1. Introduction

In recent years, the number of organic vineyards has increased significantly across the globe [

1,

2]. According to the International Wines and Spirits Record (IWSR) [

3], Germany has one of the world´s largest markets for organic wine, leading some to assume that there is an active demand for the product in the country. Regardless, several studies have revealed that this growing supply is not indicative of a consistently increasing demand. According to studies by Remaud et al. [

4], Hoffmann and Szolnoki [

5] and Szolnoki and Hauck [

6], there is a low awareness of and correspondingly low demand for organic wine, which is not the case for organic foods.

As several studies have reported, although the motives for switching to organic wine production vary, it is a winemaker’s personal convictions that primarily contribute to this decision rather than economic or market expectations [

7,

8,

9]. Indeed, Hauck and Szolnoki’s [

9] research indicated that one of the main reasons that conventional wine producers do not switch to organic production is the lack of demand.

Following from a study of the German organic wine market which showed a discrepancy between the total volume of organic wine produced in Germany (1.16 million hl) and the country’s active demand for the product (0.54 million hl), it is likely that half of German wine consumers purchase organic wine without being aware of its organic certification [

6]. The present study investigates the lack of active demand for organic wine, focusing on consumers’ awareness of organic certification and their knowledge and attitudes about organic wine.

Yiridoe et al. [

10] determined that consumers´ organic food purchases are driven by awareness about food safety, human health, animal welfare and environmental protections and reparations. In contrast, Szolnoki and Hauck [

6] noted that whether a product is organic is irrelevant to individuals who purchase wine. In addition, Corsi and Strøm [

11] and Schmit et al. [

12] observed that a product’s designation as organic is typically not pertinent to those who buy wine. Nonetheless, the lack of awareness about the organic attribute may be explained by the complex nature of wine selection [

13]. Some studies analyzing wine purchasing decisions have found that origin is the most essential criterion for choosing wine [

14,

15,

16], followed by price [

17], packaging and labelling [

18], variety [

19], brand [

20] and awards [

21]. These are the most relevant factors in consumers´ decisions to purchase wine. Other studies have reported that wine consumers find the method of production less important than the origin of the wine [

22,

23,

24]. Although approximately one-third of wine consumers are interested in environmentally friendly or environmentally sustainable wines [

25,

26], Delmas and Grant’s [

27] study indicated that altruistic buying motives for organic food, such as environmental protection or animal welfare, are usually not associated with the production of organic wine. In addition, Delmas [

28] and Zucca et al. [

29] noted that consumers have low levels of knowledge about organic wine production. Consumers also frequently perceive wine as a natural product [

30,

31]. For these reasons, consumers do not make the same positive associations with organic wine as they do with organic food and thus purchase organic wine more rarely [

4,

32].

The purchasing motives and barriers for organic food and wine are similar. For both organic food and wine, the numerous purchasing barriers include higher prices [

9,

22,

24,

30,

33], inferior taste and lower quality [

24,

34,

35], little knowledge about organic attributes [

6,

36], and a lack of familiarity with and trust in organic products [

37,

38,

39]. Lower income also negatively affects organic food purchasing [

40,

41,

42]. Szolnoki and Hauck [

6] identified a similar correlation in organic wine.

In spite of the negative factors that hinder the purchase of organic food or wine, there are also positive features that increase their demand. Marian et al. [

43] found that the premium pricing of organic foods can lead consumers to perceive them as high-quality products. Several authors have also shown that the motives for purchasing organic wine are primarily altruistic. Self-serving motives, such as positive health effects [

24,

32,

44,

45,

46,

47] and better taste [

48,

49], are relevant factors for buying organic wine. By performing sensory evaluations, Pagliarini et al. [

50] and Wiedmann et al. [

49] determined that a product’s organic attributes positively affect some consumers’ perceptions of wine taste and quality. Consumers who perceive organic production as environmentally friendly also have a higher likelihood of purchasing organic wine [

44,

45,

46,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Moreover, consumers are willing to pay more for organic wine due to the environmental benefits of its production [

45,

46,

51,

56]. Despite the findings from the abovementioned studies, some studies have found no correlation between consumers´ attitudes and their purchasing intentions for organic wines [

24,

48,

57].

