1. Introduction

Since the emergence of the Internet, consumers have increasingly used this medium to search for information on multiple topics. For decision making as a consumer, the comments and opinions of other consumers and customers are highly appreciated and considered to be quite reliable. This type of communication (consumer-to-consumer or C2C) has become a critical element for service offerings, especially in the tourism sector. Tourist services cause uncertainties among potential customers because of their characteristics, such as the services and the distance between the buyer and the place of service production. Therefore, the study of this type of communication is essential for tourism businesses. Additionally, one of the elements of study is how and why comments on tourist experience are generated [

1]. This type of C2C communication is the essence of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) and an important subject of study [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The question often arises as to whether WOM and eWOM are the same, i.e., whether the two terms represent the same concept. The differences arise from the context in which they are developed. Based on contextualization, WOM is generated by an external stimulus (a question or in the development of a conversation). It is often related to customer satisfaction, and this often leads to confusion with customer loyalty. eWOM is generated by an internal stimulus (the need to express feelings derived from experience). This term is usually related to experiences which have impacted the individual (positive or negative). This means that the concepts WOM and eWOM depend on different interactions [

5].

In recent times, emotions and experiences have become widely expressed and highly relevant concepts in the study of consumer behavior [

6,

7,

8]. Actually, emotions are found in people’s behavior at all times [

6,

9,

10], and their study is essential for situations of hedonic consumption, such as tourism. Several authors [

11,

12] consider that cognitive models are tools with significant limitations, because they do not take into account the emotional component of the assessment of service provision [

6].

The desire to have exciting experiences is a fundamental element in explaining the motivations to travel for leisure reasons. The temptation to share experiences with other people after a trip is usually very strong. The role of emotions in tourism has received important recognition (e.g., [

6,

13,

14,

15]). These studies show emotions as an antecedent of satisfaction and behavioral intentions (e.g., [

16]).

The importance of emotions, customer satisfaction, and post-purchase behavior is widely recognized in the academic literature on tourism and hospitality, but there are still uncertain aspects regarding the possible relationship between these three concepts [

16,

17]. In some studies, there is a positive relationship between satisfaction and intention to recommend [

18,

19], but other authors have doubts about this [

17,

20,

21]. With the emergence of Web 2.0, word-of-mouth (WOM) has been surpassed and eclipsed by eWOM, but more studies on eWOM in the context of tourism are still needed [

3,

22].

The purpose of this paper is to examine the role of exceeding expectations in emotional experiences, customer satisfaction, and eWOM generation, in the context of lodging services. This sector has been chosen due to being the main element of the tourism product, and being able to specify the questions in a more specific service than the whole of a trip or destination. The objective is to know what leads consumers to leave comments on the Internet. This is a field which has not been studied in depth [

21]. The main objective of this paper is to determine the importance of exceeding the expectations of customers in the eWOM generation.

Sustainability in the business sector is defined as “a systematic business approach and a strategy which considers the long-term social and environmental impact of all economically motivated conduct of a company” [

23](p. 10). Yip and Bocken [

24] define it as “generating benefits by significantly reducing negative impacts on the environment and society” (p. 151). It should also be noted that unsustainable economic development impairs environmental and social sustainability [

25]. This is the reason why the underlying objective of this investigation is to find the most effective sustainable ways to achieve the objectives of tourism organizations. All this results in being able to develop its activities, under the paradigm of economic sustainability in the short, medium and long term. The economic sustainability which is highlighted in this work indirectly helps the social and environmental sustainability of the region in which organizations operate.

For this purpose, structural equation models (SEM) and a sample of 354 residents of the Maldonado-Punta del Este conurbation (Oriental Republic of Uruguay), asked about their last occasion in a hotel, were used. Punta del Este is an important tourist destination in Uruguay, and both cities form a continuum whose population consists of more than 100,000 residents. This document is divided into several sections: after this introduction, there is a literature review, where the state of the art in relation to the various causal relationships proposed is discussed; subsequently, there is a section where the methodology used in the analysis is presented and a section presenting the results of the analysis performed, indicating which hypotheses are rejected and which are not; the work ends with a discussion of the conclusions and limitations. The most notable one results in the importance of exceeding clients’ expectations to generate a positive emotional experience. Experience is fundamental to encouraging the generation of online comments.

2. Literature Review

Service quality is the starting point for achieving competitive advantages, differentiating the product and the company, enhancing the corporate image, and achieving customer loyalty towards the brand [

26,

27]. Clients perceive the service quality as a set of characteristics that are analyzed to perform a global assessment of the service [

28]. This consumer behavior implies that studies on the service quality are specified in a battery of questions, regarding different aspects that are important for consumers. SERVQUAL [

29] is the best known and applied scale for this type of disaggregated analysis. Previous studies have proposed sets of elements that are important for customers when they value the hotel quality [

27], with the importance of online customer interactions being remarkable [

30].

