3.1. Extracting Social Order Embedded in House Plans

Ten houses from Yangdong town were diagramed as

Figure 4. They were built from the 15th century up to 18th century using the same vernacular style of the region, but still generated meaningful variations and thus no two houses look the same. The diagrams only highlighted three key building blocks, i.e., inner quarters, outer quarters, and gate houses (servants’ quarters), to show how visitors progress from the main entrance to the most central space of the house, the inner room (mistress’s room) within the inner quarters. The line-hatch indicates the inner room and the solid-hatch the outer quarters for the master. The orientation of each house was adjusted to locate the main gate (two parallel bars) at the bottom of each plan. The thick arrows illustrate how one takes the journey of going into the inner room from the main gate.

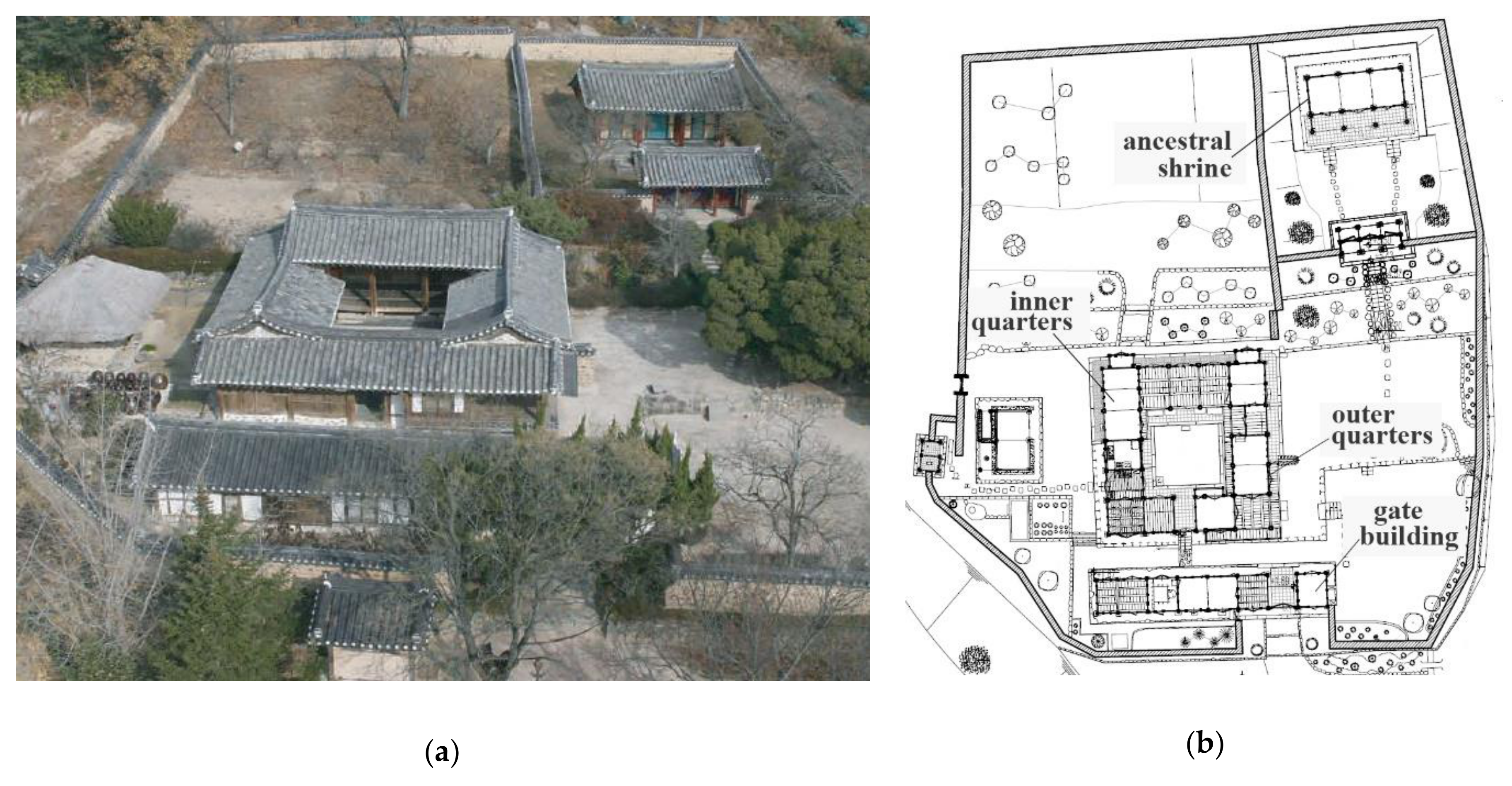

The first diagram is Seobaekdang, which was featured in

Figure 1. It is the earliest house found in Yandong, built in 1460. A visitor goes through the main gate first to start their journey. In this house, the gate forms part of the gate building that includes servants’ rooms. As discussed in the introduction, the gate building can be regarded as a type of servant quarters. Passing the gate, one encounters the outer quarters immediately, and thus make a left, then a right turn to proceed into the inner quarters’ courtyard. Finally, they need to step up to the

maru, a wood-floored hall to enter into the inner room. Put simply, the visitor passes the sequence of “gate house (servant quarters)-outer quarters-inner quarters”, the order of which physically embodies the social hierarchy between classes and sexes.

