COVID-19 and Disruption in Management and Education Academics: Bibliometric Mapping and Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Synopsis of Literature

3. Methodology

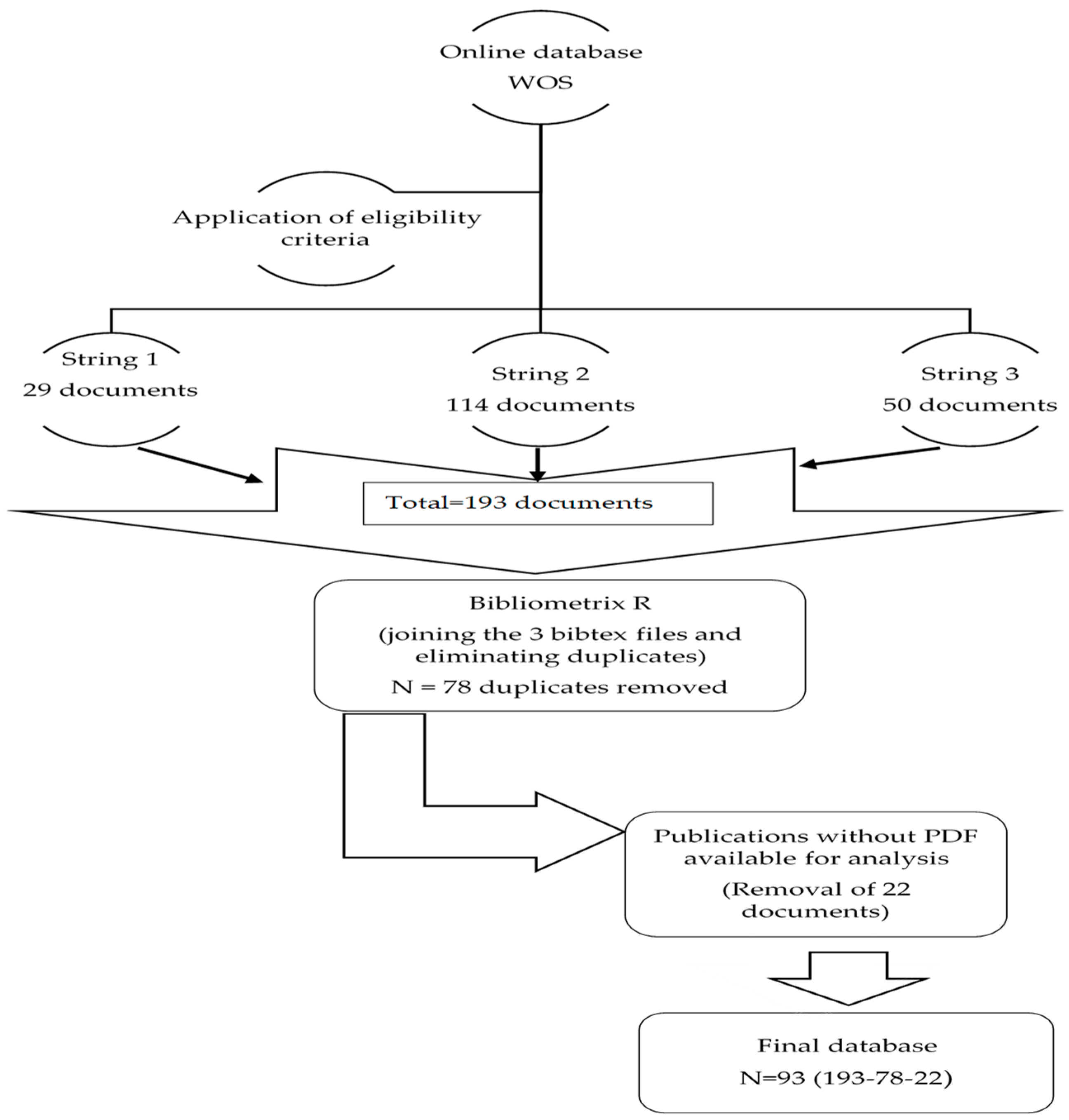

3.1. Data Collection and Eligibility Criteria

3.2. Methodological Procedures

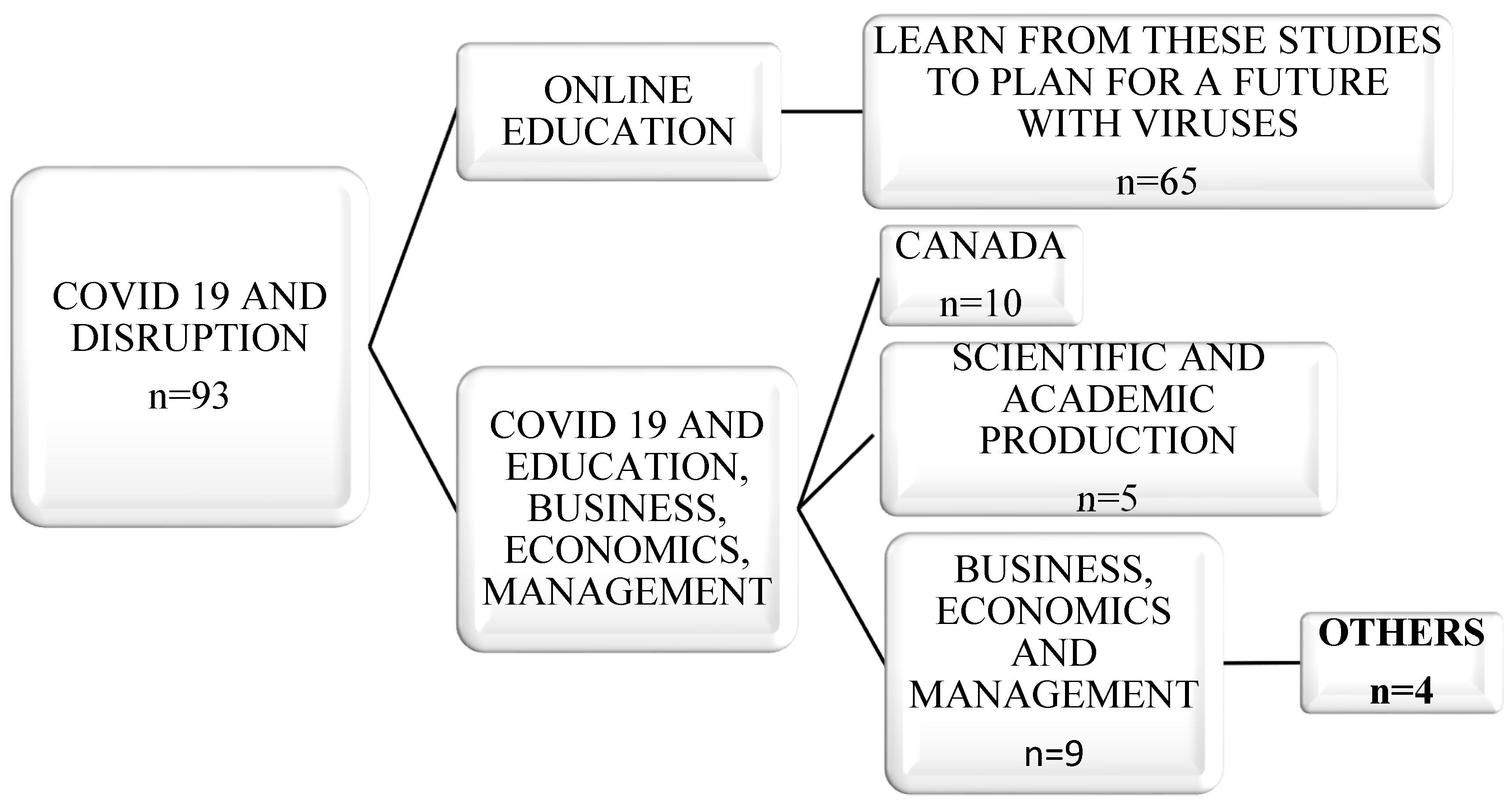

4. Mapping and Qualitative Analysis

5. Content Analysis

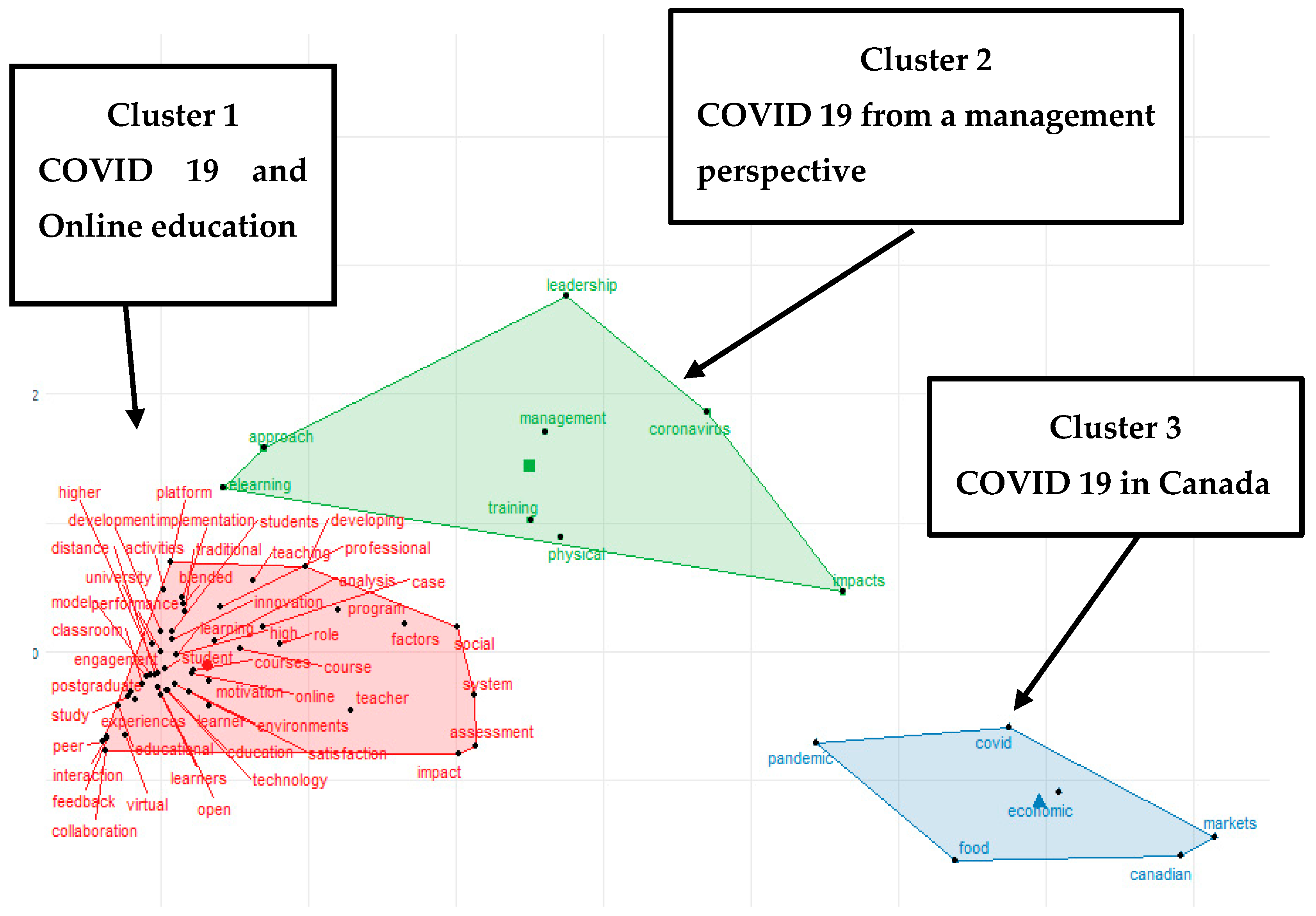

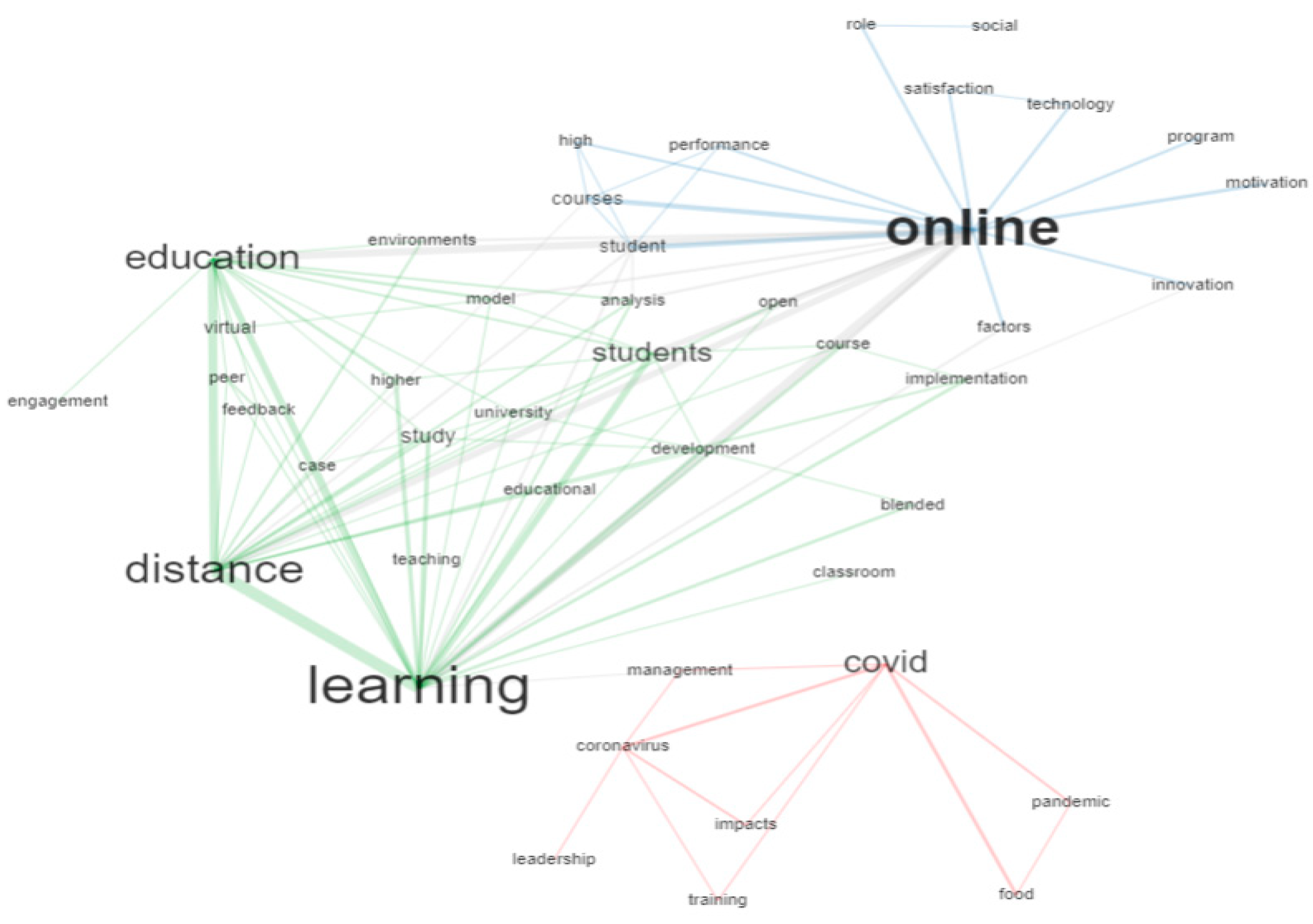

6. Bibliometric Analysis

7. Conclusions and Contributions

8. Limitations and Future Avenues of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors/Year | Type of Study | Content Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Fernandes, De Oliveira Lima, Da Silva, Sales, & De Orange [109] | Empirical | Investigating why health professionals should have management competences. These competences are important in providing a service of excellence. Therefore, they implemented a specialized course in management for oncologists, through “blended learning”. The results obtained show these professionals’ satisfaction with acquiring these additional competences, which can change their behavior regarding improved health care and its costs. |

| Lee [110] | Conceptual | Critical review of open educational practices (OEP). Explaining that OEP courses should be opened for the most disadvantaged students. |

| Ortagus, Yang, Voorhees, & Riggs [111] | Empirical | They aimed to determine whether the effect of the requested budgets has anything to do with the total number of students online at community universities. Concluding that the financial structure hinders that relation, although the statistical relationship between the number of students and costs is not significant. |

| Choi & Choi [112] | Empirical | Detail the benefits and challenges for teachers in online international collaboration in courses in Korea and China, based on students’ feedback and lecturers’ reflections. Considered that intercultural competences were improved and that lecturers face joint challenges (e.g., scheduling classes, aligning course content, language) |

| Saltz & Heckman [113] | Empirical | Whether the use of videos in online courses can increase performance, as long as they are improved, specifically by using the Structured Paired Activity (SPA) tool. Concluding that the introduction of SPA stimulates performance, since this tool raises student involvement and the effectiveness of the online teaching process. |

