Social Innovation, Societal Change, and the Role of Policies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Developing a Heuristic Model for Analysing Policies and Social Innovation

2.2. Applying the Heuristic Model in Three In-depth Case Studies of Social Innovation in Rural Areas

- The initiative Apprentice Worlds represents a social innovation promoted by a LEADER Local Action Group in a disadvantaged rural area in Austria. LEADER is a European Union structural policy instrument for supporting rural development. The initiative aims at closing the gap between rural youth just about to leave the education system and the local economy desperately seeking junior staff and skilled workers. This case study was conducted in the course of the Austrian research project SILEA (Social Innovation in LEADER 2014–2020: LAG Zeitkultur Oststeirisches Kernland 2020). The SILEA research team analyzed available documents and carried out interviews with eight interlocutors: four current or former project managers, the LAG manager, one participating entrepreneur, one representative from the regional Chamber of Commerce, and one from the State government. Finally, a focus group with representatives from other social innovation initiatives was organized. The comprehensive case study [22] followed a format applied to all the eight in-depth case studies of SILEA, inspired by the innovation biography methodology [23].

- Braemar Community Hydro was promoted by a Community Development Trust in Scotland/UK. This small-scale hydro-power plant is a community-owned enterprise and community benefit society. This case has been studied as a secondary case study in the frame of SIMRA [24] and was not included in the SIMRA cross-case analysis [14]. For the research, a focus group discussion with the chair of the community enterprise, those responsible for the financial and technical development of the hydro power plant, and a project officer (4 persons) and interviews with the core and network actors of the project were conducted (7 persons), following the methodology for the detailed analysis of social innovations developed for the SIMRA project [9,25].

- The Agricultural Development Fund Fenomena (DAFF) was established by the Citizens Association Fenomena. It operates as a business angel in support of integrated, sustainable agriculture in Serbia. This case study has been conducted as a primary source for this article. Three interviews were conducted, one with the project manager of the Fenomena Association, one with the head of a government unit supporting the initiative, and one with the representative of the coalition for the development of the solidarity economy, which is an informal network of organizations that support the development of solidarity entrepreneurship. Parts of the data from these interviews were used in another publication focusing on the analysis of institutional challenges confronting social innovation in Serbia [26].

