Models of Intersectoral Cooperation in Municipal Health Promotion and Prevention: Findings from a Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Background

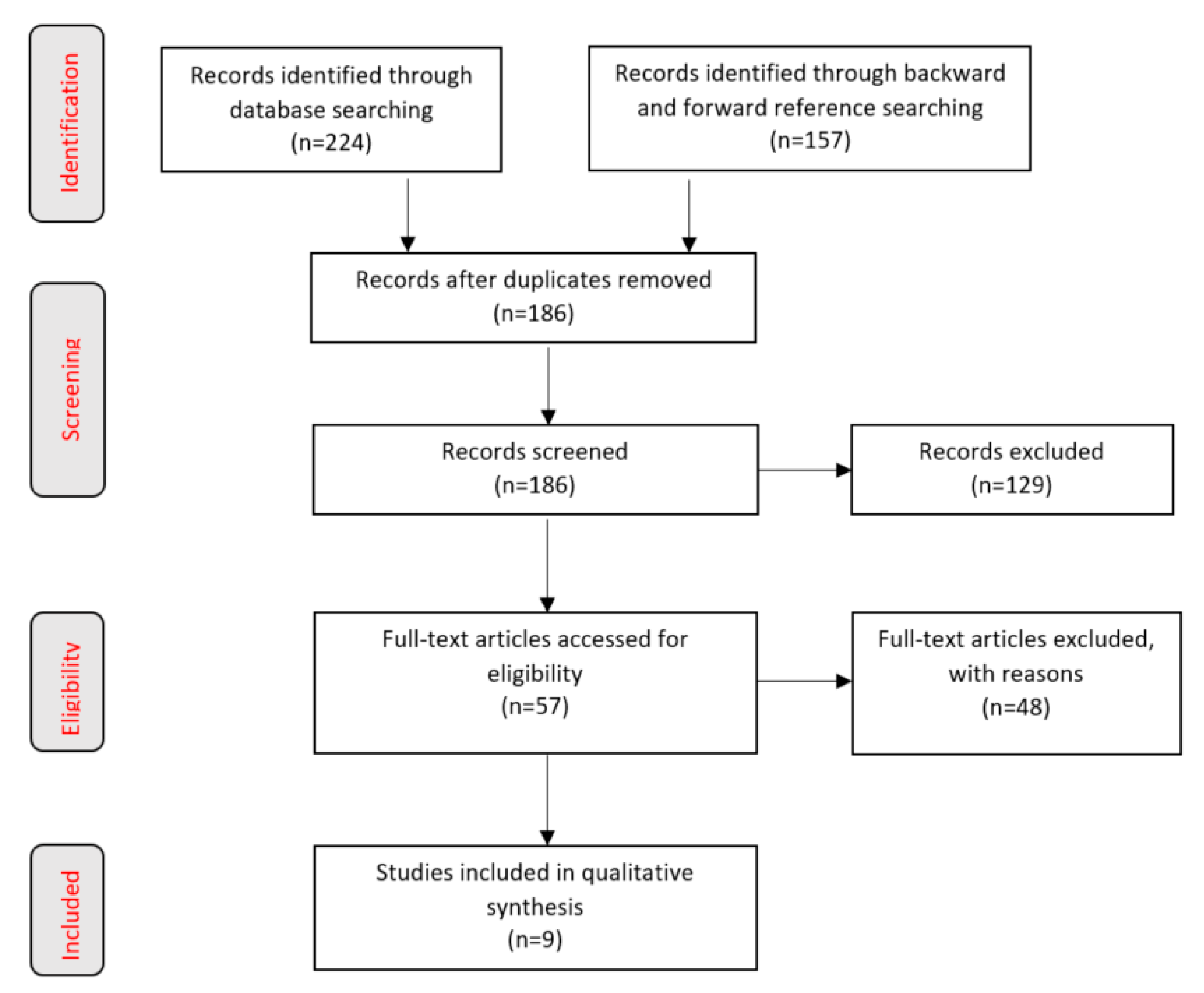

2. Methodology

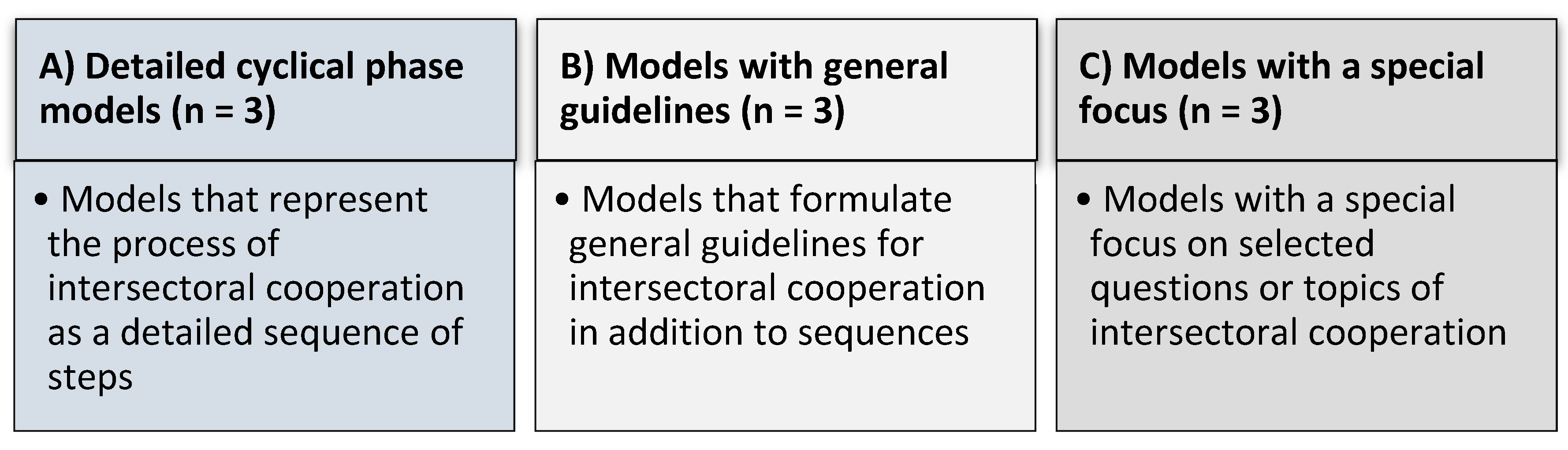

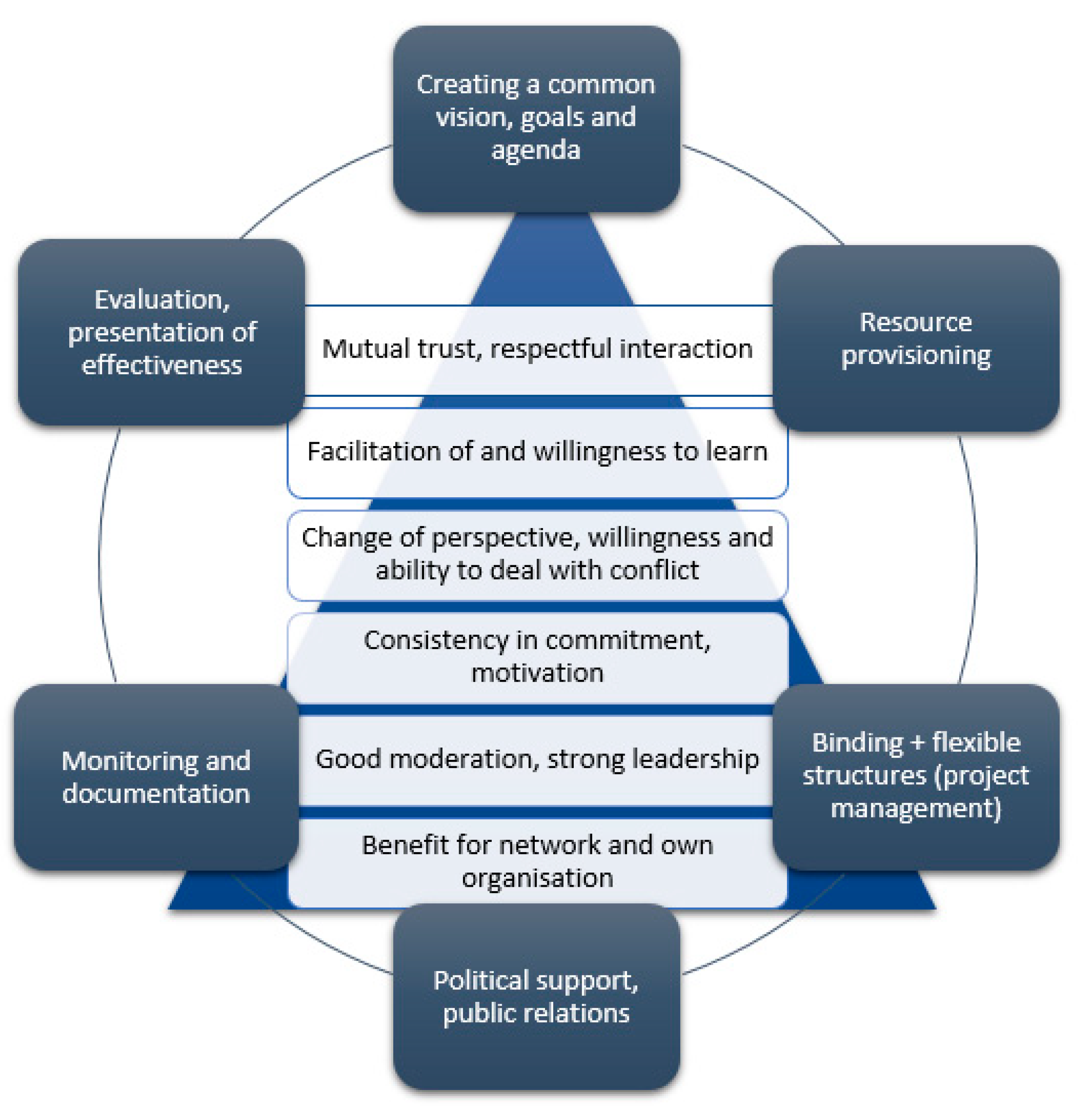

3. Results: Models of Intersectoral Cooperation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lampert, T.; Hoebel, J.; Kroll, L.E. Soziale Unterschiede in Deutschland: Mortalität und Lebenserwartung. J. Health Monit. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Review of Social Determinants and the Health Divide in the WHO European Region; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M. The health gap: The challenge of an unequal world. Lancet 2015, 386, 2442–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N.J.R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Basu, N.; Baldé, A.B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J.I. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet 2018, 391, 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobollik, M.; Kabel, C.; Hornberg, C.; Plaß, D. Übersicht zu Indikatoren im Kontext Umwelt und Gesundheit. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2018, 61, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claßen, T.; Bunz, M. Einfluss von Naturräumen auf die Gesundheit–Evidenzlage und Konsequenzen für Wissenschaft und Praxis. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2018, 61, 720–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Koch-Institut. Gesundheit in Deutschland; Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Gemeinsam Getragen von RKI und Destatis; Robert-Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Koch-Institut. KiGGS Welle 2—Erste Ergebnisse aus Querschnitt-und Kohortenanalysen. J. Health Monit. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupfer, A.; Gamper, M. Migration als gesundheitliche Ungleichheitsdimension? Natio-ethno-kulturelle Zugehörigkeit, Gesundheit und soziale Netzwerke. Soz. Netzw. Gesundh. Ungleichheiten 2020, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewerkschaftsbund, D. Gesundheitsrisiko Arbeitslosigkeit—Wissensstand, Praxis und Anforderungen an eine Arbeitsmarktintegrative Gesund-Heitsförderung. 2010. Available online: http://www.forschungsnetzwerk.at/downloadpub/2010_dgb_Gesundheitsrisiko_arbeitslosigkeit.