Abstract

To what extent are the values of employees and employers aligned in the context of sustainability and how might this be assessed? These are the main research questions in a case study involving a Swedish Small to Medium Enterprise (SME) with ambitions to become more ‘sustainable’. The wider context of the paper is the alignment of managerial and employee values for organisational sustainability. Specifically, the study applies and assesses Barrett’s concept of Organisational Consciousness as a level-based approach to sustainability values, which we argue is based on an integration of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and Wilber’s Integral metatheory. Quantifying the incidence of references to various values elicited in interviews, the study demonstrates: the limited salience of Barrett’s themes (‘attributes’) for employees; the divergent perspectives in participants’ personal and organisational lives. While normatively affirming Barrett’s overall approach, we observe that most organisations are likely to be a considerable distance from Barrett’s higher levels. How one interprets this is debatable: it may be concluded that Barrett’s framework is overambitious or that organisations need to: (i) broaden their understanding of sustainability and (ii) nurture alignment between personal and organisational values.

1. Introduction

The culmination of global efforts to agree to Agenda 2030 [1] confirmed that collectively as a global community, organisations must transform how they conduct their business. Yet, according to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2018 [2], very few countries, regions, cities, communities or businesses have demonstrated the possibility of such transformation. Part of this challenge is that organisations must not only achieve financial success, but they must also move beyond mere environmental compliance, engaging in transformative change to achieve a higher degree of organisational sustainability [3]. Van Marrewijk and Werre [4] describe such a level as that of the global sustaining organisation, whereby “sustainability is embedded within all aspects of the organisation and is seen in global and intergenerational terms” [5] (p. 193). Yet, in order to make such a transformative change, organisations will have to make a shift in their fundamental activities, their systems, their cultures and their beliefs [6]. To do so, in turn, they must address both microlevel individual behaviour as well as organisational-level transformation characteristics [5], with strategic change beginning at the individual level [7].

Yet, theorisation of connections between individual-level processes and organisational-level sustainability transformations in the sense of strategic reorientation is relatively under researched, particularly in the growing research field of sustainability transitions. Therefore, the role of individual actors and agency in transitions is acknowledged [8]; however, both the role of organisational change management [9] and the role of actor-centered perspectives are under researched [10].

Ives, Freeth and Fischer [11] argue similarly. First, that transformation and change for greater sustainability has nearly neglected the interior–individual domain, and second, that one dimension that is particularly relevant is that of values [11]. It is important to note here that it is the development and evolution of individuals and organisations towards higher-level values that is considered here, not the construction of behavioral models relating to attitudes and norms, on which there is a large literature focusing on individuals in relation to sustainability (e.g., [12]).

Our focus here is on the alignment of personal and organisational sustainability values in an organisational context and, more specifically, on the potential value of a framework developed for assessing and supporting progress towards this and related values, namely Barrett’s organisational values framework [13].

Although there are two well-known frameworks for assessing organisational values, namely, the Competing Values Framework (CVF model) presented by Quinn and Rohrbaugh [14] as well as Schwartz’s values model [15], here we respond to the reservations of Malbašić, Rey and Potočan [16] around the usefulness of those frameworks in a practical business setting. The latter indicate through their study how a mission-based (i.e., end-point directed) model of organisational values is likely to be more useful in actual business practice than models posed in the CVF and by Schwartz. Malbašić, Rey and Potočan [16] argue for a greater integration of the value frameworks posed by CVF and Schwartz, to provide a mission-based model of organisational values based on a distinction between self-orientation and social orientation (organisational orientation towards environment), and stability and progress (organisational attitude towards changes). Nonetheless, the latter mission-based model does not aim to address the values of individual employees, and furthermore, lacks testing in a business setting. Given this, we explore the applicability of Barrett’s organisational values framework, which has been applied in business contexts as a contribution to the field of organisational transformation for sustainability.

One of the advantages of Barrett’s model is that he connects the personal–individual level to that of the organisation, in the context of higher-level norms relating to the welfare of wider society, including future generations. Barrett [17] argues that to gauge an organisation’s readiness for transformative change, one of the key performance indicators is the degree of alignment between personal values, current organisational values and desired organisational values. In this respect, he reflects a proposition shared by others, namely that the process of clarifying and aligning values arguably lies at the centre of organisational success [18]. Previous studies have found that managers with congruence and clarity amongst their personal and organisational values reported the highest levels of commitment and organisational success, as compared to those lacking such congruence and clarity [19]. Indeed, Erdogan, Kraimer and Liden [20] demonstrated that values and person–organisational fit have a significant impact on many aspects of organisational behaviour. For instance, when an organisation cultivates alignment between individual and organisational values, it induces more positive employee attitudes such as organisational commitment [21], reduced turnover [22] and job satisfaction [23]. Similarly, Jung and Avolio [24] found that an increased level of values congruence led to an increase in performance, commitment and intentions of employees to remain.

Despite a significant body of literature that, as documented above, has focused on individual versus organisational values to date, there have been only a few studies investigating the importance of values’ alignment with regard to sustainability in an organisational context. Moreover, Barrett’s framework in particular has, to our knowledge, not been assessed for its operational value vis a vis sustainability. Typical studies on values alignment usually relate to general values and to the achievement of general business goals, rather than being more specific to ambitions of an organisation becoming a global sustaining organisation (e.g., [25]).

Indeed, literature on the importance of value clarification and values alignment for organisational sustainability transformation processes is sparse in the sustainable business literature. For instance, much of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) literature focuses on making structural changes such as with sustainable business models. Moreover, of those studies that explore personal and organisational value alignment for sustainability (e.g., [26]), none incorporate a future dimension, i.e., they fail to investigate alignment with desired, future organisational values. That being said, there is a growing body of literature that focuses on supporting individuals in change processes for greater organisational sustainability; however, it does so by addressing competences for sustainability, mostly from an educational perspective [27,28,29]. Branson [30] argues that values alignment between the individual and the organisation is commonly overlooked, and that too much emphasis is placed on the structural and functional components of organisations. This is indeed surprising given that Rice and Marlow [31] argue that a lack of alignment is “the silent killer” of engagement (p. 140). Rice and Marlow [31] claim that misalignment is so easily overlooked in the engagement equation because (i) leaders assume alignment exists and (ii) definitions of engagement focus on job satisfaction, rather than addressing contribution and performance.

Given these gaps, this study takes an exploratory approach, rather than robust theory development to: (i) address the extent of values alignment between employees and their organisation, in the context of sustainability; (ii) assess a framework that could prove utility in assessing such alignment in the process of organisational transformation for greater sustainability; (iii) draw inferences regarding the options organisations have in terms of overcoming barriers in their transformation processes towards a higher degree of organisational sustainability.