The second house, Muchumdang, has two outer quarters. In its first phase of construction, the outer quarters were accommodated within the inner quarters, but in the second phase, a separate building was added to make the master’s space more independent. This house, nevertheless, has a similar sequence of “gate-outer quarters 2—outer quarters 1—inner quarters”. In the third house, Guangajung, it is noticeable that the outer quarters become more prominent by sticking out of the inner quarters while they are still attached to it. In the fourth house, this becomes even more prominent. Many scholars agree that this reflects the increasing authority of Confucianism in the 16th century when the government announced regulations about separating different sexes and emphasized male dominance in the domestic space.

The fourth house, Naksundang, has a more complicated layout of building blocks. Between the gate building and the inner quarters, one has to pass the auxiliary building with the middle gate, and the outer quarters are not on the route. As the dotted arrow indicates, however, the visitor will have visual interaction with the outer quarters immediately after passing the main gate. Including this visual interaction as a part of experiential sequence, the journey will be “gate building–outer quarters–auxiliary building–inner quarters”. There are 5 houses that have dotted arrows, meaning the visitors experience visual exposure to the outer quarters without walking directly adjacent to them. There are even more complicated cases such as Houses 5, 8, and 10 where the visitors’ visual interaction with the outer quarters happens before they pass the gate building. Even in these cases, the deeper position of the outer quarters naturally generates the perception that the male space is hierarchically superior than the gate building.

House 6, Suzoldang, was built in the 17th century when the Confucian system was fully institutionalized in the Choseon dynasty. The 17th and 18th centuries were the time when there was a strong tendency of separating outer quarters to symbolize the status of the ruling male. Amongst those 5 houses built in this period (Houses 6 to 10), only House 8 is the exception where the outer quarters are conjoined with the inner quarters.

Overviewing all 10 houses built from the 15th to 18th centuries, it is recognized that there are variations within a certain level of formal unity. Also, there are gradual transformations through time reflecting socio-political changes. These typical houses in the Choseon dynasty consist of several building blocks, i.e., gate building (servants’ quarters), outer quarters, inner quarters, and other auxiliary buildings. While each house has a different arrangement, the order of these blocks maintain an acceptable layout to conform to the Confucian principle of social hierarchy. Thus, the servants’ space is located around the entrance area, typically accommodated in the gate building, or sometimes outside the territory, yet still near the main gate. Moving inside the house territory, the ruling-class living area appears. Almost as a rule, the outer quarters for males appear first while the inner quarters for females are hidden behind. As the outer quarters are always outward-looking, they allow a direct view over the main gate area, or sometimes outside the gate to easily interact with those approaching the house territory. This visually advantageous positioning of the male domain helps project its authority to the visitors, while spatially distancing itself from the servants’ space.

Table 1 shows summarized information of the 10 houses. They are categorized into three periods of socio-political changes in Confucianism—the early period, the established period, and the fully-institutionalized period. What clearly reflects this change is the degree of connectedness of the outer quarters. It was predominantly attached to the inner quarters in the early period, but as Confucian principles are established, it becomes increasingly articulated by being protruded from the inner quarters. Once the principles are fully institutionalized by national regulations, it becomes predominantly detached from the inner quarters to be an independent building.

The fifth column in

Table 1 shows the order of building blocks within the compound. In all 10 houses, the outer quarters (O) appear on route to the inner quarters (I), and thus the “O–I” sequence appears as a subset of all ten spatial sequences, proving the materialized social order by gender. As discussed earlier, there is a sequential pattern of “gate building-outer quarters-inner quarters” in the literati houses. There are, however, three houses that do not follow this order: Houses 5, 8, and 10 (bold text). Looking at

Figure 4, it is evident that although the outer quarters are in fact located deeper to the side than the gate buildings, they can visually interact with visitors even before the visitors arrive at the gate, owing to the carefully calculated allocation of the outer quarters, walls, and access routes of the visitors.

The final column in

Table 1 shows which building is located the furthest from the main gate within the compound. Shrines seem to be the predominant choice in 6 houses. It is known that from the 17th century, it was demanded by law that affluent households build an ancestral shrine within their compound. Hence, it can be said that the typical order of building blocks after the 17th century was firmly established for the sequence of “gate building-outer quarters-inner quarters–shrine”.

