The Effect of Trust on the Various Dimensions of Climate Change Attitudes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Climate change beliefs—climate concern;

- Personal responsibility in connection with the reduction of climate change;

- Support of policy measures in connection with climate change.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Climate Change Attitude—Sociodemographic and Value-Based Investigations

2.2. Trust and Climate Change

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

- Creating a comprehensive theoretically grounded cross-European dataset of public attitudes to climate change, energy security, and energy preferences;

- Getting insights about how national-level socio-political, economic, and environmental factors shape public attitudes to energy and climate change across Europe;

- Examining the role of socio-political values and other individual-level factors in European attitudes to energy and climate change;

- Examining the relative importance of both individual-motivational factors and national circumstances in public preferences for different energy supply sources and demand reduction.

3.2. Beliefs in Connection with the Fact of Climate Change and Climate Concern

3.3. Personal Responsibility in Connection with the Reduction of Climate Change

3.4. Support of Policy in Connection with Climate Change

3.5. Trust

- “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” (0—“You can’t be too careful”; 10—“Most people can be trusted”).

- “Do you think that most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would they try to be fair?” (0—“Most people would try to take advantage of me”; 10—“Most people would try to be fair”).

- “Would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful or that they are mostly looking out for themselves?” (0—“People mostly look out for themselves”; 10—“People mostly try to be helpful”).

3.6. Sociodemographic Variables

- Gender (1 = male, 2 = female).

- Age (four age groups were created: 1 = 16–29 years, 2 = 30–44 years, 3 = 45–64 years, 4= over 65 years).

- Education (1 = up to elementary school, 2 = secondary qualification, 3 = higher education qualification).

- Income (0 = finding it difficult on present income, 1 = living comfortably on present income).