Sustainability in the business sector is defined as “a systematic business approach and a strategy which considers the long-term social and environmental impact of all economically motivated conduct of a company” [

23](p. 10). Yip and Bocken [

24] define it as “generating benefits by significantly reducing negative impacts on the environment and society” (p. 151). It should also be noted that unsustainable economic development impairs environmental and social sustainability [

25]. Taking into consideration the link between territory and the sustainability of organizations [

31,

32], organizations adopt sustainable behavior to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the territory where they carry out their activities. These actions result in a benefit (economic, social and environmental) in their environment. It should be noted that companies gain a more relevant role in the economic, environmental and social transformation in the geographical areas in which they work [

33]. This fact influences the increasing impact (both positive and negative) which organizations have in their environment, and the relevance that companies acquire in terms of sustainability in the territory where they are located.

In relation to stakeholders, it is worth highlighting that organizations take on a role in which their actions affect their perception. Moreover, [

34] highlights the great importance of the link between the adoption of sustainable practices and the fulfillment of the expectations of the organizations’ stakeholders. This author considers that, in order to counteract the negative effects on the territories in which they operate, companies should take into account the expectations of the stakeholders affecting them, not just domestic stakeholders. Furthermore, [

35] emphasizes that the attributes which make up the interests of stakeholders are different depending on the country. Therefore, guiding research on the satisfaction of stakeholder expectations, taking a set of attributes into account in the study of a territory, is of great relevance to sustainability in its three dimensions (social, environmental and economic).

Satisfaction can be defined as the result of a comparison between expectations and perception in relation to the service analyzed [

29,

36]. If one takes into account that expectations are the attributes that the consumer expects to find and, therefore, the list of elements to be taken into account in the quality evaluation, a direct relationship between quality and satisfaction is proposed in the definitions. The concept of satisfaction can be defined as the logical consequence of high levels of service quality. It has been widely demonstrated in the literature (e.g., [

27,

37]) that the quality of service has a direct and positive effect on customer satisfaction. In fact, it is usually defined as meeting the previous expectations of the consumer. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Service quality has a positive direct effect on customer satisfaction.

In recent years, there has been an increasingly abundant production of literature on the tourist experience, eclipsing studies on tourist service quality. The tourist’s emotional experience includes multiple elements: satisfaction with the service, pleasant emotions [

38], and memorable memories [

39], among others. This multiplicity of elements makes the consumer experience tremendously complex [

40]. In addition, it should be borne in mind that the methodology and design of the research adopted in each case generate different visions of this phenomenon. The consumer experience can be considered as all of the elements involved in the provision of the tourist service.

Therefore, a positive experience means exceeding the expectations of the consumer, and to match or exceed the expectations of consumers, all of the requirements expected by the customer must be met, representing parameters to be taken into consideration when measuring service quality. It should be noted that knowing and meeting consumer expectations is required, but not sufficient, for achieving a positive emotional experience. Determining customers’ expectations and when they are exceeding these expectations is very complex, because it depends on multiple aspects of the customers. Finally, it is the clients’ perceptions that determine reality, and the expectations which mark the difference between a quality and memorable experience.

All of this leads us to state that the service quality is the starting point, and a positive emotional experience is the consequence of overcoming what is understood as a satisfactory service. Based on this, it can be proposed that the service quality is an important and necessary background to positive emotional experiences. This leads to the proposal of the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Service quality has a positive direct effect on emotional experience.

The relationship between service quality and consumer satisfaction has been quite extensively studied (e.g., [

27,

41,

42,

43,

44]), but at present, the fulfillment of technical requirements is not good enough, and consumers already expect something else, mainly to surprise them. This forces the research field to move from the most technical elements to the most psychological and emotional aspects of the tourist service. Quite a lot of the literature supports the causal relationship between emotions, service evaluation, and behavioral intentions. Some studies on marketing (e.g., [

45]) and tourism (e.g., [

6,

16]) found a positive and significant relationship between these three concepts. It should be noted that the relationship between positive emotions and consumer satisfaction is well-supported in the existing literature (e.g., [

6,

17,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]), but some studies (e.g., [

19]) have found ambiguous results in the context of tourist destinations.

Therefore, although there are papers that support the existence of a significant causal relationship between positive emotions and consumer satisfaction (e.g., [

6,

17,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]), it is not yet possible to affirm that this causal relationship occurs in all types of sectors and contexts. Therefore, it would be interesting to consider the causal relationship between both constructs, and the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Emotional experience has a positive direct effect on customer satisfaction.

eWOM, also often referred to as online opinions, online recommendations, or online reviews, has gained importance with the emergence of new technological tools [

52]. Ref. [

3] (p. 461) define eWOM as “all informal communications directed at consumers through Internet-based technology related to the usage or characteristics of particular goods and services, or their sellers”. There is a growing interest in understanding the factors that determine eWOM generation and, due to its importance for the decision making of tourists, the tourism sector has shown great interest in understanding eWOM, as well as its causes and effects [

53].

Existing literature supports the existence of a causal relationship between positive emotional experiences and the intention to recommend [

54,

55,

56] and generate WOM [

45,

53], but has not yet been sufficiently analyzed in the tourism sector. Even so, it should be noted that tourism companies are clear about the importance of positive experiences of tourists [

48], due to their potential for generating positive comments and, consequently, generating a reputation for the company and its brand. In the case of eWOM, there are still few investigations that have addressed the factors that generate comments [

21].

