An Overarching Model for Cross-Sector Strategic Transitions towards Sustainability in Municipalities and Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

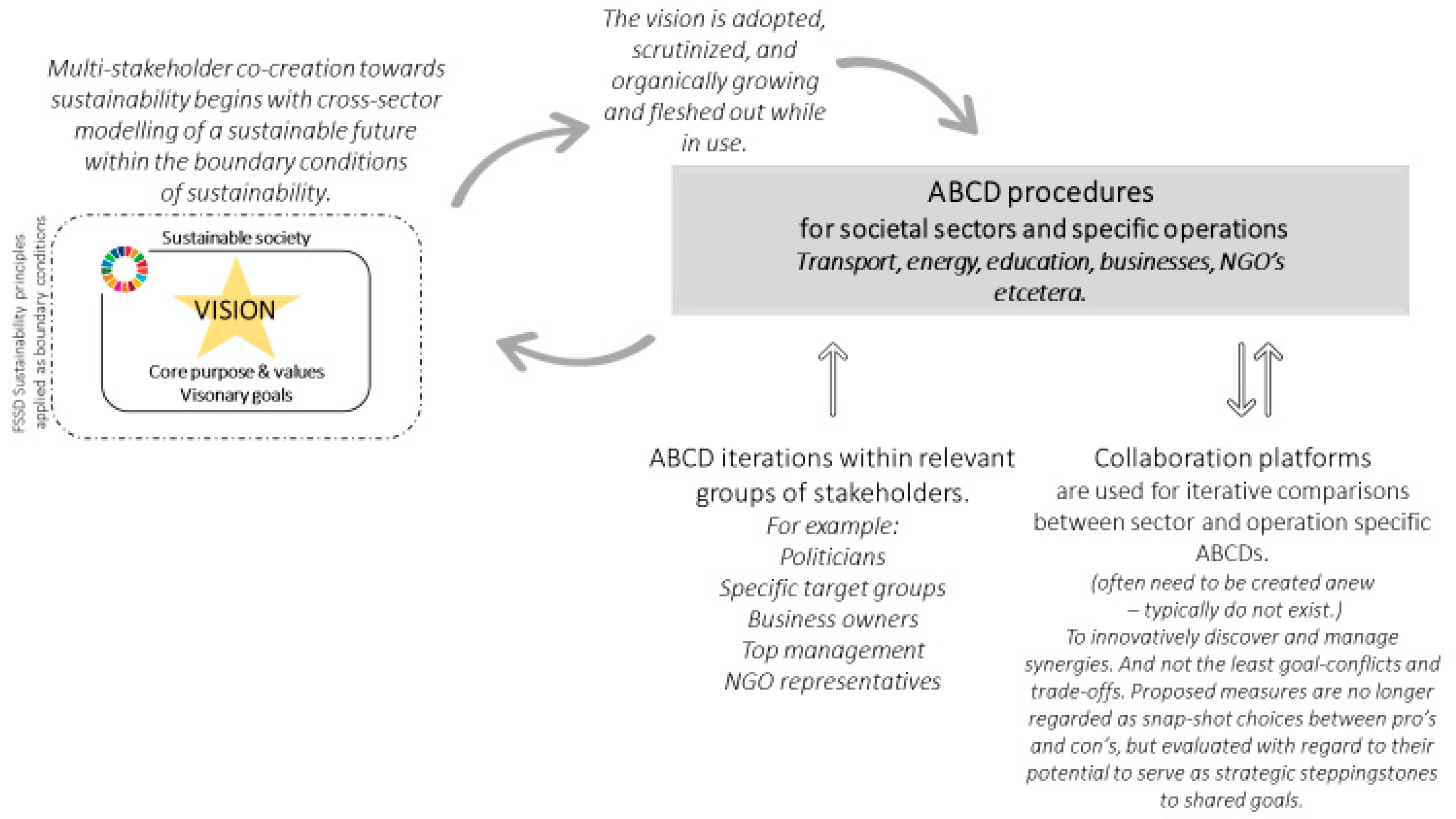

2. Model for Long-Term Implementation of the Framework for Strategic Sustainable Development

3. Method

3.1. Participatory Action Research

- Decision to participate in the PAR project and set up. Establishment of a core team and internal communication channels with decision-makers. Good contact channels for interactions between the municipal partners on the one hand, and the university on the other.

