1. Introduction

The reduction of budget deficits and (high) debt/GDP ratios is the priority for many countries in Europe. Nevertheless, public sector organisations need financial resources to invest and Local Governments (LGs) are no exception. “Borrowing is recognised as a simple way of procuring the necessary funds for an investment project in the short term, but which imposes the burden (of its repayment) on future taxpayers” [

1] (p. 305). Thus, Central Governments have reasons for concern if their taxes’ revenues were lower than expected [

2]. Moreover, with the onset of the crisis of sovereign debt, since financial markets are vulnerable to economic changes and public sector debt is no more risk-free, the cost of borrowing became unstable over time [

3].

The lack of fiscal discipline at different public administration levels emerged due to the deterioration of public finances, showing financial instability [

4]. The development of budgetary, financial distress can lead to the cost of debt rising with systemic consequences. So, the Central Governments had strong incentives to control the local budgetary process to avoid the misuse of LGs’ borrowing powers [

5]. Considering the differences in contexts and control approaches, the literature has identified several different municipal borrowing governance models. The Stability and Growth Pact currently in place within the European context seems to embody what the literature calls the Centralised Discipline and Control Model [

3,

6,

7,

8]. This model postulates the need for bureaucratic controls and relies on detailed rules that LGs must meet to borrow.

The banking channel has been the traditional funding source for LGs besides tax sharing and governmental transfers. The emergence of specialty municipal banks (such as Dexia Credit Local of France, Public Works Loan Board in the United Kingdom, BNG of the Netherlands, Banco de Credito of Spain, Credit Communal of Belgium, and Cassa Depositi e Prestiti on the Italian credit market) was functional to grant funds to LGs. The relationship with banks is deeply rooted in western Europe to create durable partnership relations with LGs [

9]. Even if municipal bonds have been issued worldwide over the decades to finance investments, their development in the European Union has been relatively slow [

3], despite that under specific conditions, municipal bonds are analogous to a standard bank mortgage [

10,

11].

LGs do not issue bonds like before because public finances become unsustainable when government borrowings are more expensive than the interest rate paid for borrowing from banks [

2]. The start of the European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact hindered municipal bonds’ spread as an alternative to bank lending, especially in unitary countries [

9]. The result is that the European municipal bond market is generally smaller than the sovereign [

12]. However, as Foremny [

13] has made clear, this affects unitary countries more than federations where sub-national governments’ prerogatives allow them to supersede those rules.

This paper investigates the Centralised Discipline and Control Model to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. (H1). The adoption of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model generates higher and hidden costs for the LGs which borrow from the financial markets;

Hypothesis 2. (H2). Under the Centralised Discipline and Control Model, municipal bonds are not a technically and economically feasible alternative to banks’ borrowing.

For these aims, the paper compares the use of municipal bonds against the borrowing from banks to figure out whether bonds are “a risky venture that the Center needs to control to protect all stakeholders” [

1] (p. 305), as the Centralised Discipline and Control Model would suggest. The empirical evidence is built on the municipal bonds issued in Italy in the last decades. Italy represents an appropriate context to carry out this study because it reflects a unitary state’s condition subjected to a Centralised Discipline and Control Model in which market-based funding methods have been introduced while the banking channel was dominant.

Additionally, the Italian municipal bond market has been recently investigated by Padovani et al. [

14] through a quantitative analysis aimed at identifing the factors that determine the cost of municipal bond determinants in the non-mature financial market. Despite the many insights the analysis offers, Padovani et al. neglected the state supervision costs. Therefore, this paper adopts a quant-qualitative mixed method to close this gap and shed light on these hidden costs. The results show the Centralised Discipline and Control Model’s role in making municipal bond markets non-mature. The paper is organised as follows: the next session reviews the control models developed by the literature.

Section 3 briefly describes the Italian local borrowing system, while

Section 4 presents the methods and the materials used for the analysis.

Section 5 shows the results to be discussed in the last section.

2. Models for the Control of Municipal Borrowing

With the beginning of the devolution and decentralization processes, LGs in many countries experienced different market-based options to expand and diversify the possibilities for funding their activities. For decades LGs have been looking for more “innovative” approaches to finance [

15], and municipal bonds have been internationally issued to finance investments. However, either because of the advent of risk-averse tendencies or global economy changes, the investment cost became very sensitive for more than ten years [

3]. To minimise such risks, Central Governments impose rules and sanctions on decentralised governments when they borrow. The rationale for these measures was to mitigate the risks arising from municipal bonds. The introduction of control measures is linked to the idea that LGs should adopt general principles of local borrowing control.