| Ruipérez-Valiente, Halawa, Slama, & Reich [114] | Empirical | Exploring the differences in students’ behavior and preferences in using the platforms of Open EDX Platform and regional Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) in Jordan. Concluding that the regional MOOC is more attractive, because the courses pay special attention to students’ interests and their learning needs |

| Matthews & Kotzee [115] | Empirical | Part-time study in the UK is in decline, and the cause of this was researched. Obtained evidence that fees and the increase in online education platforms were and will continue to be reasons for that decline. |

| Mapp & Boutté-Queen [116] | Empirical | Analyzing baccalaureate course programmes in social work in the USA and their lecturers. Concluded that most lecturers do not have training in teaching online, which leads to the stressors of accreditation, time and monetary matters being called into question. |

| Alanazi et al. [117] | Empirical | Assessment of the perceived performance of students on online post-graduate courses. Considered that this has the predictors of the value of the task and the quality of the content taught, with the relation between students and technology having no significant effects on performance. |

| Shahzad et al. [118] | Empirical | Analyzing MOOC based on the technological-organisational-environmental approach. Finding significant relations between the technological and organisational constructs, as well as attitudes towards the use of cloud computing. On the contrary, the environmental construct did not show any relations. |

| Zheng et al. [60] | Empirical | Investigating the student-teacher relationship in online teaching. The results obtained showed that students achieved better results if they logged in more frequently, remaining longer online; while for teachers, their influence varies according to their level of qualification. |

| Littenberg-Tobias, Valiente, & Reich [119] | Empirical | Exploring the relation between monetary cost and learning behavior in MOOC. Finding that not only the financial aspect motivates students to complete the course and attend classes, with the type of information and communication technology and programme contents having a relevant effect on completion. |

