1. Introduction

Energy issues in tourism have gained a lot of public and scientific attention as a result of a significant increase in energy prices, as well as concerns over the environment and sustainable development. An increase in energy prices is subject to both time and space as it varies by country and region. These studies are focused on how to improve energy efficiency, how to reduce CO

2 emissions, and how to implement renewable energy sources in tourist facilities without harming economic growth. Every tourist destination wants to carve its place on the market by having a diverse offer while shaping a recognizable tourist product. Destinations aim for these goals as they observe high ecological standards and apply contemporary methods and techniques alongside strong IT support and new technologies, innovations, and knowledge [

1].

Implementing sustainable development plays a key role in market placement. The seventh of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations for 2030 is to achieve affordable and clean energy [

2]. The “Agenda 21 for Tourism and Travel Industry”, developed by the World Travel and Tourism Council in cooperation with the World Tourism Organization, addresses resource management and energy use as one of the major issues [

3]. Tourist facilities becoming sustainable is paramount for reducing the negative impact they have on the environment, as buildings and construction account for more than 35% of global final energy use and nearly 40% of energy-related CO

2 emissions [

4,

5].

Tourism gains numerous benefits by implementing principles of energy management [

6,

7]. Energy efficiency is an issue affecting both the environment and the economy. Most approaches aiming at reducing the energy impact of a site focus only on one specific aspect: appliances, local generation, or energy storage [

8]. Hotels are buildings with the highest energy consumption in the tertiary sector because of how they operate and their large number of users [

9,

10]. As of January 2020, Europe has 300,000 hotel rooms [

11]. Such a large number, as well as the rapid construction of new hotels, points towards the great effect hotels have on the environment. Hotel units are responsible for a significant proportion of energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions in tourism [

12].

Hotels having this significant and negative impact, combined with the need to protect the environment, has led to more and more hotel owners and managers establishing the ISO 50,001 energy management system [

13,

14,

15]. Authors Dall’O et al. confirm the effectiveness of ISO 50,001 as an organizational tool for energy management with a systematic approach [

16]. Energy management plays a significant role in strengthening sustainability and increasing energy efficiency [

17]. Adopting energy management practices can be considered a good indicator of future profitability.

The aim of this paper was thus to explore the informedness of managers in tourism pertaining to energy saving, environmental protection, energy efficiency, climate change, and renewable energy sources. Managers from across Adriatic Croatia filled out the questionnaire. Due to the sea, coast, and more developed tourism infrastructure, this part of Croatia achieves better financial results than Continental Croatia and shows more tourist arrivals and overnight stays in all months of the year [

18]. The research question has thus arisen of whether, due to a higher degree of tourism development, the people who manage tourist facilities and make decisions are sufficiently informed about matters of energy. A questionnaire was designed to assess the informedness and perceptions of managers in tourism on these matters. Although the tourist industry is a high energy consumer, very little work has been published on energy saving and renewable energy sources in terms of Croatian managers’ attitudes on the topic. This paper aims to contribute to this gap. Although this paper contributes to the current research on energy efficiency in the tourist industry, its main contribution lies in highlighting the degree to which managers in tourism are aware of the benefits of implementing an energy management system in tourism facilities. If managers are sufficiently informed on energy issues and if they adopt measures concerning energy efficiency and renewable energy sources, their energy-related expenses will consequently be lower. Research assessing the perception of managers in tourism in Adriatic Croatia has thus far been limited regarding this point of view. Some previous Croatian studies focused only on hotel managers [

19], emphasizing the application of renewable energy sources and energy efficiency as requirements for developing sustainable tourism [

20]. The novelty of this study is that it takes such a comprehensive approach to the subject matter as previous literature has only done minimally or not at all. The research laid out in this paper has practical significance as it recommends new approaches to challenges in the tourism industry, suggesting that managers in tourism need to raise their understanding of the importance of energy issues. The study proposes that managers should implement more pro-energy actions. The authors propose concrete steps that each manager in tourism should take in order to make their business more energy efficient. One concern that the paper raises is that managers in tourism are poorly informed about the fact that energy efficiency represents both the future and a necessity in business. Concrete measures regarding energy efficiency are poorly implemented into businesses at present. This research provides reliable and practical qualitative and quantitative data about energy issues in the regions of Adriatic Croatia.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: the following chapter explains the concept of energy management in tourism and provides an overview of relevant literature. The authors then present the methodology used for collecting and analyzing data followed by the empirical results. At the end of the paper, the authors provide concluding remarks, as well as the limitations of this study and recommendations for further research.

