1. Introduction

Environmental psychology refers to an area of psychology whose subject of research is the interrelationship between the physical environment and human behavior and experience. It is important to emphasize the reciprocal aspect of this relationship, since it is not only the physical scenarios that have an impact on people’s behavior, but it is also that individuals have an active influence on environments [

1]. Environmental psychology is an area of studies that has emerged from academia, and its focus is mainly the present time, local contexts and levels of analysis, and environmental and psychosocial dimensions [

2]. In relation to this, Hidalgo [

3] mentioned that the work carried out in the field of environmental psychology contributed and provided solutions, increasing human well-being through the analysis of the interrelation of people with the environment (natural and/or built) that surrounds them.

Furthermore, explaining people’s behavior towards the environment is one of the vital issues in environmental psychology, which has many applications in addition to theoretical ones [

4,

5]. Environmental behavior is defined as a type of behavior that implies avoiding even the smallest damage to the environment. From a conceptual point of view, environmental behaviors are a set of environmental actions carried out by individuals in the community towards the environment which encompass a wide range of emotions, tendencies, and specific prerequisites for behavior [

6]. Conceptually similar work has also been carried out by Kals [

7], who found that affective factors such as feelings of guilt, indignation at insufficient conservation of nature and interest in nature can provoke ecological behavior.

Nowadays, environmental problems represent a serious threat to life on Earth. They manifest as global climate change, degradation and depredation of natural resources, species going extinct, violence, socioeconomic crises, and endless social and ecological disturbances. Given that most environmental crises have been caused by human behavior, it is required to seek knowledge about what predisposes people to behave in a sustainable manner. According to Aragonés et al. [

8], concern about the environment should be related to the way in which the human being is understood in relation to nature: Either from an anthropocentric perspective, that is, as the center of the environmental discourse; or from ecocentric positions, where the human being is one more member of the ecological niche where life unfolds.

Consequently, several research works have turned to the study of various psychological and social factors related to the environment, naming them in different fashions. On one hand, Corral et al. [

9] discussed affective and cognitive proenvironmental predispositions, as well as proecological and prosocial actions (sustainable behaviors). According to the model proposed by the authors, for the psychological dimensions of sustainability, it is required to have simultaneous presence of affective states and cognitive factors that, in conjunction, would stimulate the appearance of sustainable behaviors or actions. This data, along with results from other previous studies, have demonstrated the pertinence of this construct, orientation to sustainability as an integrator of predispositions (both cognitive and affective), and actions directed towards caring for the environment, both physical and social.

This type of predispositions could be confused with an environmental attitude, because attitudes influence behavior; however, according to Suárez [

10] people do not always behave in accordance with a disposition or intention to behave pro-environmentally, mostly because of contextual and attitudinal variables that may determine the action to follow. In relation to this, Hernández, and Hidalgo [

11] mentioned that behavioral intention indicates a willingness to act in a certain way regarding the object of attitude. Beliefs and environmental behavior are not part of the attitude, although there is a relationship between them. Moreover, environmental attitude has been defined as "the favorable or unfavorable feelings towards some characteristic of the physical environment or towards a problem related to it" [

1] (p. 115), the concept proposed here considers actions in favor of both the physical and social environment in addition to the feelings (emotions), for which it will be differentiated with the term predispositions towards sustainability.

Furthermore, other studies have determined that an orientation towards sustainability would be characterized by an inclination to enjoy contact with nature, which becomes manifest by reporting positive emotions that emerge after such a contact. This supports the findings of Kals [

7], who observed that this orientation induces the preservation of the environment [

12].

Finally, as mentioned by Mayer and Frantz [

13] (p. 503), efforts in environmental research have sailed away from having a specific and localized focus to pursue a broader reconceptualization of the relationship with nature, such as cultural values, how concern about nature might rise through empathy, and how the natural environment determines our identity. Additionally, according to the results of Jiménez-Domínguez and López-Aguilar [

14], research carried out in Mexico has shown that well-defined social and place identity facilitates the anchoring of more sustainable practices and habits. According to Uzzell et al. [

15], this social identity describes the socialization of a person with the physical world, in which processes of identification, cohesion and satisfaction are involved. Hence, we propose a new construct: psychosocial predispositions towards sustainability (emotions, environmental actions, and socioenvironmental actions), for the purpose of identifying the relationship that might exist between said predispositions and environmental identity in a sample of university students.

