1. Introduction

Tibet, located in the southwest of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, is one of the five ethnic autonomous regions in Mainland China. As a main place of habitation for Tibetans historically, more than 90% of its population are Tibetans [

1]. It is an important gateway for China to South Asia, bordering Burma, India, Bhutan, Nepal and Kashmir. Under the background of the Belt and Road Initiative proposed by the Chinese government in the new decade, Tibet is now facing unprecedented opportunities and challenges regarding integration into the greater world while maintaining its own cultural heritage. When we look deeper into the matter from the perspective of language, we may see that local Tibetans’ demand for language has been affected by the changing context of their expanding communication circles involving people of different native languages and cultures. While their universities and colleges, positioned as a link between the global and the local, are enjoying easier access to the outer world, as well as a greater potential to influence changes in the local society, they also undertake the responsibility for a change to equip their students with multilingual abilities to adapt to this new environment [

2].

Higher education in Tibet can be traced back to 1950s, when training programs were founded for Tibetan leading cadres in management. Now, in Tibet, there are seven higher education institutions (HEIs), including four undergraduate institutions and three junior colleges.

Mainly serving the needs of Tibet’s economic and social development, they usually offer preferential policies to admit Tibetan students within the autonomous region. However, students outside the autonomous region are also welcomed, but the quotas are lower. Thus, the student population in these HEIs is usually a mix of Tibetan and Han students, with a few from other minority groups. How better to educate these students and prepare them linguistically in a changing context—so that they can better meet the needs of the social and economic development of Tibet—is one question. At the same time we ask, how can we cultivate local talents according to the cultures and needs of the local community so as to ensure the sustainability of educational practices in HEIs in Tibet? These are all realistic problems that HEIs in Tibet must face.

The present study, situated in one of the higher education institutions in Tibet, aims to explore the sustainability of the multilingual language policy, following the paradigm of the language policy ecology. It is hoped that the findings will provide us with an insight into the current multilingual language policy implemented in this particular HEI, and further offer valuable information for the formulation of sustainable multilingual policies for Chinese minority education at the higher education level.

2. The Ecology of Language Policy

In general, language policy (LP) is “concerned with the decisions people make about languages and their use in society” [

3] (p. 278), which involves the identification of language problems, the formulation of various alternatives and making a decision on which norm (a language or a dialect) is to be promoted in a society and its educational system [

4]. Language policy can be either explicitly documented in public reports or regulations, which outline specific guidelines, or implicitly revealed in the lack of management or support for certain languages. As the ecological approach to the study of language policy began to thrive, the focus of language policy studies shifted from being nation-centered to being locally centered. Language policy has been placed at the heart of an ecosystem with various forces at work: linguistic as well as non-linguistic, macro as well as micro. A large range of natural and cultural ecological factors have been identified as underlying mechanisms that dictate the de facto language policy in place.

Under the paradigm of language ecology, studies of language policy have explored ways of maintaining a maximum diversity of languages by identifying the ecological factors that sustain linguistic diversity [

5]. Spolsky [

6] put forward a concept of the ecology of language policy in which language practices, language beliefs, and language management are taken as three components that interact with each other in complex, wider contexts under the influence of all types of conditions to form the language policy of a speech community. It calls upon researchers to pay attention to several dimensions of multilingualism at the same time, and to the relationships among the languages, among the social contexts of the languages, and among the speakers of the languages. Shohamy [

7] further concluded that a variety of mechanisms lie at the heart of the battle between ideology and practice within the language policy framework, such as language in education, language in public spaces, and the language attitudes and beliefs held by the public. In this battle, power rests not only with the state or within a policy text; language policy is enacted by educational practitioners through discursive practices that operate in relation to some authoritative criteria [

8,

9]. Thus, to understand de facto language policy in practice, in addition to analyzing explicit language policy documents, there is also a need to examine all of the mechanisms that dictate and impose the language practices covertly and implicitly.

3. Language Education Policy in Higher Education Institutions

Language education policy (LEP) is “a species of language policy” [

10] (p. 118) that is “concerned with the organization of language teaching within the formal educational system” [

11] (p. 5), and which dictates what languages are to be taught as subjects and what languages are to be used as a medium of instruction in schools. “LEP is considered a form of imposition and manipulation of language policy as it is used by those in authority to turn ideology into practice through formal education.” [

7]. In this sense, language education policy is crucial, since no matter what the subject is, students can only acquire new knowledge through language instruction; consequently, it helps shape the language use patterns of the younger generation. However, discontinuities can always be found between the top-down language education policies and the local enactment of them, as implementation decisions and language policy usually rest on the negotiation and interpretation of policy mandates by multiple stakeholders [

12].

