1. Introduction

Horses have played very important roles in Chinese history and culture. With the exception of the mythical dragon, horses are probably the most important and recurrent animal in Chinese culture, often acting as a symbol of speed, courage, integrity, diligence, perseverance, power, energy, leadership, and success [

1,

2,

3]. In addition to their contributions to transportation and farming, horses were also an important part of China’s military force and a determining factor of many changes in the country’s territories and borders. For example, the Great Wall was built to protect and consolidate territories of Chinese states and empires against various nomadic warriors on horseback from the north. The important role of horses in Chinese history and culture is well summarized by Creel [

1]: “China’s foreign relations, military policy, economic well-being, and indeed its very existence as an independent state were importantly conditioned by the horse.”

While the role of horses in Chinese history and their cultural influence in some other areas have been well documented in the literature [

1,

2,

3], this study examines the development and trends of China’s equine industries since 1949. The term industries rather than industry is used because of the different ways horses are employed, viewed, and treated across sub-sectors such as farming, transportation, sports, recreation, and equine-assisted therapy [

4]. According to the database of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations for 1961–2017 [

5] and China’s statistical yearbooks published by the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBSC) [

6], China had the highest number of horses in the world from 1961 to 2004 (and likely some years prior to 1961, though there are no data to confirm it). However, China’s horse population has dropped significantly and steadily since its market-oriented economic transition, started in the late 1970s, from 11.50 million in 1978 to only 3.47 million in 2018 [

6]. The dramatic changes in China’s horse population since 1961 are unique when compared with those of other major horse nations. For example, the United States has experienced a significant and steady increase in its horse population since the mid-1960s and has been the world’s largest horse nation since 2004 [

5]. One interesting question is whether income and economic growth in the United States is a contributing factor of the steady increase in its horse population since the early 1960s and, if so, why the rapid income and economic growth in China since the late 1970s has likely contributed to the steady decline in its horse population.

China’s equine industries have experienced significant changes since the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, especially since the market-oriented economic transition started in 1978, but there are few studies on China’s equine industries in the literature. Our review of the literature in both English and Chinese suggests that, except for a few studies on the role of horses in Chinese history and culture [

1,

2,

3] and some veterinary studies, there are extremely limited socioeconomic studies on China’s equine industries. As China was the largest horse country from 1961 to 2004 and dropped to the fifth largest horse nation in 2017, according to FAO and NBSC data [

5,

6], there are many interesting but unanswered questions about China’s equine industries. What are the major factors for the dramatic decline in China’s horse population since 1978? Have there been any significant changes in the regional distribution of the horse population in China? What are the challenges and opportunities for the equine industries in China’s transitional economy? How are China’s equine industries linked to the rest of the world through trade and other activities like sports and tourism?

The major objectives of this study are to review the development of China’s equine industries since 1949, identify major factors contributing to the steady decline in its horse population since 1978, and discuss the challenges and opportunities for the horse industries’ development. Specifically, the most recently available data from FAO and NBSC are used to assess the national trends and regional distributions of China’s horse population through a graphical analysis, and to identify the major factors behind the steady decline in China’s horse population and quantify their impacts through a regression analysis. While equine industries and their roles in the local economy, climate change, and sustainable development have received more attention in recent years [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], this study contributes to the literature by addressing several research questions about the equine industries in China, a large equine nation but understudied in the equine literature. This paper is organized into five sections: Following this introduction,

Section 2 introduces the data and methods,

Section 3 presents the empirical results,

Section 4 discusses the challenges and opportunities for China’s equine industries, and

Section 5 summarizes the major conclusions.

2. Data and Methods

The data used in this study are from four sources: (a) FAO’s online database (FAOSTAT), that includes horse population, exports, and imports for China and many other nations from 1961 to 2017; (b) China’s statistical yearbooks, published by NBSC, that include China’s total horse population from 1949 to 1965 and from 1970 to 2018, as well as the horse population by province from 1978 to 2018; (c) media reports, newspapers, two popular equestrian magazines in China (Horsemanship and World Horsemanship), government publications, etc.; and (d) China’s agricultural yearbooks, population yearbooks, and other yearbooks published by different Chinese government agencies.

While China has 23 provinces, four municipalities, five autonomous regions, and two special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macao), this study does not include Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao due to data limitation. Furthermore, all the provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions are referred to as provinces in this paper.

There are three differences in China’s horse population data from FAO and NBSC: First, while the horse population from NBSC is specified as the end-of-year data, FAO data are the beginning-of-year data, although this is not specified by FAO. When the FAO data are adjusted by one year, they are almost 100% consistent with the NBSC data. Second, China’s horse population from 1966 to 1969 is not available in NBSC data but is available in the FAO database and was likely estimated by FAO. Third, NBSC adjusted China’s annual horse population from 2006 to 2016 to a lower level in China’s statistical yearbooks published in 2018 and 2019, without any explanation. As a result, the data from NBSC are significantly lower than those from FAO for 2006 to 2016. While China has a well-established statistical reporting system, with almost every village and community accounted for by NBSC, data on China’s horse population are likely to be more accurate and consistent than those from many other developing nations. The number of horses is reported in the same way as that of hogs, cows, goats, camels, and other large animals in China [

6].

Data from the above sources are used to attain the research objectives through a graphical analysis and a regression analysis. Specifically, the national data are used to assess the national development and trends through a graphical analysis, while the regional data from 1978 to 2018 are used to examine the changes in the regional distribution through graphs and GIS maps, and the panel data by province from 1993 to 2018 are used to identify the factors contributing to the decline in horse population and quantify their impacts through the following regression model:

where

Y is the horse population,

PD is the population density,

UP is the proportion of urban population,

SP is the share of the primary (agricultural) industry in the GDP,

MP is the total machine power in the agricultural sector,

CA is the number of cars,

AR is a dummy variable for the autonomous regions,

BR is a dummy variable for the provinces that border other nations on land,

e is the error term,

i denotes regions,

t denotes years, and

a,

b,

c,

d,

g,

h,

j, and

k are the coefficients to be estimated.

The estimation results of this model will provide information on the significance of each independent variable as well as its marginal impact on the dependent variable with other variables controlled. Summary statistics of the dependent and independent variables and the estimation methods for the regression model will be presented together with the estimation results in the following section. Some econometric issues associated with panel data, such as fixed-effect model vs. random-effect model, will also be discussed.