Various international studies have revealed that some wine consumers prefer sustainable wines [

55,

57,

58,

59], choose organic over conventional wines [

22,

24,

60] and are more willing to pay a premium for organic wines [

49,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]. Consumers with a strong environmental orientation are especially willing to buy organic wines [

63]. In addition, the results of Schäufele and Hamm’s [

55] attitude-behaviour analysis of household panel data revealed that consumers´ attitudes match their purchasing behaviours in five out of six consumer clusters. Consumers who spend the most on organic wine show particularly strong pro-environmental attitudes and a preference for sustainable products. Furthermore, environmental and health benefits are more pertinent to consumers who buy wine for their own consumption and who purchase wine frequently and are highly involved in the product [

64,

65]. Zander and Janssen [

63] reported that consumers who regularly buy wine are more willing to purchase organic wine. This finding was confirmed by Szolnoki and Hauck’s [

6] study, which revealed that consumers purchase more organic wine when their interest in and knowledge of wine is greater.

According to several authors, the most frequent demographic characteristics of sustainable and organic wine consumers are as follows: most are females [

6,

24,

25,

57,

58,

64,

65] with higher incomes [

6,

65,

66,

67], who live in urban areas [

14,

24,

68]. Szolnoki and Hauck [

6] found that the rate of upper-class wine consumers, or those with higher incomes and educational and occupational levels, is 46%. Szolnoki and Hauck [

6] only noted a marginal difference in the purchasing share of non-organic wines between consumers who were 52 years or older and other age groups. Mann et al. [

24] and D´Amico et al. [

46] identified no significant differences between age in the consumption of organic wine. By contrast, Thach and Olsen [

69] found that because young adults are more informed about environmental and social issues, they are more likely to appreciate organic wine [

22,

70]. Tasting organic wine can positively impact consumers’ perceptions of the product’s quality when they have little knowledge about it [

27]. For consumers with a higher income, attitude towards organic food plays a critical role [

70]. In a choice experiment with German consumers, although Risius et al. [

71] determined that an organic label can have a slightly positive influence on preferred wine, this influence was marginal when compared to other attributes, such as sweetness, producer, grape variety and origin. Delmas and Grant [

27] found that organic wine labels can only be successful if consumers are aware of their certification. Hauck and Szolnoki [

72] noted that while only 44.7% of German consumers know the EU organic label, other German organic certifications, such as Biokreis, Bioland, ECOVIN, Naturland and Demeter, are even less well known. Consumers´ valuations of organic wine production are influenced by the fair [

73] and sustainable practices of organic wine producers [

44].

As the present literature review has revealed, many papers have investigated the purchasing motives and barriers of organic food and wine. Nonetheless, there is a lack of detailed studies on wine consumers´ knowledge of and attitudes about these products’ organic attributes that integrate focus group discussions, wine choice observations and acceptance tests. Therefore, the current study aims to answer the following four research questions:

Research Question 1—Are wine consumers aware of an organic certification during their wine purchase decision?

Research Question 2—What do consumers know about organic wine production?

Research Question 3—Do organic attributes positively or negatively influence purchasing decisions?

Research Question 4—How can the awareness, consideration and willingness to pay for organic wine be improved?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focus Group Discussions

In order to analyze wine consumers’ reactions during the wine purchasing process and their knowledge and attitudes about organic wine, this study adopted a qualitative research approach that incorporated focus group discussions, wine choice observations and acceptance tests. The focus groups facilitated discussions between the participants so that revealing insights into consumers´ perceptions and attitudes in the wine purchasing process could be collected. Since most studies have applied a quantitative approach to examine wine consumers’ attitudes and behaviours, we used a qualitative method to gather more detailed information and to form a better understanding of the organic wine market.

A guideline based on existing literature was developed to prepare for the focus group discussions. To ensure consistency, the guideline was drawn up by the same person who moderated the focus groups and conducted the analysis. A pre-test was conducted in Geisenheim, Germany to verify the guidelines and framing of the group discussions.

To guarantee unbiased reactions, the participants were only informed about the study’s topic during the focus group. This made it possible to observe their reactions to both the organic attributes and organic wine as a whole. In addition, the participants’ wine choices were observed to obtain valid assessments of their consumer behaviours and their individual appraisals so that the first research question could be addressed. Finally, in order to answer Research Question 4, acceptance tests were conducted to examine the factors influencing consumers’ buying intentions and willingness to pay a premium for organic wine.

