Abstract

Korean duty-free shops sales rank first among duty-free shops around the world (Generation Research, 2018) and have become a target of interest for academics and industry observers. In particular, attention has been focused on variables affecting the shopping behavior of this fast-growing segment of online duty-free shop users. In this research, the main variables of the technology innovation acceptance model and the target-oriented behavior model are added. Focus is placed on the decomposed theory of planned behavior, and the variables affecting the behavioral intention are identified. A survey is conducted with users of online duty-free shops (Internet, mobile) as targets, and an analysis of the structural equation model is utilized. Among the technology innovation acceptance variables, the factors affecting attitude are compatibility and perceived usefulness. It is determined that only perceived behavioral control has a significant effect on behavioral intention, which is a dependent variable of the decomposed theory of planned behavior, and the attitude and subjective norms are found to have a significant effect on both desire and behavioral intention. Thus, it is confirmed that attitude is a key variable in explaining this research model. This research has academic implications because it examines variables affecting the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users by integrating the theory of technology innovation acceptance and the decomposed theory of planned behavior, with the addition of a desire variable. Moreover, there are practical implications in that online duty-free shop operators have provided meaningful basic data to establish differentiated marketing strategies from offline duty-free shops with the goal of expanding use. The results of this study are expected to serve as basic data for increasing the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users and promoting the sustainable development of online duty-free shops in South Korea.

1. Introduction

The global duty-free industry has grown rapidly due to socio-economic impacts such as increases in the number of travelers, the development of tourism industries, and the growing trend of spending in developing countries. Since the initiation of aviation liberalization, the number of tourists departing from South Korea has greatly increased, and the Ministry of Justice’s Incheon Airport Immigration Office has announced that the number of passengers using Incheon Airport has increased every year since the opening of Incheon Airport.

Continued increases are expected globally based on projections for socio-economic factors such as continental economic growth, the per capita expenditure of travelers, tax exemption benefit levels, consumer consumption propensity, and each country’s duty-free industrial policies. In particular, the duty-free market share in the Asia-Pacific region has increased by about five times over the past ten years and is expected to continue to increase in the future. With the development of technologies in line with the trend for greater levels of mobile shopping, the online duty-free shop market has become a market that cannot be overlooked. Because the purchase patterns of duty-free shop users are rapidly moving from offline channels to online and mobile channels, more online channels are being activated. Younger age groups with strong consumption patterns tend to gravitate toward online channels, since they consist in a commerce transaction through the Internet, providing high accessibility and various economic benefits. Due to these changes, sales in online duty-free shop purchasing channels are increasing. The duty-free shop industry is increasing sales by capturing customers’ hearts through direct marketing through SNS channels and selling them at online duty-free shops. Duty-free shop users are rapidly changing because of their strong pursuit of luxury and individualization at the level of purchase, and their preferences are also diverse [1].

In line with this trend, duty-free shop marketers are feeling the urgent need to predict the shopping propensity and behaviors of online duty-free shop users. To provide optimal services to customers, the need for research on usability has become more important. The consumers’ behavior goes through a perceptual and evaluative goal-setting process for the product and decides whether to accept it or not according to the expectations regarding the result, which is a goal-oriented behavior [2,3]. It is necessary to predict the behavior of online duty-free shop users through desire, which is the main variable of the goal-oriented behavior model.

Online duty-free shops are a new type of purchasing channel and are different from general purchasing decisions because there is a great deal of uncertainty about products and services. In this respect, in order to understand the decision-making process of users regarding online duty-free shops, a study applying innovation-acceptance variables is needed.

It is necessary for online duty-free shop operators to pursue customer-based competitive advantages by identifying important factors affecting the behavioral intention of customers to use online duty-free shops. Duty-free shopping is expected to become an important shopping behavior for domestic consumers, and the growth potential of online duty-free shops is also expected to be very high. Therefore, it is now time to understand the perception and behavioral intention of customers toward online duty-free shops. Recently, studies on online duty-free shops have focused on researching differences in shopping behavior based on consumer characteristics [4,5,6,7]. In these studies, it has been pointed out that future research on customer needs and customer acceptance factors would be beneficial. Nevertheless, a systematic understanding via academic efforts to investigate online duty-free shop users has thus far been lacking. Accordingly, the present study aims to determine why customers continue to shop in online duty-free shops. To be more specific, it endeavors to determine in detail the influence of individual belief variables centered on the decomposed theory of planned behavior, which is an acceptance model for information technology. It does so by employing an on-going behavioral intention analysis (rather than only looking at acceptance aspects) for users of the rapidly growing online duty-free shopping phenomena (i.e., Internet duty-free shops and mobile application duty-free shops). By exploring and constructing an explanatory model to understand the process of accepting online duty-free shops, this paper seeks utilization methods to increase the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users and suggests implications for activating online duty-free shops. It also derives practical implications to continuously improve sales.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Online Duty Free

Online duty-free shops are similar to Internet shopping malls in that they operate in a virtual space. However, the goods must be received directly at the airport. Online duty-free shops are free to sell goods without time and space constraints, as long as the users can gain access to them using their devices. In addition, unlike offline duty-free shops, the number of promotions is relatively high, so users enjoy economic benefits. Recently, this shopping experience has been expanded beyond traditional Internet-based platforms to mobile duty-free shopping apps, which has increased the utilization rate of online duty-free shops. Nevertheless, disadvantages exist. For example, online shopping does not translate into greater product diversity, and online payment transactions carry inherent risks for the seller. In South Korea, duty-free shops are currently providing users with access and shopping experiences through both offline and online channels.

