1. Introduction

Chinese Public Rental Housing (PRH), implemented in 2010 [

1], has boomed in recent years [

2]. In 2014 and 2015, the central and local governments invested more than CNY 300 billion in PRH provision [

3,

4]. In 2017 alone, more than 815,600 units of PRH were built [

5]. By the end of 2018, more than 37 million tenants lived in PRH [

6], accounting for about 2.64% of the total population. PRH, as the main project-based rental housing assistance project, meets the housing demands of low- and moderate-income households [

7]. The fast development of PRH is also accompanied by some debate. Some suggest this rapid expansion is a “big leap”—too ambitious and impractical [

7,

8].

A large provision of PRH within a short period poses challenges for the follow-up management [

9]. In the Chinese context, the provision and allocation of PRH often have a one-off feature, while the public rental housing management (PRHM) has repetitive characteristics. Thus, PRHM, in a narrow sense, mainly refers to a series of activities after delivery of PRH, such as rent collection, physical maintenance, tenant management and so on, but not including the provision and allocation process [

10]. Along with the ingrained shortcomings in the provision and allocation process, such as poor building quality and poverty concentration [

11], there are burgeoning criticisms of PRHM, such as unprofessional and inefficient management [

12], overcharged property management fee [

13], illegal subletting [

14], low residents’ satisfaction [

15] and so on. To date, PRHM is far from mature in China [

14].

The difficulties in managing the public rental sector are not unique to China. In many Western countries, early constructed public housing (PH), such as the Pruit-Igoe community in the USA and the Quarry Hill Flats in the UK, encountered many shocking problems shortly after they were delivered [

16]. Since the late 1960s and early 1970s, dissatisfaction with PH has increased in Western countries [

17]. PH has been plagued by many problems, such as high crime rates [

18], high rent arrear rates and so on [

19]. Some studies suggest efficient housing management could resolve such problems and rescue the whole estate from demolition [

20,

21,

22]. From the 1970s, affected by tight budgets and New Public Management theory, the management of the public rental sector in Western countries has undergone a transition [

23,

24]. Some Western countries (regions) have initiated new management programs in the PH sector (

Section 3). Some new policy tools, such as externalization, marketization and privatization [

25,

26], were adopted to improve the management of PH. Instead of direct government intervention in the management of PH, there are other agencies actively involved [

24,

26].

There is an ongoing effort in China to explore the better management of PRH. From 2015, the Ministry of Housing and Urban‒Rural Development (MOHURD) began to motivate nonpublic funds (this mainly refers to funds from private enterprises and non-governmental organizations) to the construction and management of PRH [

27]. However, in former schemes, the main focus of marketization and privatization was to increase provision to PRH. Therefore, there are still many unsolved management problems, such as how to maintain the affordability of PRH, what kinds of services the external participants can provide and so on (see

Section 4). In response to increasingly serious management problems and to provide guidance on local practices, a new scheme was proposed.

In October 2018, the MOHURD and Ministry of Finance (MOF) jointly announced the implementation of a pilot program for the government to procure public rental housing management services. This scheme will be carried out in eight provinces. The new policy has introduced specific measures on the method of selecting external participants, financial arrangements and service contents. It is expected to improve management professionalism and residents’ satisfaction [

28].

Our research question is whether this scheme can solve the former management problems and achieve the reform objectives, so as to explore whether the new scheme can really improve the PRHM. To answer this question, firstly, we collected the policies of several cities in China and summarized several typical management models before the new scheme (

Section 4). Then, we analyzed the new policy, contracts and bidding documents of 19 pilot projects and interviewed some implementation staff. The contribution of this paper is two-fold. (1) It provides a comprehensive and critical assessment of former overdiversified PRHM models in China. (2) It reviews the new policy and its local implementation, possible outcomes and implications.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section introduces basic information about PRHM in China.

Section 3 presents three typical management reform programs in other countries (region).

Section 4 explores the former management models and problems concerning PRHM.

Section 5 proposes the main measures and obstacles of the new policy.

Section 6 demonstrates how the new policy is implemented in a pilot by local housing authorities (LHA).

Section 7 presents a discussion, followed by a summary.

4. Former Management Models and Problems in China

Since China is a large country with significant regional differences, the amount of PRH varies from place to place. The difficulties of PRHM are partly related to the number of PRH. As mentioned above, the management is mainly regulated by the LHA, and is also affected by the economic capacity of the three participants. In this section, we categorize several management models that were employed before the new scheme and summarize the main problems of each.

