1. Background: Including Tenants in the Renovation Process

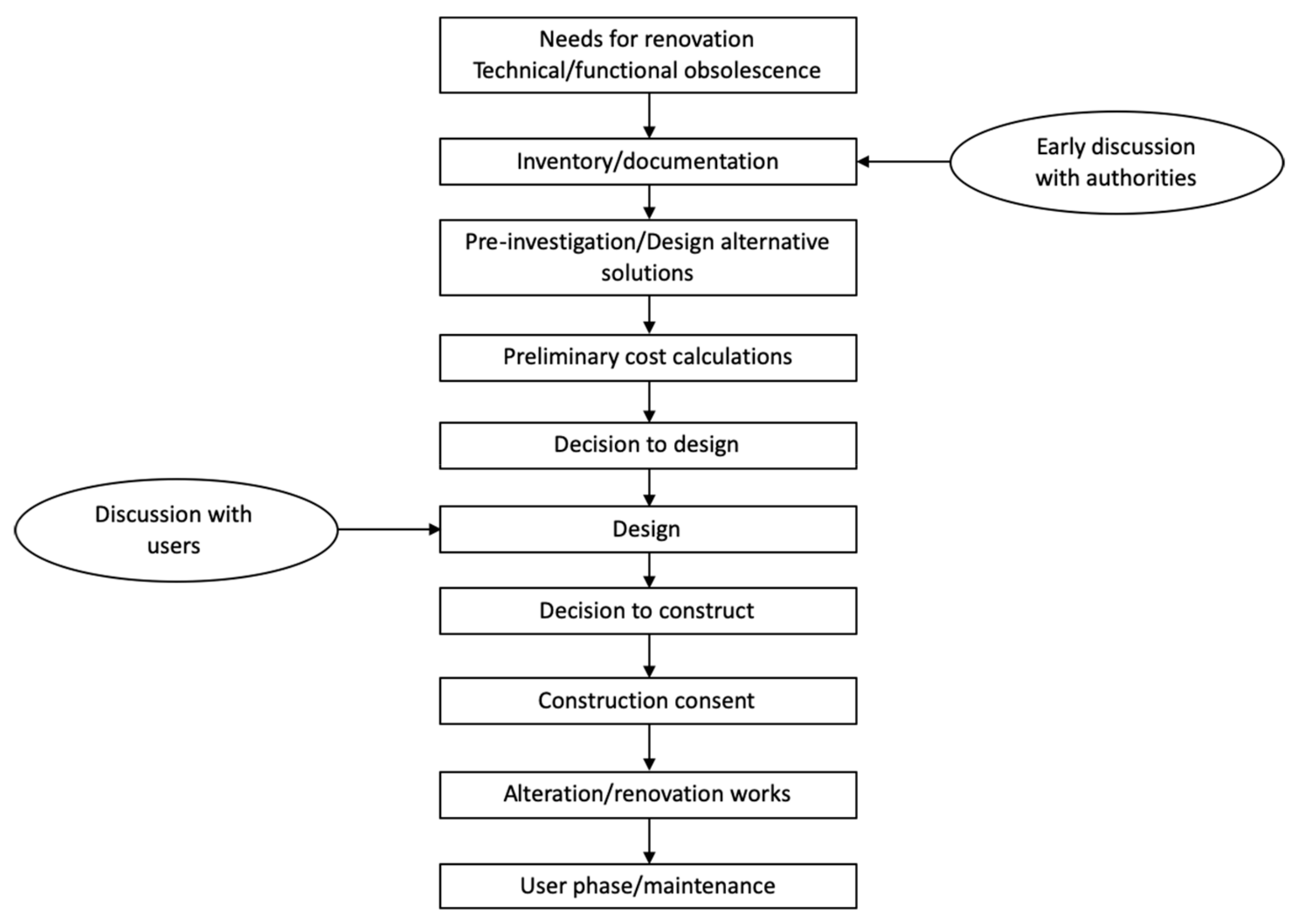

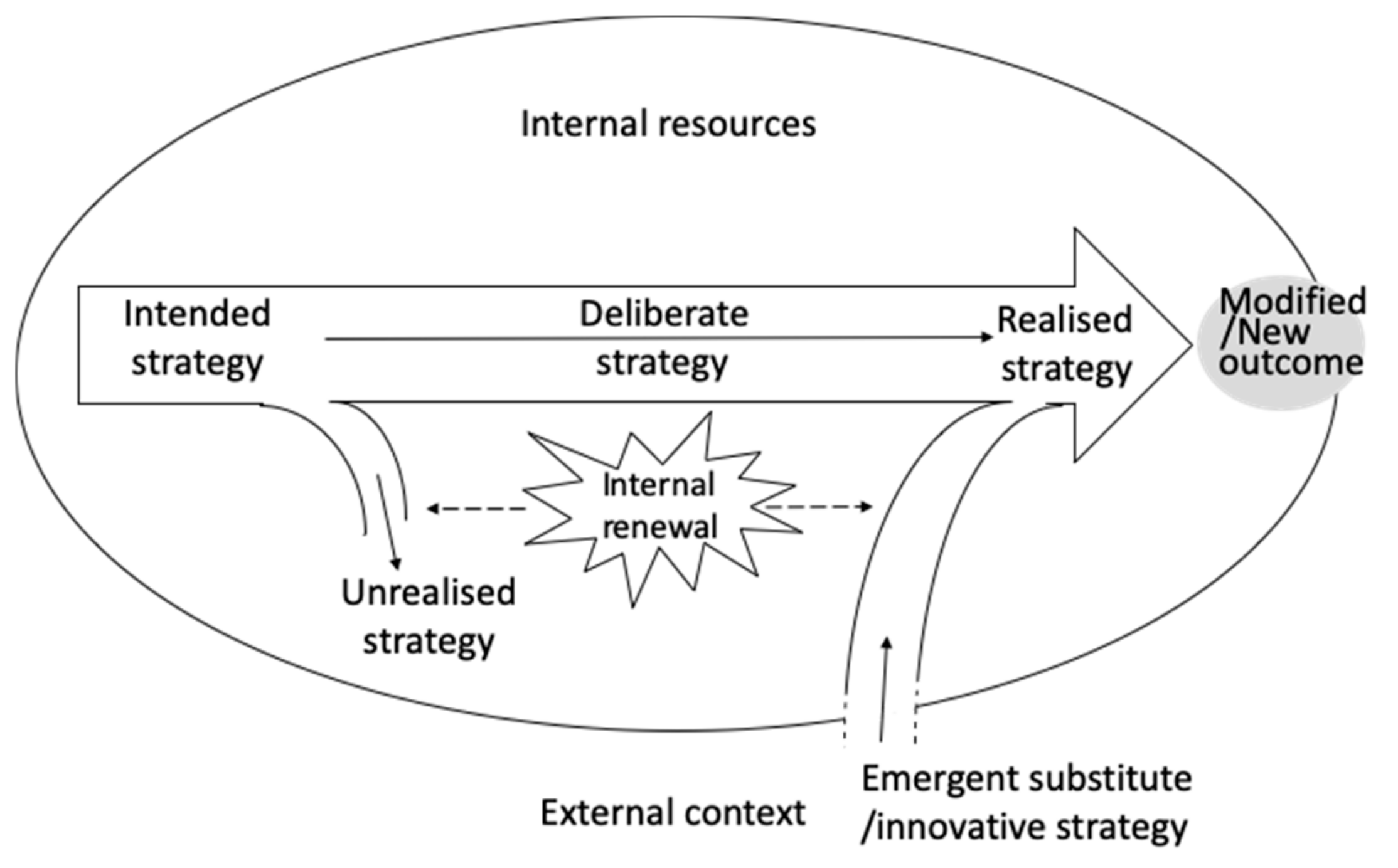

Housing renovation in the existing building stock has received increasing attention in recent years. In fact, a great deal of attention has been given to the technology and engineering issues that renovation entails. In contrast, dialogue and interaction between owners and tenants, and how such dialogue can influence the housing renovation process has been largely overlooked. We argue that the renovation process has come to be dominated by a Technology-and-Engineering-Focused model (TEF model) (see

Figure 1 below) which, we claim, is relevant for construction of new buildings rather than renovation of old buildings. Nevertheless, for some considerable amount of time, real estate companies have adopted the TEF model as their main strategy towards developing renovation processes. A serious consequence of this is that some real estate companies have experienced difficulty in achieving their project goals. The reason why they suffer from this problem is that the TEF model largely excludes users from the strategy process. In contrast to new construction projects, a renovation project has to take good care of the tenants who are already living in the building. In some cases, tenants even have to vacate the property so as to give way to renovation.