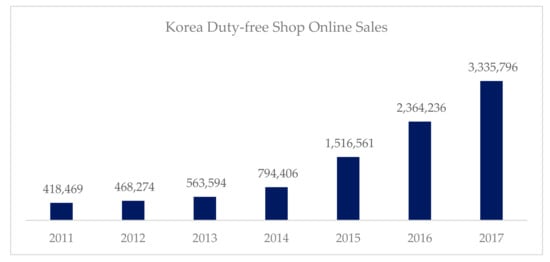

The first Internet duty-free shop site opened in 2000. In 2012, a duty-free shop mobile app was launched and operated to facilitate greater ease and affordability, a move that was in line with the smart era. Online duty-free shops are also on the rise, as more and more users seek to make reasonable purchases due to the prolonged global recession. Online duty-free shop sales are included in downtown duty-free shop sales, and as of 2015, the market share increased to 1.4 trillion won, occupying a market share of 16%. The growth rate of online duty-free shops compared to offline duty-free shops is significant (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Korea Duty-free Shop Online Sales (2011~2019). Note: Unit KRW million. Data: South Korea’s online duty-free term analysis report. Source: South Korea Customs Service, Korea Duty Free Shops Association [8].

2.2. Extended or Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) proposed by [9,10] analyzed the belief structure affecting behavioral intention as a single structure. According to the majority of previous studies, although the theory of planned behavior proved to be a suitable theory for predicting behavior, it is unsuitable to explain the influence of specific belief variables [11]. Accordingly, to better understand the relationship between belief structures that affect behavioral intention and other preceding variables, many studies have attempted to approach beliefs with multidimensional structures [12]. Taylor and Todd [12] argued that the decomposed theory of planned behavior was best suited for the purpose of understanding factors that affect behavior rather than expectations. The decomposed theory of planned behavior revised the beliefs affecting the use of information technology in the theory of planned behavior proposed by [9,10], and it analyzed them in a multi-dimensional structure by modifying and specifically breaking down the technology acceptance model (TAM) and innovation diffusion theory (IDT) [12,13]. This provided a systematic understanding of the determinants of information technology use [13]. The advantage of this theory is that it can take a closer look at the influence of specific beliefs and shape the resulting strategy accordingly. Moreover, in the case of a single dimension, when the explanatory power is unstable, it can be stabilized via decomposition [14,15]. Accordingly, in this study, the decomposed theory of planned behavior is applied to predict the shopping behavior of online duty-free shop users. Taylor and Todd [13] suggested that the theory of planned Behavior (TPB) is an appropriate model for behavioral analysis that adopts new technology products. Hansen and Stubbe [16] also proved that rational the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and TPB are suitable models for predicting consumers’ purchasing behavior on the Internet, and it proved that TPB is a model with higher explanatory power for purchase intention and behavior than TRA.

The attitude beliefs in the decomposed theory of planned behavior are perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and compatibility based on TAM and IDT [12,13]. Moon and Kim [17] looked at this relationship by adding perceived enjoyment as an element of attitude belief, while Tornatzky and Klein [18] verified that relative benefits and compatibility were variables that significantly affected attitude. Accordingly, in this research, attitude is composed of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, which are the technology belief variables of the technology acceptance model, perceived enjoyment of the augmented technology acceptance model, and compatibility of the innovation diffusion theory. Perceived ease of use is the expectation of the degree of effort exerted by an individual toward a particular system [19]. Reductions in the effort required to operate a system can lead to a more and more regular use of that system, leading to improved performance [19,20]. In this research, perceived ease of use is defined as the extent to which one believes that the use of online duty-free shops can be conveniently accessed, and that the method and process of use are easy, simple, and not difficult to understand. Davis [19] proposed that perceived ease of use in TAM was a variable for forming positive emotions in the attitude toward the acceptance of new technologies. Perceived enjoyment is said to be a degree of enjoyable recognition, excluding performance results from the use of a particular system [21]. Lu et al. [22] asserted that perceived enjoyment was an enjoyable degree excluding performance results related to the use of an instant message. It has also been defined as the degree to which pleasure values (intrinsic motivation) derived from enjoyment and excitement are obtained through information stimulated by online shopping [23]. In other words, the perceived enjoyment of technology can be conceptualized as the pleasure value of technology [24]. The inherent motivation for Internet use, the online shopping situation, and the state of self-awareness related to ultimate enjoyment are successfully applied and manipulated in TAM [25]. Perceived enjoyment in the present study is the extent to which one enjoys the experience without clinging to the results, even if one is not good at using online duty-free shops. Perceived usefulness is a variable that is used as an essential factor in technology related research and affects acceptance intention. It is the degree of a consumer’s belief that the use of the Internet and smartphones will improve the performance of duty-free shopping. It is the degree to which one believes that there will be relatively more promotional benefits such as price saving if one uses online rather than offline duty-free shops. In the present study, perceived usefulness is defined as the extent to which one believes that the use of Internet and smartphones in online duty-free shops will provide the expected benefits. Lin and Lu [26] revealed that perceived usefulness had a positive (+) effect on attitude, a result that was also found in earlier studies [13,27]. Compatibility describes the agreement between innovation and the overall lifestyle of the user [28]. In other words, by accepting innovative technology, compatibility is the degree to which one has the skills to accept the technology or to have a similar work style. Accordingly, in this research, compatibility is the degree to which the use of online duty-free shops is similar to one’s usage patterns. If the acceptance of a new technology is similar to one’s own style of work, the person is more likely to perceive it as useful [18]. On the basis of the literature review, this study formulates the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Perceived ease of use has a positive influence on perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Perceived ease of use has a positive influence on attitude.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Perceived ease of use has a positive influence on perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Perceived usefulness has a positive influence on attitude.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Perceived enjoyment has a positive influence on attitude.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Compatibility has a positive influence on attitude.