In June 2019, 12 focus group discussions were held in different German cities. These consisted of four discussions in each city: Berlin, Frankfurt and Munich. The cities were chosen to represent a geographical spread covering central (Frankfurt), northeast (Berlin) and southeast (Munich) Germany. These cities were either surrounded by wine-growing regions (Frankfurt) or located far from wine-growing regions (Berlin and Munich). In addition, the chosen cities varied in size: 3.8 million inhabitants in Berlin, 1.5 million inhabitants in Munich and 750,000 inhabitants in Frankfurt.

Each focus group discussion had 6 to 8 participants and lasted for approximately 90 min. The sample was recruited using a screening quota for gender, age and wine consumption (at least once a month) that was selected by a panel from an external market research institute. The group sizes of six to eight participants were chosen to facilitate interaction and discussion in the groups and to ensure ample time for all participants to state their opinions [

74]. The focus groups were divided according to age and gender. At each site, four discussions were conducted with the following participant groups: (1) females, 25 to 40 years old; (2) females, 41 to 65 years old; (3) males, 25 to 40 years old; and (4) males, 41 to 65 years old.

A central professional setting was chosen to increase attendance and reduce distractions. To decrease bias in the participants’ attitudes prior to data collection, the participants were informed in advance that they were taking part in a focus group discussion about wine but not that it focused on organic wine. One trained moderator per site was responsible for ensuring that every relevant aspect of the study was covered during the focus group discussions [

75,

76].

First, a quantitative questionnaire was administered to collect sociodemographic data and wine-related information from the participants. Then, the focus group was initiated by giving a brief introduction so that participants could familiarise themselves with each other and the setting. As a warm-up task and to provide a general overview of the selected participants, the participants were asked to describe their frequency of wine consumption, their preferred shopping and consumption locations and their wine preferences.

2.2. Wine Choice Observation and Acceptance Tests

The participants were asked to choose between six different wine bottles presented on a table. This process aimed to simulate a retail setting with a reduced number of wines, enabling us to identify any behaviour gaps and confront the participants with them. All six bottles were Rieslings, one of the most popular grape varieties in Germany and across various regions known for their production of wine. Three regions with a share of Riesling were selected: Rheingau, Rhine-Hesse and Palatinate. One conventional producer and one organic certified producer were chosen per region (

Table 1). To prevent price level and taste from influencing the participants’ responses, each bottle’s price was set to 6.99 euros, all wines were dry and of the same vintage and each contained alcohol by volume of 12% to 12.5%. In addition, different organic labels were chosen, such as the German organic label, the EU organic label, the Bioland organic label and the Respekt Biodyn organic label. As illustrated in

Table 1, the EU organic label was used in combination with another organic certification. After the participants made their individual choices, they were asked about their decision strategies and to describe the characteristics of their purchasing decisions. Once the choice test had been discussed, the participants were informed about the topic of the focus group (organic wine). In the next step, the participants were asked about their general attitudes towards organic products and their purchasing and consumption behaviours with organic products. The participants were also asked to define the product categories where organic certification is relevant and why. If the participants did not mention organic wine, they were asked if they knew about organic wine and what they expected from or knew about organic wine certifications. Furthermore, the participants discussed their impressions and thoughts in the group. To stimulate the discussion, the participants were asked to describe how wine is typically produced. They also discussed whether they perceived wine as a natural product.

Finally, an acceptance test was conducted. First, the participants were confronted with facts about EU organic wine regulations and the main differences between conventional and organic wines according to these regulations. This information was presented in written form. Second, they received the same facts in the form of pictures of organic and conventional vineyards. To trigger strong reactions, pictures were selected that showed the best- and worst-practice samples of organic and conventional wine production. The pictures of conventional wine production showed wine rule-consistent use of pesticides in the vineyards, with barren ground and monoculture. The pictures of organic wine production showed mechanical plant protection as well as the use of blossom mixtures. After each case, participants were required to fill in a sheet specifying whether the given information influenced their purchasing intentions and willingness to pay a surplus for organic wine. Afterwards, the information was discussed. The discussion was closed with a reflection and suggestions on how the focus on organic wine could be improved.

2.3. Participants

To join the focus group discussions, participants were required to consume wine at least once a month. Wine experts working in the wine or beverage industry were excluded. The study’s aim was to recruit wine consumers with a wide range of sociodemographic characteristics (

Table 2). When compared to general wine consumers in Germany [

77], a higher share of participants was in the age groups of 30–39, and 40–49 and a lower share was in the 60+ age group. Wine consumption frequency, wine knowledge and wine involvement were also higher. Nonetheless, the difference in the number of purchasing channels was marginal between the study’s participants and general wine consumers in Germany. Therefore, although this sample is not representative of the total population in Germany, it provides insight into consumers´ perceptions at a qualitative level.