We argue that tenants are important stakeholders in renovation projects. Their interests are highly involved and they can also exert great influence on the project. For example, in Sweden, the tenants’ approval of large-scale renovations is prescribed by law. In cases where tenants remain inside the property during renovation, collaboration between tenants and the real estate company is crucial to the success of the project. Conflict between tenants and the real estate company is not uncommon during renovation, which often results in an increase of time and cost of the renovation.

Renovation has important implications for sustainability. On the one hand, in terms of resource use and environmental impact, renovation is often a better choice compared with demolition and new construction [

1,

2]. Studies have shown that the technical and economic life of a building exceeds the estimated service life of the building [

3,

4]. Renovation is an environmentally friendly way of extending the actual life of a building and can, e.g., improve the energy-usage of the building. On the other hand, in terms of social cohesion, health, and human well-being, a proper renovation can also improve the tenants’ standard of living by, for example, improving the building’s thermal comfort and air quality with better building envelops and ventilation systems, even for a reasonable budget. Nevertheless, renovation is often considered by real estate companies as a painful process because renovation is much more complex and uncertain than new construction in terms of decision-making, planning, and execution [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The technology-related and engineering problems that are caused by the complexity of the renovation process, including the qualities and deficiencies of the building, can easily occupy most of a real estate company’s energy and attention. In such a scenario, tenants run the risk of being ignored. For example, in the case study reported on in this paper, the degree of uncertainty regarding the building’s deficiencies was extensive. A further problem was that important documents about the design and existing installations were lacking. Researchers have put a great deal of effort into understanding the technical complexity of renovation and have suggested that, in renovation processes, emphasis in terms of time and resources should be devoted to the preliminary investigation phase if one is to achieve good results [

6]. In the schematic overview of a renovation process shown in

Figure 1 adapted from Thuvander et al. and Nordling and Reppen [

5,

9], great attention is placed on the technology and engineering issues in the renovation process, while the involvement of the tenants, the actual users of the property, is much more peripheral. We claim that this model represents a ‘rationalistic renovation process’ and mirrors beliefs concerning renovation that are shared within a large part of the construction industry. These shared beliefs, or ‘industry wisdom’ [

10], are based on a ‘cognitive and interactionist view of reality, which describes collectively shared ideas, beliefs, values, and norms about the rules of the game and possible strategic action in the industrial field’ [

11]. Obviously, in an ideal-type rationalistic renovation process, technology and engineering issues are placed in the centre and the tenants’ needs are highly ignored. This is what we call the ‘technology-and-engineering-focused model’ (TEF model).

The TEF model that is summarized in

Figure 1 assigns the property’s users just a very modest role in the renovation process. Note that ‘discussions with users’ appears only in relation to ‘design’, whereas all of the other elements of the process are carried out without any dialogue with users; including ‘needs for renovation/technical and functional obsolescence’, ‘inventory/documentation’, ‘pre-investigation/design’, ‘decision to design’, ‘decision to construct’, ‘construction consent’, and ‘alteration/renovation works’. The extensive exclusion of users and other stakeholders from the renovation process is liable to result in various kinds of conflicts and problems that exert negative influences on sustainability. So as to ensure a smooth housing renovation process that will contribute to sustainability, the involvement of people, both the tenants and other stakeholders, should be considered as a key factor in the renovation process.

2. Introduction: Method, Purpose and Research Questions

Using case study method, and applying Mintzberg’s definition of ‘strategy as pattern’ [

12], we present an analysis of a housing renovation project’s strategy formation and change over a seven-year period (2009–2016).

The purpose of the paper is twofold. The first purpose is to develop a new model with an inclusive approach that differs from the TEF model for sustainable renovation. We describe, in the context of a Swedish real estate company, how the TEF model was used and how they failed to achieve their goals. We also map out how the company developed a new model, which moved away from the TEF model to a more user-oriented approach. In a user-oriented approach the tenants and other stakeholders are included in the strategic decision-making processes associated with renovation. Based on our case study, we develop (and describe in some detail) a user-oriented model (UO model) for renovation practices.