Hansen and Stubbe [16] explained the importance of attitude in relation to the behavioral intention of consumers who purchase groceries online, by applying the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the theory of planned behavior (TPB). The relationship between factors that affect the intention of using Internet banking based on the decomposed theory of planned behavior affects subjective norms and attitudes about information technology [12,29,30]. Al-Somali et al. [31] verified that there was a social influence on the acceptance of online banking. Subjective norms refer to the perceived pressure of an individual with the universal idea that most people should or should not carry out certain actions [32]. In other words, if an important neighbor or group that affects an individual believes that it is necessary to use information technology, the individual will also use it. In the field of information technology, this concept was mainly interpreted as a belief in information technology, and it proved to be an important determinant affecting the acceptance and use of information technology in many fields related to information systems [33,34]. As factors affecting subjective norms, which are the main variables of belief, groups are subdivided into those with internal effects and those with external effects [12,35]. The internal group is divided into friends, family, and workplace (e.g., colleagues and supervisors), and the external group is divided into media and mass media [12,36]. Accordingly, in this research, groups are divided into internal and external groups, and like the research results provided by Ajzen and Fishbein [37] and Rogers [38], it was judged that the groups affect the acceptance of technology depending on the social environment.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Interpersonal influence has a positive influence on subjective norms.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

External influence has a positive influence on subjective norms.

Venkatesh [21] selected perceived behavioral control as the main variable, together with the self-efficacy of Bandura [39], which was based on the social cognitive theory as well as facilitating conditions. Perceived behavioral control is determined by control belief, which takes two aspects into consideration [9,10]. Control belief is divided into three components: self-efficacy, which is the construct that is most similar to perceived behavioral control; technology facilitating conditions, which exist on an external level; and resource facilitating conditions. In previous studies, self-efficacy was included in subjective norms. In this research, perceived behavioral control is explained based on Taylor and Todd [13], who first presented the decomposed theory of planned behavior.

Self-efficacy is a motivation factor to perform one’s work, and it is the confidence in one’s ability in terms of internal resources [9,10,40]. It denotes an individual’s belief to perform successfully one’s own internal resources, such as behavioral, cognitive, and emotional resources. It can be structured through subdivision into cognitive beliefs and technology-accepting beliefs, and it can reveal the relationship with behavioral intention [13]. In this research, self-efficacy is the demonstration of one’s ability in an unpredictable situation and is defined as the ability to solve problems without great difficulty while using online duty-free shops. Parthasarathy and Bhattacherjee [41] stated that external influence, interpersonal influence, perceived usefulness, and service utilization determined whether online services were used. According to Murphy [42], people with low self-efficacy when using a particular system have low confidence in the ability to use the system and tend to accept the information as it is when it is presented. On the other hand, people with high self-efficacy are said to have high confidence in the ability to use the system because they think and act efficiently and actively [43].

Facilitating conditions are variables that are claimed to have a direct effect on the use of the system, which could be economic resources such as time and money or social surroundings. Thomson et al. [44] explained that facilitating conditions provided help to users in the use of PCs, and Chang and Cheung [45] also confirmed that they were variables that significantly affected the use of the Internet. In other words, Taylor and Todd [12] regarded them as a special resource necessary for performing behavior and divided them into technology facilitating conditions and resource facilitating conditions to reveal the relationship between information technology compatibility and facilitating conditions. Kim et al. [11] stated that the facilitating condition was the degree to which potential adopters held economic resources and actually made subjective judgments about whether time and resources could be invested. Freeman [46] pointed out that when web servers suffered from slow connection speeds and frequent failures, this negatively affected the user, and the interest and motivation to learn was thereby reduced. Bergeron et al. [47] stated that users perceived it to be easy if their environment could help, even if they were new to information technology or unfamiliar with it. The prerequisite for using an online duty-free shop is a shopping activity conducted on an online channel, so the user must have a basic computer or smartphone and be able to utilize it. Furthermore, if the user has difficulty using an online duty-free shop, there should be people around to help. As in these previous studies, it was assumed that resources and abilities play an important role in controlling one’s behavior when using online duty-free shops. Therefore, the following hypotheses were established:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Self-efficacy has a positive influence on perceived behavioral control.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Facilitating conditions have a positive influence on perceived behavioral control.

According to Bandura [48], many consumer behaviors are characterized by goal-orientation. Duty-free shops are places where time and space are limited. They are mainly used by consumers with clear target settings. Consumers’ innovation characteristics can be derived by adding desire that reflects the unique characteristics of duty-free shops to the decomposed theory of planned behavior [49]. In many previous studies, external motivations such as goal-oriented behavior (e.g., time savings or cost savings) or intangible benefits (e.g., free shopping, access to detailed product information, and the availability of multiple product choices) are related to purchase intention [50,51]. Existing empirical evidence based on usefulness instead of extrinsic motivation factors indicates that there is a positive impact on online shopping intention [52]. Goal-directed behavior was found in various fields. In this study, the factors of goal seeking were included in the Decomposed TPB and the attitude-behavior relationship was expanded and explained in detail [53]. Unlike users who use offline stores, those who use online stores have unique characteristics. Online shoppers spend more time browsing through many online websites to buy what they want [54].

Desire is a major predictor of behavioral intention, which further increases behavioral intention by mediating attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, and contains strong motivational factors that trigger behavior [55,56,57]. Desire is a concept necessary to form a behavioral intention, and it is a stimulator that induces behavior based on attitudes. If desire is not formed, the idea of achieving a goal is not strongly formed [58]. In this research, desire is a psychological motivation necessary to induce the intention to use duty-free shops and is a strong emotional situation for target behavior. Before using the duty-free shop, consumers hope that their shopping needs will be satisfied. The following hypotheses are formulated based on a literature review.

Hypothesis 9a (H9a).

Attitude has a positive influence on desire.

Hypothesis 9b (H9b).

Attitude has a positive influence on behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 10a (H10a).

Subjective norms have a positive influence on desire.

Hypothesis 10b (H10b).

Subjective norms have a positive influence on behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 11a (H11a).

Perceived behavioral control has a positive influence on desire.

Hypothesis 11b (H11b).

