Abstract

The present research paper analyses the EU general and mandatory sectoral legal framework on public procurement, arguing for its inhibiting effect on the EU-wide uptake of green public procurement. It explores de jure and de facto barriers to green public procurement, motivated by the need for a change in the business world towards more sustainable practices through preferably mandatory legal changes of EU corporate law. As the public procurement represents a strong nudge for a qualitative change in private market demand, accounting for a minimum of 12% of the national gross domestic product, it should become environmentally sustainable itself and guide markets through the qualitative and quantitative changes on the demand side. Given the complexity of the current legal framework and the novelty of the approach to public procurement as a strategic tool for the achievement of sustainable production and consumption, a better defined and clear legislative approach is called for, possibly in a mandatory form, clarifying the obligation of public procurers to account for sustainability in their practices, especially as regards incorporating environmental concerns in their purchasing activities. In its current form, the EU legislative public procurement framework entails a seemingly permissive attitude towards green public procurement, hampered in practice by the existing legal institutes in the field, which hamper the strategic use of public procurement and thereby its influence on sustainability on the private markets.

1. “Green” Public Spending as a Precondition for Mandating Business Sustainability? The Motivation

In 2050, we live well, within the planet’s ecological limits. Our prosperity and healthy environment stem from an innovative, circular economy where nothing is wasted and where natural resources are managed sustainably, and biodiversity is protected, valued and restored in ways that enhance our society’s resilience. Our low-carbon growth has long been decoupled from resource use, setting the pace for a safe and sustainable global society.EU’s seventh Environmental Action Programme (EAP)

The notion of sustainability has been increasingly used as a synonym for responsible business conduct, in academia as well as in the general population. The awareness of the importance of pertinent environmental, societal, and economic issues has been consistently growing [1]. The current global focus is on corporate sustainability, e.g., making corporations more resource-efficient and productive, while ensuring a minimum negative impact on nature and society and entailing the least possible negative economic implications for companies themselves. Such development is currently driven by voluntary corporate action beyond environmental law requirements [2] and by market demand [3,4], while corporate law is staying predominantly silent on the matter [5,6]. In the present moment, companies lack appropriate incentives to behave sustainably [7,8,9]. If such incentives are present, the market (at least in the short term) punishes sustainable behaviour [10]. To be able to impose mandatory corporate sustainable requirements, companies need to see such intervention as legitimate to internalise it and exhibit a high level of compliance [11], especially in light of the political pressure against such a change [12]. Governments themselves should use sustainable services and products, leading by example, to achieve sustainable development [13,14]. As public spending represents, on average, 12% of the gross domestic product in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (hereinafter: OECD) countries [15], 14% in Europe [16,17], and up to 30% of the GDP in developing countries [15], it entails substantial purchasing power and represents a tool for influencing private markets. Legally, regulating consumption is often not feasible due to various legal and practical reasons [18], and public procurement as one of the key governmental economic activities [19] could and should be used strategically to boost sustainable market demand [20,21,22]. While substantial scholarly attention has been given to considerations on the insertion of environmental concerns in public procurement practices [23], the EU legal framework, per se, as a matter of policy coherence and a disincentivising circumstance for sustainable procurement practices has received limited scholarly attention [24]. Although arguments for the need to mandate sustainable procurement practices has been present in the scholarship [25], they are of a more general nature and they have not addressed the legal uncertainty and complexity of the existing legal frameworks. The present work therefore aims to highlight the complex and interdependent nature of the EU freedoms and the public procurement legislation, especially the “link to subject matter” requirement that was developed by the Court of Justice and later inserted in EU legislation, negatively influencing the consideration of environmental conditions in public procurement across the EU.

Green public procurement (GPP), as in, “procuring goods, services, and works with a reduced environmental impact throughout their life cycle when compared to goods, services, and works with the same primary function that would otherwise be procured” [26] can create significant spill-over effects on the private market side [27,28,29], also by lowering the prices of sustainable products under economies of scope and scale. Its importance as an integral part of sustainable public procurement (SPP) lies in its potential to contribute to the mitigation of climate change through its reduced environmental impact, countering ‘business as usual’ and incentivising change on private markets to that effect. Focusing on GPP as the environmental component of SPP for the purposes of the present article serves the interest of building a strong, resilient GPP framework, which in itself ameliorates the social issues that will inevitably accompany the environmental systemic disruptions in the case of a non-mitigated climate change. SPP as a “process whereby public organizations meet their needs for goods, services, works, and utilities in a way that achieves value for money on a whole lifecycle basis in terms of generating benefits not only to the organization but also to society and the economy, whilst significantly reducing negative impacts on the environment [30]” entails not only environmental, but also social considerations. In the absence of broadly implemented GPP, adding social considerations into the public purchasing process on top of environmental considerations might arguably be counterproductive. It seems more reasonable to insert legal certainty and clarity in the process of GPP first, based on existing best practices, thereby incentivising sustainable consumption and legitimising a further governmental intervention in private markets, before embarking on a more ambitious path. Such reasoning is further supported by the urgency of action against climate change and the international EU’s legal obligations to that effect.

Building on the “nudging” influence of GPP, the present article presents the disincentivising role of the existing EU public procurement legal framework for exercising GPP and calls for a simplified or sectoral approach to GPP at the EU level, preferably in a mandatory form, as a legitimising precondition for an introduction of mandatory sustainable corporate law framework. Assuming that the EU objective of sustainable development strives to be achieved primarily through the encouragement of sustainable consumption and production [31], governments should not only serve as role-models, but also as pioneers in finding appropriate solutions for the collective action [32], information exchange [33,34], and monitoring problems [35] connected with the development of sustainable business practices in the form of GPP “best-practices”.

In terms of research design and methodology, an EU-wide desk research and analysis of secondary sources on the uptake of GPP will serve as the main methodological approach, coupled with a traditional legal analysis of primarily EU rules on public procurement. By providing a systematic overview of existing EU legislation on the matter, the complexity of applicable legal rules will be presented as a de jure barrier for GPP across the EU, that can be overcome by a refinement of the existing legal framework, providing additional legal certainty for national public officials, and serving as a stepping stone for mandatory legislation in the field. Coupled with the existing efforts of sharing best practices and educating procurers at the executive and managerial level, GPP becoming a mainstream activity can become a reality.

The approach of the paper is two-fold: firstly, it lays out the current legal complexity of GPP and discusses its role as an impediment to a higher uptake of GPP across Europe, and secondly, it provides suggestions for resolving the current challenges with the uptake of GPP in the form of mandatory changes to the general public procurement legislation at the EU level, building on examples of successful sectoral mandatory EU GPP rules.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 lays out the considerations on the nature of GPP and briefly discusses ways for environmental concerns to enter the public procurement procedure. Section 3 presents arguments for focusing on EU public procurement rules, while laying out the legal authority for GPP in the EU and discusses the complexity of the current legal framework. It argues that the existing legal rules are complex and cause legal uncertainty, which has an inhibiting effect on the uptake of GPP. Section 4 concludes and suggests a trajectory for further research on the matter.