1.1. Psychosocial Predispositions Towards Sustainability

As mentioned before, Corral et al. [

16] have suggested the existence of a series of predispositions that allow for the appreciation of the diversity and interdependence of the relationships between people and environment, as well as the adoption of lifestyles that guarantee the sustainability of socio-ecological systems for present and future generations. Because of this, it is important to consider these predispositions, since a person that has them will prefer to voluntarily act in favor of the environment with a proecological and prosocial objective, which would imply that his or her care for the environment relies on sustainability reasons, rather than coercion, customs, or monetary reinforcement.

Moreover, as mentioned by environmental psychology, the scenarios that surround and sustain our daily lives have a major influence in the way we think, feel, and behave [

1]. Thus, we will conceptualize our study variables considering three factors: emotions, environmental actions, and socioenvironmental actions.

1.2. Emotions

1.2.1. Affinity Towards Diversity

According to Corral et al. [

16], this factor reflects a liking for the biological, physical, and social varieties with which the individual comes into contact. This dimension has a notorious affective component that covers a fundamental pillar of Ecology: the conservation of diversity. Similarly, Corral et al. [

9] mention that appreciation for physical and social diversity relates to care for the environment, as well as other psychological dimensions of sustainability such as altruism, deliberation, austerity, and proecological behavior, among others. Affinity Towards Diversity, according to Corraliza and Bethelmy [

17], is defined as the tendency to appreciate the dynamic variable of the interactions between human beings and nature in everyday situations within a socio-bio-physical environment.

1.2.2. Feelings of Resentment for Ecological Deterioration

This variable points out the emotional reactions caused by witnessing behaviors of destruction, pollution, wasting of resources, and damage caused to people. These reactions, along with guilt and outrage caused by insufficient environmental protection, are part of a factor that Kals [

7] calls emotional affinity towards nature, which is characterized by attributions and evaluations of responsibility that are related to behaviors of environmental protection [

12,

16].

1.2.3. Appreciation of Nature

This last affective dimension represents a liking for contact with plants, animals, and non-built environment. This factor reflects pleasant emotions such as happiness, pleasantness, wellness, and positive spirits, when exposed to environments that present characteristics of nature or that are natural [

16]. Exposure to nature, as literature points out, not only has restorative effects on physical health, emotional wellness, attention, and performance of cognitive duties, but also generates a state of emotional affinity that may translate into care for and action in favor of the environment.

1.3. Emotional Actions

1.3.1. Perception of Environmental Norms

This psychological dimension of sustainability alludes to how much people consider that other individuals accept and support behaviors of care or destruction of the environment. According to Sevillano and Olivos [

18], social norms refer to people’s beliefs about the appropriate form of behavior (common and socially accepted) in a specific situation. Environmental research has traditionally focused on the personal norms of individuals and not so much on social ones, finding that people who develop a personal norm or personal obligation to care for the environment will behave in an environmental way. Accordingly, if an individual perceives that environmental preservation is positively valued in his or her social group, this becomes the personal norm; on the other hand, if environmental depredation behaviors are seen as virtues, then the individual will tend to behave in an exploitative manner with the environment [

19]. Having said that, Corral et al. [

16] consider that this perception indirectly signals the presence of agreements, rules, or prescriptions that govern sustainable behavior.

1.3.2. Self-Presentation

Self-presentation refers to the attempt of controlling information about the self that is presented to a social audience whether in real or imagined situations. According to Corral et al. [

16], if the values of a community approve of the convenience on maintaining environmental integrity, it is very likely that individuals will try to present themselves as responsible people, but, on the contrary, if normative context prioritizes opposite values, then that presentation of the self will be more oriented towards communicating consumerist or resource-predatory characteristics [

19].

1.3.3. Deliberation

Deliberation is a crucial component in sustainable behavior because it is defined as behavior intentionally directed towards taking care of the environment. Furthermore, it is identified as perseverance, defined as the intentional continuation or reapplication of an effort to achieve a goal despite the temptation to abandon it; it also relates to the purpose of life and self-determination [

20] (p. 122). Corral and Pinheiro [

21] also state that deliberation implies that this caring behavior must be produced while having the purpose or specific intention of bringing about human wellness and the preservation of other organisms, objects, and situations in the environment.

