Mobile Banking: An Innovative Solution for Increasing Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

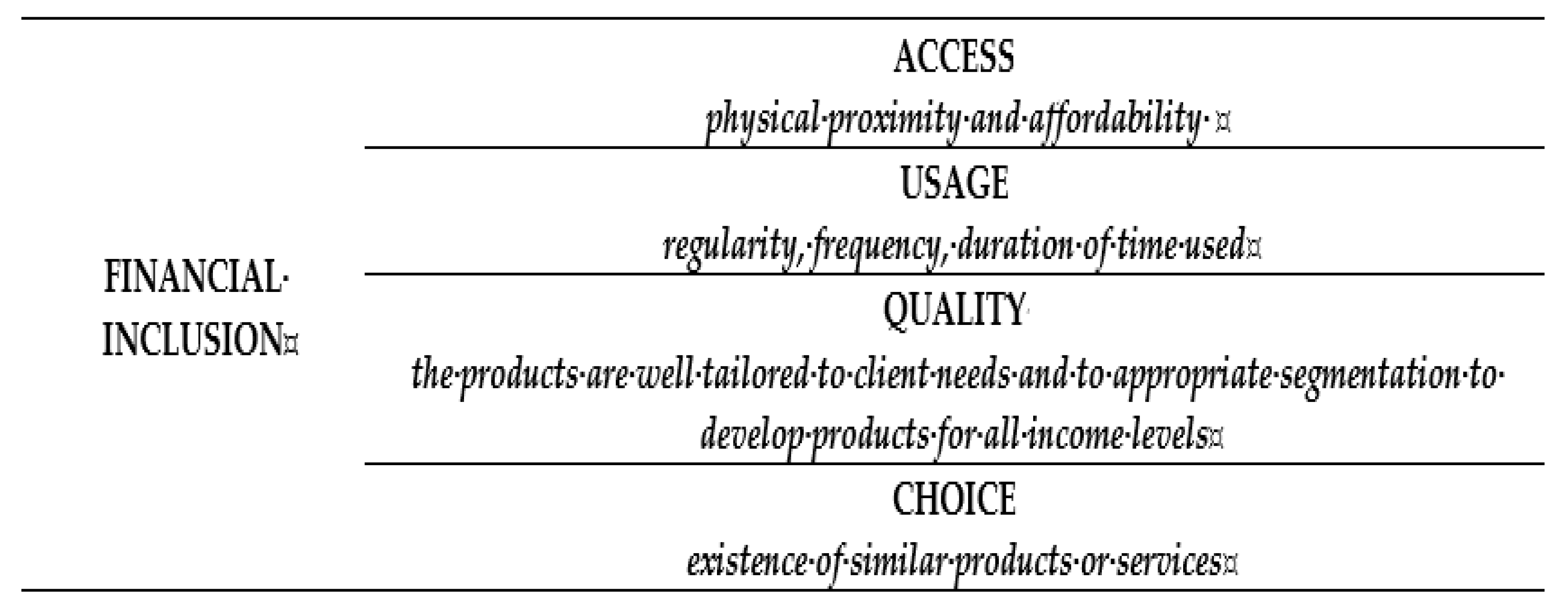

2.1. Financial Inclusion: Definitions and Features

2.2. Barriers to Financial Inclusion

2.3. Drivers of Mobile Banking

3. Methodology

- (1)

- Framing a meta-synthesis exercise: our topic from the outset is framed for a qualitative meta-synthesis exercise.

- (2)

- Locating relevant papers: we searched and located several papers on mobile banking within and outside SSA to gain richer insights on the subject of inquiry.

- (3)

- Deciding what to include: after a literature audit of searched and located papers on mobile banking, we selected those related to mobile banking issues and financial inclusion in SSA in line with the qualitative meta-synthesis tradition.

- (4)

- Appraising studies: the selected papers from SSA were then appraised to draw rich and meaningful information for making informed and evidence-based findings in line with the qualitative meta-synthesis tradition.

- (5)

- Comparing and contrasting exercise: the findings in the selected papers from SSA were compared and contrasted.

- (6)

- Reciprocating translation: we offered an explanation for the similar and opposing findings.

- (7)

- Synthesizing translation: the mixed findings extracted from different papers selected were then fused and synthesised to give a unique explanation for the trends and direction of mobile banking in relation to financial inclusion in SSA.