Perceived behavioral control has a positive influence on behavioral intention.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Desire has a positive influence on behavioral intention.

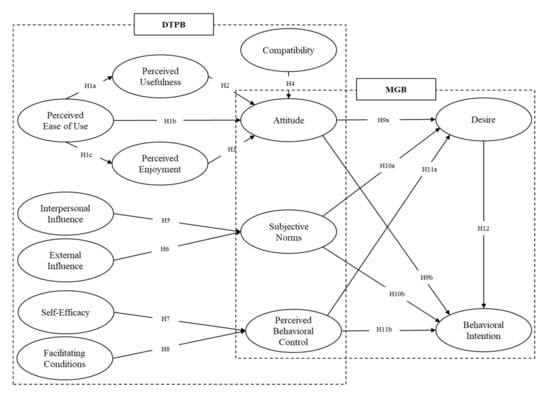

2.3. Research Model

The research model used in this study predicts the behavior of online duty-free shop users by grafting a technology acceptance model on the basis of the decomposed theory of planned behavior. Based on previous studies, the hypothesis is set to influence attitude by selecting perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived enjoyment, and compatibility, which are the main variables of the technology acceptance model. Relative benefits and complexity were considered as constructs similar to perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use and were excluded from this research model [59]. To verify the influence of individual belief variables, we divided them into internal and external influence variables and examined their effects on subjective norms. We then attempted to determine how self-efficacy and facilitating conditions affect perceived behavior. The following research model has been established to analyze the structural relationship of the decomposed theory of planned behavior in online duty-free shopping (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed Conceptual Model.

3. Methodology

The present survey is based on measurement items presented in the preceding studies to reveal the relationship between the consumer disposition of duty-free shop users and shopping value and behavioral intention. As such, we selected as research targets shoppers who had had experience using an online duty-free shop in the previous year. Consumers with active smartphones and strong technological innovations have switched their shopping channels from offline duty-free shops (downtown and airport duty-free shops) to online duty-free shops (internet, mobile). It was judged that the analysis of users of online duty-free shops with strong innovation could provide various implications for the acceptance of innovative online duty-free shops. After briefly explaining the survey to the respondents, the self-management method was used, and samples were extracted using the convenient sampling method. The sampling of this research was conducted with users who had experience in using an online duty-free shop, i.e., an Internet duty-free shop or mobile application for 18 days from 18 November to 5 December 2015. The offline questionnaire survey was advantageous in collecting various opinions because it faced the respondents directly. Of the 450 copies distributed, 344 copies were collected, showing a response rate of about 76%. 314 copies were analyzed, while 30 copies that lacked responses or were judged to have poor integrity were discarded.

Aside from the demographic characteristics, all items in the questionnaire were answered using a Likert 7-point scale. The measurement variables and measurement items used in this research are shown in Table 1. The items used in this study were used by revising and supplementing the measurement tools adopted in the decomposed TPB and goal-directed behavior model [58,60,61,62,63].

Table 1.

Survey Questionnaire and Sources.

In terms of the gender distribution of duty-free shop users, there were 226 women (72.0%) and 88 men (28.0%). It was found that women had much more experience using duty-free shops than men. According to consumer psychology analyst Underhill [73], genetically, men have a hunter’s temperament and women have a collector’s temperament, so he insisted that women had a more significant attachment to shopping. In terms of age distribution, there were 132 people in their 30s (42.0%), 119 people in their 20s (37.9%), 50 people in their 40s (15.9%), nine people in their 50s (2.9%), and four people in their 20s (1.3%). Those in their 20∼30s accounted for more than 80% of the total. In terms of monthly income, it turned out that 64 respondents (20.4%) earned less than 2 million won, 111 respondents (35.4%) earned 2.01 to 2.99 million won, 81 respondents (25.8%) earned 3.01 to 3.99 million won, 31 respondents (9.9%) earned 4.01 to 4.99 million won, 15 respondents (4.8%) earned 5.01 to 5.99 million won, and 12 respondents (3.8%) earned more than 6 million won (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Respondents.

This study, to identify characteristics of passengers who have experience using airline social media, analyzed data using the SPSS 21.0 program and the AMOS 20.0 program, that have been widely used as statistical packages in social sciences. The frequency analysis was conducted to identify the characteristics of the sample, and confirmatory factor analysis was performed to further analyze the validity of the measurement model. The secondary forms of concepts that are composed of sub-factors were each analyzed by confirming factor analysis to verify the internal validity and then converted to the primary form. In addition, Using Cronbach’s α, by scales, the refinement of the scale was carried out. The concentration and discriminant validity were verified, and the hypothesis of this study model was verified through structural equations.

4. Empirical Analysis

As a result of conducting a confirmatory factor analysis to confirm the reliability and validity of the measurement items used in this research, the squared multiple correlation (SMC) and standardized regression coefficient values for subjective norms (1), facilitating conditions (2), desire (3), and desire (4) items turned out to be less than 0.4 and 0.5, respectively. They were thus removed. Subsequently, as a result of assessing the compatibility for the constructs of the remaining items, some indices did not meet the acceptance level, but all indices except for the RMSEA index of all variables turned out to satisfy the recommended level, so this research model was judged to have a good fit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of Unidimensional Model Fit.