1.4. Socio-Environmental Actions

1.4.1. Equity

Equity is the action through which the individual comes into contact with people who have different conditions (ethnicity; age; sexual, religious, or political orientation; among others) and is related to behaviors of fair treatment and distribution of resources without bias, meaning not to give some people more than others based on their condition [

22]. Equity also implies a balance between human wellness and ecosystem integrity, allowing people to access resources and preserve physical environment. Equity is defined as justice according to the law or natural right and relates to the allocation of power and wellness. Social equity is usually evaluated by considering the distribution of resources or the access that people have to them [

23].

1.4.2. Altruism

This variable has been considered as a set of actions aimed at vulnerable groups and it is presented as behaviors of selfless assistance towards others; for example, giving economic aid to other people, donating material and time resources to social benefit projects, or participating in voluntary activities in favor of the general population. Importantly, altruism is deliberate; altruists behave with the intention to help others and the knowledge that, with this behavior, they will deprive themselves of some benefit, be it time, money, a material possession, or even a bodily one (in the case of organ donation). According to Corral [

23], altruism is a fundamental component in the motivation that originates and upholds the actions that protect the environment. Most researchers also agree that both altruistic motivations and actions are required to maintain the quality of the environment in order to prevent environmental degradation.

1.4.3. Proenvironmental Behavior

Proenvironmental behavior has been analyzed as a general behavior or a more or less specific behavior (e.g., saving water, recycling, or environmental activism) [

24,

25]. Proenvironmental behaviors are defined as the intentional, effective actions that correspond to social and individual demands and that result in the preservation of the physical environment [

23]. Li et al. [

26] mention that proenvironmental behavior can reduce a negative impact on the environment, these behaviors can be summarized in three main environmental behaviors: waste reduction, reuse and recycling. Examples of these behaviors include reutilization, recycling, composting, control of solid waste, purchasing ecologic products, conserving water, saving energy, reducing the use of automobiles, discussing environmental topics, persuading others to act pro-ecologically, proenvironmental lobbying, and family planning. With the aim of evaluating proenvironmental behaviors, a variety of instruments, such as self-report surveys and registers of environment-friendly actions have been created and validated by means of a set of behaviors. The advantages of using these self-evaluation reports include their high reliability and the possibility to evaluate a large number of behaviors [

23].

1.4.4. Environmental Identity

Identity is a central psychological construction, a way of describing an individual that places it within a political and social context. It has become a more and more prominent topic in psychology over time, and one with clear relevance to environmental attitudes and behaviors [

27]. Identity is, fundamentally, a way of defining, describing, and localizing the self. Considering the environmental matter, Clayton [

28] (p. 45) argued that people can develop a specific environmental identity: “a sense of connection with some part of the non-human natural environment that has an influence in the way we perceive and act in the world; the belief that the environment is important for us and a part of who we are”.

1.5. Objective

The purpose of this study was to test a model of relationships between psychosocial predispositions towards sustainability (emotions, environmental actions, and socio-environmental actions), as a second order factor, with environmental identity in a sample of university students.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We analyzed the responses of 417 undergraduate students of 6 universities located in 2 cities in northwestern Mexico: Hermosillo, in the center-north (

N = 283, corresponding to 67.9%) and Ciudad Obregón, in the south (

N = 134, 32.1%). The students were randomly selected from social sciences and engineering majors. Participants were 17 years old or older (M = 20.61, SD = 4.31), with 57% (236) female and 43% (181) male students. Most of the participants were single (96.4% single, 3.1% married, 0.2% divorced, and 0.2 common-law union). The sample was selected in a representative manner using the Decision Analyst STATS

TM version 2.0 program, considering the total university population of the state of Sonora according to the most recent report of the Secretaryship of Public education [

29]. The total population of university students is 109,309, for the determination of the sample size, 5% points of maximum acceptable error were considered, the estimated percentage level of 50% with a desired confidence level of 95%, resulting in 383 participants as the main sample; however, 40 more students were considered in case there was a need to eliminate cases.