As regards LEP in universities, Grin [

13] recommended that five types of activities at three levels of action should be analyzed; namely languages taught as subjects, languages of instruction, languages in research, languages in administration, and languages of external communication at the levels of policy orientations, pedagogical issues and organizational challenges. Three macro factors—namely, the situational factor, the operational factor and the outcome factor—have been identified by Beardsmore [

14] as the main variables relating to language policies in higher educational settings. In the case of HEIs, as suggested by Fortanet-Gómez [

15], the situational factor includes the students, population diversity, opportunity for language use, status of languages, and attitudes, etc.; the operational factor includes the curriculum, subjects, initial literacy, exit criteria, materials, teachers, language strategies and involvement of the whole institution, etc. A major difference between secondary and tertiary education lies in the decrease in the relevance of parents and the increase in the relevance of other stakeholders in the specific social environment, such as potential employers and decision makers, etc. [

15]. Last, the outcome factor mainly relates to the achievements expected in a multilingual program, but also covers students’ senses of integration and motivation, as well as their satisfaction when learning in a multilingual setting. It functions as a decisive power over the continuation of the program.

Thus, to gain a good overview of the design of the language policy and multilingual program for a particular HEI, it is necessary to fully understand how all these variables are interwoven and triangulate with each other to form the de facto LEP enforced.

5. Research Findings

5.1. The Linguistic Resources of the HEI Students in Tibet

LEPs’ implementation in HEIs is an extension of LEPs of high school. Students’ initial literacy, to a large extent, dictates the formulation of LEPs in the HEI. To obtain a profound understanding of the current policy, it is necessary to be fully aware of students’ linguistic resources when they entered higher education. A survey of the participants’ language learning experiences before they entered the HEI showed that Chinese is indisputably the dominant language, regardless of their ethnic group or home territory. Although among the 276 participants, 123 spoke Chinese as mother-tongue and 148 spoke Tibetan as mother-tongue, all of the participants admitted that they started to learn Chinese literacy before or from the very beginning of their primary education, regardless of the location of their primary school. Thus, before they entered the HEI, the majority had more than 10 years’ experience of learning Chinese literacy. However, the situations for Tibetan and English learning were much more complicated. In terms of the age they started learning, it varied greatly for both Tibetan and Han students. Although around half of the participants started learning English from Grade 3–6, quite a few started much earlier than that, but some did not learn any English at all until high school. As for Tibetan, there was an apparent trend of polarization. Most participants from the TAR started learning Tibetan literacy when they started primary education, but participants from outside the TAR started learning Tibetan much later; indeed, most of them had only started learning after they entered the HEI. Details are presented in

Table 4.

It is obvious from the data above that, in regard to Tibetan language ability, large discrepancies between the students from the TAR and those from other places outside the TAR may exist. In contrast to the Tibetan students in the TAR, who started to learn Tibetan literacy from their primary school, most of those coming from outside the TAR had only started their Tibetan language learning after they entered the HEI. Thus, students’ ability in the Tibetan language may vary a lot. For Tibetan students, after years of study, it may be taken as a linguistic resource for them, but for Han students, Tibetan was a new language that could cause many problems for them. The wide difference in students’ Tibetan learning experience made it unlikely to be considered as a prior linguistic resource for all students.

On the other hand, Chinese, given the relatively similar learning experiences among all of the students and its status as the national language, demonstrated great potential to become the most important linguistic resource for all of the students. After years of elementary and secondary education in Chinese, most students would not have a problem in understanding Chinese instruction. In addition, being the dominant language in the wider society in China, Chinese is most likely to deliver an advantageous position in the educational domain as well.

The situation for English is different again. As a foreign language, although it seems to have been studied for quite a long time by many students, without social support in the wider society, the general level of their English ability was much lower than that of their Chinese. For Tibetan students, English was their third language. Their English language ability cannot be compared either to their mother-tongue (Tibetan) or the dominant language (Chinese). However, for most Han students, English was a second language they learned since their primary school, while Tibetan was a new language they had only had contact with since they entered the HEI. Their English language ability was mostly likely to be higher than their Tibetan. The relatively lower levels and unevenness of their language ability made it unlikely for either English or Tibetan to gain a dominant position in the HEI.

Furthermore, an investigation into the three distinct dialects of Tibetan used by Tibetan students in the HEI showed that the Weizang dialect was the main branch used. Among the 154 Tibetan students, 116 spoke the Weizang dialect as their mother tongue, accounting for 75% of all of the Tibetan participants. Another 35 students spoke the Kangba dialect as their mother tongue, which accounted for around 23% of the Tibetan participants. The Ando dialect was seldom spoken, having only three users. As for the dialects of Chinese, Putonghua and Sichuanhua were the two main branches, which accounted for around 50% and 31% of the Chinese mother-tongue speakers, respectively.