As a result of the measurement model analysis, it turned out that CMIN/DF = 2.025, RMR = 0.064, GFI = 0.777, AGFI = 0.737, NFI = 0.888, RFI = 0.874, IFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.932, CFI = 0.940, and RMSEA = 0.057. The number of samples was relatively small compared to the number of variables, so the GFI and AGFI were slightly lower than the reference values. On the other hand, other indices were found to be in line with the standard, so the model compatibility index was excellent, and the proposed model of this research was acceptable. The SMC values of all variables were higher than 0.5, exceeding the reference value (SMC = 0.4), and the latent variable explained the variance of the measured variables fairly well. In addition, the critical ratio (CR) was greater than ±1.96, which was acceptable without removing additional items, and the variance extraction index of each concept was 0.5 or higher. Convergence validity was secured. Moreover, because the reliability of each concept was 0.7 or higher, the reliability and convergence validity were satisfied. The Cronbach’s α to evaluate internal consistency and the standardized regression coefficient value were also higher than 0.7, so the reliability of the items was high. Overall, it could be seen that the reliability and validity of the constructs for the observed variables, including the observed variables used in this research, were secured (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

It was confirmed that the average variance extraction index of the construct difference was higher than the correlation coefficient squared value, thereby ensuring discriminant validity (Table 5). However, the partial discriminant validity was shown to be attitude and perceived usefulness, behavioral intention and perceived usefulness, and self-efficacy and facilitating conditions. In the relationship between perceived behavioral control and facilitating conditions, it was found to be 0.692, and discriminant validity was not secured. Accordingly, an additional test was carried out comparing the constrained and unconstrained models. As a result of the analysis, in the relationship between perceived behavioral control and facilitating conditions, no discriminant validity was found, since, as it turned out, the constrained model estimation value χ2 (14) = 32.174, and the non-constrained model estimation value χ2 (13) = 29.909, and between these two concepts, Δdf = 1, Δχ2 = 2.265, there was only a non-significant difference (p < 0.05). The facilitating condition can be seen as a source of perceived behavioral control, so it was considered to have a high correlation. In the relationship between attitude and perceived usefulness, discriminant validity was secured, since, as it turned out, the constrained model estimation value χ2 (19) = 41.871, and the non-constrained model estimation value χ2 (18) = 32.934, and between these two concepts, Δdf = 1, Δχ2 = 8.937, the gap exceeded the standard criteria of discriminant validity, 3.84. In the relationship between behavioral intention and perceived usefulness, discriminant validity was secured, since, as it turned out, the constrained model estimation value χ2 (19) = 50.084, and the non-constrained model estimation value χ2 (18) = 35.571, and between these two concepts, Δdf = 1, Δχ2 = 14.513, the gap exceeded the standard criteria of discriminant validity, 3.84. In the relationship between self-efficacy and facilitating conditions, discriminant validity was secured, since the constrained model estimation value χ2 (14) = 49.418, and the non-constrained model estimation value χ2 (13) = 83.664, and these two concepts turned out to be Δdf = 1, Δχ2 = 5.754. As we have seen above, the discriminant validity between the latent variables used in the research model was tested using all methods.

Table 5.

Results of Correlation Analysis.

The model fit turned out to be as follows: χ2 = 2732.955 df = 1046, p = 0.000, GFI = 0.727, AGFI = 0.693, RMR = 0.46, CFI = 0.9, TLI = 0.893, and RMSEA = 0.07. The value of CMIN/DF turned out to be 2.613, which was less than the reference value (3), showing a result that satisfied the overall fitness. Accordingly, the compatibility for the model proposed in this research was secured. While the GFI value, which is the explanatory power index of the data for this research model, was lower than the acceptance level, the RMR value was close to 0, which could be judged to be a suitable model. It was important to evaluate the overall conformity of the model, but an evaluation of the conformity of the proposed model to the basic model could not be excluded. Both the TLI and NFI values appeared to be approximately 0.9, so it could be said to be a suitable model overall. Although not all of the results of the fit index were above the acceptance level, it was determined that the overall level was good and that there was no difficulty in carrying out the hypothesis test.

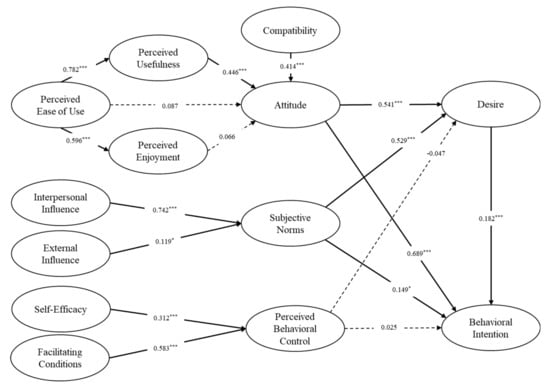

The hypothesis test results of this research model, which were proposed by adding the variables of perceived enjoyment and desire to the decomposed theory of planned behavior, are shown in the following Table 6 and Figure 3. As causal variables affecting attitude, only compatibility and perceived usefulness were found to have a significant effect on the relationship between compatibility, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, and perceived enjoyment. This indicated that attitude changed depending on the degree of compatibility and usefulness with one’s self. Perceived ease of use was significant within 1% of the significance level to perceived usefulness with β = 0.782 and CR = 11.973. H1a was supported and had a significant effect on perceived enjoyment with β = 0.596 and CR = 11.847.

Table 6.

Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Structural Model.

Figure 3.

Test Results of the Proposed Model. Notes: (1) a The amount of variance explained. (2) * p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. (3) Numbers in parentheses are the standardized path coefficients.

As a result of examining the relationship between the internal and external influences as a leading factor in subjective norms, it was found that all of them had a statistically significant effect. In particular, the impact of the internal influence on subjective norms was greater than the external influence, and the explanatory power was 64.6%. H7 and H8, which asserted that self-efficacy and facilitating conditions (i.e., the decomposition of perceived behavioral control) would affect perceived behavioral control, were supported. It was confirmed that attitude and subjective norms affected desire, playing a key role in emotional factors. The factors influencing behavioral intention, the most important determinant of behavior, turned out to be in the order of attitude, desire, and subjective norms. Among them, attitude had the greatest influence on behavioral intention. This indicated that attitude was an important factor in explaining behavioral intention. As such, the explanatory power of behavioral intention was about 70.1%, and the explanatory power of the structural model was high. In the case of online and offline duty-free shop users, desire played the biggest role in behavioral intention, whereas for online duty-free shop users, attitude played an important role. Perceived behavioral control was found to have a non-significant effect on both desire and behavioral intention. In summary, H1a, H1c, H2, H4, H5, H6b, H7, H8, H9a, H9b, H10a, H10b, and H12 were supported, and H1b, H3, H11a, and H11b were not supported. The research hypothesis test results are shown in the following figure, and the specific statistical values are shown in Table 6.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we decomposed the theory of planned behavior as the basis of our research and differentiated it by adding the elements of belief in technology acceptance and the elements of emotion that play a key role in emotional factors. Existing previous studies did not consider cognitive, emotional, or technical factors in an integrated manner. Therefore, we approach the decision-making process of online duty-free shop users from the perspective of technology acceptance to facilitate an understanding of their behavioral intention.

