Abstract

This study investigated the drivers of job satisfaction in the Alpine tourism industry. Intention to work in the profession in the future and training satisfaction were also examined. A total of 316 employees in two Alpine tourism regions were interviewed by means of a questionnaire and asked about the factors influencing their job satisfaction, their intention to remain in the sector, and their satisfaction with training. The results reveal significant differences between the two regions in the dimensions of appreciation, international job opportunities, compatibility of family life and career, workplace climate, working hours, and remuneration. The findings also highlight differences in training satisfaction and intention to remain in the job. These regional differences provide important insights into job satisfaction and the influences upon it, from which various approaches to pursuing sustainable development potential can be derived, including personnel management, reduction of employee turnover, and appreciative corporate culture towards guests and employees as well as image cultivation among the general public.

1. Introduction

During the 2019/20 winter season, the lack of skilled personnel in Alpine tourism, especially in the catering and hotel industry, was evident. In a survey conducted by the Austrian Federal Economic Chamber, more than 80% of the companies surveyed (N = 200) saw the availability and qualifications of employees as competitive factors in Austrian tourism, and approximately 60% described these as a challenge for recruitment [1]. Furthermore, 85% said that the need for qualified specialists will become an important issue in the coming years [1] though very few (2%) said they placed a strategic development focus on this [1].

A study by the Munich University of Applied Sciences and the personnel service provider GVO addressed the difficult situation in the job market for gastronomy professionals. The results indicate that vacancies are more difficult to fill than they were only a few years ago. The possible reasons cited were demographic developments and the modern employee’s expectations of the workplace, including a demand for one’s personal development and a good work–life balance [2].

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the future of Alpine tourism has been uncertain. Alpine tourism depends on mainly European travelers as well as the willingness to travel and the economic potential of guests in important countries of origin (e.g., Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom). A sharp decline in Alpine tourism is expected in the short to medium term. If a quantitative decline in overnight stays is assumed, there is likely to be a strategic shift in the industry towards higher quality or increased added value. As a result, the question of how to attract and retain well-trained, local, skilled personnel will become yet more important. The present study reveals that job satisfaction is one critical factor in this respect.

Compared with other sectors, the hospitality industry tends to experience very high levels of fluctuation [3], creating additional costs of millions of euros each year [4]. Companies in the hospitality industry deal with this issue on a daily basis [3]. Stress, overwork, and interpersonal tensions in the workplace are all associated with lower job satisfaction and higher turnover [5]. Furthermore, other factors, such as the rapid growth of the tourism industry and the high expectations of young workers, are also partly responsible for lower job satisfaction and high turnover in the tourism sector. Higher turnover is expected among employees who are more specialized or more difficult to find and who require special training [3]. Avoiding high staff turnover is particularly important in regions characterized by an aging population, as it is particularly difficult to find replacements [6].

Since job satisfaction fosters a sustainable workplace, it is an important part of a long-term sustainable organization [7,8]. Among other things, job satisfaction has the potential to reduce high staff turnover and promote loyalty, thereby having a positive impact on sustainable development at the company level [9]. When turnover is reduced, companies experience improvements in customer service quality and business performance [10]. The positive influence of job satisfaction on product and service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer relations [10,11] has the potential to promote sustainable development beyond the company level on the regional and destination level, as value creation and a source of economic prosperity for the local population can be ensured. Analysis of the factors that influence job satisfaction aims not only to reduce employee turnover but also to secure young talent for careers in the tourism sector. Alpine regions have been experiencing a growing shortage of skilled tourism-sector workers for many years. Three factors are at work here: (1) increased employment in the tourism industry (e.g., because of growth especially in Alpine tourism), (2) reduced numbers of trainees (e.g., because of demographic effects and critical public opinion), and (3) decreased willingness on the part of graduates to work in tourism professions (e.g., because of more attractive job alternatives in other professions or industries).

1.1. Background

For this study, graduates and/or professionals in the hospitality industry in South Tyrol and North Tyrol were interviewed in 2018 and 2019. These two regions account for a total of 83 million overnight stays. Thus, it is obvious that, despite low growth rates, the tourism sector is of real economic importance for both South Tyrol and North Tyrol. The regions are similar: both are characterized by the dominance of small and medium-sized family businesses, low academicization, and a trend towards greater comfort (hotel categories) [12]. Furthermore, the two regions are equally tourism-intensive (measured by overnight stays per inhabitant) but differ in their overall seasonality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structural tourism data for North Tyrol and South Tyrol (Source: Land Tirol [13], ASTAT [14]).