Though LGs have widely used this funding method in the past, seminal research encouraged the debate about reducing the risks associated with the municipal bond market. “There are certain general principles and methods of financial administration which all cities should adopt and which (…) should be embodied in a general administrative code” [

16] (p. 105). Addressing these risks, the literature that Ter-Minassian and Craig [

7] pioneered provided divergent models for municipal borrowing governance, which embody different mechanisms intended to enforce debt control, taking into account the context differences. The literature has identified four models for the management of municipal borrowing and different control approaches. These are “the market discipline and control model”, “the local political discipline and control model”, “the centralised discipline and control model”, and “the professional discipline and control model” [

3,

6,

7,

8].

Table 1 summarises the main features of the four models.

The Market Discipline and Control Model is strongly based on technical evaluations (e.g., ratings) and strictly depends on financial markets’ maturity; therefore, it cannot impose debt discipline on LGs in countries with high sovereign risk. Higher risk is generally associated with higher interest rates, and above a certain threshold, markets are unwilling to lend to over-indebted LGs. By contrast, the Political Discipline and Control Model exclusively relies on soft factors such as democratic accountability mechanisms. Since the risk of unsustainably high debt falls on local voter-taxpayers, it is up to them to establish whether the taxes required for repayment rise to unacceptable levels. This being the case, they might not want to re-elect local politicians, which ultimately represents the control over debt. Therefore, this model is largely unreliable in the short period because politicians may buy votes by reducing taxes, pre-empting the control of taxpayers. While facing technical factors is easier than tackling soft factors [

17], a model based on technical factors needs public sector accounting methods consistent with private practices [

7].

The Centralised Discipline and Control Model builds on bureaucratic controls and detailed rules that LGs are expected to abide. The Stability and Growth Pact is a prime example because it embodies bureaucratic control much like those laid down in this model. In fact, “European member states have been required to adhere to new governance parameters, comply with Fiscal Compact rules, accept debt consolidation processes, pursue balanced budgets while still being expected to respect Maastricht treaty requirements” [

18] (p. 882). Belonging to the European Union requires member states to accept debt consolidation processes in compliance with Stability and Growth Pact rules. However, several criticisms emerged. For example, “this model is difficult to reconcile with the administrative and political decentralization processes adopted in many countries” [

8] (p. 316). Moreover, precisely because international agreements have decided the criteria for monitoring local indebtedness, it does not reflect the specific features of LGs. Domestic Stability Pacts are the practical implementation of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model among European member countries: in fact, “the Stability and Growth Pact only holds Central Governments responsible for the compliance, urging a strengthening of control over local government accounts” [

19] (p. 114). In other words, this model flattens the decision process to the central level, failing to consider the local and regional differences. These shortcomings are evident within the Italian context, mainly due to the European integration process, which overshadowed powers’ devolution to subnational governments [

20,

21,

22]. The control model for local borrowing should be developed by balancing decentralisation and central needs for direction and control. “The increasing worldwide trend toward devolution of spending and revenue-raising responsibilities to subnational governments seems likely to come into growing conflict with systems of administrative controls by the Central Government on subnational borrowing” [

7] (p. 170).

Conversely, the Professional Discipline and Control Model is based on fiscal supervision rules as an alternative approach to the restrictive rules of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model. “Such rules are the public sector equivalent of bond ratings in private sector capital markets” [

3] (p. 16). Therefore, embodying technical factors developed for the public sector, this model meets the market’s needs while ensuring the sustainability of borrowing. Besides, since LGs chief financial officers may establish these rules, the concerns of LGs shall be considered. The United Kingdom’s Prudential Borrowing Framework (PBF) is an example of this model of borrowing control. “Although the PBF increases local autonomy, it is tempered by professional financial advice from Chief Financial Officers intended to ensure that all external borrowing is within prudent and sustainable limits, that capital expenditure plans are affordable and that treasury management decisions correspond with professional good practice” [

2] (p. 11).

3. The Italian Local Borrowing System

Central controls over capital expenditures and borrowings of LGs have traditionally marked the Italian public sector finance. LGs were allowed to borrow from Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, a specialty bank, and no particular expertise was necessary [

23]. LGs achieved financial autonomy during the European integration process, resulting in a reduced state influence over LGs. In 1995 the monopoly of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti ceased, and other banks entered the market, starting relationships with LGs by offering broader services, such as consulting [

24]. However, banks were not free to determine the lending rate, whose setting remained a prerogative of the Ministry of the Treasury that periodically set the maximum rate threshold.