2.2. Instruments

Next, we describe the scales that were used in this study for measuring psychosocial predispositions:

Affinity Towards Diversity (ATD) was measured with 4 items from the scale proposed by Corral et al. [

9]. These items manifest a presence or “liking” for the existence of diversity or differences of political orientation, ethnicity, or social class, among others. The answer was chosen in a scale from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (fully applies to me). The Feelings of Resentment for Ecological Deterioration (FRED) [

30], that consider emotional reactions of disgust (0 = I am indifferent, 5 = I feel so bad I would try to avoid it at all costs (stop the person from doing it)) to situations of damage to the environment were measured with 4 items. Another scale that was present was Appreciation of Nature (AON) [

16], which is constituted by 4 items. This instrument includes a self-report survey of positive emotions resulting from contact with nature, which are evaluated from 0 (does not apply to me) to 3 (fully applies to me).

To measure Perception of Environmental Norms (PEN) [

12], there were 4 items that had the objective to measure how good or bad participants believed that people in their locality consider a series of environmental interactions are. Responses ranged from 0 (very bad) to 4 (very good). Meanwhile, Self-Presentation (SPR) [

12], consisting of 7 items in Likert scale, contained answers related to social actions or ideals that were seen as very bad (0) to very good (4) and alluded to behaviors such as saving energy, reusing, or pro-ecological consumption. To measure Deliberation (DEL) [

30], we used 6 items with a scale to determine how frequently people are willing to participate or become involved in actions to protect the environment or care for resources. Answers ranged from 0 (I would never do it) to 3 (I would be willing to do it always).

Equity (EQT) was measured with a scale developed by Corral et al. [

31] and included 4 items containing sentences that proposed equity between sexes, ages, socioeconomic conditions, ethnicities, and others, with options ranging from 0 (fully disagree) to 4 (fully agree). Actions related to Altruism (ALT) [

31], described four behaviors of selfless assistance (meaning, without seeking reciprocity) to other people or charity institutions. Response options in this scale ranged from never (0) to always (3). Additionally, items in the scale to measure Proenvironmental Behavior (PEB) [

26] reported how frequent the behaviors of saving energy, reutilization, recycling, conserving water, monitoring others’ environmental behaviors, reliable use of products, search of environmental information, use of environmental-friendly products, etc., were. This scale contained values from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Finally, the Environmental Identity (EI) [

32] scale was also applied, which consisted of 4 Likert-type items ranging from 0 (heavily disagree) to 5 (heavily agree) and measured aspects such as scope and importance of individual interactions with nature, how nature contributes to the group the individual identifies with, agreement with a proenvironmental ideology associated with the group, and level of enjoyment and pleasure obtained from nature. The scale was adapted to Spanish using bidirectional translation.

2.3. Procedure

The instruments were applied in a group manner in the university classrooms where the students attended their classes. The general objective of the research was explained to them and they were invited to participate voluntarily. The ethical considerations involved in the study (respect, beneficence, justice, and confidentiality) were also indicated in the instructions of the instrument. Students were also given a space in which they indicated their agreement to participate, thus providing their informed consent. All of the students in this sample voluntarily participated in the study. This research and all of its procedures were subjected to a monitoring process executed by a doctoral thesis committee, composed of five member, who at all times supervised and validated not only the methodological structure, theoretical relevance, and scientific pertinence of this investigation, but also, the criteria and regulations established by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sonora (CEI-UNISON), which adheres to the normative framework of the National Bioethics Commission (CONBIOÉTICA, Mexico). The time used to answer the questionnaires ranged from 25 to 35 min.

2.4. Data Analysis

Results were obtained via univariate statistics (mean, standard deviation, maximum and minimum scores). In addition, internal consistency of the scales was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha, using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21, and relations between the latent variables were estimated with a structural equations model, with EQS 6.1. Two important steps were considered to make this estimation: the measurement model and the structural model. The measurement model is a confirmatory factor analysis, while the structural analysis estimates the relationships between the factors obtained in the measurement model. With the measurement models, the 10 first-order factors were built: (1) Affinity Towards Diversity, (2) Feelings of Resentment for Ecological Deterioration, (3) Appreciation of Nature, (4) Perception of Environmental Norms, (5) Self-Presentation, (6) Deliberation, (7) Equity, (8) Altruism, (9) Proenvironmental Behavior, and (10) Environmental Identity. Factors 1, 2, and 3 were the indicators of a second order variable called “Emotions”; while 4, 5, and 6 were factors to the variable “Environmental Actions”; and 7, 8, and 9 were constituents of the “Socio-Environmental Actions” variable. The relationships between these three second order variables would subsequently conform a latent third order variable called “Psychosocial Predispositions Towards Sustainability”, these relationships between the constructs were tested first by means of Pearson correlations and later by structural equation models (SEMs). Finally, we specified a model of structural equations in order to demonstrate that these factors, Predispositions and Environmental Identity, were significantly interrelated.