3. Theoretical Background: Social Innovation and Policies—a Delicate Relationship

3.1. Social Innovation in the Sustainability Debate

3.2. Policies and Political Frameworks

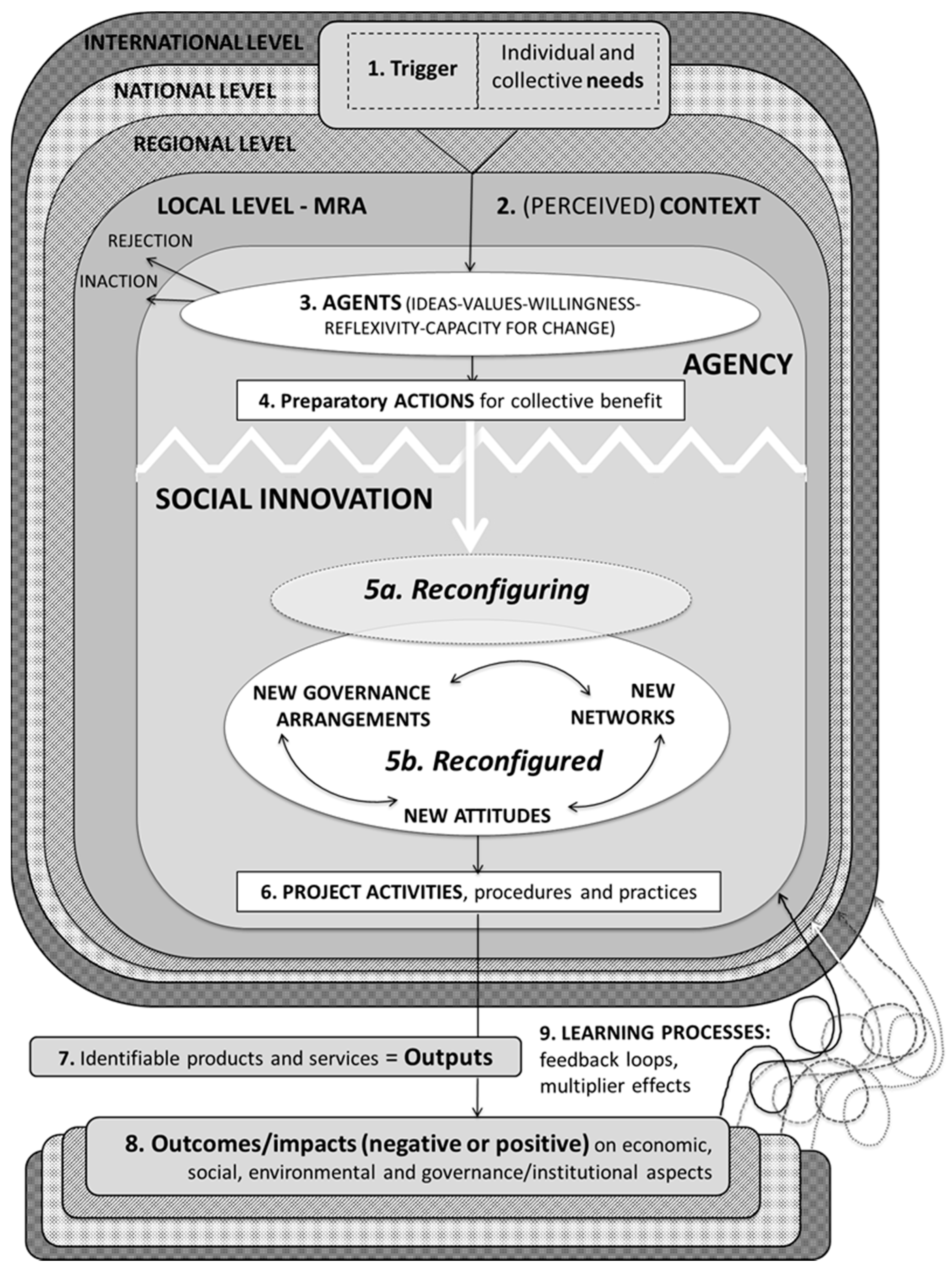

3.3. Structure and Agency: The SIMRA model of Social Innovation

3.4. Institutions, Trust and Governance

3.5. Public Governance and Social Innovation

3.5.1. Factors Hampering Social Innovation

3.5.2. Furthering Factors

4. A Heuristic Model: The Triad of Actors

4.1. A Trusted Core of Key Actors

4.2. Intermediary Support Structures

4.3. The Shadow of Hierarchy

5. A Closer Look on Three Social Innovation Initiatives

5.1. Apprentice Worlds, Promoted by the Local Action Group “Zeitkultur Oststeirisches Kernland” in Styria, Austria

- The initiative emerged at the interface between specific policy fields, in this case education and labor market policies. It literally straddles these two, with remarkable implications on a wider spectrum of policies regarding youth, social inclusion, and the regional economy marked by tradition-rich craft businesses. Inconsistencies and gaps in the institutional fabric at the fringes of policy fields have helped trigger the initiative, but these gaps continue to pose problems when it comes to the question of scaling up and mainstreaming.

- The creative use of diverse funding options from structural (LEADER and INTERREG) and sectoral funding sources (from the State government education department), orchestrated in an uninterrupted row of projects over eight years, would not have been possible without the visionary force and negotiating power of the Local Action Group and its management, based on the independent mandate from bottom-up.

- The LEADER approach allows for a double role of the local partnership: first as a financial enabler and supporter of social innovation, and second as a promoter and spearhead of social innovation. The LAG in its dual role as an innovative core actor and as a prototypical intermediary support structure has spawned this social innovation initiative, but still not achieved the stage of cord clamping the former from the latter. Thus, the LAG is more and more perceived as a main actor in the respective policy fields, to the detriment of its position as a cross-sectoral, cross-thematic, and impartial enabler, which makes it vulnerable to getting tied up with the ups and downs of local politics and jealousies between different stakeholder groups. However, the original intention of the LAG was not to become a major actor in this field. It would rather like to hand over the activities to incumbent operators, but the historically grown delimitation of competences seems to hamper the integration of the reconfigured practice.

- The case provides a vivid example of how institutional frameworks can have both reinforcing and debilitating effects concurrently. On the one hand, the combination of the hands-on approach to job orientation with the integration of asylum seekers was singled out as being exemplary in a nation-wide competition by the national government; on the other hand, the same initiative got shattered by the work ban for asylum seekers, which was put in place by the ensuing government. The result of antithetic political tendencies was not neutrality, but blockade.