To address these study objectives, we used a case study of a small Swedish business. Semi structured interviews and content analysis were utilised with the managers and other employees in the business to explore the stated research objectives. Illustrative diagrams were produced to enable a visual representation of the interview data.

Following the analysis, the findings indicate a lack of alignment amongst personal and organisational values of sustainability within the management team and limited alignment of values with the nonmanagement personnel. The application of using Barrett’s [17] OC model to assess the level of impact an organisation is able to have on greater societal sustainability was normatively affirmed; however, we observed that most organisations are likely to be a considerable distance from Barrett’s [17] higher levels. As a single firm case study, we do not claim wide generalisability of the empirical findings, but we do suggest that the general findings, which we highlight, will be widely relevant. Finally, we believe this study contributes to the empirical gap of how organisations are to transform to achieve a greater impact on societal sustainability by offering a (potentially) overlooked approach that could be worth further exploration.

The paper begins with establishing the theoretical context of Barrett’s OC model, its connection to existing literature and a description of the model itself (Section 2). From there, the design of the research and utilised methods are described (Section 3), followed by results (Section 4). A discussion of the results is provided in Section 5 with conclusions and suggestions for further work in Section 6.

2. Theoretical Context

The framework evaluated here, Barrett’s Organisational Consciousness (OC) Model [32], can be most immediately set in the context of the small literature on organisational values and ‘consciousness’, in the sense of collective awareness within the organisation—which in turn may constrain or liberate the individuals therein [33]. The purposes of Barrett’s model also relate to question of what motivates sustainability-related employees and the wider psychological dimensions of corporate sustainability management [34]. A key premise of Barrett’s approach is that individual and organisational values need to be aligned for organisational effectiveness [21], and this too has its own area of study [30], often appealing to Wilber’s integral metatheory [19,35,36].

Rooted in organisational development literature, Wilber’s integral metatheory [35] is intended to be applied at any macro-, meso- or microlevel of an organisational system to describe alternative organisational development paths [6]. For instance, Landrum and Gardner [7] used Wilber’s Integral theory to describe the strategic changes required of organisations seeking to lead in organisational sustainability. Wilber’s integral theory consists of quadrants based on: (i) an axis of the interior–exterior dimensions between the inner world of subjectivity and the outer world of objectivity; (ii) an axis of individual–communal dimensions referring to the relationship between individual identity or agency; social identity or communality. The consciousness quadrant represents the interior of the individual, while the behavioral quadrant represents the exterior of the individual. The cultural quadrants stem from the interior of the communal dimension, while the social quadrant represents the exterior of the communal dimension. Wilber’s integral theory [35] views the interaction of these dimensions as providing the fundamental domain through which all developmental change can be represented and assumes that change in one quadrant will affect functioning of the other three quadrants [6]. For strategic change to occur, all four quadrants must, therefore, be addressed, with change beginning at the inner individual level yet continuing to affect change in all other quadrants [7].

Within each of Wilber’s [37] quadrants, there exist several development levels and trajectories that help to guide our understanding of human development. This reflects the way in which Wilber draws on multiple perspectives within both psychology and sociology to propose a spectrum model of consciousness that includes what is intended to be the full range of developmental potentials of which human consciousness is capable. Wilber proposes that these basic levels and growth patterns can be observed in individuals as well as collective groups of individuals. The endpoint of the final level is labeled the trans egoic identity, which describes a pluralistic state with meta values, social awareness and responsibility with a collective purpose/mission committed to holistic community and global development. In other words, the final level connects with Van Marrewijk and Werre’s [4] concept of a global sustaining organisation, which encompasses similar ideas.

Barrett’s Organisational Consciousness (OC) Model

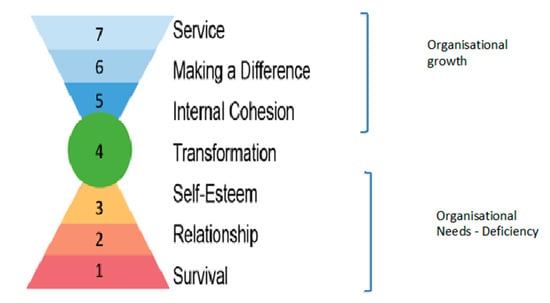

Arguably, in his model of Organisational Consciousness (OC), Barrett [17] operationalises both Wilber’s theory and Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a theory of human motivation [38]. In the OC model, Barrett connects individual developmental levels to organisational capabilities for transformation and change within a sustainability oriented framework through construction of a seven level model that relies on the fulfillment and progression of various needs within each level in order to reach the last level—that of being of service to humanity and the planet—which is only possible with a deep transformational change within an organisation in the context of sustainability. Figure 1 summarises the OC model, which should be read from bottom to top, starting with the first three levels of: (i) Survival, (ii) Relationship, (iii) Self-Esteem (‘organisational basic needs’). These levels are intended to address the fundamental basic needs of the organisation: those of financial stability, employee and customer loyalty, efficiency and effectiveness of systems and processes. To clarify, Barrett’s framework [17] relates Level 3—Self Esteem to systems and processes, in the sense that such structures “create order, support the performance of the organisation and enhance employee pride” [17] (p. 67).

Figure 1.

Barrett’s [17] Organisational Consciousness Model (reproduced with permission).

The lower levels focus on the self-interests of the organisation and its shareholders [17]. The higher levels, (v) Internal Cohesion, (vi) Making a Difference and (vii) Service, are referred to as the organisation’s “growth” needs, focusing on “cultural cohesion and alignment, building mutually beneficial alliances and partnerships, and, long-term sustainability and social responsibility” (‘organisational growth needs’). To further explain the relationship between Level 6—Making a Difference and building mutually beneficial alliances and partnerships, Barrett [17] (p. 66) describes that mastering Level 6, “means you are able to connect with others so you can actualise your sense of purpose by making a difference in the world”. Similarly, for Level 7—Service, long-term sustainability and social responsibility can be achieved when “making a difference becomes a way of life and you embrace the concept of self-less service” [17] (p. 66). Nevertheless, Barrett posits that when these needs from all levels are met, they perpetuate deeper levels of commitment and motivation. The fourth level, Transformation, is a bridge between the three lower levels and the three higher levels, representing a shift in modus operandi. This is a shift from a culture rooted in fulfilling basic survival needs, to one of empowerment and “responsible freedom”.

The OC model has been used by practitioners to provide an evaluation of areas that need development to support an organisation’s performance as it relates to delivery of its products and services, and ultimately its organisational goals. The factors that are used for such an evaluation are: (i) the degree of alignment between personal values, current organisational values and desired organisational values; (ii) the presence of limiting cultural factors such as blame, hierarchy and corruption, or rather, the degree of cultural entropy. Here, we adopted a similar operationalisation to [39], but rather than using a structured questionnaire, we applied quantified content analysis to semi structured interviews, as described below, principally because such interviews allow respondents to speak in their own terms, stating what is important to them without priming.

