Effective Communication Strategies of Sustainable Hospitality: A Qualitative Exploration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability Issues in Hospitality

2.2. Customer Relationship Management in Hospitality

2.3. Communication in Sustainability

2.4. Communicating Sustainability in Hospitality

3. Methodology

4. Findings and Discussions

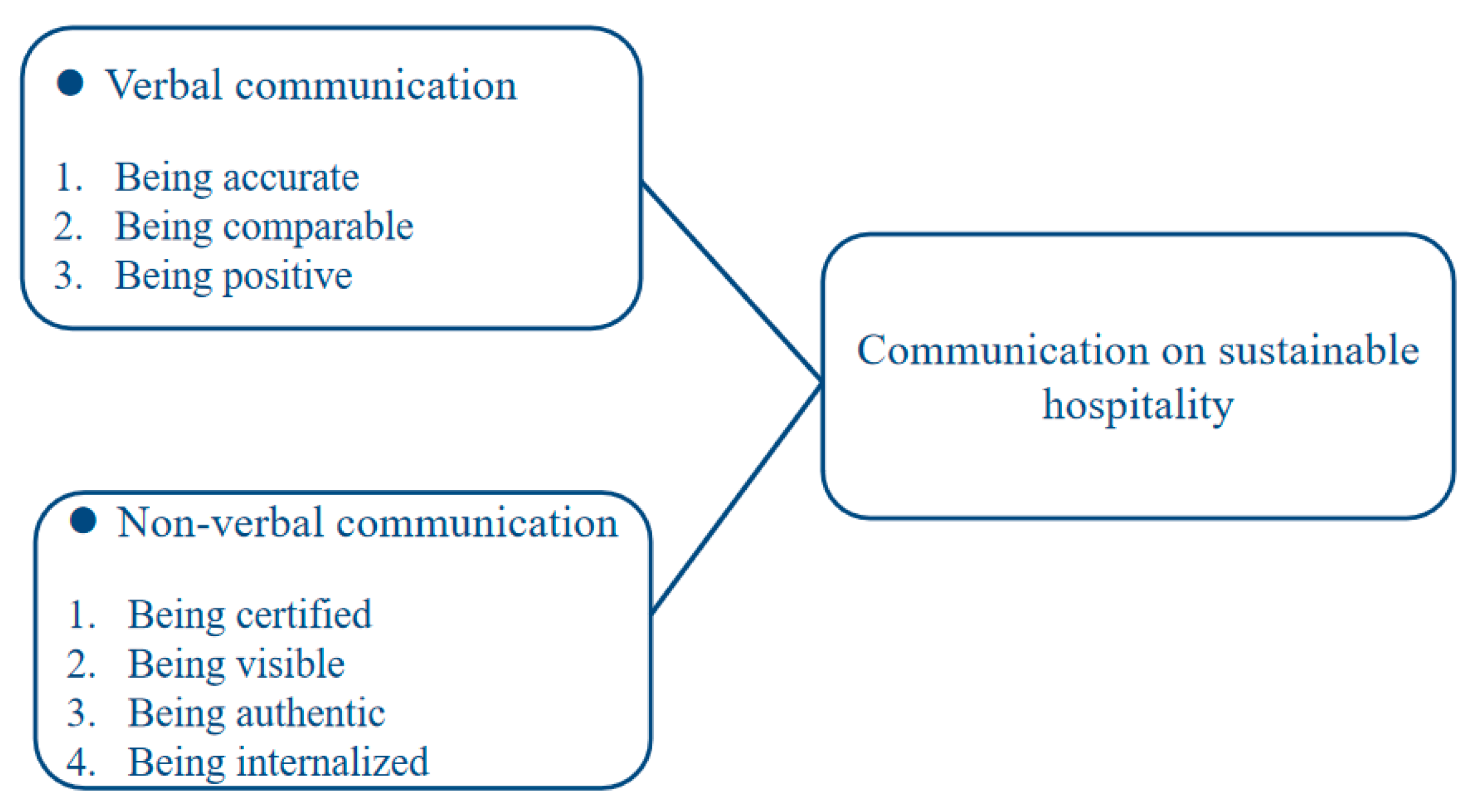

4.1. Verbal Communication

4.1.1. Being Accurate

“Claims being made must be verifiable so that the information communicated is accurate and not misleading or resulting in misinterpretation.” (P23)