2. The Nature of GPP—How Can Environmental Concerns Enter the Procurement Procedure?

The EU has been actively encouraging GPP since the year 2003 [36,37], also through legislative instruments [14,38], yet actual uptake of such procurement has not been linear [39]. In global terms, only 4% of the national governments have reached a fully integrated sustainable public procurement, coupled with monitoring and evaluation procedures, while 39% of national governments have provided SPP procedures for some products [40]. In the EU, the majority of EU Member States possessed a national GPP action plan by 2010 [41] (p.42), but GPP rarely reached beyond 40% of public procurement (in value) [41] (p.41). Previous research divided the EU Member States into two distinct groups: the “green seven” consisting of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Sweden, and a group containing other EU Member States [42]. In the EU, GPP is a voluntary exercise and has been mandated only through sectoral selection in the case of a few product groups [43,44,45,46,47,48]. The only EU country mandating a 100% GPP is the Netherlands [49].

While procuring sustainably is a possibility under EU law [38,50], allowing for the calculation of the most economically advantageous tender (MEAT) through the life-cycle cost and accompanying methods [51], such action is not obligatory, resulting in its modest uptake by EU national public administrations [16] (pp.5–6). Depending on the type of procurement, the procedural stages, including technical specifications, award criteria, labels, exclusion grounds, and the contractual conditions, public procurement can be used to create a positive effect on the environment.

Despite a relatively clear definition of GPP as a concept, the insertion of environmental concerns in public purchasing procedures ranges from a simple demand for a greener product to a holistic approach of integrating ‘green’ criteria into all steps of the procurement process [52]. While any effort, however small, adds to the final goal of sustainable production and consumption, the climate emergency calls for clear commitment to do at least as much as the existing legal frameworks allow. The current EU legal framework allows for the use of all variations between the two extremes named here above: from the sourcing of a product formulated with the use of green criteria, requiring in the call for tenders the use of green technology by the suppliers, seeking greener functionality—as in, sourcing a greener product, service, or works for meeting the identified needs, while achieving the best value—or as a holistic approach, greening the whole procurement process, integrating green criteria into all steps of the procurement process, including the contract performance stage, inserting requirements as to the products’ energy or water use. The procurement process can be presented with a simplified scheme, portrayed hereunder in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A simplified scheme of a public procurement procedure [53].

As the quality and success of a public procurement process depend on its design [54], the GPP procedure should start with carefully defining the public need as a pre-condition for the choice of the most appropriate form of the procurement procedure. This pre-tender, preparatory stage allows for a margin of discretion by public procurers that is broader than the one offered by the subsequent procurement stages [55]. As such, its use for the development of green solutions in public procurement has also been promoted by the EU Commission [56], yet the present article shies away from analysing the use of these procedures for spurring GPP uptake across the EU due to several reasons. Firstly, these procedures represent a relative novelty in EU public purchasing and their broad use represents a challenge on its own, which merits a discussion in a separate paper. Secondly, the present paper aims to analyse the current most commonly used public procurement procedures and the accompanying legal framework and its potential for facilitating a broader use of GPP. Thirdly, so-called public procurement of innovation and other dynamic pre-tender procedures’ utility for the exercise of GPP is limited in the sense that the public procurer needs to be aware of the environmental objective they are procuring in a particular case when calling for market solutions, which presupposes a significant level of knowledge and awareness of environmental impacts of sourced products, services, and works by the public procurer. Albeit briefly described as a legal possibility and a supporting GPP tool in Section 3.3.2, their full potential for GPP can only be reached when public procurers possess a certain level of knowledge on what the environmental concerns regarding particular purchases are. Fourthly, for GPP to become widely used, it should firstly enter the procedures public procurement professionals are familiar with and accustomed to, hence the traditional open tendering procedure and the insertion of environmental criteria in technical specifications, award criteria, and conditions of the execution of contract [57]. Lastly, for GPP to have a significant positive environmental impact, it has to be designed properly and executed in an appropriate manner [58]. As research has shown that the majority of EU Member States’ public procurement is carried out at the local or regional level [59], the departments and individuals carrying out the majority of the GPP have a limited capacity and knowledge to engage in innovative procurement procedures. Focusing on GPP implementation across the already established procedures might yield faster and better results, especially at the local and regional level, than proceeding at those levels with novel public procurement procedures. Therefore, the analysis of the legislation on subsequent phases of the public procurement procedures as an inhibition for a broader uptake of GPP might be more appropriate to provide an insight into the possibilities for further developments in the field.

At present, the GPP has been most commonly implemented at the stage of tender specifications and inserted in the award criteria of the tender processes, and has been often criticised due to insufficiently well-defined criteria [60]. This attests to the documented lack of expertise on the matter of public procurement [61] that has been noted in the scholarship. What is more, the modest use of GPP across Europe can further be attributed also to the risk-averse nature of public procurement officials, especially in light of the complex EU legal framework on the matter that also applies, by virtue of national transposition of directives, to purchases below the EU thresholds, in public procurement at the local and regional level [62]. The change in the nature of public procurement from an enabling instrument of the internal market into a strategic instrument for achieving EU policy objectives has resulted in a sometimes contradictory and complex legislative web that inhibits the transition towards GPP as a general European practice. The following section aspires to provide an insight into the complex nature of this legislation and its influence on the uptake of GPP across the EU.

3. Where Do We Stand? The State-of-the-Art and Legal Possibilities under the EU Law

3.1. Preliminary Remarks on the Focus on EU-Level Legal Framework

It could be argued that the uptake of GPP could be better tackled by legislating at the national, regional, or even local level. Yet, the EU GPP implementation results suggest that an overarching EU strategy and sharing of best practices under an umbrella framework is needed to achieve less fragmented results. By way of example, despite the EU Commission’s goal that 50% of EU-wide public procurement should be green by 2010 [63], the 2012 report on the uptake shows that the goal was not reached at the local, regional, or national level [64]. Certain jurisdictions exhibited high success as GPP leaders, while others struggled to insert environmental components in any of the procurement stages. To surpass these differences and insert a GPP level playing field while ensuring a significant impact of greening private markets, tackling large (in value and impact) procurement procedures regulated at the EU level represents an important centralised action that can drive further GPP changes at the national, regional, and local level, including in jurisdictions where the GPP is currently underdeveloped.

While the EU Member States can and should further their GPP efforts also in public procurement processes outside the scope of EU public procurement rules, the transformation of public procurement legal frameworks towards sustainability occurred only in isolated cases at the local, regional, and sometimes national level. This calls for a focus on EU legal rules on the matter and their possible influence on the EU Member States’ legislation and practices on the matter. To level out the disparities among EU Member States’ regulation of public procurement at different stages, a clear EU legal framework would represent a nudge in the right direction. This holds true especially for procurement processes falling under the Public Procurement Directives, with expected spill-over effects to other public procurement procedures that fall outside the scope of EU rules, once skills and competences of GPP under the mandatory EU framework are acquired. All in all, while national, regional, and local rules can be argued to have a more direct effect on local public procurers, those rules need to lead to coordinated sustainable outcomes, preferably in all 28 EU Member States, to represent a strong enough nudge for the private market towards sustainable business solutions.

3.2. Legal Authority—EU Green Procurement Policy

Environmental concerns have grown substantially in the last decade and have become a fundamental part of EU law. EU legislation has established more than 130 separate environmental targets and objectives to be met between 2010 and 2050 [65]. While at its roots [66], the EU environmental policy was meant to prevent diverse environmental standards resulting in trade barriers and competitive distortions in the internal market [67], today it plays a different, much more active and integrated role. Such a changed role is reinforced by Article 11 of the Treaty on the Functioning of European Union (TFEU) [68], setting a legal duty to integrate environmental protection requirements throughout the EU policies and activities [69].