Moreover, significant differences exist in terms of the variance in tourism intensity, as measured by the 50 most tourism-intensive municipalities in North Tyrol and South Tyrol (Table 2).

Table 2.

Variances in tourism intensity in South Tyrol and North Tyrol (Source: Land Tirol [13], ASTAT [14]).

1.2. Research Objective

In the literature, job satisfaction is shown to be an essential personnel policy prerequisite for a sustainable quality and success strategy. Previous research has focused on the importance of appreciation and professional image for job satisfaction in the industry (e.g., [15]). Heimerl et al. [15] show that there are significant differences between the two regions studied in terms of perceived appreciation by supervisors (Δ = 54.8%) and guests (Δ = 41.3%) and also in the image of residents (Δ = 44.5%). This leads to the assumption that there are significant differences in perception between the two regions in relation to other factors. The present study expands on this insight and investigates further influencing factors, with intention to work in the tourism profession and satisfaction with the associated training investigated as reflective of job satisfaction. These results are then discussed in relation to sustainable development issues. Thus, four questions arise:

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of working in the hospitality industry?

- Do the respondents intend to work or continue working in the hospitality profession in the future?

- How satisfied are the study participants with their choice of apprenticeship?

- To what extent can job satisfaction promote sustainable development issues in the hospitality industry?

This study contributes to the literature on job satisfaction in the hospitality industry and offers new insights into the impact of various influencing factors. Furthermore, the study includes the intention to continue working in the tourism profession and satisfaction with one’s apprenticeship as essential outcomes of job satisfaction. The study also broadens the perspective in terms of job satisfaction and sustainable development issues.

2. Literature Review

Job satisfaction is an attitude toward work [16]. It is a relatively stable value system of operational conditions that lasts for a long period [17]. It is an attitude that influences one’s emotional reaction to work, opinions about work, and willingness to behave in a certain in regard to work [18]. Job satisfaction is not a simple response to the objective work situation of the employee, but rather it reflects a subjective perception of one’s job [19]. Locke [20] describes job satisfaction as a pleasant emotional state, reflecting the assessment of how the employee’s work role supports their values. Satisfied employees record fewer absences, less fluctuation, and lower sickness rates. Kong et al. [21] cite factors at the individual, organizational, social, and psychological levels as key influencers of job satisfaction in the hospitality industry. According to Kong et al. [21], the key results of job satisfaction are a strong organizational attachment and intention to stay.

Job satisfaction is seen as particularly important for the sustainable development of workplaces and entire organizations [7,8,9,11,22]. Several approaches to promoting organizational sustainability are discussed at the strategic level [7]. A particularly common approach is “sustainable leadership”, which aims to balance people, profits, and the environment to foster corporate longevity through the application of appropriate management practices, taking a holistic approach to organizational sustainability [7,22,23]. The concept of “sustainable leadership” thus includes the triple-bottom-line approach [7,22,23,24] and therefore has a multifaceted effect on sustainable development, not only in terms of job satisfaction but also, for example, in terms of sociocultural and environmental concerns. Especially in rural regions with great natural and environmental value, all dimensions of sustainability are important concerns, as tourism poses great challenges in terms of ecological and sociocultural aspects [25].

As issues of sustainability become more and more important, the strategic integration of objectives of all three sustainability dimensions in organizations increases [9,11]. Integration difficulties exist in particular in the measurability of sustainable development through the adoption of an appropriate set of key performance indicators (KPIs) [11]. Various studies have dealt with sustainability KPIs and their usefulness [11,26]. Job satisfaction is regarded as a KPI for sustainable enterprises [22] and for implementing sustainable strategies [11]. According to Azapagic [27] and Hristov and Chirico [11], job satisfaction belongs to the social sustainable strategic goals, and the employee satisfaction rate serves as a KPI, which is determined using questionnaires. Gabcanova [28] considers, among others, employee turnover and training hours per employee as KPIs on a human resource level.