2. Literature Review

Energy management offers many advantages such as monitoring energy consumption and reducing expenses, reducing harmful environmental impact, and improving a company’s reputation [

21]. In order to increase the energy performance of the tourism sector, the European Commission introduced the so-called European Ecolabel [

22,

23]. This environmental initiative focuses on encouraging product and/or service development with lower harmful effects on the environment. In the tourism sector, the European Ecolabel represents not only an instrument for improving the quality of the environment but also for reducing management costs, and it represents a valuable marketing tool for improving a hotel’s image. The Ecolabel criteria specifically aim to limit energy and water consumption to promote the use of renewable energy sources and to promote education and communication about the environment [

24]. For some managers, the Ecolabel represents a motivation for thinking about reducing energy consumption. It is not just hotels, however. Other tourist facilities are also implementing various measures and activities concerning environmental protection [

25].

Larger hotels, especially big international hotel chains, implement more measures and take a more active approach toward environmental protection compared to smaller hotels, hostels, tourist settlements, camps, and other types of accommodation. Regardless, it is important to point out that every manager should contribute to environmental protection and increasing energy efficiency within the limits of their domain [

26].

The basic premise in sustainable business is to implement principles of energy efficiency and then increase it to achieve positive effects. It is imperative that tourism facilities have efficient heating, cooling, and lighting systems and the ability to regulate how they operate. According to Maksin et al., it is vital to ensure energy management and establish an intelligent system for energy monitoring, particularly in larger tourist complexes [

27]. Big companies have a greater negative effect on the environment as they consume more resources, thus generating more waste and harmful gas emissions. A typical hotel has a yearly emission of 160–200 kg of CO

2 per square meter of a hotel room, generates 1 kg of waste per guest per day, while European hotels annually spend 39 TWh of energy, half of which amounts to electrical energy [

28].

Alvarez et al. state that the hotel industry’s effect on the environment is evident but also that it is easier to control large hotel chains as they are centralized sources of pollution that have developed broader practices for managing sustainable development compared to smaller hotels. They can also be role models for smaller tourist companies which justifies the pressure faced by big hotel companies [

25]. This pressure increases as the hotel company increases, and the environmental performance of hotel companies proportionately decreases as the hotel decreases in size [

29].

Hotel chain management thus has to constantly develop contemporary systems and efficiently manage energy for the sake of environmental protection. On the other hand, hotel chains have significant advantages such as greater funding for investments, formal management, and using the economy of scale which in practice enables them to implement a practical system for energy management. Larger hotels will more easily become ecologically responsible than smaller hotels, primarily because of their ability to achieve more challenging financial investments, which can be one of the reasons whether or not the hotel becomes sustainable [

30]. Every tourism facility manager has their own development policy that should include implementing the principles of sustainable development. Managers working in larger systems have to follow company guidelines regarding how to develop and efficiently implement activities and measures, which can prove more difficult for a manager in a smaller or individual facility. Tourism facilities in a larger group have the option of testing specific innovations in particular hotels and their divisions and then applying them to other facilities if proven successful.

Dogra et al. consequently claim that investments also lead to greater employment rates [

31]. Tourist chains also set common, minimal norms and standards to be observed in all facilities in order for the “green” strategy to be unified for all facilities in the corporation [

32]. Modica et al. explored the impact of economic, social, and environmental sustainability practices concerning companies in the hospitality supply chain on consumer satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness to pay more. They collected data from 288 tourists in South Sardinia and their study showed that economic sustainability practices have a positive impact on consumer satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness to pay premium prices. The study, however, also showed that environmental and social sustainability practices have a direct positive impact on consumer satisfaction and an indirect positive impact on loyalty and willingness to pay premium prices [

33]. Even though energy management has many advantages and it is exceptionally important for efficiently running hotels, Parisi stated that many hotel owners and investors remain skeptical [

34]. This pertains to hotel managers having poor awareness concerning new energy technologies. Additionally, hotel managers having poor knowledge concerning IT caused them to hesitate when it comes to adopting new technologies in their operations [