In the same period, LGs could issue their municipal bonds, benefitting from financial and economic advantages, such as the quick collection of the amount and favourable interest rates, and exploiting fiscal benefits that bank loans could not offer [

25]. For example, the so-called tax retrocession entitled LGs to receive back part of the revenues from bondholders’ taxes when they were firms or corporations (including banks), cutting the overall cost of bonds [

10,

11]. The majority of bonds’ repayment schemes provide for coupons that include capital and interest shares under the French depreciation method, which banks use to draw up loans’ amortization plans. This makes municipal bonds analogous to a standard mortgage.

According to secondary financial data of CEAM System (courtesy of the Public Debt Directorate at the Ministry of Economy and Finance—MEF), between 1996 and 2011, 1544 bonds amounting to €12 billion were issued by municipalities. CEAM stands for “Market Access LGs’ Comunication”, and it is an IT procedure to collect and transmit quarterly data on borrowing to the Treasury Department. The outstanding debt in 2020 is €5.4 billion (MEF monitoring report 2020) and still represents a burden for public accounts. One-third of the emissions were at a fixed rate and constitute about two-thirds of all issues. The fixed rate is perceived to be less risky since it makes it possible to know in advance the exact amount to be repaid for every instalment. However, even if LGs could decide how to finance their investments [

21] and alternative financial tools became available to fund their investments, the Italian LG bond market has always been very small [

19]. According to a study by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) [

26], only the LGs able to face significant investment would benefit from reducing funding cost through the bond market, so that banks remained the most important lender to LGs. The main reason for the predominance of bank loans over bonds is the bond size, which should ensure an adequate liquidity level for it to be tradable on the market. However, even the largest municipal bonds are infrequently traded after issuance [

27], and in Italy a large number of bonds have been underwritten by banks and held to maturity [

25]. Just 12 out of 1544 were bullet bonds, i.e., debt instruments whose entire principal is repaid to the bondholder on the maturity date and traded.

Derivatives were the critical element of this funding scheme because they have been signed to hedge municipal bonds. As required by the Local Government financial law, all bonds issued by LGs have to be covered through sinking funds and amortizing swaps to guarantee that sufficient money would be available to redeem the bond upon maturity. However, “their risk characteristics and cost structures can be quite different from those of standard debt instruments” [

28] (p. 18). Additionally, despite the important hedging role, their use has not always been appropriate [

29]. Derivatives’ riskiness has been emphasized by the Italian Court of Auditors, which focused mainly on the collateral structure and the composition of sinking funds. In particular, Italian LGs used derivatives to circumvent the budget constraints imposed by the European Stability and Growth Pact in the short period [

30], despite burdening their budget with significant annual costs in the long term. In fact, rather than as hedging tools, derivatives have often been employed to finance current expenses using the upfront amount as a way to obtain liquidity in the year in which the derivative is signed, leading to accounting imbalances in the next years when the flows become unfavourable for LGs [

31].

So, the Central Government disincentivized municipal bonds by “manipulating” critical variables [

32]. First, it amended the fiscal framework for issuer and bondholder assuming any rights upon the taxes paid by bondholders, withdrawing the tax retrocession benefit to issuers [

10,

11]. Second, it imposed a ban that prohibited LGs from underwriting new derivatives contracts required for hedging municipal bonds [

31]. As a Member of the European Union, Italy has to comply with the Stability and Growth Pact to ensure the sustainability of its public sector debt. Due to the worrisomely high level of Italian public sector debt to GDP (about 135% before the COVID-19 pandemic started, estimated at 158% in 2020), the emphasis shifted to fiscal consolidation and the overall system moved back to centralism. Italian LGs do not issue bonds since the public sector debt reduction has become the overarching objective.

However, the aftermath of these restrictions is that LGs cannot renegotiate their bonds because derivatives and the underlying debt have to be considered simultaneously. They may modify the financial position only where the Central Government derogates that prohibition, allowing LGs to manage derivatives and buy back their bonds [

33]. They can also improve the cost of the outstanding debt if the Central Government grants new affordable resources, directly, as in the case of the recent “mutui MEF” operation, or through its specialty municipal bank Cassa Depositi e Prestiti. Otherwise LGs will pay a higher cost for their municipal bonds year after year until maturity (note that there are LGs exposed until 2048).