4.1.2. Being Comparable

“What % energy and water reduction does your hotel/portfolio achieve compared to its relevant peers, and to past performance?” (P22)

“Communication on sustainability shall use data, baseline studies, and benchmark, allowing to measure evolution and prove the impact.” (P27)

4.1.3. Being Positive

“People who are spending a significant part of their savings to travel do not want to feel guilty about it.” (P19)

4.2. Non-Verbal Communication

4.2.1. Being Certified

“Certification and labels—whether legitimate or not—seems to be the marketing weapon of choice when it comes to communicating a hotel’s sustainability efforts.” (P26)

4.2.2. Being Visible

“The guest should see results of sustainable practices throughout the hotel, whether it is light sensors, passive shading, rainwater harvesting, use of native vegetation, protection of habitats, or locally sourced food and products.” (P29)

“Conscious consumers need transparency. Wayaj has an advanced travel carbon footprint calculator and footprint offsetting program.” (P11)

“We find that our stakeholders are willing to understand this, as long as we’re transparent about where we are on the journey, the challenges we face and what this means in reality.” (P1)

4.2.3. Being Authentic

“Every stay, a tree is planted. Provides a meaningful way for travelers to support the planting of trees/offset travel emissions while traveling.” (24)

“Being able to explain to the ‘informed traveler’ why you still have a menu item that is not the best available option from a sustainability perspective, will create a more authentic story that have your employees trained to inform your guest that you comply with this or that standard.” (P20)

4.2.4. Being Internalized

“The world is more transparent than ever and if you focus on your employees and suppliers, this, in turn, will support and ensure exactly the communication you are looking for.” (P21)