3. Empirical Results

This section presents the empirical results in three subsections: (1) development and trends of China’s horse population since 1949, (2) changes in the regional distribution of horse population in China since 1978, and (3) results of the regression analysis.

3.1. Development and Trends of China’s Horse Population since 1949

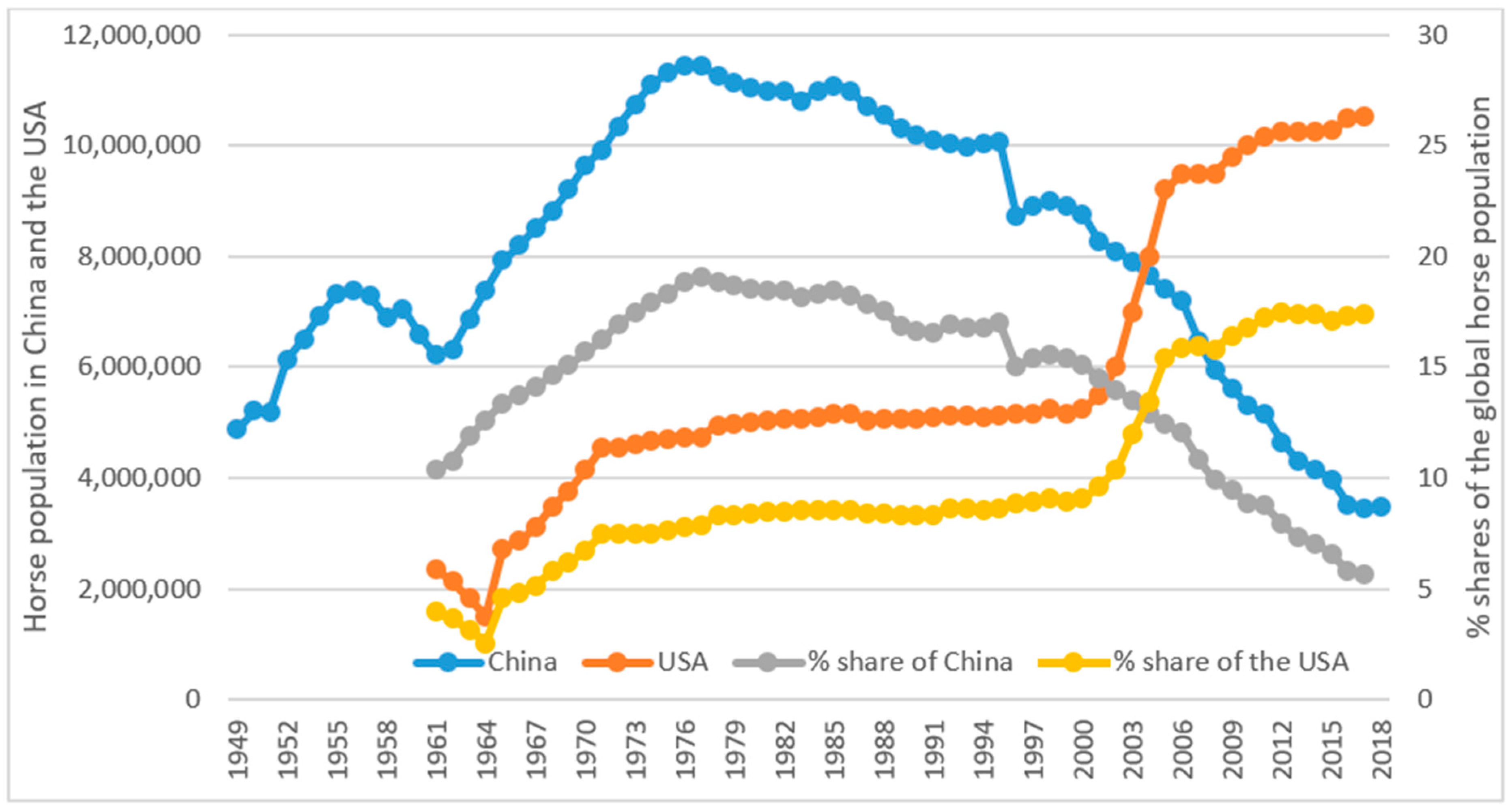

Although horses have been raised in China for thousands of years, annual data on the country’s horse population are only available since 1949. China’s horse population from 1949 to 2018 and its percentage share of the global horse population from 1961 to 2017 are presented in

Figure 1. For comparison purposes, the horse population of the United States and its percentage share of the global horse population from 1961 to 2017 are also presented in

Figure 1. The United States had only about 2.0 million horses in the early 1960s but has experienced a significant and steady increase in its horse population since the mid-1960s, from 2.8 million in 1965 to 11.2 million in 2017. The United States surpassed China in 2004 and has been the largest horse nation in the world ever since [

5].

A review of the changes in China’s horse population and its agricultural development since 1949 suggests that the changes in China’s horse population were closely related to its agricultural and rural development and can be divided into four periods. First, following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the central government published the Land Reform Law in June 1950, abrogating ownership of land by landlords [

13,

14,

15]. As a result of the land reform, land was confiscated from former landlords and redistributed among landless peasants and the landlords themselves, who now had to till the land to earn a living. Around 300 million peasants who had little or no land for generations were assigned some 47 million hectares of land plus farm implements, livestock, and buildings. The peasants were also relieved of rent payments equivalent to 35 billion kilograms of grain per year. The feudal system of land ownership that had existed for more than 2000 years in China was completely destroyed and the landlord class was eliminated [

13,

14,

15]. China’s land reform significantly liberated productive forces and increased the productivity of agriculture. While some peasants received horses and other livestock from the landlords for free, others also made efforts to purchase horses for transportation and farming purposes. As a result, China’s horse population increased from 4.88 million in 1949 to 7.37 million in 1956. The increase in the horse population during this period contributed significantly to the rapid increase in agricultural production.

Second, the central government started the collectivization movement in rural China in the mid-1950s in order to overcome the limitations of small-scale household production and to achieve the economies of scale in agricultural investment and production, especially in irrigation and land improvement projects [

16]. Peasants were first organized into collaborative groups in the mid-1950s and then into large people’s communes in 1958. The private land ownership from the land reform around 1950 was replaced with collective land ownership, under which production and distribution were organized collectively by villages. In the late 1950s, China also started the “Great Leap Forward” to increase its production of steel and other industrial products. A large percentage of rural laborers were politically forced to participate in such production, with very low productivity and efficiency. Together with some major natural disasters, the Great Leap Forward movement caused significant food shortage and famine from 1958 to 1961. As the small-scale farm production by individual households was replaced by larger-scale production by villages, the demand for horses was reduced significantly and, as a result, China’s horse population dropped from 7.37 million in 1956 to 6.21 million in 1961.