4. Findings and Discussions

5. Implications, Limitations and Future Research

6. Towards Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Article | Title | Author | Year | Number of Factors Affecting Mobile Banking | Type of Specific Factors Affecting Mobile Banking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toward an Understanding of Behavioural Intention to Use Mobile Banking | Luarn & Lin | 2005 | 3 | Perceived credibility, self-efficacy and financial cost |

| 2 | M-Commerce Implementation in Nigeria: Trends and Issues | Ayo, Ekong, Fatudimu & Adebiyi | 2007 | 4 | Patronage, quality of cell phones, lack of basic infrastructure and security issues |

| 3 | Internet Diffusion in Nigeria: is the ‘Giant of Africa’ waking up? | Muganda, Bankole & Brown | 2008 | 1 | Infrastructure |

| 4 | Mobile Commerce User Acceptance Study in China | Min & Qu | 2008 | 7 | Culture, user satisfaction, trust, privacy protection, quality, experience, and cost |

| 5 | Mobile phone technology in banking system: Its economic effect | Anyasi & Otubu | 2009 | 3 | Convenience, accessibility and affordability. |

| 6 | An Empirical Investigation of the Level of Users’ Acceptance of E-Banking in Nigeria. | Oni, Aderonke & Ayo | 2010 | 6 | Convenience, ease of use, time saving, privacy, appropriateness for their transaction needs, and network security |

| 7 | Mobile phones and economic development in Africa | Aker & Mbiti | 2010 | 3 | Ease of use, fast services and reduced communication costs |

| 8 | Mobile banking adoption in Nigeria | Bankole, Bankole & Brown | 2011 | 1 | Cultural Values |

| 9 | An exploratory study on adoption of electronic banking: underlying consumer behaviour and critical success factors: case of Nigeria | Aliyu, Younus & Tasmin | 2012 | 6 | Accessibility, reluctance to change, cost/price, security concern, ease of use, and awareness |

| 10 | Going cashless: Adoption of mobile banking in Nigeria | Njoku & Odumeru | 2013 | 7 | relative advantage, complexity, compatibility, observability, trialability, age and educational background |

| 11 | Global financial development report 2014: Financial inclusion | World Bank | 2013 | 2 | Economic growth and poverty alleviation |

| 12 | An investigative study on factors influencing the customer satisfaction with e-banking in Nigeria | Balogun, Ajiboye & Dunsin | 2013 | 1 | Quality of the service |

| 13 | Impact of mobile banking on service delivery in the Nigerian commercial banks. | Adewoye | 2013 | 4 | Transactional convenience, savings of time, quick transaction alert and save of service cost |

| 14 | Financial inclusion in Africa | Triki & Faye | 2013 | Broadening access, greater household savings, capital for investment, expansion of class of entrepreneurs, and human capital investment | |

| 15 | The opportunities of digitizing payments | Klapper & Singer | 2014 | 2 | Access and Participation |

| 16 | International remittances and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa | Aga & Peria | 2014 | 1 | Increases the probability of households opening bank accounts |

| 17 | Mobile phone banking in Nigeria: benefits, problems and prospects | Agwu & Carter | 2014 | 4 | Cost of maintenance, Users’ education, poverty and infrastructure availability. |

| 18 | Financial inclusion and innovation in Africa | Beck, Senbet & Simbanegavi | 2015 | 3 | Inclusive growth, financial deepening and access |

| 19 | Financial Inclusion: Can It Meet Multiple Macroeconomic Goals? | Sahay, Cihak, M & N’Diaye | 2015 | 3 | Access to credit, Savings and Economic growth |

| 20 | Can Islamic Banking Increase Financial Inclusion? | Ben Naceur, Barajas & Massara | 2015 | 3 | Access to Islamic banking products, improved savings, investment |

| 21 | User adoption of online banking in Nigeria: A qualitative study | Tarhini, Mgbemena, Trab & Masa’ Deh | 2015 | 3 | Security, religion and culture |

| 22 | The determinants of financial inclusion in Africa | Zins & Weill | 2016 | 4 | Gender, economic status, education and age influence FI |

| 23 | Mobile banking–adoption and challenges in Nigeria | Agu, Simon & Onwuka | 2016 | 5 | Handset operability, Security, Scalability and reliability, Geographic distribution and Age |

| 24 | Financial inclusion in Africa: evidence using dynamic panel data analysis. | Gebrehiwot & Makina | 2016 | 3 | GDP per capita, mobile infrastructure and remoteness |

| 25 | Analysis of the determinants of financial inclusion in Central and West Africa | Soumaré, TchanaTchana & Kengne | 2016 | 9 | Gender, education, age, income, residence area, employment status, marital status, household size and degree of trust in financial institutions |

| 26 | Is the rise of Pan-African banking the next big thing in Sub-Saharan Africa | PWC | 2017 | 2 | Withdrawal of several Western banks and intra-regional trade linkages |

| 27 | Mobile banking in Sub-Saharan Africa: setting the way towards financial development. | Rouse &Verhoef | 2017 | 2 | Extension of remote rural locations and introduction of innovative products |

| 28 | What determines financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa? | Chikalipah | 2017 | 1 | Illiteracy is the major hindrance to FI |

| 29 | Financial inclusion, entry barriers, and entrepreneurship: evidence from China | Fan & Zhang | 2017 | 3 | Mitigation of credit constraints, boosting entrepreneurial activities and reducing information asymmetry in financial transactions |

| 30 | Determinants of financial inclusion in Sub-Sahara African countries | Oyelami, Saibu & Adekunle | 2017 | 2 | Demand side factors (level of income and literacy) and Supply side factors (Interest rate and bank innovation proxy by ATM usage). |

