1. Introduction

Tourism is considered to be one of the most important drivers of wealth and economic growth [

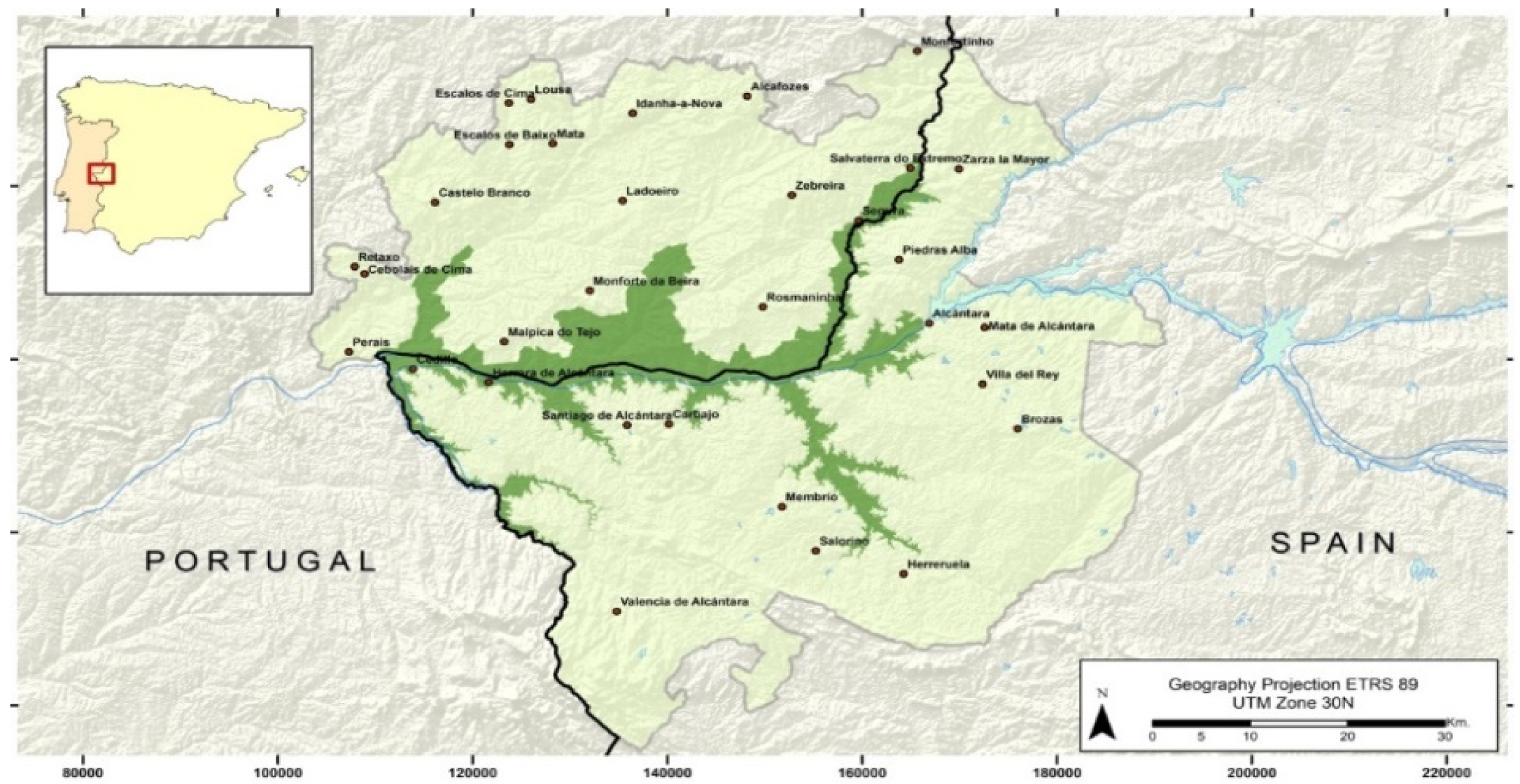

1]. The benefits are especially obvious in destinations that have barely enough financial resources to survive. An example of this is the International Tagus Natural Park, in the Extremadura region of Spain (

Figure 1). It was given its name in Decree 187/2005 [

2].

The International Tagus National Park was declared a Portuguese national park on 18 August 2000 [

3]. In 2012, Spain and Portugal signed a cooperation agreement with the aim of managing its two sections, which were separated by the border. Four years later, because of its excellent natural environment, it was designated as a Transboundary Biosphere Reserve.

