Abstract

The last decade has seen a flourishing of social agriculture cooperatives and the exponential growth of the craft beer sector in Italy. Social microbreweries (social cooperatives that operate in the craft beer sector) have started emerging but have not yet been a focus of research. This paper explores the relationship between social agriculture and microbreweries in Italy, bridging the gap between social agricultural cooperation and craft beer production. It deploys a qualitative multiple case study methodology, based on the in-depth analysis of three case studies: Vecchia Orsa, one of the oldest social microbreweries in Italy; Pintalpina, which operates in a unique alpine setting; Articioc, established by a group of friends with a love of craft beer. This research suggests that the craft beer sector provides important opportunities for social innovation in social cooperatives, with a particular focus on the work integration of vulnerable people. In addition, this paper highlights different pathways for scaling social microbreweries, including focusing on organisational growth (growing the size of the business), scaling out (impacting greater numbers) and scaling deep (impacting cultural roots). Different scaling approaches are united by a common scaling strategy: network and partnership building. This emerges as an essential action to increase the impact of social microbreweries.

1. Introduction

In recent years, following the 2008 economic crisis, the inability of the public sector to provide financially viable social services has become apparent, particularly in rural areas [1]. In light of this, new hybrid solutions have been trialled, combining different environmental and socio-economic elements, often guided by civil society alliances, to support local development pathways. The growing phenomenon of social farming is a clear example of this transition towards multifunctional strategies in rural areas.

In this context, this paper focuses on social farming in Italy (known as social agriculture) from the unique perspective of the craft beer sector. It aims at exploring the link between social agriculture and microbreweries, bridging the gap between craft beer production and social agricultural cooperation. In doing so, this paper seeks to shed light on the role of social microbreweries offering new work integration opportunities for vulnerable people in rural areas and to highlight different strategies for scaling social microbreweries. In a context of flourishing social agriculture and exponential growth of the craft beer sector, how are social microbreweries seeking to scale? In other words, how are they seizing the opportunity to develop out of their niche, improving the effectiveness of their activities and fulfilling the needs they were constituted to address?

This paper analyses the scaling strategies of three case studies: Vecchia Orsa, one of the oldest social microbreweries in Italy; Pintalpina, which operates in a unique alpine setting; Articioc, established by a group of friends with a love of craft beer. While focusing on local experiences, this paper fits within the global debates of social farming and social innovations’ scalability, providing relevant insights for social enterprises and social farming initiatives worldwide. In particular, this research (i) highlights how the craft beer sector provides important opportunities for social innovation in social cooperatives, with a particular focus on the work integration of vulnerable people; (ii) identifies different pathways for scaling social microbreweries, including focusing on organisational growth (growing the size of the business), scaling out (impacting greater numbers) and scaling deep (impacting cultural roots); (iii) reveals how network and partnership building is a key scaling strategy to increase the impact of social microbreweries.

The originality of this paper lies in the combination of social agriculture and craft beer production. These are two growing sectors and widely explored in the literature, but seldom considered together. Social microbreweries offer important opportunities for the development of social cooperatives (to enhance their economic sustainability by penetrating the craft beer market), for microbreweries (to strengthen their social orientation by creating new working opportunities for vulnerable people), and for rural areas (to support their local development by starting up new socio-economic activities).

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 explores social microbreweries in Italy as the interface between social agriculture and the craft beer sector. First, it provides an overview of social agriculture and social cooperation in Italy. Second, it focuses on the rise of microbreweries in Italy. Third, it introduces social microbreweries and the key challenge of scaling. Section 3 includes the methodology and introduces the three cases studied by this research (Pintalpina, Articioc and Vecchia Orsa). Section 4 provides detailed insights on the findings, for each social microbrewery analysed. A discussion of the findings is provided in Section 5.

2. Social Microbreweries: When Social Agriculture Meets the Craft Beer Sector

2.1. Social Agriculture and Social Cooperation in Italy

Social farming is a multifunctional strategy, bridging social and agricultural practices. It offers new solutions to socio-economic and environmental challenges, promoting the long-term sustainable development of rural areas (e.g., through biodiversity conservation, the prevention of depopulation and preservation of the cultural heritage of local communities) [2,3]. Social farming positively contributes to a more balanced use and allocation of different local resources and it is also a system of food provisioning, often as an alternative to long supply chains. It is able to support families and small farms, generating new employment opportunities and social services, and to enhance the social capital accumulated at the local level by building new relationships (among different local actors in the public, private and civil society sectors) [4,5].

A broadly accepted definition within the literature defines social farming as ‘the multifunctional use of agriculture, frequently introduced at a “grass-roots level” […] in order to provide services for less empowered people and for the community by mobilising new resources and designing innovative farm services’ [4]. While an internationally acknowledged definition of social farming has not yet been developed, a wide range of literature explores social farming practices in terms of ‘care farming’, ‘green care’, and ‘farming for health’ [2,6,7]. In Italy, social farming is specifically referred to as ‘agricoltura sociale’, which is literally translated as ‘social agriculture’ [8] (In this paper, we choose to adhere to the literal translation. Therefore, we only refer to ‘social agriculture’ in relation to the Italian context).

In 2015, Italy approved a law on social agriculture (Law n. 141/2015), which regulated the sector, whilst providing it with a clear definition. According to its normative dispositions, social agriculture can encompass an extensive range of activities undertaken in the framework of the rural economy (e.g., arable farming, animal husbandry and agri-tourism), which are grouped in four categories. First, activities aimed at the social and work-integration of vulnerable people into the agricultural sector. Second, social services for local communities through deploying tangible and intangible agricultural resources (e.g., farming land and farming skills). Third, services supporting medical-rehabilitative therapies. Fourth, projects aimed at environmental and food education, the safeguarding of biodiversity and knowledge of the territory. Through a combination of these activities, social agriculture enhances the multifunctional potential of agriculture, integrating strictly agricultural services, such as food production, with social, health, educational, cultural, job placement and recreational initiatives.

In the Italian context, the main providers of social farming can be divided into three categories: public authorities, not-for-profit and for-profit enterprises. The not-for-profit category mainly includes social cooperatives, which operate in the market with the specific aim of providing social/care services and/or work integration of vulnerable people. However, this category may also include volunteer-based associations. (Social cooperatives are the most widespread form of social enterprise in Italy [9,10]. They are regulated by the Italian Law n. 381/91, which defines their purpose as ‘to pursue the general interest of the community in human promotion and in citizens’ social integration through: (a) managing socio-health and educational services; (b) conducting several activities—agricultural, industrial, commercial or services—with the aim of the work-integration of disadvantaged people’. The same law establishes that vulnerable people (in Italian, ‘persone svantaggiate’) must be at least thirty percent of the workers in the cooperative be members of the cooperative itself. The article 4 of the same law, defines vulnerable people as ‘the physically, mentally and sensory impaired, the former patients of psychiatric hospitals, including judicial ones, the persons undergoing psychiatric treatment, drug addicts, alcoholics, minors of working age in situations of family difficulty, people detained or interned in prisons, convicts and internees admitted to alternative measures to detention and work outside’ (Law n. 381/91, art. 4). The Italian Law n. 381/91 identifies two types of social cooperative. Type A focuses on socio-healthcare and educational services delivery. Type B focuses on the work integration of vulnerable people). The for-profit category mainly includes private farms and agricultural cooperatives, which promote social farming as part of a multifunctional strategy. Alongside these main actors, public institutions play a key complementary role, as triggers, intermediaries or partners in social farming initiatives [5].