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Krug, G.; Brandt, S.; Gamper, M.; Knabe, A.; Klärner, A. Arbeitslosigkeit, soziale Netzwerke und gesundheitliche Ungleichheiten. Soz. Netzw. und gesundheitliche Ungleichheiten. 2020, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastl, J.M. Einführung in die Soziologie der Behinderung., 2nd ed.; Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brandhorst, A. Kooperation und Integration als Zielstellung der gesundheitspolitischen Gesetzgebung. Koop. Integr. Unvollendete Proj. Gesundh. 2017, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M. Levelling up (Part 2): A Discussion Paper on European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health. 2006. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/107791/E89384.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- World Health Organization. Targets and Beyond—Reaching New Frontiers in Evidence. The European Health Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/european-health-report-2015-the.-targets-and-beyond-reaching-new-frontiers-in-evidence.-highlights (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Böhme, C.; Stender, K.-P. Gesundheitsförderung und Gesunde/Soziale Stadt/Kommunalpolitische Perspektive. 2015. Available online: http://www.bzga.de/leitbegriffe (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Köckler, H. Sozialraum und Gesundheit. Gesundheitswissenschaften. 2019, pp. 517–525. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-662-58314-2_48 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Böhme, C.; Bunge, C.; Preuß, T. Umweltgerechtigkeit in der Stadt—Zur integrierten Betrachtung von Umwelt, Gesundheit, Sozialem und Stadtentwicklung in der kommunalen. Umweltpsychologie 2016, 20, 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, U.; Röding, D.; Kruse, S.; Quilling, E. Modelle und Evidenzen der Intersektoralen Kooperation in der Lebensweltbezogenen Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. 2018. Available online: https://www.gkv-buendnis.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Publikationen/Bericht_Intersektorale-Kooperation_2019.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Praxisdatenbank Gesundheitliche Chancengleichheit. 