The park’s outstanding natural resources contrast sharply with its economy. In 2017, the gross domestic product per capita (GDPpc) in the park was the lowest in Spain–EUR 16.981 per inhabitant, compared with the Spanish average of EUR 27.558. In the same year, average personal earnings (PIBpc) in Portugal were EUR 19.209, and EUR 13.100 in the villages belonging to the park [

4]. High unemployment rates and job instability characterise the territories on both sides of the border. These negative features have accelerated the decline in population in Extremadura in relative terms (with an inter-annual variation rate of −0.8% for 2016–2017) [

5]. The lack of economic resources provides a framework for a study of Tagus International Park. Tourism will be crucial in the economic growth of Extremadura and Alentejo [

6].

Tourist activities have been seen as one of the major sources of the host´s supplementary income [

7], especially the “host and guest” exchange [

8]. According to Blau [

9], host and guest interaction provides both parties with significant resources, which can only be provided when there is such interaction. It is therefore important to analyse how the actors involved influence social cohesion, to explain cooperative behaviour [

10], and to examine the psychological factors that might positively transform residents’ attitudes towards tourist activity [

11,

12,

13].

In attempts to improve the social and economic conditions of impoverished regions, the relationship between host and guest has been widely discussed from the guest´s perspective [

14]. However, little attention has been paid to the host´s point of view [

15,

16,

17,

18] nor to the impact of touristic host and guest relations in general [

19].

The present study investigates the contribution made by the host and guest exchange to the host´s social and economic welfare in respect of reciprocal behaviour and social reciprocity, and the influence these have on both the host and guest´s standard of living. It is hoped that it will help in the formulation of long-term strategies for the destinations in question [

20].

4. Results

A structural equation model (SEM) was used to explain how the host perceives tourist activity in the International Tagus Natural Park. This method is convenient when observable variables or indicators measured by latent variables are related [

73]. This approach is based on structural equation modelling to visually examine the relationships between unobservable or latent variables such as the conveyed in the hypotheses [

74]. As was noted above, it is recommended for social science analysis is predictive accuracy, which means that the model could be replicated in other scenarios [

74]. According to Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt [

72], reliability and validity should be examined.

PLS path modelling is a well-established method for analysing structural equations. It has been used by various researchers in organisation and business management and tourism [

73,

75,

76,

77]. It first determines the estimation of the measurement model and second, the structural model [

78]. This technique is less rigid concerning minimum requirements on sample size and the nature of the scales of measurement compared with other methods based on covariances [

72]. To structure the data, SmartPLS software version 3.2.3 was used [

78].

4.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

The measurement model, employing only reflective measures, yielded satisfactory results after deleting the item TPP1. Its original value was 0.663 < 0.7 [

79], so it was deleted. After running the model again, all items loaded as expected and were significant at the

p < 0.05 level (

Table 5).

The evaluation of the measurement model is shown in

Table 6. According to Chin [

80], the model is considered acceptable if the loads are greater than 0.5. Fornell and Larcker [

81] establish the values of the composite reliability through the extracted mean variance (AVE). It should exceed the recommended limits of 0.7 and 0.5, as is demonstrated.

In accordance with Fornell and Larcker [

81], the discriminant validity and the Heterotrait-Monotrait method were analysed [

82]. The first indicator evaluated the discriminant validity through the comparison between the square root of each AVE on the diagonal and the correlation coefficients. The values of the diagonal were higher than rows and columns, and therefore the discriminant validity was approved. In relation to the second Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) indicator, values obtained should be less than 0.90 [

83], so they were accepted (

Table 7).

Table 8 shows the effect size values (f

2). Values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 were considered small, medium and large [

71]. These indicate a good overall fit for the model.

4.2. Analysis of the Structural Model

Once the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model was confirmed, the relations between constructs were tested, by obtaining the different statistical parameters using the bootstrapping method (5000 sub-samples). Support for the hypotheses was based on the sign, the value and the significance of the t-values in each of the path coefficients (β) [

74]. As we can see in

Table 9, the hypotheses were significant.

According to Chin [

80] R

2 values were described as 0.67, 0.33 and 0.19 and as substantial, moderate and weak, respectively. The inner path model was described as substantial (R

2 = 77.5). It meant that SEW was substantially explained by the three exogenous variables: RB, SR and TPP.