A recent survey on social agriculture in Italy reveals that, in 2016, about 1200 social agricultural initiatives were active throughout the country. Social agriculture providers included, amongst others, 430 social cooperatives, 336 farms and 153 public institutions [11]. Although social cooperatives are the most widespread actor delivering social agricultural services, the law on social agriculture (Law n. 141/2015) only applies to those social cooperatives where greater than 30% of annual turnover is derived from agricultural activities.

Social agriculture in Italy is a fast-growing phenomenon. A total of 108 social cooperatives were engaged in agricultural activities in 1993 and this number has quadrupled over the last fifteen years [11,12]. However, despite this impressive growth rate, little research has focused on social cooperatives delivering social agriculture activities and associated challenges and opportunities. The most recent report focusing on social agricultural cooperatives estimated the economic value of their production at €182 million in 2009 [12], while the activities they undertook were estimated to have involved between 15,000 and 20,000 vulnerable people (most with a physical or mental disability or drug addicts) in 2005 [13].

2.2. The Rise of Microbreweries in Italy

In recent years, the practice of craft beer production has grown exponentially. The ‘craft beer revolution’ [14,15] boosted the brewery sector, encouraging the founding of many new craft workshops all over the world, so-called ‘microbreweries’ [15,16,17]. Extensive literature has focused on microbreweries and on the rapid growth of the craft beer sector in recent years. Some studies explore the potential of craft beer production to generate competitive advantage in the independent food and beverage industries [18,19,20]; others analyse the organizational identity of microbreweries [21], their ability to strengthen relationships with customer and employees, building a new local identity [22,23] and their general performance [24]. More recently, the literature has focused on the impacts of microbreweries on local economies [25,26,27,28,29,30,31] and on the relationship between craft beer production and other economic sectors in rural areas, such as tourism [32,33,34,35,36,37], including shedding light on which factors influence brand loyalty [38]. Finally, the rise of microbreweries has been analysed in relation to consumption patterns [39,40,41,42], the reuse of abandoned buildings and revitalization of urban neighbourhoods [43,44], and their sustainability at the local and global levels [45,46,47,48]. In general, microbreweries emerge from the literature as local manifestations of cultural heritage. Their constitution is considered as an opportunity to restore “beer to its rightful place as a local business and a product that says something about its hometown and region. [...] The craft brewers are taking beer back to its artisanal roots, the way many local bakers are making bread and cheese makers are making cheese” [17] (p. 1).

According to the American Brewers Association (ABA), a microbrewery (or craft brewery) is (i) small (annual production less than 6 million barrels), (ii) independent (less than 25% of the craft brewery is owned or controlled by an alcohol industry member that is not itself a craft brewer) and (iii) traditional (a brewer that has a majority of its total beverage alcohol volume in beers whose flavour derives from traditional or innovative brewing ingredients and their fermentation) [49]. In Europe, several definitions of craft breweries exist, each in relation to different national laws. In Italy, according to Law 154/2016, art. 35, a microbrewery is defined as a:

small independent producer which is legally, economically, and physically independent of any other brewery, that uses structures physically distinct from those of any other brewery, which does not operate under a license to use the intangible property rights of another producer and whose annual production does not exceed 200,000 hectolitres, including in this amount the quantities of beer produced on behalf of third parties.

Even if the Italian craft beer scene is characterised by the absence of a historic brewing tradition, the number of breweries has proliferated by +470% in ten years, from 132 in 2005 to 757 in 2016, placing Italy in fourth position in Europe, after the UK, Germany and France [50,51,52]. In 2017, the number of breweries was 1008, increasing further in 2018. In particular, what it is significant about the Italian brewing industry is the prominence of ‘micro’ production. According to Assobirra [53], there were 862 microbreweries in Italy in 2018. This number includes: 692 microbreweries (production only or with at least one ‘tap room’) and 170 brewpubs (microbreweries that sell 25% or more of their beer on site). This number does not include 540 beer firms, which are brewing companies that do not have their own production site (microbirrifici.org). In ten years, between 2008 and 2018, the total number of microbreweries quadrupled, growing from 206 to 862 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of microbreweries in Italy (1996–2018).

This ‘revolution’ originated from a small group of people led by a passion for beer and the means to set up a production site. This passion fast became a business able to provide opportunities for employment in local communities. Breweries with more than 50 employees (i.e., industrial operators) represent only 1.5% of the total number of breweries in Italy, while those with less than five employees (craft microbreweries) represent 84%. Comparing 2017 with 2015, the breweries that employ 1 to 5 employees grew by 57%, creating 551 new jobs (+60%), while those with more than 50 employees increased by 36%, creating 206 new jobs (+4%) [53].

2.3. Scaling Social Microbreweries

In Italy, social agriculture meets the ‘craft beer revolution’ in the social microbrewery. A social microbrewery can be defined as a social cooperative (as regulated by Italian Law n. 381/91) that operates in the craft beer sector. The growth of microbreweries has become increasingly relevant, not only because it generates economic value (e.g., new firms and employment), but also because it creates significant opportunities for local development, including the generation of social value (e.g., new opportunities for work integration). Despite the craft beer sector being an important opportunity for the generation of social value—and despite both social farming and microbreweries rapidly developing in Italy—social microbreweries still occupy a small niche.

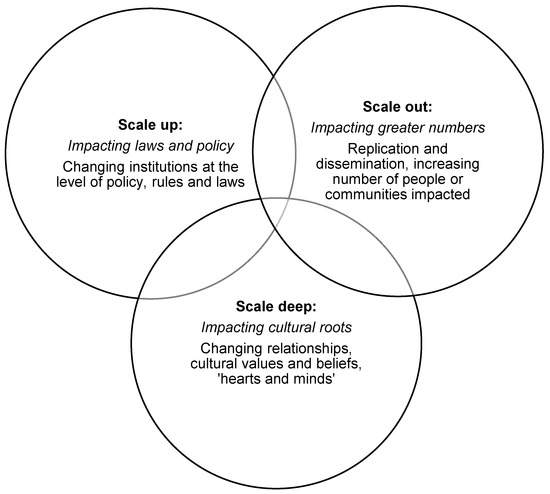

A major challenge for social cooperatives and social enterprises is to scale [54,55,56]. That is, to move out of their niche [57], fulfilling their transformative potential for systemic change [58]. Scaling social agricultural activities involves unique managerial challenges, especially when they are delivered by social cooperatives, as they are organisations characterised by the coexistence of commercial and social aims (i.e., operating in the market with a not-for-profit identity). This means that, while seeking to increase the scope of their actions, they should find the right balance between strategic decisions guaranteeing their economic sustainability and those that preserve their identity, including their social mission, democratic governance and local focus. Therefore, scaling social breweries is not the same as scaling for-profit enterprises. In fact, the very meaning of ‘scale’ varies widely in different organisational contexts. While in for-profit settings, to scale often means to achieve organisational growth, in the context of social innovation, scaling encompasses a much wider spectrum of practices and it cannot be used as a synonym for growth [59]. The Centre for Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship (CASE) at Duke University, states that social innovations have scaled "when their impact grows to match the level of need" [59] (p. 10). Therefore, to increase the impact of their activities, social breweries require finding the right balance between different scaling strategies, over and above organisational growth. Riddell and Moore [60] have identified three main scaling approaches for growing the impact of social enterprises. These include scaling ‘up’, ‘out’ and ‘deep’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scaling out, scaling up and scaling deep for social innovation [60].