Overall, achieving sustainable development is an EU priority, not only according to the Treaty provisions [70], but also according to the general principles of EU law [71]. There have been many EU action plans and policies developed to that effect [72,73,74], and many international obligations entered into by the EU [5], which do not only legitimise but also necessitate further EU internal action on the matter. Public procurement represents a special place in that quest; not only by its nature and size, but also since in the absence of action in this field, sustainable development cannot be properly achieved [75]. Given the arguably insufficient enabling legislation, further EU efforts towards a higher uptake of GPP are called for [24].

3.3. The Legal Uncertainty of EU Green Public Procurement

While in 2003 the EU Commission called for national GPP action, providing targets and concrete measures [63], and further set the aim of increasing the average level of GPP in the EU to the level of the best performing Member States in 2006, national implementation did not reach this objective [42], also due to the voluntary nature of the GPP [76]. There are many awareness-raising [77], toolkit development [78], and capacity-building activities [77] across the EU that seem to be overridden by de jure and de facto barriers to GPP. Some of these are the legal risk such procurement entails in the eyes of risk-averse and less entrepreneurial public procurement organisations and their practitioners [61,79], the lack of knowledge [80], and the lack of political and practical guidance on the matter for public officials [80] (pp.319–320). Furthermore, the often single-year budgeting of public expenditure discriminates against products with lower life-cycle costs but higher upfront costs [61] (p.9), as it inhibits officers from accounting for life-cycle savings of products or services purchased under the MEAT method.

In terms of the EU legislation, the door to environmentally friendly public procurement opened in 2004 with the Public Procurement Directives [81,82] to the exclusion of the utilities sector. These directives were further amended in 2014 to stimulate the demand for innovative and green products and tackle the issue of legal uncertainty for public procurers [38,79]. As seen in the previous paragraph, even new legislation on the matter did not significantly influence the uptake of GPP across the EU. Reasons for this are multi-fold and can be divided into two groups: the de jure group, or the risk of the illegality of a particular use of GPP, and the de facto group, or the expertise deficit of public procurers on the matter. While both of these can be tackled by similar public and private tools, the applicable legal framework needs to provide legal certainty as to the use of environmental concerns in public purchasing.

3.3.1. The Inherent Legal Risks of the General EU Legal Framework

The EU has historically identified public procurement as a significant non-tariff barrier to trade [83]. The early EU regulation on the matter aimed at regulating public markets to reduce the possibility of states using public procurement in a way that is not compatible with the internal market objective [84]. Such an approach is primarily reflected in the application of the general principles of EU law and the TFEU provisions on the free movement of goods, freedom to provide services, and freedom of establishment [38] (Recital 1). These provisions bear heavily on the formulation of environmental criteria in public procurement and insert additional compliance risk, even in the best-case scenario, where the authority in question masters secondary EU legislation on the matter and the formulation of environmental criteria that are to be inserted in public tenders. In the following subsections, the application of the three EU freedoms will be elaborated on in the framework of GPP to illustrate the extent of legal risk that procuring green currently entails, thereby disincentivising public authorities to engage in GPP.

The principle of free movement of goods [85] implies that contracting authorities engaging in GPP must formulate environmental criterion in a way that it does not (in)directly discriminate between domestic and imported goods, nor include a specification on product characteristics that would hinder trade. In practice, this translates into a requirement of allowing the tenderers to comply not only with domestic but also with equivalent foreign environmental standards [38] (Recital 1). Environmental concerns represent a justified derogation from the free movement of goods [86], inasmuch as such a measure does not confer an unrestricted freedom of choice on the contracting authority. This condition is subject to interpretation and represents a source of legal risk for the procuring authority. While environmental protection has been acknowledged by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) as a mandatory requirement justifying derogations from the freedom of movement of goods, there is an additional requirement of proportionality of the restriction to the goal to be attained [87]. Judging the proportionality of the measure in question might appear to be excessively risky for public procurers, who then resort to business as usual, e.g., procuring based on the lowest upfront costs.

Similar to the free movement of goods, freedom to provide services [88] in the case of GPP demands that contracting authorities ensure that any requirement posed by a tender does not restrict access to service markets for foreign tenderers. This freedom can be derogated from on the grounds of public policy, morality, or security (hence entailing environmental concerns) [89] and as a justified mandatory requirement formulated by the CJEU. As in the case of free movement of goods, under the freedom to provide services, a similar disincentivising effect of these provisions for engagement in GPP can be discerned: it is simply easier to omit the environmental conditions altogether. For both products and services, the Treaty freedoms limit the scope for the public procurer’s consideration of other environmentally material characteristics of the purchase as a whole, e.g., its environmental costs of transport and packaging, which can potentially be determined as discriminatory under the free movement of goods and the freedom to provide services.

While freedom of establishment [90] does not represent an issue connected exclusively to GPP practices, it is worth noting that access to national tenders needs to be open to people established in other Member States than the state of the tender in question; e.g., foreign individuals and legal entities cannot be restricted from accessing public contracts [91]. While this is a general requirement to be accounted for in public procurement procedures, it might pose an additional barrier for implementing GPP, as supply chains and compliance with environmental requirements are already difficult to trace in a national setting. Furthermore, considering environmental impact in public procurement might result in indirect discrimination of foreign enterprises. By way of example, transportation costs might be decisive in awarding the public contract to the detriment of foreign companies.

Aside from these TFEU provisions, the general principles of EU law add to the complexity of legal requirements for GPP. As these principles have been given constitutional status [92] and take precedence of both secondary law and international agreements signed by the EU, they need to be given full effect in legal areas governed by EU law. The principles of equal treatment [93], non-discrimination [94], transparency [95], proportionality [96], and mutual recognition [97] are of particular importance to public procurement. Their application to the already uncertain formulation of environmental criteria in public procurement processes adds to the inherent legal risks of engaging in GPP. This is not to say that this obstacle is unsurmountable, but rather that a legal clarification on the application of these freedoms and general principles in the framework of GPP would be advisable.

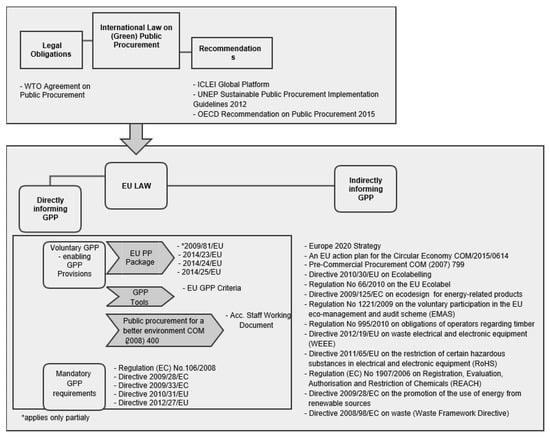

Next, to the complex and, at times, difficult to manage web of secondary EU law, as depicted in Figure 2, the application of TFEU freedoms and general principles of EU law adds to the perceived riskiness of procuring green. Environmental requirements or conditions determined by public authority might result in being unintentionally discriminatory or unequal, thereby representing a serious risk of non-compliance, further disincentivising public officials from engaging in GPP practices in the first place. This argument is supported by the fact that the provisions of the procurement directives and TFEU bear direct effect in the EU Member States, regardless of their transposition in national law [98].