Third, recognizing the Great Leap Forward’s damages to the national economy, the Chinese government implemented a set of policies to increase agricultural production in the early 1960s, but many such policies were interrupted by the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976. The data from FAO and NBSC show that China’s horse population increased significantly and steadily from 1961 to 1977 and reached the record high of 11.44 million in 1977. Although the accuracy of data for the Cultural Revolution period has been questioned by some researchers, there are no other data available to assess the data problems for the period. One major reason for the steady increase in horse population over this period was the slow progress in both agricultural mechanization and the improvement in rural transportation and, as a result, horses were raised to power many farming and transportation activities in rural China, especially in the areas with no roads for automobiles and tractors.

Fourth, China’s market-oriented economic reform and transition started in rural areas in 1978. The communes were gradually replaced by the household production responsibility system from 1978 to 1985 [

17]. Under the new system, the collectively-owned land was contracted to individual households, and such simple institutional change greatly improved the incentives of peasants and resulted in dramatic increases in farm outputs and income. The decollectivization was found to improve the total productivity and to account for about 50% of the output growth in Chinese agriculture during 1978–1984 [

17].

Different from the previous periods, the increase in farm production and rural income did not result in an increase in the demand for horses because of the increased availability of farm machine like tractors as well as the improvements in roads and transportation in rural areas. As shown in

Figure 1, China’s horse population has declined significantly and steadily since 1978, from 11.50 million in 1978 to only 3.47 million in 2018. The factors contributing to the steady decline in China’s horse population since 1978 and their specific impacts will be analyzed through regression analysis in a later subsection.