4.3. Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ge, H.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y. International alliance of green hotels to reach sustainable competitive advantages. Sustainability 2018, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospitality.net. Available online: Hospitalitynet.org/panel/125000036.html (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Buffa, F.; Franch, M.; Rizio, D. Environmental management practices for sustainable business models in small and medium sized hotel enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvelbar, L.; Grun, B.; Dolnicar, S. Which hotel guest segments reuse towels? Selling sustainable tourism services through target marketing. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booking.com. Available online: globalnews.booking.com/bookingcom-reveals-key-findings-from-its-2019-sustainable-travel-report (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Ettinger, A.; Grabner-Krauter, S.; Terlutter, R. Online CSR communication in the hotel industry: Evidence from small hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 68, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissen, F. Sustainable hospitality: A meaningful notion? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Raab, C.; Yoo, M.; Love, C. Sustainable hotel practices and nationality: The impact on guest satisfaction and guest intention to return. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Gursoy, D. Influence of sustainable hospitality supply chain management on customers’ attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 49, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.; Popovich, K. Understanding customer relationship management (CRM): People, process and technology. Bus. Pros. Manag. J. 2003, 9, 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltman, T.; Devinney, T.; Midgley, D. Customer relationship management and firm performance. J. Inf. Tech. 2011, 26, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnapureddy, S.; Priskin, J.; Vinzenz, F.; Wirth, W.; Ohnmacht, T. The mediating role of perceived benefits on intentions to book a sustainable hotel: A multu-group comparison of the Swiss, German and USA travel markets. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1290–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkes, C. Sustainability communication in tourism—A literature review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Diana, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, J.I. Sustainable communication. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2000, 78, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimara, E.; Manganari, E.; Skuras, D. Don’t change my towels please: Factors influencing participation in towel reuse programs. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, A.; Kamel, H.; Elbanna, S. Investigating relationships between stakeholders’ pressure, eco-control systems and hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 59, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, W. Environmental certification schemes: Hotel managers’ views and perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraj, E.; Matute, J.; Melero, I. Environmental strategies and organizational competitiveness in the hotel industry: The role of learning and innovation as determinants of environmental success. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Fu, X.; Cao, H.; Shen, Y.; Deng, H.; Wu, G. Energy performance of hotel buildings in Lijiang, China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X. A comparison theoretical framework for examining learning effects in green and conventionally managed hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.; Trang, H.; Kim, W. Water conservation and waste reduction management for increasing guest loyalty and green hotel practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Lo, A.; Yeung, P.; Hatter, R. Hotel ICON: Towards a role-model hotel pioneering sustainable solutions. Asia. Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Hall, C.; Ozanne, L. Hospitality industry responses to climate change: A benchmark study of Taiwanese tourist hotels. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Rajagopalan, P.; Lee, S. Benchmarking energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in Singpore’s hotel industry. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 4520–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Johnston, N.; Patiar, A. Coastal resorts setting the pace: An evaluation of sustainable hotel practices. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preziosi, M.; Tourais, P.; Acampora, A.; Videira, N.; Merli, R. The role of environmental practices and communication on guest loyalty: Examining EU-Ecolabel in Portuguese hotels. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lu, C. The relationship between CRM, RM, and business performance: A study of the hotel industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Integrating customer relationship management in hotel operations: Managerial and operational implications. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 24, 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, D.; Lancaster, G. The significance of CRM to the strategies of hotel companies. World. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2013, 5, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I.; Fong, D.; Law, R.; Fong, L. State-of-the-art social customer relationship management. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.; Au, N. Exploring customer experiences with robotics in hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2680–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Kleffner, A.; Bertels, S. Signaling sustainability leadership: Empirical evidence of the value of DJSI membership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellringer, A.; Ball, A.; Craig, R. Reasons for sustainability reporting by New Zealand local governments. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2011, 2, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, M.; Orindaru, A.; Pachitanu, A.; Rosca, L.; Caescu, S.; Orzan, M. Attitude evaluation on using the neuromarketing approach in social media: Matching company’s purposes and consumer’s benefits for sustainable business growth. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M. Strategic Communication for Sustainable Organizations: Theory and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R. Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S. Factors influencing the use of the World Wide Web for sustainability communication: An Australian mining perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelopo, I.; Moure, R.; Preciado, L.; Obalola, M. Determinants of web-accessibility of corporate social responsibility communications. J. Glob. Responsib. 2012, 3, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Roberts, R. Environmental reporting on the internet by America’s Toxic 100: Legitimacy and self-preservation. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S. Web based social and environmental communication in the Australian minerals industry: An application of media richness framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 25, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Olalla, A.; Aviles-Palacios, C. Integrating sustainability in organizations: An activity-based sustainability model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, O.; Melville, N.; Plice, R. Toward a sustainable email marketing infrastructure. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, C.; Godemann, J. Internet-supported sustainability reporting: Developments in Germany. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, G.; Font, X.; Nawijn, J. The power of persuasive communication to influence sustainability holiday choices: Appealing to self-benefits and norms. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A. Luxury hotels going green—The antecedents and consequences of consumer hesitation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1374–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezan, O.; Millar, M.; Raab, C. Sustainable hotel practices and guest satisfaction levels. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2014, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dief, M.; Font, X. The determinants of hotels’ marketing managers’ green marketing behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Elgammal, I.; Lamond, I. Greenhushing: The deliberate under communicating of sustainability practices by tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, J. Theorizing scenario analysis to improve future perspective planning in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A. Textual Analysis: A Beginner’s Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Cacciatore, M.; Liang, X.; Brossard, D. Analyzing public sentiments online: Combining human- and computer-based content analysis. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 406–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, D.; Chen, T.; Moles, R. Educational interventions on fever management in children: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyuga, E.; McCarthy, M. English and Russian vague category markets in business discourse: Linguistic identity aspects. J. Pragmat. 2018, 135, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.; Jones, E. Customer relationship management: Finding value drivers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossling, S.; Buckley, R. Carbon labels in tourism: Persuasive communication? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Randall, A. Selling climate change? The limitations of social marketing as a strategy for climate change public engagement. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, W.; Hsieh, M. Exploring how relationship quality influences positive eWOM: The importance of customer commitment. Total. Q. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 23, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, M.; Chin, T.; Fischer, J. Linking Halal food certification and business performance. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 1606–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Chandra, B. Hotel guest’s perception and choice dynamics for green hotel attribute: A mix method approach. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 77601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.; Jiang, Y.; Jha, S. Green hotel adoption: A personal choice or social pressure? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3287–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.; Murphy, P. CSR practices and consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1839–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D.; Han, H. Influence of environmental stimuli on hotel customer emotional loyalty response: Testing the moderating effect of the big five personality factors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G. Developing your company image into a corporate asset. Long Range Plan. 1993, 26, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, T.; Ulmer, R.; Snider, M. The compatibility of corrective action in organizational crisis communication. Commun. Q. 1998, 46, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, R. Du-Babcock, B. Language-based communication zones in international business communication. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2001, 38, 372–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedel, W.; Kamakura, W. Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Fridgen, J.; Stynes, D. Cohort segmentation: An application to tourism. Leis. Sci. 2003, 25, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Oh, H. Effective communication strategies for hotel guests’ green behavior. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L. Cultural differences between Mandarin-speaking tourists and Australian hosts and their impact on cross-cultural tourist-host interaction. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 42, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, M.; Madera, J.; Neal, J. Managing bilingual employees: Communication strategies for hospitality managers. World. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2011, 3, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktadiana, H.; Pearce, P.; Chon, K. Muslim travelers’ needs: What don’t we know? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Gender | Position | Base |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Vice president of a hotel group | UK |