| Forde & Gallagher [120] | Empirical | Aiming to understand why continuous training in the online model is important for nurses and what the difficulties are. Proposing that nurses are concerned about their capacity to respond to the standards defined by online courses. Despite having experienced support from other actors they are still concerned about time management. |

| Danka [62] | Conceptual and exploratory | Investigate the conclusion rates of MOOC. Despite massive enrolments on these courses, completion rates are low, possibly due to the lack of an appropriate method to assess the evolution of learning and motivational resources. Therefore, the proposal of a new theoretical framework to solve resource allocation in MOOC, where a weak student-teacher relationship persists. |

| Anderson & Cuttler [121] | Empirical | Studying the adoption of e-books (open textbook). Finding that adoption of this type of book is less favoured than traditional books, with the cost factor having impacts on this transition. |

| Elizondo-Garcia & Gallardo [122] | Empirical | Identifying the perceptions of students on MOOC courses about the student/teacher interaction and feedback. The empirical evidence obtained showed that most participants are willing to interact with their fellow students and participate in feedback activities. They also demonstrated that peer-assessment is more appropriate for that feedback. |

| Harper et al. [57] | Conceptual | Analyzing digitalization of educational services from the perspective of innovation and entrepreneurship. Concluding that online courses are complex and that they are a new typology of innovation and entrepreneurship, due to implying the creation of new designs and being included in social and institutional structures that co-evolve with technological changes. |

| Wilhelm-Chapin & Koszalka [100] | Empirical | Assessing students’ interactions with online course content in higher education and their involvement, through Generative Learning Theory. Highlighting that this topic needs continuous study of the connections between resources, interaction and student involvement. They also mentioned that students would like to have access to didactic material before online classes, do more exercises and reflect on cases. |

| Williams, Martinasek, Carone, & Sanders [123] | Empirical | Examining the differences in perceptions between F2F and online teaching in physical education. The main deduction was that online teaching brings benefits for students also at the personal level, these being important for them. |