4. Materials and Methods

This paper utilizes an explanatory design [

34] that is a two-phase mixed method built on quantitative and qualitative data. The choice of mixed methods lies in the assumption that neither quantitative nor qualitative methods could satisfactorily reveal on their own whether the Centralised Discipline and Control Model would make the LGs’ cost of debt higher. Since “when used in combination, quantitative and qualitative methods complement each other and allow for a more robust analysis, taking advantage of the strengths of each” [

35] (p. 3), through a joint reading of the findings of each phase, the paper tries to address these questions as a whole. The quantitative phase’s goal is to assess the cost of borrowings when LGs issue municipal bonds by using bank loans as a benchmark. Building upon the initial quantitative results, the goal of the qualitative phase is to investigate the Central Government’s rationale for restricting LGs approach to funding to the only banking channel as a result of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model.

The relevant data to carry out the quantitative analysis were financial data of issued municipal bonds (e.g., date of issuance, maturity date, amount, interest rate, fixed or floating rate, currency, etc.) gathered from the MEF. Concerning the interest rate, since it does not reflect the real cost [

36], it was increased by 0.4282% to consider emissions and management charges. These elements were used to draw up each municipal bond’s amortizing plan to determine the overall interest costs. Two versions of the estimate were performed: one considering the effect of fiscal benefit as long as it was granted to LGs and the other considering the effect of fiscal benefit as if it were not withdrawn.

This paper considered 519 fixed-rate municipal bonds issued by cities for the estimate, while floating rate bonds were left aside. There were two reasons for the screening of fixed-rate bonds. On the one hand, the MEF dataset did not provide details about the spread-at-issuance (i.e., N basis points over Euribor) of floating-rate bonds, making the estimate of the cost of the interest of these bonds impossible when the Euribor used as reference rate changed. On the other hand, fixed-rate bonds are more sensitive to fluctuations of interest rate as evidenced by the amount of fixed-to-floating interest rate swap used by LGs to improve the costs of liabilities by the debt position [

30].

Additionally, a third version of the estimate was performed considering municipal bonds as if they were bank loans. It was carried out by replacing the bond’s interest rate with the maximum bank interest rate. Ceteris paribus, it was possible to draw up the amortizing plan and determine the overall cost of the interest that would have been in the case that the LGs got mortgages instead of issuing bonds. This simulation makes the comparison between them possible because bonds and bank loans share the same repayment scheme [

10,

11].

The qualitative approach employed a preliminary documentary analysis covering relevant national legislation and official documentation issued by the MEF and Cassa Depositi e Prestiti. Besides this, a series of semi-structured interviews with leading actors of the public financial management sector was conducted. The first round of interviews was conducted in 2015, including a manager in charge at the Directorate of Public Debt at the MEF and a questionnaire via email attended by the six heads of finance of the LGs involved in the 2015 Italian regional government bond buyback. This question-and-answer session was aimed at understanding the Italian Central Government’s rationale for the intervention in local finance and the characteristics of LGs debt. In particular, the questionnaire was concerned with the rationale for municipal bond issuing, their specific traits, and the conditions of derivatives signed at the issuance; as well as whether measures of the Domestic Stability Pact were in place and how these limited the issuance of bonds. The second round of interviews took place between 2019 and 2020 by calling on two heads in charge at Cassa Depositi e Prestiti and the Director of the Observatory on Italian Public Accounts. The interviews lasted on average 47 minutes. The interviewees of the second round were informed of the findings of the quantitative stage. Subsequently, they were asked about the consequentiality of the establishment of European fiscal policy. From an epistemological perspective, this qualitative analysis is essential for becoming aware of how the Centralised Discipline and Control Model affects the borrowing system.

5. Results

Since the strategy proposal mixed quantitative and qualitative approaches to address the main research questions, the results from the two approaches are presented separately in this section and then subsequently integrated for the discussion.

