vitale, S.; Biondo, F.; Giosuè, C.; Bono, G.; Okpala, C.O.R.; Piazza, I.; Sprovieri, M.; Pipitone, V. Consumers’ Perception and Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Italian Hypermarkets. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041434

Vitale S, Biondo F, Giosuè C, Bono G, Okpala COR, Piazza I, Sprovieri M, Pipitone V. Consumers’ Perception and Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Italian Hypermarkets. Sustainability. 2020; 12(4):1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041434

Chicago/Turabian StyleVitale, Sergio, Federica Biondo, Cristina Giosuè, Gioacchino Bono, Charles Odilichukwu R. Okpala, Ignazio Piazza, Mario Sprovieri, and Vito Pipitone. 2020. "Consumers’ Perception and Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Italian Hypermarkets" Sustainability 12, no. 4: 1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041434

APA StyleVitale, S., Biondo, F., Giosuè, C., Bono, G., Okpala, C. O. R., Piazza, I., Sprovieri, M., & Pipitone, V. (2020). Consumers’ Perception and Willingness to Pay for Eco-Labeled Seafood in Italian Hypermarkets. Sustainability, 12(4), 1434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041434