5.2. Policy Orientation of the LEP for the HEI

Trilingual education, the explicit LEP, as a guideline for language education in the HEI, was manifested directly by the curriculum set down by the school authority. It is an important document that reflects the official ideology and policy orientations. By examining the common curriculum for students of different majors in the HEI, it was found that Chinese, Tibetan and English were all compulsory courses for the students enrolled. However, different requirements were set for students of different linguistic backgrounds.

Regarding the Tibetan language, a three-tiered curriculum was set up. The top class was for Tibetan students from within the autonomous region. After the course, all of the students needed to pass the Tibetan language proficiency test, level 4. The intermediate class was for Tibetan students from other areas, or those who had only one Tibetan parent. They needed to pass the Tibetan language proficiency test, level 2, after the course. The bottom class was for Han students in the HEI, who needed to pass the Tibetan language proficiency test, level 1. Although all of the students enrolled needed to take the Tibetan language class, the evaluation criteria varied according to their initial literacy.

Similar policies were implemented for the subjects of Chinese and English as well. For the Chinese language class, the students were divided into three levels according to their Chinese scores in the College Entrance Exam. Those who scored higher than 90 points were grouped into the top class; those who scored between 80 and 89 were grouped into the intermediate class; those whose score was below 79 were placed in the bottom class. All of them needed to take a Chinese language class for one semester. On the other hand, English classes were divided into two levels, the high level being comprised of students whose English scores were higher than 90 points in the College Entrance Exam, and those below that, who were grouped into the elementary level. What was particular for the curriculum of English is that English classes would last for four semesters, while Chinese and Tibetan only lasted for one semester each. The importance of English in the explicit LEP was self-evident. For both Chinese and English, there were no level requirements imposed on students, which effectively loosened the exit criteria and reduced the pressure on students.

Besides the three common compulsory courses for all students mentioned above, the HEI also offered French and Japanese as optional foreign languages for students majoring in English. They could select one as their second foreign language in their third or fourth year of study.

In all, an overview of the explicit curriculum showed that Chinese, Tibetan and English, as three common language courses, were all actively promoted in the HEI. Unlike other mainstream higher institutions in China, setting the compulsory course of the Tibetan language for all the students represented a typical feature of the multilingual LEPs in this HEI.

5.3. Language Practice In and Out of the Classroom in the HEI

Language practice was an important aspect that reflected the de facto LEP. The languages that students and teachers applied in and out their classroom mirrored the vitality of the corresponding languages in the contexts of the HEI. By exploring the language application patterns exercised by participants in and out of the classroom, it was found that Chinese was the most vital language in the HEI, followed by Tibetan and English.

As the questionnaire results revealed, inside the classroom, apart from the language course itself, Chinese was the foremost language used for course instructions, course materials and course exams. Although in a few cases Tibetan would be used, it was used along with Chinese. For communication between teachers and students, Chinese gained predominance as well. In total, 193 participants reported that they would only use Chinese to communicate with their teachers inside the classroom. However, a few admitted that—besides Chinese—they would sometimes also use a little Tibetan or English in the classroom, but it depended on whether their teacher was a Tibetan or not. As for communications among peer students in the classroom, the situation was similar. While Chinese occupied a dominant position, a number of students reported that they would also use Tibetan as well. A few Tibetan students even said they would only use Tibetan to communicate with peer students.

English was found to be the least frequently used language. Only around 40 students admitted that they had ever received any course instructions or course and exam materials in English along with Chinese or Tibetan. Communication in English was even less frequent, especially among peer students (see

Table 5).

From the table above, it can be seen that, in the classroom setting, Chinese gained an overwhelming superiority. However, concerning the languages used outside the classroom, there was a different picture. Although Chinese was still used a lot, especially in some formal contexts, there was an obvious increase in the use of Tibetan in more casual situations. The data obtained from the questionnaire demonstrated that the Tibetan language was rather active in students’ extracurricular lives, especially for Tibetan students. For example, in celebration parties on campus, 155 participants responded that they would use the Chinese–Tibetan language, among whom 141 were Tibetan students and 14 were Han students. In total, 133 Tibetan students expressed that they would listen to both Chinese and Tibetan programs of campus broadcasting. Although Tibetan programs were fewer than that of Chinese, they had successfully attracted a large audience. It was apparent that Tibetan language was vital to Tibetan students’ extracurricular lives in spite of the dominance of Chinese. However, with regard to the use of English, the situation was not so positive. Even fewer participants, Han as well as Tibetan students, said they would use any English in their lives outside the classroom (see

Table 6).