Figure 2.

The current mandatory and voluntary legislative framework on green public procurement.

Environmentally friendly procurement allows for tolerating a certain financial disadvantage in light of the environmental objective to be attained, and it thereby opens the door for worsening institutional quality and a possible fall in the transparency of procurement processes [99]. As the pursuit of environmental objectives in public procurement needs to be in line with the general EU law, this adds to the complexity of the legal limitations that public officials are facing. This complexity negatively affects the use of GPP in practice, as it entails substantial and diverse legal risks. In other words, if the public official in question is not only unsure how to determine environmental conditions, but also how to do so in compliance with the EU or implementing national law(s), they will not procure green. As authorities are not obliged to procure green and as procuring green does not entail any personal benefits for them, public procurement according to the lowest price prevails, without accounting for environmental impacts. This is a development that has occurred across the EU regarding the uptake of GPP, contrary to the EU aims and expectations.

3.3.2. Public Procurement Directives as a Source of Legal Uncertainty

Allowing for the insertion of environmental criteria in EU public procurement processes represents an important amelioration of public purchasing, especially as such considerations were historically seen as an interference with the internal market objective. The opening of this possibility has also brought about significant legal uncertainty as to how to proceed regarding this option for the public procurers in practice. In practice, the actual uptake of GPP has also been modest due to the risk-aversion of public procurement officers and the need for some entrepreneurial skills of the responsible procurer to engage in GPP [15].

To engage in truly environmentally sustainable public procurement, additional preliminary steps need to be undertaken that differ from the traditional public procurement processes. The most environmentally sustainable decision is not to purchase a good at all, but if an objective need is established that cannot be satisfied by the already existing products, service, or works contracts, then the public procurer should explore alternative, circular means of satisfying the identified need. There needs to be a rising awareness of the circular possibilities at public procurers’ disposal, e.g., leasing a product instead of buying it [15] (pp.43–44). Only after such considerations have been accounted for and explored, should the option of GPP be explored.

At this stage, and considering that the markets of environmentally friendly products, services, and/or works are still developing, there is a possibility that the needed purchase with desired environmental effects will not be available on the market. In that case, the EU legislation encourages public officers to use one of the alternative public procurement procedures. Especially pertinent in the case of GPP is the competitive procedure with negotiation and competitive dialogue, as it allows for the adaptation of existing market solutions in search of the most environmentally friendly option [38] (Article 26(4)). Here, the procuring authority and private market actors co-create the tender specifications, jointly building the solution to the environmental issue. Similarly, innovation partnership allows for research and development to enter the public purchasing procedure by establishing a structured partnership, allowing for piloting and subsequent purchase of the developed product, service, or work [38] (Article 31). Furthermore, the EU law conditionally allows for pre-commercial procurement [38] (Article 14), where no solution exists on the market that could fulfil the environmental conditions desired. Pre-commercial procurement allows for procuring research and development services that help to identify the most appropriate solution through progressively identifying the best potential solutions, followed by procuring the final product, service, and/or work through the regular public procurement procedures. While these options are very valuable for the progress of GPP, by themselves they demand a certain level of expertise and knowledge on their use, as briefly discussed in Section 2. For this reason, a more thorough debate on their use as a tool towards a global GPP tool is not provided in this paper, as its focus lies in using the procurement procedures public procurers are familiar with, with the main variable of determining the nature and characteristics of the environmentally friendly product, service, and/or work. The following sections focus on the steps of GPP taken when using the traditional open or restricted public procurement procedure.

Aside from these novel procedures, the procuring authority traditionally used four distinct procedures. In the case of GPP, they can engage in an open procedure, inviting a broad spectrum of environmentally friendly solutions or restrict the procedure to only those suppliers who satisfy the environmental technical capacity determined by the authority. While the former option allows for a wider scope of environmentally friendly solutions, the latter demands a certain level of GPP expertise in determining the environmental technical capacity of the supplier in question. Furthermore, in the light of the need for flexibility and novel solutions, the procedures of competitive dialogue and competitive procedure with negotiations allow for adaptation of the products and services to the necessities of the purchasing authority in question. The decision for one of those procedures will, therefore, depend on the expertise of the procurer in question as well as the existence of environmental information on this particular product, service and/or work.

In the framework of public procurement, combining economic and environmental considerations while purchasing goods or services is of utmost importance in the context of providing value for money to taxpayers. While there is a consensus in sustainable supply management literature on the need for the effective integration of the economic, environmental, and social considerations in the purchasing procedure [100], in terms of public procurement, there seems to be a lack of certainty as to what kind of balance is allowed under the existing legal rules. Hence, the specific legal framework of public purchasing further hinders the already delicate exercise of striking the right balance between the triple sustainability concerns. Furthermore, as GPP calls for a dynamic relationship between the suppliers and the sourcing authority in the context of the developing green products and services market, the enabling legal framework needs to be constructed in a way provides tangible environmental results, without which GPP cannot be used as a strategic tool towards sustainability.

Under the current legal framework, when a public procurer determines a need for purchase that falls under the scope of Public Procurement Directives [38] (Recital 1, Article 2(1)(1)), the EU legislation on the matter demands clarity on the inserted environmental conditions already at the stage of defining the subject matter of the earliest procurement document [38] (Article 2(13)). For administrations which are new to the use of environmental considerations, this task is challenging, to say the least, especially in light of the above-mentioned legal risks. Although the existing EU GPP criteria offer guidance for particular types of products and services [101], such guidance has not been sufficient to spur a high uptake of GPP processes across the EU, suggesting that further incentivising engagement in such strategic use of public procurement is needed. The EU-wide GPP uptake has indeed been very fragmented, with the top four performers having an uptake up to 60% and 12 Member States having an uptake of less than 20% [41]. As these guidelines provide general guidance and no assurance as to legal compliance when these criteria are inserted into actual procurement processes, the practitioners seem reluctant to use them. While these guidelines represent a great starting point to learn more about life-cycle thinking, their general nature and the form in which the information is provided impede their use in practice. By way of example, if an energy consumption limitation of purchased goods has not been communicated by the leadership to the procurer as a clear quantified goal, avoiding the insertion of these considerations in the purchasing procedure becomes the obvious choice in the absence of a legal obligation to that effect.

As to the selection stage, beyond the exclusion criteria [38] (Articles 18 and 54, Annex X), the procurers’ discretion is limited to the selection of economic operators on the grounds listed in the Public Procurement Directive: their financial standing, technical capacity, and criteria on the personal situation of the tenderer (e.g., professional honesty, solvency, reliability of the tenderer, and the requirement to be enrolled in certain trade or professional registers in their state of establishment) [38] (Article 58, Annex XII). This “pre-qualification” stage allows for a single green requirement of bidders, demonstrating their ability to carry out the contract in a sustainable manner, if, and only if, this is proportionate to the technical specifications of the contract [15] (p.55).

