Building a Thriving Organization: The Antecedents of Job Engagement and Their Impact on Voice Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

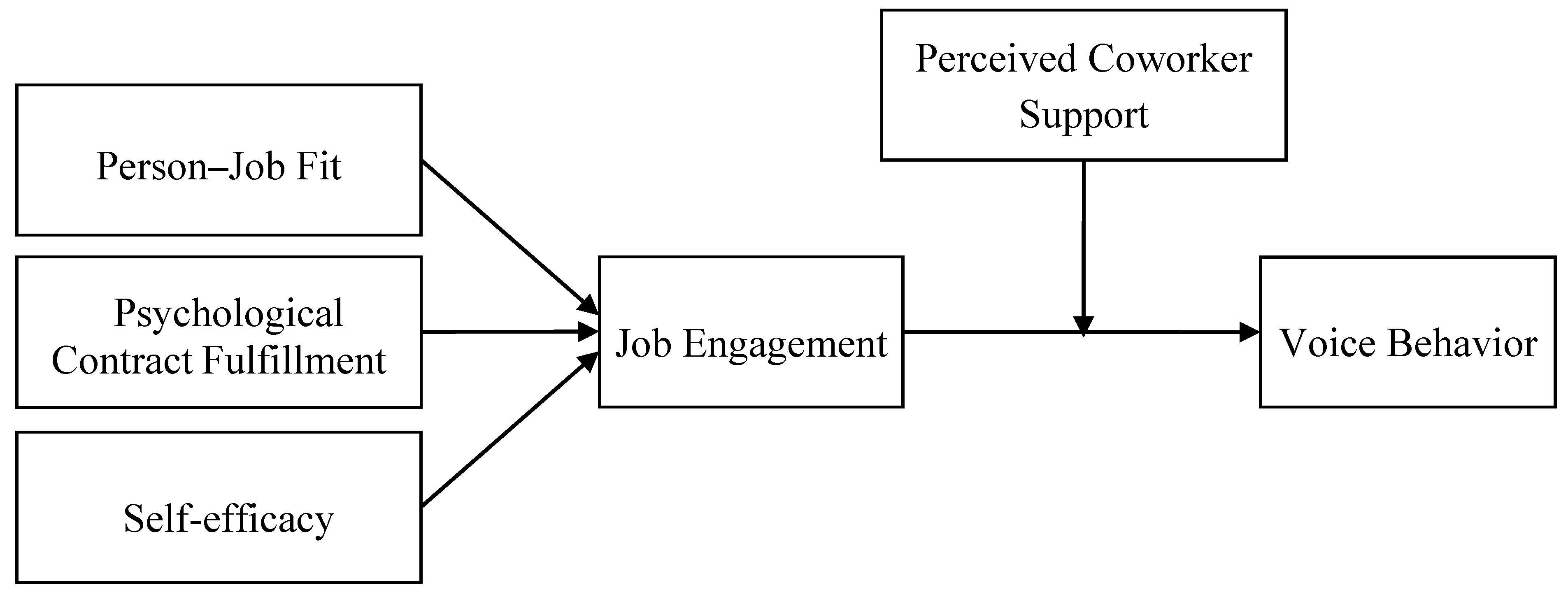

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Job Engagement and Antecedents