Scaling ‘up’ seeks to influence laws and policies; scaling ‘deep’ to produce an impact on cultural roots; scaling ‘out’ to achieve geographical replication and dissemination [60]. Each type of scaling involves specific strategies, such as advocacy efforts (i.e., for scaling up), storytelling to shift norms and beliefs (i.e., for scaling deep) and adaptation to different contexts (i.e., for scaling out). Beside this triple approach, cross-cutting strategies for scaling include making scale a conscious choice, analysing root causes and clarifying purpose, building networks and partnerships, seeking new resources, commitment to evaluation and institutional resources [60].

3. Methodology

This research deploys a multiple case study approach, a type of qualitative empirical investigation that explores a phenomenon in the context in which it is generated and reproduced [61]. This methodology is useful to investigate emerging social phenomena (i.e., social microbreweries) and complex organisational dynamics (i.e., scaling strategies), where little or no data exists beforehand. While extensive research has been produced on social farming [4,6,8] and the rise of microbreweries [16,17,18,19], social microbreweries are still uncharted territory. In addition, a multiple case study methodology is suitable to study organisations strongly embedded in the local contexts in which they operate (i.e., social microbreweries) as it allows the investigation of deep endogenous and exogenous factors influencing the development of specific organisations and the relationship they have with the local community and stakeholders [62].

Since no research focuses on social microbreweries, it is difficult to identify these initiatives and to quantify the phenomenon. Combining different available data (i.e., sourced from the Aida—Bureau Van Dijk database and online), only 10 social breweries operating in Italy were identified (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Social microbreweries in Italy.

Excluding cases with a scope broader than beer production (e.g., Pausa Caffé operates as a caterer in the wider food sector) and those operating in urban areas (e.g., Vale La Pena), and targeting those focusing on craft beer production and operating in rural territories, the search was narrowed down to three case studies. Selection criteria also considered data accessibility, focusing on organisations ‘easy to get to and hospitable to our enquiry’ [63]. Selected cases include Vecchia Orsa, one of the oldest social microbreweries in Italy, Pintalpina, which operates in a unique rural setting (i.e., alpine), and Articioc, officially established in 2014, building on a pre-existing experience of craft beer production.

Data was collected between November 2018 and January 2020 using a preliminary questionnaire, followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews with managers, workers and volunteers in each organisation, in order to outline their main characteristics (i.e., reasons behind the foundation, constitution process, activities and services provided, local stakeholders involved and scaling strategies). Documentary evidence such as newspaper articles, online resources and company documents (e.g., balance sheets and social accounting, reporting, documents, etc.) complement the data collection. Data was analysed using both within-case and cross-case analysis, to generate in-depth results from studied cases. The analytical process allows the identification of the conditions under which social microbreweries thrive and scale, fulfilling their potential to innovate and create new job opportunities for vulnerable people.

4. Findings

The following sections focus on each case study in turn. First, Pintalpina, which is a mountain social microbrewery, deeply embedded in the rural traditions of Valtellina (the alpine area in which it operates and from which the prime ingredients used in the brewing process are sourced). Second, Articioc, established by a group of friends with a love of craft beer and developed through participation in strong local networks. Third, Vecchia Orsa, a long established social microbrewery, characterised by the excellence of its beers and a continuous and progressive expansion. Table 3 and Table 4 guide the reader through understanding each case. Table 3 includes a brief summary of the ‘main characters’ in each case study. It outlines the names of each microbrewery and related organisations.

Table 3.

Key names and organisations.

Table 4.

Scaling social microbreweries.

Regarding financial figures, data retrieved from the Aida—Bureau Van Dijk database shows the three cooperatives have closed the 2018 financial year (latest available data) with a positive net profit. Elianto (Pintalpina) and Articioc registered an average net profit of €10,794 in 2018, while Arca di Noè recorded a net profit of €95,615. However, the latter number includes other activities carried out by the cooperative besides the Vecchia Orsa social microbrewery. Moreover, Elianto and Articioc registered an average value of production of €155,000 in 2018. Arca di Noè’s social report (Available online. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/arcadinoecoop.soc./docs/arca_bilancio_018_issuu. Last accessed on 11th June 2020) indicates in the section ‘food and beverage’ (including Vecchia Orsa social microbrewery and Al Bineri restaurant, selling Vecchia Orsa beers) that the value of production was €157,000 in 2018. In addition, Elianto and Articioc’s average net assets amounted to €18,078 in 2018, while Arca di Noè’s (aggregated) net assets totalled €1,205,674.

Table 4 includes a brief overview of the key scaling approaches and related strategies in each case study. Approaches and strategies, presented in-depth in the present section, are further discussed in the next.

4.1. Pintalpina

The social microbrewery Pintalpina is a project of the social cooperative Elianto. The project was launched in 2014, with the aim of creating social value at a local level, through the work-integration of vulnerable people. Through the production of artisanal beer, the brewery offers young people with different disabilities the opportunity to find a job and to have an active social role that is recognised by the community.

Our aim is to focus on the person and to focus on their integration with the wider community, to avoid creating disability ghettos. Work [...] represents an essential means to achieve the right of citizenship and it is a key element of aldult identity, a very important factor of socialisation and self-realisation. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

We want to offer a protected and stimulating work environment for training and work placements of young people with different skills who, once they leave school, risk being excluded from the world of work. We want to help them enhance their diversity, to demonstrate that their skills can also be useful in creating economic value and promote their social integration. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

The headquarters of the social microbrewery is in Chiuro: a small municipality in the Province of Sondrio (Lombardy, Italy), in the heart of Valtellina: a mountain area bordering Switzerland, rich in natural resources, craft and food specialties and cultural heritage. At the very beginning, the creation of a social microbrewery project originated from an idea formulated by three friends and fellow educators. They worked for the Prometeo-Onlus Association, which was establised in December 2005, in Sondrio, with the aim of assisting disabled people and, in particular, organising leisure activities and summer holidays. In 2013, after 8 years operating in that sector, they decided to invest in the creation of a social microbrewery, as a new way to engage with vulnerable young people while providing training and offering job opportunities. The idea of the social microbrewery came after careful market research and an evaluation of which new economic sector for work-integration could be based on the specific features offered by the Valtellina area.