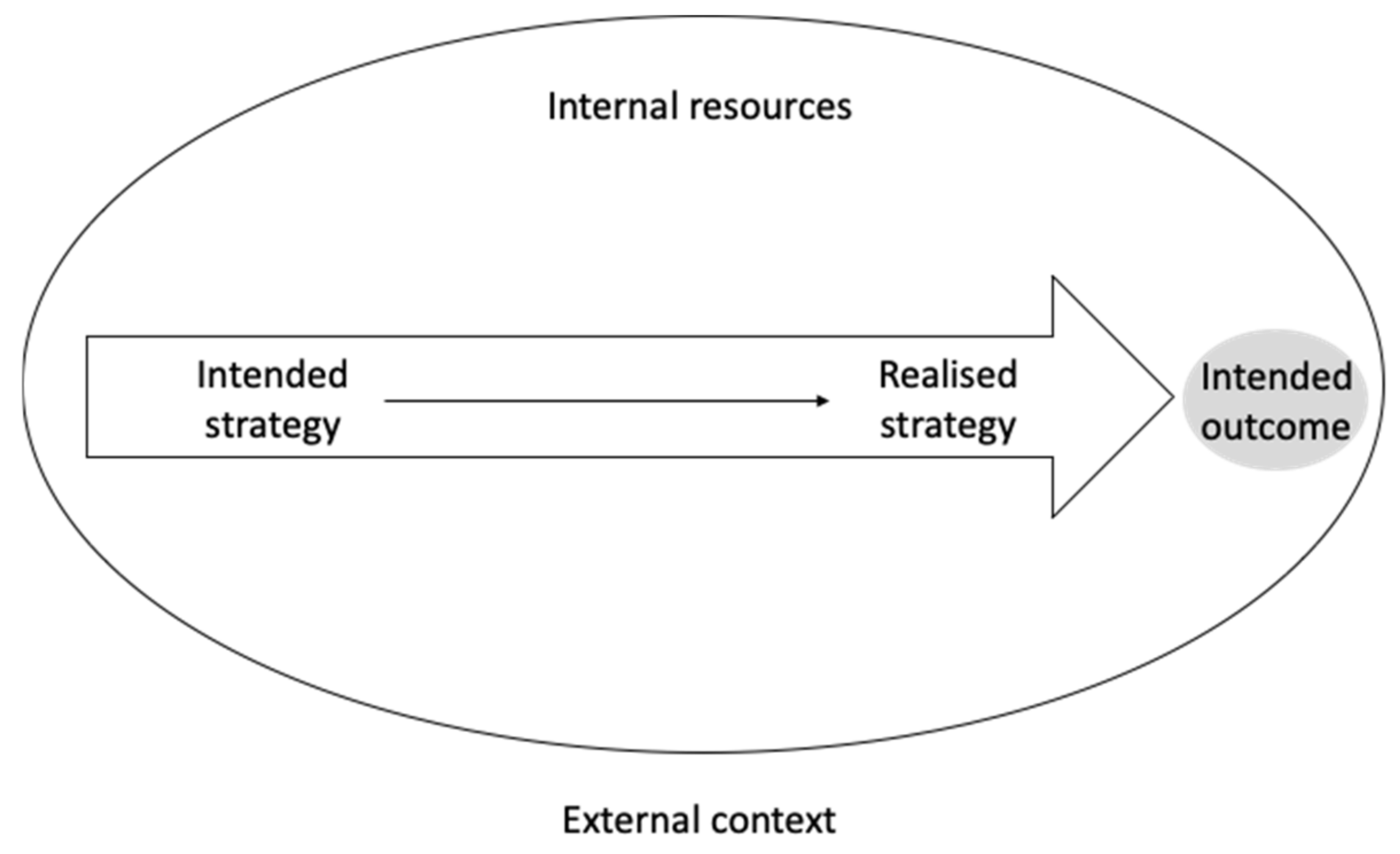

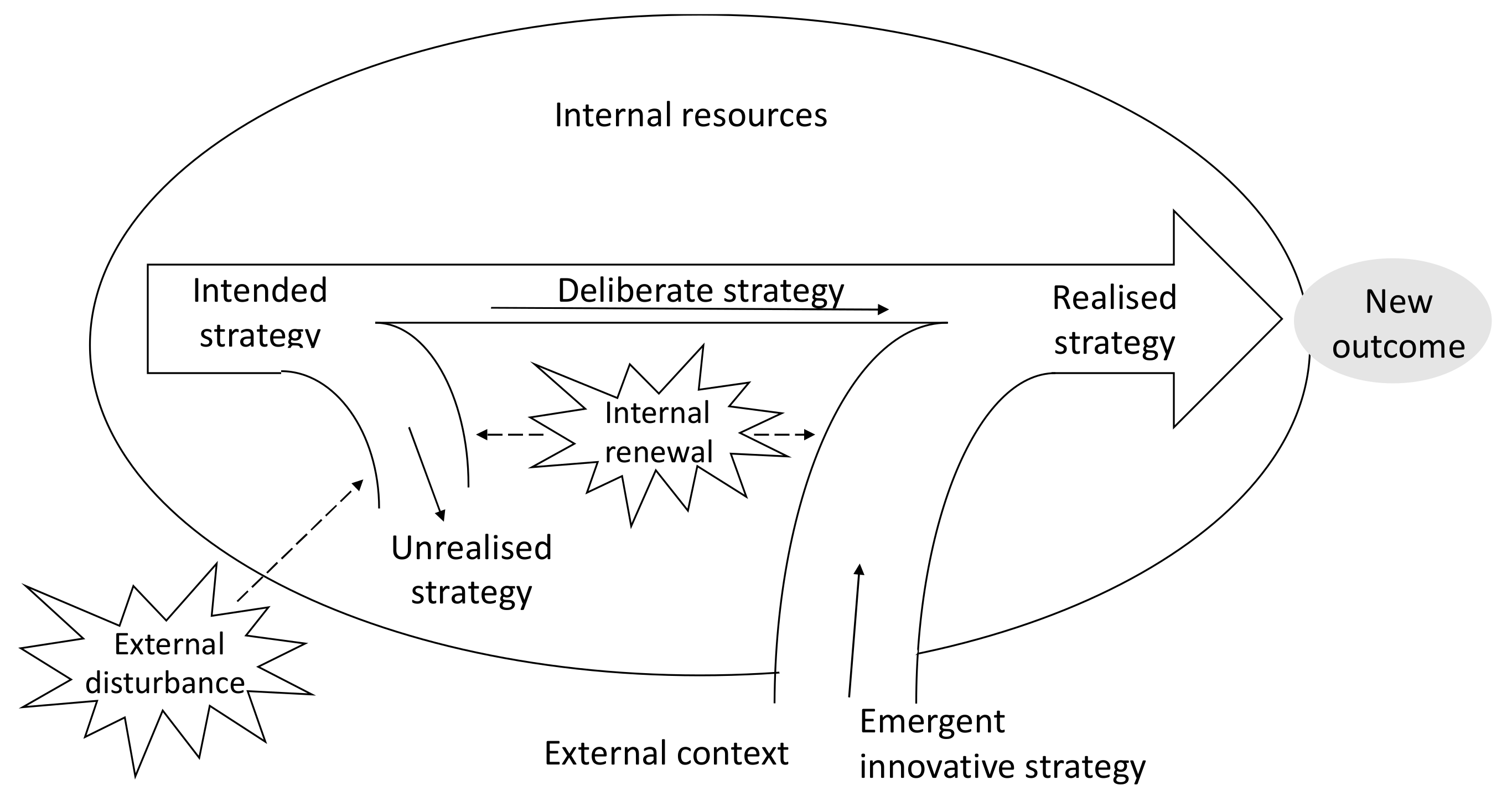

The second purpose is to add new knowledge to Mintzberg’s ‘strategy-as-pattern’ discourse. Mintzberg [

12] considers ‘strategy’ to be a dynamic process, with the ‘intended strategy’ as a point of departure. In the process of strategy actualisation, part of the ‘intended strategy’ is discarded (and is re-labelled as ‘unrealised strategy’) and new parts emerge (‘emergent strategy’). However, this research tradition has, thus far, not considered the conditions under which strategy change takes place and how a new strategy emerges; i.e., the mechanisms of strategy change. This paper addresses this theoretical gap and suggests an ‘internal-external mechanism of strategy change’ be added to Mintzberg’s theory.

The research questions which we address in the paper are: (i) What are the theoretical and practical implications concerning the transformation from the technology-and-engineering-focused model to a more user-oriented approach? (ii) What are the mechanisms of strategy change in terms of Mintzberg’s theory of ‘strategy’?

In the following section, a brief literature review links the present paper to the scientific discourse on renovation strategy and social sustainability. Using this literature review as context, we introduce an analytical framework, which can be used to understand strategy formation and change in renovation. The fourth section of this paper presents our research design, data collection, and data analysis methods. The fifth section provides a general background of the case study and the real estate company. The sixth section presents the main findings of our study. In the seventh section, we discuss the theoretical contributions and practical implications of our findings from the case study in relation to Mintzberg’s model of ‘strategy-as-pattern’. In the eighth section four ideal types of strategy change are presented and discussed with examples from our case. In the final section of the paper, we present our alternative model of user-oriented housing renovation and discuss the model’s implication to social sustainability.