2.1.1. P–J Fit and Job engagement

2.1.2. Psychological Contract Fulfillment and Job Engagement

2.1.3. Self-Efficacy and Job Engagement

2.2. Job Engagement and Voice Behavior

2.3. Mediating Effect of Job Engagement

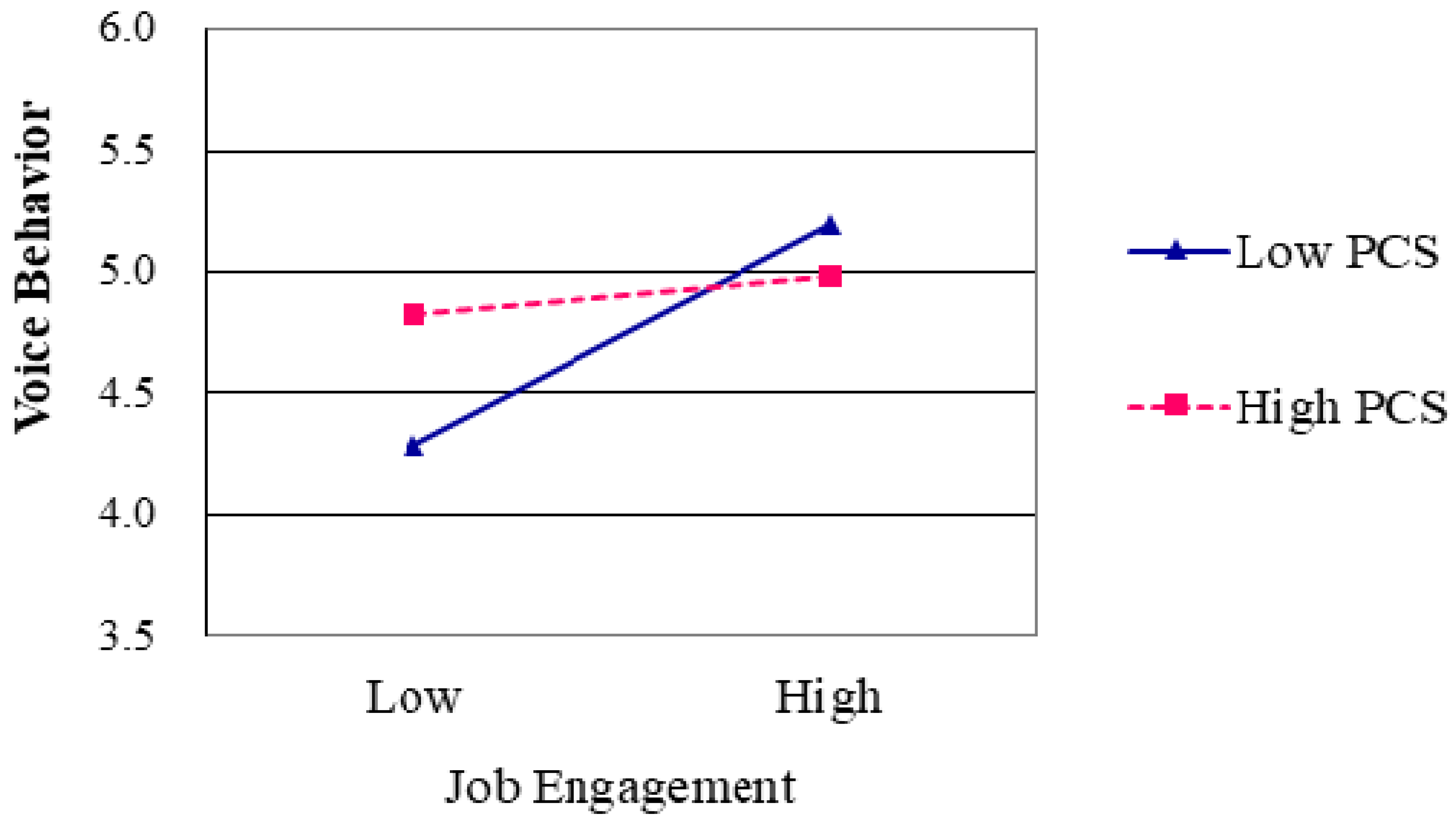

2.4. Moderating Effect of Perceived Coworker Support

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, W.; Khan, G.F.; Wood, J.; Mahmood, M.T. Employee engagement for sustainable organizations: Keyword analysis using social network analysis and burst detection approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafeshat, R.; Tanova, C. Servant leadership style and high-performance work system practices: Pathway to a sustainable jordanian airline industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Ohana, M. Perceived organizational support and well-being: A weekly study. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Vázquez, G.; Castro-Casal, C.; Álvarez-Pérez, D.; Río-Araújo, D. Promoting the sustainability of organizations: Contribution of transformational leadership to job engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4109. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance 2010. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behavior. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Truss, C.; Soane, E.C.; Rees, C.; Gatenby, M. The relationship between line manager behavior, perceived HRM practices, and individual performance: Examining the mediating role of engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 839–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, N.Z.A.; Arif, L.S.M. Employee engagement and employee voice. Development 2018, 7, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Harrison, D.A. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X. Effect of organizational justice on work engagement with psychological safety as a mediator: Evidence from China. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2016, 44, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Yen, C.H.; Tsai, F.C. Job crafting and job engagement: The mediating role of person-job fit. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 37, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuck, B.; Reio Jr, T.G.; Rocco, T.S. Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2011, 14, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Zeng, Y.; Higgs, M. The role of person-job fit in the relationship between transformational leadership and job engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, J. Linking empowering leadership and employee work engagement: The effects of person-job fit, person-group fit, and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D. Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, M.E.; Mosquera, P. Fostering work engagement: The role of the psychological contract. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayton, B.A.; Yalabik, Z.Y. Work engagement, psychological contract breach and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2382–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, P.M.; De Cooman, R.; Mol, S.T. Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: The influence of organizational tenure. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2013, 22, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ. Res. Methods. 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, S.; Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A.; Salanova, M. Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 825–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbula, S.; Guglielmi, D.; Schaufeli, W.B. A three-wave study of job resources, self-efficacy, and work engagement among Italian schoolteachers. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2011, 20, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, C.; Borgogni, L.; Di Tecco, C.; Schaufeli, W.B. What makes employees engaged with their work? The role of self-efficacy and employee’s perceptions of social context over time. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: The caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 2012, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Macey, W.H.; Schneider, B.; Barbera, K.M.; Young, S.A. Employee Engagement: Tools for Analysis, Practice, and Competitive Advantage; John Wiley & Sons: Malden, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hockey, G.R.J. Work environments and performance. In Work and Organizational Psychology a European Perspective; Chmiel, N., Ed.; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 206–230. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Predicting voice behavior in work groups. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B. Meaning, self, and motivation in organizations. Organ. Stud. 1991, 12, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Chen, H. Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearce, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Tripoli, A.M. Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: Does investment in employees pay off? Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1089–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Ecology of Stress; Hemisphere: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.; Chmiel, N.; Hershcovis, M.S.; Walls, M. Life on the line: Job demands, perceived co-worker support for safety, and hazardous work events. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.L.; Morrison, E.W. The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Preacher, K.J. Quantifying and testing indirect effects in simple mediation models when the constituent paths are nonlinear. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2010, 45, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; van den Heuvel, M. Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.G. A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Park, J. Examining structural relationships between work engagement, organizational.9 procedural justice, knowledge sharing, and innovative work behavior for sustainable organizations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Factors | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | △χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized Model | Six-Factor model: PJF, PCF, SEFF, JE, PCS, VB | 436.18 | 215 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.07 | |

| Model 1 | Five-Factor model: (PJF+PCF), SEFF, JE, PCS, VB | 688.16 | 220 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 251.98 ** |

| Model 2 | Four-Factor model: (PJF+PCF+SEFF), JE, PCS, VB | 892.88 | 224 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.13 | 456.70 ** |

| Model 3 | Three-Factor model: (PJF+PCF+SEFF+JE), PCS, VB | 1029.31 | 227 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.14 | 593.13 ** |

| Model 4 | Two-Factor model: (PJF+PCF+SEFF+JE+PCS),VB | 1310.95 | 229 | 0.66 | 0.62 | 0.16 | 874.77 ** |

| Model 5 | One-Factor model: (PJF+PCF+SEFF+JE+PCS+VB) | 1754.97 | 230 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 1318.79 ** |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gender | 1.40 | 0.49 | ||||||||||

| 2. | Education | 2.80 | 0.81 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| 3. | Job Type | 2.04 | 1.59 | –0.11 | –0.09 | ||||||||

| 4. | Employment Type | 1.14 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.09 | |||||||

| 5. | Person–Job Fit | 4.53 | 1.08 | –0.09 | –0.21 ** | 0.01 | 0.07 | (0.91) | |||||

| 6. | Psychological Contract Fulfillment | 4.57 | 1.13 | –0.07 | –0.05 | –0.02 | –0.06 | 0.40 *** | (0.90) | ||||

| 7. | Self-efficacy | 5.16 | 0.87 | –0.06 | –0.01 | 0.00 | 0.15 * | 0.54 *** | 0.13 | (0.93) | |||

| 8. | Job Engagement | 4.52 | 0.85 | –0.08 | –0.12 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.70 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.67 *** | (0.93) | ||

| 9. | Perceived Coworker Support | 5.38 | 0.94 | 0.08 | –0.04 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.28 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.24 ** | 0.30 *** | (0.91) | |

| 10. | Voice Behavior | 4.76 | 1.20 | –0.10 | 0.07 | –0.12 | –0.02 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.17 * | 0.25 *** | 0.14 | (0.94) |

| Mediator | Subordinate’s Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Engagement | Voice Behavior | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Gender | –0.09 | –0.02 | –0.11 | –0.09 | –0.08 | –0.09 |

| Education | –0.13 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Job Type | 0.00 | 0.00 | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.13 |