5.1. Quantitative Analysis and Findings

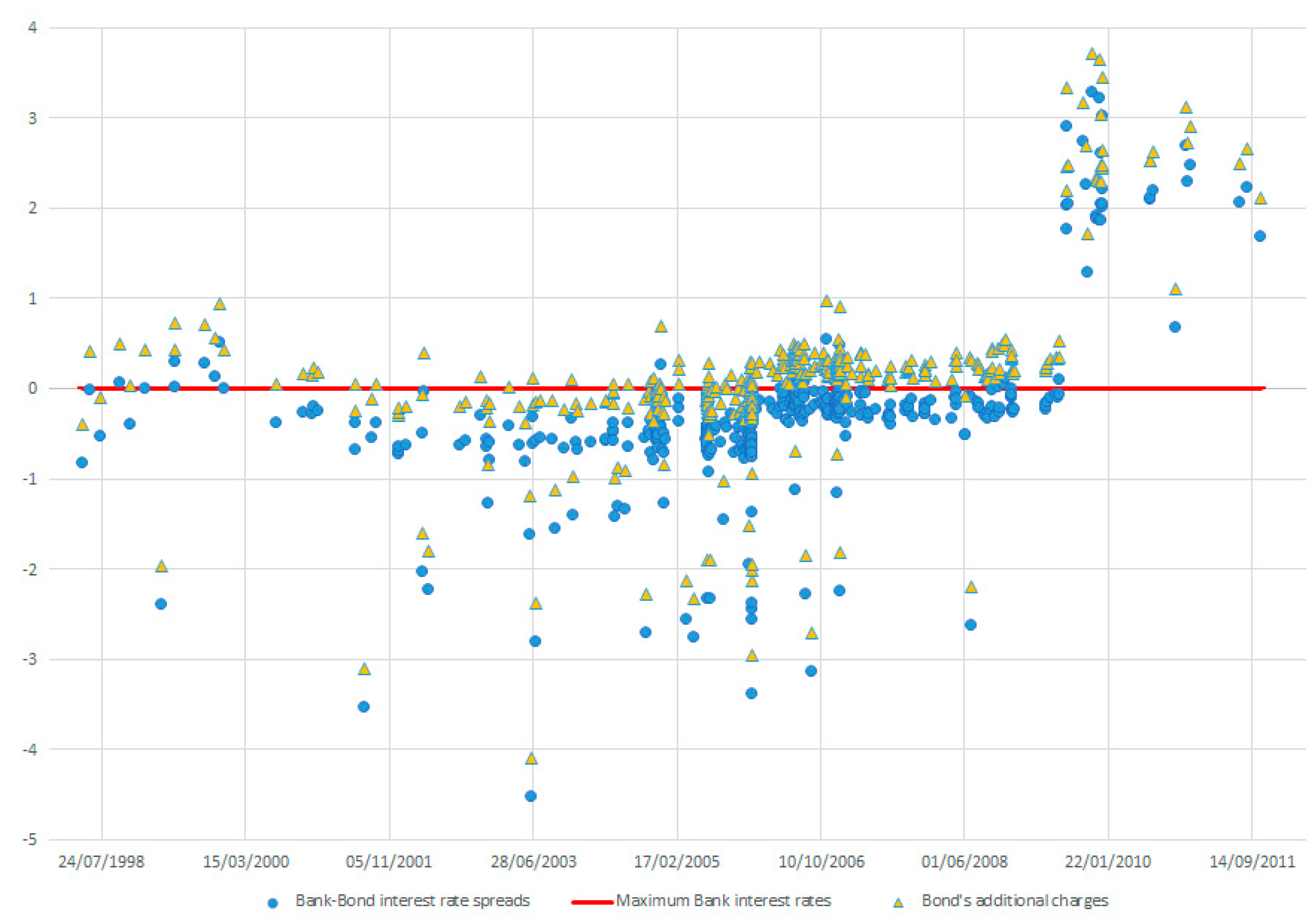

The repayment plan of 519 fixed-rate municipal bonds considered for the study was in constant instalments. As envisaged by the French depreciation method, while the share of interest decreases, the principal increases over time. This allows for the determination of the exact amount of bonds’ interests. Besides, the French depreciation method is also used by banks to draw up loans’ amortization plans. Accordingly, it allows for the determination of the exact amount of loans’ interests, too. Data used to carry out the comparison are the same for both the financial tools, except for the interest rate. The reference rates for municipal bonds are the interest rates reported in the CEAM dataset. The applicable interest rates for bank loans are periodically determined by the Minister of the Treasury, indicating the maximum rates for loans to LGs. The spreads between them are shown in

Figure 1.

In

Figure 1, each blue dot represents a municipal bond issued. Their visualization is in chronological order from 1996 until the end of 2011. In contrast, the red line represents the maximum interest rates to which LGs could borrow from banks and serves as a reference to assess municipal bonds. The distance of points from the red line is the deviation from the maximum bank interest rates. The points above zero represent positive spreads and correspond to extra costs when selecting a bond. The figure shows a narrowing of the gap of interest rates between municipal bonds and bank loans, after which the spreads widen and become positive since 2009. Approximately 11 percent of issued bonds lie beyond the red line. However, it was estimated [

36] that the emission rate of those bonds should be increased by 0.4282% to consider the emissions and management charges not envisaged for bank loans. In

Figure 1, each yellow triangle represents a municipal bond increased with these expenses.

As a consequence, roughly 56 percent of issued bonds lie beyond the red line. There is indeed a grey area where it is difficult to understand whether bonds cost more than the equivalent bank loan.