35,

36,

37]. They were concerned that new technologies would affect their role of providing personalized services to hotel guests, and they hesitated when it came to the possible applications of those technologies. Nazari et al. found that customer satisfaction concerning hotel technology services can enhance a hotel’s business advantage [

38]. Nyuur et al. interpreted manager perceptions when it comes to activities concerning sustainability among diverse stakeholders in Croatia. The analysis showed that corporate sustainability is an emerging concept. It also showed that activities concerning sustainability are primarily focused on environmental protection, investing in community partnerships, and enhancing companies. However, managers did perceive sustainable initiatives as necessary for business in the context of research [

39]. In order to examine the issues of sustainable development, climate change, and environmental protection, the Institute of Management and Technology conducted a one-year-long piece of research involving in-depth interviews with fifty global leaders and a questionnaire filled out by over 1500 participants worldwide. When it came to the main reasons for solving the matter of sustainability, the participants found how it affected the brand and image of the business to be the most important factor [

40].

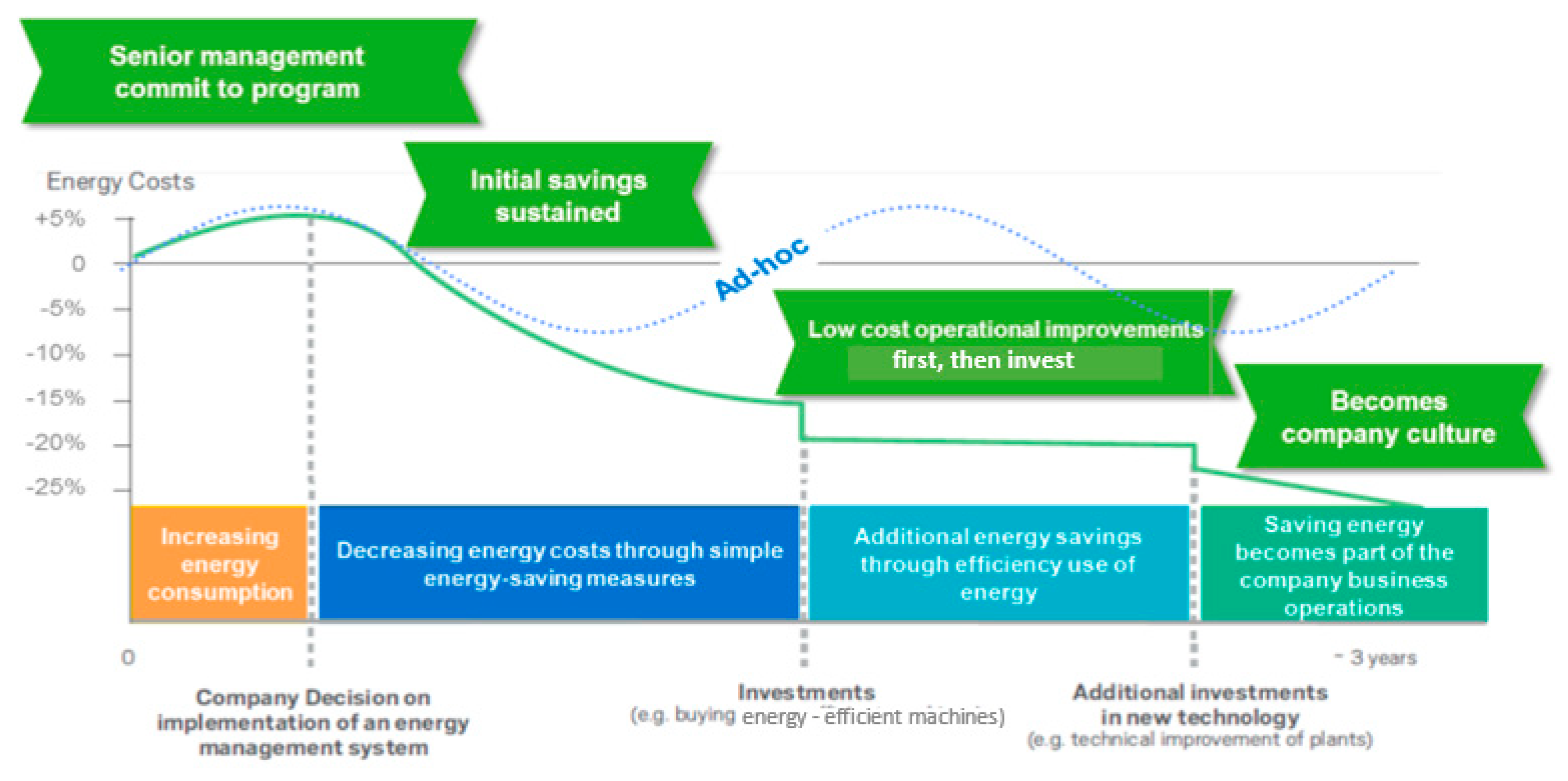

Figure 1 shows the process that companies, i.e., managers use to reach the decision to undertake energy management.

