Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Challenge–Hindrance Stressors

2.2. Challenge–Hindrance Stressors and Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior

2.3. Challenge–Hindrance Stressors and Emotions

2.4. Mediating Role of Emotions

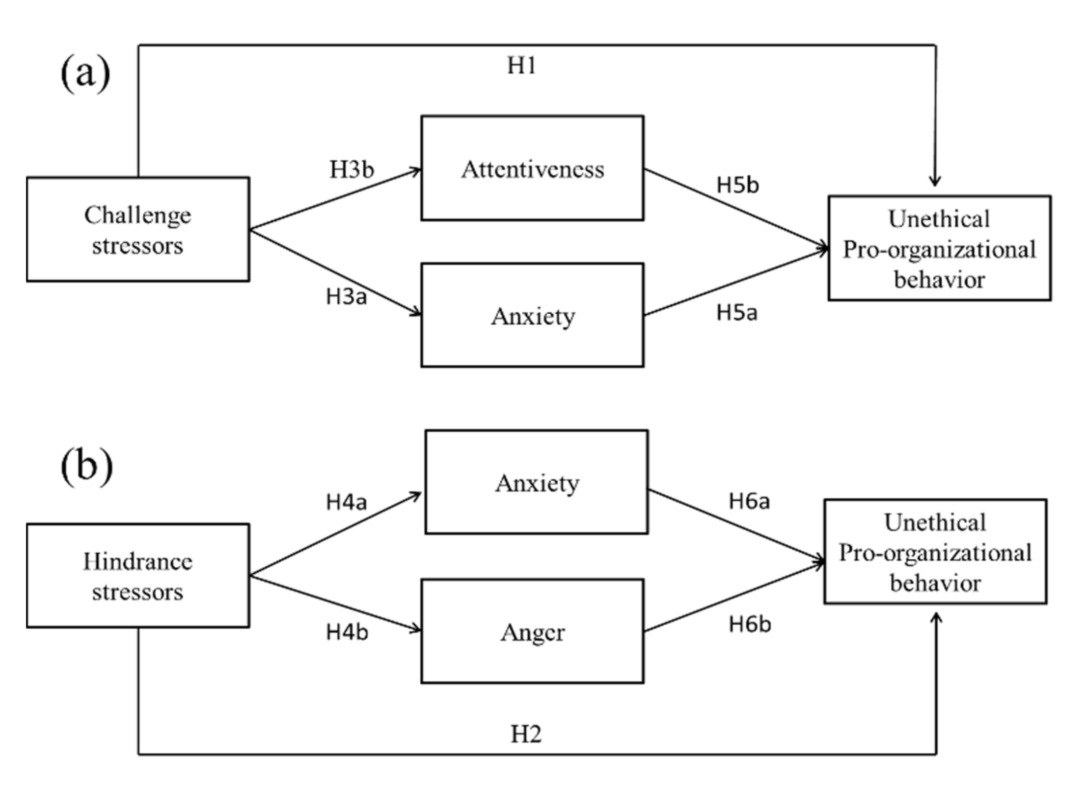

2.5. Research Model

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Challenge–Hindrance Stressors