- Introduction of the FSSD, the preliminary long-term implementation model and the PAR project to decision-makers and people in strategic positions. Explaining the FSSD and its rationale of applying first-order sustainability principles as boundary conditions for cross-sector modelling of goals (A), sustainability analyses (B), brainstorming of options (C) and prioritized actions into the redesign (D).

- Assessment of the municipality’s or region’s current strategic sustainability work seen through the lens of the FSSD implementation model.

- Development, and/or scrutinizing existing municipal/regional vision from a sustainability perspective given by the FSSD boundary conditions.

- ABCD procedures for the overall geographic municipality or region.

- In parallel, ABCD procedures for more detailed focus areas, for example, individual sectors such as energy, transport, or the food system, but also smaller focus areas such as a specific municipal operations, processes, projects or efforts to design more strategic routines, for example, for procurement.

- Comparisons of ABCD results through varying collaboration platforms between sectors and operations within, as well as between municipalities and regions. Shared reflections and co-learning between all participants in the study.

- ABCD iterations, i.e., learning harvested from results, evaluation and comparisons of ABCD processes are fed into repeated ABCDs in an ongoing development process for a specific focus area, sector or the overarching municipality/region.

3.1.1. Data Collection

- Documentation of Observations, Dialogues, and Reflections

- Survey on the Presentation and Round Table Workshop at SEKOM Conference April 2016

3.1.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Actions and Results from Processes within the PAR Project Phase 1, 2015–2018

4.2. Learnings from Applying the Preliminary Implementation Model

4.2.1. Reported Strengths of the FSSD Implementation Model

4.2.2. Reported Weaknesses of the FSSD Implementation Model

4.2.3. Reported Barriers of the FSSD Implementation Model

4.2.4. Reported Enablers of the FSSD Implementation Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Guidance for how to better introduce the FSSD and its implementation model amongst leaders and decision makers—their active part in the co-creation of plans, monitoring of progress and communications is key. For example, presenting the concrete “business case” (economical self-benefit) for sustainability [11,12]. Furthermore, showcasing how the strategic methodology is designed to (i) support strategic leadership of any kind as well as (ii) providing know-how regarding the integration of sustainability with all other goals and finding synergies between them, and (iii) create comprehension and cohesion of concepts and tools for decision support, monitoring and communications.

- Instructions for initial capacity-building ABCD procedures and workshops to be run with top management, assuring that enough resources will be allocated over time, such as sufficient competence, prerequisites for cross-sector collaboration and decision-making capacity, and, additionally, to anchor the need of infrastructures and norms for active cross-sector cooperation of any kind, preferably by developing more effective relationships between already active platforms.

- Inspiration of how to put together a core team helping to release individual burdens and balance potential staff turnover—making what they need to do anyhow easier.

- Upfront training of moderators. This includes an ABCD manual for practitioners, both for running independent ABCD processes and as education material for train-the-trainer procedures.

- Instructions/inspiration for how to keep up processes and momentum, for example, how to transfer results from one ABCD workshop (measures under previous D-list) to the next (new ABCD workshop’s B list) and good examples and best practices of supportive structures and tools (such as innovative collaboration platforms, communication strategies, and hands-on advice for how to apply the ABCD mindset to use various support-tools and concepts effectively in cohesion).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krause, R.M.; Feiock, R.C.; Hawkins, C.V. The Administrative Organization of Sustainability Within Local Government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W. (Ed.) Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In A New Era in Global Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-8261-9011-6. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, B.L.; Borén, T. Barriers to implementing sustainability locally: A case study of policy immobilities. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 1489–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bueren, E.; De Jong, J. Establishing sustainability: Policy successes and failures. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, S. In pursuit of resilient, low carbon communities: An examination of barriers to action in three Canadian cities. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7575–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, J.A.; Moser, S.C. Identifying and overcoming barriers in urban climate adaptation: Case study findings from the San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA. Urban Clim. 2014, 9, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Hanna, K.; Dale, A. A template for integrated community sustainability planning. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wälitalo, L.; Callaghan, E.; Robért, K.-H.; Broman, G. Identifying barriers to effective transitioning towards sustainability in municipalities and regions. 2020; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, C.; Stamer, A.; Heckathorn, A. A Guide for the Strategic Analysis of Frameworks for Municipal Sustainability Planning. Master’s Thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Broman, G.I.; Robèrt, K.-H. A framework for strategic sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140 Pt 1, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, J.; Robert, K.-H. Backcasting—A framework for strategic planning. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2000, 7, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. Prisoners’ dilemma misleads business and policy making. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. A strategic approach to social sustainability—Part 1: Exploring the social system. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140 Pt 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robèrt, K.-H.; Borén, S.; Ny, H.; Broman, G. A strategic approach to sustainable transport system development—Part 1: Attempting a generic community planning process model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robèrt, K.-H.; Schmidt-Bleek, B.; Aloisi de Larderel, J.; Basile, G.; Jansen, J.L.; Kuehr, R.; Price Thomas, P.; Suzuki, M.; Hawken, P.; Wackernagel, M. Strategic sustainable development—Selection, design and synergies of applied tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEKOM. Sveriges Ekokommuner—Världens Äldsta Kommunnätverk för Hållbar Utveckling. Available online: http://www.sekom.se/ (accessed on 1 January 2018).