Figure 1 shows the initial high expenses regarding energy due to increasing energy consumption. Even the simplest measure can result in a reduction in energy expenses. Companies, therefore, do not have to immediately make a decision regarding large-scale investments. They should work on simple measures for saving money instead. However, implementing energy efficiency measures and additional investments in new technologies results in a reduction of energy-related expenses, and measures to save energy become a standard part of a company’s business culture.

Williams and Schaefer analyzed managers in Eastern England and found that they had a relatively good understanding of environmental issues and climate change and that their companies had already adopted various pro-environmental measures [

42]. According to this study, personal values and beliefs are the most significant motivation for managers in tourism to tackle environmental issues and issues of climate change. Managers who take on environmental issues have displayed an internal locus of control. Some of these findings contrast the views stated by key stakeholders in local government and consulting organizations who tend to emphasize arguments concerning expenses when encouraging small businesses to adopt greater environmental engagement. Manan et al. indicate that top managers in Malaysia lack awareness concerning environmental and energy issues. In cases when top management is dedicated to implementing environmental education activities, the lack of experience in the field nevertheless remains detrimental for project implementation. Furthermore, when running environmental education projects, some results are unpredictable, which makes companies reluctant to use their own resources to implement them [

43]. Another study was conducted in Macedonia where the authors explored the attitudes of hotel managers. The results indicated that they had high positive attitudes concerning environmental protection issues and that they were highly aware of the benefits brought by the energy-sustainable concept, which in turn supports the European environmental impact assessment regulation [

44]. It is evident that there is a large number of papers tackling this subject, but an insignificant number covers managers in Croatia.

As an introduction to this research, we list studies that took place in the Croatian coastal subregion known as Kvarner, where the first phase was conducted in 2004, the second phase in 2007, and the third phase in 2012 [

45,

46,

47]. The authors of these studies explored the attitudes of tourists, residents, and managers. The results throughout all three phases showed that all categories of respondents considered natural factors to be major contributors to tourism. According to all three groups, the most valued assets were landscape, climate, environmental preservation, and the clean sea. These results indicate that all three groups agreed that the natural factors—space, resources, and the environment—have to be protected [

48]. As a sort of continuation to these three phases, this paper expands the covered area to all seven counties across Adriatic Croatia and looks into energy issues. The target group of this study was managers in tourism.

3. Research Methodology

This chapter provides the research methodology used in the study with descriptions of the study area and the questionnaire, as well as data analysis.

The research was conducted in order to collect current, reliable, quantitative, and qualitative data regarding how informed managers in tourism are when it comes to energy issues. The questionnaire included questions to see how well-informed the respondents were regarding energy saving, use of renewable energy sources in tourism, alternative fuels, plans for developing new energy-related projects in tourism, measures for more efficient use of energy and renewable energy sources being implemented at the national level, and informedness regarding climate change. The aim was to conduct empirical research of how well-informed managers in tourism are by analyzing:

The managers’ socio-demographic profiles,

How well-informed the managers are regarding energy issues.

These questions may seem simple, but they are nonetheless very important for business in tourism. People in charge of maintenance in hotels are typically the ones making decisions concerning matters of energy. A hotel’s technical staff does not include a manager position, i.e., a person who knows engineering, electrical engineering, other technical branches, as well as economic doctrines regarding maintenance. It should not be expected of managers to be experts in all sectors, but they need to know how the system works, particularly when it comes to implementing a renewable energy source. Managers’ informedness is in this case paramount for decision making. The question then arises whether a hotel’s head of maintenance can influence cost reduction and the rationalization of expenses and whether managers can leave the decision to make an investment to the head of maintenance. Of course, thinking about adopting measures concerning energy efficiency can only be done through the collaboration between all departments, but if the manager is not sufficiently informed on energy issues, then it becomes more difficult to make decisions. There are various occupations covering this area such as Energy Advisor, Director of Environmental Sustainability, various advisors in the field, or heads of energy departments. Conversations with managers have, however, shown that they are the ones who have to tackle all of these issues so their informedness is paramount for focusing on energy-related expenses.