3.2. Changes in the Regional Distribution of Horse Population in China since 1978

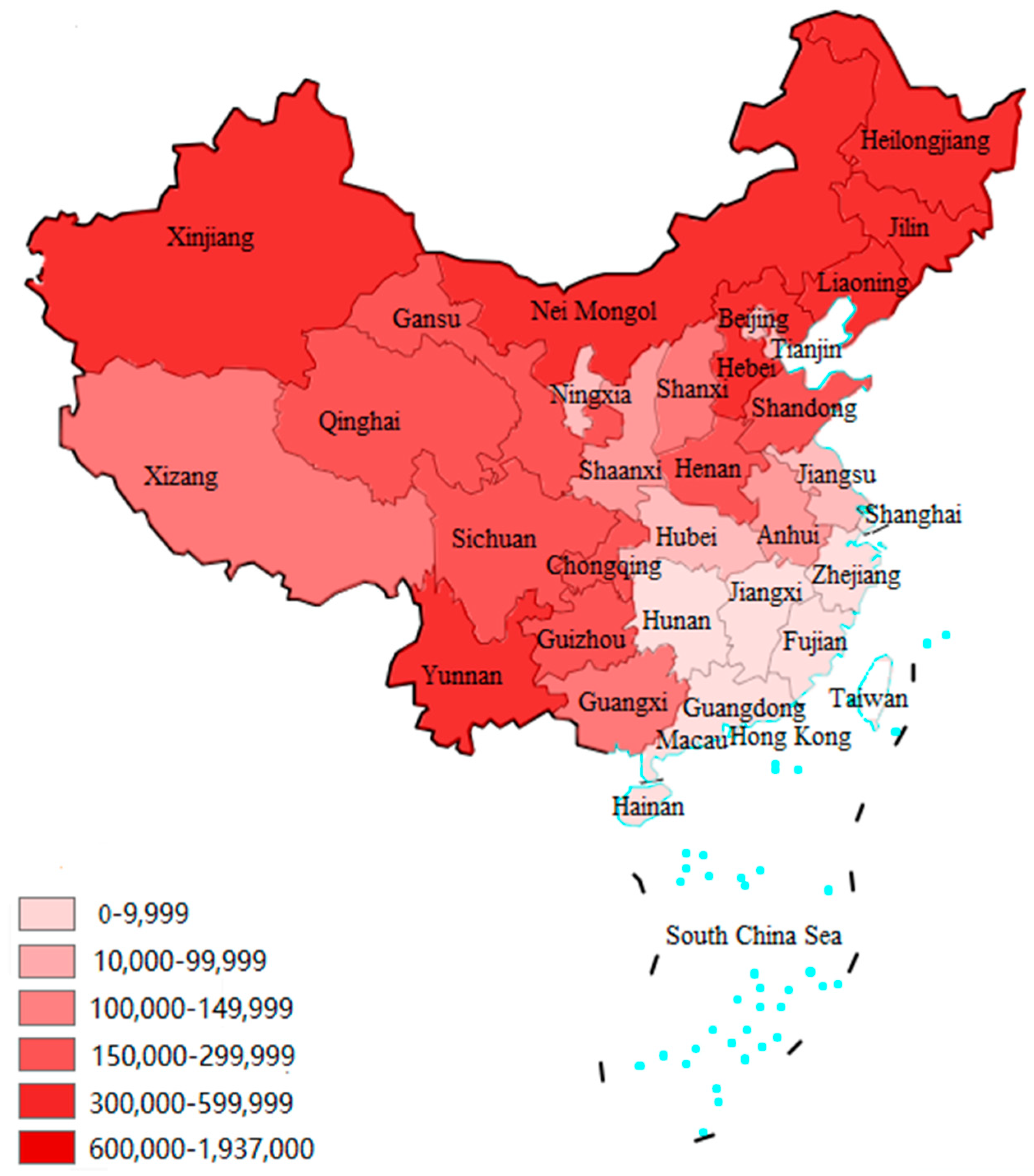

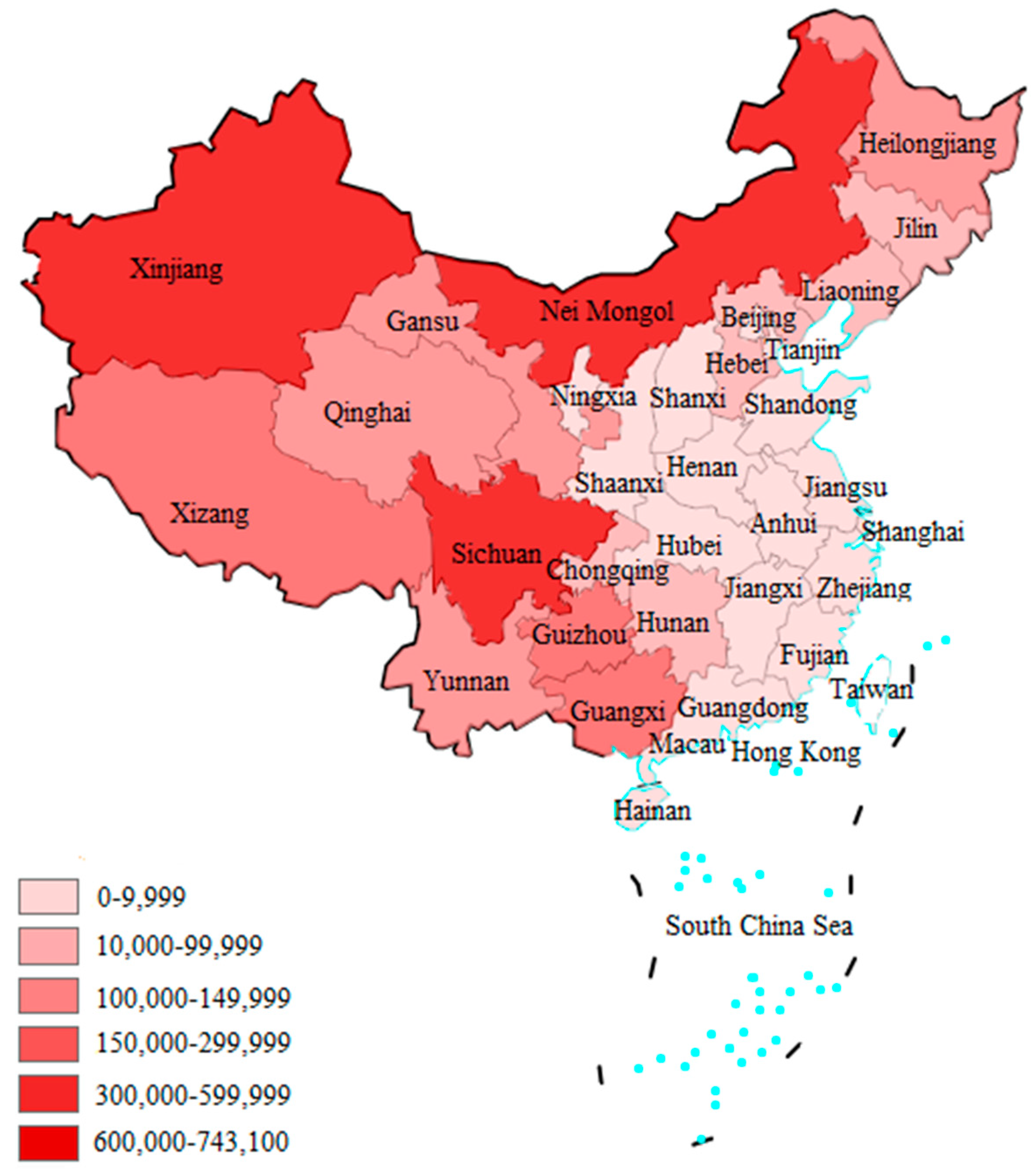

While China’s total horse population has declined significantly and steadily since 1978, it is interesting to examine the changes in regional distributions, as China is a vast nation and there are significant differences across regions. This paper examines the changes in horse distribution across provinces in China since 1978 through GIS and graphical analyses. The data presented in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 suggest three major findings: First, as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, seven provinces had 600,000 or more horses each in 1978, and they were concentrated in northeast China (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning) and north China (Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia or Nei Mongol) plus Hebei and Yunnan, but only three provinces had 600,000 or more horses in 2018 (Sichuan, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia). For the provinces with 300,000 to 599,999 horses, the number dropped from six (Shandong, Henan, Qinghai, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Tibet or Xizang) in 1978 to zero in 2018. A comparison of

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 also suggests that the three northeastern provinces (Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning) experienced the greatest decrease in the horse population. For example, the horse population in Heilongjiang, a large agricultural province, dropped from 1.94 million in 1978 to 0.13 million in 2018.

Second, Sichuan is the only province that experienced a significant increase in the horse population, from 0.31 million in 1978 to 0.74 million in 2018. An examination of the horse distribution among the 21 prefectural level cities and prefectures in Sichuan, available in Sichuan Statistical Yearbooks, indicates that the horse population inside the province is largely concentrated in the three ethnic autonomous prefectures (Ganzi Tibetan nationality, Aba Qiang nationality, and Liangshan Yi nationality autonomous prefectures) in the western Sichuan province that have a very high percentage of ethnic population and low population density. For example, in 2017, the three autonomous prefectures accounted for 94.10% of the province’s horse population of 0.72 million but only 8.49% of the province’s total population of 83.02 million [

18].

Third, China’s horse population has increasingly concentrated in Sichuan, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Tibet. Although Tibet’s total horse population ranked number 13 in 1978 and number 5 in 2018, there are two unique characteristics. First, its horse population has been relatively stable as compared to that of other provinces in China, increasing from 0.22 million in 1978 to 0.43 million in 2003 and then dropping back to 0.28 million in 2018. Second, due to its sparse human population, Tibet is among the top provinces in terms of number of horses per million people.