Some tourism entrepreneurs believe that the relationship between experience and eWOM is so close that, in reality, eWOM is a component of experience linked to individual self-realization. This close relationship is only a guess for some people, but a causal relationship cannot be ruled out [

45]. In any case, a causal relationship between both constructs is more than plausible. This leads us to propose the next hypothesis (although it mentions emotional experiences, it should be understood that reference is made to positive emotional experiences):

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Emotional experience has a positive and direct effect on the eWOM generation.

Analyses of the relationship between satisfaction and the generation of eWOM are still scarce, and the results are not conclusive [

19]. Some authors have not found a clear and significant relationship between satisfaction and eWOM [

17,

20,

21,

57], but they have not clearly rejected it either. This situation forces researchers to continue working on the analysis of this causal relationship, especially in the context of hospitality. At present, the comments limited to indicating that the service received has been correct represent the minority and, normally, people only leave comments if there is something unusually positive or negative. However, despite this fact, and the previous literature, it cannot be ruled out that there is a significant relationship between customer satisfaction and positive eWOM generation, which leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Customer satisfaction has a positive and direct effect on eWOM generation.

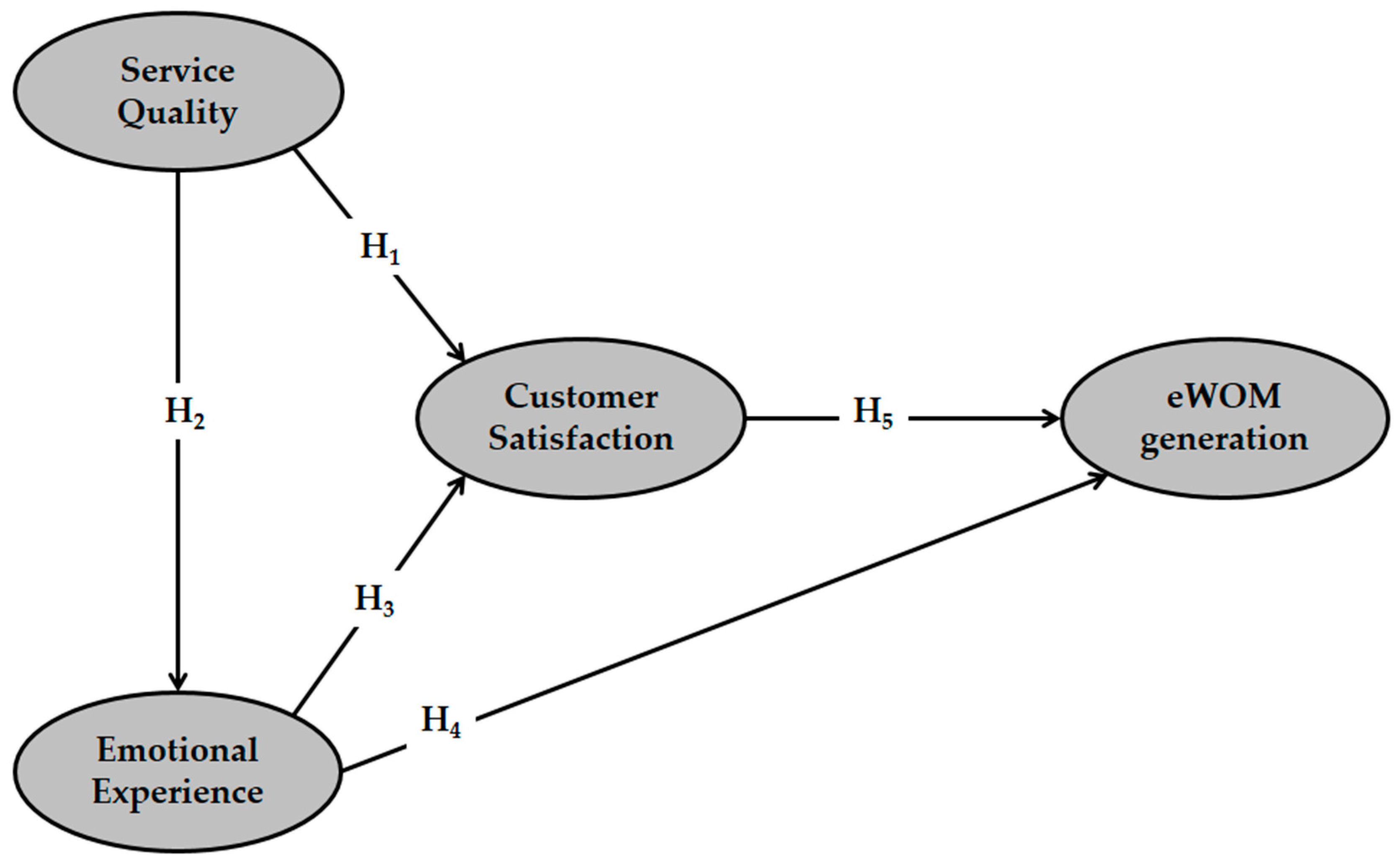

The hypotheses presented configure a causal model composed of three independent variables (quality, satisfaction, and experience) and a dependent variable (eWOM), which have been analyzed in previous investigations [

58]. These causal relationships make up the initial causal model (

Figure 1).