3. Literature on Renovation, Strategy and Sustainability

We define renovation as ‘the consistent upgrading of a building’. There is no generally accepted definition to describe building changes [

5]; instead, there exist a large number of overlapping terms. Common terms are, for example, alteration and adaptation. Some authors use the term renovation to indicate ‘a minimum of intervention’ [

13], while others see the term as referring to a more ‘consistent upgrading’ [

14]. In general, a renovation process has very similar phases as are found in the process of new construction. According to Thuvander et al. [

5], the phases in new construction are ‘pre-design’, ‘preliminary investigation’, ‘design’, ‘construction’, ‘commissioning’, and ‘occupancy use’. While renovation contains quite similar phases as new construction, it is different from new construction. The only real—but crucial—difference is that the building’s users are in place from the start, and the renovation strategy of a real estate company should certainly take this into consideration. Perhaps related to the general absence of users in renovation strategies, there is also a lack of literature discussing user-orientation and its implication to sustainability in renovation. Previous research on ‘strategy’ in the literature on renovation and sustainability is scarce, as well as on ‘renovation’ in the relevant literature on strategy and sustainability. Lind et al. [

15] discuss the social aspects of sustainability in the context of renovation, but, to these scholars, the term ‘social sustainability’ refers either to ‘affordability’ or to ‘the ambition to create mixed communities’ defined as having ‘a low level of segregation between different income and ethnic groups’. In a recent article, Mjörnell et al. [

16] claim an increasing interest in sustainability and social responsibility from real estate companies. Since the role of existing users is the main difference between new construction and renovation, we argue that the process of interaction and dialogue with users is a necessary condition for achieving sustainability, particularly social sustainability, in housing renovation, which is what we call the ‘UO model’.

4. A Theoretical Framework for the Analysis of Strategy Formation and Change in Renovation Projects

In this paper, strategy is defined as ‘the guideline of actions that an organisation uses to achieve its goals’. We employ two important arguments from the strategy literature so as to describe how strategy is formulated and changed.

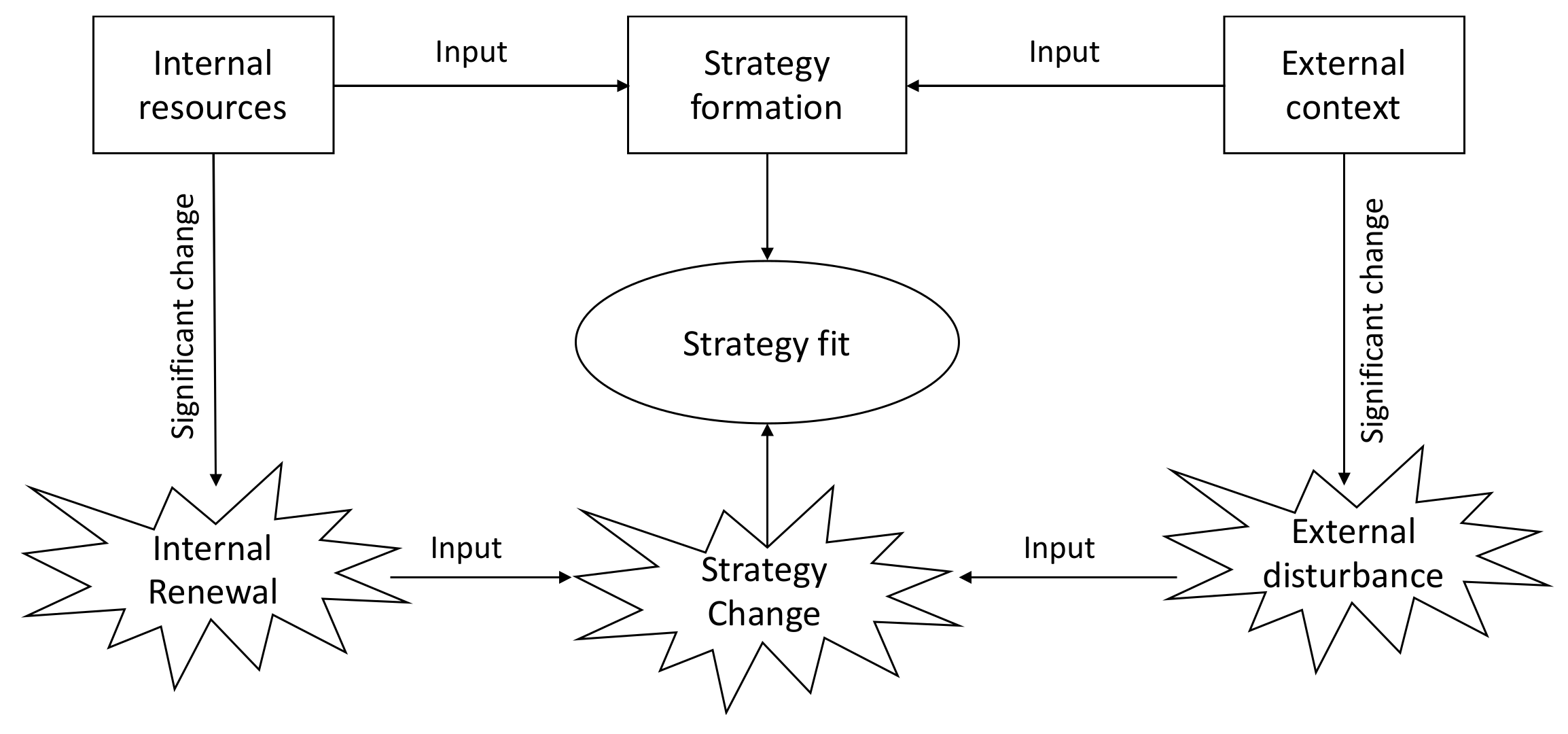

Firstly, we present strategy as a mediating force, which matches the internal resources and the external context [

17]. The term internal resources refer to tangible assets, such as financial and human resources, inventory, and machinery. Importantly, internal resources also include intangible resources; including the organisation’s vision, shared values and beliefs, organisational routines and practices, organisational reputation, information, knowledge, and social connections [

18]. Such intangible internal resources typically have a broader and more stable influence on organisational behaviour than tangible ones. External context includes industrial wisdom, business opportunities, competition, law and regulations, technology advances, and stakeholders (including customers and suppliers). Strategy formation is a process of matching the internal resources with the external context. The degree to which such match is made is the so-called strategic fit. A project’s performance depends on the extent to which the internal resources fit the external context through the formation and actualization of strategy. The function of strategy is to match the internal resources with the external context. Therefore, a change in internal resources and/or external context may consequently lead to strategy change.

Secondly, we argue that strategy is a dynamic process. Strategy is not a once-for-ever guideline but, rather, it is a changing process where old parts are discarded and new elements emerge. Mintzberg’s ‘strategy-as-pattern’ theory captures the dynamic nature of strategy and allows one to consider the process of strategy formation along a whole process of actions. The starting point in this theory is an ‘intended strategy’. In the process of implementing the intended strategy, part of it is discarded, part of it is actualised, and new emergent parts are included. The discarded part is the so-called unrealised strategy. The rest is actualised and becomes deliberate strategy, while the new part that is included is the emergent strategy. One can summarise Mintzberg’s strategy pattern as:

Given the above, we now ask: (i) What caused the unrealised strategy to become unrealised? (ii) What caused the emergent strategy to emerge? In summary, we interrogate the causal mechanisms that lie behind strategy change.

According to the theoretical claims mentioned above, strategy is the outcome of the process through which an organisation matches its internal resources and external context in strategy formation thus pursuing strategy fit. When internal resources are renewed and the external context is disturbed, the strategy that has been adopted thus far will have to change accordingly, i.e., strategy change happens. In this paper, internal renewal refers to a significant change in internal resources, such as hiring key employees, gaining or losing sizable financial resources, adopting game-changing new technology, etc. External disturbance refers to significant change in the external context, such as critical new laws and regulations, a technological revolution, a fundamental change in consumer behaviour, the emergence of strong new competitors, etc. Using these categorisations, we develop the theoretical framework as shown in

Figure 2. We apply it so as to present a detailed description of the process of strategy formation and change in our case study of housing renovation.