The predictive relevance of dependent constructs was also significant. It was obtained by calculating the value of Q

2 (cross-validated redundancy index) through “blindfolding” [

84]. Q

2 (SEW = 0.334) > 0, so the model had predictive capacity (

Table 10) [

85]. To complete the analysis of the structural model, the goodness-of-fit was calculated from the goodness-of-fit (GoF) indicator from the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) proposed by Hu and Bentler [

86]. In our case, the value of SRMR was 0.63, which was below the 0.08 recommended by Henseler et al. [

85], so it can be said that the model had a good quality.

5. Discussion

This research analysed the influence of host and guest social exchanges on the communities’ social and economic welfare at the International Tagus Natural Park. The underprivileged natural territory contains communities with earnings under the average in Spain and Portugal. This situation has persuaded hosts to find ways of supplementing their incomes to improve their socioeconomic welfare.

Based on 194 hosts´ questionnaires in 18 villages, a model was presented. It shows that reciprocal behaviour (RB) and social reciprocity (SR), as well as the touristic participative plan (TPP), have become powerful tools to open up the economically underprivileged territory to new visitors. Its substantial explanatory capacity (R

2 = 77.5%) conveyed the fact that host and guest social exchange has become a crucial way of increasing the social and economic welfare of the community. As a result, tourism has become an important element in helping to ensure the economic growth of Extremadura and Alentejo, which was one of the aims of the present study [

6]. The hosts considered tourist activity as one of the major sources of supplementary income [

7]. The results also showed that the participative programme amongst hosts, who proposed and designed the items, was central in attaining the high significance of the model presented. Similarly, the predictive capacity of the dependent variable SEW was also high (Q

2 = 0.461). These are convincing reasons why the model should be applied to international parks with similar socioeconomic conditions.

Significantly, all the hypotheses were confirmed; reciprocal behaviour (RB) between hosts and guests (RB → SEW: β = 0.362; t = 3.575) and social reciprocity (SR→SEW: β = 0.344; t = 3.449) positively influenced the community´s socioeconomic welfare. According to Sinkovics and Penz [

31], social contact between guests and hosts is essential in developing territories if the latter are to increase their standard of living. That reciprocity affects both guest intention to return and host satisfaction [

30]. The results showed that social exchange theory encourages the interaction between the parties (host and guest) as a way to implement a cost-benefit analysis.

The results also revealed that, in low income territories, reciprocal behaviour (RB) and social reciprocity (SR) optimise the guests’ and hosts´ mutual benefits and social relationship by providing socioeconomic reasons to guide these relationships [

33]. As a result, the host´s experiences, values, attitudes and behaviour are considered relevant as a way of promoting the touristic encounter, which helps to upgrade that deprived territory. In other words, from the survey it can be deduced that the costs of the host and guest relationship are lower than the rewards the settled community receive from guests. Efforts are reciprocated within the park.

Table 11 shows that host and guest relationships in the Portuguese municipalities promote that reciprocity more than Spanish ones because those areas are less economically developed [

6]. Supplemented incomes are needed relatively more in the Portuguese territories, so there is a greater need for them to develop their economies. Portuguese hosts consider their traditional values as of assistance in providing a high-quality service to guests (9.4) as well as in fulfilling their touristic obligations (9.3). As Eusebio, Kastenholz and Breda [

87] highlight the relevance of the traditional values to provide a professional service to guest. That touristic service amongst tourism stakeholders such as visitors, public and private agents of products and services and hosts are measured according to their behaviour, satisfaction, host–guest interaction and perceptions of the tourism phenomenon and its implications on the villages’ development. Residents are very pleased with tourism in the village, and are willing to attract more visitors and encourage the emergence of new tourist activities. They tend to view tourism as a positive activity that has contributed to the revitalisation of the village, therefore being in favour of tourism development. Residents suggest the creation of recreational activities as well as the improvement of commercial and other services to make tourists stay longer.

As

Table 11 indicates, on the Spanish side, hosts are especially committed to fulfilling their professional obligations (8.5) and their involvement in touristic activities and local authority planning (8.4). That engagement is well explained by Canoves, Villarino, Priestley and Blanco [

88]. There is a need to sustain population levels in Spanish rural areas in the face of rapid depopulation. The new rural economy was based on family businesses and, as in the rest of Europe, constituted a strategy for the diversification of farm and economic activities. The strategy for the survival of small family farms has been focused on specialising in new products, or providing complementary touristic activities. At this stage the engagement has been mainly promoted by the female members of the family who welcomed the guests into rural homes, promoted the values of the local culture and organised food and accommodation [

89].