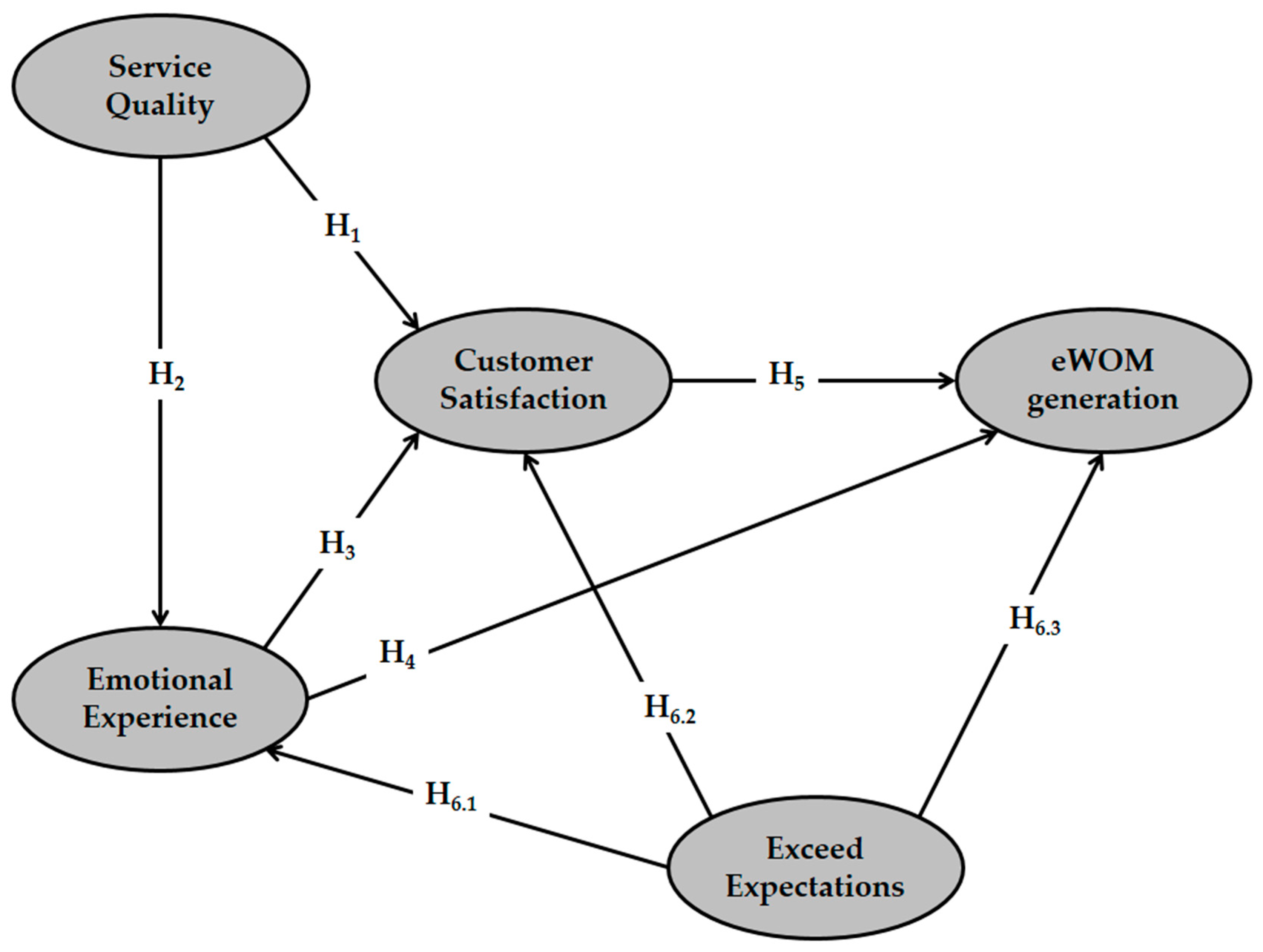

In the academic literature, the importance of exceeding customers’ expectations in the definition of various concepts has been mentioned on several occasions. Introducing this concept—exceed expectations—as an explanatory variable is the main objective of this research paper. It should be remembered that experiences include multiple elements [

38,

39,

40]. Despite this difficulty, in the tourism sector, positive experiences can be described as services that exceed expectations (personalized, innovative, surprising, etc.)This implies that the quality of service (fulfillment of the client’s expectations) can be eclipsed as an explanatory variable of emotional experience due to exceeding expectations.

Customer satisfaction is a comparison between expectations and the perceived service [

29,

36]. Therefore, exceeding expectations is part of the definition, and a very important explanatory variable of customer satisfaction.