5. Method and Material

The research design included both semi-structured interviews and text analysis. Interviews were conducted from autumn 2016 to spring 2019 with four representatives from a housing company that were working on the renovation process, and with one stakeholder from outside the company who was also involved in the process. Furthermore, six households directly affected by the renovation process were interviewed. The interviews with the professionals took place at their current workplaces and the interviews with the tenants took place in their homes. The interviews were about one hour in duration and were recorded and transcribed. The text analysis that we conducted included project plans and documents from the housing company, but also material collected from the tenants. The events before and during the renovation were reported on in the local newspaper and we were provided with a number of newspaper clips that had been collected by the tenants. Other material such as videos about the history of the building, a website built by one of the tenants with documentations of the renovation, court decision documents, online news reports and discussions, were also used as complementary materials of our investigation.

6. Case Description

6.1. General Information about the Renovation Project

The property that was subject to renovation is considered to possess several positive architectural qualities and it was one of the first buildings in Sweden that was inspired by the ‘functionalistic’ architecture movement. The property was built in 1938 and was considered to be ‘modern’ at the time. It included a mix of sixty small and large apartments—the latter intended for relatively well-off people.

The building was bought by its present owner (a housing company) in 1999 from a private owner who was a relative of the constructor. The property had been kept in the family and no major renovations had been made. Consequently, the building was in rather poor condition at the time of its sale in 1999. According to the ‘rationalistic’ model of renovation (see

Figure 1), the motives behind renovation are technical needs and requirements. However, this was not the argument that was put forward when the housing company initiated its plan to renovate the building. Actually, many tenants had made renovations to their own apartments and consequently did not think that any major renovation was needed. According to Real Estate Manager ‘A’, the residents did not perceive themselves as regular tenants, but more like the owners of their apartments:

The former owner had told the tenants: You can do what you want in the apartment, but I am not going to pay for any renovations or something like that.

We thus note that the former owner’s management strategy for the building was a particularly laissez faire strategy.

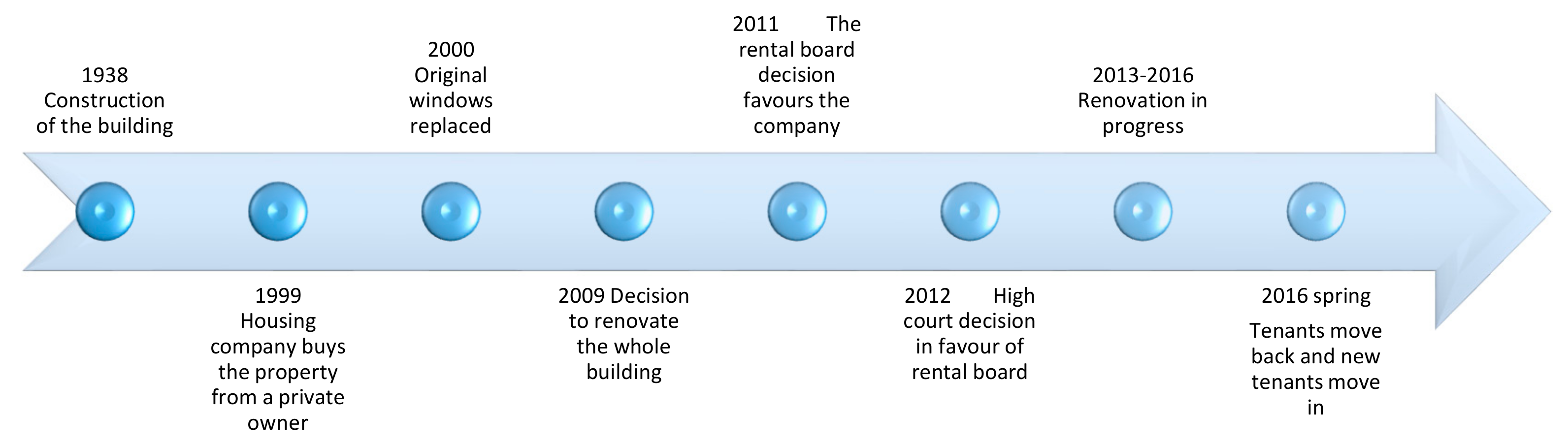

With the present owner, the building underwent two renovations. One was a small-scale renovation in 2000 and the other was a significant renovation that took place from 2009 until 2016. In

Figure 3 we present these renovation processes chronologically, starting with the purchase of the house in 1999 and ending with the completion of the large renovation process in 2016.

6.2. Renovation Project 1: The Replacement of the Original Windows

When the housing company bought the house in 1999, the majority of the tenants wanted to buy the house themselves and organise it as a ‘tenant-owner cooperative’. They did not succeed in buying it, although they had registered a tenant-owner cooperative in anticipation of their buying it. However, the building was placed as an asset in a company and then sold to the present owner, together with another building. Consequently, the tenants did not have the opportunity to buy the house.

The poor condition of the house led to a decision to remove and replace the original windows in 2000, despite their historical and cultural value. The original windows were designed and constructed by the original constructor in the 1930s. Many of the tenants were not in favour of the decision to replace the windows. This disagreement was not only because the tenants believed that the new windows did not have the same quality as the old ones, but also because the new windows had a smaller glass area than the original ones, so less daylight could enter the apartments. In this particular renovation, there was no formal need for the housing company to obtain approval from the tenants, because the renovation or replacement of windows is considered to be ‘regular maintenance work’ and, furthermore, there was no rent increase associated with this renovation. The relationship between the housing company and the tenants was somewhat strained when the house was sold in 1999. This relationship deteriorated even more so with the removal of the original windows, something which prompted strong reactions from the tenants. The tenants contacted the media, and, for the first time, the tenants’ dissatisfaction with the management of the building was expressed openly. Headlines in the local paper included: ‘Window expert critical to decision’ and ‘tenants criticize the change of windows’ (our translation). The tenants’ concerns consisted mainly of criticism for not preserving the original architecture of the building. Some of the tenants were journalists, and thus enjoyed access to the media. Despite of the criticism and complaints that were directed at the renovation, the company went ahead and removed and replaced the original windows with new modern windows.

6.3. Renovation Project 2: Significant Renovation of the Whole Building

6.3.1. The Decision to Renovate

The housing company had not carried out any really large-scale renovation projects before, so when they were starting to plan the broader Renovation Project 2, Real Estate Manager A, who formerly worked as a rent negotiator for a property owner association (Fastighetsägarna), wanted to make an inspection of all of the apartments. Information about this intended inspection was sent out by mail to all of the tenants.

At this point, there was already some growing suspicion towards the housing company, and a black market for rental contracts in the property had developed, because the rents were lower than in the surrounding area and the building was popular and well-known.

The resistance against us was great, and many of the tenants had invested a large amount of money in their apartments, it seemed as if they did not know that they lived in a rental apartment. (Real Estate Manager A.)

There was strong cohesion between the tenants in the house and we controlled there was no destruction, we helped each other, and this was a value that the housing company did not perceive of but broke down, we were worthless, we were only seen as guests paying a rent. (Tenant A.)

Immediately there was resistance on behalf of the tenants—they did not want to let the housing company into their apartments: ‘They were suspicious towards us and thought we had bad intentions’, said Real Estate Manager A.

When we finally got into most of the apartments, we discovered that the building was in worse condition than we thought. There were renovations inside the apartments that had not been properly made, they were not done by professional craftsmen, and there were for example jacuzzis that had not been installed in a proper way. The bathrooms and kitchens were not in good condition, there were mould problems everywhere (Real Estate Manager A).