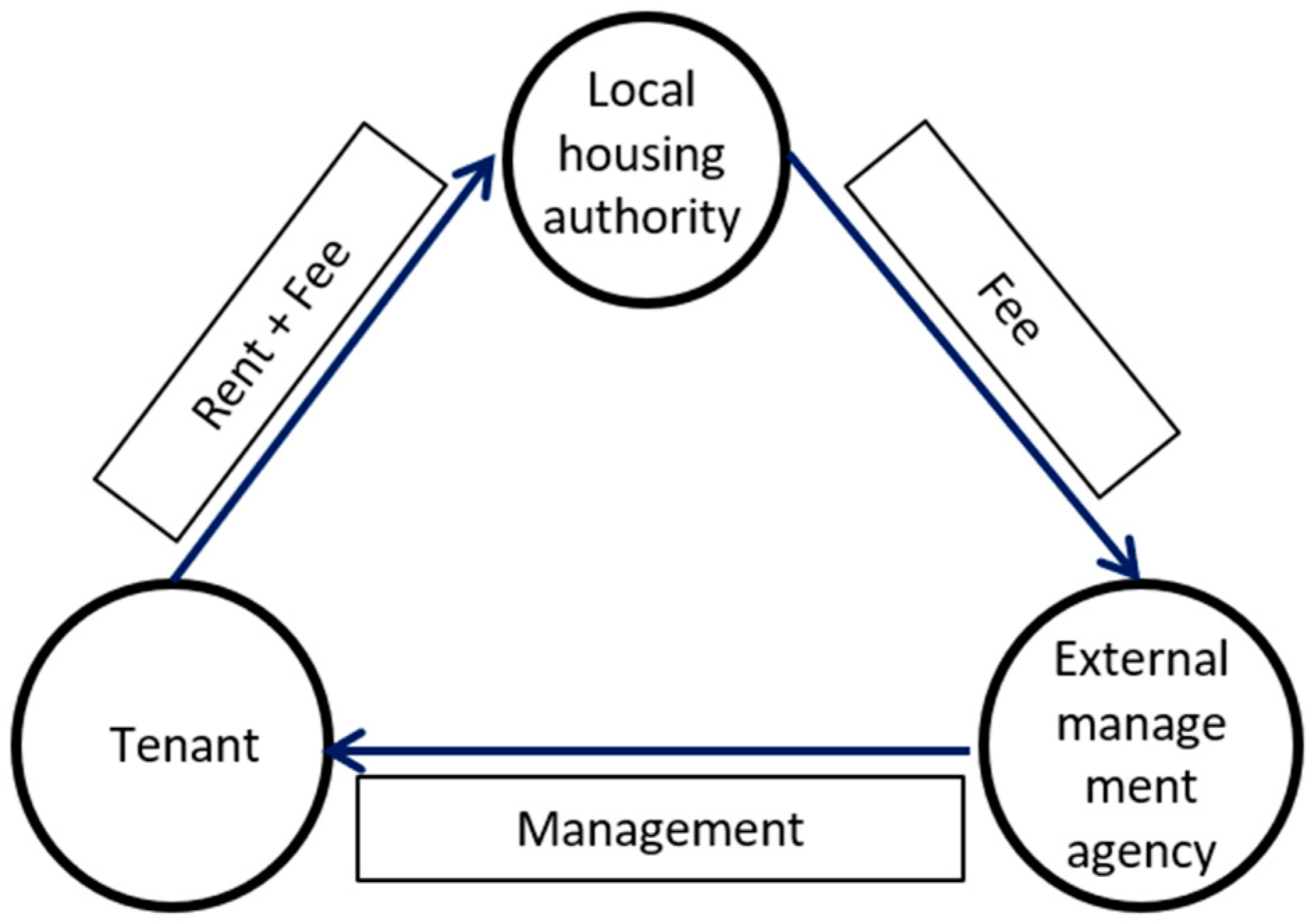

4.1. Government-Led Model

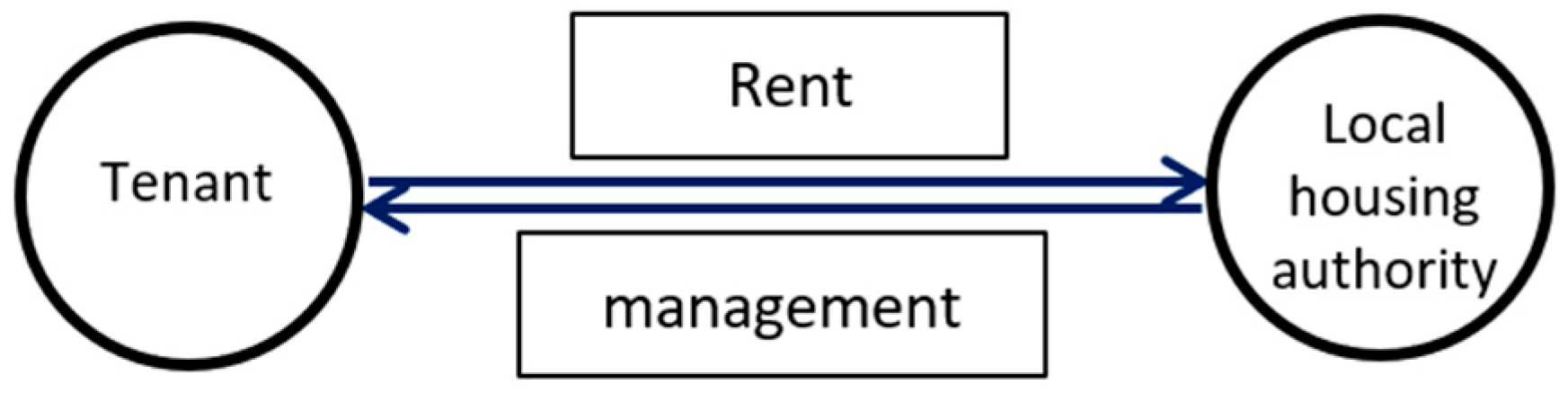

When the stock of PRH was small, the LHA was directly responsible for PRHM. In this government-led model, the tenant paid the rent to the LHA. Meanwhile, the LHA staff addressed specific and detailed management problems, such as avoiding rent arrears, mediating neighbor disputes, and so on (

Figure 1).

In the Chinese context, since it is difficult for government staff to be expelled once they are hired, in order to control the expenditure on personnel, the number of staff from the LHA was basically constant regardless of how many dwellings of PRH were newly delivered to tenants each year. Therefore, as more and more PRH was delivered, the ratio of direct “managers” to tenants became increasingly smaller. The attention and help that the tenants could get was also reduced. Moreover, most of the staff from the LHA were from the planning and construction fields, not the social service field. These limited “managers” not only lacked sufficient time to perform routine maintenance, but also lacked the skills to handle community disputes and rent arrears. Thus, with the rapid expansion of PRH, this model became hard to sustain. Except for in a few places with a small stock of PRH, this government-led model has been gradually fading-away.

The number of staff from the LHA is basically constant and limited and they had to cope with other administrative issues. The time and energy they can invest in the daily management of PRH is insufficient. Hence, this model basically existed in the early stage when the stock of PRH was not large. With the stock expansion, it was difficult for the LHA to intervene in daily and specific management. More external agencies became actively involved in PRHM. Since then, the number of management participants has increased, and the relationships and responsibilities have become more complex. Complicating the questions of which services can be provided by the EMA and how to arrange or share the management fee, several management models coexisted in different places.

4.2. Government-Paid Management Fee Model

Faced with great diverse international precedents (

Section 3), Chinese LHAs chose to start with the most basic and core service. The earliest and most frequently outsourced management service in Chinese PRH is property management, especially for repair and maintenance in shared areas of PRH [

10,

12].