Comments that do not express extreme assessments represent the minority in the online environment, although this may change in the future. There is a possible explanation for this: WOM is the result of searching for a topic of conversation or the answer to a question or doubt put forward. eWOM implies a dissemination of information without a specific addressee, and with the sole purpose of communicating something that has surprised somebody, either positively or negatively. This leads us to propose an explanatory variable of eWOM generation, which is the concept of exceeding expectations. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Exceeding expectations has a positive direct effect on emotional experience, customer satisfaction, and eWOM generation;

Hypothesis 6.1 (H6.1). Exceeding expectations has a positive direct effect on emotional experience;

Hypothesis 6.2 (H6.2). Exceeding expectations has a positive direct effect on customer satisfaction;

Hypothesis 6.3 (H6.3). Exceeding expectations has a positive direct effect on eWOM generation.

When adding exceeding expectations as an explanatory variable, an extended causal model is developed (

Figure 2).

3. Methodology

In order to verify the hypotheses in this investigation, a questionnaire was drawn up based on the literature review, and adapted to the object of study and the research work to be carried out [

6,

11,

17,

27,

51,

59,

60]. The questionnaire was divided into different blocks, with one being the socio-demographic information. The remaining blocks collated information related to the constructs investigated using a 5-point Likert scale: service quality, customer satisfaction, emotional experience, eWOM generation, and exceed expectations. The 5-point Likert scale is very common and traditional in tourism and hospitality studies.

The instrument used for collating information in this investigation is a reviewed and improved version implemented in previous studies [

3]. Prior to fieldwork, the questionnaire applied to this research was reviewed by several experts in the marketing area. It was then tested by a small sample of university students, in order to check whether the questions were understood correctly. Once these previous checks were carried out, the small improvements in the questionnaire were incorporated, and subsequently, the information was collated. Due to the fact that this questionnaire was designed to maintain the interviewee’s anonymity, authorization or supervision were not necessary on the basis of ethical issues.

The fieldwork consisted of personal interviews with people living in the Maldonado-Punta del Este conurbation. These respondents were asked if they had stayed in a hotel in the last six months, and if this were the case, they were asked to base their answers on their last hotel stay, regardless of the location and category of the hotel. This is a convenience sample, but demographic aspects of it were controlled to avoid serious biases in the profile obtained. It must be considered that the representativeness of the sample is less relevant in causal investigations, and a sampling for convenience does not cause any problems for the validity of the results. The sample size required to test the models raised in this work, with perfectly independent variables and assuming the power of 0.80 and an Alpha of 0.05, is 66 for Model 1 and 76 for Model 2for a medium effect size [

61,

62]. Even considering that this investigation would be correctly developed by obtaining an adequate sample in the range of these minimum parameters, the aim of this work was to obtain a sample of more than 300 interviewees. This is the reason why more intense work was undertaken in order to obtain a larger sample size.

In order to verify the hypotheses, the partial least square (PLS) technique based on the SEM methodology was used. The software used was SmartPLS [

63], being the most suitable for this investigation [

64]. A normal distribution is not assumed by the PLS-SEM technique, and this implies that parametric tests are not applicable for significance levels analysis, but there are other alternative and reliable non-parametric tests for this purpose. Specifically, PLS-SEM uses non-parametric bootstrapping for significance levels analysis of the path coefficients [

65,

66]. In order to determine the t-student, the relationship given by [

64] was relied on, and the calculation of T and errors was based on [

67].

The use of the non-parametric statistical method PLS-SEM in academic research has continued to increase since the 1990s [

68]. PLS-SEM has been specifically used in investigations on economic sustainability [

69,

70,

71], social sustainability [

69,

70] and environmental sustainability [

69,

70] in the context of organizations. In addition, it is common to use this methodology in studies on management [

68,

72], marketing [

73,

74,

75,

76] and tourism [

77,

78].There is analysis implementing this statistical method (PLS-SEM) in the context of tourist destinations [

79], hotel management [

80,

81,

82] and eWOM generation [

3,

45]. Currently, models of structural equations are the most commonly used methodology for causal analysis in social sciences, and the PLS technique is becoming more relevant in research, due to the advantages of their use.

4. Results

The total number of valid questionnaires was 354. The profile of the informant is that of a person who stayed in a hotel no later than six months prior to the survey. The informant provided information regarding their last stay in a hotel.

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic profile of respondents. The respondents were mainly young people, students, and others who had higher education levels. It should be noted that this socio-demographic profile is characterized by a greater frequency and propensity to travel than other socio-demographic profiles. The sample obtained and analyzed in this paper is characterized by traveling one or two times each year (57.34%), although there were a few who travelled very frequently, that is, six or more times a year (11.58%).

Pleasure was the main reason for travelling (74.29%). The duration of the stay corresponds to a maximum of one week (74.30%). The informants were tourists who were staying in the hotel under study for the first time (76.27%). The majority of the respondents were staying in urban hotels (63.84%). A higher percentage were in 4-star hotels (33.90%), compared to a lower percentage of informants staying in 3-star hotels (23.16%), and to a lesser extent, tourists staying in 5-star hotels (17.51%).