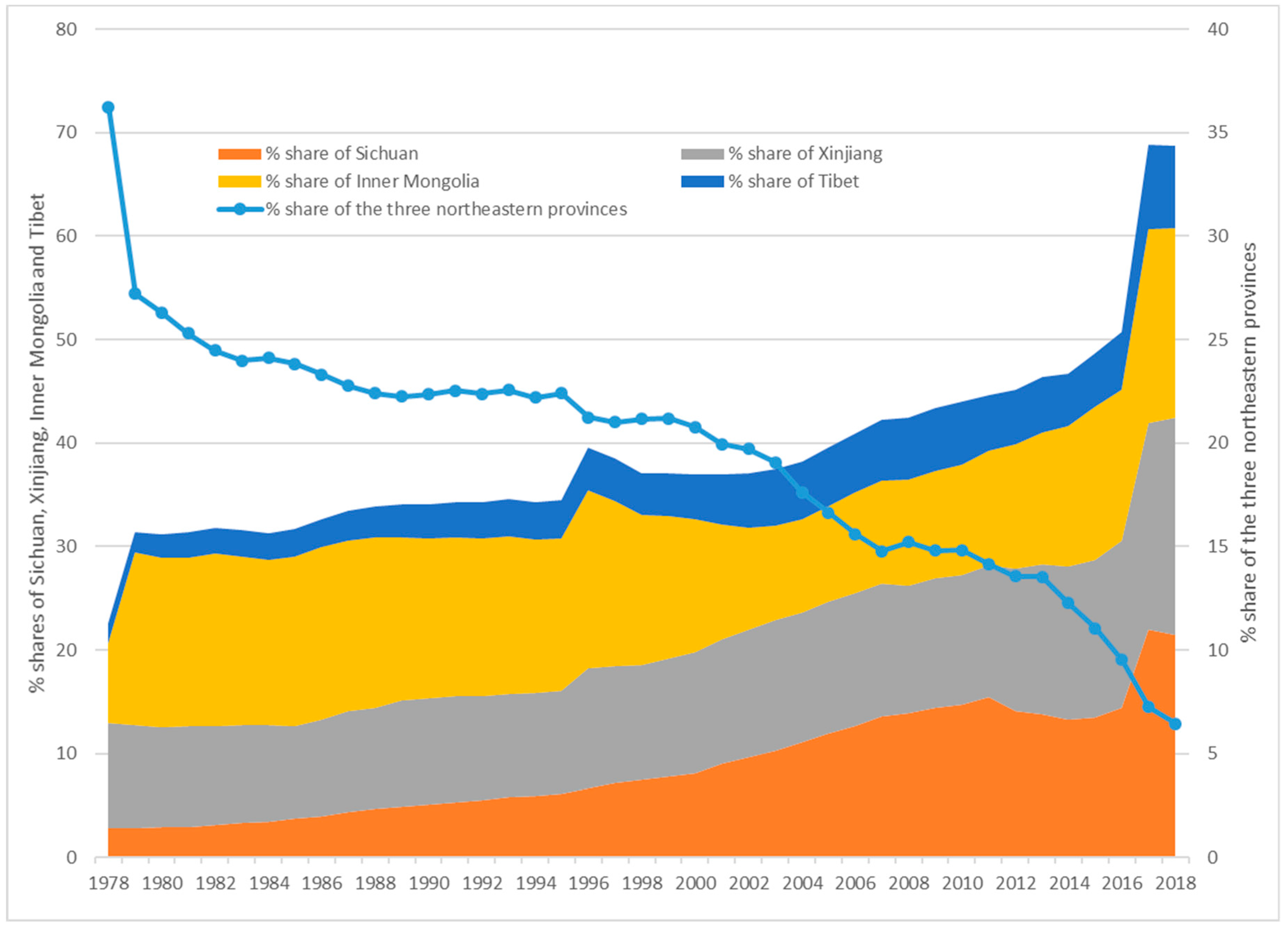

As shown in

Figure 4, the above four provinces’ percentage shares of China’s total horse population increased steadily and significantly from 1978 to 2018, reaching a total of 68.0% in 2018. On the other hand, the overall percentage share of the three provinces in the northeast (Heilongjiang, Liaoning, and Jilin) dropped steadily from 36.5% to 6.5% over the same period. Considering that China’s horse population is highly concentrated in the three ethnic autonomous prefectures in the western section of the Sichuan province and the three autonomous regions (Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Tibet), it seems clear that China’s horse population has been increasingly concentrated in the above autonomous regions of ethnic nationalities that have the tradition of having horses in their cultural, religious, sport, and economic activities.

3.3. Results of a Regression Analysis

Although our panel dataset includes 31 provinces over 26 years (1993–2018), data from only 24 of the provinces are used to estimate the regression model introduced in a previous section for two reasons: First, five provinces (Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Shanghai, Guangdong, and Hainan) were dropped from the dataset because their horse population was zero or very close to zero over the study period. Second, Chongqing, which separated from the Sichuan province and became a municipality in 1995, was combined with Sichuan in this analysis. The panel data on horse population, together with the explanatory (independent) variables specified in the regression model presented in

Section 2, were used to estimate the regression model. Summary statistics of the dependent and independent variables are reported in

Table 1. Similar panel datasets from China have been used in many previous studies [

17,

19,

20].

For the panel data with both cross-province and over-time variations, different statistical tests were conducted to compare alternative models for the dataset. First, F tests were performed to assess whether there were significant fixed effects across provinces and/or over time. The test results suggest that there was no significant fixed effect over the study period of 25 years, but there were significant fixed effects across some provinces. According to the test results, a model with fixed provincial effects was estimated and is reported in the second column of

Table 2. As fixed-effect models and random-effect models are often applied to panel datasets [

19,

20], a random-effect model with seven explanatory variables was estimated and is reported in the third column in

Table 2.

Second, a Hausman test was conducted, and the test result suggests that the model with random effects performs better than the fixed-effect model for the dataset. The following discussion of the estimation results focuses on the random-effect model, although the estimation results from the two models are pretty consistent.

The estimated random-effect model suggests three major conclusions: First, the R2 and Wald-statistic suggest that the estimated random-effect model fits the data reasonably well, explaining 35.16% of the variation in the horse population, and the estimated model is significant at the 0.01 significance level. Second, the percentage of the urban population, the total agricultural machinery power, and the number of cars had negative and highly significant impacts on the horse population when other independent variables included in the model were controlled. Such impacts are very consistent with the discussion about the national trends and regional distribution of China’s horse population reported in the previous subsection. Third, the agricultural sector’s percentage share of GDP and the two dummy variables for autonomous regions and provinces that border other nations on land showed positive and significant impacts on the horse population when other explanatory variables were controlled, suggesting that agricultural regions, the provinces that border other nations on land, and the autonomous regions tend to have more horses when other variables are controlled. The significantly higher value of R2 for the random-effect model than the fixed-effect model also confirms the result of the Hausman test, indicating that the random-effect model fits the dataset better than the fixed-effect model.

Although our regression analysis is limited by the data availability, this paper presents the first or one of the first econometric studies on the changes in China’s horse population, and quantitatively confirms some conclusions derived from the graphical analysis reported in the previous subsections.