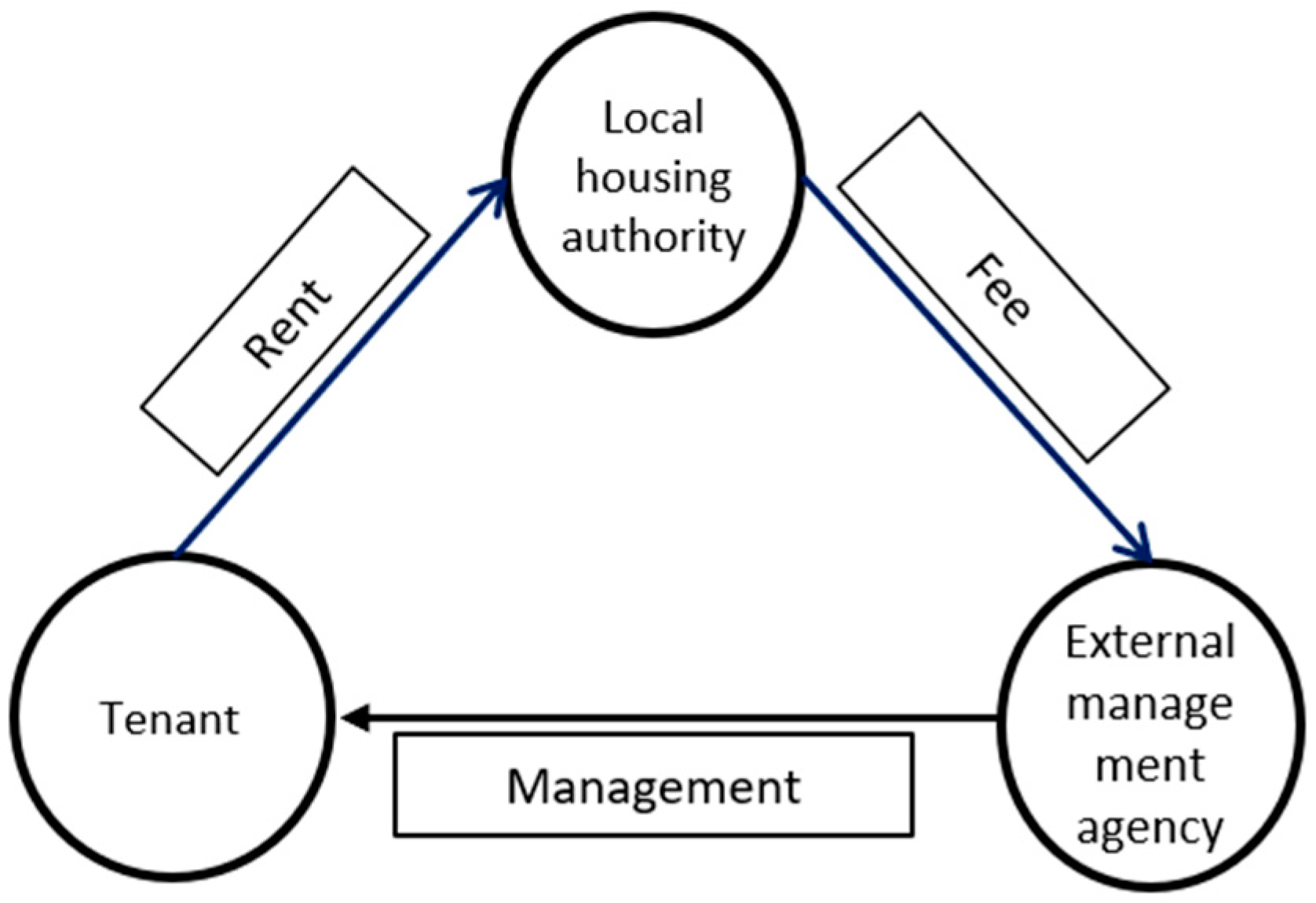

In some places, especially affluent municipalities, although external agencies participated in the PRHM, the property management fee was still borne by the LHA (

Figure 2). A typical example of this model is Beijing. According to the rental contract and local policies [

50,

51], the tenant paid rent to the LHA by a bank transfer. The LHA selected the property management company and covered all the property management fee. The property management company was only responsible for providing property management services to the tenant.

In this model, the relationship and allocation of responsibilities between the three participants were relatively clear. In terms of the service content, since the LHA bore all the management costs and was constrained by limited funding, the government required the EMA to give priority to the most basic and core services, like maintenance and repair. Moreover, in terms of funds, rent collection became vital. Only by ensuring adequate rent collection can the LHA maintain a balance between revenue and expenditure. Otherwise, the LHA needs to subsidize more. Once the management fee exceeded the budget ceiling of the LHA, this model was difficult to sustain. Then, the next management model emerges, in which the tenant was likely to pay some management fee (see

Section 4.3).

4.3. Separate Payment Model

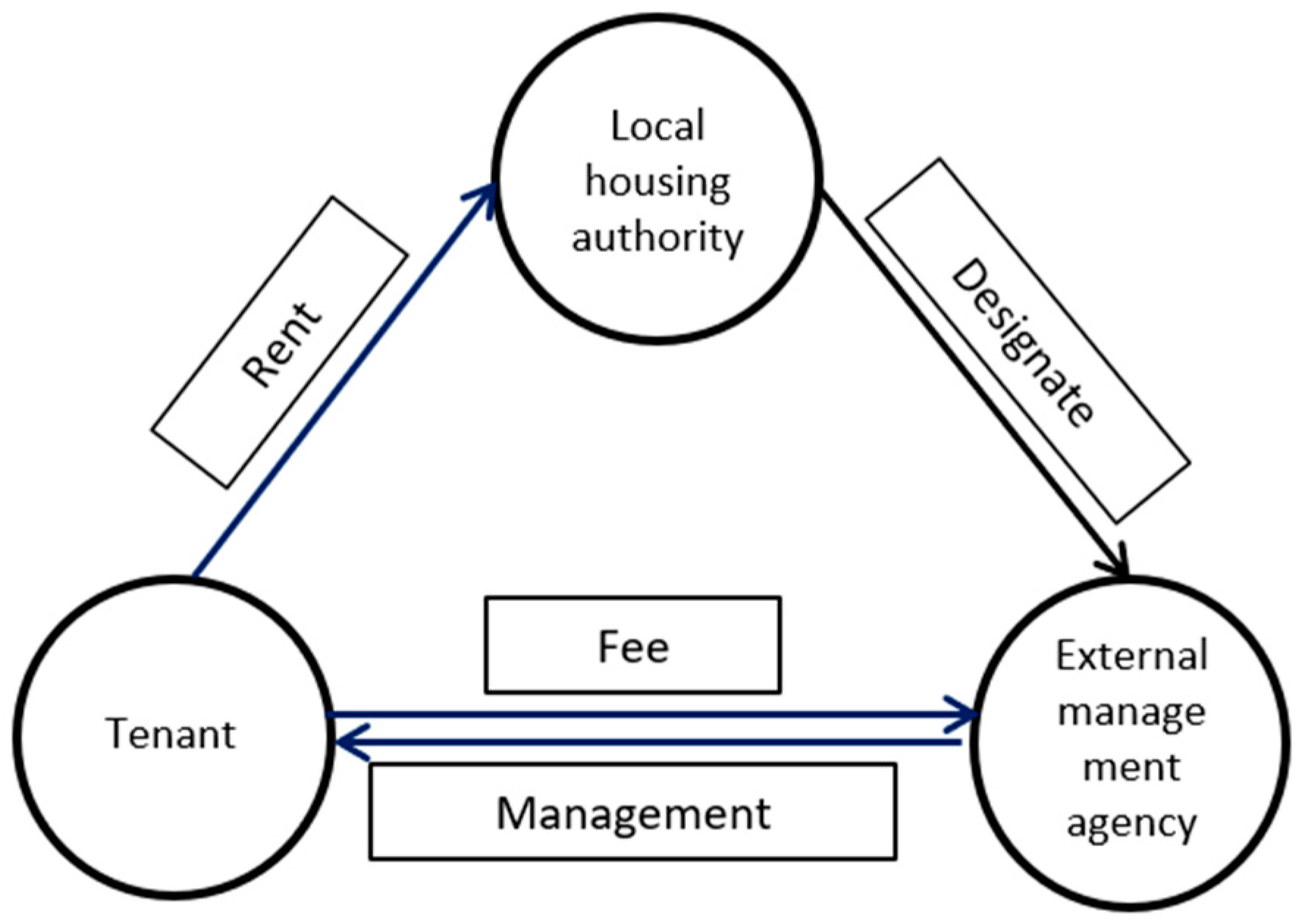

Compared with the previous model, apart from the rent, the tenant from the separate payment model needs to bear all or part of the management fee. According to the difference in the flow of funds, there were three co-existing sub-models in local practice.