First, the measurement model was reviewed, by analyzing four different parameters. All of the items met the requirement established by [

83], with each of their weights being greater than 0.707. Cronbach’s alpha [

84] and the composite reliability [

85,

86] were used to measure the construct’s reliability. The results obtained are quite acceptable (

Table 2), and their reliability is greater than 0.820 [

87].

The convergent validity was reviewed through the use of average variance extracted (AVE). In order to verify whether the results were indeed adequate, the AVE was calculated on the basis of [

88] conceptualization, taking into account that the values must be greater than 0.5 [

86,

88]. As can be seen in

Table 2, the latent variables’ values meet the requirements, and, specifically; all of the AVE values are superior to 0.580 for the raised models.

Following the two approaches to calculating the discriminant validity in PLS, the contributions and requirements were taken into consideration, based on Anderson and [

85,

89]. After completing the above verifications, scales were debugged where necessary.

Table 3 shows the measurement model that was finally proposed.

Following the measurement model, an analysis of the structural models was carried out for obtaining the value of R

2 (

Table 2). The case of customer satisfaction (0.688 for Model 1 and 0.721 for Model 2) is especially significant, and the eWOM generation (0.225 for Model 1 and 0.228 for Model 2) is not very significant. Exceeding expectations was incorporated into Model 2 and improved the explanatory capacity of the model, especially that of emotional experience (R

2 increases to 0.279). This first data set can already serve as an indication of the importance of this new variable (exceeding expectations), since it improves the explained variable of all the dependent variables, especially the emotional experience. Therefore, exceeding customer expectations is a very important, or even fundamental, component of the definition of positive emotional experience itself (remember that this paper always refers to positive experiences). Although it is not analyzed in this paper, it is more than possible that, if the service does not meet the customer expectations, an effect of similar importance occurs, but in the opposite direction, generating a negative emotional experience.

The initial causal model (Model 1) was analyzed, and all causal relationships were found to be significant (

Table 4). Service quality has a very strong relationship with consumer satisfaction (β = 0.629), and this is significant at the level of 0.001 (H1). This causal relationship is very classic and, sometimes, there are doubts as to whether the correlation between both concepts is due to their strong causal relationship or to confusion between the concepts by the interviewees. Service satisfaction can be considered as the relationship between previous personal expectations and the personal perception about the service received. In this case, there is talk of a “satisfied customer” if the post-service perception matches or exceeds previous expectations, and a “dissatisfied customer” if the perception is clearly below expectations. The risk of confusion between scales is possibly due to the fact that the service quality measures the elements that make up the service, in relation to the experience and expectations, and satisfaction is a global evaluation of the service.

Service quality also has an important (β = 0.603) and significant relationship with positive emotional experience (H2). This causal relationship is not as studied, and surprises with the values obtained, since they are quite high. It seems obvious that service quality is a necessary element for positive emotional experiences, but given the concepts that are often used to describe experiences, it is not enough, and there must be other important elements that explain the consumer experience.

Emotional experience has a positive (β = 0.282) and significant effect, at the level of 0.001, on consumer satisfaction (H3). It seems logical that consumer satisfaction has an important emotional component, and not only depends on “technical” elements, such as those measured with the service quality. It must be remembered that the subjectivity in multiple aspects of people’s lives and the enjoyment of services is one of the most important aspects. eWOM generation is influenced very positively (β = 0.595) and significantly, at 0.001, by emotional experience (H4), and negatively (β = −0.234) by consumer satisfaction (H5), although this last causal relationship must be excluded, due to the lower level of significance (0.05) and the inverse sign of the causal relationship.

Subsequently, the extended causal model was analyzed (Model 2), adding exceeding expectations as an explanatory variable (

Table 4). Through the analysis of Model 2, we intended to determine how the new variable affects the dependent variables and the causal relationships that do not directly depend on the new variable, when comparing Model 2 with Model 1. It should be remembered that statistical software does not unquestionably demonstrate the casual relationships and actually analyze the correlations, providing the best solution to the data and parameters marked before the analysis. This implies that the proposed causal model partially determines the solution provided by the statistical software. When comparing models 1 and 2, and the differences that occur, it is possible to find out how the absence of the variable exceeding expectations affects the result. Hypotheses 1 and 4 show results similar to Model 1 (

Table 4), but with slightly lower values. Hypothesis 5 also exhibits similar results to Model 1, since the improvements are minimal. The most important change occurs in the causal effects proposed in Hypotheses 2 and 3, since they go from clearly significant to non-significant. This great change in the result of the two hypotheses shows the importance of not excluding relevant variables from the models analyzed using statistical software, and how this can change the conclusions of a paper. In spite of the literature that supports Hypothesis 3, these results indicate that works such as those of [

19] would be right in questioning the existence of this causal relationship.

Of the three causal relationships added to the model, two are significant and one is not significant (

Table 4). Exceeding expectations has a very important (β = 0.723) and significant effect on emotional experience (H6.1), as suggested by the literature [

39], and a significant positive (β = 0.335) effect on customer satisfaction (H6.2), which is an expected result given the concept definition [

18,

70]. Note that the adoption of certain sustainable practices which fulfill the expectations of stakeholders and are implemented in the organization, end up affecting the territory, and consequently end up contributing to economic, social and environmental transformation [

33]. Exceeding expectations does not have a significant effect on eWOM generation (H6.3). To better understand the causal model results, it is necessary to review the total effects (direct and indirect) of independent variables on the dependent variables (

Table 5).