Therefore, host and guest integration in this developing territory is not only positive but also affirms that their mutual commitments [

20,

45] are balanced in terms of costs and benefits for the community [

89].

A tourist participative plan not only positively affects the host´s socioeconomic welfare (TPP → SEW: β = 0.331; t = 3.169) but also mediates its effect on the reciprocal behaviour between host and guest (TPP →RB: β = 0.509; t = 6.928) as well as their social relationship (TPP →SR: β = 0.372; t = 3.370). Even though the participative plan is applied to the Spanish side only, data show that hosts are willing to work on a participative plan scenario by contributing to surveys to improve local tourism [

10,

61].

There are grounds to say that tourism at the International Park responds to hosts’ expectations by promoting social exchange between host and guest despite the social and economic uncertainty and the seasonality of the occupation.

6. Conclusions

According to Ap [

33], the main reason to initiate the host and guest exchange, from the resident’s point of view, is the improvement of the social and economic well-being of the community. Host perceptions and attitudes are predictors of behaviour towards tourism in host–guest exchanges in the tourism sector. As the most impoverished region in Spain and Portugal, the International Tagus Natural Park has recently designed a pilot tourist strategy not only to improve hosts’ social and economic welfare but also to promote the outstanding natural and touristic resources of the area, such as travelling by ship along the Tagus River, visiting local villages with castles, dolmens, necropolises, roman granite tombs and historical ruins, birdwatching and visiting the environmental interpretation centre and the Roman Bridge (2nd century BC) in Santiago de Alcántara, as well as other tourist hotspots and natural resources.

However, in contrast to other studies [

69], economic uncertainty in this destination has added a new positive perspective in the social exchange theory. Touristic aspects such as the perception of tourists saturating the towns, the lack of preservation of local traditions [

44] and the negative touristic and environmental impact on welfare have been appropriately balanced by the actions of the community at the park [

84]. Here, a tourist-related plan has been appropriately organised and managed according to the host expectations [

84].

Hosts at this impoverished site are found to be engaged with tourism development, not only improving the level of resident hospitality [

47] based on respectful attitudes towards visitors, but also changing their attitudes towards encounters with guests, who respond reciprocally and positively to this behaviour [

46]. It is also worth noting the high level of acceptance amongst hosts of new strategies designed to enhance tourism through participative decision-making [

42,

59] and the involvement of the locals in the process [

55]. Such findings may help to formulate long-term strategic theories in these destinations [

20].

The differences in perspective between Spanish and Portuguese hosts should be pointed out. Whereas the economic view of tourism is highly ranked amongst Spanish hosts, social exchange is highly valued by the Portuguese locals. This is because visitor numbers are lower in the western part of the park. Social exchange may therefore be seen as the best way to sustain tourism in the area.

Overall, the positive host and guest relationship in the park has decisively helped the community to develop economically and socially, turning the loss of population into job opportunities in every municipal territory [

5]. It has improved the quality of life [

10].

The present study has a number of limitations. It is a pilot project, and there is no prior evidence with which to compare the results. No similar research has ever been carried out in any of Spain’s seventeen regions. Second, the regional authorities were not cooperative; a response from those quarters would have enriched the discussion. Future research might compare the host, guest and local and regional authorities’ responses to the social exchange theory. Third, even though the touristic participative plans added a new dimension to decision making, they did not include the potentially adverse socio-cultural and environmental effects of unsustainable practices in such underprivileged territories. The objectives of sustainable tourism were not addressed when the long-term strategic decisions were being designed. Fourth, the collaborative planning between host and guest omitted an explanation of the main challenges the territory faced. Finally, some key issues were absent from the tourist participative programme. They were: measuring the host and guest´s level of motivation in providing solutions for a socioeconomic “upgrade” of the territory; a readiness on the part of all parties (local and regional government, hosts, guests and so on) to work towards implementing plans proposed by the local authorities; the level of hosts’ commitment to future tourist programmes; and clear lines of responsibility for stakeholders.

Future research will include a study that, in accordance with social exchange theory, compares the host and guest involvement in upgrading the territory with the local and regional authorities’ attitudes towards providing solutions. Second, the host and guest´s prosocial behaviour will be examined to ascertain their level of agreement on the decisions arising from the participative pilot programme. In accordance with Schwartz [

39], host and guest attitudes, norms, responsibilities and behaviour will be analysed. Using Schwartz´s theory [

90], personal beliefs, moral obligation and behaviour could be linked as part of the effort to improve the park region’s economic status [

91].