Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Complementary Currencies: The Base

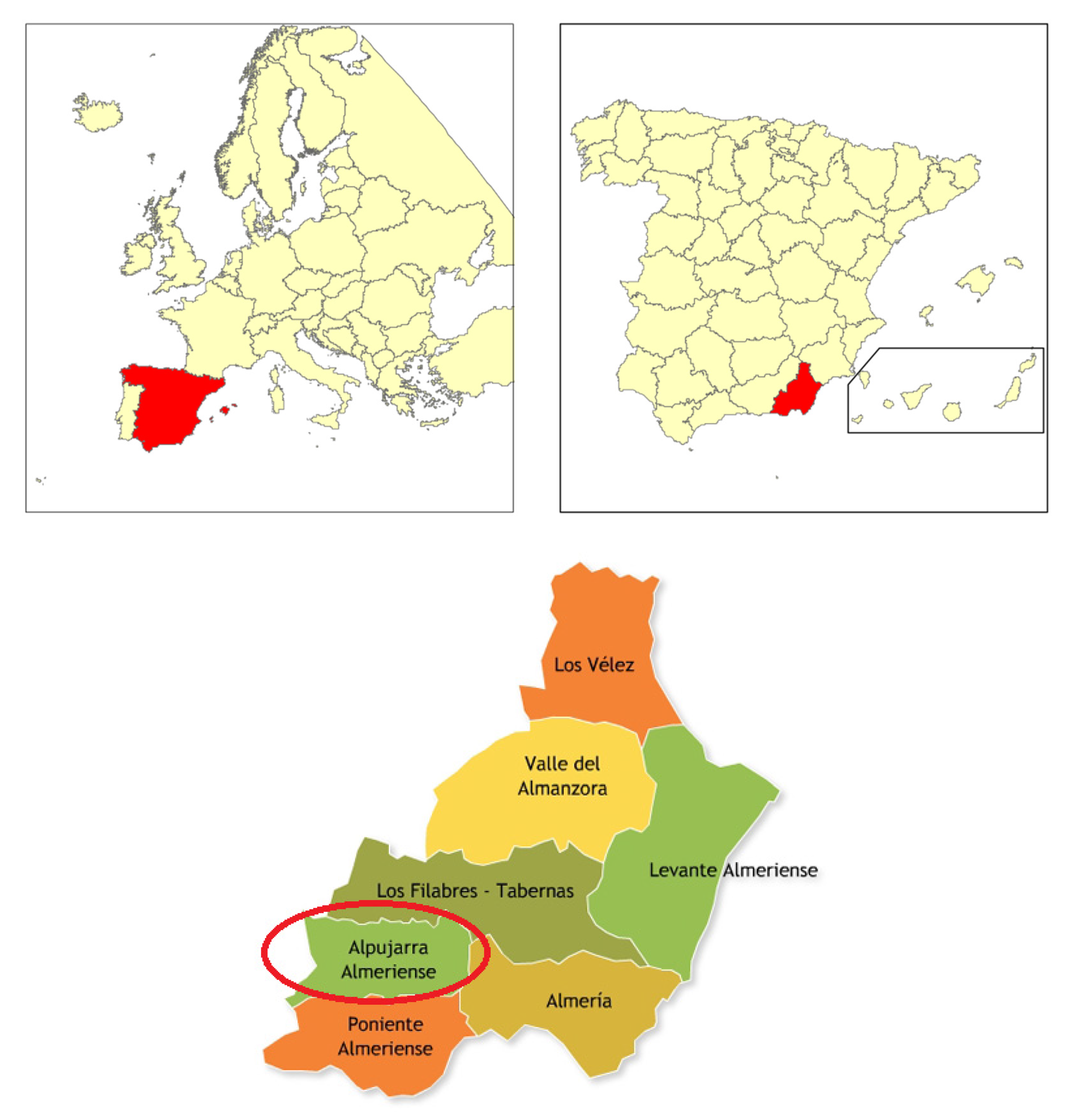

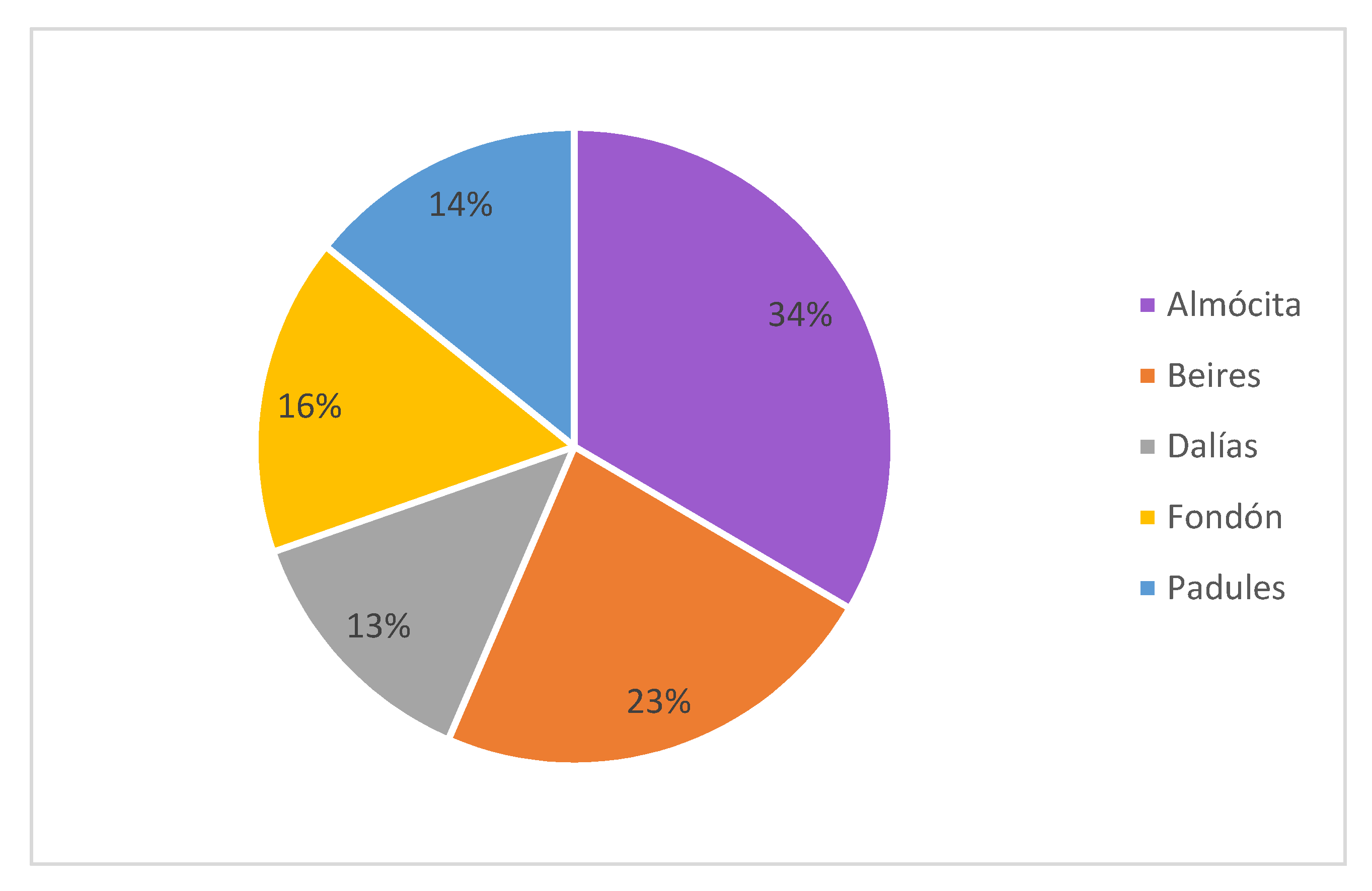

2.2. Study Region

2.3. Creation Process

- Step 1.

- A detailed analysis of the region/territory must be carried out and the needs and resources available must be studied. These resources can support the issuance of the coins. Once this is carried out, the objective of the social currency should be established together with identifying unmet needs, the resources, and the people to whom it is directed. Once these basic characteristics are established, the broad type of social currency is selected: Time Banks, LETS, physical social currency, commercial barter, etc. Goals and specific deadlines should be set to systematically collect all the information in such a way that it can easily be used in the subsequent steps.

- Step 2.

- A highly representative group should be created which involves all the important sectors in order that they can contribute their ideas and see themselves reflected in the proposed currency. The community that will use this payment method must be developed and updated at all times. It is necessary that the process of creating the currency is communal and that everyone feels involved and part of the project. The training received must always be maintained and it is recommended that there be spaces available wherein the community can be updated or learn about the current state of affairs.

- Step 3.

- The type of currency and its representation are definitely chosen, along with the accompanying merchandise, currency, or electronic media. A design is tailored to the purpose of the coin. Once this is done, the form with which it will be supported and the value that will be minted are selected: official money, provision of services, etc.

- Step 4.