3.1. Study Area

The Republic of Croatia is included in the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) of the European Union. The NUTS levels were defined during the Accession of Croatia to the European Union, codified by the Croatian Bureau of Statistics in early 2007. The regions were last revised in 2012. The three NUTS levels are:

This paper covers the counties of Adriatic Croatia, as seen in

Figure 2. These include Istria County, Primorje-Gorski Kotar County, Lika-Senj County, Zadar County, Šibenik-Knin County, Split-Dalmatia County, and Dubrovnik-Neretva County.

As stated in the introduction, the region of Adriatic Croatia was selected for the study due to the sea, coast, and more developed tourism infrastructure that achieves better financial results in tourism and records higher tourist arrivals and overnight stay than Continental Croatia in all 12 months of the year [

50]. It is therefore interesting to examine if managers in these areas display a higher degree of informedness and ”greener” attitudes concerning matters of energy. The questionnaire was distributed online using unique criteria and with the assistance of the city, municipality, and tourist-settlement tourist boards. The questionnaire was ultimately filled out by 254 managers in such a way that encompasses business management, tourist board management, management in units of local self-government as well as managers among other stakeholders directly or indirectly involved in creating the tourism product of this destination, as shown in

Table 1.

Eighty percent of activities in tourism in Croatia take place in Adriatic Croatia. Furthermore, managers from all 7 counties were included, mostly from Primorje-Gorski Kotar (26%) and Istria (23%). The sample was also well-balanced, as the respondents hailed from all management structures: hotel, villa, camp, and apartment managers (47%), managers in tourist boards (30%), and to a slightly smaller degree, managers from units of local self-government (23%).

3.2. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was tested on a small sample of 15 preliminary respondents to ensure the clarity of the questions asked, the coherence in line with the purpose of the questionnaires, and the time required to answer all questions. The final version was produced after making corrections to a few questions on the basis of initial suggestions.

Empirical research was conducted between 1 December 2019 and 15 February 2020 in order to avoid polling during the seasonal summer months. This was done due to the fact that summer months typically mean a larger degree of work for managers resulting in reduced interest in filling out questionnaires. Data was primarily collected online by sending the questionnaire via email, while some managers were interviewed in person in the field or by phone. A research team performed the fieldwork and polling. The questionnaire included closed-ended questions, answered using the Likert scale with 1 being the worst and 5 the best.

The questionnaire was developed based on similar studies [

45,

46,

47] while following the examples laid out by other researchers as described in the previous chapter. The questionnaire was designed specifically for this study, taking into consideration that respondents can provide only one answer to each question.

The filled-out questionnaires were encoded and all data was loaded into STATA 13.0, StataCorp2013. The data was processed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 13, followed by grouping and analyzing the obtained output.

4. Results and Discussion

The results point toward the profiles of the respondents, i.e., 254 managers in tourism who were directly involved in managing energy in their facilities or on the level of their tourist destinations.

Table 2 shows the demographic features—gender, age, and education level—of the respondents.

The questionnaire was filled out by more people of the female gender (53%), but the difference was small enough to call the gender distribution balanced. Most (80%) of the respondents were aged 40–60, which reflects reality as that is the age of the active workforce, and it can also be an indicator of experience at managerial functions. When looking at education levels, it can be rated as satisfactory since 83% of the respondents had a college or university degree, and 8% even higher. This data is significant as it indicates that energy management is in the hands of well-educated people of an appropriate age whose perceptions can be considered competent.

Seven questions were developed for the purpose of assessing informedness. The validity of the questionnaire was verified using factor analysis and internal consistency analysis (Cronbach’s alpha). Factor analysis has determined one stable factor with an eigenvalue of 2.92400 and Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8251, thus proving the validity of the questionnaire as a tool to measure informedness, as shown in

Table 3.

All responses indicate a positive correlation, and an informedness scale was developed with values from 1 to 5 using the arithmetic mean value of the responses.

On a scale from 1 to 5, the average informedness score is 2.855449 with a standard deviation of 0.7437769. Analysis by gender shows that male respondents had a slightly higher degree of informedness (2.905569 ± 0.7569022) compared to female respondents (2.81164 ± 0.7321127), but the difference is not statistically significant (p = 0.3173).