3.2.2. Emotions

3.2.3. UPB

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Common Method Bias Testing

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

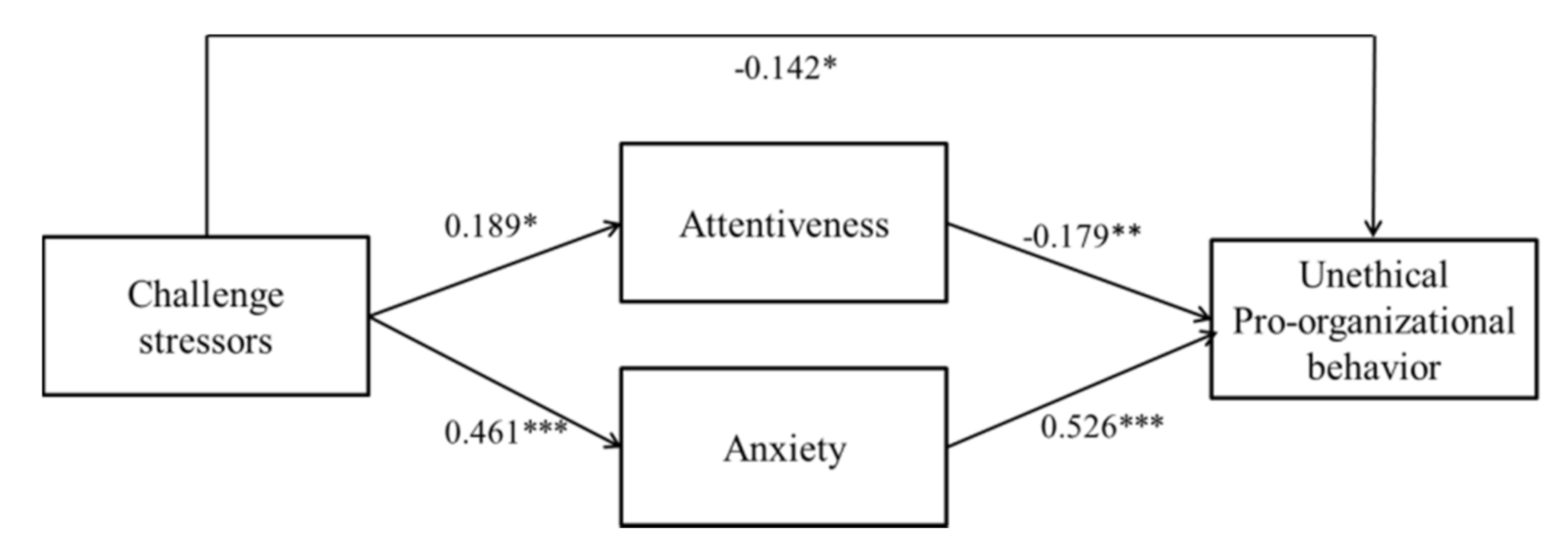

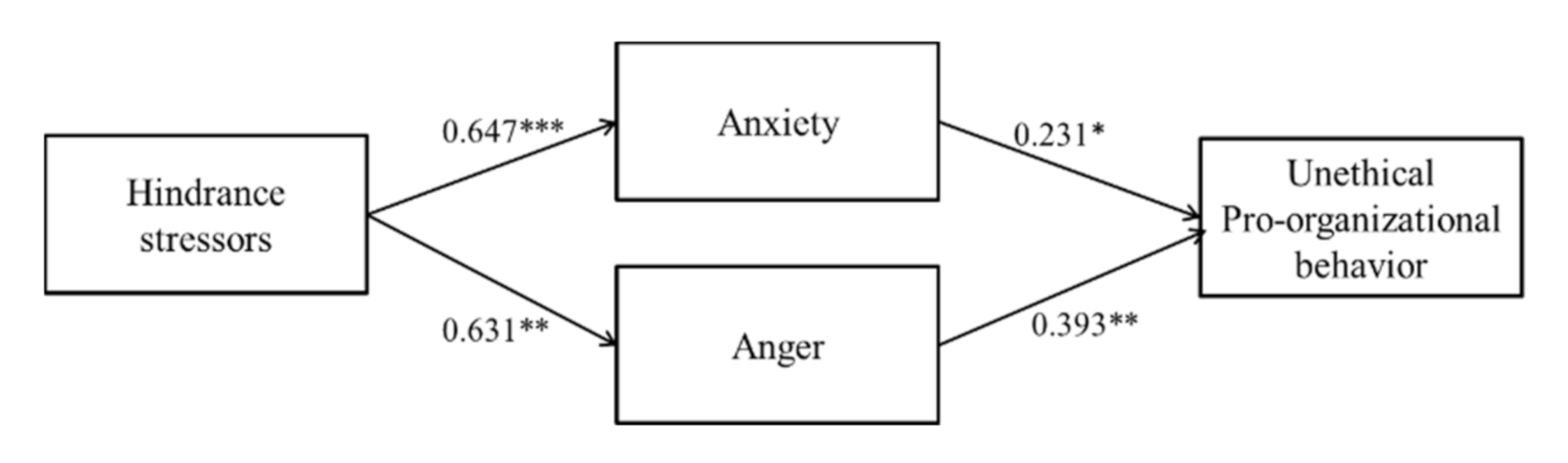

4.3. Test of Hypothesis

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gigol, T. Influence of authentic leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The intermediate role of work engagement. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; den Nieuwenboer, N.A.; Kish-Gephart, J.J. (Un) Ethical behavior in organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 635–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinsky, A.; Margolis, J. Necessary evils and interpersonal sensitivity in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B.; Mitchell, M.S. Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.A.; Ziegert, J.C.; Capitano, J. The effect of leadership style, framing, and promotion regulatory focus on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Sheldon, O.J. Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, D.T. The pathway to unethical pro-organizational behavior: Organizational identification as a joint function of work passion and trait mindfulness. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2016, 93, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating when and why psychological entitlement predicts unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.R.; Kacmar, K.M. Exploring the impact of job insecurity on employees’unethical behavior. Bus. Ethics Q. 2017, 27, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K. The direct and interactive effects of job insecurity and job embeddedness on unethical pro-organizational behavior. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1182–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Chen, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Why and when does job satisfaction promote unethical pro-organizational behaviours? Testing a moderated mediation model. Int. J. Psychol. 2018, 54, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, D.; Chudzicka-Czupała, A.; Chrupała-Pniak, M.; Mello, A.L.; Paruzel-Czachura, M. Work ethic and organizational commitment as conditions of unethical pro-organizational behavior: Do engaged workers break the ethical rules? Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2019, 27, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effelsberg, D.; Solga, M.; Gurt, J. Transformational leadership and follower’s unethical behavior for the benefit of the company: A two-study investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Newman, A.; Yu, J.; Xu, L. The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Linear or curvilinear effects? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Long, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, W. A social exchange perspective of employee–organization relationships and employee unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of individual moral identity. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, S.; Derfler-Rozin, R.; Pitesa, M.; Mitchell, M.S.; Pillutla, M.M. Unethical for the sake of the group: Risk of social exclusion and pro-group unethical behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhan, X. Performance pressure and unethical pro-organizational behavior: Based on cognitive appraisal theory of emotion. Chin. J. Manag. 2018, 15, 358–365. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Lv, Z. HPWS and unethical pro-organizational behavior: A moderated mediation model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Peterson, D.K. The effects of ethical pressure and power distance orientation on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The case of earnings management. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D.; Dormann, C.; Frese, M. Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research: A review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. J. Occup. Health Psych. 1996, 1, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.E.; Bhagat, R.S. Organizational stress, job satisfaction and job performance: Where do we go from here? J. Manag. 2016, 18, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Newman, J.E. Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: A facet analysis, model, and literature review. Pers. Psychol. 