- Once there is a general outline of the currency´s structure, the manner in which to execute it must be determined, including a mechanism for covering all related costs. These costs can range from the most basic, such as facilities to be developed, to other more direct costs, such as the printing of the currency. Its implementation can be supported by other institutions, such as foundations, the premises themselves, or public entities such as municipalities that may be willing to contribute. In order to recover the expenses, it may be necessary to establish fees such as transaction or interest for the use, oxidation to avoid its accumulation, or a participation fee.

- Step 5.

- Finally, it is important to establish a scheme that shows how this tool is going to be issued, put into circulation, and how withdrawals will be made. It is a tool that must satisfy the needs of consumers at all times. Following this, a testing phase should be carried out to check whether it works or not.

- Step 6.

- Similar to any other action, an evaluation process of the basic indicators must remain open at all times, and, if necessary, the system should be recalibrated in order that its launch be as smooth as possible.

3. Methodology

- -

- Eight show local opinion: five from the habitual residents and three from relevant businesses and economic weight in the municipality.

- -

- The remaining two are the opinion of people domiciled in the municipality but who are not residents.

4. Results

- -

- The local council promotes activities to avoid depopulation and favor the settlement of new people in the municipality.

- -

- In addition, it is amenable and actively participates in the discussions. The local inhabitants have great trust in this entity.

- -

- The local council listens to new proposals without rejecting them outright even when financing is required. They state that one of these proposals is related to social currencies and has been discussed on more than one occasion, albeit superficially.

- -

- The town has a health center, a school and a pharmacy.

- -

- The small retail businesses in the municipality speak of problems for their subsistence, although they do not have direct competition around them: lack of change due to sales, complicated maintenance of some types of products, etc.

- -

- Of the two bar/restaurant services that exist, the bar, which recently reopened following a change of ownership, is the only establishment that consistently remains open. The restaurant only opens on weekends except for in the summer months when it is opened on a daily basis.

- -

- The owners of the bar have known complementary currency initiatives.

- -

- There are good public transportation links to the capital which run approximately three times a day.

- -

- Nearby municipalities are well connected and include various hiking trails and a bike path.

- -

- The residents take an active part in municipality events and matters and detect depopulation as a factor that must be eradicated.

- -

- There is no direct rejection of people from outside the municipality.

- -

- The average age of the population is quite high.

- -

- The inhabitants highly value the cultural programs in which they participate.

- -

- There is a lack of significant generational replacement, a problem that also exists in neighboring municipalities.

- -

- There is a strong feeling of belonging to the locality, although limited employment possibilities make it difficult to maintain the population.

- -

- The real population does not coincide with the official census population.

- -

- In terms of average income, their amount is greater than expenses incurred.

- -

- The municipality has people who have knowledge of the issue of social currencies, for example, of the drivers of la Pita. In turn, some have reacted positively to whether or not they knew of the existence of websites such as “vivirsinempleo.org”, which highlight, among others, issues related to CC.

- -

- The ecological approach which is established in the municipality is promoted as a resource which can attract newcomers to the area.

- -

- The state of heritage preservation of the town is very good.

- -

- There is little exploitation in the tourist potential of the town, and its denomination as a pueblo alpujarreño (mountain town).

- -

- The town possesses its own unique resource, the largest lamp in the world.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Corrons, A. Monedas complementarias: Dinero con valores. RIO 2017, 18, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietaer, B.A.; Hallsmith, W. Currency Guide. Available online: http://community-currency.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/lietaer-hallsmith-community-currency-guide.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2019).