3.7. Analytical Methods

4. Results and Discussion

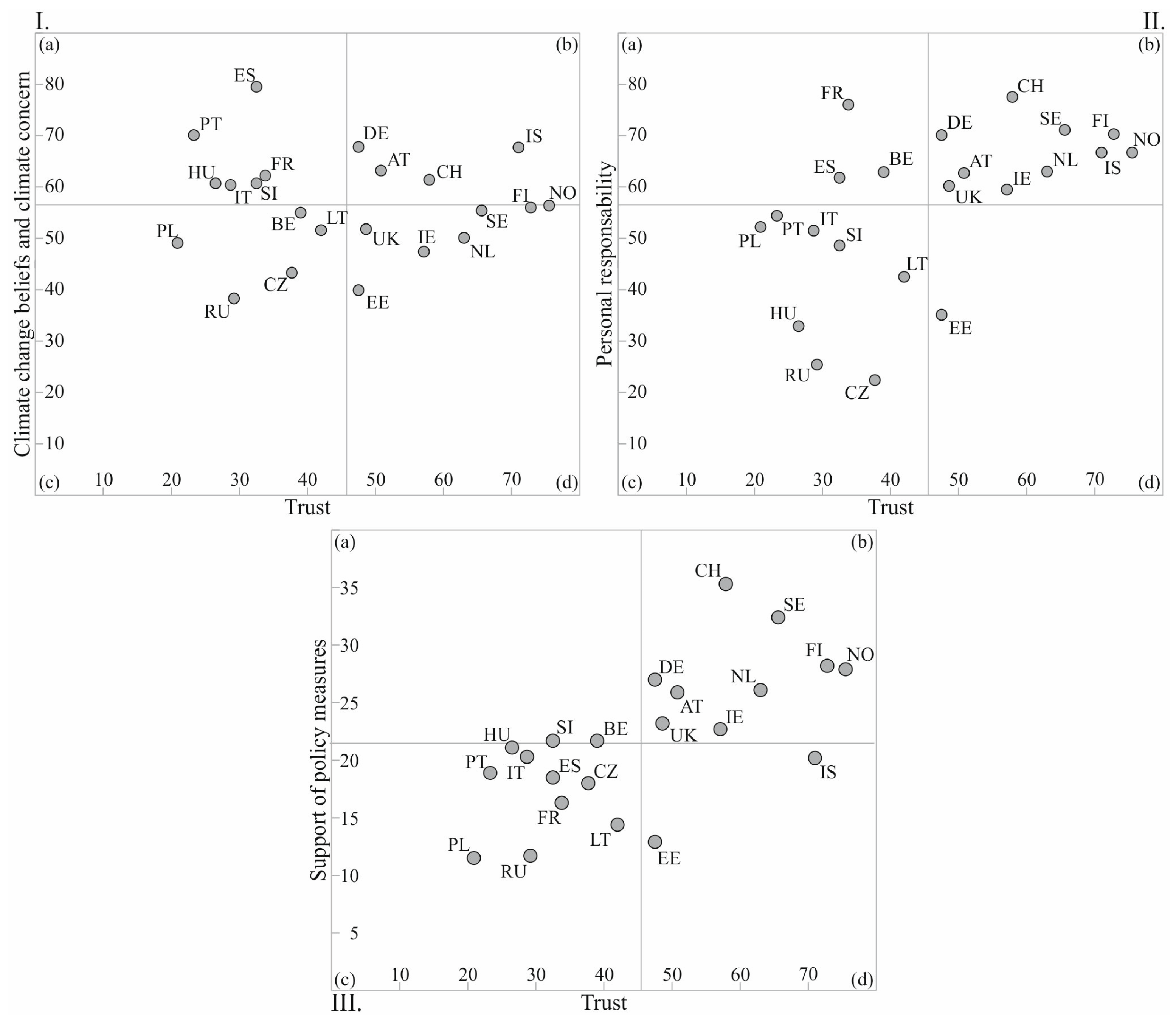

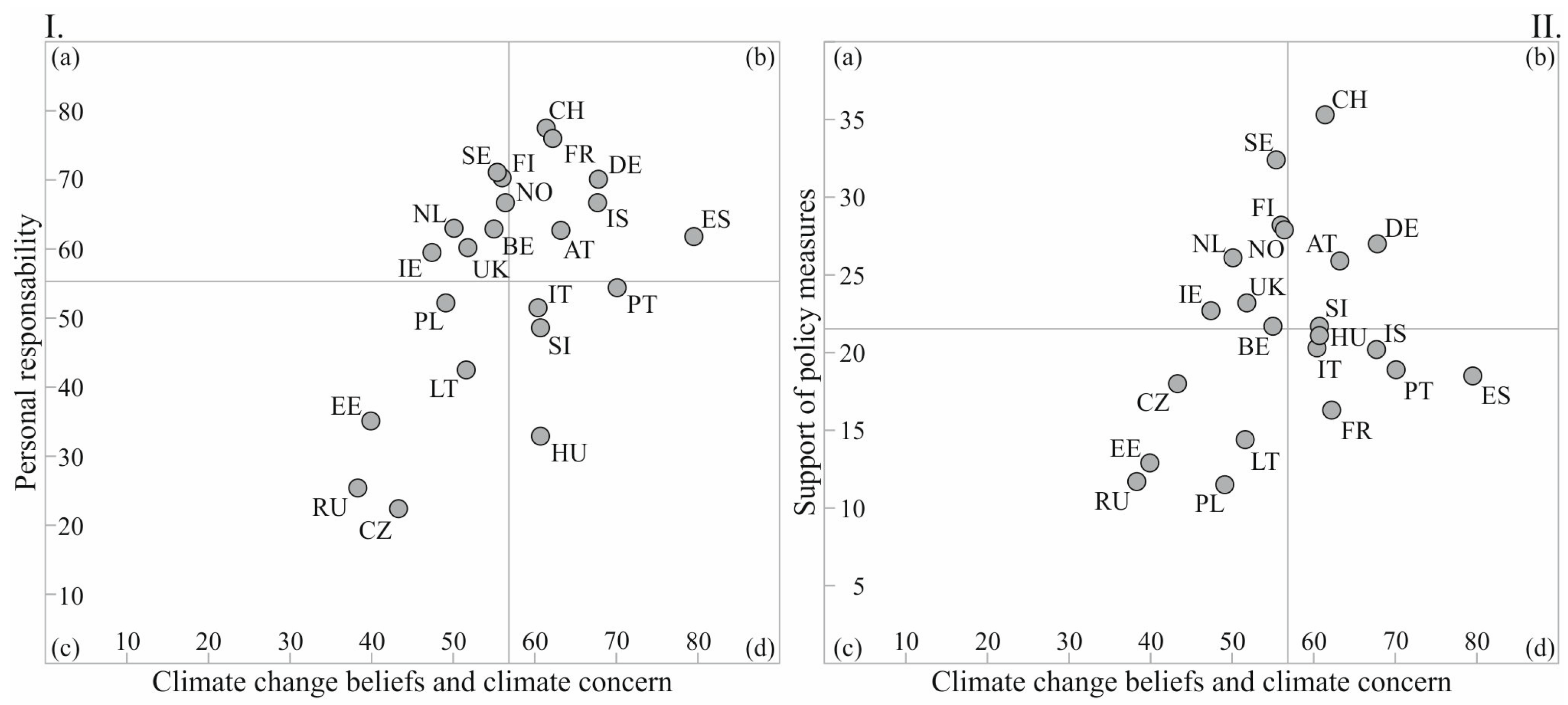

4.1. Attitude to Climate Change and Trust

4.2. The Relationships between Trust and Attitude to Climate Change

4.2.1. The Relationships between Trust and Climate Attitude at the Level of the Individual

4.2.2. The Relationships between Trust and Climate Attitude in Various Regions in Europe—Macro-Level Analysis

4.2.3. The Role of Trust in Overcoming the Gap between Climate Concern and Action

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Footprint Network. Available online: https://www.overshootday.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- European Commission. A Resource-Efficient Europe—Flagship Initiative under the Europe 2020 Strategy. 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0021:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Dunlap, R.E.; Gallup, G.H.; Gallup, A.M. Of global concern: Results of the health of the planet survey. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 1993, 35, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Mayer, A. A social trap for the climate? Collective action, trust and climate change risk perception in 35 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 49, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Politics of Climate Change Polity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-745-65514-7. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, K.M. Climate Denial: Emotion, Psychology, Culture, and Political Economy. In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; Dryzek, J.S., Norgaard, R.B., Schlosberg, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 399–413. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzoli, A.; Szilágyi, D.; Bán, A. Climate Vulnerability Regarding Heat Waves—A Case Study in Hungary. Deturope 2018, 10, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Nicholson-Cole, S.; Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P.; Chan, H.W. Generalized trust narrows the gap between environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevä, I.J.; Kulin, J. A Little More Action, Please: Increasing the Understanding about Citizens’ Lack of Commitment to Protecting the Environment in Different National Contexts. Int. J. Sociol. 2018, 48, 314–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbe, J.; Pahlahl–Wostl, C. A methodological framework to initiate and design transition governance processes. Sustainability 2019, 11, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Social Survey. ESS Round 8 Module on Climate Change and Energy—Question Design Final Module in Template ESS; ERIC: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, M.; Sevä, I.J.; Kulin, J. Political trust and the relationship between climate change beliefs and support for fossil fuel taxes: Evidence from a survey of 23 European countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Koch, M. Public Support for Sustainable Welfare Compared: Links between Attitudes towards Climate and Welfare Policies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazen, A.; Vogl, D. Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaløy, B.; Finseraas, H.; Listhaug, O. The publics’ concern for global warming: A cross-national study of 47 countries. J. Peace Res. 2012, 49, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, T.S.; Qian, H.; Houser, K.M.; McCright, M.A. Climate Change Views, Energy Policy Preferences, and Intended Actions Across Welfare State Regimes: Evidence from the European Social Survey. Int. J. Sociol. 