2019. Available online: https://www.gesundheitliche-chancengleichheit.de/praxisdatenbank/ueber-die-praxisdatenbank/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Soziale Lage und Gesundheit: Ursachen. Available online: https://www.gesundheitliche-chancengleichheit.de/kooperationsverbund/hintergruende-daten-materialien/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Brown, E.C.; Hawkins, D.; Rhew, I.C.; Shapiro, V.B.; Abbott, R.D.; Oesterle, S.; Arthur, M.W.; Briney, J.S.; Catalano, R. Prevention system mediation of Communities That Care effects on youth outcomes. Prev. Sci. 2014, 15, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downey, L.H.; Thomas, W.A.; Gaddam, R.; Scutchfield, F.D. The relationship between local public health agency characteristics and performance of partnership-related essential public health services. Health Promot. Pract. 2013, 14, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenbakkers, M.; Jansen, M.; Maarse, H.; de Vries, N. Challenging Health in All Policies, an action research study in Dutch municipalities. Health Policy 2012, 105, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, I.; Heinrichs, N. Populationseffekte Einer Flächendeckenden Implementierung Familienbasierter Präventionsprogramme. 2016. Available online: https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/full/10.1026/1616-3443/a000344 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Quilling, E.; Kruse, S. Evidenzlage Kommunaler Strategien der Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung: Eine Literatur- und Datenbankrecherche (Rapid Review). 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341670274_Evidenzlage_kommunaler_Strategien_der_Praven_on_und_Gesundheitsforderung_Eine_Literatur-_und_Datenbankrecherche_Rapid_Review (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Chircop, A.; Bassett, R.; Taylor, E. Evidence on how to practice intersectoral collaboration for health equity: A scoping review. Crit. Public Health 2015, 25, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, V.B.; Oesterle, S.; Hawkins, J.D. Relating coalition capacity to the adoption of science-based prevention in communities: Evidence from a randomized trial of Communities That Care. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2015, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landschaftsverband Rheinland, K.K.i.L.-L. Präventionsnetzwerke und Präventionsketten erfolgreich koordinieren. Eine Arbeitshilfe aus dem LVR-Programm. 