| Sinacori [124] | Empirical | Analyzing the experiences of nursing teachers in the transition from the classroom to an online environment. Through those experiences, it was claimed these teachers need to have their training enhanced for this transition, given the need to manage time, students’ expectations and the pedagogical benefits of those courses. |

| Kauppi, Muukkonen, Suorsa, & Takala [95] | Exploratory | Based on the feeling of a lack of human contact in online teaching, exploring the complaints/reactions of those involved. Developing a pedagogical design of a course, through the benefits and challenges in reaching the desired learning in online teaching, emphasizing the combination of joint creation of knowledge, in a virtual, flexible environment involving a multi-disciplinary group. |

| Gay & Betts [125] | Empirical | Simulation of a real E-Meeting task in a firm on an online course. The results revealed that this task can pro-actively increase student involvement and retention in online courses, and so the simulation was a success. Moreover, it created opportunities and gave students new competences demanded by employers (e.g., problem-solving, teamwork, communication, leadership, time management). |

| Roman et al. [106] | Empirical | Studying ways of making online learning effective. Claiming this is possible by adopting appropriate educational instructional and technological strategies, but there are some barriers to implementation. Consequently proposing an empirically tested tool to achieve that effectiveness, which is a mediator of students’ motivation, cognition and behavior. |

| Park & Kim [96] | Empirical | Studying the possibility of creating a human presence in online teaching. Found it is challenging to promote interactions between all actors in online teaching in the same way as in face-to-face teaching. However, the inter-activity of communication tools can create a social presence and the feeling of student satisfaction in online learning, with the effects being significant and moderated by gender. |

| Yilmaz & Banyard [58] | SLR | Analyzing trends of student involvement in distance learning. The contributions of this SLR concerned the existence of efforts to encourage that involvement to take place, despite previous research having concentrated on the institutional design and educational technology, leading to a shortage of studies in the area of education systems and distance education theories. In addition, it is necessary to pay attention to properties of the media, students’ characteristics, the teaching method, course design and content, innovative techniques and lecturers’ competences, besides Chickering and Gamson’s principles of good practices which are so important in this student involvement. |

| Lee, Chang, & Bryan [126] | Empirical | Studying the factors affecting the success of Ph.D. students in leadership on online courses. Concluding that relational and technological factors predict independently and interactively these students’ successful learning, with it being essential to build a relation between both parties. |

| Skelcher, Yang, Trespalacios, & Snelson [94] | Empirical | Obtaining proof that online teaching affects the feeling of community in relation to the institution. From analysis of an online post-graduate course, they confirmed that feeling is very low and should be improved. As there is a proliferation of courses online, institutions should improve their forms of support. |

| Peacock, Cowan, Irvine, & Williams [93] | Empirical | Exploring the feeling of belonging in online courses. Emphasizing that this type of teaching must give value to interaction, commitment, support and a learning culture between both parties, since these factors influence the feeling of belonging and ensure the existence of opportunities for interaction between colleagues and groups. |

| Ahmed, Khan, Khan, & Mujtaba [127] | Empirical | Studying the importance of social capital and psychological factors of well-being in e-learning systems. Sustained by perceived social support and the use of the media as a moderator, they concluded that in online courses it is important to diagnose and prevent isolation, use software that stimulates social connection, to encourage personal blogs with students and arrange more face-to-face meetings. |

| Yavuzalp & Bahçivan [128] | Empirical | Studying the self-efficacy of university students on online courses. Demonstrating that students’ perceptions of this construct regarding online learning are not affected by gender and type of school. However, several psychological variables should be assessed simultaneously. In addition, the relations between the variables and demographic factors can be defined, and the factors affecting students’ success and satisfaction can be revealed. Conjugating factors in this way facilitates universities’ interventions aiming for students’ success in an online learning environment. |

| Mubarak, Cao, & Zhang [108] | Empirical | Studying low completion rates for online courses. As this is a worrying topic, they built a predictive model to forecast students at risk of dropping out, with the accuracy of that forecast rate depending on the data on students’ behavior. However, these data will only be obtained on courses where there is student involvement in the learning process. |

| Rajagopal et al. [61] | Empirical | Studying open virtual mobility in education. Concluding that on the online courses provided, virtual mobility and open education are variables affecting their quality, resulting in students’ acquisition of new competences, such as autonomy, interaction, collaboration, an open mind and others. |

| Stuij et al. [129] | Empirical | Exploring the training and development of communication competences among oncologists. In this area, online training provides these professionals with benefits, as it is essential they know how to communicate. In addition, this type of training allows accessible forms of learning, in a safe, personalized environment, especially using software that can simulate a conversation with users (Chatbot) rather than e-learning. |

| Sedra [130] | Conceptual | Presentation of a tool to help designers produce educational content, based on the Competency-Based Approach (CBA), which allows incorporation of the desired order of competences of distance learning and interaction, according to an orchestrated plan. |

| Lengyel [104] | Exploratory | Exploring the application of games in teaching accountancy on online courses. In these courses, learning is based on games linked to e-learning and experimental learning, which originated a greater number of active students from one semester to another, given the increasing popularity of gamification. |

| García-Peñalvo [131] | Conceptual | Development of a model of reference for universities with F2F classes to adapt to distance learning, including its structures. |

| Lam & Dongol [103] | Conceptual | One of the important questions with online teaching platforms is the transparency of assessment and the personalization of curricula. Proposal of a theoretical platform that can increase students and lecturers’ trust in universities’ online services, regarding assessment procedures and others. |

| Herodotou et al. [54] | Empirical | Examining the adoption of Predictive Learning Analytics (PLA) in online higher education courses. Concluding that adoption includes lecturers’ commitment and involvement, creating evidence, dissemination and digital literacy. |

| Dwyer & Walsh [53] | Empirical | Exploring distance learning in adults. Highlighting the importance of critical thinking and that e-learning is important for these individuals. |

| Shonfeld & Magen-Nagar [132] | Empirical | Assessing students’ intrinsic motivations in collaborative programmes online. Concluding that motivation is affected by students’ level of satisfaction, which influences their attitudes to technology. Also finding that students begin to enjoy using advanced technology and gain self-confidence, which diminishes technological anxiety regarding online courses. |

| Hilliard, Kear, Donelan, & Heaney [92] | Empirical | Studying students’ anxiety regarding online courses. Finding this is caused by students having to trust in strangers, being afraid of having a negative evaluation and concern about non-active group members. This anxiety diminishes with decreasing uncertainty. |

| Schreiber & Jansz [63] | Empirical | Studying the importance of feedback in distance learning. Concluding that the interaction provided through feedback increased the dialogue between students and lecturers, which reduced the transactional distance. |

| Martin [133] | Empirical | Analysis of distance learning of languages in higher education. Concluding that distance learning of languages benefits from including training directed towards the pronunciation of that language and helps to obtain better performance. |

| Vershitskaya, Mikhaylova, Gilmanshina, Dorozhkin, & Epaneshnikov [134] | Empirical | Assessment of students’ readiness for e-learning, in a management university. Considering that the implementation of e-learning, based on students and lecturers’ perspectives and on existing problems with information technology, failed due to extremely poor marketing strategies and technical support. |