Looking at

Table 4, analysis of variance shows differences in informedness based on age (

p = 0.0291), while a post-hoc analysis indicates a weak significance between the middle age group and the highest age group. Descriptively speaking, the oldest respondents were simultaneously the most informed, which can partially be attributed to their education and experience in managerial positions.

In

Table 5 authors calculated informedness of managers in tourism on matters of energy—analysis by education level.

ANOVA analysis of this data did not show any statistically significant differences based on respondents’ education level (p = 0.0931).

If the questions are taken as measures of informedness with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8251, then the results are that only 6.7% of the respondents considered themselves to be well-informed (marked 4 and 5) on matters of saving energy, 26.9% consider themselves to be averagely informed (marked 3 and 4), and 66.4% considered their informedness to be poor or negligible (marked 1 and 2).

Table 6 provides an analysis of responses to particular questions.

Looking at

Table 6, it can be concluded that 30.43% of the respondents marked 4 or 5, indicating that they were well-informed or exceptionally well-informed on matters of saving energy and more efficient energy consumption in tourism, while 69.57% considered themselves to be poorly or negligibly informed on the same topic. Such a large proportion indicates that policymakers in tourism should pay more attention to promoting more efficient energy consumption. Additionally, on the subject of renewable energy sources in tourism, 62.46% of the respondents stated that they were poorly informed, and only 37.54% that they were exceptionally well-informed.

The analysis also shows that 33.59% of the managers were well-informed regarding alternative fuels for vehicles such as biodiesel, ethanol, or hydrogen, while 66.41% considered themselves to be poorly informed, meaning that education and promotion of alternative fuels is necessary in order to make tourist destinations cleaner and more eco-friendly. A worrying fact is that only 13.43% of the respondents were well-informed about new energy-related projects in tourism, while 86.57% marked a lower score, which can be yet another indicator of poor informedness. Similar numbers can be seen when it comes to awareness of measures for more efficient energy consumption at the national level. Out of the respondents, 86.17% marked themselves as poorly or averagely informed regarding the measures adopted by the government, which goes to show that the measures themselves are poorly promoted, but also that the managers lack interest in such matters. Measures are implemented by the Environmental Protection and Energy Efficiency Fund, there are several actions taking place, but managers are not aware of them. The reasons for this can be that the measures themselves are poorly promoted, but also that managers are passive when it comes to implementing new actions for energy into their businesses. Only 22.13% thought that they were well-informed about the use of renewable energy sources at the national level, while the remaining 77.87% believed to be inadequately informed. Managers showed an unsatisfactory level of informedness on all questions asked so far. When climate change was concerned, 52.96% of the managers stated that they were well-informed about the issue, representing just over half of all respondents, so it can be concluded that managers follow recent developments at the global level instead of the national level, as climate change has become a very contemporary topic in various social circles.

The characteristics of the respondents, i.e., managers in tourism, as presented in the previous table, are significant for further analyzing their attitudes on future matters and plans concerning energy. Managers in tourism are asked to assess plans concerning energy as realistically as possible, as well as assess tourist needs and desires as realistically as possible, thus making the analysis of their level of informedness particularly important. All of this should be used as a guideline to check how to transform the recognized flaws into advantages and how to ensure proper conditions to do it. The results should also be observed in the context of contemporary knowledge on how developing a relevant foundation of information based on contemporary instruments can help destination management break new ground regarding energy management.