2.5. Results

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and internal consistency of the scales that were used. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranges between 0.63 and 0.85, which indicates an acceptable to high reliability of the instruments. As for scales, items in the Equity category presented the highest scores (mean = 2.71, with a range of answers from 0 to 4, α = 0.73), followed by Affinity Towards Diversity (mean = 2.71, range 0 to 3, α = 0.68) and Appreciation of Nature (mean = 2.53, range 0 to 3, α = 0.83). Meanwhile, Environmental Actions presented central scores, this includes Perception of Environmental Norms (mean = 3.46, range 0 to 4, α = 0.63), Deliberation of Actions of Environmental Care (mean = 2.34, range 0 to 3, α = 0.85), and Self-Presentation (mean = 3.24, range 0 to 4, α = 0.77). The scales with lowest scores were Feelings of Resentment for Ecological Deterioration (mean = 3.27, range 0 to 5, α = 0.79), Proenvironmental Behavior (mean = 1.85, range 0 to 3, α = 0.83), and finally, Altruism (mean = 1.31, range 0 to 3, α = 0.77).

The correlations between the scales that make up each second-order factor are shown in

Table 2. Significant interrelations are observed between the constituent variables of psychosocial predispositions towards sustainability, as well as between these variables with environmental identity.

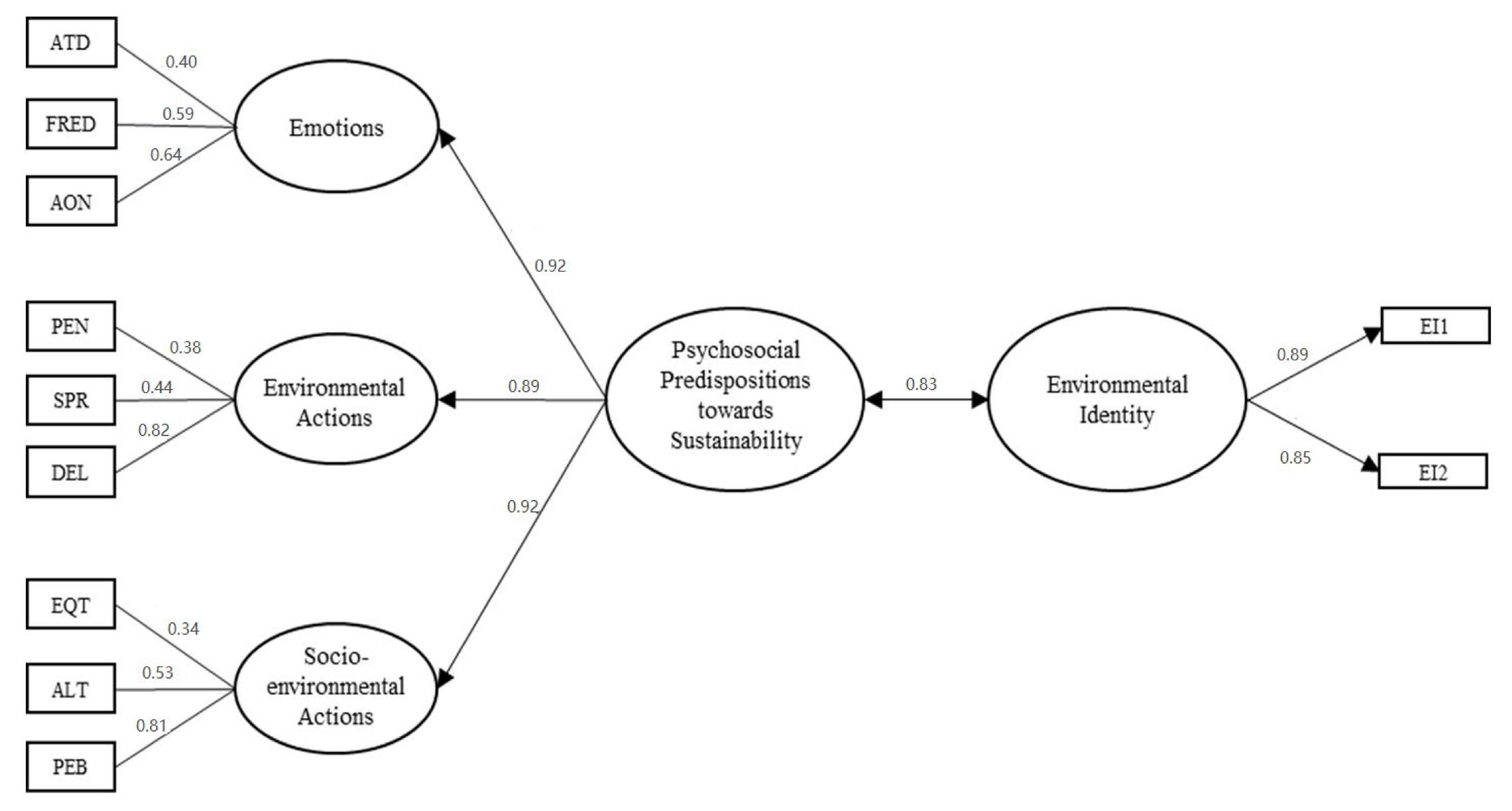

Similarly,

Figure 1 shows the results of the Psychosocial Predispositions towards Sustainability model obtained via structural equation modeling procedures, where first order factors coherently emerge from their indicators, as is revealed by their high and significant factorial loads (

p < 0.05). Likewise, second order constructs are built on the correlations between the first order factors that also generate high and significant lambda values. Factorial loads were, in the case of Emotions, 0.40 for Affinity Towards Diversity, 0.56 for Feelings of Resentment for Ecological Deterioration, and 0.64 for Appreciation of Nature; in the case of Environmental Actions, factorial weights were 0.38 for Perception of Environmental Norms, 0.44 for Self-Presentation, and 0.82 for Deliberation; and finally, in Socio-Environmental Actions, the factorial weights were 0.34 for Equity, 0.53 for Altruism and 0.81 for Proenvironmental Behavior.