First, the most common sub-model was that the tenant physically paid the rent and management fee to separate participants. Typical examples of this sub-model were in Wuhan and Chongqing. In this sub-model, the tenant paid the rent to the LHA by a bank transfer or direct debit. Meanwhile, the tenant also needed to pay the management fee to the EMA, which was selected or designated by the LHA (

Figure 3) [

36]. In this sub-model, the government’s specific management responsibilities and the financial pressure shifted at the same time. Taking the social welfare attributes into account, this sub-model and the whole model usually set a ceiling for the property management fee in PRH that was lower than the market price, such as CNY 1.44 per month per square meter in Wuhan [

52] and CNY 1.03 per month per square meter in Chongqing [

53].

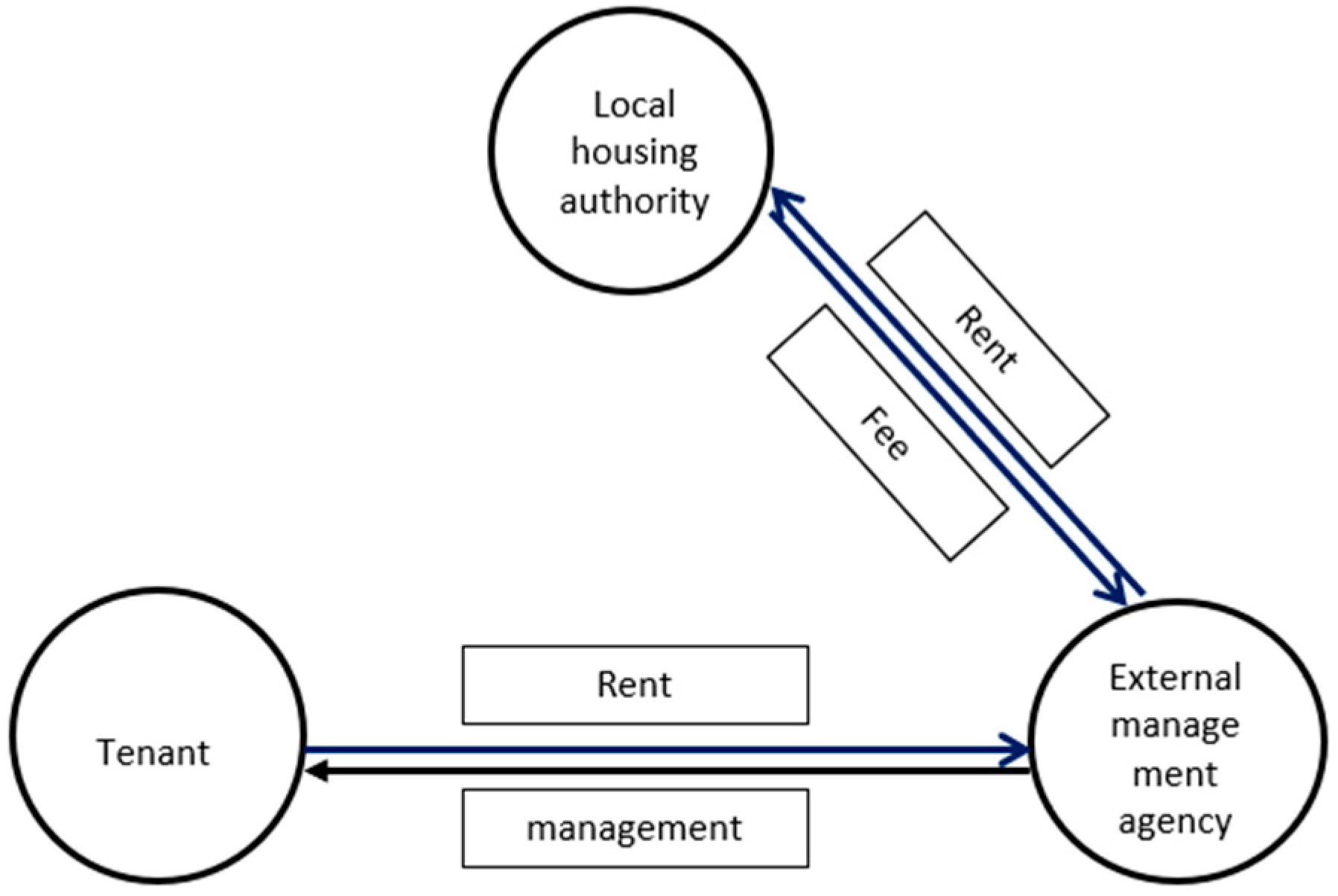

In this sub-model, the tenants knew that they paid the management fee to the EMA, so they were more willing to hand over PRHM-related issues to the agency rather than to communicate with the LHA. In particular, the tenants had little influence on the selection of the EMA, so they did not have a clear understanding of the services that would be provided, which was also a problem in the whole model. Moreover, the EMA had to collect the management fee on its own. If the fee could not be collected in full or on time, there were some financial risks.