We immediately thought of productive activities related to agriculture, but the cultivation of vegetables, fruit, honey and similar are activities that do not have continuity throughout the year and did not bring much novelty in the Valtellina area. Then, talking to a friend who is passionate about beer, we started to reflect on this opportunity: an activity linked to products of the land, whose production requires continuity throughout the year (an essential for an educational service), and with a very broad range of activities involved, from simple and repetitive actions to more complex ones, from practical actions to conceptual ones. It seemed to us the solution we were looking for to provide a suitable service to the users we wanted to involve and it proved to be the right choice. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

Beer is synonymous with conviviality, cheerfulness and togetherness. It seemed a suitable starting point for a new, more lively, educational project. Furthermore, the production of beer is simple and its phases can be managed by individuals with different disabilities. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

From the ideation stage to the actual realisation of the social microbrewery, more than a year passed. This was due to both financial and bureaucratic reasons. Financially, the founding members did not have the necessary resources to build the brewing infrastructure. They therefore decided to participate in a call for proposals on social agriculture, which was carried out by the Provaltellina-Onlus Community Foundation and by the Credito Valtellinese Group. The project was evaluated positively and the finance awarded covered 50% of the resources necessary for the realisation of the project. The other half was paid by the Prometeo-Onlus Association, supplemented by donations from local and regional organisations (e.g., BIM—Bacino Imbrifero Montano della Valtellina, Sondrio, and Cariplo Foundation, Milan, Italy). From a bureaucratic point of view, the Prometeo-Onlus Association was not a suitable organisational model for carrying out social and economic activities simultaneously. Therefore, a year later, on 7 March 2014, the cooperative Elianto, a type B social cooperative (i.e., focusing on the work integration of vulnerable people), was established, to directly manage the brewery. Once the cooperative was constituted, the Association Prometeo-Onlus entrusted it with the management of all its activities related to craft beer production. Thanks to the funding received, renovation of the production site was carried out, brewing equipment was purchased and the first beers were brewed and tested. The sale of Pinalpina beers officially commenced in January 2015. Over the years the cooperative has hosted numerous (on average eight per year) young people between 16 and 30, with different types of disabilities. They are engaged through extra-curricular internships and school-work alternation, creating different educational pathways for each person. They are mainly employed in the labelling of beers, boxing and shipping and checking and numbering of production lots, but also in administration, dealing with invoices and managing the telephones. In 2019, the social microbrewery provided opportunities for seven vulnerable people, all with cognitive conditions: four through a scholarship and three through an internship.

Those who come to us do not just spend time, but learn a job, a real job, in spite of what is sometimes thought of social projects. Ours are willing kids and have nothing less than the others. Indeed, they have something more. And what they learn here is on par with what classmates can learn in other businesses. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

As for the sales channels used by the brewery, these initially focused on the direct sale of their beers through an on-site shop. In addition to direct sales, other sales channels include bars, specialist stores stocking bottled beers and public festivals and events within the Valley for the sale of draft beer. In February 2020, the cooperative decided to participate in one of the most important national events dedicated to beer: the ‘Brewer of the Year’ festival, which takes place in Rimini (Emilia–Romagna). On this occasion, Pintalpina showed that it is possible to combine quality and work-integration of vulnerable people by winning second place in the national competition “Beer of the year 2020” Double IPA category, with their ‘Sbrega’ beer. Everything Pintalpina obtains from the sale of beers is reinvested in the cooperative, to allow the continuous development of ideas and job opportunities for people with different abilities.

A moment of incredible satisfaction. Our production is perhaps slower, because it is calibrated to everyone’s needs and abilities, but, in any case, everyone is required to take an active part in the production process, like the many pieces of a puzzle that ultimately make up the original picture, in our case, beer. The commercialisation of beer allows us to be economically independent. This is possible not only thanks to the quality of our product, but also to the cooperative approach of our activity, in which the members make available time, energy and skills, and also to the collaborations activated in the area. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

The scaling strategies implemented by Pintalpina are mainly oriented towards increasing the number of people engaged with its activities (products and services) and achieving a cultural impact on the area where it operates. They include product diversification, network and partnership building and organisational growth.

The first strategy concerns the diversification of the marketed product; beer. Offering an increased variety of beers allows the cooperative to reach a wider clientele. In the first year of activity (2015–16), Pintalpina produced two types of beer: a golden ale and a double IPA. In 2020, the social microbrewery currently produces nine different beers. Six are produced year-round: a Golden Ale, a Double IPA, a wheat beer seasoned with hibiscus flowers and coriander, a Belgian double red, a Saison with rye and a California common. Three beers are seasonal: an Italian Grape Ale, a Blanche with raspberry and a special hoppy Saison produced for the Morborock Festival, which is a free independent rock festival in Morbegno, a municipality in the province of Sondrio.

In the realisation of the brewery project, the role of the master brewer was obviously fundamental and our meeting with him was also something special, a story of friendship and gratuity, in line with the project we are carrying out. Thanks to mutual friends, we met Mattia, a young man passionate about craft beer, who self-produced his beers at home. He was a ‘homebrewer’. We asked him if he wanted to do the same thing inside a real business structure. He accepted and we gave him carte blanche and freedom to experiment with his recipes. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

In addition, diversifying the product portfolio allows a wider promotion of the cultural heritage of Valtellina. To enhance and strengthen the bond with the territory, the cooperative purchases its ingredients from local farmers in Valtellina. Both the beer names and bottle labels are written in Valtellinese dialect. This is a method of storytelling, passing on rural history and promoting the cultural heritage of the community. For example, the rye beer is named ‘Sumartì’ (‘San Martino’ in Italian) after an old saying among farmers, who recommend sowing rye in the autumn, by the day of San Martino (St. Martin’s day falls on the 11th of November), to hope for a good harvest the following summer.

Our territory and its mountains do not just frame our brewery, but they give us many resources that enter the character of all our beers. We always try to combine barley malt with some local products such as rye, purchased from a cooperative in the area that has recovered uncultivated land, or grape must or raspberries, which are produced by two local companies. Companies and people who share with us the love and passion for their work, their products, their territory. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

The second scaling strategy, closely linked to the first, is building local relationship networks and partnerships. On the one hand, developing strong local relationships allows the cooperative to extend its reach and come into contact with a greater number of people. On the other hand, embedding the organisation in the local community allows strengthened ties at the local level, enhancing the community itself while also passing on the mountain farming traditions. The ingredients used in brewing come from the Valtellina area. First of all, pure water, an essential element for brewing good beer. The cooperative sources it from springs in Val Fontana, at over 1,200 meters above sea level. Other local products are sourced in partnership with local companies. For instance, ‘Càles’ beer (Italian Grape Ale—IGA—a specific Italian beer style that uses grape (fresh must or fresh grapes) in the recipe) is produced with the must of Nebbiolo grapes, grown in the Valtellina Superiore DOCG area (DOCG stands for Denominazione di Orgine Controllata e Garantita (Denomination of Controlled and Guaranteed Origin). It is an origin and quality certification—the highest designation of quality—for Italian wines. Valtellina Superiore is a dry Italian red wine. Its production is only allowed in the province of Sondrio (Lombardia region)), in partnership with the Azienda Agricola Folini (Chiuro, Italy), a small local company that produces fine wines. In the valley, the collaborations are extended to small agricultural producers who donate and supply products such as rye (produced with native Valtellina seeds from the Rezia Alpine Biodiversity farm in Teglio, 8 km from the brewery) or the small fruits with which ‘Murimani’ beer is produced, which are grown by the farm Azienda Agricola Patrick Fendoni.

The third scaling strategy concerns organisational growth. On the one hand, organisational growth allows the cooperative to increase the number of customers and vulnerable people included in the brewery’s activities. On the other hand, an increase in turnover allows a strengthening of the autonomy of the brewery and an increase in the stability of the jobs offered to the vulnerable. In the first months of 2019, after having taken root in the Valtellinese territory and the neighboring areas, the social brewery began to take its first steps beyond its borders, to promote Pintalpina and its beers nationally. To do this, the brewery started a progressive restructuring of the brewery, which will bring the cooperative, by the end of 2020, to a significant expansion of production and distribution. At the beginning of 2020, the main investments concerned the purchase of isobaric bottling equipment, the refurbishment of the flooring and workspaces, the renovation of the on-site shop and the installation of new 1000 litre capacity production facilities. As highlighted by the cooperative director during the interview, in the first 3 years of activity, 95% of beer sales were within the province of Sondrio. At the beginning of 2020, sales growth outside of the province has increased to a point where local consumption represents 85% of overall production, with regional (13%) and national (2%) sales having increased significantly despite the latter being only recently introduced. Regional and national sales are managed externally through an online shop (‘Valtellina Shop’), which sells a range of products typical of Valtellina. Selling products nationally is an important strategy to increase the volume of sales and therefore the turnover, and subsequently increase opportunities for work integration of vulnerable people. In other words, organisational growth is considered a significant, but not fundamental, goal for the cooperative.