It remains open to debate which factors really are drivers of job satisfaction in the hospitality industry and to what extent. In line with the “sustainable leadership” approach [22,23], enterprises that actively care for the well-being of their employees and offer the opportunities for independent and meaningful decisions tend to see higher levels of job satisfaction [10], while an employee who is not satisfied with their work is more likely to quit [29]. McPhail et al. [10] conducted a factor analysis of 9000 employees in the global hospitality industry and identified three groups of factors related to job satisfaction. The first of these was career development, with employees found to value training and development for their professional advancement. The second was control and diversity, including the opportunity to use one’s initiative, variation in tasks, contribution, and independence; the third was social relationships (teamwork, friendship, mutual respect, and appreciation from others). These three dimensions were all found to have positive and significant effects on overall job satisfaction, with employees needing to feel that their workplace offers a wide scope of work, provides opportunities for self-development, and constitutes a friendly environment [10].

Hotel companies that actively care for the well-being of their employees tend to generate higher levels of job satisfaction [10,29]. Likewise, the corporate culture of such companies has a significant and positive influence [30]. Similar to the current study, Heimerl et al. [15] compared the two Alpine regions of North Tyrol and South Tyrol to explore job satisfaction in the tourism industry. The results indicate that South Tyrolean employees were more satisfied with most aspects of their work than North Tyroleans were. There were particularly large differences in respect of the appreciation of guests (a difference of 41.3 percentage points) and employers (54.8%) and in the profession’s reputation among the general public (44.5%). The studies cited show that job satisfaction in the hospitality sector is primarily determined by nonmaterial, sociocultural factors, which can be summarized as follows:

- The work environment: colleagues, teamwork, and a thoughtful and appreciative approach by the business.

- Job content: variety, scope for initiative, and participation in decision-making.

- Personal development: further training and career opportunities.

The following hypotheses can be derived from this:

- Material factors, such as remuneration, stress, and work hours, can have an influence on job satisfaction, but the drivers for increased job satisfaction are sociocultural factors.

Although the regions are very similar in terms of tourism structures and material factors, their sociocultural factors may vary.

3. Material and Methods

The present investigation employed a questionnaire survey method. In 2018 and 2019, 225 specialists (graduates) were surveyed in South Tyrol along with 91 pupils (apprentices) in North Tyrol who were in their final classes in the Tyrolean Vocational School for Tourism and Commerce, Landeck. In the present study, the differences between the two regions, North Tyrol and South Tyrol, will be compared. Study participants were recruited not on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria but rather with the aim of accessing a cross-section of the cohort that was as broad as possible. The key aim was to represent the whole of the cohort, which comprises 93 pupils in North Tyrol and 451 graduates in South Tyrol. In North Tyrol, 91 pupil interviews were conducted since the survey was undertaken during school hours. In South Tyrol, 44.3% of graduates were interviewed because contact details for the cohort were five years old and over half were out of date. Only a small percentage (4.5%) of those contacted refused to take part in the survey. In the questionnaire, the participants were asked to name aspects of the hospitality industry that they considered particularly positive or negative. The participants were presented with four-point Likert scales and asked to indicate the extent to which their choice of training had been driven by a desire to work in the hotel and restaurant industry as well as how satisfied they felt with their training. Decision questions (yes/no) were presented to determine whether the participants would, given their time again, make the same decision to train in the hospitality industry and whether they intended to continue working in the sector. The characteristics of the collected data were then subjected to Chi-square testing to identify the significant, influential factors.

4. Results

4.1. Perceived Advantages and Disadvantages of Working in the Hospitality Industry

Contact with the general public was emphasized as a particular advantage of working in the hospitality industry. Furthermore, international job opportunities (especially in North Tyrol) and the content and type of work (especially in South Tyrol) were highly appreciated. Income and opportunities for personal development were also identified as advantageous. Appreciation by one’s employer and the image of the tourism professions among the general public were not widely cited as advantages. (see Table 3)

Table 3.

“Which aspects of working in the hospitality industry are the greatest benefits for you personally?” Percentage of respondents.

International job opportunities were cited as significantly more advantageous in North Tyrol (Table 4). Few North Tyrol respondents named appreciation from guests as an advantage of the profession, though significantly more South Tyrol respondents did so (Table 4).

Table 4.

Chi-squared test: advantages in the hospitality industry—comparison of South Tyrol and North Tyrol.

All respondents perceived their working hours to be the greatest disadvantage of their job. Approximately a third of the South Tyrol graduates mentioned the incompatibility of their family and professional lives as the second most substantial disadvantage. For the North Tyroleans, the second-largest disadvantage was the negative perceptions of their employer. Stress was cited as equally disadvantageous in both regions. The North Tyroleans ranked income as the third most substantial drawback. (see Table 5)

Table 5.