From the data above, we can see that Chinese was active in every aspect of students’ lives, especially in the areas of academic studies, a position which was not matched by any other language, even though this HEI was located in Tibet. However, in lives outside the classroom, while Chinese was found to be used a lot by participants, Tibetan still occupied an important position. Tibetan was very vital and active in students’ social lives. However, with regard to English, the picture was quite different. Due to lack of social functions in the local society, English was neither active as an academic language nor as a social language in students’ lives in the HEI.

5.4. Factors Relating to the LEP Management

As discussed above, the successful implementation of a multilingual project in a HEI involves multiple internal and external stakeholders [

16,

17]. Students, teachers, staff, future employers, policy makers and other relevant decision makers in the specific social environment are all determining factors of how the multilingual LEPs are applied and how the resources are allocated. The success and sustainability of the multilingual program in the HEI, to a certain extent, depends largely on the harmonious relationships among various internal and external stakeholders.

The results from the survey demonstrated that multilingual courses in this specific HEI had remained at an initial stage, in which Tibetan and English were mostly introduced as subjects but not used as media of instruction, except for the students who majored in language studies. At a broad level, most students reported that Chinese was the common instructional language for nearly all of the specialized or common required courses. As most classes had a mix of Han and Tibetan students, using Tibetan as the instructional language in the class was impractical because of the large discrepancies between their Tibetan language levels. Moreover, the linguistic background of the teachers also restricted the application of Tibetan as an instructional language. Data from the authority showed that, among the 622 full-time teachers in the HEI, around 35% are Han teachers. For those Han teachers, using the Tibetan language for instruction was a big challenge. Furthermore, a lack of learning materials in Tibetan was also a problem hindering Tibetan language instruction. Thus, with consideration of all these external factors, Chinese, with its relatively balanced proficiency level, was adopted as the most suitable language for all of the students.

From another perspective, students’ expectations of their advanced studies regarding their future careers played a significant role in shaping their language attitude, which further impacted the requirement and mode of the multilingual program in the HEI [