| Andoh, Appiah, & Agyei [135] | Empirical | Assessing students’ satisfaction with distance learning. Students’ satisfaction with this teaching does not depend on age, gender or course content, but is closely related to the location of the study centre and the semester in question. These students were also impressed by the support they were given. |

| Said [136] | Empiricaland descriptive | Determining educational applications and their characteristics, followed by grouping them by category. This description allowed assessment of the performance of these applications regarding students’ use and competences. |

| Kayser & Merz [59] | Empirical | Identifying the various types of student communication in distance learning. Obtaining empirical evidence of 3 types of communication among students: powerful communicators, regular communicators and “lone wolves”. |

| Ramlatchan & Watson [137] | Empirical | The effect of multimedia elements used by lecturers in online courses and their credibility and immediacy among students. Emphasizing that there can be a balance in these students’ perceptions, if the teaching they receive is a mix of online presentations, videos and seeing the lecturer, and if the presentations are good this can create an atmosphere of involvement. |

| Joiner, Rees, Levett, Sitnikova, & Townsend [138] | Empirical | Exploring the effectiveness of online learning by professionals throughout their life. Through elaborating a comparative study of teaching pedagogies regarding their effectiveness for critical thought in online work, they argued that forums are more effective than direct exchange of this critical sense. |

| Duran [99] | Empirical | Study students’ silence in distance learning, through the phenomenological approach. Concluding that students’ silence can have various facets: on purpose; absorption of students’ silence; silence used as demarcation; experiencing silence; use of deliberate, complex strategies when participating; hearing in a trusting community. This means this phenomenon has implications for all actors in distance learning. |

| Zimmerman [105] | Empirical | Study of how to create knowledge-exchange activities in distance learning. The use of recorded conversations and reflections to help distance learning encouraged interactions and critical dialogue among participants, where the language was important for that different form of learning. |

| Krasnova & Shurygin [101] | Empirical | Assessing the competences required of lecturers to teach online. Highlighting the technological competences required of lecturers, despite finding a tendency for the use of information and communication technology in education to facilitate learning, whatever the age of users. |

| Villalpando et al. [139] | Exploratory and descriptive | Comparing the motivation statistics of mathematics students involved in mixed teaching systems - F2F and F2F +e-learning - . Demonstrating that F2F students had better performance in interest, perception and self-efficacy, while those in the mixed system highlighted the financial cost associated with the choice of teaching type. |

| Kilinc, Yazici, Gunsoy, & Gunsoy [107] | Empirical | Study of distance learning in Turkey. Distance learning has had positive effects in Turkey regarding levels of employment (before and after), levels of income and socio-economic well-being. |

| Faisal & Kisman [140] | Empirical | Exploring the effects of using Moodle in distance learning. The empirical evidence indicates that learning through an educational system at a distance can simplify and accelerate work, and allow more accurate and efficient work, due to this platform being interactive and easy to use. |

| Lee, Lim, & Lai [102] | Empirical | Aim to examine teacher training in advanced training at a distance. These programmes last 4 years, with online classes at the weekend and 5 face-to-face meetings. By assessing the performance of these teachers’ practical competences, they argued that they still needed more training to be innovative in teaching and that their cognitive taxonomy has to be emphasized. |

| Jones, Lotz, & Holden [141] | Empirical | Application of Virtual Design Studios (VDS) during a complete higher education course (3 years) and with all its students, integrated in distance learning, to assess the behavior of these students. Concluding that VDS can support learning and social interaction, leading to positive experiences and results for students, although the correlation between VDS and students’ success is higher in the initial stages. |

| Kuznetcova, Lin, & Glassman [97] | Empirical | Questioning the importance of lecturers’ presence in online teaching. This presence has been considered crucial to motivate students, although the use of virtual environments, with multiple users simultaneously, may alter this argument. The results showed that the presence of teachers encourages students’ independence and interactivity. |

| Laurie, Kim, José, & Rob [142] | SLR | Systematization of the literature on the predictors of completing online higher education. Identifying that study strategies, academic self-efficacy, objectives, intentions, institutional or university adjustments, employment, the support network and the student-teacher interaction are predictors of the completion rate of that teaching. Coaching, corrective teaching and peer orientation are promising constructs with a view to solving this problem of course completion. |

| Prasandy, Nurlaila, Titan, & Lena [143] | Conceptual | The differences in teaching students with hearing difficulties. They argued that it is important to find innovative teaching models directed to these students, and so implemented a data and text mining application which produced a 90% improvement in their performance. |

| Yun & Park [98] | Empirical | Studying students’ motivation in higher education, both face-to-face and online. Concluding that improved interest and environmental control are significantly associated with behavioral involvement and that this improvement, orientation by objectives and the behavioral effort are also significantly associated with emotional and cognitive involvement, moderated by students’ academic level. |

| Corsby & Bryant [144] | Empirical | Studying the effects of distance learning in Ph.D. programmes. The results showed the failings of interaction when using technology in distance learning, such as the quality of the technology, familiarity in the classroom, the tutor’s help and the user’s isolation. |

| Amin, Piaralal, bin Daud, & Mohamed [145] | Transversal investigation of the relations between the dimensions of justice, university image and users’ satisfaction with services. The results revealed a significant relation between the dimensions of justice and dissatisfaction with service recovery, in terms of process and interpersonal justice. Satisfaction with service recovery had a significant effect on all the behavioral results of the users studied. The university image had no moderating effect on the relation between the dimensions of justice and satisfaction with service recovery. |