4. Challenges and Opportunities for China’s Equine Industries

This section discusses the challenges and opportunities for China’s equine industries. As analyzed in the previous sections, China’s agricultural mechanization, steady decrease in the agricultural sector’s share in China’s GDP, improvement in rural transportation with more tractors, trucks, cars and motorcycles, urbanization, and the decreased land availability for and the lack of economic returns from horses are the major factors contributing to the steady decline in China’s horse population since 1978. All of the above factors will likely continue to reduce China’s horse population in the coming years, especially in the provinces in the central, southeast, and east regions with significantly higher population density and land increasingly being used for housing and industrial development. China’s horse population is likely to be more concentrated in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and the western Sichuan province, which have relatively low population density and high proportion of minority ethnic population with the tradition of horses in their cultural, religious, sport, and economic activities.

Based on the changes in horse population in the United States and its potential correlation with economic development cycles, Linklater [

21] predicted that “China’s horses will cease their decline and eventually grow in number again as its more affluent communities rediscover their equestrian traditions and culture.” The findings from our analysis, presented above, suggest that Linklater’s prediction may happen in some communities in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and the western Sichuan province, but the horse industries are unlikely to resurge in other regions in China for at least two reasons. First, the growth in the horse population in the United States since the mid-1960s has mainly been due to the increase in horse ownership of individual households with available land. In contrast, In contrast, land for horses is not available for most households in China. Also, the land scarcity in China will likely continue to increase, making it impossible for individual households to have horses, except for some regions in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and the western Sichuan province.

Second, the increasing horse ownership in the United States is mainly for leisure and recreation purposes, not for the purpose of income. China’s situation is very different from that of the United States. People who live in rural areas, especially in rural areas with potential land available for horses, generally have significantly lower income and cannot afford to support horses with limited economic revenue. On the other hand, people with high income and desire to own horses generally live in cities, where it is simply not feasible for them to own horses either. It is the prediction of this study that all the factors that have contributed to the decline in China’s horse population since 1978 will likely continue to reduce China’s total horse population in the coming decade. The experience of the United States and China suggests that economic and income growth may contribute to the growth in equine industries in some nations or regions, but that may not be the case in many other nations or regions.

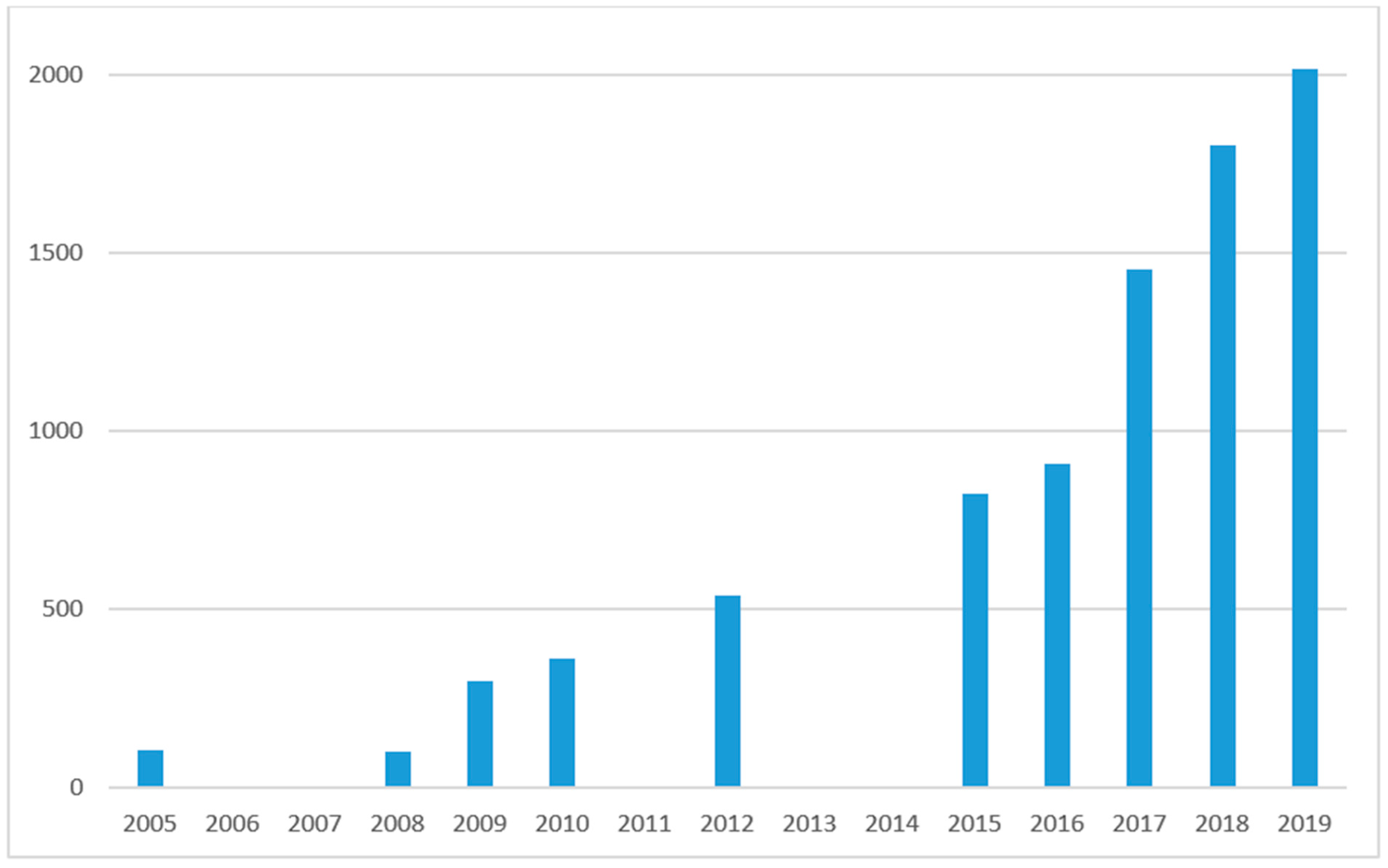

There are at least four unique opportunities for the development of China’s equine industries in certain regions. First, although equestrian sports and recreation in China were minimal until the early 2000s, they have developed rapidly in the past decade. Since China participated in the equestrian events for the first time in the 2008 Olympic Games, equestrian sports and shows have become more popular in China, where horses play an important part in history and culture. For example, as shown in

Figure 5, the number of equestrian clubs in China has increased steadily and significantly since the mid-2000s, from 107 in 2005 to 2000 in 2019 [

22]. These clubs have offered membership and organized many events, especially in large cities like Beijing and Shanghai. For example, the equestrian clubs generated an estimated total revenue of 9.24 billion RMB in 2017 and likely around 12 billion RMB in 2018 [

22]. A study in the United States found that almost 42% of the economic activity generated per horse at equestrian events in the area remained within the community [

8]. While it is infeasible for most individual Chinese households to own horses, especially in cities and relatively developed regions with extremely limited land, equestrian clubs are a way for many urban households to enjoy equestrian events and activities, while contributing to the area’s economic development.