| 31 | An assessment of the impact of mobile banking on traditional banking in Nigeria | Khan & Ejike | 2017 | 4 | Good knowledge of mobile devices, access to mobile banking, convenience and satisfaction of usage |

| 32 | The effect of mobile banking on the performance of commercial banks in Nigeria | Bagudu, Mohd Khan & Roslan | 2017 | 1 | More access to mobile handsets |

| 33 | Financial inclusion as a tool for sustainable development | Voica | 2017 | 3 | Sustainable development, Consumer protection and economic literacy |

| 34 | The effect of financial inclusion on welfare in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from disaggregated data | Tita & Aziakpono | 2017 | 3 | Increase in formal opening of bank accounts, financial infrastructure and economic activities |

| 35 | Infrastructure deficiencies and adoption of mobile money in Sub-Saharan Africa | Mothobi & Grzybowski | 2017 | 2 | physical infrastructure and level of income |

| 36 | Mobile Money and Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa: the Moderating Role of Social Networks | Bongomin, Ntayi, Munene & Malinga | 2018 | 1 | Existence of social networks of strong and weak ties among mobile money users |

| 37 | Can mobile money help firms mitigate the problem of access to finance in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa? | Gosavi | 2018 | 2 | Access to finance, or lines of credit |

| 38 | EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010–2018 survey | EFInA | 2018 | 4 | Number of banked population, awareness & knowledge, institutional exclusion and affordability |

| 39 | The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the FinTech revolution | Demirguc-Kunt, Klapper, Singer, Ansar & Hess | 2018 | 0 | |

| 40 | Financial Inclusion and Per Capita Income In Africa: Bayesian VAR Estimates. | Alenoghena | 2019 | 3 | Per capital incomes, deposit interest rate and the internet |

| 41 | M-PESA and Financial Inclusion in Kenya: Of Paying Comes Saving? | Van Hove & Dubus | 2019 | 2 | Phone owners, Better educated |

| 42 | Migrant remittances and financial inclusion among households in Nigeria. | Ajefu & Ogebe | 2019 | 2 | Receipt of remittances increases the use of formal financial services and migrant networks |

| 43 | The Impact of Mobile Money on the Financial Performance of the SMEs in Douala, Cameroon | Talom & Tengeh | 2019 | 3 | Access to the internet, cost and efficiency |

| 44 | Digitising Financial Services: A Tool for Financial Inclusion in South Africa? | Shipalana | 2019 | 3 | Tackle poverty, promote inclusive development and address the SDGs |

| 45 | See the best Nigerian mobile banking apps in H1 2019 | Benson | 2019 | 2 | Access to mobile device, network connection |

| 46 | Financial Inclusion and Achievements of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Ma’ruf &Aryani | 2019 | 2 | Achievement of SGDs and poverty alleviation |

| 47 | Financial inclusion and sustainable development in Nigeria. | Soyemi, Olowofela & Yunusa | 2019 | 6 | Accessibility, reluctance to change, cost/price, security concern, ease of use, and awareness |

| 48 | Financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa: Recent trends and determinants | Asuming, Osei-Agyei, L.G. & Mohammed | 2019 | 6 | Age, education, gender, wealth, growth rate of GDP and access to financial institutions |

| 49 | Enhancing Financial Inclusion in ASEAN: Identifying the Best Growth Markets for Fintech | Loo | 2019 | 4 | Commercial bank branches, Demand deposit from the rural areas, loan to rural areas and human capital development |

| 50 | Social and Financial Inclusion through Nonbanking Institutions: A Model for Rural Romania. | Yue, Cao, Duarte, Shao & Manta | 2019 | 3 | Access to financial services, communication technologies, digital mobile platforms |

| 51 | Do mobile phones, economic growth, bank competition and stability matter for financial inclusion in Africa? | Chinoda & Kwenda | 2019 | 4 | Mobile phones, economic growth, bank competition and stability impact financial inclusion |

| 52 | Financial Inclusion Condition of African Countries | Chinoda & Kwenda | 2019 | 2 | Access and usage factors affect financial inclusion |

| 53 | Mobile telephony, financial inclusion and inclusive growth | Abor, Amidu & Issahaku | 2019 | 3 | Mobile penetration, pro-poor development and improved livelihoods |

| 54 | Financial Inclusion in Ethiopia: Is It on the Right Track? | Berhanu Lakew & Azadi | 2020 | 3 | Barriers are preference for informal saving club, unemployment and low income |

| 55 | Readiness for banking technologies in developing countries | Berndt, Saunders & Petzer | 2020 | 2 | Access to innovative banking technologies and technology readiness of the people |

| 56 | Financial Inclusion | World Bank | 2020 | 3 | Quality of life, poverty reduction, facilitating investments in health, education, and businesses |

| 57 | Financial exclusion in OECD countries: A scoping review | Caplan, Birkenmaier & Bae | 2020 | 6 | Dominant issues covered in FI are conceptualization, contributors, and impacts of FI. Less covered are measurement, prevention, and contemporary practice trends in financial exclusion. |

| 58 | Financial inclusion-and the SDGs | UN Capital Development Fund | 2020 | 3 | Promotes investment, consumption and resource mobilization |