Our goal always remains the well-being of those we integrate in the workplace. We do not want to become a big brewery, involving 30 or more vulnerable people. The size of the microbrewery is perfect as long as we can do our job well. We want to proceed with caution, step by step. However, increasing sales is important to be independent from a financial point of view and to be an example for those who are interested in this approach and want to invest in this sector. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

The next step will be the creation, by summer 2020, of an outdoor taproom, to welcome visitors, the organisation of tasting events, and the strengthening of the relationship between the brewery and its customers.

4.2. Articioc

Articioc is a type B social cooperative (i.e., focusing on the work integration of vulnerable people). Its mission is to combine beer production with the social and work integration of people with physical disabilities and mental health conditions. Articioc was constituted in 2014. Its founding members were a group of friends, passionate about beer, who, ten years before, had founded a cultural association, named ‘Altafermentazione’, to promote craft beer production and consumption in the territory of Parma (Emilia–Romagna region). Altafermentazione was one of the first associations to join Unionbirrai, the national association that enabled the development of the craft beer movement in Italy.

Altafermentazione was constituted at a time when the craft beer movement was still in its infancy in Italy, [...] with the aim of promoting the culture of craft beer. Our activity consisted of organising tasting evenings and events (when possible with producers) to make this new product known and to highlight the differences between craft and industrial beer production. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

All proceeds from the activities of Altafermentazione were donated to other associations and cooperatives operating in the social sector. Among these, a type A social cooperative (i.e., focusing on socio-healthcare and educational services delivery) linked to the sports sector and, in particular, to the Special Olympics games, an international sporting competition for athletes with physical and mental disabilities.

We had an excellent relationship with the elderly president of the cooperative. In our many conversations he often complained that he had been unable to do anything to offer job opportunities to the young men he worked with. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

In 2009, these conversations led to a meeting between the members of Altafermentazione and representatives of the Special Olympics, during which the idea of combining craft beer production and the delivery of social services started developing. The shared focus was the creation of job opportunities for people with disabilities. In 2014, the social cooperative Articioc was constituted, with the aim of opening a social microbrewery. It was officially set up in 2017, with the inauguration of a new production plant, and brewing started in 2018. By early 2020, the social microbrewery employs two people with a permanent contract: an activity coordinator and a disabled employee, involved in production and sales activities. In addition, a volunteer and member of the cooperative operate as a sales manager and other vulnerable individuals are involved in the brewery’s activities through job placement and internship programmes. One of these is funded by the municipality of Parma, targeted at a disabled individual and aimed at later employing that trainee. Another placement is carried out in collaboration with another social cooperative, targeted at four asylum seekers and aimed at teaching beer brewing techniques. The long-term goal is to employ at least one of them in the production laboratory and for logistics activities. The cooperative is also looking for vulnerable people to employ in the taproom, its latest project, to work with the public and interact with customers. Direct selling is the most important sales channel and the majority of trade occurs at an on-site shop. In addition, the cooperative is planning to open a taproom, offering draft beer, and a pub, in collaboration with other local organisations. The cooperative’s commercial strategy is mainly focused at a local and regional level and especially on the two provinces of Parma and Piacenza. For the sale of products in other provinces, such as those of Reggio Emilia, Mantua and Cremona, the cooperative relies on distributors. In the near future, the goal is to cover the whole Emilia–Romagna region, Lombardy up to Milan and the area around Venice.

The key scaling strategy implemented by Articioc is network and partnership building, which is mainly oriented towards generating an impact on greater numbers (e.g., increasing the number of stakeholders involved in the project and benefitting from its activities) and on cultural roots (e.g., changing the way social cooperation is perceived by the general public). This emerges at every stage of the development of their social microbrewery.

Before Articioc was constituted, the founding members’ participation in local networks in the field of craft beer production (through the association Altafermentazione) enabled the creation of the cooperative. Participation in these networks not only built the capabilities of the founders (e.g., in craft beer production and events organisation) and their relationships (e.g., with craft beer producers, other associations, social cooperatives, pubs, retailers, etc.), but they also broadened their horizons: boosting their creativity and imagining the possibility of creating a social microbrewery.

In Italy, projects similar to ours were born, such as that of Vecchia Orsa in San Giovanni in Persiceto (Bologna), Pausa Caffè in Saluzzo (Turin) and, almost, at the same time as ours, the Vale la Pena project in Rome. These projects made us realise that it was possible to do it and so we decided to ‘throw our hearts over the obstacle’ and create a social cooperative. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

In the start-up phase, partnerships allowed Articioc to start producing even before having their own production site. Between 2014 and 2017, Articioc operated as a beer firm, producing their beers at partner breweries.

The project did not start immediately, because we did not have the economic resources to get it started. [...] At the beginning we did not yet have the resources to invest in our own production plants, but we had the skills and we knew many craft breweries, so we decided to start as a beer firm. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

The beer firm model concerns brewers who do not own their own production facility, but create their beers using those of other producers. This category is further divided: those who actively follow each phase of the beer creation and those who totally delegate the production, simply sticking their own brand on the finished product. Articioc, in its first phase of development, belonged to the first category. The members of the cooperative developed the recipes themselves and used the host’s facilities to brew their own beers. The advantages of the beer firm model are varied. First of all, it requires low levels of investment. As a beer firm, Articioc entered the craft beer market without having to face high purchasing and running costs. Secondly, producing at other plants allowed the members to gain experience, to test some beers and to evaluate which ones were most successful on the market.

It was our only choice. It allowed us to produce at lower costs, acquire considerable experience and come into contact with experts in the sector. We started with the production of only one beer. Then, after a while, we moved up to three. We went to sell it with our gazebo at local events in the villages near our headquarters. In these events, two young men with disabilities also came to work with us, thanks also to a collaboration with the cooperative La Bula di Parma. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

The beer firm model also has limitations, such as the higher price of beer for the market, which leads to lower profit margins. In addition, producing at other breweries’ facilities requires the brewer to adapt to the production capacity and characteristics of the host plant. It also limits the opportunities for work integration of vulnerable people, which was at the heart of Articioc’s constitution. During the first three years of activity, thanks to the strength of its social relationship with local stakeholders, the cooperative was able to acquire the economic assets necessary to purchase its own beer production plant. In other words, the participation in networks and the constitution of partnerships have enabled the cooperative’s organisational growth.