The results of the empirical analysis can be summarized as follows. First, we focused on which factors affected the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users. In this study, as in the research of Song et al. [74], attitudes were found to have the greatest influence on behavioral intentions, rather than subjective norms and desire. In other words, if the reaction to the online duty-free shop is favorable, you can easily make a decision to use it in the future. Shih [75] revealed that individual consumers’ attitudes toward Internet shopping are closely related to consumer acceptance. It was also confirmed that internal influences, like family and friends, are more influenced by subjective norms than external influences such as the mass media. Therefore, as in the research of Rogers [38] and Fry et al. [76], in the theory of innovation diffusion, subjective norms were important as a factor in the adoption of innovation and as a major influencing desire. If the response to an online duty-free shop is favorable, it is easy to make a decision to use it again in the future. It was also confirmed that internal influences such as family members and friends were more influential in subjective norms than external influences such as mass media. In other words, it was found that the online duty-free shop users were affected by their circumstances, and people around them played an important role in their behavior. As in previous studies, self-efficacy and facilitating conditions had a positive effect on perceived behavioral control. The abilities of online duty-free shop users and given facilitating conditions are helpful in behavioral control, which also affects their behavioral intention.

Unlike with offline purchasing channels, it is difficult with online purchasing channels to make a purchase while simultaneously experiencing the products one wants to purchase. In a study by Jung & Yoon [77], it was found that attitudes and subjective norms influence purchase intentions in order, and perceived behavioral control did not have a significant effect.

The feeling of desire stimulates the users based on psychological factors. In the case of online duty-free shops, it seems that there is a limit to the psychological stimulation one experiences through a screen, which is why the desire is not so strong. The attitude of cognitive factors and subjective norms was found to have a significant effect on desire. As in the results of Taylor et al. [56] and Song et al. [74], it was found that attitude has a significant effect on desire. The more favorable attitudes of online duty-free shop users are formed, the greater their desire to purchase duty-free products. Therefore, online duty-free store operators need psychological stimulation by continuously providing services that can highlight the advantages of online duty-free shopping. In addition, it was confirmed that subjective norms, which are opinions of the reference group, are an important factor in inducing desire [78,79].

Among the factors of technology beliefs, factors affecting attitude were found to be compatibility and perceived usefulness. As a result of existing internet shopping-related research, it was found that perceived usefulness had a relatively greater influence on attitude than perceived enjoyment [17,80,81].

Compared to existing offline duty-free shops, online duty-free shops have many advantages in terms of price and time. Duty-free shop users are responding favorably to online duty-free shops, since they are obtaining practical benefits. To use online duty-free shops, technology utilization skills must be premised, unlike offline skills. Hence, one’s will and beliefs are the only limits to using online shops. While existing studies have shown that the easier it is to use technology, the greater the perceived enjoyment and the more it affects attitude, this study showed different results. It indicated that if a user felt that to use an online duty-free shop was easy, it was fun, but attitude was put on hold. In this regard, practically, it is necessary to consider an appropriate difficulty level in developing an online duty-free shop channel.

6. Implications

This research model was constructed on the basis of representative theories of the technology acceptance model to examine the process of technology innovation acceptance in online duty-free shops. Both theoretical and practical contributions were made, increasing the ability to explain the phenomenon of online duty-free shops through theoretical mutual complementation. First, it is judged that the decomposed theory of planned behavior model proposed in this study is a result that can be applied to new purchasing channels like online duty-free shops by reaffirming the validity of the existing TAM and TPB models. In this study, the behavioral intentions of online duty-free shops were examined using the detailed planned behavior model proposed by Taylor and Todd [8,9], and the same results as in previous studies were found [67,68,82,83,84,85].

Second, as with the study results presented by Culos-Reed, Gyurcsik and Brawley [86], and Rivis and Sheeran [87], in the subjective norms explaining behavioral intention, the contribution was relatively lower than attitude. It was confirmed that one’s own intention was more important than the intentions of surrounding people in effecting certain behaviors. The factors affecting the subjective norms were found to be the internal and external influence. Therefore, to approach a customer’s neighbors, a strategy is needed to actively promote the use of duty-free shops through SNS and the media. Kelly et al. [88] found that corporate marketing activities using social media and media help companies build personal relationships with consumers and provide opportunities to get closer to customers through social communities. Online duty-free marketers are expected to approach consumers through social media marketing strategies and have a significant influence on purchasing decisions.