In addition to the equestrian clubs, many companies and organizations have also made investments in efforts to enhance the development of equestrian activities and marketable products. For example, China hosted more than 80 international and national equestrian shows and events in 2018 [

22]. Moreover, while equestrian clubs, sports, and shows in Hong Kong and Macao are more developed than those in most of the areas in mainland China, the increasing collaboration between mainland China and Hong Kong and Macao as two special administrative areas will be helpful for the development of equine activities and events in mainland China [

23].

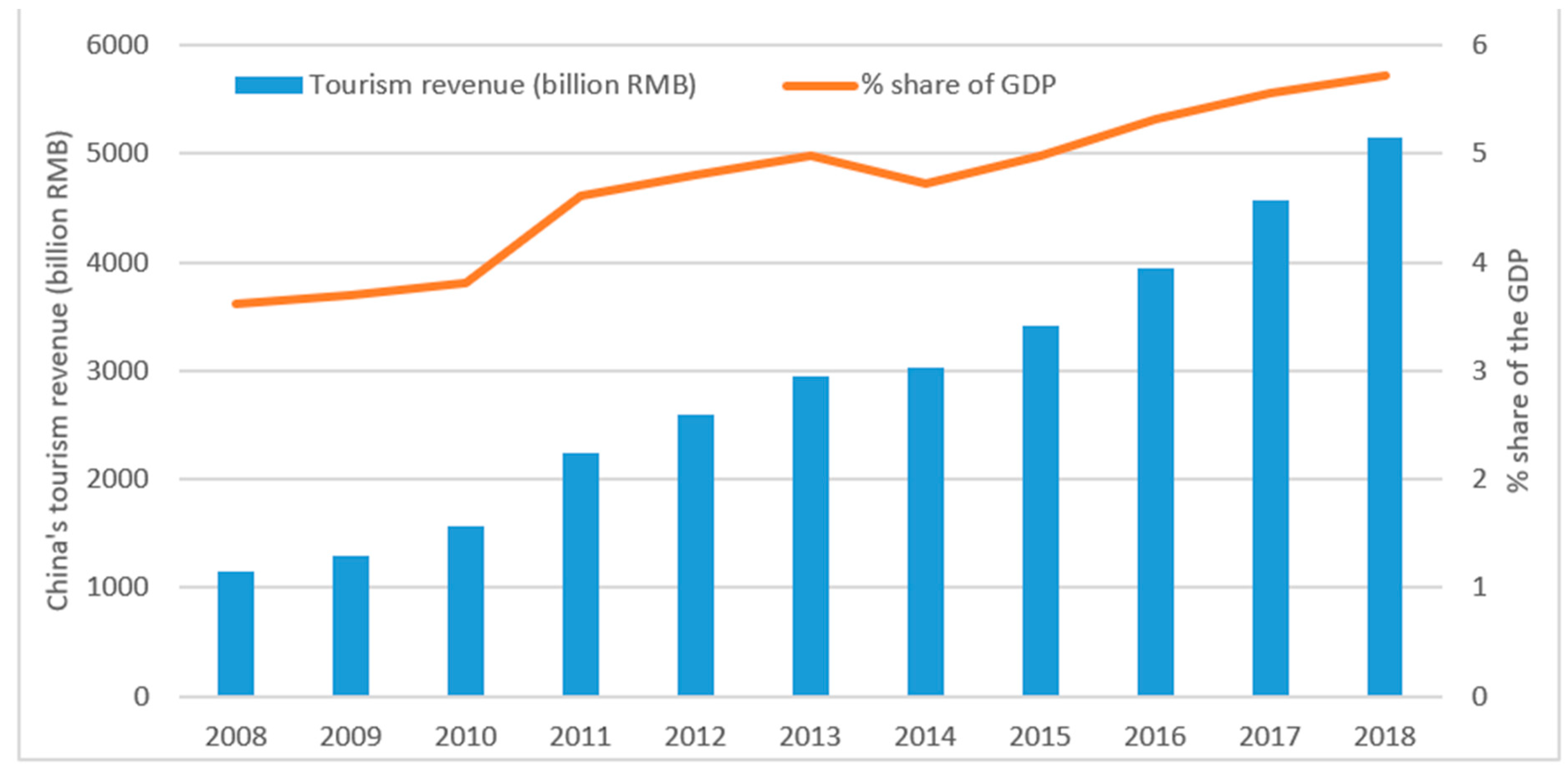

Second, China’s rapidly developing tourism industry will continue to provide opportunities for its equine industries. As shown in

Figure 6, China’s revenue from tourism increased from 1155 billion RMB in 2008 to 5150 billion RMB in 2018, and its share in the GDP increased from 3.63% to 5.73% over the same period, suggesting that the revenue from tourism grew at a significantly higher rate than the GDP [

6]. The equine industries have benefited from, and contributed to, the development of the tourism sector. Previous studies have suggested that the introduction of equine tourism can provide economic opportunities for small farms, contribute to sustainable development in rural areas, and protect cultural heritage [

8,

9,

11,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. In China, an increasing number of people have traveled to Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and the western Sichuan province to experience and enjoy horse-related activities in recent years, and such activities will continue to provide revenue for the equine industries in such regions. China’s entertainment industry has also developed rapidly in the past two decades and constructed many TV and movie studios or parks (such as the Hengdian World Studio in the Zhejiang province and Shanghai Movie Park in Shanghai), and horses are generally a major part of such projects. Many of the studios and parks have become famous tourist sites for visitors to watch battlefields with soldiers on horseback. Furthermore, many areas and communities in the major horse provinces, like Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, have invested in horse-related tourist projects, and such investment will continue to provide opportunities for the equine industries [

30,

31].

Third, the market for horse-related food, sport, and other products, like horse milk, has expanded quickly in recent years, and the expansion of such markets will continue to provide opportunities for the equine industries. For example, horse milk is considered to have many health benefits and is sold at 40 RMB or about

$6 per kilogram in Inner Mongolia [

30]. There are also significant niche markets for other horse products, including glue made from horse hooves, and violin bows and paintbrushes made from horsehair in China and around the world.