| 2 | Female | Director of a tourism company | UK |

| 3 | Male | Senior staff of a hotel group | Germany |

| 4 | Female | Chief commercial officer of an environmental agency | US |

| 5 | Female | Founder of a sustainable hospitality consultancy | Germany |

| 6 | Female | Expert for sustainability communication | Switzerland |

| 7 | Male | Chief executive officer of an environmental consultancy | Thailand |

| 8 | Female | Chief executive officer of a hotel group | Peru |

| 9 | Male | Technology executive of a hotel consultancy | US |

| 10 | Female | Founder of an environmental agency | Germany |

| 11 | Female | Professor of tourism management | Spain |

| 12 | Male | Founder of a sustainability leaders project | Switzerland |

| 13 | Male | Chief executive officer of an investment consultancy | US |

| 14 | Male | Assistant professor of hotel management | Switzerland |

| 15 | Female | Director of a hotel sustainability consultancy | UK |

| 16 | Male | Associate professor of corporate social responsibility | France |

| 17 | Female | Chief executive officer of a hotel management consultancy | Germany |

| 18 | Female | Professor of tourism management | Netherlands |

| 19 | Male | Managing director of a technology company | US |

| 20 | Male | Senior research fellow of sustainable hotel management | Netherlands |

| 21 | Male | Managing director of an environmental consultancy | Germany |

| 22 | Male | Managing director of an environmental consultancy | UK |

| 23 | Male | Professor of hotel management | Germany |

| 24 | Female | Senior staff of an environmental consultancy | US |

| 25 | Female | Marketing director of a hotel | Austria |

| 26 | Male | Lecturer of hotel management | Germany |

| 27 | Male | Head of a hotel management consultancy | France |

| 28 | Female | Head of a hotel management consultancy | UAE |

| 29 | Male | Director of a hotel group | Germany |

| 30 | Male | Founder of an environmental consultancy | Australia |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, L.; Qian, J.; Chen, S.C. Effective Communication Strategies of Sustainable Hospitality: A Qualitative Exploration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176920

Shen L, Qian J, Chen SC. Effective Communication Strategies of Sustainable Hospitality: A Qualitative Exploration. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176920

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Leiyan, Jianwei Qian, and Sandy C. Chen. 2020. "Effective Communication Strategies of Sustainable Hospitality: A Qualitative Exploration" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176920

APA StyleShen, L., Qian, J., & Chen, S. C. (2020). Effective Communication Strategies of Sustainable Hospitality: A Qualitative Exploration. Sustainability, 12(17), 6920. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176920