- Blekinge Institute of Technology (BTH). Stöd för Ökad Hållbarhet. Available online: https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/bth/pressreleases/stoed-foer-oekad-haallbarhet-1135433 (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Sveriges Ekokommuner. Available online: http://www.sekom.se/In-English (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- SKR. Kommunalt Självstyre. Available online: https://skr.se/demokratiledningstyrning/politiskstyrningfortroendevalda/kommunaltsjalvstyresastyrskommunenochregionen.380.html (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- SKR. Regionernas Åtaganden. Available online: https://skr.se/tjanster/kommunerochregioner/faktakommunerochregioner/regionernasataganden.27748.html (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- McIntyre, A. Participatory Action Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bärkraft.ax. Available online: https://www.barkraft.ax/english (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Bryant, J.; Thomson, G. Learning as a key leverage point for sustainability transformations: A case study of a local government in Perth, Western Australia. Sustain. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cittaslow International. Available online: http://www.cittaslow.org/ (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- LEED for Cities and Communities. Available online: https://new.usgbc.org/leed-for-cities (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- OnePlanet. Available online: https://www.oneplanet-ngo.org/ (accessed on 3 June 2019).

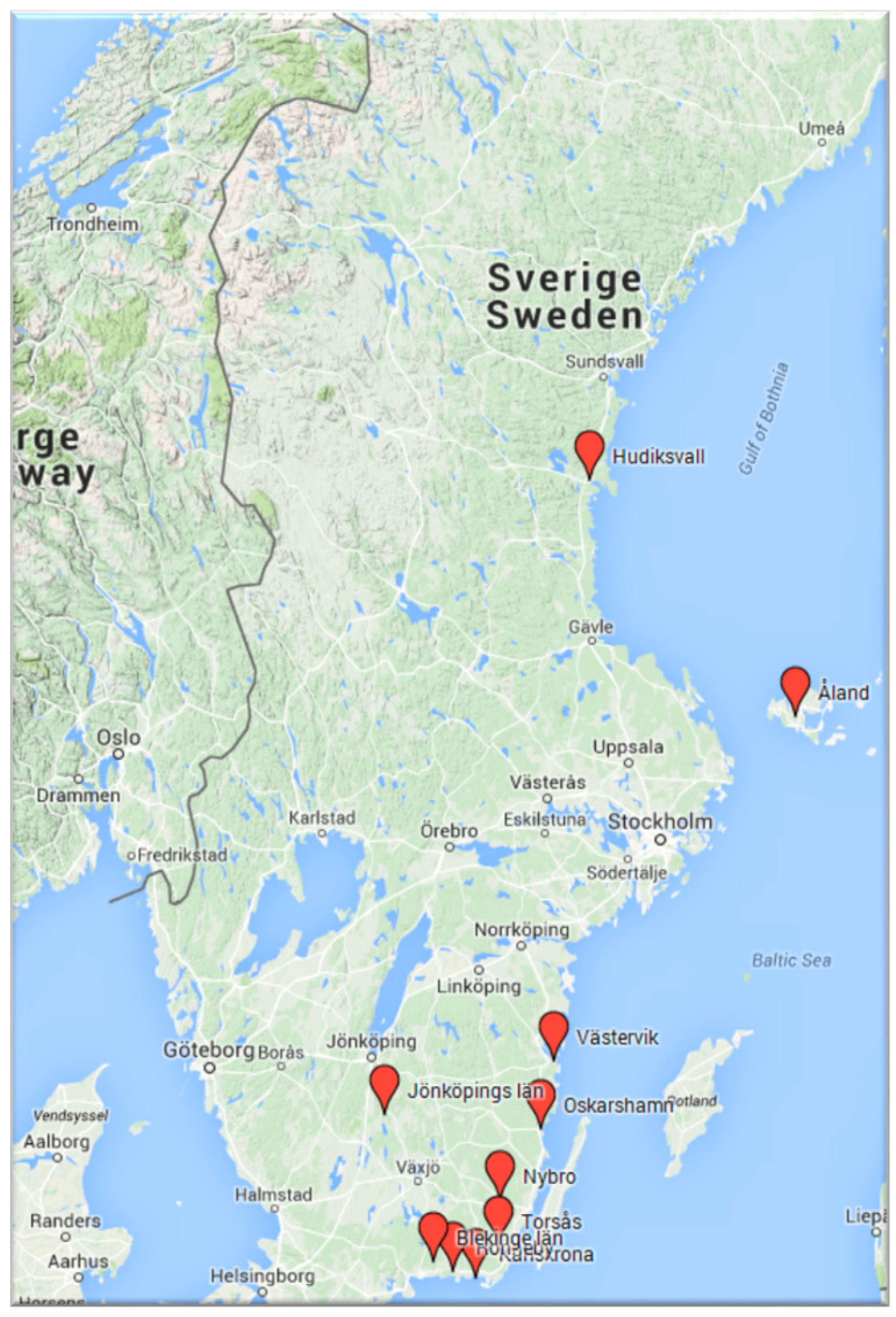

| Partner | Decision to Participate in the Par Project, Establishment of Core Team and Communication Channels | General Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Participation initiated by civil servants and politicians. Good political buy in and support sticks out in this municipality. One key contact. Core team of 2 to 3 civil servants. Good relationship with administrative head and leading politicians through steering group for ecological sustainability. | Knowledge and understanding of the intendent process should be well established with decision-makers. More action related to the PAR project could be seen when initiative to participate came from both civil servants and politicians. Initial support for anchoring the purpose and need of the FSSD implementation model is requested from key contacts as a prerequisite for them to independently be able to