By drawing up the amortizing plan, it was possible to determine the overall cost of each municipal bond’s interest. For this purpose, the amortization schedule was filled with financial data (amount, annual interest rate, maturity, number of instalments per year, date of issuance) of the bonds. It provided the cost for interest as output. The fiscal aspects were considered in the draft of the amortization plan so that the value of tax retrocession was deducted from the amount of each instalment up to 2006. To simulate the overall cost of the interest if bonds would have been loans, the bond’s interest rate was replaced with the maximum bank interest rate in the amortization schedule. The overall results of this comparison are summarised in

Table 2, which reports the costs in terms of interests expressed as percentages of the borrowing amounts.

In general,

Table 2 shows that bank loans and bonds’ costs were roughly comparable, but bonds had a slightly higher variance, resulting in a highest cost at the top. Two hundred and eighty-one out of 519 bonds were revealed to be more expensive than the banking alternative, costing on average 6.67 percent more. However, it should be borne in mind that several of those bonds were issued when LGs were entitled to receive back part of the revenues from taxes paid by bondholders, which was a compensation measure that allowed LGs to cut down the overall cost of bonds. Therefore, the third column of

Table 2 describes the hypothesis that the tax retrocession’s revision had not carried out. To produce these results, the value of tax retrocession was deducted from each instalment amount until maturity. In this case, the figures indicate that bonds would have been the cheapest funding method. If the tax retrocession were still in force, bonds would cost 56.61 percent less. These findings indicate that the tax retrocession reduced the cost of funding for LGs that issued bonds. The fiscal framework changes precluded the competitive advantage of bonds compared to bank loans, meaning municipal bonds are no longer suited for LGs.

5.2. Qualitative Analysis and Findings

According to the LGs’ heads of finance, who took part in the questionnaire, for a decade since bonds’ inception in LG borrowing system, they were an effective funding method because of the conditions offered by the capital market that were better than the mortgage market. Respondents disclosed that municipal bonds were issued considering the tax retrocession benefit that cut down their overall cost. Municipal bonds were so cost-efficient for servicing public sector debt that the heads of finance also indicated the lower risk associated with municipal bonds compared to other funding methods. Indeed, there were no Domestic Stability Pact measures in force against municipal bonds at the time of their issuance. This scenario changed in 2006 when the abolition of tax retrocession caused the cost of municipal bonds to rise, making them no longer economically feasible. According to Dr. Maisto—Head of Territorial Institutional Affairs at Cassa Depositi e Prestiti—the rationale for municipal bond issuing was almost exclusively to take advantage of the fiscal benefit. Until the tax retrocession was in place, LGs paid less attention to high-interest rates applicable at that time. Municipal bonds became suddenly risky and costly for LGs’ budgets due to the withdrawal of tax retrocession benefits. As the Director of the Observatory on Italian Public Accounts observed,

“The withdrawal of tax retrocession benefit belongs to those measures to move back resources to the center. In a monetary union it is vital to have superordinate rules to avoid single countries to unbalance the entire area. This justifies the Centralised Discipline and Control Model.”

(Dr. Cottarelli)

The scenario worsens even more with the adoption at the local level of the Stability and Growth Pact rules that imposed further limits to indebtedness that changed the municipal bond market permanently. Those costs cuts no longer compensated the risks posed by the derivatives signed at the time of issuance of municipal bonds. Since 2008 the Central Government has prohibited LGs from underwriting new derivatives and LGs could not renegotiate their bonds. In fact, derivatives have to be traded simultaneously with the underlying debt.

As made clear by the manager in charge at the Directorate of Public Debt at the MEF,

“The situation has been crystallised to prohibitive conditions because these issuings have been made during a context of much higher interest rates than the presents. In fact, notwithstanding LGs bear the expensive contractual terms of operations made years before, they are unable to renegotiate these expensive bonds.”

(Dr. Tesseri)

A further consequence of the decision to prevent derivatives is that funding LGs is no longer profitable for commercial banks that left the market. In early 2000 global banking giants funded Italian LGs, but now not even Italian banks do so. Banks mounted the operation upon derivatives and hedging strategies. Everything was played under the assumption that the upfront attracted LGs being liquid cash. LGs then repaid it with interests.