The judgment as to what is proportionate to the technical specifications of the contract again represents a substantial legal risk, as witnessed also in the EU case law on the matter [102]. The approach should be tailored to the specific requirements of the contract, including its value and the level of environmental risk involved, which offers little further guidance on the matter. Further limitation of scope is imposed by Annex XII, setting out the only types of evidence which can be requested in respect of selection criteria, including reference to previous work, technical expertise, environmental management measures, and also supply chain management and tracking systems [38] (Article 60(1)(4)). As to the certificates presented under environmental management systems, contracting authorities need to verify that they relate to the specific activity or activities which the contract concerns, a demanding task in light of the systemic nature of sustainability concerns and the trade-offs that being environmentally friendly entails. Even if contracting authorities successfully overcome the initial hurdle of determining basic environmental considerations, determining technical specifications [38] (Article 42) as a translation of the contractual subject matter into concrete and measurable requirements brings about further (legal) uncertainty. While this stage allows for a variety of options, a GPP-unskilled public official might find it overwhelming to determine the exact sustainability criteria that may translate into economic surplus under the life-cycle costing method of awarding a tender. Technical specifications may include sustainability concerns relating to sustainability impacts at any stage of the life cycle of a product, not limited to the finished product [38] (Article 42(3)). They can be formulated in terms of performance or functional requirements, including environmental characteristics, or by reference to standards, common technical specifications or references, or by a combination of these approaches [38] (Article 42(3)). Such a broad array of possibilities for public authorities to determine the characteristics of the sought sustainable purchase should facilitate the inclusion of such requirements in public purchasing processes, especially where supported by practical examples [15] (pp.57–62). Yet, public authorities have not used them as a common practice across the EU [81] (pp.319–320), [84], [103] (p.9). While a detailed debate on a non-discriminatory use of labels in the technical specification stage of tender surpasses the scope of the present article [15] (pp.59–62], it is worth noting that the use of labels in public purchasing is accompanied by stringent requirements that need to be further verified in the award of the contract stage. By way of example, when demanding Label X certification, other labels that demonstrate compliance with the same or very similar criteria must be accepted if they fulfil some requirements. They need to be verifiable and non-discriminatory; established using an open and transparent procedure, in which all relevant stakeholders (government bodies, consumers, social partners, manufacturers, distributors, and non-governmental organisations) may participate; accessible to all interested parties; and set by a third party, over which the economic operator applying for the label cannot exercise a decisive influence. If the tenderer can demonstrate that it had no possibility of obtaining the specific or an equivalent label within the time limits, for reasons not attributable to themselves, alternative proof needs to be accepted, such as a technical dossier. Furthermore, where the underlying criteria of a label also include criteria that are not specific to the product or service being purchased (i.e., not directly linked to the subject matter of the contract), the label may not be required. Hence, while using the so-called eco-labels might aid public officials in determining the kind of products, services, and/or works they are interested in in terms of their environmental impact, this short overview of the restrictions applied to their use paints a different picture: the legal uncertainty in the case of their use might arguably be higher than in the case of their absence.

At the award stage, specific award criteria need to be determined for bids fulfilling the technical specifications required in the call and can be determined as a mix of cost and quality criteria [15] (p.62). Environmental, social, and innovation characteristics may be accounted for in the quality evaluation of bids [38] (Article 67), not just as a pass/fail exercise as in technical specifications, but rather as progressively rewarding better performance or awarding points when specific thresholds are reached or specific conditions are met. While the traditional tool for choosing the most suitable tender, e.g., deciding on the basis of the lowest upfront cost of the contract, often does not allow for the greenest or the most sustainable products to be purchased [38] (Article 67(2)), the possibility of using the overall cost-effectiveness as the decisive factor (MEAT) and the connected life-cycle costing allows, but not mandates, greener or more sustainable choices to be made [38] (Article 68). While the EU law does not oblige the public procurers to acquire a product, service, and/or works with the lowest upfront cost, this option remains the default option in public procurement, arguably due to the ease of use of this criterion as compared to the overall cost-effectiveness mechanism.

Adding to the complexity of the entire legal framework is the “link to the subject matter of the contract”, developed in the Concordia Case [102] and inserted by the Public Procurement Directives in all procurement phases, aside from the qualifications. Link to subject matter is therefore required regarding technical specifications, labels, variants, award criteria, and contract performance conditions [103]. In Concordia, the CJEU allowed for the insertion of environmental criteria in the award criteria for public contracts:

The Court’s attempt to reconcile the contradictory objectives of non-discrimination of economic operators and the new strategic role of public procurement resulted in the use of “link to subject matter” across the public procurement procedure, further limiting the use of GPP, adding to the legal complexity of the GPP process as compared to the “traditional” procurement process. While referring to a sustainable business model of the supplier would make the GPP process easier for the procurer to some extent, under the “link to subject matter”, such practice is not allowed. Its ambiguous nature, as it is identified broadly and loosely, adds to the legal uncertainty of engaging in GPP and it has been suggested this be abandoned in favour of the use of life-cycle cost thinking [105]. Indeed, such a substantive change would lessen the legal uncertainty, while still providing sufficient protection from arbitrary decision-making, as the life-cycle costing has to be substantiated and proven [38] (Article43(1)(b), Article 44). Furthermore, the “objectivity criterion” of Public Procurement Directive [38] (Article 53(1)) as clarified by the CJEU in the EVN Wienstrom case [106] protects the equality of tenderers when they tender and when their tenders are being assessed by the contracting authority, calling for verifiability of the accuracy of information supplied by the tenderers, providing an additional layer of objectivity in the exercise of GPP. As the policy objectives of public procurement changed from ensuring fair competition and non-discrimination of tenderers while ensuring best value for taxpayers’ money to serving the public need for sustainable development and climate change mitigation, so should the “link to subject matter” requirement give way to objectively construed life-cycle costing.Provided that they are linked to the subject-matter of the contract, do not confer an unrestricted freedom of choice on the authority, are expressly mentioned in the contract documents or the tender notice, and comply with all the fundamental principles of Community law, in particular, the principle of non-discrimination—[104] (Paragraph 64).

Given the sustainability challenges the private markets are currently facing, the “link to subject matter” requirement can severely impede the positive environmental impact of GPP if used under the current EU legal framework. While in its current form the “link to subject matter” allows for sourcing a product of a particular origin [107] or produced by a particular method, environmental sustainability requires accounting for the environmental impact of the product as a whole, not only as regards its production, but also in terms of its design, transport, reparability, upcyclability, and the ease of its reuse and/or recycling [108]. A truly sustainable product needs to be able to be recycled, reused, reduced, or repurposed after it has served its intended purpose [109]. It should also be made from a renewable source or by using renewable energy to truly minimise its environmental impact. Last but not least, its carbon footprint should be accounted for. While these considerations can enter the public procurement process at several stages in the form of life-cycle costing, the implementation of GPP would be facilitated by suppliers guaranteeing such supreme environmental performance via their sustainable business models [110]. Yet, accounting for the overall environmental impact of the supplier through their business model is not allowed under the “link to subject matter” condition, which lowers the total positive environmental impact of GPP. If substituted with life-cycle costing, these considerations can enter the public procurement procedure, as the “life-cycle” has been defined as follows [38] (Article 3(20)):

“Life cycle” means all consecutive and/or interlinked stages, including research and development to be carried out, production, trading and its conditions, transport, use and maintenance, throughout the existence of the product or the works or the provision of the service, from raw material acquisition or generation of resources to disposal, clearance, and end of service or utilisation.