Box 1 describes Barrett’s seven levels of organisational consciousness in more detail, along with factors that limit progress through these levels [17]. In total, there are 37 attributes with a positive focus and seven limiting attributes. It is levels 6 and 7 where considerations of environmental and social awareness and well-being feature, alongside considerations of future generations. Most definitions of sustainability explicitly include not only protective environmental and social norms, but also assume some form of economic and material well-being however this is conceived. Moreover, there is arguably a case for minimising perceptions of a disconnect between sustainability framing and the more familiar values of quality, service and so on that businesses have been familiar with for many decades. That is, there is a case for mainstreaming sustainability values through such connections [40] and also for connecting sustainability to more widely embedded societal discourses and interests [41]. Accordingly, we focus here not only on the higher levels but all of the levels, specifically as regards: (a) the extent to which individuals in an organisation refer to values that can be placed in each category and (b) the extent of alignment between personal, perceived present organisational and perceived desired organisational values.

Box 1. Barrett’s [17] seven levels of organisational consciousness and attributes. (Note: Barrett [17] updates the phrasing used in Box 1, which is from an earlier version of the framework; the terms used in Barrett [17] are largely synonyms of the terms used here, with slight differences).

- Level 7: Service

- Social responsibility, future generations, long-term perspective, ethics, compassion, humility

- Level 6: Making a Difference

- Environmental awareness, community involvement, employee fulfillment, coaching/mentoring

- Level 5: Internal Cohesion

- Shared vision and values, commitment, integrity, trust, passion, creativity, openness, transparency

- Level 4: Transformation

- Accountability, adaptability, empowerment, teamwork, goal orientation, personal growth

- Level 3: Self-Esteem

- Systems, processes, quality, best practices, pride in performance

- Limiting factors: Complacency, bureaucracy

- Level 2: Relationship

- Loyalty, open communication, customer satisfaction

- Limiting factors: Blame, manipulation

- Level 1: Survival

- Shareholder value, organisational growth

- Limiting factors: control, corruption, greed

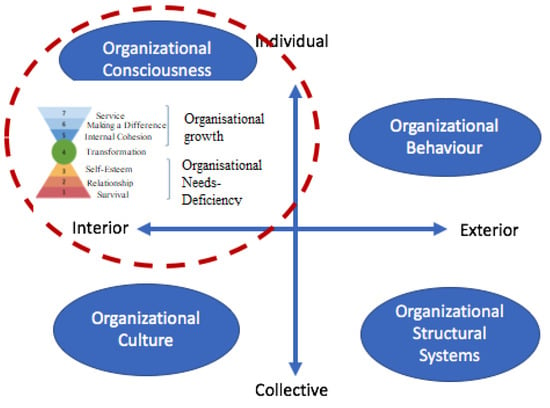

Figure 2 integrates Barrett’s OC model into Wilber’s framework, locating Barrett’s seven levels of organisational consciousness in the first quadrant. This positioning emphasises the focus on the interior vs. exterior as well as individual vs. collective dimension of Barrett’s model. The emphasis in the OC model is on the inner world of subjectivity. The consciousness quadrant represents the interior of the individual, while the behavioral quadrant represents the exterior of the individual.

Figure 2.

Positioning of Barrett’s Organisational Consciousness model within Wilber’s Integral Theory for Whole System Change.

3. Research Design and Methods

The research design is case study-based and utilises in-company interviews with the intention to operationalise and critically evaluate Barrett’s [17] framework as of potential utility in an organisational sustainability context. Analysis follows a deductive content analysis methodology [42], in this case qualitative with simple quantification of the number of participants referring to specific types of values. Case studies are widely used in organisational studies [43,44] and in combination with content analysis, case studies help to understand complex social phenomena [45]. Hamm, MacLean, Kikulis and Thibault [46] illustrate the value of using qualitative research methods specifically to achieve an understanding of value congruence. To this we added simple quantification, as this helped to further reveal and assess the degree of value alignment, while the qualitative responses helped us to understand the underlying reasoning of the interviewees.

Regarding issues of generalisability, here, we were not seeking to make cross-case claims. We reinterpreted an existing framework for an application beyond its original purpose and assessed the performance of this framework. Our purpose was to explore the types of issues that arise when beginning to extend the application of the framework, as a precursor to cross-case work. Nonetheless, we would suggest that tentative claims towards limited generalisability can be made: SMEs, despite their heterogeneity, do have some structural characteristics in common. Similarly, companies in general do experience the types of competing logics, internal and external pressures that become evident here through interviewing. Overall, the research design is exploratory and aims to meet a criterion of plausibility rather than, at this stage, robust theory development [47].

3.1. Case Study Company

The organisation used for the case study is a small company (approximately 30–35 employees) in the real estate and building sector, situated on the campus of a Swedish university. The company, anonymised as “M-Lab”, declared a vision of sustainability so as to support and align with the university’s ambition. At the time of study, it was in the process of adopting sustainability initiatives and in 2015 opened a role of Business and Sustainability Manager. The company has also worked with external consultants who have conducted interviews with external stakeholders to better understand what their sustainability expectations of the M-Lab are, and who have conducted an internal online survey with all employees to obtain an understanding of current sustainability perspectives. In addition, M-Lab was finalising four sustainability goals for the company to facilitate greater internal cohesion. Finally, twice a year, the M-Lab aims to hold full-day workshops on sustainability for all employees.

3.2. Interviews

The management team comprised most of the interviewee set, on the premise that this group in particular, by virtue of their positional authority, should have alignment with the organisational goal of sustainability and indeed with the other goals of the organisation. This focus follows Rickaby, Glass, Mills and Mccarthy [26], who also chose to only study professional and managerial roles, due to their impact on decision making, and as they are likely to directly or indirectly influence project/company performance with their own personal values. Eide, Saether and Aspelund, [48] furthered this by illustrating the “significant and strong direct relationship that exists between leaders’ personal motivation for sustainability and their firms’ strategic sustainability practices” (p. 6). A total of ten semi structured interviews were conducted. A guide for the interviews can be found in Appendix A.

Eight interviews were undertaken with the management team and two with other employees to obtain a complementary point of view. The participants selected for interviews were recommended from the key organisational contact of the researchers as key decision makers in managerial questions. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. The interviews were conducted between March and May of 2016. It should be noted that the interviews are used to assess a framework rather than report the current state of a company per se.

It should be emphasised that the aim here was not to representatively sample the entire management team or workforce, nor to present M-Lab as being necessarily representative of other firms. Rather, the intention was to assess Barrett’s framework empirically, and to set his framework in the context of both its theoretical antecedents and the wider literature on value alignment as a precondition for organisational change—in this case for sustainability.