5. Discussion

Summarizing Model 1, four causal relationships had positive and significant effects, as indicated in the scientific literature [

6,

16,

17,

27,

37,

41,

42,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

54,

55,

56,

58]. A negative causal relationship was obtained between satisfaction and eWOM, with a lower-than-expected level of importance. This result is not surprising if one takes into account that no significant causal relationship [

21] or inconclusive results [

17,

19,

20] were found in previous studies. The negative sign of the causal relationship possibly indicates that online comments are only made if the stay has been unsatisfactory. In any case, this only represents a future hypothesis in a very primary state.

Customer satisfaction is determined by the service quality (meeting expectations), as previous literature indicates [

27,

37], and, to a lesser extent, by exceeding expectations. These causal relationships allow us to explain a high proportion of variance of the dependent variable, and coincide with the traditional definition of customer satisfaction [

58,

90].

Table 5 recalls that consumer satisfaction is due to the fulfillment of expectations (optimal service quality) and something else (exceeding initial expectations, that is, surprising the hotel guest), with both elements representing the essence of the classic definition of consumer satisfaction. Adopting sustainable practices in companies, which pursue the fulfillment of consumer expectations, will benefit the organization and the territory in which they operate.

It is possible to explain a high proportion of variance of the emotional experience by exceeding expectations, indicating that exceeding customer expectations is the fundamental element to generating positive and memorable emotional experiences. In the theoretical and academic field, it is possible to discuss concepts and their definitions widely, but in the practical and business field, clear definitions and easy translation into concrete actions are necessary. That the main component of the positive emotional experience is exceeding expectations (expectations defined as technical parameters) clarifies the company’s strategy. Even so, the transfer to concrete actions is not easy, because exceeding expectations forces us to perfectly know the consumers’ expectations, and continuously innovate in terms of service provision (an innovation is surprising and impressive in the first few occasions, but ends up being an element of the client’s expectations that must be met to reach a minimum). Some entrepreneurs define luxury as exceeding what is expected by the client (the product has everything the customer expects and something else that surprises them), intuiting the result of this paper. If the client includes sustainable attributes in order to meet their expectations, this will involve companies implementing actions of this typology, and consequently these action affect the destination.

eWOM generation owes its greatest effect to the emotional experience, as the literature suggests [

45,

53,

54], and the direct causal relationship of exceeding expectations is not significant. It should be noted that there is an indirect effect of exceeding expectations on eWOM generation, mediated by emotional experience, which is considerably important (β = 0.376) and significant at the level of 0.001. Therefore, there would be an important effect of exceeding expectations on eWOM generation, but it would be indirect and not direct, as hypothesis 6.3 proposed. In the research for an explanation of eWOM generation, emotional experience cannot yet be eliminated as the main causal variable, but it is possible that the positive emotional experience can be replaced by its main components, including exceeding consumer expectations. It would be necessary to find the element that makes exceeding expectations a positive, exciting, and memorable experience for consumers. Therefore, adding sustainable attributes to these experiences, however small they are, will be beneficial for the client in particular, and in general, for all affected stakeholders, organizations in which they are implemented, as well as the environment in which the activity is carried out.

It should be noted that, from the comparison of the two models (initial and extended), the importance of not excluding potentially important variables in the causal models analyzed is observed. In this case, when adding a new explanatory variable, several previously important causal relationships become non-significant in the extended model, questioning the results of previous studies. In the case of eWOM generation, the variance explained is low, and this indicates that more in-depth studies are needed, which raise new variables or causal relationships, to improve the understanding of online comments made by customers.

6. Conclusions

The scientific study of customer experiences and eWOM has been very important in recent years, but of great difficulty when dealing with affective elements rather than cognitive elements. Based on the results of this investigation, it is observed that exceeding expectations is very important for customer satisfaction and experience. Indirectly, it is also very important to exceed expectations for eWOM generation.

Frequent and knowledgeable customers have already discounted the fulfillment of the expected requirements. This is exposed in the lack of significance of the causal relationship between service quality and positive emotional experience, and in the negative sign of the causal relationship between customer satisfaction and eWOM generation. Company and destination differentiation are seen as the offered elements that go beyond what is expected, taking into account that the clients are increasingly more experienced and expect more. In this context, new technologies are essential to knowing customers’ expectations, in order to ensure compliance, start initiatives of co-creation of value which are highly valued by customers, and predict the success of innovative initiatives that would seek to surprise the customer.

Parallel to the increase in customer knowledge, there has been an evolution of hotel companies and consolidated tourist destinations towards a range of high-end, four- and five-star hotels. These hotels are defined by the entrepreneurs themselves as the compliance (4 stars) and improvement (5 stars) of expectations of the most expert and trained clients. This definition, which is apparently simple, is complex to carry out, and requires a continuous process of improvement of the establishments and services offered, based on the accurate and updated information of current and potential customers. In this context, the luxury (5 stars or 5 stars G.L.) is to know the customers and exceed their expectations, taking the most experienced customers as a reference. This indicates that hoteliers already sense the importance of experiences and expectations in their activity.