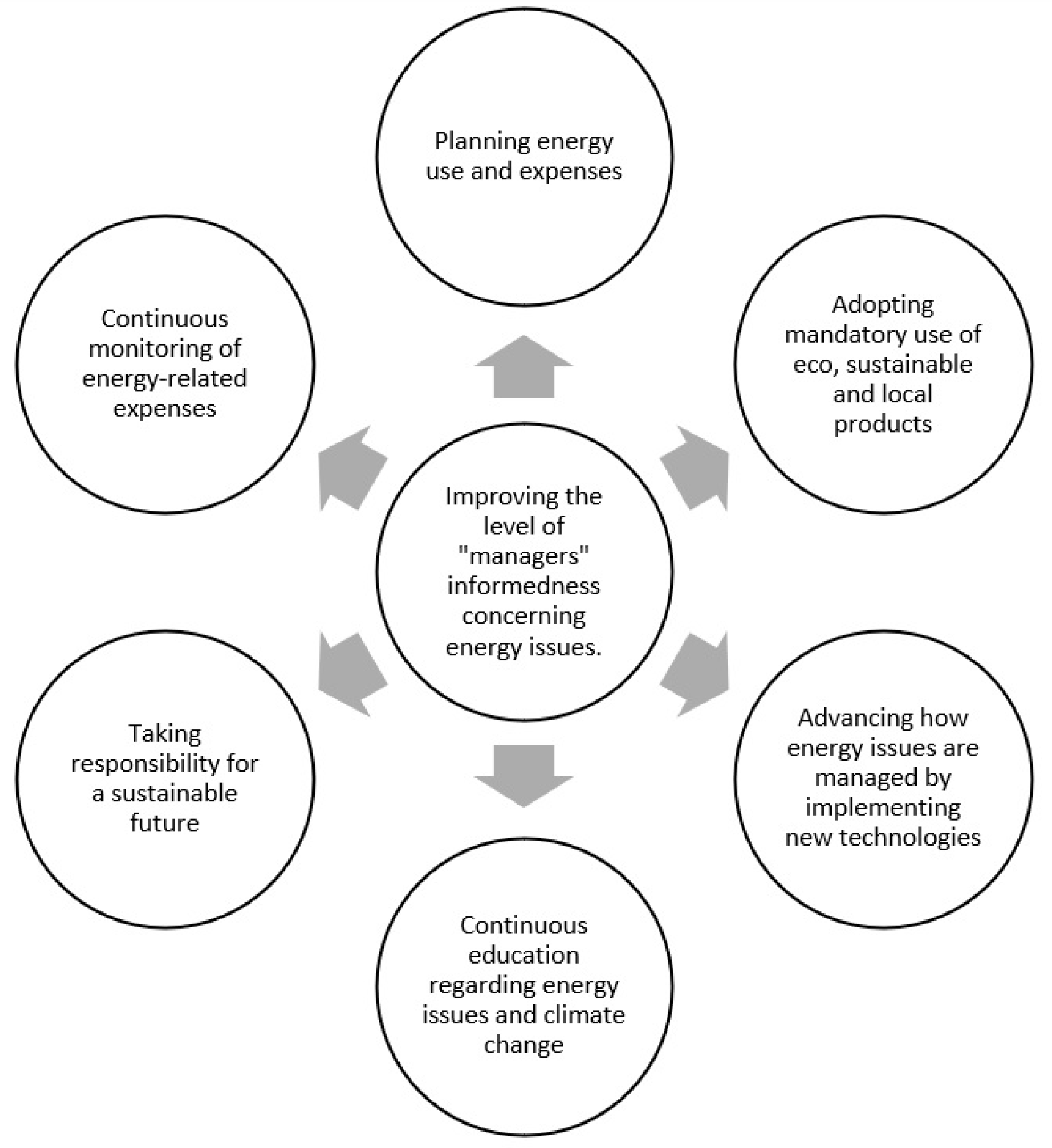

By exploring the available literature and through interviews conducted with managers, we realized that it was necessary to implement specific procedures, i.e., steps for better energy management and reducing energy-related expenses.

For the purpose of improving the level of managers’ informedness concerning energy issues, the authors propose taking concrete steps within their purview (e.g., hotel, camp, tourist board, or destination), as shown in

Figure 3.

Planning energy use and expenses;

Adopting mandatory use of eco, sustainable, and local products;

Advancing how energy issues are managed by implementing new technologies;

Continuous education regarding energy issues and climate change;

Taking responsibility for a sustainable future;

Continuous monitoring of energy-related expenses.

While talking to managers in tourism, we discovered that very few objects in Croatia have adopted a systematic energy management policy, thus implementing measures for energy efficiency for the purpose of green tourism boils down to individual attempts. These attempts need to be transformed into measures that will be implemented on a broader local, regional, and national level. It is, therefore, necessary to plan energy-related expenses and to have a person responsible for monitoring energy expenditure on a daily basis. In order for a tourist object to be sustainable, it has to use local and eco products as that both supports the local economy and creates a better image for the object. Becoming energy-efficient and implementing renewable energy sources is unimaginable without new technologies. Constant and continuous education on energy issues and climate change is a prerequisite for managers being better informed and thus more successfully making decisions with the aim of taking responsibility for a sustainable future. The final but not the least important step is to control and monitor energy-related expenses in order to promptly react to any changes happening in the object.