continue the work (presentation material, videos, good examples and best practices etc.) Part time politicians in small municipalities and multitasking civil servants lack time for strategic sustainability work. A well working core team and good political anchoring are key to deal with for example (sudden) personnel turnover, re-organizations and elections. Practitioners pointed out that having a network appointed upfront is crucial for evolving traditions and norms for sharing results and good practices. |

| Karlskrona | Initiated by civil servants. Moderate political support. Contact persons and core teams were assigned dependent on ABCD focus. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Nybro | Initiated by civil servants. Moderate political support. One key contact. Core team of 2–3 civil servants. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Oskarshamn | Initiated by civil servants. Moderate political support. One key contact. No clear core team. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Region Blekinge | Initiated by civil servants. Moderate political support. One key contact. No clear core team. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Region Jönköpings Län | Initiated by civil servants. Moderate political support. Initial key contact left his position within one year of the project. Consultant took over. No core team. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Ronneby | Initiated by civil servants. Low political support. Initial key contact left her position halfway into the project. No clear core team. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Torsås | Initiated by civil servants and politicians. Moderate political support. One key contact on half time and occasionally on sick leave. No core team. Politicians briefed informally and through occasional presentations to the municipal board, but no clear commitment nor decisions on communication channels for the PAR project. | |

| Västervik | Initiated by civil servants and politicians. Moderate political support. One key contact. No core team. Some political commitment but poor internal communication between politicians and administration. | |

| Åland | Initiated by civil servants and politicians. High political support. One key contact changed after one year. Core team established through ambitious regional initiative. Politics involved and briefed on a regular basis through the specifically established network of a viable Åland (www.barkraft.ax). |