2019, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, B.; Booth, K. Skepticism in a Changing Climate: A Cross-National Study. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 33, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H2020 REPAiR Project Reports. Available online: http://h2020repair.eu/project-results/project-reports/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainable transitions: Responses to seven criticism. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiatu, S. A review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.; Upham, P. International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Milojev, P.; Greaves, L.M.; Sibley, C.G. Socio-structural and psychological foundations of climate change beliefs New Zealand. J. Psychol. 2015, 44, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga, W.; Spence, A.; Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S.; Pidgeon, N.F. Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Visschers, V.H.M.; Siegrist, M.; Arvai, J. Knowledge as a driver of public perceptions about climate change reassessed. Nat. Clim Chang. 2016, 6, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Scepticism and uncertainty about climate change: Dimensions, determinants and change over time. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Kasser, T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 74, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Markowitz, E.; Pidgeon, N. Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D.M.; Jenkins-Smith, H.; Braman, D. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J. Risk Res. 2011, 14, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, Environmental Concern, and Environmental Behaviour: A Study into Household Energy Use. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990; ISBN 069107786X. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theory and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psy. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, M. The Logic of Collective Action; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; ISBN 0674537513. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A multi-scale approach to coping with climate change and other collective action problems. Solutions 2010, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bohr, J. Barriers to environmental sacrifice: The interaction of free rider fears with education, income, and ideology. Sociol. Spectr. 2014, 34, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularska-Kucharek, M.; Bzeziński, K. The economic dimension of social trust. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2016, 23, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Consequences of Modernity Polity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780804718912. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka, P. Trust: A Sociological Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U.; Giddens, A.; Lash, S. Reflexive Modernization. Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order Polity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; ISBN 9780804724722. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R. Trust. Key Concepts Series; Polity Press: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9780745624648. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R. Conceptions and Explanations of Trust. In Trust in Society; Cook, K.S., Ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 3–39. ISBN 9780871541819. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order; Free Press Paperback: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 1439107475. [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov, D. Trust as a Process: A Three-Dimensional Approach. Sociology 2007, 41, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as a Social Reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E.M. The Moral Foundations of Trust; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; ISBN 9780521011037. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmstrof, S. The Climate Sceptics Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Available online: http://www.pik-potsdam.de/~stefan/Publications/Other/rahmstorf_climate_sceptics_2004.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Algan, Y.; Cahuc, P. Trust and Growth. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2013, 5, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, C.M.; Lanier, K.; Meer, S. Attitudinal and Behavioral Measures of Trust: A New Comparison; Emory University Department of Economics: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2008; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.707.6292&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Fehr, E.; Fischbacher, U.; von Rosenbladt, B.; Schupp, J.; Wagner, G.G. A Nation-Wide Laboratory. Examining Trust and Trustworthiness by Integrating Behavioral Experiments into Representative Surveys. J. Appl. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2002, 122, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gächter, S.; Herrmann, B.; Thöni, C. Trust, Voluntary Cooperation, and Socio-economic Background: Survey and Experimental Evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 55, 505–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Laibson, D.; Scheinkman, J.; Soutter, C. Measuring Trust. Q J. Ecol. 2000, 115, 811–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.S.; Mitamura, T. Are Surveys on Trust Trustworthy? Soc. Psychol. Q. 2003, 66, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, P.; Smith, P. Assessing the Validity of Generalized Trust Questions: What Kind of Trust are We Measuring? Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2010, 22, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeskens, T.; Hooghe, M. Cross-cultural Measurement Equivalence of Generalized Trust. Evidence from the European Social Survey 2002 and 2004. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torpe, L.; Lolle, H. Identifying Social Trust in Cross-country Analysis: Do We Really Measure the Same? Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 103, 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U.; Stern, P.C. Public understanding of climate change in the United States. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trend | Attribute | Impact | Concern | Composite Indicator | Composite Indicator 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | ||||||||

| Austria | n = 2010 | 92.5 | 90.9 | 74.0 | 78.0 | 63.2 | 61.0 | 65.4 |

| Belgium | n = 1766 | 96.4 | 93.7 | 66.4 | 80.9 | 55.0 | 52.6 | 57.3 |

| Switzerland | n = 1525 | 96.4 | 94.3 | 74.0 | 78.4 | 61.4 | 58.9 | 63.9 |

| Germany | n = 2852 | 95.5 | 94.6 | 77.4 | 86.6 | 67.8 | 66.0 | 69.5 |

| France | n = 2070 | 96.3 | 93.4 | 73.7 | 81.0 | 62.2 | 60.1 | 64.4 |

| United Kingdom | n = 1959 | 93.6 | 90.7 | 66.0 | 71.5 | 51.8 | 49.5 | 54.0 |

| Ireland | n = 2757 | 96.1 | 91.0 | 63.2 | 68.6 | 47.4 | 45.4 | 49.3 |

| Netherlands | n = 1681 | 96.3 | 91.6 | 61.6 | 76.1 | 50.1 | 47.6 | 52.5 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | ||||||||