3.3. Data Analysis

Following Mayring [42] and a deductive qualitative content analysis approach, the interview texts were analysed specifically with the aim of identifying the degree of alignment among personal–individual and organisational values relating to sustainability—both current and desired. The majority of the analytic frame and hence codes were thus predetermined (i.e., a form of priori coding [49]), in that the coding frame mirrored the structure and content of Barrett’s framework. Nonetheless, the analytic design also allowed for open coding—i.e., for new codes arising from the data to be added [50].

Responses to relevant questions were coded in accordance with the attributes listed in Box 1 of Barrett’s OC model, cross-referenced to the three types of values requiring alignment (current personal, current organisational and desired organisational). Additionally, sustainability-related attributes referred to by the participants were also coded. Where statements matched more than one attribute, they were multiply coded. The number of participants making such statements, corresponding to each attribute, was then plotted as spider diagrams for rapid visual comprehension. This combination of categorical text analysis is a strength of quantitative content analysis methodology in that “it preserves the advantages of quantitative content analysis but at the same time applies a more qualitative text interpretation” [45] (p. 25). The statements affiliated with each attribute were then analysed in detail for their degree of specificity and repetition across all three sustainability perspectives to ascertain the degree of alignment among all three perspectives for each individual participant in the study.

4. Results

4.1. Level 1 Sustainability Perspectives: Survival

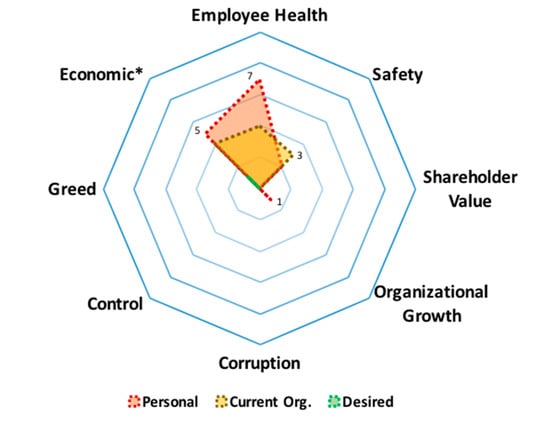

Beginning with Barrett’s level 1: Figure 3 shows limited coherence amongst the perspectives held by the participants across personal, current organisational and desired organisational levels. The most frequent reference is to employee health and financial well-being from a personal perspective.

Figure 3.

Level 1 sustainability perspectives: survival.

Regarding the attribute of safety, participants shared similar viewpoints as to what this means to them personally and what they feel it means to the M-Lab currently, as an attribute of sustainability. For instance, Manager G blended personal and current organisational sustainability by saying that “[personal sustainability is about] making campus safe” and “[that currently sustainability at the M-Lab] is about making safe environments; to make places where people like to be”. Meanwhile, Manager B blended concepts between the perspectives as well by stating, “[personal sustainability is about] wellbeing in the sense of social security” and “[current organisational sustainability] is about social wellness, social security”. No participants associated safety with a desired future state of the company.

The need for organisational growth was referred to by only one participant in relation to personal sustainability. However, half of the respondents identified economics and finance as important to personal aspects of sustainability, and so we added this to Figure 3. No participant made reference to shareholder value, nor any of the limiting factors such as greed, control or corruption, though this may be partly explained in terms of M-Lab being a small business without publicly traded shares.

4.2. Level 2 Sustainability Perspectives: Relationship

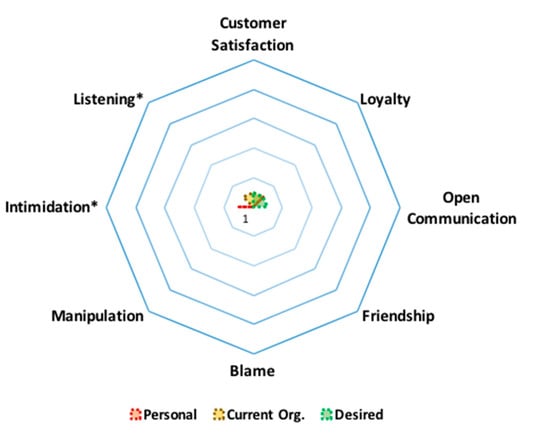

At level 2 as shown in Figure 4, there is a lack of alignment on any attribute and a lack of spontaneous association of relationships with sustainability. Nonetheless one participant connected customer satisfaction with sustainability, and another emphasised listening to customers as part of what they desire in terms of future organisational sustainability.

Figure 4.

Level 2 sustainability perspectives: relationship.

Barret’s attribute of loyalty was expressed at the level of personal sustainability by one participant (Employee B) stating: “everyone should participate in sustainability”, while another participant emphasised a combined sense of loyalty and collectivity stating that for current organisational sustainability, “we are here to support [the higher education institution’s] vision [for sustainability]” (Manager A). Another participant stated their desire for sustainability to “help each other” (Employee A).

There was a desire from one employee for open communication, while another expressed the attribute of listening being present in the current organisation, stating “there are lots of meeting to know what’s going on, what each other is doing [with regards to sustainability]” (Employee A).

There was no attribution of friendship with sustainability across any of the three perspectives. Finally, as a flipside of harmonious relationships, we added to level 2 one of Barret’s limiting factors, namely intimidation, as an inference from comments by one of the managers, who considered it acceptable to place employees under stress.

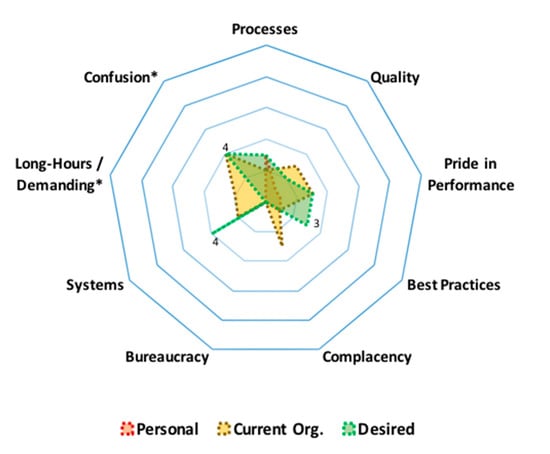

4.3. Level 3 Sustainability Perspectives: Self-Esteem

Level 3, represented in Figure 5, shows people to be experiencing several of Barrett’s limiting factors—confusion, long-hours/demanding environment and complacency—as well as referring to limitations in organisational processes, quality, pride in performance, best practices and systems. Participants referred to the lack of time for sustainability-related communication and also the limitations of that communication: “[specific people] are not given enough time and space to get their [sustainability] message out” (Employee A) and “sustainability is mostly words” (Manager H).

Figure 5.

Level 3 sustainability perspectives: self-esteem.