Nowadays, LGs are prevented from renegotiating their bonds unless they alienate some assets. However, this solution causes asymmetries among LGs. For example, the 2015 bond buyback was funded through a state mortgage and the concurrent disposal of assets, namely the derivatives with positive mark-to-market values. In this operation, the overall cost only fell when the mark-to-market values were positive, and so the level of public debt was reduced. On the contrary, the derivatives with negative mark-to-market values would have increased the operational cost, and so the level of public debt increased as well. Thus, the LGs that did not meet the conditions and received an unfavourable assessment of their derivatives were excluded from the operation [

33].

To summarize, (1) the Central Government, to prevent new local debt and control the existing debt, revoked the benefit of tax retrocession making municipal bonds no longer cost-efficient and then (2) prevented LGs from entering new derivatives to hedge new municipal bonds; this led to (3) the banks abandoning the market. A possible solution to this puzzle is that the Central Government takes the place of bondholders as creditor and cuts down the costs of servicing public sector debt. This would be highly disempowering for LGs and would involve technical and political issues that are relatively difficult to resolve, with any such modifications perhaps leading to considerable political conflict between the state and LGs. In this case, it is the state that in turn would borrow to lend to LGs via mortgage granted directly or indirectly through its specialty municipal banks.

As Dr. Mancini—Head of South Italy Coverage for Public Administrations at Cassa Depositi e Prestiti—made clear, Cassa Depositi e Prestiti’s market share is currently about 95% (around 135,000 loans granted to LGs). This is because it has an institutional role that makes it possible to renegotiate, lengthening the maturity of the outstanding debt while respecting the principle of financial equivalence (see

Appendix A). The methodology allows us to find out the interest rate to use for the renegotiation. The present value of the new amortization plan’s instalments is equal to the present value of the instalments of the old amortization plan. Renegotiations compliant with the principle of financial equivalence are unlikely to be carried out by banks because they would cause losses in their financial statements. For example, the agreement recently concluded by the Italian Banking Association (ABI) for the suspension of payment of the share of principal in the instalments owed by LGs has been revised because it led to distracting the principle of cost-effectiveness of LGs’ financial operations.

“It is true that Cassa Depositi e Prestiti has a central role but actually it is true even in other countries. Within the European context the LGs’ debt is not really parcelled due to the banking crisis the public sector has been abandoned as not appealing. The centralising of debt is a matter of investment risks and returns.”

(Dr. Maisto)

Occasionally the Central Government can also decide to pay LGs debt without complying with the principle of financial equivalence. This kind of operation is possible for the state because the national budget could run a deficit. The maturity of the outstanding debt could be extended, and the interest rate could be reduced. Still, the actuarial compensation that holds the principle of financial equivalence could not be considered. For example, this arrangement has been implemented to renegotiate the so-called Mutui MEF, which were mortgages granted directly by the Ministry whose accounts were disjoined from the National budget and re-recorded at a lower rate.

“The contract for the Mutui MEF does not provide for the clause of the actuarial compensation. LGs can merely pay out the remaining capital of the old mortgage which ceases to exist free of charges”

[Dr. Mancini]

”The attached conditions are favourable for LGs but there is someone who loses, that is the State which takes a financial loss. LGs have a limited financial autonomy that limits its capacity to borrow. The centralising of debt is a consequence of how autonomous LGs are and therefore it is matter of legal framework.”

(Dr. Maisto)

6. Discussion

The Centralised Discipline and Control Model may be considered the outcome of the post-New Public Management reforms, which resulted in enhanced political control and a re-centralization process [

37], leading to fiscal constraints associated with the Stability and Growth Pact. Its introduction may have restricted the use of bonds, besides controlling municipal borrowing decisions [

3], thus undermining LGs’ financial autonomy. The model “reaffirmed the key role of traditional cameralistic accounting, whose main purpose has always been to centrally control government spending” [

21] (p. 11). This paper highlighted the existence of hidden costs for LGs that underwent the Centralised Discipline and Control Model. Accordingly, Hypothesis H1 is confirmed. The evidence collected shows how the Italian Central Government affected the local borrowing system, making it unfavourable to municipal bonds issuing and to private banks. Therefore, Hypothesis H2 is confirmed as well. The Central Government set up an expensive system for controlling the entire public sector debt. Banks were no longer interested in operating in this market, so the specialty municipal bank took it (almost) all. The Central Government had the incentive to incur costs to supervise the LGs’ budgetary process, avoid the misuse of their borrowing powers, and prevent financial distress. Still, the lower cost of debt has not offset these monitoring costs. These findings contrast with Marks and Raman [

5], who suggest that “State supervision is systematically associated with lower borrowing costs”. This paper showed instead that this assertion might not be true. The legal framework in which Italian LGs operate made municipal bonds an unfeasible alternative to borrowing from banks. Similarly, the ban on derivatives made the market unprofitable for private banks. Adopting the Eurozone financial sustainability requirements into the Italian legal framework generated hidden costs shared between LGs and the Central Government. The credit market is heavily dependent on the legal and regulatory framework [

38].