Figure 5 shows this sequence where building blocks for different users are aligned in a vertical axis following the hierarchical order. The gate building accommodates servants and functions as a protective front of the compound. Some servants were living outside the compound but their houses were still located at the front side of their master’s house for quick commuting and communication. The outer quarters were always designed to be outward-looking (the arrow attached to the circle indicates this) and this enabled active visual interaction with visitors and the outside world. By the 17th and 18th centuries, it became the most prestigious space in the compound due to its symbolic status and architectural presence (its thick-lined circle indicates this). The inner quarters, by contrast, were always inward-looking to prevent women’s activities from being seen from the outside. Although the outer quarters and inner quarters are always close to each other, the physical and visual interaction between them was strictly controlled by making doors and windows open in opposite directions from each other and sometimes placing a barrier such as walls between them. The dotted bar between male and female domains in the diagram denotes this. Lastly, on the farthest side of the compound is the ancestral shrine. The inclusion of this space for the dead became a norm by the 17th century. The thick line between the female and the ancestral domains denotes that the access to it was strictly controlled for ceremonial occasions.

The arrows on the right-hand side of

Figure 5 show symbolic polarities of spatial meaning in this sequence. The shallower position means a more accessible public realm while the deeper position a restricted private realm. All these meanings have been structured by Confucian principles for hundreds of years in the Choseon dynasty. When social values started to change radically from the end of the 19th century, this hierarchical ideal embedded in the house must have been challenged. By looking at vernacular houses built in the early 20th century, we can illuminate how this conflict was resolved.

3.2. Continuity and Change in House Design from the Early to Mid-20th Century

Figure 6 shows the site plan and serial views of Hong’s house built in 1934 in Pirun-dong, Seoul. It was an affluent residence built during the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945) when the old Confucian principles lost their governing power, at least at the official level. The dotted line on the site plan (a) follows a visitor’s journey from the gate building to the inner room (

an-bang) which became the most important room for the whole family by this time. By and large, Hong’s house preserves the typical characteristics of the Korean vernacular style that prevailed for hundreds of years, although it adopted some new periodic features such as long corridors on the periphery of the inner quarters and the outer quarters. It is composed of 5 building blocks along the long plots oriented in the north-south direction.

From the gate building facing the street (

Figure 6b), an interesting spatial sequence unfolds leading a visitor to the inner room. The whole layout was designed in a way to provide the visitor with a ritual journey in a controlled way. Once past the gate building, there appears the servants’ courtyard (

Figure 6c). Turning right, the middle gate appears as a second gateway (

Figure 6d). This allows the penetration through the outer quarters to arrive at the inner courtyard (

Figure 6e). The outer quarters, therefore, stand between the inner courtyard and the servants’ courtyard. By stepping up to

maru, the wooden-floored hall, one finally arrives at the front of the inner room (

Figure 6f). As seen from the 10 houses in Yangdong, this mistress’s room is always in the pivotal corner of the L-shaped inner quarters, between

maru and the kitchen.

Overlooking the whole journey, the process of transition from the outside to the most important room in the house seems quite dynamic and visually stimulating. The recurring alternation between the inside and the outside makes the cognitive distance of the route feel much longer than the reality. Because the route is loaded with many physical features such as turns, intersections, and building facades, it tends to be experienced as being longer [

17,

18,

19,

20]. This ritual journey effectively emphasizes the hierarchical order of “gate building-outer quarters-inner quarters”, exactly as it did for the 10 houses in Yangdong. There are, however, some changes that separate Hong’s house from them.

The biggest change was the absence of the ancestral shrine. Once it became no longer obligatory to build one inside the house, families began to use the inner

maru, the biggest hall in the house for the ancestral ceremonies. In the deepest part of the residence, where the ancestral shrine used to be, affluent families built other buildings, such as outhouses or auxiliary buildings depending on their needs. On the other hand, while the old sequence of “gate building-outer quarters-inner quarters” was preserved, the clear division between male and female domains became loose and flexible. It was even considered appropriate that males use the inner quarters and use the inner room as a master bedroom. One piece of architectural evidence for this is the orientation of the openings in the outer quarters. The windows and doors of these male quarters directly open towards the inner courtyard as in (

Figure 6g), which is unprecedented until the late 19th century. In contrast, openings do not allow visual permeability towards the servants’ courtyard with its double layers of non-transparent sliding doors (

Figure 6c). For the first time, the male building turns its back against the outside world and instead faces the internal female domain. This subtle, yet meaningful change, happened without any radical architectural transformation, but by a slight change in fenestration, and this evidently testifies to a significant change in the attitude towards the Confucian principle of separating men and women.