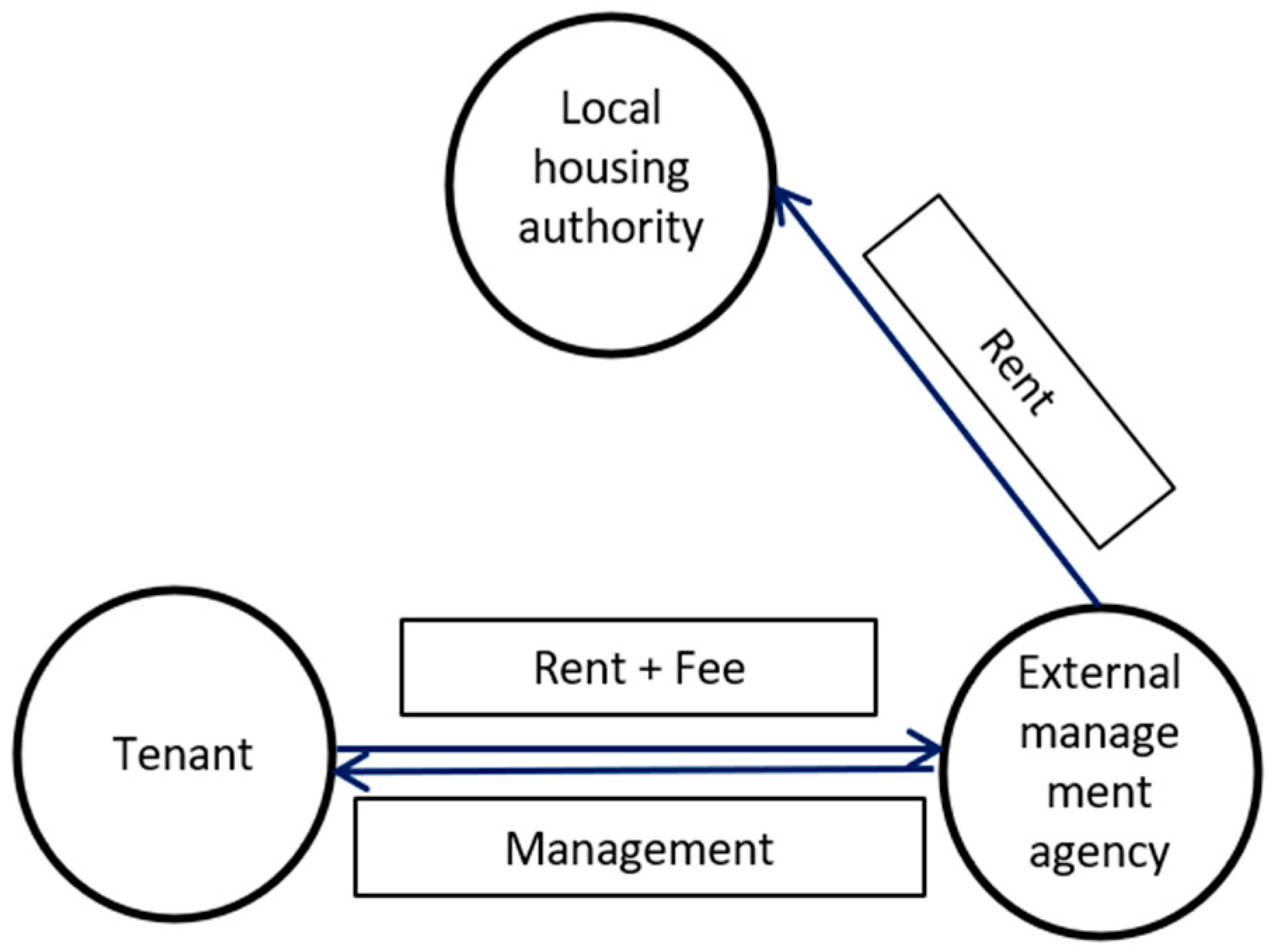

The second sub-model is where the EMA directly collected the rent and management fee from the tenant, and then handed in the rent to the LHA (

Figure 4) [

54]. A typical example is in Hengnan. Since the EMA staff had direct interaction with tenants almost every day, they were more closely linked. It seems convenient for the agency to collect rent. The staff could collect the rent and property management fee at the same time. This model, in theory, helped the LHA to increase the rate of rent collection. On the other hand, it could help the EMA to collect the property management fee through the form of bundling.

However, the problems with this sub-model are obvious. To begin with, it further weakened the relationship between the tenant and the LHA. In this sub-model, the tenant and the LHA had almost no direct economic and estate management interaction at the management phase. It is difficult for the LHA to fully understand resident’s satisfaction and economic status. Secondly, it is more difficult to distinguish the proportion of the rent and the management fee by charging both fees in a bundle. When the amount falls short, for self-interest’s sake, the EMA might prioritize the money it collects as the management fee rather than the rent. Meanwhile, the EMA reported the difficulty of rent collection to the LHA. As a result, the problem of non-payment would appear even more serious.

In the third sub-model, the LHA collected the rent and management fee at the same time, and then transferred the management fee to the EMA (

Figure 5) [

55,

56]. A typical example of this sub-model is in Hangzhou. In this sub-model, the LHA could motivate the property management company to improve services by means of differentiated payment. In addition, the relationship between the tenant and the LHA was not too loose.

In general, the separate payment model has several problems. To begin with, the affordability of PRH will decrease. In this model, the management fee was basically all borne by the tenant. Compared with the previous two models, the third model put more economic responsibility on the tenants, which can be considered as further privatization in the field of PRHM. Moreover, constrained by the charging ceiling, the service contents and service quality were also compromised. With limited revenue, the EMA could only provide a few basic services and constantly reduced the costs. However, there were still some EMAs that could not make ends meet. They could only quit during the contract [

52]. Thus, in some cities, such as Shenyang, the LHA still needed to subsidize some part of the management fee to keep the EMA in basic operation [

57]. In this scenario, the economic pressure on local public finance was still not alleviated much. Last, but not least, there were too many sub-models in this model. This diversity was a big challenge to clarifying the sharing of responsibilities between participants.

In sum, there were three main management models (

Table 3), from a monopoly model to a model of privatization and marketization. Although many LHAs tried to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of PRHM through introducing a professional agency, the participation of the external agency itself alone could not fundamentally improve the PRHM, but instead introduced the challenge of how to clearly confine their responsibility and control their performance.

4.4. Common Problems with the Former Models

Although the different models have separate difficulties, there are two common and prominent problems worth noting.

To begin with, the funding dilemma. As mentioned before, there are three main sources of funding for PRHM: the rent, the property management fee (if applicable), and local government subsidies if there is a funding gap. Firstly, all PRH rents in China are below the market prices. The rent income is actually very limited. In addition, part of the rental income needs to repay construction or purchase expenses. Taking Chongqing as an example, in 2011, the annual rental income of PRH was CNY 4.8 billion. Due to the short loan period, the repayment of principal and interest is as high as CNY 4.2 billion. So, the rental income that can be used for management is quite limited [

58]. Secondly, since the tenants of PRH are mainly from low- and moderate-income households, there is a limited amount that tenants can spend on housing. If they encounter unexpected strikers, there are cases of arrears of rent and being unable to pay the management fee [

13]. Therefore, the total amount from the first two funding sources is limited and unstable.

In addition, the process of collecting rent and management fee is overdiversified and inefficient [

15]. Under the premise that the total amount is not enough, collecting the rent and management fee in full and on time is essential for the PRHM. However, many of the tenants are economically disadvantaged, and it is difficult to directly expel them from a social welfare perspective. Although it is convenient to collect rents through a bank transfer or direct debit, there are always some tenants who refuse or are unable to pay for various reasons. Reengineering the charging process and seeking a more efficient way to collect the rent and management fee are critical.

In sum, inadequate and unstable funding sources and inefficient rent and management fee collection processes have meant that PRHM faces a serious funding problem.

Secondly, ambiguous management service contents. The LHA gave priority to property management, especially daily maintenance and repair, which coincides with one of the significant factors found in previous studies that affect residents’ satisfaction with PRH [

15,

59]. However, with the expansion of this housing program, the demands of the tenants and the goals of the LHA became more complicated. Some research points out that the demands of the tenants and the services provided by the EMA do not match [

60]. Moreover, affected by local financial capacity and the overdiversification of management models (sub-models), there are huge differences in management contents across the country. Tenants lack a clear understanding of what services the EMA will provide. The specific tasks that the EMA will undertake should be further clarified.

Facing funding dilemmas and ambiguous management service contents, even with the participation of an external agency, PRHM has to be fundamentally improved and needs further optimization.

5. New Policy Responses

In view of the serious aforementioned problems, MOHURD began to shift its focus to the management of PRH [

61]. According to the policy text, the shortage of professionals, the low level of service and irregular management are increasingly prominent [

28]. We can safely assume that the ministries had already perceived the main problems and the new scheme was intended to address them. In light of this, two objectives were proposed: firstly, improving management professionalism; secondly, improving residents’ satisfaction. Accordingly, some new measures were put forward.