2.4. Analysis

In order to collect base material, all focus group discussions were filmed, recorded and transcribed. Based on the literature review, theoretical assumptions were made prior to the content analysis with open, axial and selective coding [

78]. The transcripts were then summarised using content analysis with inductively created categories and grounded theory [

79] using MAXQDA (Verbi, Germany).

In addition, SPSS 27.0 (IBM, USA) was used to analyze the wine choice observations and acceptance tests and to perform a descriptive analysis of the questionnaires that gathered the participants’ sociodemographic and wine-related characteristics.

3. Results

3.1. Awareness of Organic Wine

After the simulated purchase decision process, which required each participant to choose one of the six bottles, only three participants (out of 91) justified their choice by referring to the organic label. Although the participants were allowed to look at the back label, most of them (81 out of 91) did not recognize the organic certification. When asked about their purchasing decision, one participant stated as follows: “For me, taste and price are most important. So, I checked the price, read the sensory description and made my decision.” For other participants, the wine selection did not include their favourite wines in terms of origin, variety, style or taste. A female participant was supported by the rest of her focus group when she said, “I hate purchasing a bottle of wine. You have to consider so many factors. I am always afraid of making the wrong choice.” Other participants agreed, saying, “there are too many different wines and they are confusing”. This highlights the challenge of purchasing wine: several factors must be considered before consumers can make their decisions. The visibility of organic certification was also discussed. “It is not in my focus, because it is mostly not visible at first sight,” a female participant said when referring to bottles where the organic label was located on the back label. Some participants observed that organic wines are more eye-catching at discount retail stores because they feature organic banderoles and labelling on the front of the bottle.

One younger male participant, who introduced himself as an “organic hardliner” before learning that the study’s focus was on organic wines, chose one of the conventional wines during the purchasing experiment. When confronted with this result, he expressed surprise and confirmed that although the organic attribute was important to him, he focused on attributes other than a wine’s organic qualities when making purchasing decisions. He expressed that he usually only bought wine at organic or sustainable supermarkets where he could trust the entire range of products. Another male participant confirmed this argument by saying, “I trust my wine distributor and follow his recommendations.”

When reflecting on previous purchasing situations, most participants remarked that they had noticed organic certification on wine labels in the past but said that it did not awaken their interest. As mentioned previously, price, origin, variety and taste had a higher impact on their purchasing decisions. As one older male participant put it, “Why should I care if it is organic? It is still an alcoholic beverage.” A similar sentiment was shared in another focus group: “Wine is not healthy, that´s why I do not care whether it’s organic.” Around two-thirds of the participants (62 out of 91) were aware of the organic certification on animal products, fruits and vegetables and primarily associated the certification with animal welfare and healthier food with less chemical residue. However, in response to the first research question—’Do wine consumers notice organic attributes?’—the wine choice observations and the ensuing discussion, most participants were unaware of the organic certifications on wines.