| Czechia | n= 2269 | 88.9 | 87.7 | 68.0 | 57.7 | 43.3 | 41.1 | 45.5 |

| Estonia | n = 2019 | 91.3 | 88.2 | 59.8 | 58.0 | 39.9 | 37.7 | 42.1 |

| Hungary | n = 1614 | 91.4 | 92.2 | 77.0 | 78.4 | 60.7 | 58.1 | 63.2 |

| Lithuania | n = 2122 | 88.7 | 82.1 | 73.7 | 67.9 | 51.6 | 49.2 | 53.9 |

| Poland | n = 1694 | 92.6 | 89.2 | 70.4 | 66.5 | 49.1 | 46.5 | 51.6 |

| Russian Federation | n = 2430 | 82.2 | 78.1 | 61.8 | 64.3 | 38.3 | 35.9 | 40.6 |

| Slovenia | n = 1307 | 96.5 | 92.8 | 71.4 | 83.8 | 60.7 | 58.0 | 63.4 |

| Southern Europe | ||||||||

| Spain | n = 1958 | 95.8 | 95.4 | 87.9 | 88.3 | 79.5 | 77.6 | 81.3 |

| Italy | n = 2626 | 94.8 | 93.4 | 68.9 | 84.4 | 60.4 | 58.4 | 62.4 |

| Portugal | n = 1270 | 97.0 | 93.4 | 81.2 | 86.7 | 70.1 | 67.5 | 72.7 |

| Northern Europe | ||||||||

| Finland | n = 1925 | 94.0 | 93.9 | 67.2 | 79.1 | 56.0 | 53.7 | 58.2 |

| Iceland | n = 880 | 97.7 | 94.6 | 81.5 | 77.9 | 67.7 | 64.5 | 70.8 |

| Norway | n = 1545 | 92.9 | 87.6 | 71.9 | 76.3 | 56.4 | 53.9 | 58.9 |

| Sweden | n = 1551 | 96.8 | 92.4 | 81.3 | 65.1 | 55.4 | 52.8 | 57.9 |

| Responsibility | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | ||||

| Austria | n = 2010 | 62.7 | 60.6 | 64.9 |

| Belgium | n = 1766 | 62.9 | 60.7 | 65.2 |

| Switzerland | n = 1525 | 77.5 | 75.4 | 79.7 |

| Germany | n = 2852 | 70.1 | 68.4 | 71.8 |

| France | n = 2070 | 76.0 | 74.1 | 77.8 |

| United Kingdom | n = 1959 | 60.2 | 58.0 | 62.4 |

| Ireland | n = 2757 | 59.5 | 57.6 | 61.3 |

| Netherlands | n = 1681 | 63.0 | 60.7 | 65.3 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | ||||

| Czechia | n= 2269 | 22.4 | 20.6 | 24.2 |

| Estonia | n = 2019 | 35.1 | 33.0 | 37.2 |

| Hungary | n = 1614 | 32.9 | 30.5 | 35.2 |

| Lithuania | n = 2122 | 42.5 | 40.2 | 44.7 |

| Poland | n = 1694 | 52.2 | 49.7 | 54.7 |

| Russian Federation | n = 2430 | 25.4 | 23.4 | 27.3 |

| Slovenia | n = 1307 | 48.6 | 45.8 | 51.3 |

| Southern Europe | ||||

| Spain | n = 1958 | 61.8 | 59.6 | 64.0 |

| Italy | n = 2626 | 51.5 | 49.5 | 53.5 |

| Portugal | n = 1270 | 54.4 | 51.6 | 57.2 |

| Northern Europe | ||||

| Finland | n = 1925 | 70.3 | 68.3 | 72.4 |

| Iceland | n = 880 | 66.7 | 63.5 | 69.8 |

| Norway | n = 1545 | 66.7 | 64.3 | 69.0 |

| Sweden | n = 1551 | 71.1 | 68.8 | 73.3 |

| Fossil | Renewable | Banning | Composite Indicator | Composite Indicator 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | |||||||