- Figure 3 provides some salient features of the triad of actors appearing in the Styrian case example. These are also described in Table 2 in the discussion section where the three cases are compared. The LAG has succeeded in spawning an initiative that meets an urgent societal need that has not been properly met by existing institutional arrangements. What has not been achieved so far is an impact on the institutional frameworks in a way that guarantees the insertion of the innovation without any longer depending on the LAG, which, as an intermediary support structure, understands its role as social entrepreneur to generate local innovation rather than to become a permanent service provider in a specific sector or thematic field.

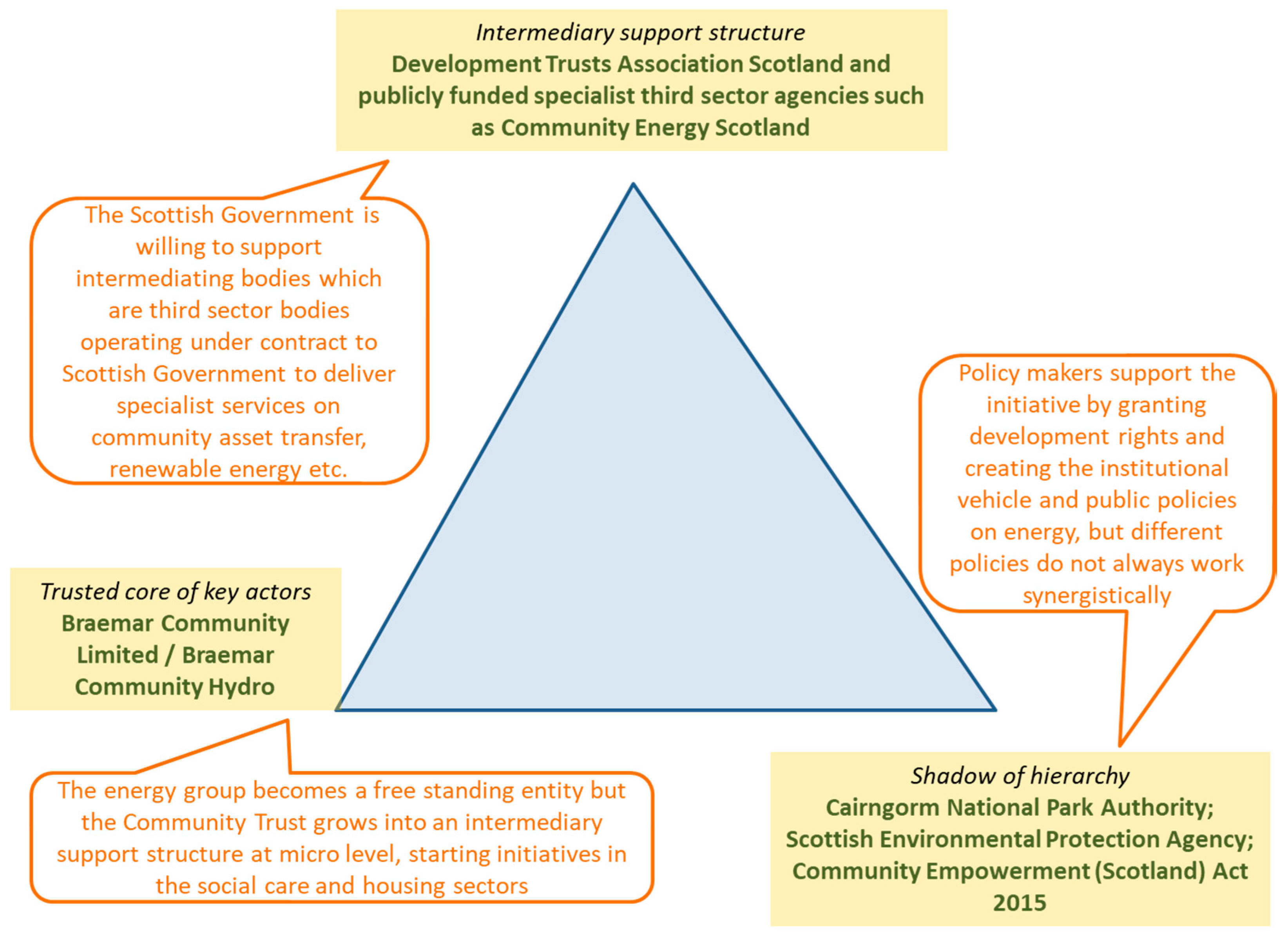

5.2. Braemar Community Hydro in Scotland/UK

- An enabling policy environment is essential in community energy policy, in renewable energy commitments, and in supporting development trusts. The policy is only partially enabling. It still demands a huge community effort to bid into the public and third sector funds that support community-based development.