- Vandeaele, J.; Walsche, A. La Crisis es una Oportunidad. Mondial Nieuws. Available online: https://www.mo.be/es/artikel/entrevista-con-experto-financiero-bernard-lietaer-la-crisis-es-una-oportunidad (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Dittmer, K. Local currencies for purposive degrowth? A quality check of some proposals for changing money-as-usual. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, M.Y. Monedas sociales y complementarias (MSC). Oikonomics 2016, 6, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, G. Making Markets. The Institutional Rise and Decline of the Argentine Red de Trueque. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto de Estudios Sociales, La Haya, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pacione, M. Local money—A response to the globalisation of capital? Quastiones Geogr. 2011, 30, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Richey, S. Manufacturing trust: Community currencies and the creation of social capital. Polit Behav. 2007, 29, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-García, C. Bancos de Tiempo: Comunidades e Internet. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ULMER GELD: “WÄRA”. 1931. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20070416032710/http://hometown.aol.de/tmirabeau/Waera.html (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Kultur Wörgl. Available online: http://heimat.woergl.at/verschiedenes/freigeld-woergl (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Hirota, Y. Monedas Complementarias Como Herramienta Para Fortalecer la ECONOMÍA Social. Available online: https://www.economiasolidaria.org/files/Crisis_Economica_e_Instrumentos_Economicos_Solidarios.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- European Business Review. Available online: https://www.europeanbusinessreview.eu/page.asp?pid=2731 (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Calgary Dollars. Available online: http://www.calgarydollars.ca/about/ (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Chiemgauer-Statistik. Available online: https://www.chiemgauer.info/fileadmin/user_upload/Dateien_Verein/Chiemgauer-Statistik.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Berkshares INC. Available online: http://berkshares.org (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Brixton Pound. Available online: http://brixtonpound.org/what (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Orania Voorgrond. Available online: https://issuu.com/oraniabeweging/docs/orania_voorgrond_jul_2011 (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- FullCrypto: E-Ora. Available online: https://fullycrypto.com/orania-plans-to-launch-the-e-ora-as-currency-for-its-citizens (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Community Exchange Network Tasmania. Available online: http://cent.net.au/ (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Joachain, H.; Klopfert, F. Smarter than metering? Coupling smart meters and complementary currencies to reinforce the motivation of households for energy savings. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 105, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, C.; Papaoikonomou, E. Time banking in Spain: Exploring their structure, management and users’ profile. Rev. Int. Sociol. 2016, 74, e028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Michel, A.; Hudon, M. Community currencies and sustainable development: A systematic review. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Belmonte, S. Cómo Hacer una Moneda Social, La Aventura de Aprender. Available online: http://laaventuradeaprender.educalab.es/guias/como-hacer-una-moneda-social (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Greco, T.H. The End of Money and the Future of Civilization; Chelsea Green Publishing Company: Windsor, VT, USA, 2009; pp. 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sahakian, M. Complementary currencies: What opportunities for sustainable consumption in times of crisis and beyond? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2014, 10, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fare, M.; Ould, P. Complementary currency systems and their ability to support economic and social changes. Dev. Chang. 2017, 48, 847–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, J.; Fare, M. Understanding the role of governments and administrations in the implementation of community and complementary currencies. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2013, 84, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Community currencies: Small change for a green economy. Environ. Plan. 2001, 33, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, E. Monedas complementarias y ambiente. Cuides 2013, 10, 111–147. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, G.; Arango, P. Monedas locales: Servicios educativos y trueque líquido. Sophia 2013, 9, 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, C.; Hudon, M. Alternative organizations in finance: Commoning in complementary currencies. Organization 2017, 24, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiropoulou, I. Exchange Networks and Parallel Currencies: Theoretical Approaches and the Case of Greece. In Economics. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Crete, Rethymnon, Greece, November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfang, G.; Longhurst, N. Growing green money? Mapping community currencies for sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Money that makes a change: Community currencies, north and south. Gend. Dev. 2001, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, L. Spending time locally: The benefit of time banks for local economies. Local Econ. 2009, 24, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.; Lietaer, B.A. Regionalwährungen: Neue Wege zu Nachhaltigem Wohlstand; Riemann: Múnich, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lietaer, B.A. Das Geld der Zukunft; Riemann: Múnich, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fare, M.; Ould, P. Why are complementary currency systems difficult to grasp within conventional economics? Rev. Interv. Écono. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collom, E. Community currency in the United States: The social environments in which it emerges and survives. Environ. Plan. A 2005, 37, 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E. Community currency (CCs) in Spain: An empirical study of their social effects. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Longhurst, N. What influences the diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability? Investigating community currency niches. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. Denationalisation of Money: An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies; The Institute of Economic Affairs: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, M.S. Complementary currencies: History, theory, prospects. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, P. Complementary currencies. In Routledge Companion to Alternative Organization; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 182–194. [Google Scholar]