Third, as revealed by the study results of Lu et al. [22], perceived ease of use affected perceived usefulness, which in turn affected the attitude of the duty-free shop users. To promote the use of online duty-free shops, the use process must be convenient and easy, as it is with online banking, which is popular and free from consumer resistance. Currently, the usage rate of mobile banking applications has exceeded the usage rate of direct visits to banks (branch offices) [89]. Fourth, offline duty-free shops have the advantage of providing immediate satisfaction by directly viewing and touching products, and online duty-free shops have the advantage of relatively low prices and a wide variety of products compared to offline duty-free shops [90]. As the trend of low growth continues, the demand for simple and fast services is increasing, due to the seeking of low-price products and proliferation of smartphones. In other words, consumers’ consumption is shifting to a downward purchase pattern, and most users using online duty-free shops tend to identify in advance the products they want to purchase by visiting department stores or downtown duty-free shops. Therefore, duty-free shops should also try to strengthen their competitiveness by devising a low-price package strategy. Fifth, to survive in the competitive structure with overseas duty-free shops and overseas shopping malls rather than bleeding competition among domestic duty-free shops, it is necessary to take preemptive measures. Cooperation between airport duty-free shops and downtown duty-free shops is also required. On-offline boundaries have been breaking down in recent years, so it is necessary to apply an omni-channel method. Through the adoption of online and offline complex services, it is necessary to achieve qualitative growth that improves profitability along with the external growth of online channels.

The limitations of this research are as follows. First, there is a problem arising from the questionnaire. The sample group responding to the questionnaire was biased toward respondents in their 20s and 30s, which did not sufficiently reflect the situation of other groups. Therefore, in future studies, research should be conducted on online duty-free shop users of various age groups. Moreover, since online duty-free shop users vary in nationality, in-depth studies that analyze differences between groups will be needed. Second, in addition to the factors suggested in this research, there is a necessity to apply major variables such as price sensitivity, that can reflect the characteristics of duty-free shops. This study is also limited in that it did consider the shopping amount and demographic variables. Because differentiating factors can play a role in online duty-free shops, behavioral intentions according to shopping amounts and demographic variables should be conducted by using moderating effects and control variables. It is hoped that future studies will produce continuous and concrete research results that are not covered in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-J.C. and J.-W.P.; methodology, Y.-J.C. and J.-W.P.; data collection and analysis, and Y.-J.C. supervision of the research, J.-W.P.; writing original draft, Y.-J.C.; writing—review & editing Y.-J.C. and J.-W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Omar, O.; Kent, A. International Airport Influences on Impulsive Shopping: Trait and Normative Approach. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2001, 29, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Lee, K.H. How Can Marketers Overcome Consumer Resistance to Innovations? -the Investigation of Psychological and Social Origins of Consumer Resistance to Innovations. J. Glob. Acad. Market. Sci. 2005, 15, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecasteele, B.; Geuens, M. Motivated Consumer Innovativeness: Concept, Measurement, and Validation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2010, 27, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, S.; Harris, M.A. Gender and e-Commerce: An Exploratory Study. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.; Walsh, G. Gender Differences in German Consumer decision-making Styles. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2004, 3, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, S.; Lohse, G.L.; Johnson, E.J. Predictors of Online Buying Behavior. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzan, M. Consumers Online and Offline Shopping Behavior; Report no.-2014.15.14., Student no. 5124890; Swedish School of Textiles: Borås, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- South Korea Customs Service, Korea Duty Free Shops Association. 2019. Available online: https://www.trndf.com/newsView/trn201804020004 (accessed on 24 March 2018).