In the case of hotels, innovations that surprise guests and exceed their expectations may come from the development of new technologies applied to rooms or common areas, but also from small details in the reception, room service, complementary services, or common areas. A characteristic of people is that, sometimes, they are more surprised and pleased with a small detail (a towel, some flowers, a cordial greeting, etc.) than great innovations that involve large investments. Therefore, the key to exceeding expectations often lies in small details that do not require large costs.

Knowing how a customer behaves and the importance of exceeding their expectations is fundamental to the economic sustainability of companies, as well as for tourism regions. If the customer is more than satisfied, they will comment on the internet, which in turn, will attract more customers. Moreover, this may have an impact on the possibility of the customer repeating his/her experience, making it easier for economic activity to continue in the long term. If the tourism sector is sustainable and prosperous, a particularly important foundation is established for the social well-being and sustainability of the local community. In addition, it should be noted that knowing the importance of surprise and small details to exceed customer expectations and trigger the causal effects exposed, makes it possible to generate an economic improvement with a minimum consumption of resources. This, in turn, results in the greater environmental sustainability of the company, as well as the tourist destination.

This work is developed on the basis of the research of a case study; a research method which is repeatedly applied in the field of social sciences. However, it should be borne in mind that, although the results from Uruguay relate to a specific geographical area, they can be extrapolated to other tourist regions, especially if they have similar cultures.

Although the analysis refers to hotel and business implications that have also been produced by thinking about the accommodation establishments, the conclusions and implications are easily adaptable to other areas where it is considered that the emotional experience is important, for example, restaurants, nightlife establishments, transport services, or tourist destinations as a whole. In fact, all sectors which have a high intangible component in their products, especially in the context of leisure and tourist services, are capable of applying these conclusions.

Many new investigations are still required in multiple regions and sectors of the world to improve the understanding of concepts, such as customer experience and eWOM, taking into account new variables and improved causal models. Specifically, components analysis of the emotional experience needs further development, until it is possible to replicate its effect on the generation of eWOM with a composition of other variables with a more concrete definition, and until it is applicable to the practice of tourism and hospitality management. It would also be appropriate to repeat the study, but taking the negative emotional experiences as a reference, in order to know if the behavior is similar or differs. In addition, it would be of great interest to develop scales that serve to measure both positive and negative experiences.

In this case, it has been proven that, by adding a new variable to the model, previously important and significant causal relationships become non-significant. It is essential to find important causal elements to determine human behaviors. This entails the difficulty of determining all variables with potential causal effect. The difficulty of the analysis of excessively complex models also becomes a factor which requires a gradual process in the implementation of new variables, or the elimination of variables that have become irrelevant. This work provides knowledge in this development. It determines the importance of exceeding the expectations of the customer/tourist, to determine their experience, as well as their satisfaction with the service received.

The tools of statistical analysis commonly used allow the best solution to be found for a proposed model, given a database, but they are limited to determining if the proposed model is good or has deficiencies. They also do not allow it to be determined whether a sample database is representative of the entire population or only represents a special and limited situation. It should be noted that, in causal studies, the representativeness of the sample is not important, however, the variability of behaviors within the sample is, and in some cases, experiments are used on students or Mechanical Turk. These limitations make multiple studies necessary before considering a true or false theory or definitive hypothesis.

In this study, the existing limitations are the same as exposed before: the sample analyzed includes residents of a specific region who were asked about a recent hotel stay; the causal model can be extended or modified, giving different results, as shown by the comparison of the two models analyzed. In future studies, customers from different regions should be analyzed, with different tourist services and different degrees of Internet use. In addition, new explanatory variables and causal relationships must be considered.

This case study is applicable to different regions in the country, and in other countries with a similar culture. This research can be replicated in different companies, sectors, and destinations, by making small adaptations to the questionnaire. It should also be considered that the findings of this work provide valuable knowledge to have a greater understanding of customer expectations for the management of the tourist destination, as well as for academics. The findings of this work demonstrate that the customer expectation generates positive implications (economically), in the destinations covering the different areas. That is the reason why, following the comparative line with other countries replicating this study will provide relevant data to the implementation of an appropriate strategy of sustainability in the tourist destination. In addition, our findings can contribute to political implications; therefore, information can be available to be able to build and implement policies to attract clients (tourists) to the destination, based on sustainable guidelines. This means contributing to global strategies which will affect the destination in question, in order to prioritize differentiating strategies over other competitive destinations.

The implicit limitation of the tool used for statistical analysis must also be remembered. An analysis by experiments in a controlled situation would be the most ideal approach, and is recommended as a future confirmatory analysis. However, the technique used, through the use of structural equation models and PLS for analysis, is widely used and valid for an exploratory study that seeks to determine the importance of incorporating a new variable into a model, as is the case here.