- Strong social capital in the community and the willingness to engage with policy and a capacity to surmount difficulties are key. The case shows the importance of highly motivated and capable incomers combined with locals to produce solidarity and a capacity to act. Many communities lack these skills, and therefore the social innovation may well not be replicated everywhere.

- A set of challenges to the long-term viability of the community existed that demanded a local rather than a generic public sector response. The existing architecture of housing policy and of social care policy was not working. In the case of the energy project, this was opportunistic engagement, based on a desire to finance community development, breaking the reliance on funds from LEADER or the municipality.

- Figure 4 characterizes the triad of actors for the Scottish case example, and further explanations are included in the comparative Table 2. The Community Trust has come into being and thrives in response to receding public agency, in areas of community interests where individualist approaches provide even less answers. This development is certainly favored by the Scottish constitution and the public provision of intermediary support structures in various sectoral and thematic areas. This publicly driven effort is not always successful, as the rather bureaucratic handling of LEADER shows. However, the burgeoning of similar community initiatives all over Scotland led to the formation of an Association of Community Trusts (DTAS 2020), which enables the single community trusts to bundle forces and to get involved at national level of scale. Further down toward the micro level, the Scottish example shows the fractalness of the triad model, as the Braemar Community Trust is increasingly growing into the role of an intermediary support structure for local initiatives, which are supposed to run independently to the benefit of the people of Braemar.

5.3. Agricultural Development Fund Fenomena in Serbia

- This case shows that there is a high interest from civil society to become active in social issues and to contribute to solving local problems, experimenting new activities and new modes of cooperation with the local population, thus filling the gaps that now exist in the institutional system. However, the weak institutional environment barely provides appropriate political support for social innovation initiatives or enterprises. There is a need for specific policies and programs in recognition of social innovation as a broad concept spanning across and relevant to different sectors.

- The absence of specific supportive policies entails pronounced financial dependencies. Fenomena got support from international funds and is currently grappling with the challenge to secure further funding and to broaden its financial base. There is a need to diversify financial resources for social innovation, with public funds playing a key role in it.

- The triad of actors in the Serbian case example is illustrated in Figure 5 and summarized in Table 2. The weakest part of the triad is the shadow of hierarchy. There is no option for Fenomena to get funded from rural development budgets, but it has access to some funds for social activities from the government unit SIPRU directly attached to the Prime Minister’s office. However, this office lives on support from international donors. For the sake of sustainability, the Association Fenomena created DAFF, a micro-finance instrument by which it supports activities of vulnerable groups in rural areas. As in the Scottish case, the fractalness of the triad model reveals itself to the extent as Fenomena becomes an intermediary support structure for local initiatives.