| Partner | Introduction of the FSSD, the Implementation Model and the Par Project to Decision-Makers and People in Strategic Positions | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | September 2015-about 40 people. Politicians from sustainability and welfare committees + some civil servants participated. Continued and broadened introductions outside the core team, including offered training/education. | Introduction and learning regarding the processes introduced through FSSD and the implementation model must happen continuously. A majority of partners did not plan for a continuous introduction and was not sufficiently instructed to do so. At the same time, not everyone in a municipality/region is in need of knowing all details about specific concepts and methods for strategic sustainable development (SSD). Participants emphasized the need for a communication plan regarding SSD and to clarify sufficient levels of information for specific target groups (e.g., leading politicians, managers and people in operational roles). Further, for successful anchoring of the FSSD implementation model, practitioners highlighted a need to clarify alignment between what the model proposes in context of existing governance and management systems. |

| Karlskrona | September 2015-about 20 politicians in the municipal board and a few civil servants. Continuous introductions of the implementation model within specific focus areas (see ABCD processes for focus areas below). | |

| Nybro | November 2015-about 40 people. Politicians from the municipal board + other councils and civil servants | |

| Oskarshamn | August 2015–35 people. About 20 civil servants and 15 politicians. | |

| Region Blekinge | October 2015 About 20 politicians in the regional board. Further introductions in relation to focus area ABCDs (see ABCD processes for focus areas below). | |

| Region Jönköpings Län | August 2015-About 25 people, whereof 10 civil servants and 15 politicians in the regional board. Further introductions in relation to focus area ABCDs (see ABCD processes for focus areas below). | |

| Ronneby | January and April 2016 January: heads of departments-10 people. April: Politicians in the municipal board and heads of departments-30 people. | |

| Torsås | May 2015-Politicians in the municipal board and heads of departments-30 people. Further introductions in relation to focus area ABCDs (see ABCD processes for focus areas below). | |

| Västervik | April 2015-About 15 people. Mainly civil servants in Västervik Sustainability network. | |

| Åland | June 2015 About 20 people, mix of civil servants, responsible politicians and engaged sector representatives. Continuous broad introduction and introduction through focus areas (see ABCD processes for focus areas below). |

| Partner | Assessment of the Municipality’s/Region’s Current Strategic Sustainability Work through the Lens of the FSSD Implementation Model | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Analysis of the current situation, viewed through a lens of the implementation model, aimed to highlight and take advantage of everything that was already done in relation to the various steps in the process and at the same time to see if it was possible to discover any gaps for strategic sustainability work in the municipality/region. Interviews, observations and reviews of partners’ websites, as well as document analysis of strategies/plans/policies were carried out. | These assessments are work in progress and will continue over phase two of the PAR project. Many dialogues have been carried out based on preliminary results, however, these are not yet summarized. |

| Karlskrona | ||

| Nybro | ||

| Oskarshamn | ||

| Region Blekinge | ||

| Region Jönköpings Län | ||

| Ronneby | ||

| Torsås | ||

| Västervik | ||

| Åland |

| Partner | Expert Moderated Developments/Quality Checks of Municipal/Regional Visions from A Sustainability Perspective (A) | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Workshop Sept 2015: quality check of existing vision. Led to supplementation of text in the specification of the overall goals. | Conceptual confusions regarding visions were relatively common among practitioners. What is a vision? Is it synonymous to an attractive goal co-created across sectors? Less or more specific than that? And what has sustainability got to do with it? Support and examples are asked for. The FSSD visioning process is perhaps the first-time practitioners realise the need to integrate sustainability into what kind of desired overall future they want for their municipality/region, which can reveal conflict of interests and initial resistance. |

| Karlskrona | Workshop Sept 2015: quality check of existing vision. No specific improvements. | |

| Nybro | November 2015: Visioning workshop carried out. Results applied in continuing visioning processes outside of research project. | |

| Oskarshamn | August 2015: quality check of existing vision. Result implemented in new Sustainability programme. | |

| Region Blekinge | No workshop done. Vision already in place that refer to the FSSD sustainability principles. | |

| Region Jönköpings Län | No workshop done. Vision already in place and not considered necessary to update at that time. | |

| Ronneby | December 2016: Process input to visioning workshop. Resulted in new overarching vision presented in budget 2017. | |