2017. Available online: https://www.lvr.de/de/nav_main/jugend_2/jugendmter/koordinationsstellekinderarmut/koordinationsstellekinderarmut_1.jsp (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Fawcett, S.; Schultz, J.; Watson-Thompson, J.; Fox, M.; Bremby, R. Peer Reviewed: Building Multisectoral Partnerships for Population Health and Health Equity. 2010; Volume 7. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995607/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Towe, V.L.; Leviton, L.; Chandra, A.; Sloan, J.C.; Tait, M.; Orleans, T. Cross-sector collaborations and partnerships: Essential ingredients to help shape health and well-being. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, C.E.; Mowat, D.L.; Keen, D. Pathways to policy: Lessons learned in multisectoral collaboration for physical activity and built environment policy development from the Coalitions Linking Action and Science for Prevention (CLASP) initiative. Can. J. Public Health 2017, 108, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrimali, B.P.; Luginbuhl, J.; Malin, C.; Flournoy, R.; Siegel, A. The building blocks collaborative: Advancing a life course approach to health equity through multi-sector collaboration. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montigny, J.G.; Desjardins, S.; Bouchard, L. The fundamentals of cross-sector collaboration for social change to promote population health. Glob. Health Promot. 2019, 26, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.D.; Greene, J.K.; Abramowicz, A.; Riley, B.L. Strengthening the evidence and action on multi-sectoral partnerships in public health: An action research initiative. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research. Policy Pract. 2016, 36, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L.M.; Finegood, D. Cross-sector partnerships and public health: Challenges and opportunities for addressing obesity and noncommunicable diseases through engagement with the private sector. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbrock, R. Public health as a social innovation. Gesundh. Bundesverb Arzte Ofentl. Gesundh. (Ger.) 1995, 57, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbrock, R.; Gerlinger, T. Gesundheitspolitik: Eine Systematische Einführung; Verlag Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Scoping Review: |