- European Central Bank: Virtual Currency Schemes. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/virtualcurrencyschemes201210en.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Fare, M. Les monnaies sociales et complementaires dans les dynamiques territoriales: Potentialités, impacts, limites et perspectives. In Proceedings of the Communication à l’UNRISD Conférence, Potential and Limits of Social and Solidarity Economy, Geneva, Switzerland, 6–8 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, G. The Nature of Money; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bitcoin, una Aproximación Jurídica al Fenómeno de la Desmaterialización y Privatización del Dinero. Available online: https://studylib.es/doc/8030153/bitcoin.-una-aproximaci%C3%B3n-jur%C3%ADdica-al-fen%C3%B3meno-de-la (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Doria, L.; Fantacci, L. Evaluating complementary currencies: From the assessment of multiple social qualities to the discovery of a unique monetary sociality. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1291–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Navarro, S. Un mercado financiero floreciente: El del dinero virtual no regulado (Especial atención a los BITCOINS). Rev. CESCO Derecho Consumo 2015, 13, 79–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Casas, G. Las asociaciones de banco de tiempo: Entre la reciprocidad y el mercado. Endoxa Ser. Filosóficas 2002, 15, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrons, A.; Garay, L. An analysis of the process of adopting local digital currencies in support of sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalucía Pueblo a Pueblo—Fichas Municipales Almócita: SIMA. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/sima/ficha.htm?mun=04014 (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Las Pitas. Available online: https://laspitas.wordpress.com/de-que-va-esto/como-funcionamos-con-las-pitas/ (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Váleka, L.; Jašíkováa, V. Time bank and sustainability: The permaculture approach. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 92, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Voz de Almería. Available online: https://www.diariodealmeria.es/almeria/Banco-Tiempo-horas-ayuda-mutua_0_1186081457.html (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Mujer Almería. Available online: http://www.mujeralmeria.es/Area-de-Politicas-de-Igualdad (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Portmann, M.M.; Easterbrook, S.M. PMI: Knowledge elicitation and de bono’s thinking tools. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management, Heidelberg/Kaiserslautern, Germany, 18–22 May 1992; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Suwannatthachote, P.; Bangthamai, E.; Ruangrit, N. Teaching strategies for enhancing creative thinking in virtual learning environments: Guidelines from a survey results. In Proceedings of the 10th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016; pp. 3365–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J. Positive, negative, and interesting: A strategy to teach thinking and promote advocacy. Am. J. Health Educ. 2008, 39, 184–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachsler, H.; Kicken, W.; Van der Klink, M.; Stoyanov, S.; Boshuizen, H.P.; Barach, P. The handover toolbox: A knowledge exchange and training platform for improving patient care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, i114–i120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenciano, J.D.P.; Battistuzzi, M.A.G.; García, J.M.; Márquez, F.J.O.; Toril, J.U. Metodología en el Desarrollo Local Sostenible; Delta Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haque, H.E.; Dhakal, S.; Mostafa, S.M.G. An assessment of opportunities and challenges for cross-border electricity trade for Bangladesh using SWOT-AHP approach. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Tani, A.; Tartiu, V.E.; Imbriani, C. Towards a sustainable forest-based bioeconomy in Italy: Findings from a SWOT analysis. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 110, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S. Social marketing’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT): A commentary. Soc. Mark. Q. 2019, 25, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.I.; Funari, V.; Ferrari, R. Bioleaching for resource recovery from low-grade wastes like fly and bottom ashes from municipal incinerators: A SWOT analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, A.; Cullinane, K. Identifying the main opportunities and challenges from the implementation of a port energy management system: A SWOT/PESTLE analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontyeva, I.A.; Rebrina, F.G.; Sattarova, G.G. Análisis FODA del aprendizaje a distancia en la educación superior. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Valores 2019, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wait, M.; Govender, C. SWOT criteria for the strategic evaluation of work integrated learning projects. Afr. Educ. Rev. 2019, 16, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalustre-Martínez, L.; Moral-Pérez, M.E.D.; Neira-Piñeiro, M.D.R. Teachers’ perception about augmented reality for teaching science in primary education. SWOT analysis. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Cienc. 2019, 16, 3301. [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, M. 5 Lecciones del Fracaso de Japón con las Monedas Sociales, El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/06/14/alterconsumismo/1465885500_146588.html (accessed on 20 May 2018).

- Granados, E.; Rodríguez, R.; Vilachá, L. El desarrollo sostenible como estrategia para abordar la despoblación en el medio rural? Estudio de caso: Almócita. Equidad Desarro. 2018, 1, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, E. La FEMP Alerta: 51 Pueblos de Almería Están en Riesgo de Extinción, La Voz de Almería. Available online: http://www.lavozdealmeria.es/Noticias/122789/2/La-FEMP-alerta:-51-pueblos-de-Almer%-C3%ADa-est%C3%A1n-en-riesgo-de-extinci%-C3%B3n (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Romero, J. Almócita, Capital Española de la Lucha Contra la Despoblación, Cadena Ser. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/emisora/2019/10/03/ser_almeria/1570089130_951715.html (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Kichiji, N.; Nishibe, M. Network analyses of the circulation flow of community currency. Evol. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2008, 4, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reppas, D.; Muschert, G. The potential for community and complementary currencies (CCs) to enhance human aspects of economic exchange. Digithum 2019, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. The Euro, the Pound and the Shell in our pockets: Rationales for complementary currencies in a global economy. New Political Econ. 2000, 5, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Hudon, M. Money and the commons: An investigation of complementary currencies and their ethical implications. JBE 2019, 160, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubels, H.; Bock, B.; Haartsen, T. An evolutionary perspective on experimental local governance arrangements with local governments and residents in Dutch rural areas of depopulation. EPC Politics Space 2019, 37, 1277–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exploring Complementary Currencies in Europe: A Comparative Study of Local Initiatives in Spain and the United Kingdom. Available online: http://www.livinginminca.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Complementary_Currencies.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Bristol Pound is not Making Us Produce Local Products, Say Academics by Ashcroft, E. Available online: https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/bristol-pound-not-making-buy-900512 (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Marshall, A.P.; O’Neill, D.W. The bristol pound: A tool for localisation? Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, F.; Prats, M.A. Why do some areas depopulate? The role of economic factors and local governments. Cities 2020, 97, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaminos, D.; Becerra-Vicario, R.; Fernández-Gámez, M.Á.; Cisneros Ruiz, A.J. Currency crises prediction using deep neural decision trees. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Country | Region | Active | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wära | Germany | Europe | 1931–1931 | It had a value of 1 wära equal to 1 reichsmark. In a community of 500 inhabitants, it managed to generate between 45 and 60 jobs, being the complementary method of payment during its short period of existence. It had its own shop which operated with Wära. After the ban on the currency, the region′s economy was again depressed to pre-war levels [10]. |