The following figure summarises the difficulties encountered by a public officer while determining the substance of a particular tender under the existing legal framework, not accounting for the additional complexity posed by the use of overarching EU legal principles, “link to subject matter” requirement and for specific national, regional, and local public procurement regulation:

3.3.3. The Experience with Mandatory Sectoral GPP Rules

As a comparative exercise, the experiences with Regulation (EC) No.106/2008 [111], Directive 2009/33/EC [43], Directive 2010/31/EU [44], and the Directive 2012/27/EU [46] as mandatory sectoral GPP instruments are analysed in the present section, with a two-fold purpose. Firstly, to discern whether a mandatory approach to GPP yields better results as to the implementation of such practices with a tangible environmental impact, and secondly, if the mandatory sectoral rules bring about more legal certainty than the general rules contained in the Public Procurement Directives. The initial hypothesis would be that these measures, where mandatory, significantly reduced the negative environmental impacts of corresponding sectors in a timeframe that would not have been reached under solely enabling legal instruments. Although the flexibility of “allowing” instead of “mandating” the insertion of environmental concerns welcomes new developments in GPP, the risk-averse nature of public procurers and the insufficient knowledge on the use of green options under the current complex legal framework severely impedes this innovation potential. Despite this somewhat hypothetical exercise of determining what would have happened if there was no mandatory legislation in the field, it is plausible to presume that under the existing evidence on the functioning, barriers, and facilitators of innovation in public procurement [64] changes would not have taken place in such a fast and unified manner.

Regulation (EC) 106/2008 was the first mandatory GPP legal instrument at the EU level, building on the US developed Energy Star requirements concerning the eco-labelling of office equipment, introducing mandatory public procurement standards for IT services. Similarly, later on, Article 9 of the Energy Consumption Labelling Directive 2010/30/EU allowed for tendering only for products with the highest performance level and the best energy efficiency class. While it is important to analyse the impact of these mandatory rules, an initial disclaimer on the current importance of the office equipment sector and its energy efficiency is due. Today, office equipment arguably holds a less dominant role in the total share of energy use, compared to several other consumer electronics, information and communication technology products, and telecommunications with “big data” infrastructure (i.e., “the cloud”). As the production of electronic and office automation products moved almost completely to Asia, the remanufacturing, repair, and recycling are creating alternative job opportunities and reducing imports of precious or rare materials. The resource efficiency and durability have gained far more relevance, which were not covered by the Energy Star programme [64]. It is reasonable to believe that under current market developments, the same regulation would not have been as successful. As to the impact of this regulation, it is not clear whether or not an impact assessment was carried out (preliminary or post ipso facto) [112,113], although it can be deduced from the information available that the impact of the regulation in the time of massive acquisition of information technology (hereinafter: IT) equipment was substantial, guiding the public authorities to procure more energy-efficient IT products [114]. In the absence of a detailed study, the real impact of the provisions of this directive cannot be directly discerned. Furthermore, as today the main concern regarding IT equipment does not lie in its energy efficiency, arguably also due to the results achieved by Regulation 106/2008, other tools for the mitigation of the negative impact of such equipment at the end of its life-cycle were enacted. One of these is the Directive 2011/65/EU [115], showing the changing needs with regard to the environmental demands and the products purchased through public procedures. To sum up, while the exact quantified effects of Regulation (EC) 106/2008 remain unknown, it has brought awareness to the public sector on the energy consumption of its IT goods and served as a stepping-stone for further mandatory developments in public procurement.

A year after the Energy Efficiency Regulation, the EU enacted a directive regulating the public procurement of vehicles. Directive 2009/33/EC [43] introduced environmentally-friendly vehicles into public procurement, requiring that energy-consumption and environmental impacts linked to the operation of vehicles over their whole lifetime are accounted for in all purchases of road transport vehicles [43] (Article 5). Contrary to the expectations, its implementation brought, at times, conflicting results of authorities opting for a diesel option of a vehicle, achieving insufficient trade-off between cleaner air and energy efficiency under the monetisation methodology, e.g., portraying the difference between “a cleaner and more efficient vehicle” and “a cleaner vehicle” [116]. The Monitoring Report of the Directive 2009/33/EC [115] showed that the actual implementation of the directive provisions depended on the policy priority of the entity that is procuring the product, service, and/or works [114] (pp.56–57), which in turn influenced the positive environmental impact of the Directive in question. The report laid out the inherent shift in perspective that is needed when evolving from the traditional price-focused public procurement towards environmentally sustainable public procurement under the MEAT criteria, where the life-cycle cost of the product in question should prevail. While public expense savings in public procurement on the basis of the lowest upfront costs are easily monetised, savings achieved through a public purchase of the most energy-efficient and environmentally-friendly product, service, and/or works are difficult to measure in terms of monetary savings and the environmental impacts, at least in the short run, as the benefits are not immediately evident [113]. The hands-on economic benefits calculation will not work with implementing GPP, once again portraying the need for a systemic and not solely a sectoral change. Accounting for the findings of the Monitoring report [115] (Recital 2), an amending Directive 2019/1161 [116] has been enacted in 2019, adopting a mandatory approach towards GPP in the form of clear, long-term procurement targets to “[…] trigger a market uptake of clean vehicles across the Union[…]” [116] (Recital 11). By extending the scope of Directive 2009/33/EC to lease, rental and hire-purchase of vehicles [116] (Recital 12), the amendment accounts also for the positive sustainable impact of circular economy practices of exchanging ownership for alternative forms of use, while simultaneously accounting for the market maturity when determining mandatory requirements [117] (Recital 16, 17). The amending Directive suggests that a mandatory approach is preferable, but it has to be adapted to the products, services and/or works as well as the market in question. The experience with recently amended Directive 2009/33/EC also attests to the need for continuous improvement and refining of the mandatory approach towards GPP, while reaffirming the argument that a mandatory approach is preferable for achieving sustainable results.

Further mandatory requirements regarding energy efficiency were developed at the EU level in the year 2010. Due to its size, the European market for energy efficiency in buildings was a logical sector for mandating further EU-level GPP requirements. This particular market represents around 120 billion EUR of the overall 500 billion EUR EU market for building renovation and the 400 billion EUR EU annual market for new construction [117]. Directive 2010/31/EU requires from the EU Member States that after 31 December 2017, all new buildings occupied and owned by public authorities need to be nearly zero-energy buildings [44,118] (Article 9). As this requirement came into force rather recently, the impact of this particular provision is yet to be measured, although without a doubt it minimises the environmental impact of every new building acquired or built for the needs of public authorities by the sole fact that it demands at least “a nearly zero-energy building”, e.g., a building with zero net energy consumption, where the total amount of energy used by the building on an annual basis is equal to the amount of renewable energy created on the site [119]. As to the effect of other provisions of Directive 2010/31/EU, the impact evaluation speaks of the achievement of particular goals of creating a demand-driven market for energy-efficient buildings (through certification and inspection), of setting minimum building energy performance requirements at cost-optimal level and preventing sub-optimal investments, and catalysing the increase in energy performance of buildings and the transition to nearly zero-energy buildings with diverse measures [120]. There is evidence of around 48.9 Mtoe (million tonnes of oil equivalent) of additional final energy savings in 2014 in buildings compared to the 2007 baseline of Energy Performance of Buildings Directive [38], occurring mainly within the scope of the said directive as a direct attribution to policy interventions [121] (p.10ff). This finding is in line with the 2008 Impact Assessment estimation of 60 to 80 Mtoe of final energy savings by 2020 [117]. The evaluation has shown that the mandatory certification of energy performance of buildings is encouraging consumers to buy or rent more energy-efficient buildings; a demand-driven market signal for energy efficient buildings. In the absence of such information, the consumer would be left uninformed and incapable of making an environmentally sustainable decision, and hence unable to contribute to sustainable development. Although mandatory certification is a step in the right direction, the national certification control systems need to develop faster, with a focus on their usefulness and comparability, coupled with providing high-quality data on the energy performance of buildings [121,122].