6. Discussion

6.1. The Benevolent Shadow of Hierarchy

6.2. The Importance of Intermediary Structures

6.3. The Trusted Core of Key Actors

6.4. Bottom-Up and Top-Down

6.5. The Path Toward Long-Term Viability

6.6. The Triad of Actors May be More or Less Balanced

6.7. The Triad is Fractal

6.8. Social Capital and Trust are Depletable Resources

7. Conclusions on the Research Questions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berger, W.F. Innovation als Sozialer Prozess am Beispiel Neo-Endogener Regionalentwicklung in der Europäischen Union. Ph.D. Thesis, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Graz, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, A.; Lester, L. Institutional thickness and institutional effectiveness: Developing regional indices for policy and practice in Australia. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Vision and Trens of Social Innovation in Europe; DG Research and Innovation of the EC: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosdale, L.; Slee, B. Social Innovation: A Must-Have for Marginalised Rural Areas. ARC 2020 Web Resource. 2020. Available online: https://www.arc2020.eu/social-innovation-a-must-have-for-marginalised-rural-areas/ (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- SIMRA—Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas, EU Horizon 2020 Project, GA Nr. 677622. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Ludvig, A.; Rogelja, T.; Asamer-Handler, M.; Weiss, G.; Wilding, M.; Živojinović, I. Governance of Social Innovation in Forestry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kluvankova, T.; Gežik, V.; Špaček, M.; Brnkaláková, S.; Slee, B.; Polman, N.; Valero, D.; Bryce, R.; Alkhaled, S.; Secco, L.; et al. Transdisciplinary Understanding of SI in MRAs. Report D2.2. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Burlando, C.; Da Re, R.; Gatto, P.; Pettenella, D.; Vassilopoulus, A.; Akinsete, E.; Koundouri, P.; Lopolito, A.; et al. Set of Methods to Assess SI Implications at Different Levels: Instructions for WPs 5&6. Report D4.2. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Rogelja, T.; Burlando, C.; Vicentini, K.; Pettenella, D.; Masiero, M.; Miller, D.; Nijnik, M. Towards a method of evaluating social innovation in forest-dependent rural communities: First suggestions from a science-stakeholder collaboration. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 104, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Rogelja, T.; Burlando, C.; Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Živojinović, I.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; et al. Manual on Innovative Methods to Assess SI and its Impacts. Report D4.3. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2019. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V.; Ravazzoli, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Da Re, R.; Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Akinsete, E.; et al. Case Study Protocols and Final Synthetic Description for Each Case Study. Report D5.1. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2018, p. 158. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Marini Govigli, V.; Melnykovych, M.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Ravazzoli, E.; Da Re, R.; Pisani, E.; Secco, L.; Vincentini, K.; Ludvig, A.; et al. Report on Social Innovation Assessment in Each Selected Case Study. Report D5.3. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2019. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Ravazzoli, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Streifeneder, T.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Secco, L.; Górriz-Mafsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V.; Melnykovych, M.; et al. Final Report on Cross-Case Studies Assessment of Social Innovation. Report D5.4. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2020, p. 119. Available online: https://bia.unibz.it/handle/10863/14724 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Weiss, G.; Ludvig, A.; Lukesch, R. Relationships between Policy and Social Innovation. In Final Report on Cross-Case Studies Assessment of Social Innovation; Ravazzoli, E., Dalla Torre, C., Streifeneder, T., Pisani, E., Da Re, R., Vicentini, K., Secco, L., Górriz-Mifsud, E., Marini Govigli, V., Melnykovych, M., et al., Eds.; Report D5.4. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA); 2020; pp. 69–84. Available online: https://bia.unibz.it/handle/10863/14724 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Živojinović, I.; Nijnik, M.; Miller, D.; Barlagne, C.; Perlik, M.; Hermann, P.; Egger, T.; Dalla Torre, C.; et al. Political Framework Conditions, Policies and Instruments for SIs in Rural Areas. Report D6.1. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Sarkki, S.; Nijnik, M.; Živojinović, I. Mapping European and forest related policies supporting social innovation for rural settings. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 97, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Živojinović, I.; Nijnik, M.; Miller, D.; Barlagne, C.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.; Jack, S.; Al Khaled, S.; Polman, N.; et al. Policy Implications for Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas. Report D6.2. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA). 2018. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Slee, B. Social innovation in community energy in Scotland: Institutional form and sustainability outcomes. Glob. Transit. 2020, 2, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B.; Mosdale, L. How policy can help bring about social innovation in rural areas. In Policy Brief; 2020; p. 16. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2020-02-03-Policy-brief_Slee-Mosdale_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Lukesch, R.; Dalla Torre, C.; Valero, D.; Ravazzoli, E. Conclusions. In Final Report on Cross-Case Studies Assessment of Social Innovation; Ravazzoli, E., Dalla Torre, C., Streifeneder, T., Pisani, E., Da Re, R., Vicentini, K., Secco, L., Górriz-Mifsud, E., Marini Govigli, V., Melnykovych, M., et al., Eds.; Report D5.4. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA); 2019; pp. 98–103. Available online: https://bia.unibz.it/handle/10863/14724 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Lukesch, R.; Ecker, B.; Fidlschuster, L.; Fischer, M.; Gassler, H.; Mair, S.; Philipp, S.; Said, N. Analyse der Potenziale Sozialer Innovation im Rahmen von LEADER 2014–2020; ÖAR and ZSI: Wien, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Butzin, A.; Widmaier, B. Exploring Knowledge Dynamics through Innovation Biographies. Reg. Stud. 2016, 50, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B. Analytical-Informational Case Studies (Case Study Type B/C): Braemar and Huntly Community Energy Projects; Report 5.4q. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Da Re, R.; Pisani, E.; Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V. Compilation of Tools for Data Collection for SIMRA Pioneer and Regular Case Studies. Report 5.1, Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA). 2018. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/index.php/deliverables/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Živojinović, I.; Ludvig, A.; Hogl, K. Social Innovation to Sustain Rural Communities: Overcoming Institutional Challenges in Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polanyi, K. The Great Transformation; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; (original publishing year: 1944). [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Central Problems in Social Theory; MacMillan Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P. Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Practice and Principles; Harper Business (Reprint): New York, NY, USA, 2006; (original publishing year: 1985). [Google Scholar]