Appendix B. Year-Wise Distribution of Research Publications

Appendix C. Year-Wise Distribution of Specific Factors Affecting Mobile Banking Explored by Former Publications

References

- United Nations Development Programme Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. 2020. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-8-decent-work-and-economic-growth.html (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- World Bank The World Bank in Africa. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Boso, N.; Debrah, Y.A. Africa rising in an emerging world: An international marketing perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018, 35, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Egbetokun, A.; Osabutey, E.L. Meeting the 21st century challenges of doing business in Africa. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, J.C.; Mbiti, I.M. Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. J. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 24, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, M.; Verhoef, G. Mobile Banking in Sub-Saharan Africa: Setting the Way Towards Financial Development. MPRA Paper No. 78006. 2017, pp. 1–21. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/78006/1/MPRA_paper_78006.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Njoku, A.C.; Odumeru, J.A. Going cashless: Adoption of mobile banking in Nigeria. Niger. Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Raimi, L. Imperative of meta-study for research in the field of corporate social responsibility and emerging issues in corporate governance. In The Handbook of Research Methods on Corporate Social Responsibility; Crowther, D., Lauesen, L.M., Eds.; Handbook Series: Edgar Elgar, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amuda, Y.J.; Embi, N.A.C. Alleviation of Poverty among OIC Countries through Sadaqat, Cash Waqf and Public Funding. Int. J. Trade Econ. Finance 2013, 4, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihugba, O.A.; Odii, A.; Njoku, A. Theoretical Analysis of Entrepreneurship Challenges and Prospects in Nigeria. Int. Lett. Soc. Humanist. Sci. 2014, 5, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjoub, H.; Aga, M.; AbuAlRub, A.; Bein, M.A. Financial Reforms and Determinants of FDI: Evidence from Landlocked Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economics 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuming, P.O.; Osei-Agyei, L.G.; Mohammed, J.I. Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recent Trends and Determinants. J. Afr. Bus. 2019, 20, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongomin, G.O.C.; Ntayi, J.M.; Munene, J.C.; Malinga, C.A. Mobile Money and Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Moderating Role of Social Networks. J. Afr. Bus. 2018, 19, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talom, F.S.G.; Tengeh, R.K. The Impact of Mobile Money on the Financial Performance of the SMEs in Douala, Cameroon. Sustainability 2019, 12, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffie, C.P.K.; Zhao, H.; Mensah, I.A. Panel Econometric Analysis on Mobile Payment Transactions and Traditional Banks Effort toward Financial Accessibility in Sub-Sahara Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankole, F.O.; Bankole, O.O.; Brown, I. Mobile Banking Adoption in Nigeria. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2011, 47, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, C.K.; Ekong, U.O.; Fatudimu, I.T.; Adebiyi, A.A. M-Commerce Implementation in Nigeria: Trends and Issues. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2007, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Muganda, N.O.; Bankole, F.O.; Brown, I. Internet Diffusion in Nigeria: Is the ‘Giant of Africa’ waking up? In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference on World Wide Web Applications, Cape Town, South Africa, 3–5 September 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, E.A. See the Best Nigerian Mobile Banking Apps in H1 2019; Nairametrics Publication: Lagos, Nigeria, 2019; Available online: https://nairametrics.com/2019/07/17/the-best-mobile-banking-apps-in-nigeria/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Chikalipah, S. What determines financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa? Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothobi, O.; Grzybowski, L. Infrastructure deficiencies and adoption of mobile money in Sub-Saharan Africa. Inf. Econ. Policy 2017, 40, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosavi, A. Can Mobile Money Help Firms Mitigate the Problem of Access to Finance in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa? J. Afr. Bus. 2018, 19, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Senbet, L.; Simbanegavi, W. Financial Inclusion and Innovation in Africa: An Overview. J. Afr. Econ. 2015, 24, i3–i11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, K.G.; Makina, D. Financial inclusion in Africa: Evidence using dynamic panel data analysis. In Proceedings of the Conference on Inclusive Growth and Poverty Reduction in the IGAD Region, Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, 24–25 October 2016; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Sahay, R.; Cihak, M.; N’Diaye, P.; Barajas, A.; Mitra, S.; Kyobe, A.; Mooi, Y.; Yousefi, R. Financial Inclusion: Can it Meet Multiple Macroeconomic Goals? Staff. Discuss. Notes 2015, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’Ruf, A.; Aryani, F. Financial Inclusion and Achievements of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in ASEAN. GATR J. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 4, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyemi, K.A.; Olowofela, O.E.; Yunusa, L.A. Financial inclusion and sustainable development in Nigeria. J. Econ. Manag. 2020, 39, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, C. Current Issues Regarding the Protection of Retail Investors on the Capital Market within the European Union. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2017, 17, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, R. Financial Inclusion, Entry Barriers, and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Cerchia, A.E.; Oachesu, M.M.; Udroiu, F. Enhancing Internet Banking-Solutions for Customer Relationship Management. Saudi J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2017, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Voica, M.C. Financial inclusion as a tool for sustainable development. Rom. Econ. Rev. 2017, 44, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Abor, J.Y.; Amidu, M.; Issahaku, H. Mobile Telephony, Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth. J. Afr. Bus. 2018, 19, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovoiu, V.B. An Empirical Analysis of Some Factors Influencing Financial Literacy. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2018, VII, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, M.K.L. Enhancing Financial Inclusion in ASEAN: Identifying the Best Growth Markets for Fintech. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.-G.; Cao, Y.; Duarte, N.; Shao, X.-F.; Manta, O.P. Social and Financial Inclusion through Nonbanking Institutions: A Model for Rural Romania. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakew, T.B.; Azadi, H. Financial Inclusion in Ethiopia: Is It on the Right Track? Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.D.; Saunders, S.G.; Petzer, D.J. Readiness for banking technologies in developing countries. S. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2010, 14, 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sapepa, K.; Roberts-Lombard, M.; Van Tonder, E. The Relationship between Selected Variables and Customer Loyalty within the Banking Environment of an Emerging Economy. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deigh, L.; Farquhar, J.; Palazzo, M.; Siano, A. Corporate social responsibility: Engaging the community. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2016, 19, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deigh, G.L.A. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Banking Sector of a Developing Country: A Ghanaian Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bedfordshire, Luton, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deigh, L.; Palazzo, M.; Farquhar, J.; Siano, A. Creating a national identity through community relations: The context of a developing country. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Corporate and Marketing Communications. CMC2017—Challenges of Marketing Communications in a Globalized World, Zaragoza, Spain, 4–5 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, A.; Oprisan, O.; Condrea, E. Other economico-social factors of the saving process. HOLISTICA-J. Bus. Public Adm. 2017, 8, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Bank. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Shipalana, P. Digitising Financial Services: A Tool for Financial Inclusion in South Africa? SAIIA. Occas. Pap. 2019, 31, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, M.A.; Birkenmaier, J.; Bae, J. Financial exclusion in OECD countries: A scoping review*. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L.; Singer, D. The Opportunities of Digitizing Payments; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Triki, T.; Faye, I. Financial Inclusion in Africa; African Development Bank: Tunis, Tunisia, 2013; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Apiors, E.K.; Suzuki, A. Mobile money, individuals’ payments, remittances, and investments: Evidence from the Ashanti Region, Ghana. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyshon, A.; Thrift, N. The restructuring of the U.K. financial services industry in the 1990s: A reversal of fortune? J. Rural. Stud. 1993, 9, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.A. Supporting social enterprises to support vulnerable consumers: The example of community development finance institutions and financial exclusion. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tita, A.F.; Aziakpono, M.J. The effect of financial inclusion on welfare in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from disaggregated data. Econ. Res. S. Afr. Work. Pap. 2017, 679, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Soumaré, I.; Tchana, F.T.; Kengne, T.M. Analysis of the determinants of financial inclusion in Central and West Africa. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2016, 8, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelache, C.; Niță, D.O.G. Analiza statistică aincluziunii financiare. Rom. Stat. Rev. Suppl. 2019, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lorena, I.P.; Florin, R.; Iuliana, T.A. Needs of local sustainable development. Ann. Fac. Econ. 2011, 1, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, M.; Voica, M.C. Social Responsibility in the Financial and Banking Sector. Econ. Insights-Trends Chall. 2013, 2, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ene, C.; Panait, M. The financial education-Part of corporate social responsibility for employees and customers. Rev. Romana Econ. 2017, 44, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Brezoi, A.G. Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility in the Current Geopolitical Context. Econ. Insights-Trends Chall. 2018, 7, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tăbîrcă, A.I.; Ivan, O.R.; Radu, F.; Djaouahdou, R. Qualitative Research in WoS of the Link between Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Financial Performance. Valahian J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 10, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, M. Responsabilitatea socială a corporaţiilor şi instituţiilor şi dezvoltarea durabilă a României. Bucharest. Expert Publ. House 2013. Available online: https://www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro/temp/Articol_1014.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Iacovoiu, V.; Stancu, A. Competition and Consumer Protection in the Romanian Banking Sector. Amfiteatru Econ. 2017, 19, 381. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, D. Remittances: The new development mantra? Remit. Dev. Impact Future Prospect. 2005, 2, 331–360. [Google Scholar]