| Arbeitswertscheine | Austria | Europe | 1932–1933 | Its value was also 1 arbeitswertscheine was equal to 1 shilling. Its beginning was favored by the City Council of the municipality of Wörgl, and it had some movements of approximately two and a half million shillings. The profits were destined to multiple social projects and it was noticed that while unemployment in Austria rose by 19%, in Wörgl it decreased by 16%. [11]. One year later it was banned by the Oesterreichische Nationalbank, and with it the rates of unpaid bills and unemployment returned to their previous course [12]. |

| WIR | Switzerland | Europe | 1934–present | WIR was founded in 1934 and is referred to nowadays as the WIR-bank. Currently it is a centralized credit system for multilateral exchange, with no physical currency. The WIR system functions as a cashless payment circuit between members and has a value of 1 wir is equal to 1 Swiss franc. It was developed due to the cash shortage of the banks which led to less credit being granted. The WIR system therefore supported small and medium-sized businesses in its early days [12]. Its use became more widespread until personal participation was allowed. The balance sheet of WIR Bank shows roughly CHF/CHW 4 billion (EUR 3,5 billion) [13]. |

| Name | Country | Region | Active | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary Dollar | Canada | North America | 1995–present | The Calgary Dollar is a complementary currency that has experienced several changes. It has recently been re-launched as Canada′s first local and digital currency to be updated. It differs from the crypt coins in that they are not purchased or retired. Users can earn it by placing ads for goods or services they want to sell or exchange through their own online store or through the mobile application [14] |

| Chiemgauer | Germany | Europe | 2003–present | It is a CC that has a total number of users of 3922 and was supported by 561 companies during 2015. This gave the Chiemgauer money an approximate base of EUR 787,000 [15]. |

| BerkShares | United States | North America | 2006–present | BerkShares can be obtained at participating bank branches in exchange for U.S. dollars. The exchange rate is 95 cents to 1 BerkShare. There are about 400 businesses that accept this CC [16]. |

| Brixton Pound | United Kingdom | Europe | 2009–present | This currency is focused on an urban context. It has been designed to maintain and help local exchanges and production in the city. Some 250 companies accept payment via Brixton Pound (B£) [17]. |

| Ora | Orania, South Africa | Africa | 2004–present | The Ora is a complementary currency that offers a 5% discount to buyers. About R400,000 to R580,000 worth of Oras were in circulation by 2011 [18]. They are currently updating the platform to e-Ora which is a digital version of the currency. They are not looking for a direct replacement of the physical currency [19]. |

| Better Bartering credits | Tasmania, Australia | Oceania | 2015–present | It might be the most recent currency (LETS) of those mentioned and has the smallest number of users. This does not imply that they are inactive, as they carry out many events that they advertise through their website. In exchange, 1 Better Bartering (BB) equals AUD 1 or has the commercial value of a AUD 440 service [20]. It draws attention to that difference in exchange price makes services more influential in the community. |

| Virtual Currencies | Local-Territorial-Social Currencies |

|---|---|

| The European Central Bank defines them as “a medium of exchange and a unit of value accepted by a virtual community” [46]. | Facilitate exchanges, satisfy a need, or simply as financial aid. |

| Based on security, integrity, and balance thanks to the protection that has been provided by people who, in exchange for obtaining an advantage / tip, collaborate in the security of the currency by providing algorithm processing. | Based on a principle of development and cooperation, they are currencies that do not have the limitations of legal currencies and that help achieve social and economic ends [47]. |