In the year 2012, Directive 2012/27/EU furthered the EU aim to reach its 20% energy efficiency target by 2020, by demanding a more efficient use of energy from the EU Member States at all stages of the energy chain, from production to the final consumption. In Article 6, the Directive requires the EU Member States to ensure that central governments purchase only products, services, and buildings with high energy-efficiency performance, indicating what these items are and what level of performance they must meet [46,118], and to carry out yearly energy efficient renovations on at least 3% (by floor area) of the buildings they own and occupy. This was not expected to lead to especially high energy savings (approximately 9 Mtoe), but it was envisaged as a measure of high visibility in public life. In monetary terms, the benefits of this option were expected to outweigh the costs: additional energy-related investments of €1.6 billion per year between 2010 and 2020 were to be offset by savings on energy bills of €1.92 billion. This represents a general pattern in greening either public or private purchasing: the initial investment has repeatedly been argued as providing more benefits than costs in financial terms, too.

The Article 6 obligation is subject to several conditions listed in Article 6(1) and it applies only to contracts with a value equal to, or greater than, the thresholds laid down in the Public Procurement Directives [38] (Articles 4–6). Article 6 furthermore includes specific provisions on contracts of armed forces, assistance to regional and local administrative levels, promoting energy performance contracting and purchasing product packages. To assist public officers in implementing this article, also in light of its relationship with the Public Procurement Directives and its comparison with other EU legislation in the field of procurement and energy efficiency, the accompanying guidelines detail the procurement items and contracts to which it applies [118]. Public consultation on the review of this directive showed that 42% of the participating stakeholders believed that national guidance on the accurate characterisation of energy efficient products, services, and buildings is insufficient, while 53% of the participants called for procurement rules to also apply to public bodies at regional and local levels [123]. All these arguments support the general idea of the present article, where 52% of the participants shared the view that all EU public procurement rules relating to sustainability should be gathered under a single EU guidance framework. Several participants argued that public procurement rules would not be necessary if life-cycle cost savings were correctly factored in by the authorities [124]. While it was expected that the policy inherent in the Directive 2012/27/EU was capable of reaching the 20% energy savings objective and reaping the additional benefits that remain tangible beyond 2020 [125], the results depended on the year of measurement [126] and the country in question, but they were close to the targets set [126].

This brief analysis of EU legal instruments entailing mandatory legal GPP requirements portrays positive results that can be achieved in a relatively short timeframe, but also issues that arise with implementing mandatory solutions, particularly unexpected negative spill-over effects that one can expect with the implementation of a mandatory GPP framework. The impact of mandatory legislation seems to be two-fold: it incentivises further market developments in providing environmentally-friendly solutions, and provides a strong and efficient incentive for public procurers to engage in GPP. Despite the fact that the implementation of GPP under a mandatory framework has not been perfect, it caused the practices in the respective fields to significantly shift from business-as-usual towards understanding and accounting for environmental impacts in the public purchasing practices.

4. The Way Forward: Leadership, Clarification and Incentivising Mandatory Approach

In light of EU’s international obligations [127] and its internal aims and policies [102], it might be seen as illegitimate to continue to allow for the choice of the tender with the lowest price, without accounting for environmental concerns at any of the tendering stages. A qualitative change should occur, from allowing for the environmental considerations to enter the assessment of the overall cost of the product/service/works to demanding such considerations be included in the calculation of the total cost [128,129]. As sustainable behaviour surpassed the value-added stage for businesses and became a risk-mitigation exercise [130,131], environmentally sustainable procurement by governments should no longer be seen as a voluntary exercise, but rather as an obligation in line with the EU’s sustainability policies and international legal obligations.

The legal complexity of public procurement regulation, coupled with insufficient knowledge and experience of public procurers in the field of GPP and their non-entrepreneurial attitude, hinders engagement in green practices, especially as this engagement remains voluntary. While there is a vast array of EU guidelines on the matter and collections of best practices by individual procurement authorities and associations such as Procura+ [132] and GPP4Growth [81], public authorities seem to struggle with their practical use. Sectoral expertise is currently decentralised across the EU, and while GPP objectives are determined in a political sense, it is still up to contracting authorities as to how to formulate the environmental criteria, if they decide to use them, which is a complex and technically demanding exercise.

Public procurers themselves highlighted the lack of knowledge on determining the environmental criteria in the contract notice and on the development of the weighing system [81] (pp.319–320), especially in EU jurisdictions that have not been sustainable procurement leaders [133]. Despite the existing public and private tools and aids [103,134,135] for the process of GPP, there seems to be a mismatch between the existing knowledge and the uptake of GPP across the EU. The low uptake is not a result of an objective lack of knowledge on the matter, but rather of the fact that this knowledge is sectoral and geographically conditioned, and thereby fragmented (partially due to the language barrier and the specificities of national legal systems). Furthermore, public–private partnerships to this effect are possible and welcome, further supported by the framework of the flexible procurement processes, which is currently not widely used across the EU, to create additional synergies [136].

It is important to note that the change in public procurement policies presupposes more than just a simplification of the existing legal frameworks or mandating GPP. GPP presupposes first and foremost the existence of fundamentals: the principles, core subjects, considerations, and drivers. These fundamentals need to be supported by policy and strategy, presupposing leadership and accountability, appropriate implementation, alignment with organisational goals, and understanding the supply chains and (at least) environmental consideration in the supply chain. If the leadership is not established, or a clear governance system for GPP, empowering and training people, then the efforts of mandating GPP will be impeded. Priorities need to be made clear at the leadership level and inserted in the procurement systems so that planning can take place and the integration of environmental sustainability into the tender specifications becomes a policy priority, incentivising the public procurers to seek further guidance on the “how” part of the procurement processes. The credible commitment of leadership can be assured by mandatory legislative approaches, as shown by the mandatory sectoral approaches presented here in Section 3.3.3.

Building further on the analysis of the existing mandatory legislation above, in Section 3.3.3, mandatory GPP promotes the availability of information on the market, further standardisation, and more legally certain and efficient procurement processes for the authorities [137,138]. Furthermore, a mandatory GPP approach is likely to increase market demand and innovation and lower the costs of environmentally-friendly products and services. While the discussion on the exact form of this mandatory change surpasses the scope of the present work, the present paragraph suggests a few possibilities, ranging from a limited sectoral approach to a complete overhaul of the EU Public Procurement Directives. One possibility would be introducing mandatory targets by the EU legislature, demanding a certain percentage of public procurement to be green, with a phase-in provision requiring 100% at a certain date. While Sweden successfully implemented this approach, achieving 70% of its governmental tender offers, including environmental considerations by the year 2013 [137], the Netherlands struggled with achieving 100% SPP by 2010 (at the local level by2015) [138], where Dutch public procurers suggested a move away from targets towards a process-oriented mandatory approach.