- FinScope, 2015, FinScope South Africa 2015. Available online: http://www.finmark.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Broch_FinScopeSA2015_Consumersurvey_FNL.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, G.; Ntayi, J.M.; Munene, J.C.; Nabeta, I.N. Financial inclusion in rural Uganda: Testing interaction effect of financial literacy and networks. J. Afr. Bus. 2016, 17, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Mayer, C. Mobile Banking and Financial Inclusion: The Regulatory Lessons; Frankfurt School of Finance and Management: Frankfurt, Germany, 2011; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, K. Mobile Money for Financial Inclusion. Inf. Commun. Dev. 2012, 61, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mago, S.; Chitokwindo, S. The Impact of Mobile Banking on Financial Inclusion in Zimbabwe: A Case for Masvingo Province. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 221. [Google Scholar]

- Mutsune, T. No Kenyan left behind: The model of Financial Inclusion through Mobile banking. Rev. Bus. Financ. Stud. 2015, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, G.; Munene, J.C. Analyzing the Relationship between Mobile Money Adoption and Usage and Financial Inclusion of MSMEs in Developing Countries: Mediating Role of Cultural Norms in Uganda. J. Afr. Bus. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S.A.; Odongo, T.M.; Were, M. Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization? Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, I.H.; Idi, A.; Ibrahim, Y. Innovation determinants of financial inclusion in top ten African countries: A system GMM approach. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2018, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafe, F. Ambiguity in international finance and the spread of financial norms: The localization of financial inclusion in Kenya and Nigeria. Rev. Int. Politi-Econ. 2020, 27, 500–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Oguntoye, A. The (non-)emergence of mobile money systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A comparative multilevel perspective of Kenya and Nigeria. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 131, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I. Regulatory frameworks and Implementation patterns for Mobile Money in Africa: The case of Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria. In Aalborg University Conference Paper; National Information Technology Agency: Accra, Ghana, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. Global Financial Development Report 2014: Financial Inclusion; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, W.; Fantom, N. World Development Indicators 2014; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 1–137. [Google Scholar]

- EFInA Access to Financial Services in Nigeria 2010–2018 Survey. Available online: https://www.efina.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/A2F-2018-Key-Findings-11_01_19.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Oyelami, L.O.; Saibu, O.M.; Adekunle, B.S. Determinants of financial inclusion in Sub-Sahara African countries. Covenant J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 104–116. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Nigeria/Nigerian Deposit Insurance Corporation (2020). Available online: https://ndic.gov.ng/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF). Available online: https://www.uncdf.org/financial-inclusion-and-the-sdgs (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alenoghena, R.O. Financial Inclusion and Per Capita Income in Africa: Bayesian VAR Estimates. Acta Univ. Danub. Acon. 2017, 13, 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, K.; Goodman, A.R.; Kenward, S. Lessons from the Chars Livelihoods Programme, Bangladesh (2004–2010). In Proceedings of the CPRC International Conference, Manchester, UK, 8–10 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anghelache, C.; Partachi, I.; Anghel, M.G. Remittances, a factor for poverty reduction. Rom. Stat. Rev. Suppl. 2017, 65, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hove, L.; Dubus, A. M-PESA and Financial Inclusion in Kenya: Of Paying Comes Saving? Sustainability 2019, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aga, G.A.; Peria, M.S.M. International Remittances and Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ajefu, J.B.; Ogebe, J.O. Migrant remittances and financial inclusion among households in Nigeria. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2019, 47, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, P.; Ruiz-Arranz, M. Remittances, financial development, and growth. J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 90, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, A.; Weill, L. The determinants of financial inclusion in Africa. Rev. Dev. Financ. 2016, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PWC. Is the rise of Pan-African Banking the Next Big Thing in Sub-Saharan Africa? 2017. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/economy/global-economy-watch/rise-of-pan-african-banking.html (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- World Bank, Global Findex Data. Available online: https://globalfindex.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Singh, A.B. Mobile Banking Based Money Order for India Post: Feasible Model and Assessing Demand Potential. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tiwari, R.; Buse, S.; Herstatt, C. Customer on the move: Strategic implications of mobile banking for banks and financial enterprises. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on E-Commerce Technology, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 June 2006; p. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Akturan, U.; Tezcan, N. Mobile banking adoption of the youth market. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Leiva, F.; Climent-Climent, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Determinants of intention to use the mobile banking apps: An extension of the classic TAM model. Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2017, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K. Integrating cognitive antecedents into TAM to explain mobile banking behavioral intention: A SEM-neural network modeling. Inf. Syst. Front. 2017, 21, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luarn, P.; Lin, H.-H. Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use mobile banking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2005, 21, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, W.; Charfeddine, L. Factors affecting the adoption of Internet banking in Tunisia: An integration theory of acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2012, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Lin, H.H.; Luarn, P. Predicting consumer intention to use mobile service. Inf. Syst. J. 2006, 16, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Q.; Ji, S.; Qu, G. Mobile commerce user acceptance study in China: A revised UTAUT model. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2008, 13, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyasi, F.I.; Otubu, P.A. Mobile phone technology in banking system: Its economic effect. Res. J. Inf. Technol. 2009, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, A.A.; Ayo, C.K. An Empirical Investigation of the Level of Users’ Acceptance of E-Banking in Nigeria. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2010, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu, A.A.; Younus, S.; Tasmin, R.B.H.J. An exploratory study on adoption of electronic banking: Underlying consumer behaviour and critical success factors: Case of Nigeria. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, O.J.; Ajiboye, F.; Dunsin, A.T. An Investigative Study on Factors Influencing the Customer Satisfaction with E-Banking in Nigeria. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Adewoye, J.O. Impact of mobile banking on service delivery in the Nigerian commercial banks. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Agwu, P.E.; Carter, A.L. Mobile phone banking in Nigeria: Benefits, problems and prospects. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2014, 3, 50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhini, A.; Mgbemena, C.; Trab, M.S.A.; Masa’Deh, R. User adoption of online banking in Nigeria: A qualitative study. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2015, 20, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Agu, B.O.; Simon, N.P.N.; Onwuka, I.O. Mobile banking–adoption and challenges in Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2016, 4, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.U.; Ejike, A.C. An assessment of the impact of mobile banking on traditional banking in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2017, 11, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagudu, H.D.; Khan, S.J.M.; Roslan, A.H. The Effect of Mobile Banking on the Performance of Commercial Banks in Nigeria. Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2017, 4, 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bille, F.S.; Buri, S.; Crenn, T.A.; Denyes, L.S.; Hassam, C.V.T.; Heitmann, S.; Martinez, M. Digital Access: The Future of Financial Inclusion in Africa; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Using qualitative research synthesis to build an actionable knowledge base. Manag. Decis. 2006, 44, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. 10 year retrospect on stage models of e-Government: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimi, L.; Uzodinma, I. Trends in Financing Programmes for the Development of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Nigeria: A Qualitative Meta-synthesis. In Contemporary Developments in Entrepreneurial Finance. FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Moritz, A., Block, J., Golla, S., Werner, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson, K.W.; Dixon, A. Qualitative meta-synthesis: A guide for the novice. Nurse Res. 2008, 15, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; Downe, S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Methodol. Issues Nurs. Res. 2005, 50, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Nigeria. Annual Statistical Bulletin. 2020. Available online: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/documents/Statbulletin.asp (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, S.K.; Darmody, A. Co-creating second life: Market—Consumer cooperation in contemporary economy. J. Macromarket. 2008, 28, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinoda, T.; Kwenda, F.; McMillan, D. Do mobile phones, economic growth, bank competition and stability matter for financial inclusion in Africa? Cogent Econ. Financ. 2019, 7, 1622180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinoda, T.; Kwenda, F. Financial Inclusion Condition of African Countries. Acta Univ. Danub. Acon. 2019, 15, 242–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Naceur, S.; Barajas, A.; Massara, A. Can Islamic Banking Increase Financial Inclusion? Int. Monet. Fund. 2015, 213–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Area | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Adult using Formal Payments System | 22 | 20 | 24 | 38 | 40 |