| Its operation resembles a classic means of exchange with the advantage that payments are made immediately without intermediaries and low transaction costs and exchange is expedited in time. | Their operation is based on trust and reciprocity [48]. They tend to be based on endogenous resources that the formal economy often ignores. |

| Its regulation is more complex since, at first, currencies were classified as “raw materials” [49]. Since then their classification has varied with each country deciding for itself. | There are multiple problems with this type of currency, including temporal, personal, and their impact on the market [50]. They are factors that need to be constantly testes, from the moment of their development to their latter activation. |

| This also leaves them at the mercy of significant fluctuations in their price which can be subject to speculation or be use by other parties [51]. | Currency valuation can vary depending on whether the purpose of the same is to match legal currency or if it is attempting a temporary match. It defining feature is that they cannot be services that are directly exchanged for legal tender such as Time Banks [52]. |

| It is usually obtained through so-called mining, which is broadly based on the resolution of complex algorithms that depend on a previous one. | The LETS are basically non-profit initiatives that attempt to promote the exchange of goods and services in a limited community. |

| All transactions are recorded in a blockchain which is open to everyone. This generates global and transparent exchanges that have a reliability determinant which is deemed to be one their great advantages. Those based on this technology can cause problems if they are analyzed from the environmentally sustainable point of view in contrast to the most basic digital ones [53]. | For its development, an entity is usually created to maintain an operational record. This records in detail all the operations carried out or pending credits. These usually take the form of exchange or barter of minor short-term services separate from their usual provision of professional services. |

| Can be used at any time. | It is particularly used if the legal economy is paralyzed and its reactivation is complex. |

| Positive | Negative | Interesting |

|---|---|---|

| 1. A general increase in purchasing power. 2. Simplicity of payments, similar to using legal tender. 3. Promotion of social projects. 4. The endogenous economy is motivated and supports job creation. 5. They support normal monetary infrastructure. 6. They are an additional source of income. 7. Strengthens relational ties. 8. It is difficult to suffer from oversupply and cause inflation. 9. It is based on the original idea of money. 10. In principle, it retains and keeps wealth within the area. 11. Promote an idea of honesty and trust. 12. In its most recent implementation, it favors equality as all draw from equal conditions. 13. It promotes social justice, equality and the rest of the values that it aims to protect. | 1. The monetary system is made more complicated due to additional payment options. 2. User may be faced by additional commissions or fees. 3. Training is required to use the currency. 4. The number of users is very limited, and its use is very localized. 5. The massification of some currencies in particular can undermine them. 6. The high cost of developing the currency. 7. High level of volatility of some types such as virtual currencies. 8. The ease with which they can be counterfeited. 9. If they are not based on the needs of the people. | 1. Analyze nearby municipalities to see their point of view and see if there is interest in participating. 2. Check social acceptance. 3. Study how the proposed new economic approach can help in the repopulation of the area. 4. It could be taken as a reference municipality. 5. Carry out analyses that show the increase in general well-being. |

| Local 1 | Local 2 | Local 3 | Local 4 | Local 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keep | Lack of work | Lack of interest in the town | An ageing population | Environmental Problems | Lack of varied work |

| Failures | Maintaining population levels | An ageing population | Maintaining population levels | The development of interesting activities, but that were only temporary | Maintaining population levels |

| Concerns | An ageing population in the town | Maintaining population levels | More populous neighboring town centers | Loss of heritage | School closures |

| Competitors | Economically stronger and larger neighboring municipalities | Economically stronger and larger neighboring municipalities | The capital city | Neighboring provincial centers | The capital city |

| Opportunities | Local Festivals | Natural Resources and Local Festivals | Natural Resources | Natural Resources and Local Festivals | Initiatives of the Local Council |

| Business Person 1 | Business Person 2 | Business Person 3 | Non-Resident 1 | Non-Resident 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threats | Lack of varied work | Ageing population | Average age of townspeople | Better situated towns with better access | Other competitors in same business activity |

| Failures | Population | Measures taken to combat depopulation | Population | “Always seeing the same people” | Badly developed policies |

| Concerns | Ageing population | Maintaining population levels | Average age of townspeople | Sale of their property in the area | Loss of a second job in the municipality |

| Competitors | The capital city and nearby coastal areas | The capital city | The capital city | Municipalities located in Sierra Nevada but with better facilities | Municipalities closer to the coast |

| Opportunities | A Local Council and Associations with Initiatives | Good social relationships | Initiatives promoted by the Local Council | Nearby hunting preserves | Local Festivals |