“Which aspects of working in the hospitality industry do you personally find to be the most disadvantageous?” Percentage of respondents.

In comparison, the South Tyrolean interviewees saw the incompatibility of family and professional life as significantly more disadvantageous. This may be because the South Tyrolean graduates had already been in work for five years and had therefore reached a different life stage. In North Tyrol, on the other hand, working hours were perceived as significantly more disadvantageous than in South Tyrol. Moreover, North Tyroleans were significantly more critical of the (lack of) appreciation they received from their employers as well as their income and workplace climate. (see Table 6)

Table 6.

Chi-squared test: disadvantages in the hospitality industry—comparison of South Tyrol and North Tyrol.

There were mixed views of income. While approximately 25% of the respondents cited income as an advantage of the job, a small number of South Tyroleans (7%) and a larger number of North Tyroleans (19%) said it was disadvantageous. This difference is assumed to be the result of differences between the survey cohorts, specifically, the fact that one group was made up of employees and the other of apprentices (see Section 3).

The perceived advantages of working in the hospitality sector confirm the positive influence on job satisfaction of the sociocultural factors referred to in paragraph 2 (see research question 1): contact with other people is seen as a particular advantage. Job content and development opportunities are also seen as positive elements. The two regions studied have clear differences with regard to the perception of international job opportunities and job content as advantages. In each region, around one-quarter of respondents also cited earnings as an advantage, showing that remuneration is considered to be fair in many places. Work hours are perceived as the predominant disadvantage in both regions. The structure of working hours results from the nature of the hospitality industry, which sees major fluctuations in capacity on a daily, weekly, and seasonal basis. However, these can be mitigated by management decisions (see Section 5).

4.2. Intention to Work in the Hospitality Industry

The factors of respect, relationships, and a friendly environment were found to have a significant impact on overall job satisfaction [10]. Employee expectations of the company and the job in relation to working conditions, pay, safety, leadership of employees, and so on are described by Kong et al. [21] as organizational influencing factors and key drivers of job satisfaction. Of the South Tyrolean graduates surveyed in the present study, 73.5% continued to work in the hospitality industry five years after graduation. Of the cooks, 85.4% were still working in the restaurant industry and, for the restaurant specialists, the figure was 91.7% [31]. The reasons given for this were the working conditions, a desire for training, other job opportunities, and personal factors. In contrast, just 48.3% of the prospective graduates of the Landeck regional vocational school said they intended to continue working in the hotel and restaurant industry after completing their apprenticeship, compared with 58.8% of the skilled workers and 40.4% of the hotel assistants. These figures are in line with the assessments of entrepreneurs of apprentices in the hotel and catering sector, with an average of 45% of entrepreneurs rating the skills and performance of apprentices as “poor” [1]. This clearly reveals a “relationship problem” between entrepreneurs and apprentices.

Thus, whereas, in South Tyrol, three-quarters were still in the career they trained for after 5 years, in North Tyrol, only half of the graduates wanted to enter the career they had trained for (see research question 2). North Tyrol has two vocational-technical schools with a total of 152 graduates. Each year, therefore, only around 75 trained individuals want to enter the career they have trained for. This exacerbates the medium-term decline in graduates from 240 (2010) to 152 (2018). At the same time, employment in tourism services in North Tyrol rose between 2010 and 2017 by around 22.7% [32]. This illustrates the striking shortage of skilled workers and the great practical importance of attractive careers being on offer in the sector.

4.3. Satisfaction with Choice of Training

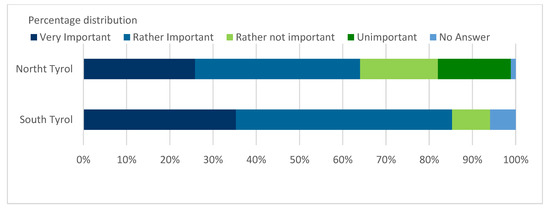

The third research question concerned the respondents’ satisfaction with their choice of training. A desire to work in the hospitality industry was generally a more important driver for graduates in South Tyrol: more than 85% of South Tyroleans stated that working in the hotel and restaurant industry was a decisive influence on their choice of training, while just 64.0% of North Tyrolean apprentices shared this view (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

“When choosing your training, how important was a desire to work in the hospitality industry?”.