On another note, general and specific mandatory requirements as to GPP could be inserted at the EU and national level as a more demanding and arguably efficient exercise. A general mandatory obligation of procuring green could incentivise the public procurers to use the existing supporting GPP tools and implement GPP in practice, minimising the perceived legal risk of doing so by explicitly demanding sustainable behaviour. This could be achieved by defining the terms of Article 18(2) of Directive 2014/24/EU, e.g., what are the appropriate measures to ensure tenderers’ compliance with environmental law, expressly allowing for Member States to make GPP mandatory—defining what “shall” means and what are “appropriate measures”, as well as explicitly communicating to the Member States that they can mandate GPP themselves. Specific mandatory requirements could furthermore be inserted in the EU legal framework in several different ways, ranging from the creation of user-friendly procedures at the EU or national levels [139], establishing a hierarchy of award criteria nominated in Article 67 of Directive 2014/24/EU with a preference for life-cycle costing or conversely mandating its use or further developing eco-labelling and its use [107].

These considerations call for further scholarly attention to resolve the complexity and legal uncertainty that the current legal framework at the EU level brings, caught in between the aims of ensuring the best value for taxpayers’ money and the strategic role of public procurement in supporting the transition towards a (environmentally) sustainable society.

5. Conclusions

The present work analysed de jure and de facto limitations to a broader EU GPP uptake in light of the need for public purchasing to contribute effectively to the sustainability quest, while simultaneously legitimising further action in the field of corporate law. Reaching beyond the legal framework of Public Procurement Directives, accounting also for CJEU case-based limitations to environmentally conditioned public procurement practices, arguments have been presented for a simplification and modification of the existing EU public procurement legal framework, culminating in a proposal for a more mandatory approach to GPP. Highlighting the complex and interdependent nature of the applicable EU freedoms and the EU level public procurement legislation, especially in light of the application of the “link to subject matter” requirement, the present work calls for clarification of the existing legal framework and for its simplification.

Building on the experience with sectoral mandatory legislation on the matter, several possible trajectories were defined for the future development on the field. The work acknowledged the role of leadership, organisational engagement, and the necessary accompanying activities for enhancing the knowledge on GPP practices, as well as the importance of market engagement through the innovative public procurement procedures, yet it focused on solutions in the framework of procedures currently the most used in procurement practices. Advocating for the clarification of provisions of the Public Procurement Directives, the omission of the “link to subject matter” criterion, the insertion of certainty for Member States that they are allowed to mandate GPP in their respective national legal systems, while limiting the use of the lowest price criterion to the cases where environmental criteria have already been considered in at least one of the procurement stages, the article illuminated the possible actions in the established legal framework that could significantly aid the further development and higher uptake of GPP practices across the EU.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 789461 (SCOM Project—Sustainable Company).

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the work of Tomás Gabriel García-Micó on Section 5 of the original draft and his indispensable contributions in the field of blockchain considerations and smart contracts.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bergquist, A.K. Business and Sustainability: New Business History Perspectives. SSRN Electron. J. 2017, 18–34, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nielsen Company. What’s Sustainability Got to Do with It? Linking Sustainability Claims to Sales. 2017. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/reports/2018/whats-sustainability-got-to-do-with-it.html# (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Peretz, M. Want to Engage Millennials? Try Corporate Social Responsibility. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/marissaperetz/2017/09/27/want-to-engage-millennials-try-corporate-social-responsibility/#1b8943a96e4e (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Sjåfjell, B. Redefining Agency Theory to Internalize Environmental Product Externalities. A tentative proposal based in life-cycle thinking. In Preventing Environmental Damage from Products. An Analysis of the Policy and Regulatory Framework in Europe; Maitre-Ekern, E., Dalhammar, C., Bugge, H.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 101–124. ISBN 9781108500128. [Google Scholar]

- Sjåfjell, B. Beyond Climate Risk: Integrating Sustainability into the Duties of the Corporate Board. Deakin Law Rev. 2018, 23, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International EU Agreements. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/international_issues/agreements_en.htm (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Walley, N.; Whitehead, B. It’s Not Easy Being Green. Available online: https://hbr.org/1994/05/its-not-easy-being-green (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Clarke, R.A.; Stavins, R.N.; Ladd Greeno, J.; Bavaria, J.L.; Cairncross, D.; Etsy, D.C.; Smart, B.; Piet, J.; Wells, R.P.; Gray, R.; et al. The Challenge of Going Green. Available online: https://hbr.org/1994/07/the-challenge-of-going-green (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Eisenstein, C. Let’s be honest: Real Sustainability May Not Make Business Sense. 2014. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/sustainability-business-sense-profit-purpose (accessed on 12 November 2018).

- Waygood, S. How do the capital markets undermine sustainable development? What can be done to correct this? J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2011, 1, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts, E.W. The Complexity and Legitimacy of Corporate Law. Wash. Lee Law Rev. 1993, 50, 1565–1623. [Google Scholar]

- The Janus Programme. Politics and Persuasion: Corporate Influence on Sustainable Development Policy; SustAinability: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission. Europe 2020: A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth COM (2010) 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Cheng, W.; Appolloni, A.; D’Amato, A.; Zhu, Q. Green Public Procurement, Missing Concepts and Future Trends—A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 176, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Harford, L. UN Environment and Environmental Law in the Asia Pacific. Chin. J. Environ. Law 2017, 1, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Watt, J.; Semple, A. The Procura+ Manual. A Guide to Implementing Sustainable Procurement, 3rd ed.; ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability, European Secretariat: Freiburg, Germany, 2016; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. Public Procurement: Costs We Pay for Corruption. Identifying and Reducing Corruption in Public Procurement in the EU. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/anti-fraud/sites/antifraud/files/docs/body/pwc_olaf_study_en.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Pollex, J. Regulating Consumption for Sustainability? Why the European Union Chooses Information Instruments to Foster Sustainable Consumption. Eur. Policy 2017, 3, 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Thai, K.V. Public procurement re-examined. J. Public Procure 2001, 1, 9–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, J.-J.; Tirole, J. Auction design and favoritism. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1991, 9, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagstad, S. Promoting fair competition in public procurement. J. Public Econ. 1995, 58, 283–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brülhart, M.; Trionfetti, F. Public expenditure, international specialisation and agglomeration. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2004, 48, 851–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Grappio, P.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Frey, M. Examining green public procurement using content analysis: Existing difficulties for procurers and useful recommendations. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 18, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.; Fischer, A. The european legal regime on Green Public Procurement: Corresponding and conflicting aspects of environmental law and procurement law in the EU. In Buying into the Environment: Experiences, Opportunities and Potential for Eco-procurement; Erdmenger, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 51–69. ISBN 9781351281393. [Google Scholar]

- Diófási, O.; Valko, L. Step by Step Towards Mandatory Green Public Procurement. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2014, 22, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Public Procurement for a Better Environment COM/2008/0400 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52008DC0400 (accessed on 23 January 2020).

- Simcoe, T.; Toffel, M.W. Government green procurement spill-overs: Evidence from municipal building policies in California. J. Environ. Manag. Econ. 2014, 68, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S. Role of Green Procurement in Driving Sustainable Innovation in Supplier Networks: Some Exploratory Empirical Results. Jindal, J. Bus. Res. 2017, 6, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. The Role of Public Procurement in Low-carbon Innovation. OECD Background paper for the 33rd Round Table on Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sd-roundtable/papersandpublications/The%20Role%20of%20Public%20Procurement%20in%20Low-carbon%20Innovation.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2020).