There was little reference to sustainability in relation to the personal perspective and little personal–organisational alignment where the former was referred to. For example, although Manager B stated that working with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) on a monthly basis was important for him/her, s/he also said that for the company, sustainability is primarily about the International Standards Organisation’s (ISO) Management system. Moreover, what the manager desired in terms of organisational sustainability was “making the environment and commuting more efficient”.

Regarding quality, Employee A stated that what they desire the M-Lab to achieve with regard to sustainability was that “[we] put good things in houses, not cheap things”. Pride in performance was reflected in the way Manager C “wants to be proud of my work” as part of his/her personal commitment to sustainability”. Manager A reflected his/her desire for M-Lab’s sustainability work to meet best practices, with the aspiration “that [this higher education institution] sets an international standard for how we work with sustainability”.

Manager D reflected his/her desire for appropriate systems for M-Lab’s sustainability work by stating “if it was in our routines, our project, it would be better; it can’t be something thought about separately, later on”. No statements were made reflecting bureaucracy within the M-Lab’s sustainability work.

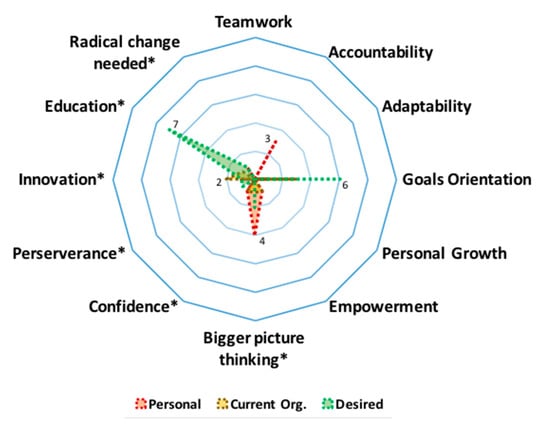

4.4. Level 4 Sustainability Perspectives: Transformation

Figure 6 shows the analysis of level 4 of Barrett’s OC model. Education for sustainability as well as orientation to explicit goals were considered by the majority of interviewees as essential and as such desired, yet not currently taking place in the company.

Figure 6.

Level 4 sustainability perspectives: transformation.

Bigger-picture thinking was referred to mainly from personal and aspirational organisational perspectives: “we must think outside the box” (Manager D, Employee A); and “everyone must think how we could it [sustainability] better.” (Manager D).

Participants connected accountability to sustainability from personal rather than organisational perspectives: “sustainability is about taking responsibility; being aware of actions” (Manager G).

Innovation was referred to by few interviewees, with such statements as “we must build houses that no one has done; testing something new” (Manager F) and “campus should be a test arena” (Manager A). We observed added radical change as an attribute, for its use in the context of personal sustainability and from a desirable standpoint: for example, “we must work 1000% more with energy” (Employee B). In the latter, there is conflation of (and hence alignment with) the personal and the organisational perspective.

Empowerment was lightly associated with sustainability, with one participant stating that “personal sustainability is about everyone having the courage to do what they want” (Manager G). Similarly, Manager G also stated that “personal sustainability is about individual self-confidence”.

Perseverance was referred to implicitly by Manager F stating that what he/she desires for M-Lab’s sustainability work is that “we keep doing what we’re doing now”.

No associations with sustainability across any of the three perspectives were made with the attributes of teamwork, adaptability or personal growth.

4.5. Level 5 Sustainability Perspectives: Internal Cohesion

Figure 7 illustrates level 5 of Barrett’s [17] model and focuses in particular on internal cohesion and building internal community. The interviews highlighted a strong desire for greater commitment and shared vision and values for organisational sustainability. This was not experienced as a present condition personally or organisationally but as a desired organisational state. Example statements include the wishes: “that everyone does their best and thinks about it on a daily basis” (Manager E) and “that we have developed clear goals by the end of the year and that all of us can clearly communicate them” (Manager A).

Figure 7.

Level 5 sustainability perspectives: internal cohesion.

Integrity was an attribute that participants desired for M-Lab’s sustainability work in the sense of sustainability being a genuine, core and integral part of the organisation’s work. For instance, “sustainability cannot be something that is thought about separately or later on” (Manager D) and “sustainability should be natural for everyone” (Employee B).

Trust was loosely associated with sustainability from a current organisational perspective, with Employee B stating “[in the M-Lab], everyone has the same worth, is treated equally and has the right to speak their mind”.

Another loose association with sustainability with the attribute of creativity came from Employee A, who was of the view that personal sustainability was about “thinking outside the box”.

No associations were made between sustainability and any of the three perspectives of sustainability amongst the attributes of transparency and passion. Only one participant associated openness with sustainability and from a desired organisational standpoint, saying: “we must be open to criticism” (Employee A).

Respect, fun, happiness, feedback and curiosity were additional attributes that participants associated with sustainability and expressed for instance, with the comments such as: “it is interesting and nice for us” (Manager F) and that “I hope that each individual is interested in sustainability” (Manager C). Three participants desired sustainability at M-Lab to be intuitive stating, for example, that: “sustainability should be intuitive” (Manager A, Employee B).

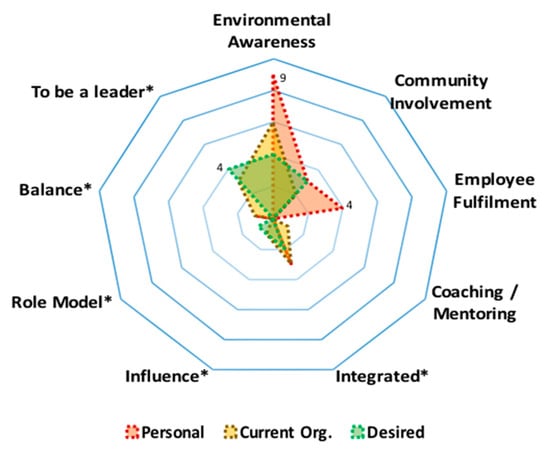

4.6. Level 6 Perspectives: Making a Difference

Figure 8, which relates to level 6 of OC’s model (making a difference, strategic alliances and partnerships), shows environmental awareness as the quality identified by the greatest number of participants, with nine out of the ten interviewees making this connection in relation to their personal perspective of sustainability. This was partly in relation to a desired organisational future: only six interviewees expressed the view that M-Lab currently expressed the attribute of environmental awareness. Interviewees had a general conception of environmental awareness from their personal perspective, using phrases such as: “endurance of the Earth” (Manager E) and “taking care of the environment” (Manager C). However, from their current organisational perspective and desired organisational perspective, respectively, their statements became more specific to the M-Lab, for example: “that we build in a sustainable way” (Manager C) and “that we can share buildings by getting more people into fewer buildings so we can reduce our earth footprint” (Manager A).

Figure 8.

Level 6 sustainability perspectives: making a difference.