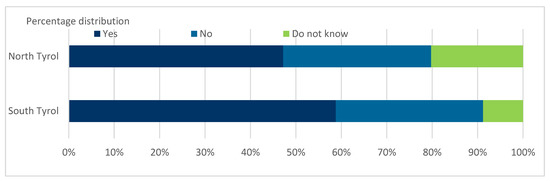

Nearly 60% of South Tyroleans who had completed an apprenticeship said they would make the same choice again, whereas less than half of the North Tyrol apprentices (47.2%) said this (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“If you could choose again, would you still choose to train in the hospitality industry?”.

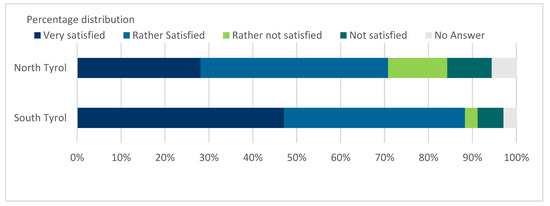

A similar picture emerges in satisfaction with training. In North Tyrol, just over 70% of the graduates said they were satisfied with their training, while, in South Tyrol, the figure was almost 90% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

“How satisfied are you overall with your training?”.

There were also significant differences in terms of satisfaction with training. For the South Tyrolean apprentices, career choice was more influential in their training decisions. The respondents were more likely to say that they would opt for this training again, and they were much more satisfied with the training than their North Tyrolean colleagues.

Although graduates were largely happy with their training (see research question 3), only around half of them would choose vocational training again. This shows that trainees begin their training with expectations that the careers in question do not fulfill. Their initially high level of motivation to work in the tourism sector declines significantly during or after training.

5. Discussion

This paper has identified various influences on the three outcome measures of job satisfaction, intention to work in the sector, and satisfaction with training. Further, the study sheds light on the relationship and interaction between job satisfaction and sustainable development issues.

Overall, this paper showed that job satisfaction and satisfaction with tourism-sector training are significantly higher in South Tyrol than in North Tyrol despite the similarities in the two regions’ tourism structures. However, there is significantly greater variation in the intensity of tourism in North Tyrol.

In terms of job satisfaction, social sustainability can be measured by, among other things, the KPI employee turnover rate [28] or the KPI satisfaction rate [11]. While the former is potentially easier to measure and observe, the latter indicates potential problems earlier, even before employee turnover occurs. The KPI job satisfaction ratio can be measured by a questionnaire [11]. For the questionnaire, it is important to determine important and relevant items for job satisfaction. This study gives a valuable insight in this respect (see Table 3 and Table 5). The implementation of KPIs and the regular measurement would make the enterprises in North Tyrol aware of existing problems at an early stage, especially with regard to the appreciation issue (Table 6). This can then be addressed, measures can be taken, and sustainable development promoted. Thus, the increasing unwillingness to continue working in the tourism sector in North Tyrol could be reduced at an early stage. Training hours per employee also serve as a KPI [28]. However, the present study shows that there is another important factor in this respect, namely, satisfaction with training. Hence, another possible KPI would be the training satisfaction rate. This would be particularly advantageous because, firstly, it would allow intervention at a very early stage of the career and, secondly, the measurement could be carried out simply by means of questionnaires or staff interviews. A focus on training satisfaction would not only have the potential to reduce the employee turnover rate but also to keep young talents in the tourism sector long term.

The concept of “sustainable leadership” and its holistic approach to organizational sustainability [7,22,23] focuses on the needs of the employees and could solve the problems revealed in the results, especially the socially related issues such as workplace climate or the appreciation by guests and the employer. Since “sustainable leadership” aims to balance the needs of employees, economic growth, and the environment [7,22,23], it has the potential to influence sustainability in a variety of ways. The results show that in North Tyrol, a large part of the population does not want to work in the tourism sector in the long term. This can be avoided through “sustainable leadership” by increasing job satisfaction, leading to a more sustainable labor market. The results also show that the respondents in North Tyrol were more dissatisfied with the training. Even at this very early stage, “sustainable leadership” can lead to higher (training and job) satisfaction, more sustainable training, and long-term careers for young talents in the tourism sector. “Sustainable leadership” also includes environmental sustainability issues. Environmentally conscious management might subsequently be transferred to employees due to spillover effects, as lived values and actions could be adopted by employees and integrated into their own lives, attitudes, and actions. This would be of particular importance in nature-based regions [25].

Thus, job satisfaction has the potential to influence a variety of sustainable development issues in the areas of sociocultural and economic as well as environmental sustainability.