| Austria | n = 2010 | 33.8 | 84.6 | 64.8 | 25.9 | 23.9 | 27.8 |

| Belgium | n = 1766 | 31.2 | 76.6 | 67.0 | 21.7 | 19.8 | 23.6 |

| Switzerland | n = 1525 | 47.7 | 84.4 | 69.4 | 35.3 | 32.9 | 37.8 |

| Germany | n = 2852 | 38.3 | 85.4 | 69.1 | 27.0 | 25.3 | 28.6 |

| France | n = 2070 | 24.1 | 77.4 | 63.1 | 16.3 | 14.7 | 17.9 |

| United Kingdom | n = 1959 | 37.6 | 69.2 | 56.2 | 23.2 | 21.3 | 25.1 |

| Ireland | n = 2757 | 34.8 | 67.4 | 54.4 | 22.7 | 21.1 | 24.2 |

| Netherlands | n = 1681 | 40.8 | 87.7 | 54.9 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 28.2 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | |||||||

| Czechia | n = 2269 | 29.1 | 61.1 | 58.7 | 18.0 | 16.4 | 19.6 |

| Estonia | n = 2019 | 19.7 | 78.1 | 48.5 | 12.9 | 11.4 | 14.4 |

| Hungary | n = 1614 | 29.9 | 88.9 | 53.5 | 21.1 | 19.0 | 23.2 |

| Lithuania | n = 2122 | 28.8 | 66.1 | 40.6 | 14.4 | 12.8 | 16.0 |

| Poland | n = 1694 | 14.9 | 78.4 | 60.0 | 11.5 | 9.9 | 13.1 |

| Russian Federation | n = 2430 | 23.1 | 59.0 | 41.8 | 11.7 | 10.3 | 13.1 |

| Slovenia | n = 1307 | 29.5 | 90.5 | 65.1 | 21.7 | 19.4 | 24.0 |

| Southern Europe | |||||||

| Spain | n = 1958 | 25.4 | 79.7 | 64.2 | 18.5 | 16.6 | 20.3 |

| Italy | n = 2626 | 26.5 | 72.4 | 67.2 | 20.3 | 18.7 | 22.0 |

| Portugal | n = 1270 | 26.2 | 66.9 | 69.4 | 18.9 | 16.7 | 21.1 |

| Northern Europe | |||||||

| Finland | n = 1925 | 50.7 | 78.7 | 56.6 | 28.2 | 26.2 | 30.2 |

| Iceland | n = 880 | 44.3 | 65.8 | 46.4 | 20.2 | 17.5 | 22.9 |

| Norway | n = 1545 | 48.0 | 85.3 | 49.9 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 30.1 |

| Sweden | n = 1551 | 60.8 | 88.0 | 48.2 | 32.4 | 30.1 | 34.8 |

| Trust | 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe | ||||

| Austria | n = 2010 | 50.8 | 48.6 | 53.0 |

| Belgium | n = 1766 | 39.0 | 36.7 | 41.2 |

| Switzerland | n = 1525 | 57.9 | 55.4 | 60.3 |

| Germany | n = 2851 | 47.5 | 45.7 | 49.4 |

| France | n = 2070 | 33.8 | 31.7 | 35.8 |

| United Kingdom | n = 1959 | 48.6 | 46.4 | 50.8 |

| Ireland | n = 2757 | 57.1 | 55.2 | 58.9 |

| Netherlands | n = 1680 | 63.0 | 60.1 | 65.3 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | ||||