From the early to mid-20th century, as urban populations grew quickly, many speculative vernacular houses for the middle class were built in major cities. These houses were the compact version of vernacular houses and thus still inherited the old layout pattern of having inner quarters and outer quarters. The division of sexes, however, was not as strict as in the houses of the affluent ruling class since what was more important was to allocate a larger number of household members into a smaller number of rooms [

21]. As in

Figure 7, two basic building blocks were centered around the courtyard. Confined within an urban plot, abutting other neighbors, these houses naturally took the inward-looking layout pattern, but there were rare cases where the outer quarters maintained the old practice of looking outward, as in

Figure 7a. In any case, the inner quarters were always located on the farthest side from the entrance, while the outer quarters took the near side.

It was around this time that the outer quarters were used for various functions and occasions. Many houses used this block for tenants to generate income, while others used it for their family members or servants. Consequently, it was called by multiple names such as the gate building, servants’ quarters, and outer quarters.

3.3. Spatial Sequence Compared by Periods

Figure 8 compares four different spatial orders in three different periods. The first column represents the spatial order in the 15th to 16th centuries when Confucian principles did not make a huge impact on the house layout. As evidenced in

Table 1 and

Figure 4, the female quarters tended to enclose the male quarters. Thus, two quarters were basically nested in the same building block. Internally, however, the male zone was clearly demarcated by setting their openings towards the outside, while the female zone was inward-looking onto the inner courtyard. This is graphically represented in the figure by using dotted circles for the female and male territories, and the thick solid circle for the single boundary of the building block. It can be said that in this early phase, the compound was bisected into the upper-class zone and the servant zone.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, when Confucian philosophy was in full operation, the spatial division became more complex and hierarchical, as in the second column. Increasingly, the male quarters became detached from the female quarters and took the role of communicating the status and wealth of the household. Every aspect of daily routines was separated by gender (hence the thick dotted line between female and male domains) and, therefore, males did almost all their activities, including sleep, study, eating, and receiving guests inside the outer quarters. By this time, the ancestral shrine became a norm in every affluent house and was usually built in the farthest side of the compound with access to it strictly controlled for special ceremonial occasions (hence the thick line under it in

Figure 8).

From the late 19th century, when Confucian principles had been weakened by various social and political movements, the house configuration started to experiment with different ways of accommodating domestic culture, even though the spatial sequence of “servant-male-female” remained. The most important change is the shift in the emphasis from the male quarters to the female quarters. After the abolishment of discriminating laws in the late 19th century, the inner quarters regained its status as the central stage not just for the mistress but for the whole family. In this third phase of evolution, female and male zones re-defined their relationship by being integrated around the inner courtyard (hence the dotted circle around the two domains in

Figure 8). What appears to be subtle but significant in its meaning, is that the outer quarters began to face towards the inner quarters. When the windows are open, it can have an immediate visual connection with the inner quarters. Thus, the traditional way looking outward was reversed without any change in housing layout. In the figure, the upright arrow attached to the male domain indicates this.

The farthest side of the compound is now occupied by the outhouse for male retreat. It is the space for the master of the household to spend leisure time and receive guests. From the late 19th century, when there was no need to build a separate ancestral shrine, its ceremonial function was absorbed to the inner quarters, which has a large maru. Now the farthest side of the compound could be used for any additional uses, and Hong’s house chose to build a space for male retreat amongst others. The old territorial barriers between males, females, and ancestors were discarded and the whole compound could be easily accessed by all members of the household.

The last column in

Figure 8 shows the spatial order of middle-class houses built between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries in major cities in Korea. They are not the houses of the ruling class but provide a meaningful insight into the last phase of vernacular house evolution. Unlike the upper-class houses that declined after the early 20th century, their compact urban typology enabled them to thrive from the early 20th century until as late as the 1960s. As discussed in

Figure 7, the middle-class house normally has only two building blocks, i.e., the inner quarters and the outer quarters. While the former still retains its traditional function, the latter now has flexibility in its usage, accommodating tenants, servants or family members. Still, there were cases where it was used exclusively for males in the family, as shown in

Figure 7b. When the outer quarters were used for tenants and servants, the inner quarters had to accommodate both males and females of the family. Consequently, the spatial division by gender became increasingly blurred [

22].

Figure 8 shows this change by adding “male” to the female domain. The elongated circle below it is to show that the division between the outer quarters and the gate building has been blurred and integrated so as to accommodate various users and functions.

Overviewing the whole process of housing transformation, it is clear that the concept of separating building blocks into two, the inner and outer quarters, has persisted for hundreds of years from the 15th century until the mid-20th century. To adapt themselves to the social changes, Korean vernacular houses re-invented the way they were used. By re-thinking the way each building block was used, residents could maintain stability without radical change in housing morphology. Confucianism molded the spatial configuration of the house in the Choseon dynasty but the same setting could accommodate new lifestyles without conflict through creative re-distribution of activities.