Another problem with the building was that it lacked consistency and logic behind the installation of services; bathrooms and kitchens are normally situated above and below each other in an apartment building, in order to minimize the plumbing and electrical systems. The problem that the company was faced with was that the renovation had to be made simultaneously for the entire building, since the wiring was intertwined between different sections of the house. It was not possible to renovate only some bathrooms or kitchens, since there was no logic between the different floors and apartments in terms of wiring and pipes. Furthermore, there was also poor (or no) documentation of the original (and tenant’s) installations.

After all of the inspections were made, the plans for the renovation were clearer. Thereafter, the housing company invited all of the tenants to an information meeting where they presented the housing company’s renovation plan. This meeting took place in 2009. The tenants’ reactions to the proposed plan were not positive; in fact, there was an atmosphere of resistance. One representative of the housing company reported: ‘I have seldom been so close to getting rotten tomatoes thrown at me’ (Real Estate Manager A).

Most of the tenants attended the information meeting, and everyone wanted to know what the rent level would be after the renovation was completed. Real Estate Manger A was considered by the tenants to be linked to (and was thus stigmatized by) the rental system, because of this person’s former job at the property owner’s association. Additionally, the tenants were suspicious of the renovation itself and the possibility of future increase in the rent that they would have to pay (should they wish to remain tenants).

The tenants were not satisfied with the renovation strategy that was presented and the outcome of the meeting. They voiced their opinions of this matter quite strongly in the media. They argued that the planned renovation was a ‘luxury’ renovation. The leader of the tenants was a lawyer. Real Estate Manager A, who presented the strategy, also had a background as lawyer and felt that the housing company has thus far done the right thing. However, he also realized that the interaction between him and the other male lawyer (tenant) might be considered to be a somewhat unsavoury contest of egos between two male lawyers.

6.3.2. Dispute and High Court Decision

In a large-scale renovation where the level of accommodation standards is raised, Swedish law establishes that the tenants have to accept the renovation individually for each apartment. Most of the tenants did not approve of the renovation, and the housing company had to go to the Rent Tribunal (Hyresnämnden) to obtain approval for their renovation plan. The Rent Tribunal decided in favour of the housing company. The tenants then appealed to the High Court and the renovation plans were ‘put on ice’ between 2009 and 2012. The High Court decided in 2012 that the renovation was necessary and the company could go ahead with its renovation plans. The delay in the process meant that the project documents had to be updated, which increased the cost for the housing company.

Real Estate Manager A left the company in 2011 for a new position at another housing company. Real Estate Manager B, who had previous experience from a different housing company, was employed. By coincidence she watched a television program about important architecture in Sweden, where the house was highlighted as an historical building of architectural importance. Real Estate Manager B now realized that the company had to restore the building and take into account the cultural heritage perspective. The housing company decided to appoint a person who would be responsible for the cultural heritage aspects of the renovation process. There were no more big meetings with the tenants; from then on, the dialogue with tenants was conducted with the tenants’ representatives or individually, with each tenant. This was the strategy of Real Estate Manager B.

During the renovation process, several different people from the housing company were involved: (i) Real Estate Manager A; (ii) Real Estate Manager B; (iii) a construction project leader; (iv) a cultural heritage project leader; and (v) a ‘facilitator’ for the tenants (a project coordinator). The role of the ‘facilitator’ was to function as a link between the housing company, the construction company, and the tenants. Real Estate Manager A left the housing company when the renovation project was deferred by the High Court, after the tenants voiced their disapproval of the plan. Real Estate Manager B was employed before the renovation was restarted in 2013.

6.3.3. Restart and Completion of the Renovation

After the decision by the High Court, the tenants gave up their sometimes ‘vocal’ resistance against the renovation as such, and began to resist the requirement that they had to move out from their apartments during the renovation, since many of the tenants were old and some were sick. The housing company thus proceeded with the renovation plans, but also involved a ‘facilitator’ to find solutions for the tenants and their needs during the renovation. The company also decided that some of the tenants did not need to move out during the renovation. This caused a great deal of heated discussion about ‘justice’ and further delays in the renovation process.

The intended strategy used by the housing company as their motivation behind the proposed renovation was based on the age of the building, technical- and performance deficiencies, and the legal rights of the housing company regarding the proposed renovation. When the process started again in 2013, the strategy that was chosen by the company was to communicate individually with the tenants instead of organizing large-scale information meetings:

We did not have any large information meetings during my time in the renovation project, because I do not believe in having those types of meetings when there were as many as 60 households. (Real Estate Manager B.)

Furthermore, we note a change in strategy regarding how to communicate with the tenants, due to the tenants’ changing attitude towards the renovation process:

I think it’s a lot about communication and we got better and better in communicating with the tenants in this project. Because I think we underestimated the communication with the tenants at the beginning of the project and focused more on our rights as a property owner. (Real Estate Manager B.)

A property owner’s actions will be influenced to a high degree by their manager/owner’s directives and business plans, reflected Real Estate Manager B. The well-known building was also an important part of the branding of the company, and the company was of the opinion that it was important to keep the building in good condition, especially since the building was seen as a symbol for the company and their quality standards. The building is well-known in the city, so it would be noticed if it were not maintained properly. According to Real Estate Manager A: ‘It is a famous building in the city, and it is suitable for the owner’s branding to actually take good care of it.’

7. Main Findings: The Mechanisms of Strategy Change and Four Ideal-Type Patterns

7.1. The Mechanisms of Strategy Change

Based on the case analysis and using our analytical framework, the paper generates three main findings which are related to the role of ‘external disturbance’ and ‘internal renewal’, as well as the mechanisms of ‘strategy change’.

7.1.1. ‘External Disturbance’ as a Trigger for Strategy Change

The role of ‘external disturbance’ is twofold. First, it drives a situation to a position where change becomes available, as an option, and triggers the mechanisms of change. It is like an electric spark in an internal combustion engine. It provides the precondition for igniting the fuel for change, but does not necessarily lead to change. Second, an ‘external disturbance’ in itself may not necessarily lead to strategy change. This depends on the degree to which the external disturbance is perceived. If it is not felt or felt as light then the external disturbance may be absorbed or ignored without changing the project strategy. In our case, in Renovation Project 1 (window changing), the external disturbance (the tenants’ complaint) was ignored and the renovation strategy unchanged. However, in Renovation Project 2 (significant renovation), the external disturbance (the tenants’ strong complaint) could not be ignored; the company had to change their renovation project strategy.

7.1.2. ‘Internal Renewal’ as the Driving Force in the Formation of New Strategy

The role of ‘internal renewal’ is also twofold. First, internal renewal is not a prerequisite for strategy change. A firm can change its project strategy by its own volition with the same group of managers, financial resources, organisational routines, practices, norms, and beliefs. However, having said that, we note that new internal competence was the source of change from the old strategy, to the adoption of a new strategy. Nevertheless, if internal competence is not renewed, and an external disturbance is felt, it remains difficult to generate a new strategy, especially if the collective mindset within an organisation is stable and robust. In our case, Renovation Project 2, the new renovation strategy, which switched from the rationalistic model to a more inclusive model, can be attributed to the employment of a new real estate manager with previous experience of communicating with tenants, in the role of real estate manager at another company. The company claimed that the employment of this specific new manager was made without any intention of switching to a user-oriented approach. Nevertheless, at last, this new real estate manager played a critical role in introducing a new user-oriented mindset to the project.