18,

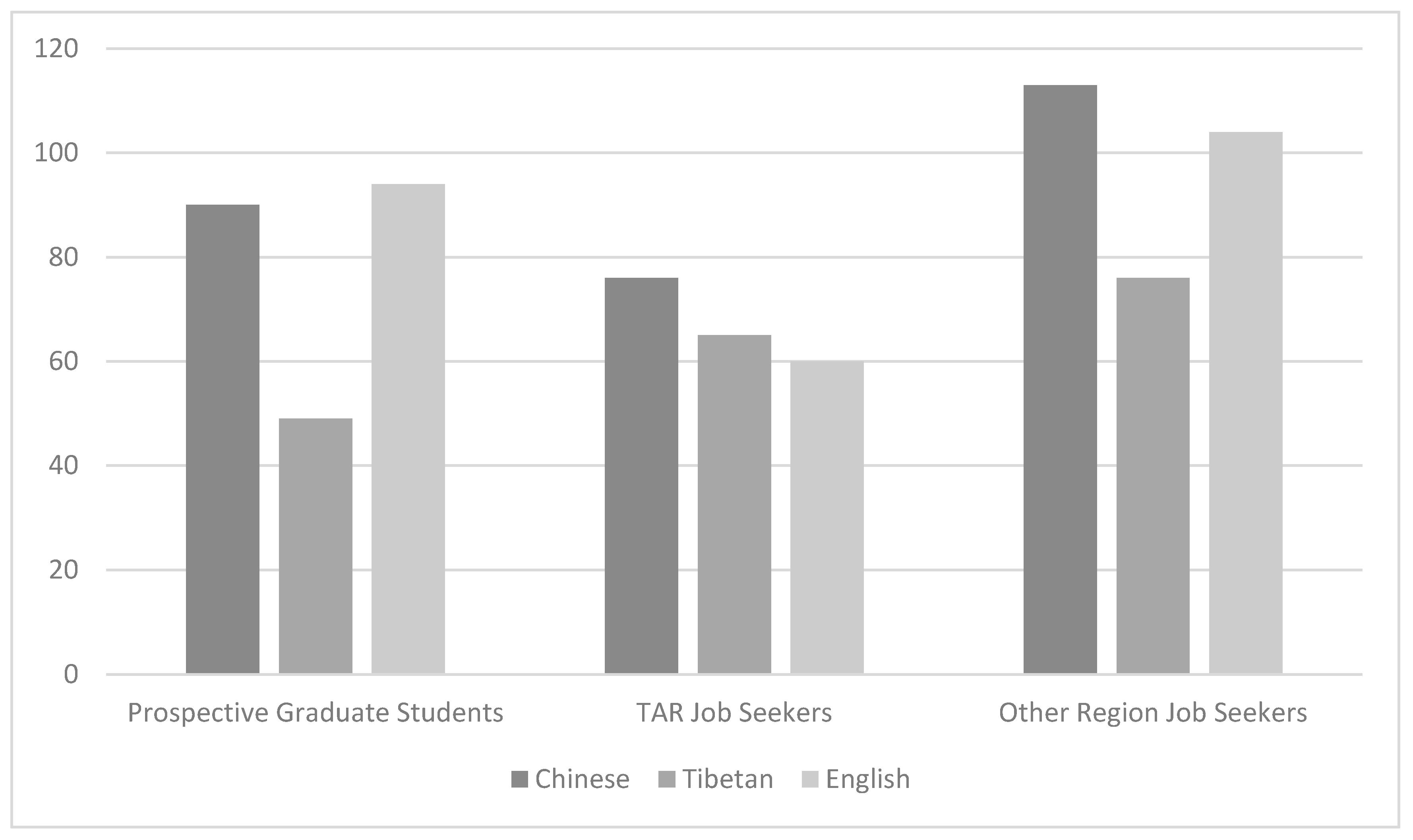

19]. The results of the questionnaire demonstrated that, among the 276 participants, 175 responded that they would consider furthering their study and prepare to apply for postgraduate studies, and 126 of them would choose to go to an institution outside the TAR. Under such a condition, Chinese and English languages were more important for students who wanted to further their study. As the major academic languages used in mainstream HEIs in China, Chinese and English are two channels to impart knowledge in their further studies. Besides this, English is also a mandatory subject in the post-graduate entrance exam, as all the students need to take the English exam and reach the passing score. Thus, the importance of Chinese and English cannot be overemphasized. However, students’ demand for Tibetan was much weaker, as usually there was no requirement for their Tibetan language ability in the post-graduate entrance exam. This provides a powerful explanation for why English was set as a compulsory course for four semesters in the HEI. However, on the other hand, students’ career planning also had a marked effect on their language attitude. Generally, there were two choices for them; finding a job within the TAR or going outside to other places. A good many participants reported that they would stay in the TAR after graduation. For this group of students, the Tibetan language was of importance. Most of them recognized that they may need to use Tibetan and Chinese in their future jobs. Thus, for them, learning Tibetan well was a must. However, for those who wanted to work in other places, their demand for Tibetan learning was lower than that for Chinese and English. It can be seen that different plans for their future lives led to a divergent demand for different languages in their current study (see

Figure 1). All three languages had many potential learners.