Initially, the most demanding activity was that of direct sales at fairs and farmers markets in the summer season [...]. Participation in fairs and markets has allowed the creation and development of a collaborative social network, essential for the launch of our project. The network was formed almost naturally, sharing experiences, dreams and hopes, first over a pint and then with increasingly assiduous and continuous meetings as it was understood that important synergies and collaborations could be created. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

To share knowledge and experiences, to grow together with other cooperatives and associations and to always keep in mind a vision oriented towards the common good: these were the pillars on which Articioc was founded. The strategy of building networks and partnerships has allowed the cooperative to establish ever closer collaborations with numerous stakeholders, including the association ‘Sanseverina’, the social cooperatives ‘Insieme’ and ‘Il Cigno Verde’, the cooperative ‘La Bula’ and the social solidarity consortium ‘Confcooperative’. Together as a network, they submitted a project proposal to a call by the foundation ‘Cariparma’. In 2016, they were awarded by ‘Cariparma’ the funding necessary to build Articioc’s social microbrewery. The aim of the project was to link local actors to build a short supply chain in the craft beer sector, from the cultivation of raw materials to catering, keeping at the centre the inclusion of vulnerable people.

In the consolidation phase, partnerships allowed Articioc to acquire and exchange skills and abilities—as well as to share business risk—with other organisations. In other words, after 2017, the construction of new networks and partnerships allowed the cooperative to broaden their scope of action and extend their reach, while also to cross-pollinate (i.e., influence and be influenced by) the craft beer sector and social cooperation practices.

In the cooperative world there are no ‘owners’ and ‘employees’, but cooperators who, by sharing the same mission, work for the common good. Precisely for this reason, cooperatives are often in solidarity with each other and find synergies and collaborations that are useful for the whole community. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

In this phase, two cooperatives became members of Articioc. They are the social cooperative ‘Insieme’ (type A), which provides semi-residential and residential socio-rehabilitation services for young people and adults with disabilities, and the social cooperative ‘Il Cigno Verde’ (type B), which specialises in the job placement of vulnerable people in activities related to the environment. These two cooperatives provided the know-how and skills in the work integration of people with disabilities and the connection with the territorial services designated for their social care. As a relatively young cooperative, Articioc learned immensely from them. At the same time, Articioc represented a stimulus for them, meeting their need for social innovation. In a historical context in which public resources were decreasing markedly, it became essential to activate new initiatives capable of attracting resources from the market.

The exchange of skills is mutual. The Cigno Verde cooperative, for example, is also starting to think about its evolution and together we are thinking of taking over a bar (which today sells our beers) [...] to manage it together. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

Finally, in the promotion and development phase of the cooperative, the formation of new relationship networks and partnerships has allowed Articioc to further increase the number of people and organisations impacted by its activities while also strengthening its social mission and fostering cultural change. In September 2019, Articioc signed a collaboration agreement with ‘Agrinascente - Parma2064’, a renowned dairy cooperative. Together, they designed specific beers to match with Parmesan cheese, with the aim of enhancing the marketing of each other’s products and promotion of their social initiatives.

We have started testing a beer made with malvasia must to be combined with a type of Parmigiano Reggiano. We will present it at international events, in cities such as New York. Beer can be an excellent way to promote other products related to the tradition of our lands, such as Parmesan cheese. More generally, the collaboration will also be oriented towards raising awareness around the values of social cooperation. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

In December 2019, the cooperative started a further collaboration, with the association ‘CIAC’, which combines social agriculture with the reception and social integration of migrants and asylum seekers. CIAC joined Articioc as a member. Their collaboration is based around the procurement of raw materials (local and organic ingredients) by CIAC for the production of Articioc beers. At the beginning of 2020, the cooperative plans to open its own pub, again in collaboration with other cooperatives, in the centre of Parma. This will be a space for the commercialisation and consumption of Articioc beers and of local products by other cooperatives. It will also include a restaurant service. This will not only allow further organisational growth, thereby increasing the volume of production and the cooperative’s capability to stay on the market, but it may also enable a deeper cultural impact.

During the first years of our activity, at many of the beer festivals we have been to, especially outside the region, in territories where social cooperation is perhaps not so strong, many consumers, when they read the words ‘social cooperative’, looked at us strangely, with diffidence, because they basically did not understand what we were doing. Nowadays, thanks to our work and that of others engaged in the same sector and with the same values, the perception is changing. Certainly, as regards the field of disabilities, the road is still long [...] and the production of craft beer can be an excellent means to increase the visibility of the social sector and to generate greater social impact. (Interview with the director of the cooperative)

4.3. Vecchia Orsa

The social microbrewery Vecchia Orsa was constituted in 2007, in Crevalcore (Bologna), as a project of the social cooperative ‘FattoriAbilità’, which was founded in 2006 to integrate people with disabilities into the job market. The cooperative was created to manage an educational farm, linked to donkey-assisted therapy (an alternative or complementary type of therapy that involves donkeys as a form of treatment that can help to develop the social and emotional skill set of patients). Although the educational farm was well-established and managed in collaboration with other social organisations (in particular with a social cooperative that ran a day care centre for the disabled), the project was unable to get off the ground. The idea of making use of the spaces available to the cooperative to combine craft beer production and work integration originated from the meeting of FattoriAbilità members with two home brewing experts, one of whom was also an educator. Together, they founded the microbrewery Vecchia Orsa, which, under the guidance of the master brewers, started producing the first craft beers in 2008. The project, committed to create training and job opportunities for vulnerable people, quickly became the main activity of the cooperative FattoriAbilità.

Our slogan is ‘the social aftertaste of beer’, which expresses the balance between economic (beer production) and social activities (attention to people and their different abilities). (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

In the first five years of activity, the brewery was a huge success, with a constantly increasing production volume, which quadrupled in the first three years. The first production plant (with a capacity of about 70 litres per brewing cycle) was thus expanded in 2010 (to 200 litres per cycle). However, this momentum soon suffered a significant setback. In May 2012, the tragic earthquake that hit Emilia–Romagna made the brewery headquarters and warehouse unusable. After the earthquake, the cooperative was forced to move its production plant to San Giovanni in Persiceto, which is a small rural municipality 10 km from Crevalcore, located nearby the Metropolitan City of Bologna, bordering with the two provinces of Modena and Ferrara. The new headquarters had already been identified for a future shift due to the expansion of production, but in 2012 it was not yet ready to use. The inconvenience could have been very serious had it not been for the solidarity shown to the cooperative, primarily from the brewing world.

We were lucky, because many helped us. Somebody offered us a refrigerated warehouse where we could put the brewed beers, somebody else pledged to buy kegs and bottles. Others sent beer for free to sell for fundraising. We were also lucky enough to collaborate with some breweries such as Amarcord and Brewfist, and we could continue selling through that channel without interruptions. At that time, our blonde beer was renamed for the occasion as ‘Magnitude Blonde’. This is a good story that has shown us how solidarity is fundamental at certain times. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

The new headquarters of the social brewery were inaugurated in April 2013. This was an opportunity for Vecchia Orsa to grow, expanding production volume, number of beers produced and number of work placements, this being the real objective of the project. The increase in work placements was also due to the choice not to automate the production process and to the start of new collaborations, aimed at creating training courses, internships and job grants with some local organisations (among which, the foundation ‘Fomal’ and the school ‘Archimede’ of San Giovanni in Persiceto). The vulnerable people employed by the cooperative are engaged in different activities: from the different stages of the production process to bottling, from labelling and boxing up to sales. Work placements are implemented progressively. Step by step, young people with disabilities can learn work routines and participate actively in every stage of the production and commercialisation processes. Among those employed, two people have worked inside the brewery since the beginning, first with a job grant and today employed part-time on a permanent basis. In relation to sales channels, Vecchia Orsa combines direct selling (e.g., on-site shop) with online distribution (e.g., thanks to the collaboration with ‘Local to you’, an e-commerce platform that promotes local and organic agriculture).