5. Conclusions

This research provides a small empirical contribution to the development of Adriatic Croatia as a tourist destination regarding energy. This paper makes a contribution to understanding the state of awareness of environmental issues among tourism managers in the Adriatic region of Croatia.

Each new scientific paper constitutes a contribution in the theoretical and empirical sense as it provides scientists with the opportunity to expand on this subject, and at the same time, it provides managers in tourism the opportunity to evaluate their own education and knowledge about the subject matter. The results of this study have a high practical value as they ensure adopting and implementing energy management for achieving sustainable development. Sustainable development is a priority according to Croatian strategic documents. In the Croatian Tourism Development Strategy [

53], sustainable development represents the foundation for implementing sustainable energy development. It is exactly for those reasons that the poor level of informedness of managers in tourism when it comes to matters of energy indicates that fast and efficient action is required. The respondents in this study showed a satisfactory level of education (college or university degree) and an age indicating work experience. Despite that, they showed poor informedness pertaining to energy issues in tourism. These results show that there should be continuous education for managers but also better and continuous promotion of such education programs by the government and the Ministry of Tourism, Ministry of Economy, all the way down to regional energy agencies and private entrepreneurs providing services related to energy efficiency, renewable energy sources, and other matters. Additionally, the results can be used as a basis for selecting the optimal model of energy management and defining how it will operate in particular tourist destinations or even in particular tourism facilities.

These results are especially significant as they represent essential premises and a relevant documentation foundation for making business decisions concerning energy management. Scientists and managers can use these results to consider the necessary actions in terms of investments, organization, education, staffing, and other aspects of energy management in accordance with the specificities of their business and the environment.

Facilities, based on their environment, climate conditions, and purpose, have to use as much natural lighting and ventilation as possible in order to achieve energy efficiency. Controlling water consumption is paramount, as well as motivating guests to reduce consumption and participate in various activities. Facilities should purify wastewater and use it for irrigation. Facilities should also collect rainwater, especially those facilities that have limited access to water. It is necessary to sort waste and recycle, as well as to use ecological products, eco-friendly transportation, alternative fuel, etc., as much as possible. When building or refurbishing facilities, natural and local materials that are not harmful to the environment should be used, as well as technologies that enable more efficient management of the facility and result in reducing the negative effects on the environment. Larger tourism facilities, especially parts of hotel chains, already apply most of the aforementioned activities and measures, and they dedicate more effort to environmental protection compared to individually owned facilities. This is caused by potentially diverse factors, but the most important are larger financial assets and investment funds at their disposal, and a desire to create a better image as society, in general, exerts more pressure on large companies to conduct business in a socially responsible way and to achieve sustainable development. Furthermore, sustainability results in a more efficient business and a significant reduction in a facility’s expenses. The three-pillar concept of sustainability—social, economic, and environmental—commonly represented by three intersecting circles with overall sustainability at the center, has become ubiquitous [

54]. Investments in energy efficiency can be expensive. Therefore, a lack of funding and lack of subsidies, particularly when it comes to energy efficiency and renewable energy sources, certainly discourage companies from getting involved. The findings in this paper suggest that public policy and business advice in this area should perhaps focus more intently on personal values and a sense of being able to contribute to environmental protection in their engagement with small businesses.

Ultimately, and perhaps most importantly, all stakeholders from the national to the local level need to work on raising awareness regarding the importance of energy issues, and not just because of managers themselves who make the decisions but also because of their employees, tourists, and residents that make up an interconnected tourist system.

Limitations and Future Research

It is important to note that the sample was drawn only from the region of Adriatic Croatia, and the questionnaire was filled out only by managers related to tourism. The results should thus not be generalized to managers in other sectors or other parts of the world. Despite this caveat, we fully expect that other researchers will be able to corroborate the conclusions laid out in this study in larger samples of managers over longer periods. We propose that further studies be conducted for the entire territory of Croatia, i.e., to encompass Continental Croatia in the next study to get unified results for the whole country. Comparisons can also be made with other regions on the NUTS-2 level. Further research can also include polling tourists and residents about energy issues in tourism. Based on various research goals, further research can also be built around the questions that may be posed in the questionnaire.