References

- He, F.; Deng, Y.; Li, W. Coronavirus disease 2019: What we know? J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Pizzol, D.; Marotta, C.; Antunes, M.; Racalbuto, V.; Veronese, N.; Smith, L. Coronavirus Diseases (COVID-19) Current Status and Future Perspectives: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Bouvier, N.; Wexler, A.S.; Ristenpart, W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: Does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Vaishya, R.; Deshmukh, S. Areas of academic research with the impact of COVID-19. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, K.; Tham, W.Y.; Yin, Y.; Cohodes, N.; Thursby, J.G.; Thursby, M.; Schiffer, P.; Walsh, J.; Lakhani, K.R.; Wang, D. Quantifying the Immediate Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Scientists. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Z.N.M. Technologies for Digital, Distance and Open Education: Defining What are Those. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, R.D.O.S.; Franco, A.P. DA DOCÊNCIA PRESENCIAL À DOCÊNCIA ONLINE: APRENDIZAGENS DE PROFESSORES UNIVERSITÁRIOS NA EDUCAÇÃO A DISTÂNCIA. Educ. Em. Rev. 2019, 35, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarian, M.; Abdollahi, M.R.; Nathan, G.J. Preliminary evaluation of a novel solar bubble receiver for heating a gas. Sol. Energy 2019, 182, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, E. On the Prevalence of Aperiodicity in Simple Systems—Global Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gleick, J.C.-A. C. de uma nova C., 4th ed.; Campus: São Paulo, Brasil, 1991; 310p. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, F.; Carvalho, A. Administração e Caos: Uma Estreita Relação. Rev. Ciências Gerenc. 2007, 11, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. Chaos theory as a model for managing issues and crises. Public Relat. Rev. 1996, 22, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R. Citation Analysis and Impact Factor Trends of 5 Core Journals in Occupational Medicine, 1975–1984. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2010, 65, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, E. Is citation analysis a legitimate evaluation tool? Science 1979, 1, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, W.W.; Koput, K.W.; Smith-Doerr, L. Interorganizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, K.M.; Kane, M.; Trochim, W.M.K. Evaluation of large research initiatives: Outcomes, challenges, and methodological considerations. New Dir. Eval. 2008, 2008, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.W. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Am. Ethnol. 1997, 24, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; Griffith, B.C. Author cocitation: A literature measure of intellectual structure. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1981, 32, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, J.T.; Kahn, K.B. A Framework of Logistic Reserarch. J. Bus. Logist. 1995, 16, 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Geaney, F.; Scutaru, C.; Kelly, C.; Glynn, R.W.; Perry, I.J. Type 2 Diabetes Research Yield, 1951–2012: Bibliometrics Analysis and Density-Equalizing Mapping. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Кештов, М.Л.; Куклин, С.А.; Бузин, М.И.; Годовский, Д.Ю.; Хохлов, А.Р. СИНТЕЗ И ФОТОФИЗИЧЕСКИЕ СВОЙСТВА ПОЛУПРОВОДНИКОВЫХ МОЛЕКУЛ Д1–А–Д2–А–Д1-СТРУКТУРЫ НА ОСНОВЕ ПРОИЗВОДНЫХ ХИНОКСАЛИНА И ДИТИЕНОСИЛОЛА ДЛЯ ОРГАНИЧЕСКИХ СОЛНЕЧНЫХ ФОТОЭЛЕМЕНТОВ. Дoклады Академии наук 2016, 469, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School Closure and Management Practices during Coronavirus Outbreaks Including COVID-19: A Rapid Systematic Review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal. 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. COVID-19 and Higher Education: Today and Tomorrow IMPACT Analysis, Policy Responses and Recommendations; UNESCO, IESALC: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wooliscroft, B. Macromarketing the Time is Now. J. Macromark. 2020, 40, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K. Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus 2020, 12, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawano, S.; Kakehashi, M. Substantial Impact of School Closure on the Transmission Dynamics during the Pandemic Flu H1N1-2009 in Oita, Japan. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Van Kerckhove, K.; Coletti, P.; Poletto, C.; Bossuyt, N.; Hens, N.; Colizza, V. The impact of regular school closure on seasonal influenza epidemics: A data-driven spatial transmission model for Belgium. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, C.C.; Erhart, L.M.; Jehn, M. Effect of School Closure on the Incidence of Influenza Among School-Age Children in Arizona. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewin, V. Five tips for moving teaching online as COVID-19 takes hold. Nature 2020, 580, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, R.; Weder, B. Economics in the Time of COVID-19; CEPR Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokowski, A.P.; Kowal, M.; Sorokowska, A.; Lebuda, I.; Białek, M.; Kowalska, K.; Wojtycka, L.; Karwowski, M. Dread in Academia—How COVID-19 Affects Science and Scientists; Institute of Psychology, University of Wroclaw: Wroclaw, Poland, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Corbera, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Ruiz-Mallén, I. Academia in the Time of COVID-19: Towards an Ethics of Care. Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W. COVID-19 Pandemic and the Digital Revolution in Academia and Higher Education; Prague Business School: Prague, Czech Republic, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dohaney, J.; De Roiste, M.; Salmon, R.A.; Sutherland, K. Benefits, barriers, and incentives for improved resilience to disruption in university teaching. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, C.; Dellazzana-Zanon, L.; Weschler, S.; Fabretti, R.; Rocha, K. COVID-19: Implications and Applications of Positive Psychology in Times of Pandemia. Estud. Psicol. 2020, 37, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Polizzi, C.; Lynn, S.J.; Perry, A. Perspective Article Stress and Coping in the Time of COVID-19: Pathways to Resilience and Recovery. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 17, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A.; Dwivedi, M. Pessimism towards Optimism: Empowering University Students amid COVID-19. Tathapi Ugc. Care J. 2020, 19, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Inouye, D.W.; Underwood, N.; Inouye, B.D.; Irwin, R.E. Support early-career field researchers. Science 2020, 368, 724–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniscuaski, F.; Reichert, F.; Werneck, F.P.; De Oliveira, L.; Mello-Carpes, P.B.; Soletti, R.C.; Almeida, C.I.; Zandona, E.; Ricachenevsky, F.K.; Neumann, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on academic mothers. Science 2020, 368, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omary, M.B.; Eswaraka, J.R.; Kimball, S.D.; Moghe, P.V.; Panettieri, J.R.A.; Scotto, K.W. The COVID-19 pandemic and research shutdown: Staying safe and productive. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2745–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, L.B. Supporting Learners in a Time of Crisis. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briner, R.B.; Denyer, D. Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis as a Practice and Scholarship Tool. In Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis as a Practice and Scholarship Tool; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hadengue, M.; De Marcellis-Warin, N.; Warin, T. Reverse innovation: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2017, 12, 142–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, W.; Katherine, M. Visualizing a Discipline: An Author Co-Citation Analysis of Information Science, 1972–1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekundayo, T.C.; Okoh, A.I. A global bibliometric analysis of Plesiomonas-related research (1990–2017). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.; Miskon, S.; Fielt, E. A Systematic, Tool-Supported Method for Conducting Literature Reviews. In ECIS 2011 Proceedings [19th European Conference on Information Systems]; AIS Electronic Library (AISeL)/Association for Information Systems: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Treinta, F.T.; Filho, J.R.D.F.; Sant’Anna, A.P.; Rabelo, L.M. Metodologia de pesquisa bibliográfica com a utilização de método multicritério de apoio à decisão. Production 2013, 24, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. Networks and performance of creative cities: A bibliometric analysis. City Cult. Soc. 2020, 20, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2017, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: A simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, C.P.; Walsh, A. An exploratory quantitative case study of critical thinking development through adult distance learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 68, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herodotou, C.; Rienties, B.; Hlosta, M.; Boroowa, A.; Mangafa, C.; Zdrahal, Z. The scalable implementation of predictive learning analytics at a distance learning university: Insights from a longitudinal case study. Internet High. Educ. 2020, 45, 100725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods—Applied Social Research Methods Series, 6th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, J.; Birks, M. Qualititave Methodology: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D.A.; Muñoz, F.-F.; Vázquez, F.J. Innovation in online higher-education services: Building complex systems. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, A.B.; Banyard, P. Engagement in Distance Education Settings: A Trend Analysis. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, I.; Merz, T. Lone Wolves in Distance Learning? Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2020, 12, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Lin, C.-H.; Kwon, J.B. The impact of learner-, instructor-, and course-level factors on online learning. Comput. Educ. 2020, 150, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, K.; Firssova, O.; De Beeck, I.O.; Van Der Stappen, E.; Stoyanov, S.; Henderikx, P.; Buchem, I. Learner skills in open virtual mobility. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danka, I. Motivation by gamification: Adapting motivational tools of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) for peer-to-peer assessment in connectivist massive open online courses (cMOOCs). Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 66, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, B.R.; Jansz, M. Reducing distance through online international collaboration. ELT J. 2019, 74, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, E. The impact of COVID-19 on food retail and food service in Canada: Preliminary assessment. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, A.P. Risk management in Canada’s agricultural sector in light of COVID-19. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, G. Economic thoughts on COVID-19 for Canadian food processors. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawley, C. Potential impacts of COVID-19 on Canadian farmland markets. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercammen, J. Information-rich wheat markets in the early days of COVID-19. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, B.J. Food security and Canada’s agricultural system challenged by COVID-19. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weersink, A.; Von Massow, M.; McDougall, B. Economic thoughts on the potential implications of COVID-19 on the Canadian dairy and poultry sectors. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranfield, J.A.L. Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.S. Agriculture, transportation, and the COVID-19 crisis. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.M.; A Mullican, L.; Tse, Z.T.H.; Yin, J.; Zhou, X.; Bs, D.K.; Fung, I.C.-H.; Mph, L.A.M. Unplanned Closure of Public Schools in Michigan, 2015–2016: Cross-Sectional Study on Rurality and Digital Data Harvesting. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorhouse, B.L. Adaptations to a face-to-face initial teacher education course ‘forced’ online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, M.; Yasmin, M.; Alvi, M.Y. COVID-19: A threat to educated Muslim women’s negotiated identity in Pakistan. Gend. Work. Organ. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.A.; Shaw, G.P. Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. J. Lead. Stud. 2020, 14, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grint, K. Leadership, management and command in the time of the Coronavirus. Leadership 2020, 16, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.N.F.; Blanchflower, D.G. US and UK labour markets before and during the COVID-19 CRASH. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2020, 252, R52–R69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, D. The Environmental Impacts of the Coronavirus. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 76, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, D.; Kagawa, F. Climate change and coronavirus: A confluence of two emergencies as learning and teaching challenge. In Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, 30. Policy & Practice; Centre for Global Education: Belfast, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Addo, P.C.; Jiaming, F.; Kulbo, N.B.; Liangqiang, L. COVID-19: Fear appeal favoring purchase behavior towards personal protective equipment. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyabaladevan, P. COVID-19: An FY1 on the frontline. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25, 1759869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Chen, X.; Shi, W. Impacts of social and economic factors on the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 33, 1127–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenett, S.J. Sicken Thy Neighbour: The Initial Trade Policy Response to COVID-19. World Econ. 2020, 4, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavins, J. Unprepared for financial shocks: Emergency savings and credit card debt. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.L. The COVID-19 Risk Perception: A Survey on Socioeconomics and Media Attention. Economics Bulletin. AccessEcon 2020, 401, 758–764. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, N.; Finkelstein, R.A.; Howell, J.; Rajwani, K.; Ching, K. Telesimulation for COVID-19 Ventilator Management Training With Social-Distancing Restrictions During the Coronavirus Pandemic. Simul. Gaming 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, A.; Harrabi, B.; Mohr, M.; Krustrup, P. Physical activity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Specific recommendations for home-based physical training. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. The Post: A token woman leader’s transformation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2020, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, S.K. Co-Authorship and Co-Occurrences Analysis Using Bibliometrix r-Package: A Case Study of India and Bangladesh. Ann. Libr. Inf. Stud. 2019, 66, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, J.; Kear, K.; Donelan, H.; Heaney, C.A. Students’ experiences of anxiety in an assessed, online, collaborative project. Comput. Educ. 2020, 143, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.; Cowan, J.; Irvine, L.; Williams, J. An Exploration Into the Importance of a Sense of Belonging for Online Learners. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelcher, S.; Yang, D.; Trespalacios, J.; Snelson, C. Connecting online students to their higher learning institution. Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppi, S.; Muukkonen, H.; Suorsa, T.; Takala, M. I still miss human contact, but this is more flexible—Paradoxes in virtual learning interaction and multidisciplinary collaboration. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 51, 1101–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, D. Exploring the Roles of Social Presence and Gender Difference in Online Learning. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2020, 18, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetcova, I.; Lin, T.-J.; Glassman, M. Teacher Presence in a Different Light: Authority Shift in Multi-user Virtual Environments. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Park, S. Building a structural model of motivational regulation and learning engagement for undergraduate and graduate students in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 45, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chang, H.; Bryan, L. Doctoral Students’ Learning Success in Online-Based Leadership Programs: Intersection With Technological and Relational Factors. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm-Chapin, M.K.; Koszalka, T.A. Graduate Students’ Use and Perceived Value of Learning Resources in Learning the Content in an Online Course. TechTrends 2020, 64, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnova, L.; Shurygin, V. Blended Learning of Physics in the Context of the Professional Development of Teachers. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.; Lim, S.C.J.; Lai, C.S. Assessment of Teaching Practice Competency among In-Service Teacher Degree Program PPG. in Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia. J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2020, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.Y.; Dongol, B. A blockchain-enabled e-learning platform. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, P.S. Can the Game-Based Learning Come? Virtual Classroom in Higher Education of 21st Century. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, E. Code-switching in conversation-for-learning: Creating opportunities for learning while on study abroad. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, T.A.; Callison, M.; Myers, R.D.; Berry, A.H. Facilitating Authentic Learning Experiences in Distance Education: Embedding Research-Based Practices into an Online Peer Feedback Tool. TechTrends 2020, 64, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilinc, B.K.; Yazici, B.; Gunsoy, B.; Gunsoy, G. Perceptions and Opinions of Graduates about the Effects of Open and Distance Learning in Turkey. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.A.; Cao, H.; Zhang, W. Prediction of students’ early dropout based on their interaction logs in online learning environment. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.A.M.L.; Lima, J.T.D.O.; Da Silva, B.H.; Sales, M.J.T.; De Orange, F.A. Development, implementation and evaluation of a management specialization course in oncology using blended learning. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Who opens online distance education, to whom, and for what? Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortagus, J.C.; Yang, L.; Voorhees, N.; Riggs, S. Revenue Reconsidered: Exploring the Influence of Changes in Local and State Appropriations on Online Enrollment at Community Colleges. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-H.; Choi, S.-H. Virtual short-term intercultural exchange as an inclusive educational strategy: Lessons from the collaboration of two classes in South Korea and China. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltz, J.; Heckman, R. Using Structured Pair Activities in a Distributed Online Breakout Room. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiperez-Valiente, J.A.; Halawa, S.; Slama, R.; Reich, J. Using multi-platform learning analytics to compare regional and global MOOC learning in the Arab world. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146, 103776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A.; Kotzee, B. UK university part-time higher education: A corpus-assisted discourse analysis of undergraduate prospectuses. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapp, S.; Boutté-Queen, N. The role of the US baccalaureate social work program director: A national survey. Soc. Work. Educ. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.A.; Frey, B.B.; Niileksela, C.; Lee, S.W.; Nong, A.; Alharbi, F. The Role of Task Value and Technology Satisfaction in Student Performance in Graduate-Level Online Courses. TechTrends 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Xiu, G.; Khan, I.; Shahbaz, M.; Riaz, M.U.; Abbas, A. The moderating role of intrinsic motivation in cloud computing adoption in online education in a developing country: A structural equation model. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2019, 21, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littenberg-Tobias, J.; Valiente, J.R.; Reich, J. Studying learner behavior in online courses with free-certificate coupons: Results from two case studies. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2020, 21, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, C.; Gallagher, S. Postgraduate Online Teaching in Healthcare: An Analysis of Student Perspectives. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. The Relationships between Self-Efficacy, Task Value, and Self-Regulated Learning Strategies in Massive Open Online Courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Garcia, J.; Gallardo, K. Peer Feedback in Learner-Learner Interaction Practices. Mixed Methods Study on an XMOOC. Electron. J. E-Learn. 2020, 18, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Martinasek, M.P.; Carone, K.; Sanders, S. High School Students’ Perceptions of Traditional and Online Health and Physical Education Courses. J. Sch. Health 2020, 90, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinacori, B.C. How Nurse Educators Perceive the Transition From the Traditional Classroom to the Online Environment. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2020, 41, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gay, G.H.; Betts, K. From Discussion Forums to eMeetings: Integrating High Touch Strategies to Increase Student Engagement, Academic Performance, and Retention in Large Online Courses. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.; Cuttler, C. Open to Open? An Exploration of Textbook Preferences and Strategies to Offset Textbook Costs for Online Versus On-Campus Students. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Khan, M.M.; Khan, R.A.; Mujtaba, B.G. The Relationship between Social Capital and Psychological Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Internet Marketing. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2020, 1, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzalp, N.; Bahçivan, E. The Online Learning Self-Efficacy Scale: Its Adaptation into Turkish and Interpretation According to Various Variables. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 2020, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuij, S.M.; on behalf of the INSTRUCT Project Group; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Labrie, N.H.M.; Hulsman, R.L.; Kersten, M.J.; Van Dulmen, S.; Smets, E.M.; De Haes, H. Developing a digital training tool to support oncologists in the skill of information-provision: A user centred approach. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedra, M.; Bennani, S. Competency Based Approach: Modeling and Implementation. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J. Modelo de Referencia Para La Enseñanza No Presencial En Universidades Presenciales Reference Model for Virtual Education at Face-to-Face Universities. Campus Virtuales 2020, 9, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shonfeld, M.; Magen-Nagar, N. The Impact of an Online Collaborative Program on Intrinsic Motivation, Satisfaction and Attitudes towards Technology. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2017, 25, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I. Pronunciation Development and Instruction in Distance Language Learning. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2020, 24, 86–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vershitskaya, E.R.; Mikhaylova, A.V.; Gilmanshina, S.I.; Dorozhkin, E.M.; Epaneshnikov, V.V. Present-day management of universities in Russia: Prospects and challenges of e-learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2019, 25, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andoh, R.P.K.; Appiah, R.; Agyei, P.M. Postgraduate Distance Education in University of Cape Coast, Ghana: Students’ Perspectives. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn 2020, 21, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al Said, N. Mobile Application Development for Technology Enhanced Learning: An Applied Study on the Students of the College of Mass Communication at Ajman University. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlatchan, M.; Watson, G.S. Enhancing instructor credibility and immediacy in online multimedia designs. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2019, 68, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, K.; Rees, L.; Levett, B.; Sitnikova, E.; Townsend, D. Efficacy of structured peer critiquing in postgraduate coursework. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando, A.J.; Kanagusiko, A.G.; Flores, C.M.; Carrillo, J.M.; Mendoza, J.A.; Contreras, L.C.A.; Quiroz-Rivera, S. Motivación hacia las matemáticas de estudiantes de bachillerato de modalidad mixta y presencial. Rev. Educ. 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, P.; Kisman, Z. Information and communication technology utilization effectiveness in distance education systems. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Lotz, N.; Holden, G. A longitudinal study of virtual design studio (VDS) use in STEM distance design education. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2020, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delnoij, L.E.; Dirkx, K.J.; Janssen, J.P.; Martens, R.L.; Laurie, E.D.; Kim, J.D.; Janssen, J.; Rob, L.M. Predicting and resolving non-completion in higher (online) education—A literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasandy, T.; Nurlaila, I.; Titan, T.; Lena, L. Implementation of “ADAB” to Hearing Impaired Student as Learning Innovation in the Data and Text Mining Course, Information System Distance Learning, Binus Online Learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsby, C.L.T.; Bryant, A. “I felt like I was missing out on something”: An evaluation of using remote technology in the classroom. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.B.M.; Piaralal, S.K.; Bin Daud, Y.R.; Bin Mohamed, B. An Empirical Study on Service Recovery Satisfaction in an Open and Distance Learning Higher Education Institution in Malaysia. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stages | Description |