- Polman, N.; Slee, B.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn, M.; Nijnik, M.; Gezik, V.; Soma, K. Classification of Social Innovations for Marginalized Rural Areas. Report D2.1. SIMRA. 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/D2.1-Classification-of-SI-for-MRAs-in-the-target-region.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Millard, J. How Social Innovation Underpins Sustainable Development. In Atlas of Social Innovation; TU Dortmund University: Dortmund, Germany, 2017; pp. 40–43. Available online: https://www.socialinnovationatlas.net/fileadmin/PDF/einzeln/01_SI-Landscape_Global_Trends/01_07_How-SI-Underpins-Sustainable-Development_Millard.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Nichol, M. Social vs. Societal, Web Resource (Daily Writing Tips). 2012. Available online: https://www.dailywritingtips.com/social-vs-societal/ (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Grimm, R.; Fox, C.; Baines, S.; Albertson, K. Social innovation, an answer to contemporary challenges? Locating the concept in theory and practice. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 26, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans-Videc, M.-L.; Rist, R.C.; Vedung, E. Carrots, Sticks & Sermons: Policy Instruments and Their Evaluation; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity; E.P. Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.; Varela, F. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding; Shambala: Boston, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Stengers, I. Order out of Chaos: Man’s New Dialogue with Nature; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, S.P. Political Order in Changing Societies; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Penven, A. Recognition and Institutionalisation of Social Innovations in the Field of Social Policy. Innovations 2015, 3, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Walker, J. Trust and Reciprocity. Interdisciplinary Lessons from Experimental Research; Russell Sage Foundation Series on Trust; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume VI. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziale Systeme: Grundriss Einer Allgemeinen Theorie; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. The Prosperous Community. Am. Prospect 1993, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, N. On ne peut pas institutionnaliser l’innovation. In L’innovation Sociale. Émergence et Effets sur la Transformation des Sociétés; Klein, J.L., Harrison, D., Eds.; Presses de l’Université de Québec: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2007; pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Heiland, K. Kontrollierter Kontrollverlust. Jazz und Psychoanalyse; Psychosozial-Verlag: Giessen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. The dynamics of transitions: A socio-technical perspective. In Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Grin, J., Rotmans, J., Schot, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lukesch, R. Policy Recommendations from the SIMRA Project. In Proceedings of the SIMRA Conference: Social Innovators in Rural Areas, Bruxelles, Belgium, 19 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Domanski, D.; Kaletka, C. Lokale Ökosysteme sozialer Innovation verstehen und gestalten. In Soziale Innovationen Lokal Gestalten; Franz, H.W., Kaletka, C., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J. System Failure. In Why Governments Must Learn to Think Differently; DEMOS: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Isaksen, A.; Trippl, M. Innovation in space. The mosaic of regional development patterns. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2017, 33, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Why Nations Fail; Profile Books: Croydon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. The Narrow Corridor; Pengiun Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G.; Albury, D. Innovation in the Public Sector; Strategy Unit, UK Cabinet Office, UK Government: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Bauer, A.; Weiss, G. Policy Integration and Coordination: Theoretical, Methodical and Conceptual Approach. In Policy Integration and Coordination: The Case of Innovation and the Forest Sector in Europe, 15; Rametsteiner, E., Weiss, G., Ollonqvist, P., Slee, B., Eds.; OPOCE: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R.; Berger, G. Horizontal policy integration: Concepts, administrative barriers and selected practices. In Nachhaltigkeit regieren: Eine Bilanz zu Governance-Prinzipien und -Praktiken [Governing Sustainability: Taking Stock of Governance Principles and Practices]; Steurer, R., Trattnigg, R., Eds.; Oekom: München, Germany, 2010; pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. Ready or not? Taking Innovation in the Public Sector Seriously; NESTA Provocation 03 April 2007; NESTA: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation—The Young Foundation; NESTA: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation? Am. J. Eval. 1998, 19, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlagne, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Hewitt, R.; Nijnik, M. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Lochcarron Community Development Company—Strathcarron, Scotland, UK (led by HUTTON); Report 5.4j. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Fernández-Blanco, C.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V.; Prokofieva, I. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Forest Fire Volunteer Groups—Catalonia, Spain (CTFC); Report 5.4a. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dalla Torre, C.; Gramm, V.; Lollini, M.; Ravazzoli, E. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Learning, Growing, Living with Women Farmers—South Tyrol, Italy (EURAC); Report 5.4d. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Dargan, L.; Shucksmith, M. LEADER and Innovation. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B. A personal journey through the policy maze: Alford and District Men’s Shed. In Proceedings of the SIMRA SITT meeting in Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK, 14–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnykovych, M.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.; Polman, N. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Care Farm Pitteperk—The Netherlands (led by DLO); Report 5.4c. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnykovych, M.; Kozova, M.; Spacek, M.; Kluvankova, T. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Revitalising Plans for Vlkolinec—Slovakia (Led by IFE SAS/CETIP); Report 5.4k. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- GIZ. Cooperation Management for Practitioners. Managing Social Change with Capacity WORKS; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani, E.; Franceschetti, G.; Secco, L.; Christoforou, A. (Eds.) Social Capital and Local Development. From Theory to Empirics; Palgrave Macmillan Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Esslinger, E.; Schlechtriemen, T.; Schweitzer, D.; Zons, A. Die Figur des Dritten. Ein kulturwissenschaftliches Paradigma; Suhrkamp/Insel: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rajan, R. The Third Pillar. How Markets and the State Leave the Community Behind; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Akinsete, E. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) A Box of Sea—Lesvos and Leros, Greece (ICRE8); Report 5.4i. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnykovych, M.; Labidi, A.; Chorti, H.; Bengoumi, M. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) Supporting Dairy Producers Organisations through a Public-Private Partnership Programme—Tunisia (led by FAOSNE); Report 5.4h. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Lopolito, A.; Baselice, A.; Prosperi, M. Analytical Case Studies (Case Study Type A) VAZAPP’—Apulia, Italy (UNIFG); Report 5.4g. Internal project report. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvig, A.; Corradini, G.; Asamer-Handler, M.; Pettenella, D.; Verdejo, V.; Martínez, S.; Weiss, G. The practice of innovation: The role of institutions in support of Non-Wood Forest Products. BioProducts Bus. 2016, 6, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Ludvig, A.; Živojinović, I.; Asamer-Handler, M.; Huber, P. Non-timber innovations: How to innovate in side-activities of forestry—Case Study Styria, Austria. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2017, 134, 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Churchman, C.W. Wicked Problems. Manag. Sci. 1967, 14, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinčić, D.A. Innovations in Culture and Development: The Culturinno Effect in Public Policy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K. Innovations for conservation and development. Geogr. J. 2002, 168, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharpf, F.W. Games Real Actors Can Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Servillo, L. Tailored polities in the shadow of the state’s hierarchy. The CLLD implementation and a future research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 678–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butkeviciene, E. Social innovation in rural communities: Methodological framework and empirical evidence. Soc. Sci. 2009, 1, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hasse, R.; Krücken, G. Neo-institutionalistische Theorie. In Handbuch Soziologische Theorien; Kneer, G., Schroer, M., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.W.; Khoury, T.A.; Hitt, M.A. The influence of formal and informal institutional voids on entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinović, N. Social Enterprise Ecosystem in Serbia. In Social Enterprise Ecosystems in Croatia and the Western Balkans; Etchart, N., Varaga, A., Eds.; A Mapping Study of Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia, Chapter 13; NESsT: San Leandro, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 191–223. Available online: http://connecting-youth.org/publications/publikim19.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- BTI. Serbia Country Report; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.bti-project.org/en/reports/country-dashboard-SRB.html (accessed on 23 July 2020).