| 2006 | 2011 | 2018 | Population Change Between 2006 and 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almócita | 156 | 191 | 172 | 10% |

| Beires | 128 | 118 | 114 | −10% |

| Dalías | 3807 | 3991 | 3978 | 4% |

| Fondón | 950 | 976 | 1017 | 7% |

| Padules | 523 | 510 | 449 | −14% |

| Final Budgeted Income | 451,862 |

| Final Budgeted Expenses | 450,083 |

| Income by Inhabitant | 2611 |

| Expenses by Inhabitant | 2601 |

| Number of Tax Returns | 56 |

| Employment Income Tax | 268,774 |

| Actual Net Taxable Income | 7771 |

| Estimated Net Taxable Income | 6155 |

| Other Types of Income | 26,538 |

| Average Net Taxable Income | 5522 |

| Weaknesses | Threats |

|---|---|

| Aged population Lack of financial resources Lack of entrepreneurial culture Lack of services in the area and difficulty in maintaining existing ones Lack of financial subsidies to carry out activities Apathy and lack of motivation among young people: desire to leave Unused resources Scarcity of variety in tourist offer Initial negative reactions to mention of a new currency | Excessive bureaucracy Lack of generational replacement Limited employment Climate change and desertification Rural exodus Disinformation and lack of recognition of the area Lack of public or private economic resources Political changes Rejection of abrupt economic changes |

| Strengths | Opportunities |

| General climatology Rise of environmental awareness Heritage Existence of the Natural Preserve and National Park of Sierra Nevada Quality of life Programs initiated by the Local Council Participatory and active women Eagerness to excel Excellent local environmental awareness Assimilation of environmental awareness Innovative spirit that assimilates the proposals and participates in them | Increased awareness of the natural product consumption. Promotion and campaigns with a more human touch that create greater social sensitivity. Local Council support for the development of a local currency. Rural development programs with justifiable outlay. Boom of Themed tourism based on the social and environmental factors as an extra source of income. Improvement of the economic situation focused the ecological and tourist factors while stimulating the economy using social currencies. Ability to attract new residents who share same values. Retain the existing population through the use of an exclusive currency in the area. |

| Weaknesses | Threats | Strengths | Opportunities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ageing Population | 1. Rural Exodus | 1. Heritage | 1. Promotions and Campaign | |

| 2. High economic costs | 2. Employment | 2. Citizen Engagement | 2. Exclusivity | |

| 3. Initial negative reactions | 3. Disinformation | 3.Institutional Support | 3.Economic recovery | |

| Cost | D1–D2–D3 Unprofitable and unaffordable costs | A2–A3 Alternative, non-competing payment methods | F1 Possible private barter | O2–O3 Increased purchasing power |

| Local Support | D1–D2–D3 Lack of support without explanation or demonstrable interest | A3 Lack of acceptance | F1–F2–F3 Promotion of the feeling of “belonging” to the town | O1–O3 High levels of participation as long as there is a perceived common benefit |

| Labor Force | D1 Need of re-population | A1 Lack of human resources | F2 Participation in activities | O2–O3 New ways to prosper economically and support the existing economy |

| Municipal Plan: Development of Complementary Currency | D1–D2–D3 There is currently no assigned market | A1–A3 Lack of population that supports the plan | F1–F2–F3 Greater value placed on “local” | O1–O2–O3 In general terms, it improves the municipality |

| Objective 1: Development of Social and Environmental Campaigns. | Objective 2: Development of a Social Currency. |

|---|---|

| Provide greater social awareness Explain the possible approaches for economic development Approach and attract new participatory residents Highlight existing institutional support | Investigate and explore additional objectives in creative meetings Unite local environmental awareness philosophy Sample the situation after its development Be a pioneer in social thought |

| Location | Almócita |

|---|---|

| Objective | Assess the viability of a social currency through a multi-level analysis |

| Innovation | Use a different tool as a way to analyze local development in the area |

| Insights | Establishment of a local development approach that could be extrapolated to surrounding areas |

| Expected Impact | Improve the health of the municipality in general: from economic to cultural strengthening |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Corral, F.J.; de Pablo-Valenciano, J.; Milán-García, J.; Cordero-García, J.A. Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145672

García-Corral FJ, de Pablo-Valenciano J, Milán-García J, Cordero-García JA. Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145672

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Corral, Francisco Javier, Jaime de Pablo-Valenciano, Juan Milán-García, and José Antonio Cordero-García. 2020. "Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145672

APA StyleGarcía-Corral, F. J., de Pablo-Valenciano, J., Milán-García, J., & Cordero-García, J. A. (2020). Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles. Sustainability, 12(14), 5672. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145672