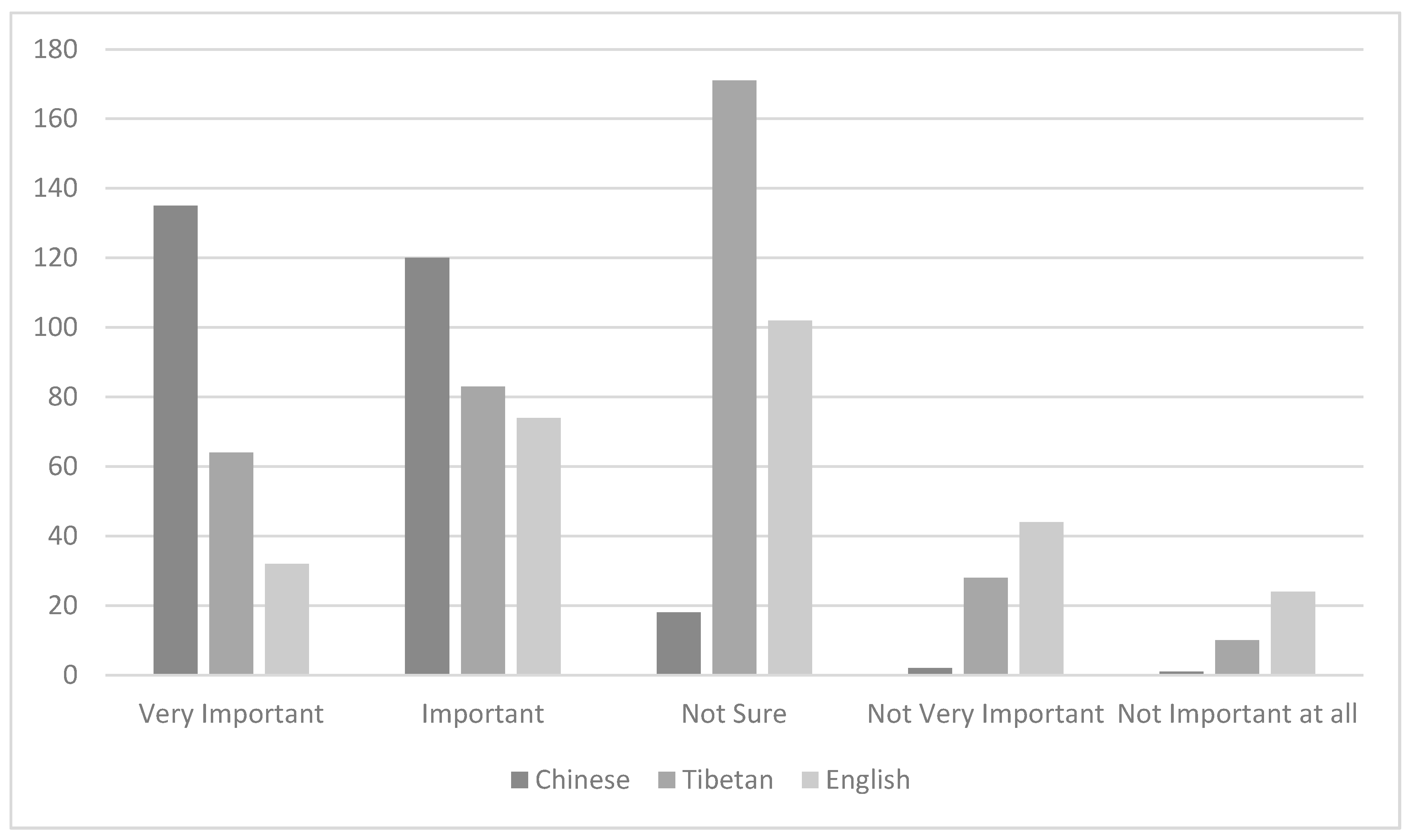

Further, languages that related to students’ academic achievements also determined the effort that students put into that language. The questionnaire results revealed that participants’ perceptions of the contributions of each language to their academic achievements in the HEI varied a lot. Chinese language proficiency was perceived by most participants as being very important or important for their study in the HEI, while the learning of Tibetan and English was considered less important (see

Figure 2).

From the data above, it can be seen that—either for their future development or their current study—the Chinese language was considered the most important. The positive attitudes towards Chinese consolidated the dominance of Chinese in the HEI. However, students’ attitudes towards Tibetan and English were complicated and less positive. As an important internal factor influencing language learning, language attitude was a crucial element that needed to be considered in the process of LEP implementation. How to balance students’ language learning attitude and the mode of a multilingual program was a big question confronting the LEP executors in the HEI.

6. Discussion

By analyzing activities related to LEP in the HEI at three different levels, the ecology of the LEP was clearly presented. In this ecological system, various linguistic—as well as social—factors were functioning together to maintain a balance among Chinese, Tibetan and English. In general, to sustain the diversity of languages in the context of the HEI, the following challenges need to be addressed.

6.1. Heritage Language versus Dominant Language versus Foreign Language

Tibetan, Chinese and English are three languages used in the HEI, each occupying a unique position in students’ campus lives. Among the three languages, Tibetan, as the heritage language in the local society, is a distinct feature of the HEI’s trilingual education. Although the academic function of the Tibetan language was dwarfed by Chinese in the academic settings, the HEI has persisted in setting Tibetan language as a compulsory course for all the students. The underlying ideology for this policy is apparent. On the one hand, it encouraged Tibetan students to maintain their mother-tongue, while on the other hand, it invited more students to learn the Tibetan language, so as to increase its vitality on campus. Chinese is still the dominant language in the HEI, both in and out of the classroom. Since the major student population is a mix of Tibetan and Han students, how the demands of students with different linguistic backgrounds are met is crucial. Chinese has thus won a high acceptance among students and teachers as a medium for instruction and communications. Despite its being the mother-tongue for Han students and second language for Tibetan students, Chinese is the common linguistic resource for them all. The dominant position of Chinese in the HEI is also strengthened by its social and economic functions in the wider society. English, a popular foreign language in mainstream HEIs in China, also occupied a position here. Following the norm, the HEI set English as a compulsory foreign language course for all of the students for four semesters. For those students who want to apply for postgraduate programs after graduation, foreign language is a mandatory subject they need to pass in the entrance examinations; for those who want to find a good job outside the TAR, English is a stepping stone for them to go higher. Thus, although it lacks social functions in campus lives, English as a foreign language has survived in the HEI.