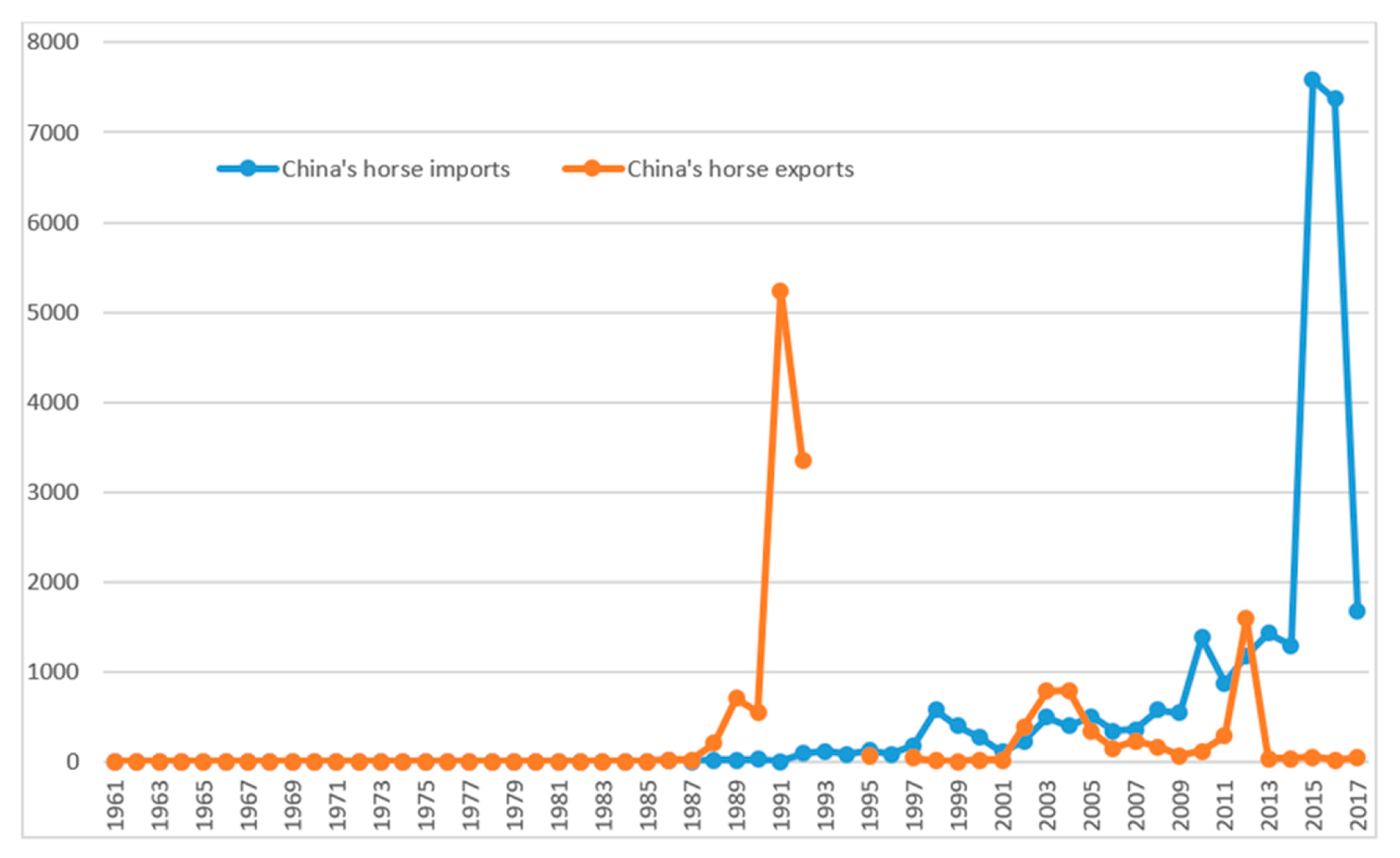

Fourth, the international market may also provide opportunities for China’s equine industries. FAO data on China’s horse exports and imports from 1961 to 2017, presented in

Figure 7, suggest that China’s annual horse exports have been under 1000 since 1961 (except for 1991, 1992, and 2012). In contrast, China’s horse imports have increased significantly since the early 2000s. The increase in China’s horse imports in recent years was mainly to meet the demand of the growing equestrian clubs and sport teams. For example, China imported about 2000 horses from the Netherlands, New Zealand, Mongolia, and others in 2018, and the imported horses were mainly for equestrian clubs [

22].

As the economic and cultural exchange and collaboration between China and other nations continue to increase, many horse-related activities such as horse-assisted therapy and pregnant mare urine (PMU) for pharmaceutical products and medical treatments will likely be introduced to China and provide additional opportunities for China’s equine industries [

4,

32,

33,

34,

35].

5. Concluding Remarks

This paper has reviewed the development of China’s equine industries since 1949, identified major factors contributing to the steady decline in its horse population since 1978, and discussed the challenges and opportunities for the equine industries’ development. Empirical results suggest that the changes in China’s horse population since 1949 have been closely associated with its agricultural and rural development and policies, and key factors for the steady decline in its horse population since 1978 include agricultural mechanization, decrease in the agricultural sector’s share in China’s GDP, improvement in rural transportation (with more tractors, trucks, cars, and motorcycles), urbanization, and decreased land availability for and the lack of economic returns from horses. Such factors may continue to reduce China’s horse population in the coming decade.

A comparative analysis of the development of the equine industries in the United States and China suggests that the economic growth and increase in income in the United States contributed to the rapid growth of the country’s equine sectors since the mid-1960s, but China’s steady economic growth since the late 1970s has contributed to a significant and steady decline in its horse population. However, the rapid development in the tourism, recreation, and sport sectors may provide opportunities for China’s equine industries. As China increases its exchanges with the rest of the world through economic, cultural, and sports activities, many equestrian activities developed in North America and Europe, such as horse-assisted therapy in education and health care, will very likely be introduced in China, with rapidly increasing income and living standards. The growth of China’s equine industries is likely to be more concentrated in Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and the western Sichuan province, all of which have relatively low population density and high proportion of minority ethnic population with the tradition of horses in their cultural, religious, and economic activities. At the same time, equine events and activities are expected to continue to grow at significant rates in and around large Chinese cities.