5.1. New Measures

In the face of the existing problems in the previous management models, the new policy responds to three main aspects.

5.1.1. Government Procurement was Compulsorily Introduced to Select External Participants

To begin with, the method of government procurement was formally and compulsorily introduced to select the EMA in the hope of improving the professionalism of PRHM. Compared with the direct provision of services by the LHA, government procurement can find a more professional external agency and directly solve the problem of shortage of personnel. In addition, government procurement is more likely to stimulate competition and save more than directly designating the management tasks to a government-invested platform. The assumption behind the change was that the participation of external participants and market-oriented competition would overcome the financial and administrative inefficiency [

26,

62].

5.1.2. The Local Financial Budget Would Bear the Management Fee

The financial arrangement was restructured in order to solve the problem of funding. In the pilot provinces, the management fee can be included in the LHA’s financial budget. According to the data collected so far, the pilot projects have not increased the rent. More importantly, the rent is rising very slowly and adjusted every two years. The management costs are now borne by the local public budget through government procurement. Thus, for the tenants, the affordability of PRH has risen.

In contrast to many Western countries, which have been moving towards the privatization of the public rental sector management [

47,

63], Chinese public finance was supposed to take on a greater share of the burden in the new policy. As the property owner of PRH and the implementor of the social welfare policy, the LHA has a substantial responsibility for maintaining the proper operation and functioning of PRH. Therefore, in order to solve the current funding dilemma, it seems like a good approach for the local budget to provide stable and reliable financial support.

5.1.3. More Service Contents Were Included in the New Policy

The new policy explicitly expanded the PRHM boundaries and is expected to improve residents’ satisfaction by offering a variety of services. The new policy proposed four categories of guided procurement contents (

Table 4). These four categories of services far exceed what was available in most places before the policy came into effect.

In addition to basic maintenance and repair, there are some service contents that deserve to be highlighted. To start with, the rent collection task is transferred to the EMA. Moreover, more attention has been paid to residents’ satisfaction. The new policy expected more than just daily property management. From the guided procurement contents, we can clearly perceive that the ministries are trying to achieve socially, technologically and financially sustainable development. According to the procurement contents, a new management model is shown below (

Figure 6).

In theory, all three new measures seem to lay the groundwork for achieving the final objectives and solving the main problems with the previous models (

Table 5). To start with, government procurement has many statutory constraints that provide the basis for selecting the most professional and economical EMA. Furthermore, the public finance, rather than the tenant, will bear all the management fee. This would also alleviate the external agency’s concerns about the instability of the funding sources. Last, but not least, with the expansion of the service content and the increased emphasis on residents’ satisfaction, we expect that this objective will be achieved.

Furthermore, the measures have many similarities with reform programs in Western countries (

Section 3). The new management scheme is a modest privatization reform. Despite the EMA’s full participation in PRHM, the government still bears significant economic responsibility. Besides, with public financial support, more management services are proposed. However, unlike ALMO or CHP, the EMA is heavily dependent on public finance. In the Chinese context, the EMA has very limited channels to make a profit other than public subsidies.

Among the three measures, the introduction of government procurement is compulsory because it is regulated by a series of statutory laws. However, the second and third measures are less mandatory. The second measure is heavily dependent on local finances, which vary greatly from place to place. The last measure is a guiding content proposed by the ministries, so it leaves a certain scope for discretion.

5.2. Obstacles of the New Policy

It is worth noting that the new policy, although much improved, still has some limitations in two aspects. Firstly, the funding is largely reliant on local public finances. In the new scheme, the central government still does not provide subsidies to PRHM. The financial status of local governments will strongly affect the implementation of the new policy.

It is worth noting that, even in the face of possible local financial constraints, the Public–Private–Partnership (PPP) model which is commonly used abroad [

64] has not been adopted in the new policy. This mainly has the following reasons: to begin with, although the government pays more and more attention to the application of PPP in the provision phase of public rental housing (PRH), most of the existing PRHs are directly invested by the government (

Table 1). In addition, in the allocation and management phase, the discretionary power of the EMA is very limited. For example, the EMA cannot determine the rent price. The management fee is also regulated by the government and is lower than the market management price. The EMA also does not review the eligibility for the tenant. So, in the management phase, the profitability of the EMA is not high. Last, but not the least, as mentioned in

Section 4, it is difficult for the EMA to collect rent on time and in full of old management models. It is difficult to maintain a financial balance for the EMA. In conclusion, excessive financial risks and limited profitability make it difficult to stimulate private capital to establish partnerships with the government in the management phase.

Therefore, at the policy design stage, the PPP was not adopted. Rather, in order to eliminate the EMA’s economic concerns, the method of government procurement was proposed, and the local finance would bear all management fees.

Secondly, in terms of the guided procurement contents, we could argue that the new policy seems too ambitious. To start with, some procurement contents in the fourth category, such as technological improvements, are largely absent from the existing management services. The rapid expansion of management contents is a major challenge for both the LHA and the EMA. In addition, the essential task of rent collection was transferred to the EMA. The LHA can legally transfer the pressure and risk of rent collection to the EMA through government procurement. The EMA is liable for the full collection of rent on time, and the risk of nonpayment would be partially borne by the EMA. However, the enforcement power of the EMA is obviously weaker than that of the LHA, which is an obstacle to the full implementation of the new policy.

In sum, the new scheme has some obstacles in its design. There is a paradox about financial capacity and service contents. For an LHA with low financial budget, it is difficult to implement a grand plan with insufficient resources. The obstacles in policy design have planted clues for deviations in implementation.

6. What is the Real Situation in Practice?

After one year of practice, it is time to reflect on the current implementation. This exploratory research provides some insights into a better PRHM scheme. We collected 19 projects from provincial government procurement websites (

Table 6). These 19 projects came from six pilot provinces, which were widely distributed in different regions of China. In addition, we interviewed three project executives, two from Guilin, and one from Tianyang.

The criteria for selecting these projects are as follows: firstly, the diversity of the projects. The project scale, the economic development level of the project site, and the government’s administrative hierarchy level (from prefecture-level city to county) of each project are quite different. Compared with the following projects, the first six projects are from the eastern coastal area (

Table 6 and

Figure 7), which is the most economically developed place in China. The local financial capacity of the first six pilot projects is relatively stronger, which has an impact on subsequent procurement contents and payment. The diversity of these projects can help us fully understand the implementation of the new scheme on the ground. Secondly, the representativeness of the projects. Since the reform began, the above six pilot provinces have selected pilot cities (counties) within their respective administrative divisions. We have only selected cases from the target pilot areas to ensure that they were all subject to the same scheme. Even though there are some similar government procurement projects in nonpilot areas, we have not included them in the analysis.