Furthermore, the figure shows that Psychosocial Predispositions towards Sustainability coherently emerge from the significant interrelations between its three factors by having high and significant factorial weights (0.92 for Emotions, 0.89 for Environmental Actions, and 0.92 for Socio-Environmental Actions). Finally, the structural coefficient going from the Psychosocial Predispositions towards Sustainability to the Environmental Identity, and vice versa, has a value of 0.83 and is statistically significant (p < 0.05). Wellness-of-fit indicators include values of x2 (117.712, 39 df, p < 0.05), NNFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.07, which indicate that the data fits the model. The R2 value of this relationship model is 0.69, which reveals that Psychosocial Predispositions towards Sustainability are 69% related to Environmental Identity.

3. Discussion

One of the purposes of this study was to test the relationships between emotions, environmental actions, and socio-environmental actions by identifying the pertinence between them and conforming a higher-order factor, which was named Psychosocial Predispositions towards Sustainability. The consideration of this terminology is owed to the fact that Corral [

19] mentions that those who are in favor of sustainability show certain characteristics of personal nature that incorporate inclinations (dispositions) or psychological states without disregarding the existence of situational factors, such as the existence of social ideals towards caring for the environment. For instance, Li et al. [

26] mention that proenvironmental behavior has received increasing attention, questions about the main factors that induce people to adopt pro-environmental behavior have increasingly occupied the interests of researchers in different academic fields.

According to this, Corral [

33] says that the requirements of caring for the environment are as important as the skills to tend to those requirements by pointing to dispositional variables that orient individuals to act in a proecological manner. The model that is proposed in this research has been replicated in several studies [

9,

16,

34]; nevertheless, the contents of the items in some of the variables were adjusted for the population at which they were aimed, which is also the reason why there was a need to modify the name of the construct itself.