Community involvement was fairly evenly associated with sustainability across the three perspectives by different interviewees. For instance, from a personal perspective, Manager G said sustainability is about “making campus spaces good places to meet”; from a current organisational perspective, Manager F said: “think about how we can meet each other” and from a desired organisational perspective, “open up more areas so more people can meet” (Manager B).

Employee fulfillment was identified as being important to sustainability from a personal perspective, but it lacked associations with current organisational sustainability and a desirable state for sustainability. From a personal perspective, Manager A stated: “what am I really working towards? We all want to feel good and have a good life”.

Coaching/mentoring was only mentioned by one participant with regard to sustainability and from a current organisational perspective. For instance, Employee E stated that s/he: “tries to coach [other employees] to keep all three pillars in balance; I try to discuss all together”.

Integration of different sustainability values was reflected in all three sustainability categories by different participants, and thus has been added here as an attribute. Relevant statements include: “you have to take care of all three aspects to do good things: social, economic, environment” (Manager D) and “all three pillars must be there when we make decisions, you can’t pull one out” (Manager E).

Influence was also an additional attribute that two participants associated with sustainability. For instance, “my desire is that every member in my team is able to influence the environment, the students, [the higher educational institution]” (Manager B).

The notion of role models was simply reflected by Employee B with his/her desire for the M-Lab to “be a role model” for sustainability.

Balance was reflected by such a statement as “economic, social, environment must all function together; must include all three when making decisions” (Manager E).

To-be-a-leader was reflected in the current and desired organisational perspective with such statements as, “we always say that we should be at the frontline of sustainability” (Manager D) and “that we can show the rest of the world how to do this” (Manager G).

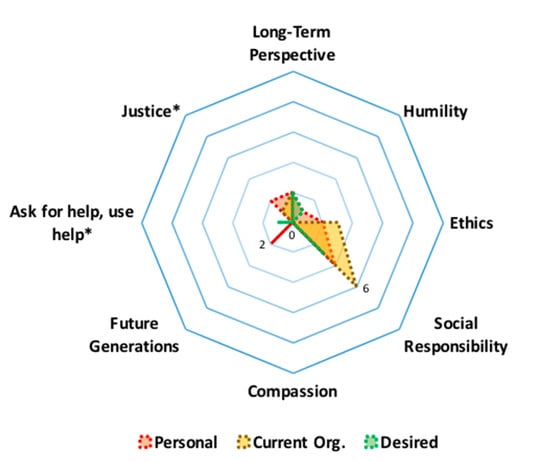

4.7. Level 7 Perspectives: Service

Finally, Figure 9 shows findings relating to level 7 of the OC model (service to humanity and the planet) and illustrates an emphasis by interviewees on social responsibility across all three sustainability perspectives, with the greatest emphasis being on the current organisational perspective. For instance, Manager G stated that: “we must work with suppliers so that material is not bought from countries with bad working practices”.

Figure 9.

Level 7 sustainability perspectives: service.

Ethics was also important to the current organisation’s sustainability work by stating: “workers must not be harmed, even if we import something” (Manager E).

Long term perspective was evenly identified across all three sustainability perspectives with one participant showing complete alignment by stating “long term perspective and thinking” for each sustainability perspective (Employee A). Although a similar attribute, future generations was only associated with sustainability from a personal perspective, for instance: “my kids and their future” (Manager A).

Humility was barely identified with sustainability; an exception was Manager C who stated that personally, he/she hopes “to have a better answer next year”.

Justice was also an additional term referenced by participants in the personal sustainability perspective and current organisational perspective, and thus is added here. Illustrative statements are: “equality in gender, in people; justice” (Manager A) and “everyone has the same worth, treated equally and has the right to speak their mind” (Employee B).

No participant made any association with sustainability and the attribute of compassion across any of the sustainability perspectives.

4.8. Summary of Results

In an ideal case, if an organisation was fully consistent with the highest level of Barrett’s framework (service to humanity and the planet), we would expect: (i) all employees of the organisation to clearly associate Barrett’s [17] 37 positive attributes with sustainability (a) personally, (b) with respect to the current state of the organisation and with respect to the desired state of the organisation; (ii) clear alignment of values (even if implicitly inferred) across all three perspectives for each participant in the context of sustainability; (iii) an absence of limiting factors such as blame, hierarchy and intimidation.

It is not surprising that this was not the case in the case study organisation: many factors mitigate against such an ideal performance, not the least of which is the commercial pressures of which for-profit businesses are by definition the subject. Of the 37 attributes in Barrett’s OC model, many were not referred to at all, implicitly or explicitly. For example, issues relating to the eight attributes of compassion, transparency, passion, teamwork, adaptability, personal growth, friendship, and shareholder value were not mentioned by any participant. Regarding friendship, this may not be surprising given that teamwork was also not referred to. Shareholder value is likely not referred to because the company is not publicly traded.

To this, we can add that there was no alignment across all three levels (personal present, organisational present and organisational future) for any of the management teams interviewed. The only alignment found was within two separate nonmanagement employees, in terms of environmental awareness and a long-term perspective.

That said, more than half of the participants did refer to a desire for greater education, commitment, shared vision and values and goal orientation in relation to organisational sustainability. This may relate to the particular case of M-Lab that it had not yet solidified its new sustainability goals and that the participants were seeking greater clarify and direction. Employee health was also referred to by more than half of the participants in terms of what sustainability means to them personally, although it was less well supported by what participants felt sustainability meant to the organisation currently and was not identified by any participant as a desirable quality for future organisational sustainability. Social responsibility was identified by more than half of the participants in terms of what sustainability means to the current organisation but less so from a personal perspective and even less for the desired, future organisational perspective. Few participants associated the attribute of environmental awareness with the current organisation and fewer still for the desired organisation.

The presence of limiting cultural factors, or, in Barrett’s terms, cultural entropy [51] in the sense of dispersed energy, constitute barriers that the M-Lab would have to overcome if they truly desire to advance their sustainability ambitions. Identified factors associated with these include: complacency, long-hours/demanding work environment, confusion and intimidation. The presence of these factors will restrict the performance of the M-Lab in the achievement of their sustainability ambitions, and it will be necessary to reduce these factors as much as possible so they do not become a hindrance.

5. Discussion

This study explored the application of Barrett’s framework of organisational values alignment for the purpose of evaluating and furthering progress towards organisational sustainability. We selected this particular framework on the basis of there being no other candidates with values alignment as both a core criterion and an objective, and with an embedded notion of evolution through normative levels. We found a lack of alignment amongst the management team of the selected company, and limited alignment amongst the employees. Among the questions that this raises are: What does it tell us about the company’s present and future performance vis a vis sustainability values? What does it tell us about the value of the framework for assessing this?