3.2. Knowledge about Wine Production

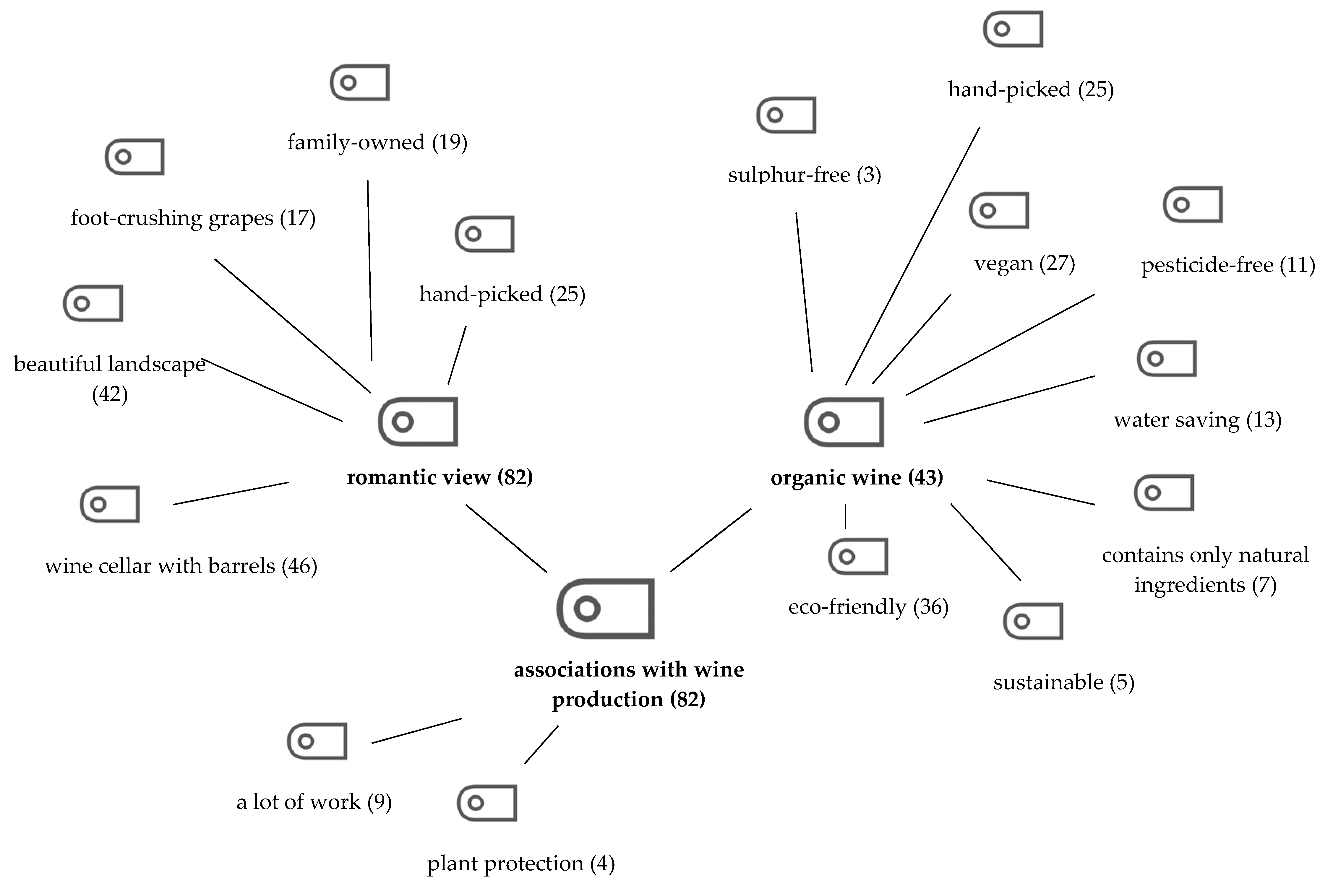

When we informed the participants that the discussion’s focus was organic wine, they made several statements and asked a number of questions. First, the participants were confused—and asked, “Isn´t wine a natural product in general?”, revealing a lack of knowledge about the methods that are common to wine production. Before beginning the focus group discussion, the participants were instructed to answer a questionnaire so that data about demographics, general wine consumption and knowledge could be collected. Only 4 participants assessed their knowledge of wine to be low, 42 considered their knowledge to be average, and 45 believed their knowledge to be high. When asked to describe their associations with wine production in Germany, the participants mostly named stereotypical images, such as ‘a romantic wine cellar with barrels’ (46 out of 91), ‘a beautiful landscape’ (42 out of 91), ‘grapes with feet’ (17 out of 91), ‘hand-picked’ (25 out of 91) and ‘family-owned’ (19 out of 91). In contrast to the participants’ claims at the beginning of the focus group discussions, the discussions revealed that most consumers have poor knowledge about wine production (

Figure 1).

The participants’ knowledge about organic wine production was even lower. In response to Research Question 2 ‘What do consumers know about organic wine production?’ participants who were aware of organic labels for both food and wine described organic wine as “pesticide-free”, “eco-friendly”, “sustainable” or “sulphur-free”. Other participants speculated that organic wine contains “only natural ingredients”, “saves water” or is “vegan”. A female consumer of organic food and wine pointed out the differences between organic certifications in “average organic labels and better organic labels like Bioland, Naturland or Demeter.” The mentioned private organic associations adhere to the EU organic regulations with specific and stricter rules that govern production. Uncertainties about the definition of organic wine confused some participants and led to rejection in some cases: “I don´t know what to drink or eat. You always have to be aware of certifications. That is not enjoyment for me, wine should be enjoyment.” This statement and others indicated that for some wine consumers who have no interest in being informed, enjoyment is more important than knowledge. Such findings also indicate that consumers struggle with the complexity of sustainable or organic production conditions. One participant expressed that they were generally overwhelmed by wine purchasing decisions and their lack of knowledge about wine: “The variety of wines is too much. I cannot interpret the information on the label.” The focus groups also focused on the definition of the word ‘organic’. Some statements, such as “Organic needs to be sustainable” and “Sustainable products are always organic”, indicated that most participants believed that a product’s sustainability and organic attributes are mutually exclusive.