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Jang, S.Y.; Kim, A.K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Genetically Modified Foods: Moderating Effects of Food Technology Neophobia. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and Crossover Effects in the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Study of Consumer Adoption Intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Attitudes, Intentions, and Behavior: A Test of some Key Hypotheses. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A.; Kavas, A. The Theory of Reasoned Action Applied to Coupon Usage. J. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Jensen, J.M.; Solgaard, H. Predicting Online Grocery Buying Intention: A Comparison of the Theory of Reasoned Action and the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Inform. Mngt. 2004, 246, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Kim, Y. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web Context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Klein, K.J. Innovation Characteristics and Innovation Adoption-Implementation: A Meta-Analysis of Findings. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1982, 1, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Model of the Antecedents of Perceived Ease of use: Development and Test. Decis. Sci. 1996, 27, 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V. Determinants of Perceived Ease of use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2000, 11, 342–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, B. Exploring Chinese Users’ Acceptance of Instant Messaging using the Theory of Planned Behavior, the Technology Acceptance Model, and the Flow Theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T.L.; Carr, C.L.; Peck, J.; Carson, S. Hedonic and Utilitarian Motivations for Online Retail Shopping Behavior. J. Retail. 2002, 77, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heijden, H. User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Q. 2004, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Yung, Y. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.; Lu, H. Towards an Understanding of the Behavioural Intention to use a Web Site. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2000, 20, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Empathy and its Origins in Early Development. In Intersubjective Communication and Emotion in Early Ontogeny; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. The Diffusion of Innovations, 3rd ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, K. Predicting User Intentions: Comparing the Technology Acceptance Model with the Theory of Planned Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, E. Consumer Adoption of the Internet for Apparel Shopping. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Somali, S.A.; Gholami, R.; Clegg, B. An Investigation into the Acceptance of Online Banking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation 2009, 29, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, A. Computers and Other Interactive Technologies for the Home. Commun. ACM 1996, 39, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.B.; Zmud, R.W. Information Technology Implementation Research: A Technological Diffusion Approach. Manag. Sci. 1990, 36, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwick, J.; Barki, H. Explaining the Role of User Participation in Information System use. Manag. Sci. 1994, 40, 440–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnkrant, R.E.; Page, T.J. The Structure and Antecedents of the Normative and Attitudinal Components of Fishbein’s Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 24, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Khalifa, M.; Frini, A. What Makes Consumers Buy from Internet? A Longitudinal Study of Online Shopping. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 2000, 30, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The Prediction of Behavior from Attitudinal and Normative Variables. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 6, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: Tampa, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy Mechanism in Human Agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, M.; Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Post-Adoption Behavior in the Context of Online Services. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C.A. Assessment of Computer Self-Efficacy: Instrument Development and Validation. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the National Council Measurement in Education, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2 April 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Schunk, D.H. Cultivating Competence, Self-Efficacy, and Intrinsic Interest through Proximal Self-Motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 41, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Higgins, C.A.; Howell, J.M. Personal Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of Utilization. MIS Q. 1991, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.K.; Cheung, W. Determinants of the Intention to use Internet/WWW at Work: A Confirmatory Study. Inf. Manag. 2001, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M. Flexibility in Access, Interaction and Assessment: The Case for Web-Based Teaching Programs. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 1997, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Rivard, S.; De Serre, L. Investigating the Support Role of the Information Center. MIS Q. 1990, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The Explanatory and Predictive Scope of Self-Efficacy Theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Lee, K. Consumer Resistance to, and Acceptance of, Innovations. Adv. Consum. Res. 1999, 26, 218–225. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, H.; Dubinsky, A.J. Consumers’ Perceptions of e-shopping Characteristics: An expectancy-value Approach. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. Shopping Online for Freedom, Control, and Fun. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’cass, A.; Fenech, T. Web Retailing Adoption: Exploring the Nature of Internet Users Web Retailing Behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and Purchase Consequences of Customer Participation in Small Group Brand Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.; Huang, H. Understanding Customers’ Repeat Purchase Intentions in B2C e-commerce: The Roles of Utilitarian Value, Hedonic Value and Perceived Risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, Habits and Rational Choices in Ecological Behaviours: The Case of Recycling and use of Public Transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A. The Addition of Anticipated Regret to Attitudinally Based, goal-directed Models of Information Search Behaviours under Conditions of Uncertainty and Risk. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 46, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, W.A. The Two Senses of Desire. Philos. Stud. 1984, 45, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-Directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P. Physicians’ Acceptance of Electronic Medical Records Exchange: An Extension of the Decomposed TPB Model with Institutional Trust and Perceived Risk. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2015, 84, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J. Investigation of the Volitional, Non-Volitional, Emotional, Motivational and Automatic Processes in Determining Golfers’ Intention. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 1118–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Han, H. Effect of Environmental Perceptions on Bicycle Travelers’ Decision-Making Process: Developing an Extended Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Lee, C.; Reisinger, Y.; Xu, H. The Role of Visa Exemption in Chinese Tourists’ Decision-Making: A Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.; Ku, Y.; Chien, J. Understanding Physicians’ Acceptance of the Medline System for Practicing Evidence-Based Medicine: A Decomposed TPB Model. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2012, 81, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K. Consumer Technology Traits in Determining Mobile Shopping Adoption: An Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.; Chiu, C. Internet Self-Efficacy and Electronic Service Acceptance. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 38, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjan, H.; Hartshorne, R. Investigating Faculty Decisions to Adopt Web 2.0 Technologies: Theory and Empirical Tests. Internet High. Educ. 2008, 11, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KhaliL, M.N. An Empirical Study of Internet Banking Acceptance in Malaysia: An Extended Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Management, College of Business and Administration, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, CO, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Tsou, C.; Shu, Y. The Roles of Perceived Enjoyment and Price Perception in Determining Acceptance of Multimedia-on-Demand. Int. J. Bus. Inf. 2008, 3, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nejati, M.; Moghaddam, P.P. Gender Differences in Hedonic Values, Utilitarian Values and Behavioural Intentions of Young Consumers: Insights from Iran. Young Consum. 2012, 13, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lekhawipat, W. Factors Affecting Online Repurchase Intention. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, P. Why We Buy: The Science of Shopping—Updated and Revised for the Internet, the Global Consumer, and Beyond; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 13 9781416595243. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.; Kang, S.K.; Boo, S. The Effect of Environmentally Friendly Perceptions on Festival Visitors’ Decision-Making Process using an Extended Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.P. An empirical study on predicting user acceptance of e-shopping on the Web. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, M.; Drennan, J.; Previte, J.; White, A.; Tjondronegoro, D. The Role of Desire in Understanding Intentions to Drink Responsibly: An Application of the Model of Goal-Directed Behaviour. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 30, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.S.; Yoon, S.J. Predicting Purchase Intent on Social Commerce: Use of TPB (Theory of Planned Behavior), and TRI (Technology Readiness). J. Korea Serv. Manag. Soc. 2013, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Edwards, E.A. Goal-Striving and the Implementation of Goal Intentions in the Regulation of Body Weight. Psychol. Health 2000, 15, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.; Candel, M.J. The Consumption of Convenience Foods: Reference Groups and Eating Situations. Food Qual. Prefer. 1999, 10, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.; Lim, V.K.; Lai, R.Y. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in Internet Usage. Omega 1999, 27, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramayah, T.; Rouibah, K.; Gopi, M.; Rangel, G.J. A Decomposed Theory of Reasoned Action to Explain Intention to use Internet Stock Trading among Malaysian Investors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeder, M.J.; Mohammed, U.; Sugai, P. Study of Consumer Attitudes towards Connected Reader Devices in Japan Based on the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior. Econ. Manag. Ser. 2011, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, Y.; Fang, K. The use of a Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior to Study Internet Banking in Taiwan. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Wang, Y.; Wen, S. Using the Decomposed Theory of Planning Behavioural to Analyse Consumer Behavioural Intention Towards Mobile Text Message Coupons. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2006, 14, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culos-Reed, S.; Gyurcsik, N.; Brawley, L. Using Theories of Motivated Behavior to Understand Physical Activity. Handb. Sport Psychol. 2001, 2, 695–717. [Google Scholar]

- Rivis, A.; Sheeran, P. Descriptive Norms as an Additional Predictor in the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2003, 22, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Kerr, G.; Drennan, J. Avoidance of Advertising in Social Networking Sites: The Teenage Perspective. J. Interact. Advert. 2010, 10, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrain Trend Monitor. 2017. Available online: https://www.trendmonitor.co.kr/tmweb/trend/allTrend/detail.do?bIdx=1851&code=0601&trendType=CKOREA (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Cavallo, A. Are Online and Offline Prices Similar? Evidence from Large Multi-Channel retailers. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 283–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).