With regard to the first question, the exploratory research design allows only provisional insights, as the small number of employees interviewed was selected by a contact in the company as two who were particularly engaged in sustainability management. It would thus be misleading to assume that the management team had been successful at enabling or creating an environment that supports a degree of value alignment among their employees as a whole.

Nonetheless, the fact that none of the management team had alignment across their sustainability perspectives (personal, present company, future company) raises the issue of whether such alignment ought to be given more attention within the company. As Eide et al. [48] emphasize, corporate leaders’ personal motivations for directing and guiding a firm’s sustainability strategy are likely to be important for progressing the sustainability ambitions of a company. In short, the findings arguably raise issues for the company that are likely to be of wider relevance, but these are indicative only.

Regarding the framework, one can question whether it is reasonable to expect that many and all diverse aspects of an individual’s view of sustainability should be in full alignment with that of their organisation. Given the multiple, competing demands on both individuals and organisations, both of which are subject to a range of differing logics and pressures, a degree of inconsistency at all levels within and between individuals and organisations is very likely to be the norm. The issue, perhaps, is the degree of alignment that might be reasonably expected in the context of making progress towards the holding and enactment of sustainability values.

In addition to alignment, Barrett’s model advocates structural changes and leadership development/personal mastery in the sense of understanding oneself and the impacts of one’s actions. This concurs, for example, with Waite [52], who emphasizes the need for leadership to be nurtured at all levels of an organisation to foster greater sustainability. Similarly, Lozano [53] describes leadership as “the most important internal driver” (p. 291) for organisational change towards greater sustainability, and Ardichvili [54] argues for the pivotal role leadership development plays in transitioning organisations towards greater sustainability.

Supportive of this, Paarlberg and Perry [55] found that the source of values of high performing work teams come from internal personal goals rather than organisational goals, which underlines the need for understanding personal goals and values. In fact, an earlier study by Posner and Schmidt [19] found that without congruence between personal and organisational values, the next best thing to clarity around organisational values is to have clarity around one’s personal values for greater ethical values and practices.

There are several possible reasons for the distance between theory and empirics, in the sense of the moderate extent to which interviewees refer to Barrett’s attributes: (i) the theory might be considered overly ambitious or ideal; (ii) this particular organisation may be atypically poor in the terms in which we assess it; and/or (iii) the method of semi structured interviewing is inappropriate for revealing explicit and implicit values. We now consider each in turn.

Regarding (i), Barrett’s thesis [51] is that organisations need to progress in consciousness (values awareness) and achieve several forms of internal alignment, in order to realise their potential. Similar to Wilber’s integral theory [35] and Maslow’s theory of human motivation [38], which inform Barrett’s approach, this is a normatively-driven theory in the sense of having the achievement of inherent and explicit values as a purpose. As such, it arguably makes limited sense to critique the theory for setting out norms that are difficult to achieve or of which actors are unaware. The whole point of the theory is to encourage that awareness of alignment, with the norms assumed as a priori important. One might nonetheless empirically critique the more specific idea of a linear, phased progression through stages, but this is not our focus here.

Regarding point (ii), we have no reason to believe that the case study firm is unusual—although we cannot generalise in relation to the specific empirical detail from the case, the general finding that employees are unlikely to spontaneously refer to many of Barrett’s 44 terms is plausibly of wider applicability, because the firm is unlikely to be unusual in terms of its general characteristics [56]. Indeed, if it is in anyway atypical, it may be in having management with a significant interest in sustainability—something that should increase the likelihood of sustainability-informed responses.

Regarding point (iii), in general, methods should be consistent with research questions, i.e., capable of providing the information required to answer the questions posed. In this case, we were primarily concerned with the question of assessing the value of Barrett’s framework for, in turn, assessing organisational consciousness towards a set of values, including associated internal values alignment between individuals and the organisation. We chose semi structured interviews to limit priming and to avoid full provision of a priori response terms, as would be found in survey questions. The data gained, therefore, tell us that the personnel interviewed performed poorly in Barrett’s terms. Conversely, the theoretical antecedents that we identify for Barrett show the framework to be consistent with relevant literature. Given this and the points above, we would not infer that our methods of analysis are inappropriate for the task, but rather that, without strong priming or specification of terms, this SME is likely to be typical of many others in the respects found.

6. Conclusions and Further Work

This study sought to address an empirical gap relating to how organisations are to transform and achieve a higher degree of sustainability, with a particular emphasis on the alignment of individual and organisational transformation-related characteristics. To address this, we investigated an existing framework that has been applied by practitioners working on organisational values and transformation—Barrett’s Organisational Consciousness theory. We showed this to be theoretically located in the context of the wider empirics and theory of personal and organisational transformation and, in particular, based in part on Wilber’s Integral theory. The study particularly explored one of Barrett’s key premises for organisational transformation, namely that of alignment between personal values, current organisational values and desired organisational values. Rather than assuming that only Barrett’s higher levels of consciousness relate to sustainability, we argue that the concept of alignment between personal and organisational sustainability perspectives needs to become meaningful for people in their own terms and that – as such – it should not exclude the ‘lower’ levels of material security, legal compliance and what might be regarded as traditional values of firms, before the current understanding that the way we conduct our economic activity becomes increasingly untenable.

Through the use of relatively open and tangential questioning, we avoided over priming of participants regarding each of the attributes of Barrett’s model. We found that rather few of the attributes were spontaneously referred to at each ‘level’. Nonetheless, we assume that those attributes that were referred to are those that are salient to the individuals questioned, and our particular approach does not preclude the use of survey scales subsequently.

In terms of further work, there is potential to repeat the present study on a larger scale, in multiple firms and other cultural contexts, for comparison. There is also potential for deploying Barrett’s framework in a survey-based research design, following Ludolf, Silva, Gomes and Oliveira [39]. From a different methodological perspective, further research could also follow Mash, De Sa and Christodoulou [25], who advocate participatory action research with the management team over an extended period of time, to evaluate the effect of various interventions on the sustainability culture of the organisation. Whether qualitative or quantitative approaches are used, a baseline assessment prior to any interventions would be desirable.

More fundamental is the matter of whether Barrett’s [17] model would benefit from modification for organisational sustainability-specific application. Arguably this is so directions for further work might focus more on sustainability-specific values, skills and competences and ways of encouraging acquisition of these [57,58]. Use of a modified framework might need to be in an abbreviated form, given that there are already a large number of attributes. Such abbreviation has precedent in other work on values measurement—e.g., [59]. Further research might also want to connect with the growing body of literature on sustainable human resource management and determine what crossovers there may be to benefit the field of organisational change for sustainability. Overall, there remains much potential for further work in the latter field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.K., L.B., P.U.; methodology, data collection and analysis, L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K., L.B., P.U.; writing—review and editing, R.K., L.B., P.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the case study company, employees and managers for their time and assistance as well as Professors Christine Räisänen and John Holmberg for their supervision and support. Please note that the views represented in the paper are those of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview Guide

- Introduction/Background

- Could you tell me a bit about yourself: background, education, previous jobs?