Being the heritage language, dominant language and foreign language respectively, Tibetan, Chinese and English have achieved a certain kind of balance in students’ campus lives. The HEI has taken up its responsibility to help preserve the local heritage language, Tibetan, while embarking on the way of integrating it into mainstream education by offering language courses of the dominant language and foreign language.

6.2. Language of Instruction and Language of Subject

Which language should be considered as the appropriate language for instruction in the HEI? Which languages should be taught as a subject? These questions always perplex the educators in a multilingual HEI. While offering local language instruction for minority students has long been recognized as right for the sustainable development of education [

20], to create more reasonable multilingual education practices to meet the micro-context of the HEI, a set of situational factors is involved in the evaluation process, in which population diversity and economics are two major concerns [

14,

21]. As we found in this specific HEI, the student population was mainly composed of two major parts, Han students and Tibetan students, accounting for 37.4% and 60.2% of the whole, respectively. Thus, the Tibetan language, though the common community language in Tibet, could hardly be used as an instructional language, since that would create huge obstacles for Han students, especially those coming from outside the TAR. However, on the other hand, although less than half of the students spoke Chinese as their mother-tongue, all of the students had received formal Chinese education for quite a long time. Theoretically, Chinese

Putonghua would not be a barrier for most students in the HEI. Moreover, with consideration of teachers’ composition and available teaching resources, Chinese would be the most economical language to use as the medium of instruction. Setting Tibetan, the community language in the local society, as a compulsory subject was the most optimal solution, since it would not only consolidate the status of Tibetan in the HEI, but also avoid the communication problems that would arise from Tibetan instruction in class.

With regard to English, although it is the most popular foreign academic language worldwide for most students, it is unrealistic to be used as the medium of instruction in the HEI. However, as a common compulsory course for all of the enrolled students, it has received much attention in the explicit policy. The class hours allocated to English were much longer than those for Chinese and Tibetan. This policy orientation helps confirm the status of English in the academic setting of the HEI. Even though it is not the instructional language nor the community language, the vitality of English was safeguarded by the quadrupled class hours.

A multilingual HEI always faces the challenge of setting the appropriate instructional language and choosing suitable languages as subjects for their students. A rational and sustainable language policy not only needs to ensure the learning effects but also needs to guide students to show due respect for multilingualism. In this sense, the merits of the present LEP in the HEI cannot be denied.

6.3. Language for Academic Learning and Language for Social Life

A HEI is a miniature society, in which students need to manage their study as well as their social lives on campus. Thus, the sustainability of the language policy in the HEI not only rests upon the languages used in the classroom, but also on the ones used outside the classroom in students’ campus lives.

The results regarding students’ language practices in and out of the classroom give an insight into the ecology of the LEP in the HEI. Among the six major stages of language education policies identified by the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) [

22], the multilingual LEP implemented in the HEI in Tibet now seems to be set at Stage 5, in which the Tibetan language and culture have been granted certain rights to be maintained and developed, but its academic function has not been widely accepted by the majority. In the classroom domain, Chinese was still the dominant language for course instruction, learning materials, and exams, so its educational function was irreplaceable. This may well be due to the broader academic environment in China, in which the major educational activities in the mainstream higher institutions are all organized in Chinese [

23]. Thus, adopting Chinese as the primary language for learning is perhaps the most feasible and economical way of organizing education in an HEI in Tibet, as learning resources in Chinese are abundant nationwide [

24]. It would be hard for an HEI in Tibet to develop such a wide range of—and equally high quality of—learning resources in Tibetan by their own efforts. Although Tibetan language was set as a compulsory course for all of the students in the HEI, students’ Tibetan language proficiency could not impact their learning achievement to the degree that Chinese can. This is also true for English, the academic influence of which cannot work in that location at full capacity even though it is the most commonly used academic language worldwide. Without appropriate social and functional supports, the academic position of English would be difficult to establish in the HEI.

On the other hand, languages used outside the classroom showed a diversity. Contrary to Chinese domination, Tibetan and Chinese were both used frequently by students for social interaction. There was obvious increased use of Tibetan language, especially in students’ leisure times. Indeed, many campus services were bilingual in Chinese and Tibetan. Notices and announcements, campus broadcasts and celebration parties were mostly offered in Chinese and Tibetan. It was clear that both Chinese and Tibetan can be found to have a solid foundation in students’ social lives. However, in the social domain, not being a national language nor a community language, English was seldom used. This, in a certain sense, conveys a message that, in order to promote and sustain the status of English in the HEI, perhaps more work is needed to expand its social functions in the campus life.