However, these results are more robust for unitary countries than for federations because the level of autonomy of LGs appears to be associated with the degree of development of the sub-national debt market, which is small among the unitary structured countries. Our findings indicate that the Central Government’s intervention restricted the financial autonomy of LGs in Italy by shrinking the credit market. The situation is similar in France [

39], another unitary EU country; despite the decentralization process undertaken in the country, the Central Government is still strongly involved in LGs’ financial affairs. While the possibility to borrow from the market has been conceded to LGs with the General Code for Territorial Communities, when their operating budget and the investment budget are balanced, in 2010 the Central Government revoked an important a sub-national tax (the tax professionelle) to keep the consolidated budget balanced. As a result, nowadays, French LGs have limited financial autonomy and do not directly borrow from the market but do so residually through banks. The resources now flow into LGs’ budgets as transfers by the central government, which also bear the borrowing costs even if they are meant to breach the limits of European fiscal rules.

By contrast, a recent literature review [

4] based on a more federalist state (such as Spain) suggests that adopting the Stability and Growth Pact measures left a greater borrowing autonomy to LGs. The implementation of European fiscal regulation into the Spanish domestic framework has been realized with the adoption of financial thresholds that do not exclude the chance for LGs to borrow from banks and markets while respecting the generally accepted concepts of financial sustainability, solvency, and liquidity. Interestingly, the Spanish approach is quite similar to that in the United Kingdom, where the Prudential Borrowing Framework has been adopted to respond to the devolution of borrowing powers to LGs. The Prudential Borrowing Framework is an example of the Professional Discipline and Control Model. As Bailey et al. [

6] evidenced, the Centralised Discipline and Control Model existed in the United Kingdom until 2004. Before the adoption of the Prudential Borrowing Framework, LGs had to meet severe financial limits imposed by the Central Government, which had a detrimental effect on their freedom and flexibility. The Professional Discipline and Control Model grants a significant degree of freedom and flexibility to determine the capital expenditures of LGs, through the use of Prudential Indicators, while ensuring compliance with the balanced-budget rule. These indicators allow sustainability and prudence in LGs’ accounts and transcend the Centralised Discipline and Control Model’s limitations.

Similarly, the solution adopted in Germany [

40,

41] overcomes the limitations of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model. Recalling the Market Discipline and Control Model [

42], the Föderalismusreform II introduced the debt brake rule conceived in Switzerland. The mechanism aims at financing expenditures through current revenues instead of new debt. However, differently from the Swiss LGs that decided on their own to adopt the fiscal rule to enhance their credit standing in the market, the setup in Germany has been negotiated between the different layers of government and LGs still enjoy borrowing autonomy. The debt brake applies to the Bund and the Länders (starting from 2020) but does not affect LGs.

7. Conclusions

Policy makers should pay particular attention to which model of control to implement by considering their country’s specific characteristics and the potential impacts of the different models on them, according to the present economic circumstances. The choice of control model should consider the trade-off between economic efficiency, equity, and stability, whose balance may vary across countries and over historical moments [

43]. The different impacts of the Centralised Discipline and Control Model on countries with different institutional settings, despite belonging to the European Union, may push unitary states toward a paradigm shift, as in the United Kingdom. During tough economic times, the need for close supervision exceeds the appeal of autonomy, and therefore, the Centralised Discipline and Control Model is deemed appropriate. However, as this paper shows, hidden costs may appear in these cases. On the contrary, in more relaxed economic circumstances, the Professional Discipline and Control Model should be appropriated because it allows for sustainability and prudence in LGs’ accounts and transcends the Centralised Discipline and Control Model’s limitations [

6].

This paper has some limitations: First, it is based on a single country case, though an interesting one due to the size of both the debt and the market. Second, floating-rate emissions have been left out from the analysis to make the comparison between bonds and bank-debt more robust. Future research could consider replicating the bank-bond comparison proposed in this paper in other countries. For example, the shift to the Market Discipline and Control Model in unitary states would not ensure that the costs for LGs would be less than the costs they are paying under the Centralised Discipline and Control Model. This depends on the maturity of financial markets, which is not the case for European unitary countries [

14,

39], and would require the adoption of accountability mechanisms such as those adopted by LGs in the United States and Switzerland, where voters decide about the sustainability of debt through referendum [

8].