6.1. The New Compulsory Method Was Widely and Strictly Implemented

The method, namely government procurement, was widely adopted to select the best EMA. All the projects strictly followed the government procurement law. Firstly, in terms of procurement approach, with the exception of the 1st and 4th projects, which used the less competitive single-source procurement approach, the remainder adopted more competitive approaches, like public tendering and competitive negotiation. The vast majority of projects had more than three bidders. Both the government-invested platforms and private companies were required to participate in the bidding on an equal basis and followed the same criteria for evaluation.

Secondly, in terms of the evaluation committee, all the successful bidders were selected by a committee of experts and government officials. However, there are no mandatory provisions on the participation of stakeholders (i.e., tenant in this study) in the Government Procurement Law. According to the information collected so far, there has been no project in which tenant representatives have been invited to join the committee. For example, in the 14th project, the committee consisted of three members. One represented the LHA. The other two were randomly drawn from the provincial procurement evaluation expert tank, while one had an economic and legal background and the other had a real estate management background. The second project also had a very similar evaluation committee. Such a committee of three experts is both legitimate and easily convened. The participation of tenants will take more time and is not mandatory. So, this kind of compact committee is more commonly adopted in practice. This is quite different from the experience in the West, which generally values the participation of tenants in different aspects, such as improvement of building standard, deciding services contents and priorities, assessment of service contractors’ performance and so on [

65,

66].

Thirdly, in terms of procurement proceedings, all potential suppliers were subject to multiple reviews. All candidates went through a first round of qualification checks when they submitted their materials at the beginning of the bidding process. On top of that, the committee selected the most qualified bidder according to a comprehensive set of indicators. Still taking the 14th project as an example, the main evaluation indicators were service contents, quotation and personnel. These three items accounted for 85% of the evaluation score. This evaluation index reflected the government’s priorities for the whole procurement.

In closing, we argue that the management professionalism would be upgraded. With the enforcement in law as a guarantee, government procurement can indeed facilitate the selection of a professional EMA. Meanwhile, through competition, financial savings could also be expected.

6.2. Diversification of Actual Procurement Contents

The new policy proposed clear and ambitious guidance on procurement contents, but also gave the LHA discretion. From past experience, the service of most concern for PRHM was repair and maintenance [

12,

15], which was also the case with the new scheme. From the perspective of procurement contents, all 19 projects included this as core content in the contracts (

Table 7). However, the fourth category of guided procurement contents, namely the comprehensive affairs, was of least concern.

From the 19 projects, we observed three different categories (

Table 7). The first category was projects that were very similar to the guided procurement contents. In this category, the procurement contents coincided to a great extent with the guided procurement contents. Taking the 16th project as an example, if we look closely at its bidding documentation and contract details, we find that it almost exactly copied the guided procurement contents from the new policy.

The second category was projects with concentrated procurement contents. Some LHAs condensed some procured contents. In some projects, the LHAs still only cared about core services, so they eliminated most of the guided procurement contents from the bidding documentation and only procured the core contents, namely repair and maintenance. One important reason for this selective implementation was financial pressure. According to the new policy, the management fee would be borne by the local financial budget. However, if the local public financing was not adequate, then the budget for paying the procurement was also limited.

Currently, our (local housing authority) main task is to provide a livable dwelling for low- and moderate-income people, and to maintain it in good operation. … Of course, we know and record the inventory of PRH, the basic information of the tenants, and so on. But procuring an authentic intelligent management system at a high price is beyond our [financial] ability.

—interview with a staff member of the 17th project

The third category was projects with extended procurement contents. From past management experience, some LHAs have already discovered the diversified demands of tenants and begun to provide more welfare services when financially permitted. Therefore, some projects had made it clear that, in addition to providing the guided procurement contents, the LHA also procured some supportive services, such as regularly visiting and helping elderly people who are living alone. These extended procurement contents are similar to the “housing plus” features in Western countries [

67]. The cost of these projects is higher since these supportive services are included in the contract. They rely on more public subsidies and thus normally exist in more affluent jurisdictions (eastern area).

Since there were still no central government financial subsidies and rising rent, the actual procurement contents were closely related to the local finances. This is also clearly demonstrated from

Table 7. Well-developed eastern areas usually had an adequate budget, so most of the projects from these areas were in the extended procurement contents category. Constrained by the local financial capacity, in the less-developed western provinces, most projects were in the concentrated procurement contents category.

6.3. Inconsistent Financial Arrangements

In addition to the deviations in procurement contents, there were also certain differences in the financial arrangements in local implementation. To start with, although the new policy proposed that the management fee could be covered by the local public budget, in some projects, the management fee was still apportioned by the LHA and the tenant (

Table 8). For example, in project 11, public finances covered 34% of the final bidding price, and the EMA will still collect the remaining part of the management fee from the tenant. It is not difficult to see that four out of the five projects that explicitly stated that the management fee would be shared came from the less developed western and central areas. In order to fulfill the pilot tasks, some LHAs had to make some compromises. For LHAs from less-developed areas, it was very difficult to cover all management fee independently.

Secondly, there are inconsistencies in the key indicators of public finance differentiated payments. The differentiated payment is often adopted to encourage the EMA to do a better job. However, due to the different priorities of the LHAs, the key indicator varies largely. For example, some of the projects have fully considered achieving the objective of improving residents’ satisfaction. The sixth project made it clear that, if the overall residents’ satisfaction rate is lower than 90%, 1%‒5% of the management fee will be deducted. In contrast, in order to solve the problem of insufficient funds, the second project clearly stated that if the rent collection rate does not reach 95%, 5% of the management fee will be deducted. The risk of nonpayment is partially borne by the EMA. The key indicator of differentiated payment guides the work of the EMA. The key indicator of differentiated payments plays an important role in the fulfillment of the objectives.

In sum, many deviations have taken place in the local implementation of the new policy. Although the ministries had high expectations for this new policy, the outcomes of the pilot scheme were doubtful. The new scheme had not changed fundamentally in terms of funding. In light of this, the guided procurement contents looked a bit ambitious. Some of the technological and social improvements would not be procured because they had little impact on the PRHM in the short term.

7. Discussion of the New Scheme

Piloting in different areas to test the new scheme is important. Practice has already demonstrated the shortcomings of the new scheme and makes us constantly reflect on how to manage PRH in a better way.

7.1. Very Few Projects Had Fully Implemented All Three Measures of the New Policy

Strictly speaking, only in three projects has the new scheme been fully implemented in terms of government procurement, financial arrangement and service contents. It has not been easy to implement without financial support. The new method, government procurement, was most commonly followed. However, when it comes to the service contents and financial arrangement, only three of the 19 projects were fully compliant with the new policy. In the 3rd, 10th and 16th projects, the actual procurement contents covered all four categories of services proposed by the new policy. Even some expensive technology upgrades were procured. In addition, these three projects also explicitly stated that the management costs would be completely covered by public finance. The economic burden on tenants did not rise, while they were able to enjoy more services. Overall, these three projects are representative of the new scheme.

7.2. Two Compromise Strategies Emerged and Some Projects Went Back to the Former Management Model

Some of the measures proposed by the new policy do not have enough financial support. Therefore, lacking the funds to completely fulfill the national pilot task, some LHAs had to adopt new strategies (

Table 9).