In addition, results from this study are realistic in the sense that they interrelate factors that are bound both logically and theoretically with schemes of pro-sustainable life, which guide actions of care for the socio-physical environment and generate tendencies to behave in a prosocial, proecological manner [

16]. In addition, people’s environmental actions become visible to others, which would facilitate their dissemination; this is what Ro et al. [

35] called social diffusion in their research, this concept refers to the formation of sustainable habits that arises through imitation and repeated actions when an individual sees another performing pro-environmental behavior. Same as in previous studies, these findings point to a correspondence of data with theory by revealing that the people that become involved in actions of care for the physical environment also look after the social environment. This is backed by how emotions connect with intentions and actions in favor of the environment.

Regarding the identification of the interrelation between predispositions and environmental identity, it was found that the strength of the relationship between these two variables is very high (0.83), as well as its explanatory power (69%). In relation to this, Dutcher et al. [

36] express that human beings that feel a fundamental equality between them and the natural world (as well as other people) experience more empathy and compassion for nature. Likewise, Clayton [

28] proposes that environmental identity is part of the elements with which people configure their self-conceptualization, a sense of connection with the natural environment, based on history, emotional ties, and similarity, that affects the ways in which the individual perceives and interacts with the world. The natural environment is associated with strong emotional and social experiences, which is why it is likely that the time spent int natural environments is well remembered and helpful in satisfying the need for belonging [

27].

In relation to this, Porras-Contreras, and Pérez-Mesa [

37] consider it important for environmental psychology to positively consolidate the processes of construction of environmental identity from the affective connection with the natural environment. In this way, when analyzing the relationship between environmental identity and students’ predispositions, it gives an idea of how an affective or emotional state can help in identifying with the natural environment. This idea could be supported by Clayton et al. [

38] (p. 86), “environmental identity is an important concept, because it is related to environmentally sustainable behavior, it affects our well-being and influences decision-making”.

Similarly, Freed [

39] proposed that environmental identity can help explain environmental actions and pro-environmental behaviors in which individuals choose to participate, this meaning that action, choice and behavior are part of environmental identity. Behaviors and identities can influence each other in a complex and dialogical way. The relationship is reciprocal, behaviors can influence identity and identity can influence behavior [

40].

Finally, and relating to what was previously said, the subject of study of Environmental Psychology is the effect that human behavior has on the environment and vice versa, in the way that there is always an interaction between the person and its environment, the former and the latter affect each other mutually [

41].

In this way, with the results of this research we can conclude how people are interconnected to the environment by inferring that the actions that they perform in favor of the latter would guarantee its preservation in both present and future times, which is one of the objectives of sustainable development. Moreover, sustainable development considers some of the variables that were studied in this research; and, in accordance with the Centre for Environment Education [

42], the principle of equity between present and future generations would account for the use of environmental, economic, and social resources. It would also consider it to be a dynamic and evolving concept, with multiple dimensions (like the ones considered in the tested model), and subject to a variety of interpretations that tend towards the vision of a different world that constitutes humanity’s biggest challenge for the new century.

Withal, most of the studies tend to treat individual psychological factors as variables to analyze their impact on proenvironmental behavior, likewise the causes of this behavior have changed with the complexity of the social and psychological determinants of actions towards the environment. Further, the remnants of sustainability have caught up with psychology demanding a commitment from it to address environmental and quality of life issues in combination. Environmental psychology can contribute to this effort with methods and models that evaluate how a sustainable lifestyle could influence human well-being without degrading the environment.

These results are in line with previous studies, as has already been specified, as well as the use of the same measurement scales; however, due to the population to which this research was directed, changes were made in the wording and content of the study. In addition to not considering all the variables that have been studied before. That is why the findings in this research may have more practical implications, especially because identifying factors that stimulate behavior for caring for the environment is crucial for the generation of intervention programs or strategies at different levels (academic, political, and social). In relation to this, Ramkisssonn et al. [

43] indicated that environmental behavior provides a high level of attachment and a higher quality of life, highlighting the positive impact of environmental behavior on people’s lives.

Finally, as analyzed in the present investigation, the relevance of psychology lies in the identification of the causes of the behaviors that affect the environment, their degree of impact and the identification of more effective intervention strategies. Despite being a new and consolidated discipline, Environmental Psychology continues to develop. Many are the topics that it addresses; however, the limit of the study of these has not been reached, since new variables appear every day that can be incorporated into the studies that have already been carried out, or in which develop today.