1978, 31, 665–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M.A.; Boswell, W.R.; Roehling, M.V.; Boudreau, J.W. An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.R.; Beehr, T.A.; Christiansen, N.D. Toward a better understanding of the effects of hindrance and challenge stressors on work behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, M.A. A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Stanton, K. Emotion blends and mixed emotions in the hierarchical structure of affect. Emot. Rev. 2017, 9, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.T.; McGraw, A.P. Further evidence for mixed emotions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, J.B.; Judge, T.A. Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; Shmueli, D.; Muraven, M. Restoring the self: Positive affect helps improve self-regulation following ego depletion. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychol. Inq. 1996, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Wood, C.; Stiff, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 495–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jex, S.M. Stress and Job Performance; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr, T.A.; Jex, S.M.; Stacy, B.A.; Murray, M.A. Work stressors and coworker support as predictors of individual strain and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Dwyer, D.J.; Jex, S.M. Relation of job stressors to affective, health, and performance outcomes: A comparison of multiple data sources. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, M.F.; Winefield, H.R.; Winefield, A.H.; Jonge, J. Psychosocial job strain and productivity in human service workers: A test of the demand-control-support model. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2000, 73, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Walsh, J.T.; Taber, T.D. Relationships of stress to individually and organizationally valued states: Higher order needs as a moderator. J. Appl. Psychol. 1976, 61, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; LePine, J.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Wei, F. It’s not fair … Or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor–job performance relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinard, M.B.; Yeager, P.C. Corporate Crime; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, M.E.; Ordonez, L.; Douma, B. Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 422–432. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.E. Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, G.; Czapinski, J. Positive-Negative Asymmetry in Evaluations: The Distinction between Affective and Informational Negativity Effects. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 1, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.C.; Chugh, D. Bounded ethicality: The perils of loss framing. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleef, G.A.V.; Dreu, C.K.W.D.; Manstead, A.S.R. An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 42, 45–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist, K.A.; Wager, T.D.; Kober, H.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Barrett, L.F. The brain basis of emotion: A meta-analytic review. Behav. Brain Sci. 2012, 35, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, A.P.; Eisenkraft, N. Positive is usually good, negative is not always bad: The effects of group affect on social integration and task performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, P.S.; Semmer, N.K.; Kälin, W.; Jacobshagen, N.; Meier, L.L. The ambivalence of challenge stressors: Time pressure associated with both negative and positive well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. Emotion and adaptation. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1993, 181, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fida, R.; Paciello, M.; Tramontano, C.; Fontaine, R.G.; Barbaranelli, C.; Farnese, M.L. An Integrative Approach to Understanding Counterproductive Work Behavior: The Roles of Stressors, Negative Emotions, and Moral Disengagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.R.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form; University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Perrewé, P.L.; Zellars, K.L. An examination of attributions and emotions in the transactional approach to the organizational stress process. J. Organ. Behav. 