7.1.3. The Mechanisms of Strategy Change Based on the Interplay of ‘External Disturbance’ and ‘Internal Renewal’

According to Mintzberg, ‘strategy’ is an intermediate force that matches internal resources with the external context [

12]. In our case Renovation Project 1, replacing the property’s windows constituted a minor external disturbance in the context of stable and unchanged internal resources. Consequently, strategy change did not occur. In Renovation Project 2, when the whole building was to be renovated, a large-scale external disturbance was felt (by the tenants, and, in turn, by the company vis a vis the tenants’ opposition and resultant court cases) and, in conjunction with an internal renewal (the employment of a new real estate manager), this resulted in a new strategy. A strategy that was informed by increased levels of user communication and acknowledgement of the building’s cultural-heritage aspects. The new strategy was the outcome of the external disturbance and the internal new competence.

7.2. Four Ideal Types of Strategy Change

The change from the old TEF strategy to the new UO strategy for sustainability demands the presence of two means; internal and external ones. We conclude this paper by describing four ideal-type circumstances for strategy change and their respective logic, using Mintzberg’s framework. Stylized illustrations of the four types are shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. We illustrate each type with examples from our case study. These four ideal-types show four different patterns with respect to how internal resources and the external context can jointly influence strategy change.

7.2.1. Ideal Type A: Neither External Disturbance nor Internal Renewal

When neither external disturbance nor internal renewal is present, a stable situation prevails. In this circumstance, the company formulates an intended strategy matching the internal resources and external context. The intended strategy will be actualised and the intended outcome of the project will be achieved.

7.2.2. Ideal Type B: External Disturbance But No Internal Renewal

In this circumstance, the external disturbance occurs and, as a consequence, the company has to change its strategy so as to deal with the disturbance. Part of the company’s intended strategy has to be discarded and an emergent strategy must be added. The emergent strategy is formulated by the same group of personnel with the same collective mindset as before, using the same financial and technological resources, the same information and knowledge base, and the same company vision, values, beliefs, and routines. Under such circumstances, one can hardly expect the emergent strategy to be a fully fledged, tried-and-tested strategy. The emergent strategy may only be a substitute stop gap, with only minor changes at the tactical level, and with no innovation included. As a consequence of this, the outcome(s) of the project may well be modified, but they will not be markedly different from the previous, intended strategy. On some occasions, when the external disturbance is not considered to be strong enough, the company may not even bother to change anything in their intended strategy, but may decide to keep the strategy the same as planned.

7.2.3. Ideal type C: No External Disturbance, But Internal Renewal

In this circumstance, the external context remains stable and unchanged while the organisation significantly renews it internal resources. This may include hiring a new manager (as in our case, Renovation Project 2), acquiring new machinery and technology, and/or changing its vision. Under such conditions, all of the change(s) in strategy will be solely directed by internal resources. Since there is no external disturbance, and hence no external demand for a change of strategy, such internally driven strategy change may lack legitimacy and an enduring driving force. Internal renewal may, although not necessarily so, lead to part of the intended strategy being discarded and the introduction of an emergent strategy. The extent to which the emergent strategy will either be a substitute strategy within the previous framework or an innovative new strategy depends on the level of innovativeness that is embedded in the internal renewal. In the case of housing renovation, one may expect that the replacement of the old real estate manager with a new person (with a new mindset and new competences) may be a more effective trigger for the introduction of a new innovative strategy compared, for example, the change of an old machine to a new machine with higher efficiency. Among all possible internal resources, it is claimed that a company’s human resources constitute the most active driver of change [

19,

20,

21].

If it is influenced by the innovativeness of an emergent strategy, the project outcome may result in just a modified version of the intended outcome. However, it may also give rise a new outcome that was not initially intended or desired.

7.2.4. Ideal Type D: Both External Disturbance and Internal Renewal

In this circumstance, external disturbance is felt and the organisation has to discard part of its intended strategy to deal with the external change. At the same time, new organisational resources are introduced. This is particularly the case when new people are employed and new social connections are built. Under such conditions, the doors to new ideas are more easily opened, resulting in the formulation of a new strategy. This ideal type represents the best-case scenario for an organisation to create strategy transformation. In such a case, the driving force of strategy change is twofold. On the one hand, the external context demands change. This pushing force provides urgency to, as well as legitimacy for, the change of strategy. On the other hand, the changes in internal resources also support change. This activating force offers the company capability to implement strategy change. The interaction between pushing and activating forces creates a situation where strategy transformation is likely to take place. With the realisation of the new strategy, the project is expected to yield a new outcome; one that is different from the intended outcome.

8. Discussion: Applying the Ideal Types to the Case Study

In our case study, the Ideal Type A model is relevant to the situation that existed before the property was sold to the present owner. At that time, the owner’s strategy was to do as little renovation as possible and let the tenants do what they wanted. Some of the tenants renovated their kitchen at their own cost, whilst other tenants left their apartments un-renovated. The landlord did not interfere with the tenants at all. Such a laissez-faire approach to renovation followed the path that the landlord intended. Note that there was neither external disturbance nor internal renewal during this period.

In our case study, Ideal Type B was present during the Renovation Project 1; when the original windows were removed and replaced. The tenants were vocal in their opposition to this first renovation. The media helped to amplify this opposition and went so far as to criticise the company for not preserving the historical value of the building. Notwithstanding this, this external disturbance was not strong enough to create any strategy change for the real estate company. At this point, note that the tenants’ arguments and requests were not supported by law, and the company did not legally need the approval of the tenants to conduct the renovation. In this situation, the external disturbance was too weak for strategy change. No intended strategy was abandoned and no emergent strategy emerged.

With regards to our case study, there were no circumstances that could be said to correspond to Ideal Type C (when external disturbance is absent but internal renewal is present). However, it is reasonable to imagine that, if the tenants were satisfied with the renovation process and the company changed its real estate manager, then there still would have been no strong motivation for the company to abandon its old strategy and create a new strategy.

Ideal Type D can be found in our case study, when the Renovation Project 2 was resumed and the company finally changed from using the TEF strategy and moved on to using a UO strategy. This strategy change can be attributed to the interplay between external disturbance and internal renewal. Firstly, the ‘external disturbance’ was instantiated by the tenants’ strong resistance to the proposed renovation. This led to court trials at two different judicial levels and negative reports in the media. The project was halted for a period of two years as a direct consequence of the lawsuits. This external disturbance triggered the company’s strategy change.

Secondly, the ‘internal renewal’ consisted of the hiring of a new manager. This individual manager proved to be the most active driver of change. When the project was resumed after a long pause, Real Estate Manager A (with a background as a lawyer) left the company and was replaced by Real Estate Manager B (who had housing administration experience). In contrast to the stereotypical lawyer who places great trust in logical thought, rights and rules, we might expect an experienced housing manager to be more used to understanding, persuading, and influencing people via personal communication. The employment of Real Estate Manager B provided the company the opportunity to re-assess the tenants as an important influential factor in their renovation strategy when the renovation project was resumed. Because of the real estate company’s claim that the change in staff was not intended as a means to change the strategy, one can argue that, if Real Estate Manager B had the same mindset and experience as her predecessor, such strategy change may not have taken place. Thus the case may have fallen into the Ideal Type B category, where only external disturbance exists. The company might have maintained the same strategy (or they might have just modified it within the previous TEF model) and expected the same intended outcome. With the employment of Real Estate Manager B, the company gained the necessary mindset, skills, and competence for the company’s strategy change.

We thus argue that the company’s change from the previous TEF strategy to a UO strategy was caused by the joint effect of the external disturbance (the tenants’ strong resistance to the proposed renovation) and the internal renewal (the hiring of a new manager). The company had never before adopted such a UO approach in the renovation projects that it had been responsible for. We see this as an emergent innovative strategy.