|---|

| Only German and English language publications were included; publications in other languages were excluded. |

| Only publications published between 2010 and 2018 were included. |

| Reviews, study results, grey literature, and reports were included in the full text analysis. |

| Abstracts, letters, comments and editorials, and contributions to the announcement of studies that do not yet show results were excluded. |

| Only publications that specifically refer to intersectoral cooperation in prevention and health promotion were included in the full text analysis. Publications that deal with intersectoral cooperation in the context of patient care or the rehabilitative and nursing care system were systematically excluded. |

| Included were publications that refer to industrial nations with comparable care structures; excluded were publications that refer to regions and/or populations that do not allow a transfer to German conditions. |

| Both narrative and systematic reviews were included as well as qualitative and quantitative studies and reports on approaches and strategies of intersectoral cooperation, their evaluation and effectiveness, success factors, and theoretical approaches and models. |

| The search strings were designed in such a way that only publications containing the search terms in the title are considered. |

| For the sub-question on approaches and theoretical models examined here, only those texts describing theoretical models and approaches were included in the analysis. |

| Author/Model | Subject | Quintessences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category A | Shapiro et al. (2015): Communities That Care® [28] | Strengthening the coalition capacity and science-based health promotion of adolescents in the community | Core of the CTC® Program: 5-phase procedure from the founding of an alliance to evaluation. The success components of the CTC® Program are the consistent, science-based survey of the concrete, specific needs and the orientation towards evidence-based measures |