6.4. Initial Literacy and Exit Requirement

To facilitate and sustain the learning of multiple languages among students in an HEI, a multilingual program with rational admittance criteria and outcome goals is indispensable. Through the questionnaire, it was found that, for the three major languages taught in this HEI, stratified teaching was adopted according to students’ initial language proficiency. Students were grouped into classes of different language levels based on their scores in the college entrance examination. High, intermediate and low-level classes were set to meet the needs of various students. As we can see, students’ Tibetan language proficiency differed sharply at the time they entered the HEI; some may have spoken Tibetan as mother-tongue and may have learnt Tibetan literacy for more than ten years, while others may not have ever come into contact with it before. The large discrepancy that existed in the initial literacy made it impractical to set a single standard to evaluate all of the students’ language achievements. Streaming is perhaps the most feasible way for Tibetan language education. For the low-level class, the requirement is to pass the Tibetan language proficiency test band one, which only demands that students grasp around 500 words and cope with some simple communications in real life. For the beginners, this is an introductory course that helps them master some preliminary knowledge of Tibetan. However, the high-level class requires students to pass the Tibetan language proficiency test band four, which means that students have to have an advanced ability in listening and speaking, and at the same time acquire a stronger ability in reading ancient and modern Tibetan, as well as a good ability in writing it. This sets a challenging goal for those Tibetan students who have already mastered the basic language skills of Tibetan. Passing the appropriate Tibetan language proficiency test was set as a must for graduation. This move, undoubtedly, established the important position of the Tibetan language in the HEI, and sustained students’ commitment to learn it.

Streaming was also applied to the courses of Chinese and English, in the process of which initial literacy was also a major concern, since, to a certain extent, it may influence the effectiveness and acceptability of the course content, which in turn further influences whether the particular course can be sustainable in the context. By stratifying students into different levels according to their entrance examination scores, the Chinese and English classes can better serve the needs of the students with various language abilities. On the other hand, an appropriate exit requirement is also crucial. Evaluating students by different criteria helped students recognize the value of being multilingual in the HEI. It created a climate in which linguistic diversity was valued. Setting attainable and challenging goals for students can usually facilitate them to put in more efforts in their learning and thus ensure the sustainable development of multilingualism in the HEI. In the case of English in the HEI, it simply proved that the lack of certain exit requirements may demotivate students to work hard on English, despite the long class hours. To promote the vitality of English on campus, perhaps the HEI could consider setting personalized but definite exit requirements for students with varying English language abilities.

Generally, by examining the LEP in the HEI from an ecological perspective, we found that a corporative image centered around Chinese was created for multilingualism. The coexistence of multiple languages—Chinese, Tibetan and English—was encouraged and promoted among students both in and out of class.

7. Conclusions

Following Spolsky’s [

6] theory of the ecology of language policy, the present study analyzed the sustainability of the LEP in a typical HEI located in Tibet. It was found that Chinese, Tibetan and English were all valued and respected in the explicit policy, which guaranteed that all three languages were granted a position in the formal curriculum and thus set the general tone for the LEP in the HEI. Although Chinese, as the medium of instruction, occupied a dominant position in the academic domain, outside the classroom Tibetan was also frequently used by students in their campus lives. The findings revealed that the academic function of language in the HEI was mainly undertaken by Chinese, while the social function was equally shouldered by Chinese and Tibetan. Comparatively, the status of English was weak due to a range of situational and operational factors. Nevertheless, a cooperative environment was created by a series of internal and external stakeholders in the HEI.

A number of theoretical and practical implications can be derived from the study. Theoretically, the study tested the ecological framework of language policy in the context of a minority HEI in China, which proved that—apart from the explicit preferential policy as manifested by the curriculum—the language practice in and outside the classroom was equally important for the sustainability of the LEP in a HEI. Practically, the findings suggested that stratified teaching for students with different linguistic backgrounds is a good way to implement language education in a minority HEI. Considering students’ initial literacy level and setting different exit criteria may be a more humanized and effective way to evaluate students’ learning achievement and thus better facilitate their learning motivation. Furthermore, the findings also implied that, in order to ensure the sustainability of a multilingual policy, measures should be taken to expand either the academic or the social functions of the languages. Helping students to recognize their linguistic needs in the long run may make their learning passions more sustainable.

The findings of this study are not only instructive for the formulation of multilingual language policies in HEIs in Tibet, but also have enlightening values for HEIs in other minority areas in China and abroad. It is hoped that, by developing a sustainable multilingual program at the higher education level in minority areas, the quality of higher education for minorities will be significantly strengthened and empowered.