The social contact associated with the tourism professions, the content of the work, and the opportunities for further development (e.g., international perspectives and further training) were all identified as positive factors for job satisfaction. These factors are motivators [33], and any associated costs are purely indirect. An emphasis on developing these areas could, therefore, increase the intention to pursue the profession and reduce employee turnover.

The disadvantages described above present a picture of North Tyrolean apprentices as suffering a lack of recognition for their work [15]. As the second most frequently cited disadvantage (after working hours), a lack of appreciation by one’s employer was perceived by almost a quarter of respondents to be a problem. In addition, the skilled workers named work-related stress and the incompatibility of their family and professional lives as key inhibiting factors. These findings provide a starting point for increasing job satisfaction in the hospitality industry, and they are dealt with in more detail in the following sections.

5.1. Working Hours and Stress

By a substantial margin, the South Tyrolean (78%) and North Tyrolean (92%) respondents cited working hours as the greatest disadvantage of working in the catering professions. It is imperative that working hours are adapted to the needs of young people. Flexible working time models and regulated working hours that guarantee planning security and support greater compatibility between family and career are essential. Trainees in the hospitality industry must have weekends away from work or at least be guaranteed a maximum five-day working week. Family-unfriendly working hours and work-related stress are inevitable in this sector due to fluctuating seasonal and intraday workloads; thus, to compensate, sociocultural stressors must be taken into account. This includes leadership at all hierarchical levels, appreciation by the employer, the working atmosphere, and so on. This highlights once again the importance of the dimensions of esteem, as noted earlier. Significant differences between the two regions were observed in the dimension of appreciation [15], and there is great potential for improvement here, especially in North Tyrol. Large differences are also evident in terms of training satisfaction and intention to remain in the profession. There is, therefore, a need to improve in the following areas below, particularly in North Tyrol.

5.2. Personnel Management

In terms of appreciation, the above-mentioned results align with those of a 2019 survey of 96 hoteliers in North Tyrol [34]. Of the respondents in that study, only 60% saw leadership as very important or important. This indicates that conscious and possibly appreciative personnel management is considered only partially important or completely unimportant by 40% of entrepreneurs. Simply put, a responsible and appreciative management attitude is either handed down by the corporate culture, or it is not. From this follows the question of one’s socialization as a manager in the hospitality industry. The East Alpine tourism structure is characterized by family businesses, with essential cultural characteristics of being “hands-on” and “closed shops” [35]. An evidence-based culture does not prevail in Alpine tourism. In many cases, entrepreneurial socialization happens from childhood onwards and is often not supplemented, reflected, or enriched by experiences of different corporate cultures or university education. Today, this traditional management culture is confronted by the values of Generations Y and Z, who demand autonomy, appreciation, a work–life balance, and development potential [36]. If an industry cannot meet these demands, other sectors become more attractive. These hypotheses should be examined in future research in connection with leadership awareness and principles, with management and employee surveys used to gather data.

5.3. Appreciative Corporate Culture Towards Guests and Employees

An appreciative corporate culture is regarded as a bond between employees and guests: satisfied employees make satisfied guests, regular staff makes regular guests, and an appreciative corporate culture is reciprocated by the guest in an appreciative manner. Apprentices naturally begin their careers at the lower hierarchical levels of a company. Those who are met there with esteem become confident that they will consistently be treated well. With approximately half of the North Tyrolean final-year students (compared to 26% in South Tyrol) saying that they did not intend to work in the profession in the future, it is clear that formative negative experiences during the apprenticeship period have an impact. These suppositions should be pursued through qualitative research.

5.4. The Image among the General Public

The image of the profession among the public, especially the relatives and peers of the young people, was important for both groups in the study. It would be valuable to investigate whether the profession’s public image reflects the sector’s problems with its management and corporate culture, or whether a general attitude towards tourism influences its professional image. Connections between the intensity of tourism and its public image should also be examined. Despite the two study regions’ very similar overall tourism intensities (see Table 1), there were marked differences in their respective professional images. However, an examination of the variances in tourism intensity in the 50 most tourism-intensive municipalities reveals significant differences between various parts of the country. This supports the hypothesis that public attitudes to tourism suffer in destinations of both particularly low and particularly high tourism intensity. In contrast, a medium and homogeneous intensity tends to be conducive to positive attitudes to tourism. This correlation can be explained by the following hypotheses. A large proportion of the population in areas with very low levels of tourism perceives tourism as being of little or no relevance. The sector is therefore not considered important and is held in low esteem. This is different in areas with high levels of tourism. Here, tourism is dominant, and residents feel their interests are neglected in favor of guests’ interests and that their quality of life is adversely affected. This results in resentment and disrespect. This inverse U-shaped relationship between tourism intensity and public image would provide a further starting point for valuable future research (see Table 2).