| Landschaftsverband Rheinland (2017): Strategy cycle network cooperation [29] | Networks against child poverty as an integrated overall strategy/prevention chains in municipalities in the Rhineland. | 10-step strategy cycle including clarification of mission and mission statement development, network analysis and steering group formation, involvement of policymakers and the public, needs assessment, implementation, monitoring and evaluation to assess effectiveness | |

| Fawcett et al. (2010): Institute of Medicine Framework for Collaborative Action [30] | Successful interventions in the public health sector as a guideline model for communities. | 12-step model; elements: clear responsibilities and action plans, resources: training and technical support, creating good cooperation conditions and appropriate financing, participatory evaluation systems, systematic measurement of progress | |

| Category B | Towe et al. (2016): Health Action Framework [31] | Improving health and well-being through the Health Action Framework. | Three key requirements for collaborations: (1) number, breadth and quality of partnerships, (2) adequacy and reliability of investment, (3) guidelines to promote collaboration. |

| Politis et al. (2017): CLASP-Pathways to policy [32] | Strategic pathways in the CLASP program for physical activity and built environment; success factors for policy changes. | Building relationships and sharing expertise and new or expanded staff positions, creating and sharing approaches and resources, enabling knowledge to be gained on effectiveness, building genuine willingness to cooperate and formalized partnerships and cooperation structures. | |

| Shrimali et al. (2013): Building Blocks Collaborative [33] | Strategic partnerships to improve health equity in low-income communities | (1) Forging alliances and visions, (2) Broadening perspectives on health conditions, (3) Project development. Success factors: strong leadership, committed employees, ownership, flexible partnership structure, support for capacity building, promotion of learning, exchange and development, project resources. | |

| Category C | De Montigny et al. (2017): Fundaments of cross-sector collaboration for health promotion [34] | Inter-sectoral cooperation with a special focus on maintaining motivation, willingness to learn and sustainability | Framework of sustainable cooperation: common agenda, appreciation of different perspectives (including those of the actors), flexibility and positive effects for partner organizations themselves, open, transparent communication and constant willingness to learn. |

| Willis et al. (2016): Learning and improvement strategy [35] | Learning and development strategy of the Canadian initiative for multisectoral partnerships for the prevention of chronic diseases as an action research project | Understanding of administrative actions, trust in cooperation and stable cooperation structures, visualization of existing resources and their creation, capacity building and sufficient time perspectives for successful networking. These elements can be made useful as further training modules for process partners. | |

| Johnston and Finegood (2015): Model of integrating cross-sector Partnership [36] | Partnerships between the health sector and the private sector to prevent obesity and chronic diseases. | Challenges, risks and benefits of cross-sector partnerships as integrated forms of action and organization. Core elements: trustful cooperation, active, moderating handling of conflicts of interest, consistently applied monitoring and evaluation of interventions. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quilling, E.; Kruse, S.; Kuchler, M.; Leimann, J.; Walter, U. Models of Intersectoral Cooperation in Municipal Health Promotion and Prevention: Findings from a Scoping Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166544

Quilling E, Kruse S, Kuchler M, Leimann J, Walter U. Models of Intersectoral Cooperation in Municipal Health Promotion and Prevention: Findings from a Scoping Review. Sustainability. 2020; 12(16):6544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166544

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuilling, Eike, Stefanie Kruse, Maja Kuchler, Janna Leimann, and Ulla Walter. 2020. "Models of Intersectoral Cooperation in Municipal Health Promotion and Prevention: Findings from a Scoping Review" Sustainability 12, no. 16: 6544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166544

APA StyleQuilling, E., Kruse, S., Kuchler, M., Leimann, J., & Walter, U. (2020). Models of Intersectoral Cooperation in Municipal Health Promotion and Prevention: Findings from a Scoping Review. Sustainability, 12(16), 6544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166544