| Czechia | n = 2269 | 37.7 | 35.7 | 39.7 |

| Estonia | n = 2019 | 47.5 | 45.4 | 49.7 |

| Hungary | n = 1612 | 26.5 | 24.4 | 28.7 |

| Lithuania | n = 2122 | 42.0 | 39.9 | 44.0 |

| Poland | n = 1690 | 20.9 | 19.0 | 22.9 |

| Russian Federation | n = 2428 | 29.2 | 27.4 | 31.0 |

| Slovenia | n = 1307 | 32.5 | 30.0 | 35.0 |

| Southern Europe | ||||

| Spain | n = 1956 | 32.5 | 30.5 | 34.6 |

| Italy | n = 2622 | 28.7 | 27.0 | 30.5 |

| Portugal | n = 1269 | 23.3 | 21.0 | 25.6 |

| Northern Europe | ||||

| Finland | n = 1925 | 72.8 | 70.8 | 74.8 |

| Iceland | n = 879 | 71.0 | 68.0 | 74.0 |

| Norway | n = 1544 | 75.5 | 73.3 | 77.6 |

| Sweden | n = 1550 | 65.6 | 63.2 | 67.9 |

| Ideas and Concern | Individual Responsibility | Policy Support | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | OR | p-Value | |

| Western Europe | ||||||

| Austria | 0.990 | 0.916 | 1.627 | 0.000 | 1.320 | 0.001 |

| Belgium | 0.917 | 0.410 | 1.511 | 0.000 | 1.261 | 0.060 |

| Switzerland | 0.883 | 0.281 | 1.774 | 0.000 | 1.362 | 0.009 |

| Germany | 1.167 | 0.067 | 1.500 | 0.000 | 1.195 | 0.042 |

| France | 1.070 | 0.508 | 2.016 | 0.000 | 1.627 | 0.000 |

| United Kingdom | 1.324 | 0.005 | 1.661 | 0.000 | 1.679 | 0.000 |

| Ireland | 0.863 | 0.077 | 1.718 | 0.000 | 1.549 | 0.000 |

| Netherlands | 1.012 | 0.917 | 1.478 | 0.000 | 1.424 | 0.006 |

| Central and Eastern Europe | ||||||

| Czechia | 0.706 | 0.000 | 1,448 | 0.001 | 0.827 | 0.114 |

| Estonia | 0.850 | 0.096 | 1.667 | 0.000 | 1.534 | 0.002 |

| Hungary | 0.940 | 0.614 | 1.357 | 0.014 | 1.306 | 0.067 |

| Lithuania | 0.749 | 0.004 | 1.615 | 0.000 | 1.042 | 0.770 |

| Poland | 1.118 | 0.388 | 1.585 | 0.000 | 1.017 | 0.932 |

| Russian Federation | 1.288 | 0.023 | 2.120 | 0.000 | 0.987 | 0.937 |

| Slovenia | 0.857 | 0.230 | 1.387 | 0.000 | 1.370 | 0.034 |

| Southern Europe | ||||||

| Spain | 0.920 | 0.514 | 1.591 | 0.000 | 1.754 | 0.000 |

| Italy | 0.571 | 0.000 | 1.689 | 0.000 | 1,299 | 0.023 |

| Portugal | 0.907 | 0.530 | 1.455 | 0.011 | 0.902 | 0.573 |

| Northern Europe | ||||||

| Finland | 1.193 | 0.112 | 1.535 | 0.000 | 1.309 | 0.030 |

| Iceland | 1.103 | 0.564 | 2.125 | 0.000 | 1.111 | 0.608 |

| Norway | 1.047 | 0.721 | 1.574 | 0.000 | 1.211 | 0.191 |

| Sweden | 1.188 | 0.138 | 1.718 | 0.000 | 1.349 | 0.018 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bodor, Á.; Varjú, V.; Grünhut, Z. The Effect of Trust on the Various Dimensions of Climate Change Attitudes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310200

Bodor Á, Varjú V, Grünhut Z. The Effect of Trust on the Various Dimensions of Climate Change Attitudes. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310200

Chicago/Turabian StyleBodor, Ákos, Viktor Varjú, and Zoltán Grünhut. 2020. "The Effect of Trust on the Various Dimensions of Climate Change Attitudes" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310200

APA StyleBodor, Á., Varjú, V., & Grünhut, Z. (2020). The Effect of Trust on the Various Dimensions of Climate Change Attitudes. Sustainability, 12(23), 10200. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310200