When asked about the sources of their knowledge, most participants identified the ‘media’ and the ways in which wine production is portrayed in marketing. Only a few participants mentioned wine producers’ workload, especially in the vineyard, and the level of plant protection that is necessary to grow vines. These participants noted that they had visited wineries or had close contact with wine producers.

The discussion showed that while most wine consumers have a romantic view of wine production, the majority of the participants were not interested in the veracity of this image. Although visiting a winery can improve knowledge about wine production, general communication about wine leads consumers to assume that wine is handcrafted and individually produced.

3.3. Attitude towards Organic Production

In response to Research Question 3, ‘Do organic attributes positively or negatively influence purchase decisions?’, participants´ attitudes varied considerably (see

Table 3). A large number (72 of 91) of participants stated that they did not trust organic certification and criticized the lack of transparency: “There are so many certifications and then you hear about their low standard. It is just moneymaking.” Due to a lack of knowledge about the certifications and their control mechanisms, many participants perceived organic wines to be more expensive. As a result, they believed that organic certification functioned as an avenue for producers to earn more money. Consumers are not aware of the higher workload or costs involved in producing organic wine. Depending on the location of the focus groups, the participants’ willingness to pay a premium for organic wines varied significantly. As one female participant in Berlin remarked, “I would love to buy organic. I care about the environment and about my own health. But the rent in the city is high. I need to calculate carefully every month and I only buy organic if it is not more expensive than conventional food.” This sentiment was confirmed by several other participants. Participants’ sensitivity to the price of organic products was much higher than it was in Munich, especially if they lived in Berlin or Frankfurt. It also showed that while consumers are aware of the benefits of organic products, buying organic does not take priority if their income is low.

According to one female participant, “buying local products is more sustainable than buying organic products.” Nearly half of the participants (42 out of 91) defined regionality as more important than organic production. Moreover, foreign organic products were viewed critically: “a pineapple from Brazil cannot be sustainable”; “I am sure that they have lower control mechanisms abroad compared to Germany. I don´t trust this system.” Participants were also sceptical of the large range of organic products in discount stores: “Discounter shops do not stand for sustainability”; “Where does the mass of organic products come from?” When asked to clarify these doubts with sources, they reported that ‘media headlines’ played a critical role. As one participant surmised, “I once saw a documentary about organic standards and was shocked. I expected the regulations to be stricter.” Another participant remarked, “I go for the visual appearance and the price when buying fruit or vegetables. If conventional looks better, I choose conventional. If organic looks better, I choose organic.” He described himself as “neutral” towards organic, indicating that he used additional purchasing criteria.

A contrary position was represented by a few male participants (9 out of 91). At the beginning of the focus group discussions, when participants were asked to describe their wine consumption and purchasing behaviours, most of these participants characterized themselves as ecologically interested individuals who are regular purchasers at organic stores. “I started to consume organic products to support animal welfare, but I also tolerate organic food much better and I feel healthier,” one male participant argued. For these individuals, organic attributes are representative of healthier products, higher quality, fewer artificial ingredients and, most importantly, animal welfare. For some of the focus groups’ sceptics of organic labelling, animal welfare functioned as a valid argument for organic certification. In addition, a few participants agreed that organic products were healthier and of higher quality.

Participants who had already purchased organic wine to try it had different experiences. Some of them had been disappointed by the taste or by the fact that the quality was not higher than that of conventional wine. Most had only tried one organic wine, and, if they found the taste unacceptable, dismissed the organic attribute from their future purchasing decisions. Participants who had positive experiences and enjoyed the taste continued to buy organic wine but not exclusively.

In sum, the participants can be clustered according to four different attitudes/behaviours: 1) wine consumers who typically buy organic products and organic wines (9 out of 91); 2) wine consumers who focus only on organic animal products, not on organic wine (16 out of 91); 3) wine consumers who base their purchasing decisions on other criteria, such as a product’s price or visual appearance (57 out of 91); and 4) wine consumers who distrust organic products and avoid buying them since they associate organic products with moneymaking and consumer deception (9 out of 91).