|---|---|

| Formulating the issue | Mapping and bibliometric analysis of the publications studied in management and education |

| Research protocol | String 1: “covid 19” or “coronavírus” and “scientificproduction” String 2: “covid 19” or “coronavírus” and “distanceeducation” or “online education” or “schoolclosures” or “distancelearning” String 3: “covid 19” or “coronavírus” and “academics” |

| Data search | WOS (26/5/2020) |

| Eligibility criteria | String 1 and 3: Categories of Web of Science = (business finance or management or economics or education educational research) and document types = (article or review) String 2: categories of Web of Science = (business finance or management or economics or education educational research) and document types = (article or review) and years of publication (Limited to 2020, as only research following the emergence of COVID 19 is of interest) = (2020) |

| Data extraction | For Excel and Bibtex format |

| Analysis and synthesis of results | Qualitative (descriptive) and quantitative (bibliometrics) |

| Discussion of the results | Exhaustive content analysis |

| Items | Results |

|---|---|

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc.) | 48 |

| Documents | 93 |

| Average years from publication | 0.0133 |

| Average citations per document | 0.1067 |

| References | 2813 |

| Authors | 202 |

| Authors of single-authored documents | 17 |

| Authors of multi-authored documents | 185 |

| Documents per Author | 0.371 |

| Co-Authors per Document | 2.69 |

| Collaboration Index | 3.19 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M.; Silva, R. COVID-19 and Disruption in Management and Education Academics: Bibliometric Mapping and Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187362

Rodrigues M, Franco M, Silva R. COVID-19 and Disruption in Management and Education Academics: Bibliometric Mapping and Analysis. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187362

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Margarida, Mário Franco, and Rui Silva. 2020. "COVID-19 and Disruption in Management and Education Academics: Bibliometric Mapping and Analysis" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187362

APA StyleRodrigues, M., Franco, M., & Silva, R. (2020). COVID-19 and Disruption in Management and Education Academics: Bibliometric Mapping and Analysis. Sustainability, 12(18), 7362. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187362