The results and the discussion have some practical implications that support the two aims referred to at the start (reducing fluctuations and securing new talent for skilled jobs):

- The lever for increased job satisfaction is clearly sociocultural factors, such as work environment, social contact, job content, and opportunities for personal development. The main focus of responsibility for these factors lies with businesses and management.

- Remuneration is perceived differently in the two regions studied but is viewed as an advantage in many places. Material factors need to be guaranteed but are not what motivates people.

- Work hours are perceived as by far the biggest disadvantage. These are fundamental to the sector and can at best be moderated: larger businesses can introduce shift work and seasonal fluctuations can be reduced at the destination level to provide greater continuity.

- Sociocultural factors have particularly clear implications for apprentices: although they are mostly satisfied with their training, only half (in North Tyrol) want to pursue the career for which they have trained. The shortfall is not due to the content or quality of training but manifestly to the quality of the relationships between apprentice masters and apprentices.

- (Sustainable) management in the sense of balancing the needs of employees, economic performance, and the environment can not only lead to greater job satisfaction through the positive impact on sociocultural factors but can also promote further sustainable developments.

- The implementation of KPIs is particularly important for measuring and strategically embedding social sustainability objectives, such as job satisfaction.

Career expectations clearly do not match the experience of the career or of practical occupational training. This suggests that improved career guidance and opportunities for practical experience are needed before career choices are made.

6. Limitations and Areas of Future Research

The differences in individual satisfaction factors may be explained by the differences between the two groups of respondents in this study (five-year graduates and final-year students). Having left school some years before, the graduates inevitably ranked the compatibility of their family and professional lives more highly than those in their final school year did. It is also notable that the North Tyrol N of 91 was significantly lower than that of South Tyrol (225).

This research has revealed topics in need of further investigation. First, it would be particularly interesting to examine the prevalence, effectiveness, and type of use of KPIs in the tourism sector. Second, future research projects should deal with the relationship between sustainable leadership and job satisfaction and their impact on the behavior and attitudes of employees. In this context, attention should be paid to the adoption of sustainable values and actions by employees. Third, an in-depth study of the factors and events responsible for unwillingness to work or the intention to quit in the tourism sector would be interesting.

The data used here were gathered prior to the COVID-19 crisis. The short- to medium-term research on job satisfaction in hospitality will, of course, focus on strategies for coping with this crisis. Owing to the shift from mass to quality tourism mentioned in the introduction to this paper, job satisfaction is of increasing importance. In a quality strategy, dissatisfaction with material factors (e.g., income, working hours, and place of work) is harmful, while satisfaction with nonmaterial factors (e.g., personnel management, appreciation, and professional image) is ultimately decisive. This finding should be investigated in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H. and M.H.; methodology, P.H.; software, M.H.; formal analysis, U.P.; investigation, M.R. and U.P.; resources, P.H.; data curation, M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.H. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, P.H. and M.H.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, P.H.; project administration, P.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WKO; W.Ö. Ausbildung im Gastgewerbe. Available online: https://www.wko.at/branchen/vbg/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft/gastronomie/Ausbildung_im_Gastgewerbe.html (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Chang, C.; Gruner, A. GVO Study: HR Trends in the Hotel and Catering Industry—Impulses for Future Personnel Management. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/de/document/read/23356229/gvo-studie-hr-trends-in-hotellerie-gastronomie-gvo-personal- (accessed on 19 January 2020).