1999, 20, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, L.L.G.; Bekkers, V.; Vink, E.; Musheno, M. Coping during public service delivery: A conceptualization and systematic review of the literature. J. Publ. Adm. Res. Theor. 2015, 25, 1099–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, M.G.; Neves, P. When stressors make you work: Mechanisms linking challenge stressors to performance. Work Stress 2015, 29, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, T. Feeling bad: Antecedents and consequences of negative emotions in ongoing change. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 875–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, G. Helplessness: Theory and research in anxiety. In Anxiety: Current Trends in Theory and Research; Spielberger, C.D., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Grupe, D.W.; Nitschke, J.B. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G.H. Mood congruity of social judgments. In Emotion and Social Judgments; Forgas, J.P., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Elmsford, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, N. Feelings as Information: Informational and Motivational Functions of Affective States; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychol. Inq. 2003, 14, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulkin, J.; Thompson, B.L.; Rosen, J.B. Demythologizing the emotions: Adaptation, cognition, and visceral representations of emotion in the nervous system. Brain Cogn. 2003, 52, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, Q.; Luo, Y. Selected attentional bias in different level of trait anxiety. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2013, 45, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, R.J. Toward a science of mood regulation. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Crawford, E.R.; Rich, B.L. Turning their Pain to Gain: Charismatic Leader Influence on Follower Stress Appraisal and Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1036–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Chen, Z.; Lei, J. Inspire me to donate: The use of strength emotion in donation appeals. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; White, S. Handbook of Asian Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Chapter 11; pp. 315–347. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, A.; Isen, A.M. The influence of positive affect on the components of expectancy motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psych. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Baron, R. Positive affect as a factor in organizational behavior. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Cummings, L.L., Staw, B.W., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K. The influence of positive emotions on interpersonal trust: Clues effects. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2011, 43, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The value of positive emotions: The emerging science of positive psychology is coming to understand why it’s good to feel good. Am. Sci. 2003, 91, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Tiedens, L.Z. Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger’s influence on cognition. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2006, 19, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E. Clarifying the emotive functions of asymmetrical frontal cortical activity. Psychophysiology 2003, 40, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon Jones, E. On the relationship of frontal brain activity and anger: Examining the role of attitude toward anger. Cogn. Emot. 2004, 18, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Esteem threat, self-regulatory breakdown, and emotional distress as factors in self-defeating behavior. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 145–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, A.C.; He, W.; Yam, K.C.; Bolino, M.C.; Wei, W. Good actors but bad apples: Deviant consequences of daily impression management at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J.; Harrison, D.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J. Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 2011, 18, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Krull, J.L.; Lockwood, C.M. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev. Sci. 2000, 1, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | —— | ||||||||