| Torsås | Spring 2017: Input to Torsås’ vision through ABCD processes with eight graders. | |

| Västervik | Planned October 2015 but cancelled. Postponed to spring 2016 but not realised. | |

| Åland | March 2016: Visioning workshop with approx. 100 participants from all societal sectors. Vision developed in spring 2016 and elaborated in a development and sustainability agenda for Åland including a vision statement and seven overarching development goals (see https://www.barkraft.ax/). |

| Partner | ABCD Procedures for Planning in the Overall Geographic Municipality or Region | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Initiated an overall baseline/sustainability analysis (B), including a process for scrutinising social sustainability through social boundary conditions. To be continued. Additional support was asked for. Identified a need for capacity-building within the organisation and launched broad educational support to staff (mainly on C/D steps of the ABCD) | The visioning process took a lot of energy and, due to generally weak mandates for the whole process in partner municipalities and regions, not enough initiative could be gathered for full B, C and D steps at an overarching level. Instead, this happened in a more ad hoc, unprepared way. This step is closely related to the step Assessment of the municipality’s/region’s current strategic sustainability work through the lens of the FSSD implementation model (see above). Baseline analyses were initiated in partner municipalities that had key contacts well informed about the PAR project, FSSD and preferably had a well working core team. Insufficient defining of the gap between baseline (B) and a vision of success (A) risks resulting in insufficient actions from a full sustainability perspective. Clear instructions for how to perform a FSSD Baseline analysis for a whole municipality/region were missing. Such instructions were identified as needed support and can be developed from initial experiences. It was noted as important to make use of existing data, solutions and ideas for baseline analysis (B) as well as idea generation (C/D). |

| Karlskrona | Baseline/sustainability analysis (B) discussed but not initiated. | |

| Nybro | Initiated a baseline/sustainability analysis (B). Additional support was asked for. Initiated work towards a Sustainability programme for the whole municipality (mainly on C/D steps of the ABCD). | |

| Oskarshamn | Initiated baseline/sustainability analysis (B). Additional support was asked for. | |

| Region Blekinge | No. However discussed ABCD procedure of forthcoming revision of the Regional development strategy. | |

| Region Jönköpings Län | No action during PAR project. | |

| Ronneby | No action during PAR project. | |

| Torsås | No action during PAR project. | |

| Västervik | No action during PAR project. | |

| Åland | The PAR project gave process input to overall baseline analyses (B). Internal experts with FSSD competence ran process. Annual progress reports were produced (three so far 2017–2019). Development and sustainability agenda produced to guide continuous work (mainly around C/D of the ABCD). Network established (www.barkraft.ax) to be the hub for the coordination of developments aligned with the sustainability agenda. Road maps for different organizations and sectors are developed, as well as road maps for the seven development goals which will be launched digitally during year 2020. The ABCD process is communicated and partially applied as a common planning procedure. |

| Partner | ABCD Processes for Focus Areas | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Initiated: Planned application of ABCD for developments of the new comprehensive plan. One initial half-day workshop with politicians and civil servants. No results during phase one of the research project. | Besides visioning workshops, most actions during the PAR project occurred within focus area ABCDs. Focus area ABCDs are more hands on than overall planning and show concrete results faster. Although, long term application of the ABCD procedure within municipalities and regions is ideally an interplay between the overall perspective, societal sectors and focus areas. Specific results should be related to a common vision of success and other specific ABCD procedures for comparison and search of synergies/conflicts. Specific ABCD procedures (focuses) can create more and more ripples on the water, leading to extended knowledge and increased interest about the approach. A potential “back door” to establishing political good will and mandate. |

| Karlskrona | Completed first ABCD round: Social sustainability for children and youth. Strategy and action plan developed and completed. Many different stakeholder groups participated during several meetings and workshops; youth, teachers, the police, NGOs etcetera. Completed first ABCD round: The municipal procurement process. Goals, baseline and solutions were identified through workshops resulting in an action plan for sustainable procurement. A core team around head of procurement met several times and civil servants from all municipal departments participated in a half-day workshop. Initiated: Department for operations and services. Introduction at department meeting and one 3 h workshop with management group completed. | |