- Pranoto, E.S. Labour Turnover in the Hospitality Industry. Binus Bus. Rev. 2011, 2, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.C.; Timo, N.; Wang, Y. How much does labour turnover cost? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.W.; Davis, K. Work stress and well-being in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, R.T.; Johnson, K.; Hebert, J.; Ajzen, I.; Copeland, J.; Brown, P.; Chan, F. Understanding employers’ hiring intentions in relation to qualified workers with disabilities: Preliminary findings. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2010, 20, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G.C. Employee satisfaction and sustainable leadership practices in Thai SMEs. J. Glob. Responsib. 2014, 5, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aon, H. The Latest Trends in Global Employee Engagement. Available online: https://www.aon.com/attachments/thought-leadership/Trends_Global_Employee_Engagement_Final.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Strenitzerová, M.; Achimský, K. Employee satisfaction and loyalty as a part of sustainable human resource management in postal sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, R.; Patiar, A.; Herington, C.; Creed, P.; Davidson, M. Development and initial validation of a hospitality employees’ job satisfaction index. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1814–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A. The role of sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) in implementing sustainable strategies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STOL Anzahl der Spitzenhotels in Süd- und Nordtirol Steigt Rasant. Available online: https://www.stol.it/artikel/wirtschaft/anzahl-der-spitzenhotels-in-sued-und-nordtirol-steigt-rasant (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Tirol, L. Tourismus in Tirol. Available online: https://www.tirol.gv.at/statistik-budget/statistik/tourismus (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Südtirol, A. Datenbanken Gemeinden. Available online: https://astat.provinz.bz.it/de/datenbanken-gemeindedatenblatt.asp (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Heimerl, P.; Haid, M.; Perkman, U.; Rabensteiner, M.; Campregher, P.; Lun, G. Job satisfaction in the hospitality industry: Does the valuation make the difference? Anatolia 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einramhof-Florian, H. Die Arbeitszufriedenheit der Generation Y: Lösungsansätze für Erhöhte Mitarbeiterbindung und Gesteigerten Unternehmenserfolg; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Neuberger, O.; Allerbeck, M. Messung und Analyse von Arbeitszufriedenheit (Measurement and Analysis of Job Satisfaction); Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Six, B.; Felfe, J. Einstellungen und Werthaltungen. In Enzyklopädie der Psychologie. Organisationspsychologie 1—Grundlagen und Personalpsychologie; Schuler, H., Ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2004; pp. 597–672. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, T.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. The job satisfaction gender gap among young recent university graduates: Evidence from Catalonia. J. Soc. Econ. 2009, 38, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. What is job satisfaction? Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1969, 4, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Jiang, X.; Chan, W.; Zhou, X. Job satisfaction research in the field of hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2178–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Honeybees & Locusts: The Business Case for Sustainable Leadership; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable Leadership: Honeybees and Locusts Approaches; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros-Kidd, A.M.; Monz, C.; Hausner, V.; Schmidt, J.; Clark, D. Nature-based tourism, resource dependence, and resilience of Arctic communities: Framing complex issues in a changing environment. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, C.; Oshika, T. Disclosure effects, carbon emissions and corporate value. Sustain. Acc. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A. Developing a framework for sustainable development indicators for the mining and minerals industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2004, 12, 639–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabčanová, I. Human resources key performance indicators. J. Compet. 2012, 4, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, P.; Cengiz, G. The Connection between the Motivation Level of the Employees Job Satisfaction and Tendency to quit the Job in Tourism Sector. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2013, 5, 380–392. [Google Scholar]

- Dirisu, J.; Worlu, R.; Osibanjo, A.; Salau, O.; Borishade, T.; Meninwa, S.; Atolagbe, T. An integrated dataset on organisational culture, job satisfaction and performance in the hospitality industry. Data Brief 2018, 19, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siller, M.; Perkmann, U. WIFO Report 3.18: Workplace in the Hospitality Industry. Survey of Graduates of Hospitality Schools in South Tyrol; WIFO Institute for Economic Research of the Bolzano Chamber of Commerce: Bozen, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WKO; W.Ö. Tourismus und Freizeitwirtschaft in Zahlen 2019. Available online: https://www.wko.at/branchen/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft/tourismus-freizeitwirtschaft-in-zahlen-2019.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Herzberg, F. One more time: How do you motivate employees. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1968, 46, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Benedikt, L.; Heimerl, P. Employer Attractiveness in the Hotel Industry in the Landeck District; Division for Management in Health and Sports Tourism of UMIT: Hall in Tirol, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gardini, M.A. Der Mitarbeiter als Erfolgsfaktor? Personalmanagement im Tourismus zwischen Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. In Personalmanagement im Tourismus: Erfolgsfaktoren Erkennen—Wettbewerbsvorteile Sichern; Gardini, M.A., Brysch, A.A., Eds.; Erich Schmidt: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 35–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrelmann, K.; Albrecht, E. Die Heimlichen Revolutionäre: Wie die Generation Y Unsere Welt Verändert; Beltz Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).