| Case Study | Promoter | Location | Characterization of the Social Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apprentice Worlds | LAG Zeitkultur Oststeirisches Kernland, a public–private partnership according to LEADER | Austria (Steiermark) | Local partnership (Local Action Group according to the LEADER approach) acting as a social entrepreneur in the career orientation of school-leavers. |

| Braemar Community Hydro | Braemar Community Limited, a Local Development Trust | UK (Scotland) | Local renewable energy project incubated by a community development enterprise. |

| Agricultural Development Fund Fenomena | Fenomena Assocation, a non-governmental association. | Serbia (Kraljevo area) | Revolving fund run by a civic association acting as a business angel. |

| Triad Elements | Triad Features | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (Apprentice Worlds) | UK/Scotland (Braemar Community Trust and Hydro) | Serbia (Fenomena Association) | ||

| The nodes | Trusted core of key actors | Strong: Enduring management of more than ten different projects under the strategic guidance of the LAG management. Different projects have been seamlessly customized to promote the initiative. | Strong: Braemar Community Limited with Braemar Community Hydro as the economic mainstay. Broad, locally anchored ownership with a high potential for internal diversification. | Strong: Persevering dedication and social commitment of core actors. |

| Intermediary support structure | Strong: Over the years, Apprentice Worlds have been a flagship initiative of the LAG with strong backing by the chairman and active leadership by the LAG manager. The LAG not only provided the appropriate structure for funding, but also knowledge transfer and regional, national, and European networking. | Strong and two-pronged: The Scottish Development Trusts Association represents the interests of a large number of similar initiatives at the national scale of decision making, whereas top-down support is effectively delivered by sectoral state agencies. | Intermittent and delicate in terms of political contingencies: Full reliance on international donors and development projects. | |

| Shadow of hierarchy | Obtainable, but dispersed: There is widespread recognition among the regional and national polity, but not sufficient political will to institutionalize the initiative due to the perseverance of sectoral divisions and role attributions. | Strong, but still improvable: The constitution of the nation state provides the matrix for a broad political consensus on community empowerment. Some friction losses through sectoral silos and a weak territorial cross-sectoral coordination (LEADER) dominated by municipal interests. | Weak: Encouragement by an internationally funded unit at the Prime Minister’s office. | |

| Edges linking the nodes | Core actors <–> support structure | The key actors (Apprentice Worlds) still fully depend on the intermediary support structure (LAG Zeitkultur). Independent ownership would be necessary to make the initiative sustainable. | Strong ties: Technical top-down support complemented by bottom-up representation of interests. | Strong ties based on longstanding experience in international fund raising and project acquisition, but overall dependency on project cycles. |

| Support structure <–> shadow of hierarchy | It has cost the LAG some time to become acknowledged as a social entrepreneur in this field, but it has succeeded in it. This has, however, not led to regime change, which would allow the Apprentice Worlds to get mainstreamed. | Strong and consistent: The structures are built upon the consensus on decentralization and community empowerment. Sector silos and municipal power claims constitute challenges. | Strong link between the two nodes through international donors, with only weak embedding in the Serbian domestic policy context. | |

| Shadow of hierarchy <–> core actors | There is an ongoing dialogue between project promoters and local and regional polity, fostered by the LAG, which, as a well-established public–private partnership, provides the institutional space for continuous concertation across all sectors. | The local initiative, like many similar ones in Scotland, responded to an open invitation, which was based on the political consensus on decentralization and community empowerment. | There is no political provision (funding, advice) for social innovation support, and core actors operate under conditions of permanent uncertainty in an overall unstable political–institutional environment. | |

| General appreciation |

|

|

| |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lukesch, R.; Ludvig, A.; Slee, B.; Weiss, G.; Živojinović, I. Social Innovation, Societal Change, and the Role of Policies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187407

Lukesch R, Ludvig A, Slee B, Weiss G, Živojinović I. Social Innovation, Societal Change, and the Role of Policies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187407

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukesch, Robert, Alice Ludvig, Bill Slee, Gerhard Weiss, and Ivana Živojinović. 2020. "Social Innovation, Societal Change, and the Role of Policies" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187407

APA StyleLukesch, R., Ludvig, A., Slee, B., Weiss, G., & Živojinović, I. (2020). Social Innovation, Societal Change, and the Role of Policies. Sustainability, 12(18), 7407. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187407