| 2 Age | −0.105 | —— | |||||||

| 3 Job level | −0.104 | 0.099 | —— | ||||||

| 4 Challenge stressors | 0.034 | −0.040 | 0.194 ** | —— | |||||

| 5 Hindrance stressors | 0.100 | −0.015 | −0.060 | 0.426 ** | —— | ||||

| 6 Attentiveness | −0.071 | −0.046 | 0.152 * | 0.200 ** | −0.122 | —— | |||

| 7 Anxiety | −0.049 | −0.034 | 0.096 | 0.445 ** | 0.376 ** | 0.104 | —— | ||

| 8 Anger | 0.127 * | 0.029 | −0.144 * | 0.131 | 0.336 ** | −0.114 | 0.487 ** | —— | |

| 9 Unethical pro-organizational behavior | 0.066 | 0.003 | −0.212 ** | 0.036 | 0.299 ** | −0.150 * | 0.366 ** | 0.432 ** | —— |

| Mean | 1.460 | 2.560 | 1.430 | 3.140 | 2.823 | 3.578 | 2.818 | 2.107 | 2.410 |

| SD | 0.500 | 0.904 | 0.734 | 0.800 | 0.798 | 0.783 | 0.778 | 0.881 | 0.753 |

| Model | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | CS, AS, AR, UPB | 294.379 | 113 | 2.605 | 0.908 | 0.903 | 0.069 |

| CS + AS, AR, UPB | 468.170 | 116 | 4.036 | 0.765 | 0.731 | 0.113 | |

| CS + AS + AR, UPB | 536.276 | 118 | 4.545 | 0.704 | 0.687 | 0.124 | |

| CS + AS + AR + UPB | 694.034 | 119 | 5.832 | 0.528 | 0.434 | 0.145 | |

| Model 2 | HS, AR, AY, UPB | 151.473 | 84 | 1.803 | 0.923 | 0.911 | 0.050 |

| HS + AR, AY, UPB | 273.286 | 87 | 3.141 | 0.815 | 0.777 | 0.093 | |

| HS + AR + AY, UPB | 401.426 | 89 | 4.510 | 0.670 | 0.611 | 0.123 | |

| HS + AR + AY + UPB | 569.558 | 90 | 6.328 | 0.514 | 0.445 | 0.148 | |

| Model | Project | Effect Size | Bias Corrected 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Challenge stressors → unethical pro-organizational behavior | Total mediation effect | 0.209 | CI = [0.094, 0.372] | |

| Specific mediation effect | Path 1: Challenge stressors → attentiveness → unethical pro-organizational behavior | −0.034 | CI = [−0.107, −0.007] | |

| Path 2: Challenge stressors → anxiety → unethical pro-organizational behavior | 0.243 | CI = [0.128, 0.403] | ||

| Hindrance stressors → unethical pro-organizational behavior | Total mediation effect | 0.398 | CI = [0.212, 0.698] | |

| Specific mediation effect | Path 1: Hindrance stressors → anxiety → unethical pro-organizational behavior | 0.150 | CI = [0.037, 0.384] | |

| Path 2: Hindrance stressors → anger → unethical pro-organizational behavior | 0.248 | CI = [0.114, 0.491] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, L.; Wang, J. Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187576

Xu L, Wang J. Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187576

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Lin, and Jigan Wang. 2020. "Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187576

APA StyleXu, L., & Wang, J. (2020). Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability, 12(18), 7576. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187576