In terms of scaling, Vecchia Orsa focuses on organisational growth as a means to achieve a higher number of work-integrations and to strengthen the culture of social solidarity. In Vecchia Orsa, organisational growth is enabled by the very high quality of raw materials used for brewing, product and service diversification, and partnership building (including business acquisition).

First of all, it should be noted that organisational growth for Vecchia Orsa is not an end in itself, but always instrumental to the creation of social and environmental value.

We are a social cooperative and our goal is to pay attention to the people with whom we have chosen to work. We start from the person and not from the product. This is why we try to make all stages of production, bottling, labelling etc. as manual as possible, just to enhance the different skills of each. Each bottle is handled by our team at least six-seven times. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

Our commitment lies more in the word ‘artisan’ rather than in the word ‘beer’. Our strength lies in the establishment of mixed groups where all workers, ‘able’ and ‘disabled’, operate with equal dignity and a sense of belonging. But then it is beer that we have to sell and being innovative is fundamental. (Interview with a member of the cooperative)

For example, Vecchia Orsa has chosen to produce only high fermentation beers, because this production method involves a further phase in the production process (refermentation). In this way, it is possible to have a larger work team. In the philosophy of the social brewery, attention to social issues (work integration of vulnerable people) is combined with attention to the environment. For example, Vecchia Orsa experiments with circular economy practices (as described below) and supplies the production plant with electricity from renewable sources.

The first strategy that makes the brewery competitive on the market and allows organisational growth is the use of high quality raw materials. This translates into the production of 12 excellent quality beers, recognised by high-profile awards in the Italian restaurant industry. They are: a fruit blanche, an organic golden ale, a blonde (2nd classified Beer of the Year 2010 and 3rd classified Beer of the Year 2014, golden ale category), a Saison (1st classified Beer with spices of the year 2012), a Belgian Ale, an IPA (Slow Food Daily Beer 2015), a Black soul IPA (Large Slow Food Beer 2017 and 2nd classified Beer of the Year 2020, ipa category), an Imperial Russian Stout (Slow Food Daily Beer 2015), an amber ale, a Tripel, a Weisse beer, and a Saison IPA.

The second strategy is diversification, both of the product and of the service offered. The beers produced are inspired by various brewing styles, such as those from Belgium, Germany, the United Kingdom and the USA. In addition to beers, the social microbrewery also produces ‘beer jellies’ in three flavours, to be enjoyed with cheese and meat.

Who more than us can be in favour of diversity!? Just as for us, it is fundamental to enhance the diversity between people, the same applies to the beers produced. And this also has a return in terms of sales. Greater diversity means more customers with different tastes. (Interview with a member of the cooperative).

Among the beers produced, one is certified organic and the first organic beer in Emilia–Romagna. It was produced as a result of the relationship between Vecchia Orsa, the pub ‘Harvest’ and the restaurant/pizzeria/shop ‘Alce Nero-Berberé’ in Bologna. As for the diversification of the service offered, the new location includes a taproom, a shop and a brewpub. In the latter, beers (eight draft beers in addition to the bottled ones) are sold and accompanied by other local products, including ‘piadina’ and ‘tigelle’ (two types of typical Italian bread, prepared in the Emilia–Romagna region) mixed with must and ‘spent grains’ (the main by-product of the brewing process). This initiative is carried out following a circular economy logic, in collaboration with the bakers of San Giovanni in Persiceto. The same collaboration, supported by business confederations such as the Bakers Association of Bologna and the Confcommercio Ascom of Bologna, is also working towards the production of a beer named ‘Fornara’, a Golden Ale brewed—as well as with the usual ingredients—with stale bread unsold by local bakers.

The third strategy, closely linked to the first two, is the development of partnerships. This includes less formal collaborations, oriented towards knowledge and skill sharing, and stronger ties, leading to business acquisition. In June 2018, the social cooperative Fattoriabilità (then owner of the social brewery) started collaborating with the social cooperative Arca di Noè, which is a type B + A cooperative, operating in Bologna and committed to the social and work integration of vulnerable people, with a particular focus on asylum seekers and migrants. The idea was for the two cooperatives to join forces and try to grow together, sharing the same social culture, values and objectives. This collaboration led to a further growth of Vecchia Orsa, making the social brewery become a reference point for an increasing number of people from Bologna and neighbouring areas. In June 2019, in addition to the brewpub in San Giovanni in Persiceto, which was already very popular among craft beer lovers, the restaurant ’Fuori Orsa’ was inaugurated. This restaurant is a seasonal (summer) activity, located in the centre of Bologna inside of the Dopolavoro Ferroviario park and next to an open-air cinema. Since 2019, the restaurant ’Fuori Orsa’ has included a bar and space for cultural events, managed jointly by the two cooperatives. Within the restaurant, young disabled people employed by the brewery and young migrants employed by Arca di Noè work side by side in a joint activity. Thanks to the fruitful collaboration started in 2019, Vecchia Orsa has identified an important opportunity to strengthen and expand its business. At the same time, Arca di Noè has found an opportunity to scale through a strategy of diversification and expansion of the work placement activities of vulnerable people. In January 2020, the social microbrewery Vecchia Orsa (until then managed by the social cooperative Fattoriabilità) was acquired by the social cooperative Arca di Noè. In this way, through a horizontal integration strategy with a large cooperative, Vecchia Orsa can continue to pursue its objectives, optimise its job placement activities and open up to a new commercial phase of promotion and sale of their beers.

Our beer is a recognised product of great quality, but above all, it is a means of conveying the values of the project and its social mission. Today this objective can be pursued with greater strength and we are particularly proud of this. (Interview with a member of the cooperative).

5. Discussion

Cross-case analysis has provided three main points for discussion. First, the craft beer sector represents an opportunity for innovation in social agriculture—and particularly for the work integration of vulnerable people. As it emerges from the three social microbreweries analysed in this research, the production of craft beer is ideally suited to the therapeutic needs, training and work-integration of vulnerable people in many ways. In the craft beer production process, each phase is distinct (e.g., malt grinding, cooking, flavouring, fermentation, bottling, capping, labelling and boxing). That is, a step-by-step process, which allows the integration of disadvantaged workers with different skills, offering each one a task, and therefore a role, with which to familiarise themselves, improve and succeed. Moreover, craft beer production includes working routines that require manual skills as well as creativity, facilitating the establishment of a collaborative and artisanal learning environment. The combination of these factors ensures personal gratification while increasing the degree of social and work integration of people with physical or mental impairment. Craft beer production is also an important opportunity for social cooperatives to diversify their activity portfolio and to increase their financial stability (i.e., decreasing their dependency on depleted public funds). While the main source of revenue for social cooperatives is the sale of goods and services to public entities (type A cooperatives in particular, focusing on socio-healthcare and educational services delivery) [64], they also operate on the open market (type B cooperatives in particular, focusing on the work integration of vulnerable people). Craft beer is a growing industry [65] that can provide a stable revenue stream and improve the economic performance of social cooperatives. More broadly, social microbreweries can have a positive effect on rural development—i.e., boosting economic, social, cultural and agricultural activities in rural areas through the production and commercialisation of craft beer. The cultivation of key ingredients, such as barley, malt and hops in particular, allows the rediscovering of traditional products, typical of the locale (e.g., rye in the case of Pintalpina). Valuing local resources (both tangible, such as agricultural products, and intangible, such as knowledge, languages, production techniques, etc.) also provides market opportunities. Indeed, highlighting the link between the local area and the product can give beers a local identity, making them more competitive on the national market [20,23,27,30,66]. Tourism benefits from this too, craft beer tourism being an emerging and booming sector [32,33,34,35,36,37]. The multifunctionality intrinsic in the craft beer sector represents a fertile ground for the development of social agriculture initiatives, pursuing therapeutic, educational and work integration goals through the production of raw materials for the brewing process.