3.4. Possibilities for Improving the Awareness and Image of Organic Wine

When making their purchasing decisions in the simulation, most (81 out of 91) participants did not see the organic labels. As one female participant stated, “Now, I see the organic label. But during the experiment, I did not notice it.” This sentiment was broadly shared within the focus groups. As noted in

Section 3.1, the visibility of organic certification was an issue for some participants since it was ‘not visible at first sight’. In answer to part of Research Question 4, the participants suggested that a banderole could be used with the organic designation and organic labelling on the front label to improve awareness.

As stated in

Section 3.2, there is poor knowledge about both conventional and organic wine production, which causes consumers to distrust organic certifications and negative influences to purchase organic wines. This perception applies to all organic products, not only organic wines. At the same time, wine is perceived to be a ‘natural product’, suggesting that consumers have little need to buy organic wine. This perception strongly influences consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for organic wine. As long as conventional and organic wines are priced the same, buyers will consider buying organic. Most participants noted that they are unwilling to pay more for organic wines. As one male participant stated, “If I like the taste, I pay more. But not just for organic.”

During the acceptance test, an overview of organic certifications and the value of organic wine influenced the participants’ knowledge about the product. One participant asked, “Have I got this right? Buying organic wine is mainly to protect the environment? This is new to me. I thought it is just like meat, healthier or higher quality.” After presenting the facts (

Table 4), more than one-third of the participants (34%) said they would consider buying organic wine or more organic wine, 12% were unsure and 46% remained unwilling to buy organic wine or more organic wine. Regarding price, 50% stated they would pay more for organic wine, 14% said they might pay more for organic wine and 36% said they would not pay more for organic wine.

In a subsequent step, facts about organic wine production were presented with pictures of best-practice organic production and worst-practice conventional vineyard management in order to intentionally provoke a discussion about the participants’ perceptions and observe their reactions to the images. Some pictures showed a wine rule-consistent, intense use of herbicides by conventional wine producers, which led to strong reactions. Some participants reacted to these pictures by stating, “How can this still be allowed?”; “No wonder bees are in danger of extinction!”; and “I´ll stop drinking wine!” In addition, the willingness to pay a premium increased and buying intention nearly doubled after this acceptance test (

Table 4). Furthermore, the pictures of worst-practice conventional production increased positive awareness about best-practice organic vineyards: “I thought that every vineyard looks like the organic one.”

The results of the acceptance test were significantly different when splitting the focus groups by gender and age. The younger focus groups (25 to 40 years old) generally reacted positively to the information and showed a high degree of willingness to consider purchasing organic wine in the future. The female focus groups in each city (41- to 65-years old) expressed the strongest positive perceptions in response to the acceptance tests. Therefore, in response to Research Question 4, the consideration and willingness to pay a premium for organic wine can be improved by providing information and pictures to certain targeted groups.

Around 80% of each focus group were willing to buy more organic wine or pay more for it. As one female participant posited, “Now, I will be sure to buy only organic wine.” In contrast, the male focus groups (41 to 65 years old) presented opposite reactions. Only one-third of these groups said they would consider organic wines during their future wine purchasing decisions. For most of the male participants, the information provided about organic wines did not change their general doubts or distrust of organic products. As one participant remarked, “I am growing old and am healthy without consuming organic products. Why start now?’ Another participant expressed their scepticism about the acceptance test: “I stick to it. It is just marketing.” Overall, most of the participants intended to increase their organic wine consumption after they were presented with information from the acceptance tests. Because females and participants from younger age groups showed a more positive reaction to information about organic wines than older male consumers, marketers should specifically address targeted groups. In addition, since 63% of the participants claimed to buy wine from discount retail stores and supermarkets, these shopping locations are the most suitable candidates for areas where visibility and awareness about organic wine can be improved.