| Nybro | No action during PAR project. | |

| Oskarshamn | A group of spatial planners tested the ABCD process at the focus “infrastructure” as a sub-part of the comprehensive plan. | |

| Region Blekinge | Completed first ABCD round: Procedures for Regional growth funding. Led to developed instructions for applicants and a foundation for an online web tool that position applications in relation to sustainability. People from the Project office participate in two half-day workshops and continuous work. | |

| Region Jönköpings Län | Initiated ABCD process for the regional administration and its operations. Input to a sustainability programme for internal operations. https://www.rjl.se/om-oss/Budget-och-utvecklingsplaner/program-for-hallbar-utveckling/. Representatives from different operations participated in a full-day workshop. | |

| Ronneby | No action during PAR project. | |

| Torsås | Initiated ABCD process for development of strategy towards Fossil-fuel free municipality 2030. The municipal administration’s manager group participated in a full-day workshop. | |

| Västervik | Process input to work with water quality. | |

| Åland | Completed first ABCD round within research project: Sustainable food system. Input to Strategy for a sustainable food system at Åland (https://landsbygd.ax/livsmedelsstrategin/). Executed through a Delphi procedure (three web-based survey rounds) with 80 participants from all societal sectors and ended with a half-day workshop. Process input to: Sustainable drinking water supply (https://vattenskydd.ax/en/sustainable-drinking-water/). Additional processes can be found at https://www.barkraft.ax/english. |

| Partner | Comparisons of ABCD Results through Collaboration Platforms within, as Well as between Municipalities and Regions | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | Most of the partner municipalities and regions did not reach this step and we realised it was unrealistic within the limited project period. Nevertheless, Karlskrona and Åland were able to run two separate ABCD focus procedures which led to informal comparisons through people that had participated in both processes. Additionally, Åland launched a broad collaboration platform, www.barkraft.ax. The network is the hub for the coordination of the work to realize the development and sustainability agenda and was formed at the initiative of the stakeholders from the public sector, businesses, associations, and education sector. Comparisons between partner municipalities and regions happened during annual project meetings and webinars, 11 in total. Comparisons focused on procedures rather than concrete results. Indirect comparisons/learnings happened through intermediation of results between researchers and the partners during meetings. Project participants also shared results and experiences through a common and web-based workspace. | Practitioners found it helpful to learn from each other and emphasized a desire and need to continue doing that. For example, through study visits, attending workshops as observers and by exchanging of guest lectures. Identified additional support: A tool (digital) for communication of results, comparisons for inspiration and learning and celebration of victories. Practitioners also reflected of the importance to make use of, be inspired by and/or invite existing collaboration initiatives to co-creation. |

| Karlskrona | ||

| Nybro | ||

| Oskarshamn | ||

| Region Blekinge | ||

| Region Jönköpings Län | ||

| Ronneby | ||

| Torsås | ||

| Västervik | ||

| Åland |

| Partner | ABCD Iterations Based on Results of Processes, Comparisons and Evaluation | Overarching Reflections from Observations and Dialogues with Project Partners |

|---|---|---|

| Hudiksvall | No iterations of specific or overall ABCD processes happen for any of the participating partners during the limited PAR project period. | The FSSD implementation model implies a long-term progress and ABCD iterations turned out not to be realistic during the project period. |

| Karlskrona | ||

| Nybro | ||

| Oskarshamn | ||

| Region Blekinge | ||

| Region Jönköpings Län | ||

| Ronneby | ||

| Torsås | ||

| Västervik | ||

| Åland |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wälitalo, L.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. An Overarching Model for Cross-Sector Strategic Transitions towards Sustainability in Municipalities and Regions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177046

Wälitalo L, Robèrt K-H, Broman G. An Overarching Model for Cross-Sector Strategic Transitions towards Sustainability in Municipalities and Regions. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177046

Chicago/Turabian StyleWälitalo, Lisa, Karl-Henrik Robèrt, and Göran Broman. 2020. "An Overarching Model for Cross-Sector Strategic Transitions towards Sustainability in Municipalities and Regions" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177046

APA StyleWälitalo, L., Robèrt, K.-H., & Broman, G. (2020). An Overarching Model for Cross-Sector Strategic Transitions towards Sustainability in Municipalities and Regions. Sustainability, 12(17), 7046. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177046