Second, scaling social microbreweries involves a variety of scaling approaches, including: organisational growth, scaling out and scaling deep. Insights from the case of Vecchia Orsa show that organisational growth is a key approach to increase social impact. This is what Bauwens et al. [54] describe as ‘breadth scaling’, Lyon and Fernandez [67] call ‘business growth’ and several other authors define in terms of ‘scaling up’ [55,58,59]. Organisational growth is typically the scaling strategy adopted by for-profit enterprises, with the purpose of maximising the shareholders’ return on investment. In the context of social cooperatives, where profit is a means to achieve a social mission, organisational growth is not an end in itself. Indeed, the case of Vecchia Orsa shows that this approach is adopted to ultimately enable the microbrewery to provide new opportunities for work integration and to strengthen the culture of social cooperation in the craft beer sector. Riddell and Moore [60] classify this as ‘scaling out’ (impacting greater numbers) and ‘scaling deep’ (impacting cultural roots), respectively. In other words, organisational growth in Vecchia Orsa is oriented towards creating social value, thereby fulfilling the organisational mission. The close connection between scaling and organisational mission was also observed by Smith and Stevens [68] in the context of social enterprises.

The analysis of Pintalpina and Articioc shows that scaling out and scaling deep are key approaches to scaling social impact. Scaling out is defined by Riddell and Moore [60] as impacting greater numbers. This research shows that scaling out in social microbreweries is related to an increase in (i) work integrations within the organisation; (ii) customer base; (iii) other stakeholders engaged with its social mission. For the first, as already demonstrated by the case of Vecchia Orsa, increasing the number of work-integrations within the brewery is closely linked to organisational growth processes (i.e., the bigger the business, the more people can be employed). For the second, increasing the customer base is closely linked to strategies of product and service diversification. As the findings show, Pintalpina and Vecchia Orsa have already embarked on product diversification, while Articioc, being a relatively new brewery, offers a limited range of beers. Regarding service diversification, the three breweries focus on craft beer production and commercialisation, although that is marketed through different channels—the minimum common denominator being an on-site shop, a tap room and direct selling at local festivals and events. For the third, growing stakeholder and community engagement is closely linked to strategies of network and partnership building. While Vecchia Orsa has invested in breadth scaling, Pintalpina and Articioc are less interested in a growth in size and more focused on developing community-based initiatives. A higher degree of embeddedness in the local community facilitates cooperation with stakeholders [69,70,71].

Scaling deep is defined by Riddell and Moore [61] as impacting cultural roots. The cultural impact generated by craft beer production and consumption is related to (i) employees; (ii) consumers; (iii) other stakeholders, including the wider community. For the first, from an employee’s point of view, scaling deep is mainly related to the educational and training courses offered by the brewery to its workers. For example, in Pintalpina, the master brewer is supported by two professional educators, with the aim of developing individualised educational and training paths, in line with the cognitive and psychophysical abilities of each worker. According to the cooperative’s philosophy, work integration and education are two closely related practices. What matters is not only developing skills to be able to perform practical tasks but, above all, ‘learning to work’—i.e., to be independent and take responsibility.

For the second, from a consumer’s point of view, scaling deep is mainly related to changing the perception towards social cooperation. As the case of Articioc shows, the direct interaction between customers and vulnerable employees has increased mutual trust and allowed social cooperation to be perceived as a business, rather than a philanthropic activity. The acknowledgment of the vulnerable members’ active role, in each stage of the brewing process, grants dignity and recognition to their work. For the third, from the point of view of other stakeholders (e.g., partner organisations and the wider community), scaling deep is mainly linked to the objective of spreading a new culture of production and consumption, based on quality products, social solidarity and the appreciation of local cultural heritage. In strengthening this socio-cultural transformation, the dissemination of knowledge, skills and values plays an essential role.

Beside scaling out and scaling deep, Riddell and Moore [60] identify another approach to scaling social impact, named ‘scaling up’. This is not related to organisational growth, as the name may mistakenly suggest, but on impacting laws and policies. This scaling approach does not emerge in any of the cases analysed. This could be due to a lower degree of involvement with public authorities, in comparison to other social cooperatives (e.g., in public sector procurement) and/or to a low degree of participation in public decision making, which in turn can feed the perception of not being able to influence laws and policies.

Third, network and partnership building is a key scaling strategy in each of the social microbreweries analysed (i.e., essential for pursuing organisational growth as well as for scaling out and scaling deep). Different kinds of networks are built in different contexts, in which the background of the founders plays an important role [39]. For example, in Pintalpina, the majority of members have a background in education and a lack of expertise in agriculture. Because of this, the brewery has established networks predominantly with farmers and other stakeholders involved in the agricultural world. The participation in these networks allowed the brewery to acquire information, skills and raw materials that are typical of the locale and high quality. On the other hand, in Articioc, the founders had a strong background in craft beer production and a lack of expertise in the social sector. Therefore, they built relationships with a wide range of social enterprises, learning about the process of work integration. Networking strengthens trust and cooperative behaviour among local stakeholders and it is often the first step towards the constitution of partnerships.

Different types of partnerships require different levels of involvement—from informal collaborations to stronger ties. Pintalpina and Articioc both adopted a strategy of ‘affiliation’ [71]. However, while Pintalpina built informal collaborations and partnerships with external organisations based on low involvement and great autonomy of stakeholders (mainly suppliers), Articioc built strong ties with stakeholders who later became members of the social cooperative or partners for specific projects. Vecchia Orsa has effectively adopted a strategy of ‘branching’ [71]. When acquired by the cooperative Arca di Noè, it maintained its own product site, brand and autonomy and opened up to a new territory (the city of Bologna). Overall, partnership building in the context of social microbreweries is not aimed at business replication (e.g., geographical scalability through franchising), but at enhancing the social impact of their activities on their beneficiaries and community [72]. The three cases analysed in this research show that it is possible to build positive interactions with different local stakeholders (both social enterprises and for profit organisations), based on synergies, shared values and interests, rather than on competitive behaviours. In line with other research on social enterprise [73,74], these networks and partnerships represent an important opportunity for social microbreweries to stay on the market and to offer new solutions and services for the local needs of rural communities.

6. Conclusions

This paper has explored the relationship between social agriculture and microbreweries, linking craft beer production and social agricultural cooperation. The craft beer sector emerges from this analysis as providing important opportunities for social innovation in social cooperatives, with a particular focus on the work integration of vulnerable people. This paper has also highlighted different pathways for scaling social microbreweries. To increase the impact of their activities, social microbreweries focus on organisational growth (growing the size of the business), scaling out (impacting greater numbers) and scaling deep (impacting cultural roots). These scaling approaches are pursued in practice through the implementation of different strategies, which vary according to the local context, the background of the founders and the specific characteristics of each brewery. Nonetheless, network and partnership building emerges as a key strategy in each of the social microbreweries analysed. Informal and formal collaborations contribute to the dissemination of essential knowledge, skills, information and practices that distinguish the organisational model of the social microbrewery.