4. Discussion

The results of the wine choice observations (Research Question 1) revealed that most participants were unaware of the organic attribute when making wine purchasing decisions. These results confirm findings by Corsi and Strøm [

11], Schmit et al. [

12] and Szolnoki and Hauck [

6], who showed that the organic designation is typically irrelevant when purchasing wine. As the focus groups confirmed, origin [

14,

15,

16], price [

17], packaging and labelling [

18] and variety [

19] are the most important criteria for selecting wine. Furthermore, the participants indicated that they struggled to cope with the wide range of wines offered at retail outlets. As Delmas and Grant [

27] observed, organic labels can only influence purchasing decision if consumers are aware of their certifications. This suggests that consumers must have knowledge about organic wine and that organic labels must be visible at first sight. In contrast, the focus group discussions revealed that organic certification is typically not visible since the certifications are generally only located on the back labels.

In addition, the participants showed low knowledge of wine and organic wine production (Research Question 2). Although Delmas [

28] and Zucca et al. [

29] examined knowledge about organic wine production, the focus group discussions indicated that consumers’ knowledge about wine production is generally poor. Thus, because consumers usually perceive wine as a natural product [

4,

30,

45], few consider the organic attribute to be a necessary standard. Consumers hold a romantic view of wine production and do not understand the effort required to produce wine and, especially, organic wine. A more realistic view and appreciation of the workload could be increased through clarification of the processes and winery visits.

The barriers and motives for buying organic wine are primarily influenced by consumers’ personal attitudes towards organic production (Research Question 3). The same motives that lead consumers to buy organic foods drive their intent to purchase organic wines [

30,

35]. Barber et al. [

51] and Schäufele and Hamm [

55] reported that people with strong environmental orientations are more willing to buy organic wine. In the present study, participants who claimed to purchase organic wine stated that they consumed the product because it is more environmentally friendly. In contrast to Delmas and Grant’s [

27] finding, because it serves as a motive for buying organic wines, environmental protection is associated with the production of organic wines. Similarities were found in the participants’ responses to animal welfare [

27], as they did not associate animal welfare with the production of organic wine. While the focus groups did not confirm any positive influence on buying frequency [

62], wine knowledge has been proven to significantly influence attitudes about organic wine [

6].

The barriers to purchasing organic wine are similar to those for buying organic food. These include poor knowledge [

34], lack of trust [

37] and higher prices [

9,

30,

31]. Tasting organic wine can positively or negatively impact consumers’ quality perception when they have little knowledge about organic wine [

27]. The expectation that organic wine is higher in quality and tastes better can be confounded if the product is tasted. Although higher prices did not serve as a barrier for the participants in Munich, they did for the participants in Berlin and Frankfurt.

The acceptance tests showed that the awareness, consideration and willingness to pay a premium for organic wine could be increased by expanding consumers´ knowledge about wine production and organic wine production with facts and pictures (Research Quest 4). The female participants proved to be especially open to changing their purchasing behaviours and expressed interest in buying and paying more for organic wine. Indeed, the results of several studies have shown that the consumers of sustainable or organic wine are primarily female [

51,

65].

The present study can help to identify the relevant barriers to buying organic food and wine. The results also indicate that the demand for organic wine can be increased by improving its visibility, increasing knowledge about wine and organic wine production and using pictures to promote it. Because not all consumers view the organic attribute positively, organic associations should provide educational opportunities to improve the overall perception of organic certifications. Because female and younger target groups appear to be more open to buying organic wine than older male wine consumers, this target group should be given specific attention.

In sum, we can make the following practical recommendations for producers, retailers and organic associations: (1) Increase the visibility of organic certification. By designating wines as organic on the front label, adding an organic banderole or providing information at the point of sale, awareness of the organic attribute can be improved during wine purchasing decisions. (2) Actively communicate about organic wine production. Poor knowledge and distrust about (organic) wine production need to be addressed. An information campaign could be conducted to increase familiarity, knowledge and, therefore, awareness. By making vineyard management efforts visible, consumers can be made aware of the necessary workload, increasing their willingness to pay.

We conducted a high number of focus group discussions in different locations, using participants of different genders and ages to close the gap in qualitative research on German wine consumers and their attitudes towards organic wine. Although this pattern cannot be considered representative, this was not our intention since our approach was qualitative.

The simulation of the purchasing decision functioned as a snapshot of the participants’ spontaneous reactions and was used to introduce the topic. However, it does not facilitate generalization, as the number of wines offered by retailers is usually much larger. During focus group discussions, participants´ answers can be influenced by social expectations. Nonetheless, this study provides more detailed information about consumer attitudes about the organic attribute and their knowledge about organic wine. The results should be verified by a quantitative survey. By collecting data about potential target groups, their knowledge and personal attitudes, sales and promotion strategies can be created to increase the active demand for organic wine.