- What do you do in your free time?

- What are your hobbies? What do you do outside of work?

- Do you belong to any networks outside or inside work?

- Could you please give me a description of your role here at M-lab?

- How long have you been working here for?

- Why did you choose to work here at M-lab? What role do you have?

- Could you please describe a typical day at M-lab for me?

- Sustainability—Personal Level

- In your own words, could you please describe what sustainability means to you?

- What three words come to your mind with sustainability? Could you please describe what each entails?

- Sustainability—Organisational Level

- Could you describe what sustainability means for M-lab today? How does M-lab work with sustainability today? Ask for specific/concrete examples!

- As an organisation, what do you desire for M-lab to achieve with regard to sustainability?

- In regards to sustainability, what do you expect of each individual here at M-lab?

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy, D.C.; Griffiths, A.; Benn, S. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability: A Guide for Leaders and Change Agents of the Future; Psychology Press, Routledge/Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.G. An integrative metatheory for organisational learning and sustainability in turbulent times. Learn. Organ. 2009, 16, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppe, R.; Edwards, M. Seeking the Holy Grail of organisational development: A synthesis of integral theory, spiral dynamics, corporate transformation and action inquiry. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E.; Gardner, C.L. Using integral theory to effect strategic change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2005, 18, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Bögel, P.; Dütschke, E. Thinking about individual actor-level perspectives in sociotechnical transitions: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.; Pereverza, K.; Upham, P.; Kordas, O. Linking socio-technical transition studies and organisational change management: Steps towards an integrative, multi-scale heuristic. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Bögel, P.; Johansen, K. Energy Transitions and Social Psychology: A Sociotechnical Perspective; Routledge Studies in Energy Transitions, Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781138311756. [Google Scholar]

- Ives, C.; Freeth, R.; Fischer, J. Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio 2019, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R. Culture and consciousness: Measuring spirituality in the workplace by mapping values. In Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781315703817. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E.; Rohrbaugh, J. A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malbašić, I.; Rey, C.; Potočan, V. Balanced Organizational Values: From Theory to Practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, R. The Values-Driven Organization: Cultural Health and Employee Well-Being as a Pathway to Sustainable Performance; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 1317193865. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, E.C.; Terblanche, F. Building organisational culture that stimulates creativity and innovation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2003, 6, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, B.Z.; Schmidt, W.H. Values congruence and differences between the interplay of personal and organizational value systems. J. Bus. Ethics 1993, 12, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B.; Kraimer, M.L.; Liden, R.C. Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: The compensatory roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support. Pers. Psychol. 2004, 57, 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.; Sullivan, R.; Buffton, B. Aligning individual and organisational values to support change. J. Chang. Manag. 2001, 2, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B. Value congruence and job satisfaction among nurses: A human relations perspective. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2004, 41, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Avolio, B.J. Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mash, R.; De Sa, A.; Christodoulou, M. How to change organisational culture: Action research in a South African public sector primary care facility. Afr. J. Prim. Heal. Care Fam. Med. 2016, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickaby, M.; Glass, J.; Mills, G.; McCarthy, S. Exploring Alignment of Personal Values in a Complex, Multi-Organisation Construction Project Environment; UCL: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; van Leur, S.; Lans, T.; Dentoni, D. Individual competencies for managers engaged in corporate sustainable management practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, C.M. Achieving organisational change through values alignment. J. Educ. Adm. 2008, 46, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, C.; Marlow, F.; Masarech, M.A. The Engagement Equation: Leadership Strategies for an Inspired Workforce; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 1118331990. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, R. Building a Values-Driven Organization; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006; ISBN 1136425179. [Google Scholar]

- Digha, M. Morgan’s Images of Organizations Analysis. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2014, 3, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.; Crane, A. Corporate Sustainability and the Individual: Understanding What Drives Sustainability Professionals as Change Agents. SSRN Electron. J. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilber, K. Introduction to integral theory and practice. J. Integr. Theory Pract. 2005, 1, 2–38. [Google Scholar]

- Florea, L.; Cheung, Y.; Herndon, N. For All Good Reasons: Role of Values in Organizational Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilber, K. An integral theory of consciousness. J. Conscious. Stud. 1997, 4, 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Eerven Ludolf, N.; do Carmo Silva, M.; Francisco Simões Gomes, C.; Martins Oliveira, V. The organizational culture and values alignment management importance for successful business. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 14, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, R.; Upham, P. A Model of Small Business and Sustainable Development: Values, Value Creation and the Limits to Codified Knowledge Tools. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship and Sustainability; Kyro, P., Fayolle, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chester, UK, 2015; pp. 275–296. ISBN 1849808244. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, J.; Larsson, J. A Sustainability Lighthouse—Supporting Transition Leadership and Conversations on Desirable Futures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Mayring Qualitative Content Analysis Basic Ideas of Content Analysis. Forum Qual. Sozialforsch. 2000, 7, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C.; Symon, G. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0761948872. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell, C.; Symon, G. Qualitative research in work contexts. Qual. Methods Organ. Res. 1994, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlbacher, F. The use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. In Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research; Institut für Qualitative Forschung: Berlin, Germany, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm, S.; MacLean, J.; Kikulis, L.; Thibault, L. Value Congruence in a Canadian Nonprofit Sport Organisation: A Case Study. Sport Manag. Rev. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden-Biddle, K.; Locke, K. Composing Qualitative Research; Amazon: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eide, A.E.; Saether, E.A.; Aspelund, A. An investigation of leaders’ motivation, intellectual leadership, and sustainability strategy in relation to Norwegian manufacturers’ performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2006; ISBN 0761991514. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, R. The New Leadership Paradigm; Fulfilling Books: Asheville, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, A.M. Leadership’s influence on innovation and sustainability: A review of the literature and implications for HRD. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Are companies planning their organisational changes for corporate sustainability? An analysis of three case studies on resistance to change and their strategies to overcome it. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardichvili, A. Sustainability or limitless expansion: Paradigm shift in HRD practice and teaching. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2012, 36, 873–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarlberg, L.E.; Perry, J.L. Values management: Aligning employee values and organization goals. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.W.; Wu, E.H. On generalising from single case studies: Epistemological reflections. J. Philos. Educ. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyness, L. Sustainability: What the entrepreneurship educators think. Educ. Train. 2015, 57, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, R.G.; Farber, V.A. In Alain Gibb’s footsteps: Evaluating alternative approaches to sustainable enterprise education (SEE). Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2016, 14, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R. An Analysis of the Predictive Validity of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale. J. Environ. Educ. 2003, 34, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).