| % of Adult with Savings Accounts | 24 | 25 | 32 | 36 | 24 |

| % of Adult enjoying Credits | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| % of Adult with Insurance Policies | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| % of Adult with Pension Schemes | 5 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| % of Adult Financial Exclusion | 46.3 | 39.7 | 39.5 | 41.6 | 36.8 |

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Banks | 24 | 24 | 21 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 29 |

| Branches Abroad | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Abia | 146 | 125 | 138 | 147 | 144 | 135 | 142 | 137 | 135 | 135 |

| Abuja (FCT) | 398 | 359 | 379 | 397 | 380 | 369 | 421 | 437 | 382 | 390 |

| Adamawa | 67 | 79 | 63 | 61 | 47 | 47 | 57 | 64 | 66 | 60 |

| Akwa-Ibom | 99 | 92 | 100 | 94 | 92 | 103 | 106 | 114 | 88 | 102 |

| Anambra | 237 | 222 | 228 | 224 | 219 | 218 | 219 | 214 | 209 | 227 |

| Bauchi | 53 | 50 | 46 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 50 | 47 | 55 | 47 |

| Bayelsa | 37 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 35 | 35 |

| Benue | 75 | 57 | 73 | 76 | 67 | 63 | 69 | 71 | 78 | 65 |

| Borno | 79 | 68 | 71 | 69 | 83 | 72 | 60 | 61 | 58 | 56 |

| Cross-River | 79 | 76 | 76 | 80 | 79 | 74 | 78 | 79 | 72 | 75 |

| Delta | 198 | 177 | 194 | 198 | 178 | 180 | 200 | 205 | 183 | 183 |

| Ebonyi | 35 | 45 | 33 | 33 | 59 | 61 | 37 | 36 | 59 | 42 |

| Edo | 183 | 162 | 188 | 192 | 144 | 165 | 178 | 188 | 159 | 177 |

| Ekiti | 80 | 60 | 64 | 76 | 91 | 87 | 86 | 92 | 76 | 77 |

| Enugu | 141 | 116 | 142 | 147 | 158 | 151 | 159 | 162 | 127 | 148 |

| Gombe | 40 | 36 | 36 | 37 | 43 | 41 | 36 | 37 | 65 | 34 |

| Imo | 104 | 97 | 100 | 102 | 110 | 105 | 98 | 100 | 99 | 94 |

| Jigawa | 39 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 63 | 66 | 38 | 36 | 43 | 34 |