9. Conclusions: A User-Oriented Model

Mintzberg’s concept of ‘strategy as pattern’ takes strategy to be a dynamic process where changes happen on the way to realising an intended strategy. However, Mintzberg does not answer the question about the mechanisms of strategy change. We have thus asked: Under what conditions does strategy change take place? and How does a new strategy emerge? Based on our analytical framework for understanding the process of strategy formulation and change, and the analysis of the renovation projects in our case study, we argue that the mechanisms of strategy change are based on the interplay between external disturbance and internal renewal. External disturbance is the trigger of strategy change, but it does not, in itself, necessarily lead to strategy change, and particularly not for an innovative new strategy. The internal new competence was the source of changing from an old strategy to an innovative new strategy. Among all the resources that were available to the company, the human resource was the most active and effective for innovation. The employment of the new manager allowed for the emergence of new insights, new inspiration, and new norms for the creation of an innovative new strategy.

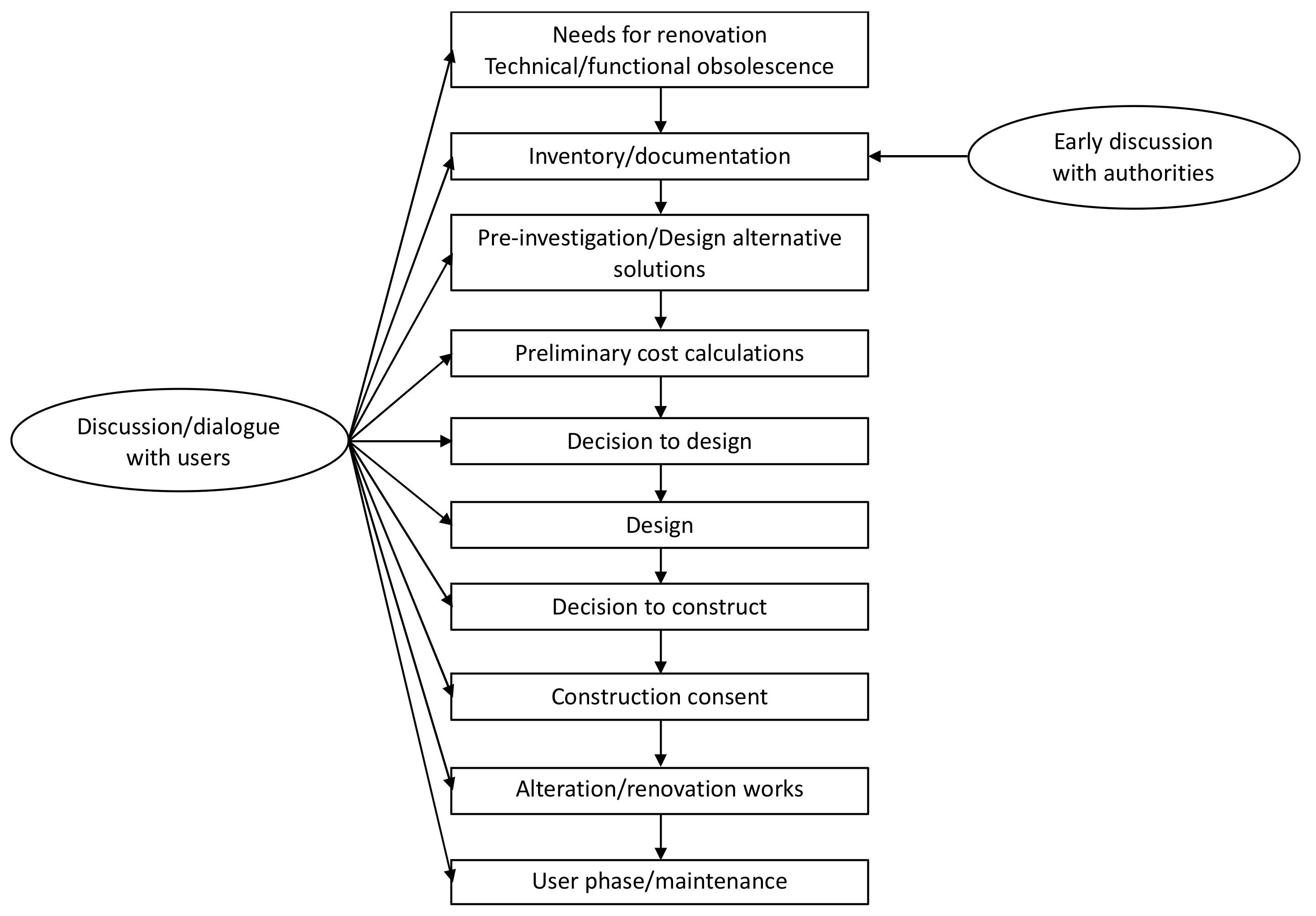

As replacement for the TEF model, we suggest a user-oriented model where user involvement is seen as integrated in the whole process of renovation; from the ‘assessment of needs for renovation’ to ‘the maintenance of the completed renovation’, as shown in

Figure 8:

In

Figure 8, and in contrast with the technology-and-engineering-focused TEF model presented in

Figure 1, we have added ‘discussion/dialogue with users’ at each and every step of the renovation process. It should be emphasised, however, that this is an ideal type model, and that in practice the dialogue within a UO approach may be more or less strong at different steps. For example, in our case study project, the UO model was introduced at a later stage of the process and not applied in the first steps. (In another study, we follow a case where the real estate company conducted user dialogues already two years before the renovation started, which improved the sustainability of their renovation process. See company report

https://www.helsingborgshem.se/nyheter/vi-har-vunnit-bopriset-2018.) The important thing is that the UO model represents a mindset oriented at user discussion and dialogue implying an overall expectation that users should participate in as many steps of the renovation process as possible. We argue that such a mindset would strengthen the prospects of socially sustainable renovation in particular.

The real estate industry needs to undergo a transformation from the rationalistic renovation TEF model (see

Figure 1) to the more inclusive UO model (see

Figure 8). According to our findings about the mechanisms of strategy change, the success of this proposed transformation depends on two important factors, internal and external. The internal factor is the successful introduction of a new mindset to the industry by recruiting, training, and empowering employees who possess the awareness and skills needed to work on the social aspects of renovation projects. The external factor is enhanced legislation and regulation that will promote renovation towards social sustainability.

This paper is based on a case study of a Swedish real estate company with existing theories of strategy formation and change. It develops a UO model with an inclusive approach for sustainable renovation to replace the problematic TEF model commonly used in the construction industry. It adds new knowledge to Mintzberg’s ‘strategy-as-pattern’ discourse by identifying some crucial mechanisms of change from a TEF strategy to a UO strategy. We claim that these mechanisms can to some extent be generalized to other similar contexts. On the ideal type level, the functions of external disturbance and internal renewal in affecting what type of strategy is chosen follow a consistent rationalistic logic, and should thus be fruitful in other similar cases as well. On the concrete empirical level the crucial variables introducing change may differ. In our case the external disturbance had to do with the court decisions and the cultural revaluation of the building in the eyes of the public, whereas the crucial internal renewal was due to the replacement of the old real estate manager with a new person with a different mindset and different competences. In other cases, other empirical variables may be more important in defining the contents of the ideal types of external disturbance and internal renewal. In future research, this should be further investigated in other qualitative or quantitative empirical studies of processes of housing renovation based on the Mintzbergian strategy perspective.