| Employment Type | 0.12 | 0.06 | –0.02 | –0.04 | –0.06 | –0.06 |

| Main Effects | ||||||

| Person–Job Fit | 0.70 *** | 0.16 * | –0.05 | |||

| Mediator | ||||||

| Job Engagement | 0.26 *** | 0.29 ** | ||||

| Overall F | 1.68 * | 35.13 *** | 1.44 | 2.07 | 3.91 ** | 3.28 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Change in F | 163.02 *** | 4.51 * | 13.40 *** | 8.86 ** | ||

| Change in R2 | 0.46 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||

| Normal theory tests for indirect effect | ||||||

| Value | SE | z | p | |||

| Sobel | 0.23 | 0.08 | 2.890 | 0.004 | ||

| Bootstrap results for indirect effect | ||||||

| Value | Boot SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | |||

| Effect | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.074 | 0.397 | ||

| Mediator | Subordinate’s Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Engagement | Voice Behavior | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender | –0.09 | –0.07 | –0.11 | –0.11 | –0.09 |

| Education | –0.13 | –0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Job Type | 0.00 | 0.01 | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.13 |

| Employment Type | 0.12 | 0.13 | –0.02 | –0.03 | –0.06 |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Psychological Contract Fulfillment | 0.24 ** | –0.01 | –0.07 | ||

| Mediator | |||||

| Job Engagement | 0.28 *** | ||||

| Overall F | 1.68 | 3.62 ** | 1.44 | 1.14 | 3.42 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.07 |

| Change in F | 11.01 ** | 0.01 | 14.39 *** | ||

| Change in R2 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||

| Normal theory tests for indirect effect | |||||

| Value | SE | z | p | ||

| Sobel | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.450 | 0.014 | |

| Bootstrap results for indirect effect | |||||

| Value | Boot SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | ||

| Effect | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.023 | 0.142 | |

| Mediator | Subordinate’s Outcome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job Engagement | Voice Behavior | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender | –0.09 | –0.04 | –0.11 | –0.09 | –0.08 |

| Education | –0.13 | –0.11 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| Job Type | 0.00 | –0.01 | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.13 |

| Employment Type | 0.12 | 0.01 | –0.02 | –0.05 | –0.06 |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.66 *** | 0.18 * | 0.01 | ||

| Mediator | |||||

| Job Engagement | 0.26 ** | ||||

| Overall F | 1.68 | 31.21 *** | 1.44 | 2.36 * | 3.24 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Change in F | 144.08 *** | 5.88 * | 7.25 ** | ||

| Change in R2 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||

| Normal theory tests for indirect effect | |||||

| Value | SE | z | p | ||

| Sobel | 0.23 | 0.09 | 2.618 | 0.009 | |

| Bootstrap results for indirect effect | |||||

| Value | Boot SE | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI | ||

| Effect | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.070 | 0.429 | |

| Subordinate’s Outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voice Behavior | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender | –0.11 | –0.09 | –0.09 | –0.10 | –0.09 |

| Education | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| Job Type | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.13 | –0.14 | –0.16 * |

| Employment Type | –0.02 | –0.06 | –0.06 | –0.08 | –0.07 |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Person–Job Fit | 0.12 | –0.01 | –0.02 | –0.01 | |

| Psychological Contract Fulfillment | –0.07 | –0.07 | –0.10 | –0.09 | |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| Main Effects | |||||

| Job Engagement (JE) | 0.29 * | 0.26 * | 0.24 * | ||

| Moderator | |||||

| Perceived Coworker Support (PCS) | 0.13 | 0.09 | |||

| Interaction Effects | |||||

| JEa PCSb | –0.17 * | ||||

| Overall F | 1.44 | 1.93 | 2.54 * | 2.58 ** | 2.91 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Change in F | 2.54 | 6.41 * | 2.68 | 5.29 * | |

| Change in R2 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Byun, G. Building a Thriving Organization: The Antecedents of Job Engagement and Their Impact on Voice Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187536

Kim J, Lee S, Byun G. Building a Thriving Organization: The Antecedents of Job Engagement and Their Impact on Voice Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187536

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jinhee, Soojin Lee, and Gukdo Byun. 2020. "Building a Thriving Organization: The Antecedents of Job Engagement and Their Impact on Voice Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187536

APA StyleKim, J., Lee, S., & Byun, G. (2020). Building a Thriving Organization: The Antecedents of Job Engagement and Their Impact on Voice Behavior. Sustainability, 12(18), 7536. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187536