| Kaduna | 183 | 170 | 169 | 171 | 154 | 164 | 168 | 173 | 169 | 157 |

| Kano | 193 | 186 | 183 | 183 | 174 | 170 | 178 | 179 | 195 | 161 |

| Katsina | 62 | 55 | 58 | 59 | 73 | 78 | 56 | 55 | 52 | 47 |

| Kebbi | 40 | 40 | 37 | 38 | 95 | 37 | 37 | 35 | 49 | 61 |

| Kogi | 80 | 77 | 82 | 84 | 88 | 80 | 79 | 82 | 70 | 71 |

| Kwara | 79 | 139 | 75 | 79 | 104 | 101 | 78 | 84 | 100 | 85 |

| Lagos | 1766 | 1453 | 1692 | 1678 | 1443 | 1486 | 1645 | 1686 | 1478 | 1624 |

| Nasarawa | 58 | 51 | 49 | 48 | 68 | 69 | 49 | 49 | 67 | 52 |

| Niger | 80 | 76 | 79 | 82 | 67 | 65 | 78 | 86 | 64 | 71 |

| Ogun | 175 | 402 | 161 | 154 | 137 | 142 | 154 | 172 | 153 | 169 |

| Ondo | 121 | 109 | 110 | 119 | 106 | 101 | 113 | 120 | 120 | 112 |

| Osun | 105 | 118 | 101 | 104 | 101 | 99 | 106 | 108 | 86 | 99 |

| Oyo | 236 | 203 | 223 | 237 | 347 | 343 | 222 | 237 | 195 | 223 |

| Plateau | 79 | 72 | 77 | 75 | 75 | 71 | 70 | 67 | 75 | 83 |

| Rivers | 302 | 246 | 310 | 311 | 292 | 275 | 312 | 319 | 275 | 301 |

| Sokoto | 53 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 43 | 45 | 53 | 52 | 60 | 47 |

| Taraba | 37 | 41 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 34 | 27 | 39 | 30 |

| Yobe | 35 | 35 | 33 | 35 | 38 | 41 | 34 | 31 | 27 | 29 |

| Zamfara | 35 | 33 | 34 | 40 | 39 | 38 | 30 | 31 | 38 | 34 |

| TOTAL | 5809 | 5454 | 5564 | 5639 | 5526 | 5470 | 5570 | 5714 | 5301 | 5437 |

| SN | Policies on Financial Inclusion | Governance Level | Target Audience |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Economy Reconstruction Fund (NERFUND) | National | Individuals and Businesses across Nigeria |

| 2 | People’s Bank of Nigeria | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses across Nigeria |

| 3 | Community Banking Models | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses |

| 4 | Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses |

| 5 | Bank of Industry (BOI) | National | Corporate entities—SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) across Nigeria |

| 6 | Small and Medium Enterprises Equity Investment Scheme (SMEEIS) | National | Corporate entities—SMEs across Nigeria |

| 7 | National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP) | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses |

| 8 | Youth Enterprise with Innovation in Nigeria (You Win) Programme | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses |

| 9 | Subsidy Reinvestment & Empowerment Programme (SURE-P) | National | Individuals, petty traders, artisans and small businesses |

| 10 | Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) | International | National institutions, People and businesses |

| 11 | Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | International | National institutions, People and businesses |

| SN | Nature of Barrier | Barrier Classification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Government’s inability to properly nurture its financial inclusion interventions and programmes | Institutional factor |

| 2 | Dysfunctional structures and endemic poor programme implementation | Institutional factor |

| 3 | Structure of the economy (Agriculture-based economy) | Institutional factor |

| 4 | Location of the majority of the population | Environmental factor |

| 5 | Bureaucracy of financial operations | Environmental factor |

| 6 | High costs of banking products and services | Environmental factor |

| 7 | Distance of banks to the population. | Environmental factor |

| 8 | Number of money deposit bank branches | Environmental factor |

| SN | Value in Use (VIU)Sub-Constructs | Determinants/Drivers of Mobile Banking | Main Specific Factor Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Experience | Utility expectancy | Prompt, transaction notification, Trust and privacy, Satisfaction using mobile banking |

| 2 | Personalization | Effort expectancy | Convenience and cost, Ease of management, personal banking transactions |

| 3 | Relationship | Social influence expectancy | Influence of advert, opinions of friends and relatives, behavioural influence of people on mobile banking, institutional policy on cashless policy, other pressures |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siano, A.; Raimi, L.; Palazzo, M.; Panait, M.C. Mobile Banking: An Innovative Solution for Increasing Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310130

Siano A, Raimi L, Palazzo M, Panait MC. Mobile Banking: An Innovative Solution for Increasing Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310130

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiano, Alfonso, Lukman Raimi, Maria Palazzo, and Mirela Clementina Panait. 2020. "Mobile Banking: An Innovative Solution for Increasing Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310130

APA StyleSiano, A., Raimi, L., Palazzo, M., & Panait, M. C. (2020). Mobile Banking: An Innovative Solution for Increasing Financial Inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Sustainability, 12(23), 10130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310130