Compromise strategy 1: compress the procurement contents. Some LHAs spent the limited budget on procuring what matters the most. The application of this strategy seemed like a way of returning to the previous government-paid management fee model (

Figure 2). For example, the 2nd, 14th, 15th and 18th projects compressed the service content and the management fee was borne by the LHA. These projects procured the minimum service content, i.e., repair and maintenance, to keep the PRH in basic operation and rarely complied with the guided procurement contents. However, these projects at least solved the problem of financial instability and increased the affordability of PRH.

Compromise strategy 2: share the management fee between the LHA and the tenant. Another solution to the paradox of limited funding and ambitious services was to share the management fee with the tenant. In some projects, the actual services procured overlapped significantly with the guided procurement contents, while the management fee was divided into two parts. The adoption of this strategy meant that some of the projects had many similarities with the previous external management agency in charge sub-model (

Figure 4). Taking the 11th and 12th projects as examples, the services procured were almost identical with the new policy. The rent was collected by the EMA, which then turned it over to the LHA. Meanwhile, the tenant paid 36% to 66% of the management fee to the EMA and the remaining part came directly from the public fund. Although these projects still required the tenant to bear part of the management fee, the services they could expect were much clearer and obviously expanded.

In addition to adopting a single strategy, there are projects that employed both strategies. That is, compressing the services while sharing the costs. As mentioned earlier (

Section 4), some of the guided procurement contents proposed by the new policy are worth reflecting on. The typical one would be rent collection. Since it is one of the main sources of the management fee, how to collect rent in an effective and efficient way was essential for the whole PRHM. In the new policy, for the second category of guided procurement content, the responsibility for rent collection transferred to the EMA. However, this change was risky. Actually, we found that some projects did not shift this task to the external agency.

In terms of not transferring the rent collection task to the EMA (which means partial compression of guided procurement contents) and sharing the management fee, we observed that some projects had many similarities with the total separate payment management sub-model (

Figure 3). Typical examples are the 6th, 17th, and 19th projects. All of these projects came from the concentrated procurement contents category. So, the procured services were limited. Moreover, in these projects, the tenant needed to pay the rent to the LHA and pay part of the management fee to the EMA.

In sum, the adoption of these strategies will greatly compromise the effectiveness of the reform and even cause some projects to revert to the previous management model.

7.3. Given the Rare Projects of Full Implementation, the First Compromise Strategy Would Be More Preferable and Feasible for Achieving Reform Objectives

With the exception of the three projects that fully implemented the new policy, most projects were implemented with some degree of deviation. Comparing the two compromise strategies, in response to the two reform objectives, namely improving management professionalism and residents’ satisfaction, retaining the core tasks and paying the management fee from local public finances would be a more feasible approach.

To start with, the adoption of government procurement as a compulsory method helped to achieve professional management. Of the three major changes to the policy, government procurement was the best implemented. The statutory provisions of the government procurement law combated the arbitrary manner of selecting the EMA. Committees composed of experts and government representatives could help to balance the professional and economic perspectives. Actually, we found that all 19 successful bidders were qualified and experienced real estate management agencies. Thus, the first objective is achievable.

More importantly, when it comes to residents’ satisfaction, we have to look again at the actual services procured and the financial arrangements. Although the conclusions on factors affecting residents’ satisfaction in PRH were inconsistent, in general, affordability (including the rent and other fees) [

68,

69,

70] and the core task of property management (repair and maintenance) [

15,

59] are the most significant factors. We found that all 19 projects included repair and maintenance in the procured services (

Table 7). Therefore, we can reasonably infer that even if some LHAs adopted the compressing service strategy, repair and maintenance would be the last services to be eliminated from the contract. In other words, improving affordability is a more feasible way to improve residents’ satisfaction with PRH.

For PRH tenants, as long as the core management service is provided, the affordability of PRH is their highest priority. In light of the social welfare attributes of PRH and the reform objectives, if some local housing authorities cannot afford to procure all the guided procurement contents, they can still achieve the objective of improving residents’ satisfaction by cutting down some of the services and covering all of the management fee.

7.4. The New Policy and Its Implementation Failed to Fundamentally Solve the Main Problems of PRHM

The launch of the new scheme is a response to the problems with the previous management models. First, in terms of the policy design process, the three measures tried to address the main difficulties. However, there is not enough financial support for these measures. Insufficient resources and the ambitious guided procurement contents were at odds. Therefore, it is very difficult for this policy to be fully implemented and to solve the previous problems.

Furthermore, it is common for projects to deviate from the full implementation of this policy. In order to fulfill the reforms, many LHAs adopted a series of compromise strategies. So, it is not difficult to see that, in addition to the problem of a shortage of manpower, which can be solved by the introduction of professional agencies, the problems of insufficient and unstable funds, overdiversified management models, and ambiguous service contents remained unsolved in the new scheme. Overall, the new scheme is insufficient to solve the main problems of PRHM, in terms of both policy design and implementation.

8. Implications and Conclusions

In theory, the new policy is well intended. Government procurement is formally engaged to select a professional EMA. Public finances are supposed to take more responsibilities. For the first time, the PRHM service has clear national guidelines. However, the policy design is not perfect. There are still some obstacles. Afterwards, many deviations were also found during its implementation. Some projects even reverted to the former management models. The outcomes of the new scheme are uncertain.

To sum up, the new scheme would be more successful if we could make some adjustments to the following three aspects.

Firstly, remove rent collection from the guided procurement contents. If the tenant is willing and able to pay the rent, it is not technically difficult to collect it, especially in China, where mobile payment is well developed. Unless the tenant’s economic capability or service quality is indeed improved, asking the EMA to collect rent will not fundamentally solve the problem of nonpayment, but will increase the cost of procurement. A full analysis of rent collection can help the LHA understand the economic status of the tenant and the residents’ satisfaction. Therefore, it is preferable for the tenant to pay the rent directly to the LHA through mobile payments or a bank transfer.

Secondly, residents’ satisfaction should become the key indicator of the differentiated payment of public funds. Government procurement can be conducive to achieving the objectives of professional management. However, residents’ satisfaction is not going to be improved by introducing a professional EMA. In order to fulfill the reform objectives and enhance the supervision of EMAs, residents’ satisfaction should become the key indicator of differentiated payment of public funds. Through this adjustment, the reform objectives are more likely to be achieved.

Thirdly, invite tenants to participate in the government procurement process. In this top-down reform, the target group, namely the tenants, has hardly any voice. The documents collected so far demonstrated that all evaluation committees were composed of government representatives and experts, while the tenants had little influence on deciding the service providers and service contents. Inviting tenants to participate in the procurement process can be an effective means of bridging the gap between the government’s intentions and the actual demands.

Although the scheme has some flaws in terms of the policy design and implementation, on the whole, it has merit. It solves some of the existing problems. Moreover, even if there are some deviations, it is still possible to achieve the reform objectives. If it can be further adjusted, the scheme will be more likely to improve the management of public rental housing.