Carbon Footprint Evaluation of the Business Event Sector in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Background

1.2. Existing Studies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Boundaries

- (1)

- M: The number of participants is 10 or more, use of external facilities (hotels, MICE facilities, etc.), held for more than four hours, and including overseas participants;

- (2)

- I: Ten or more participants, use of external facilities (hotels, MICE facilities, factories, tourist facilities, etc.), held for more than four hours, and participants arrive from overseas for events in Japan;

- (3)

- C-ICCA: A standard international conference per the International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA), an international conference that rotates through more than three countries, the number of participants is 50 or more, and held regularly;

- (4)

- C-JNTO: A standard international conference per the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO). International organizations (including branch offices in each country), or national organizations and domestic organizations (not including private companies) with more than 50 participants is 50, participants from more than three countries including Japan, and held for a period of one day or more; and

- (5)

- E: Among domestic exhibition events, the ratio of overseas participants and exhibitors is high, an event certified as an international exhibition.

2.2. CFP Calculation

3. Results

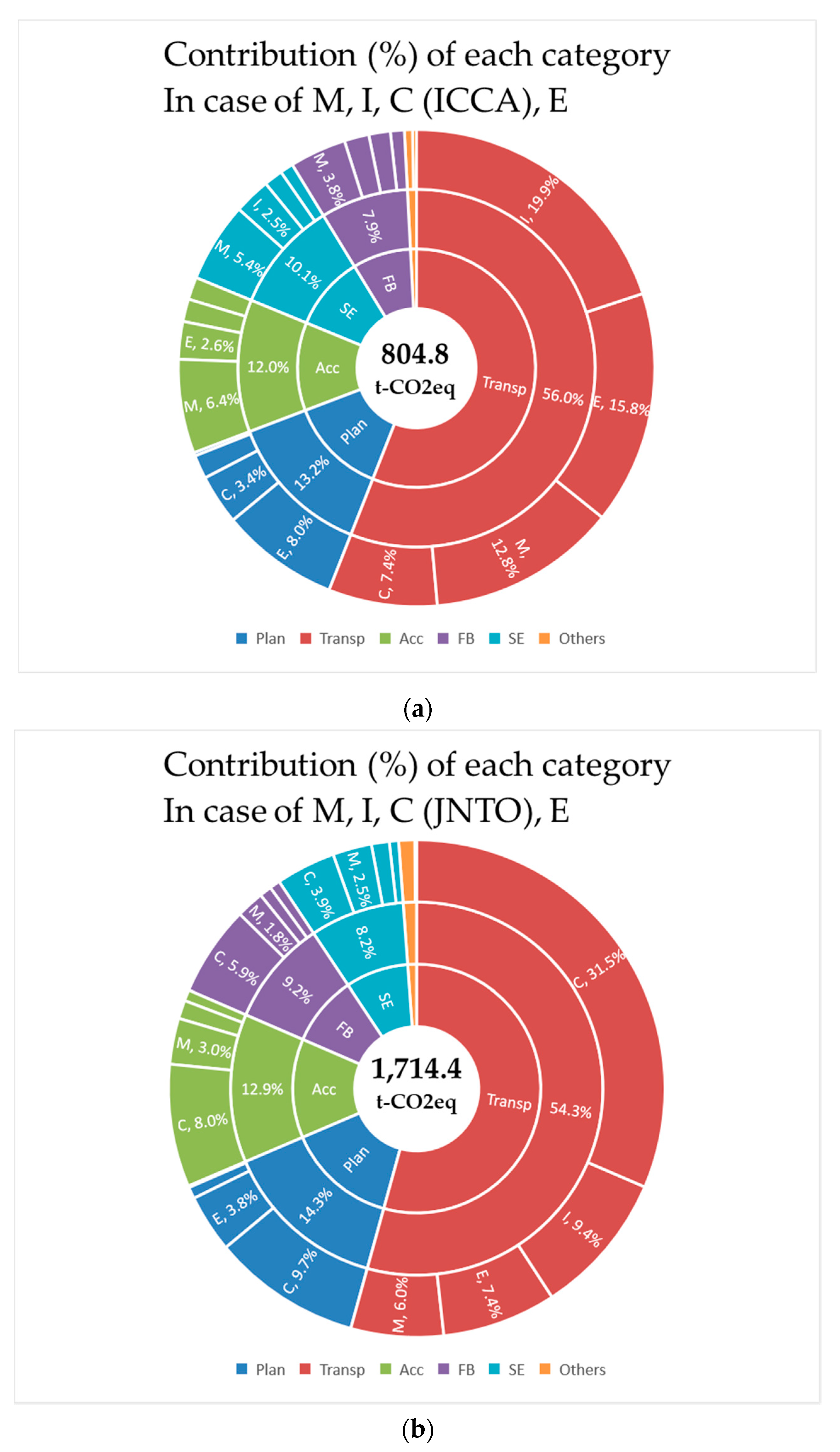

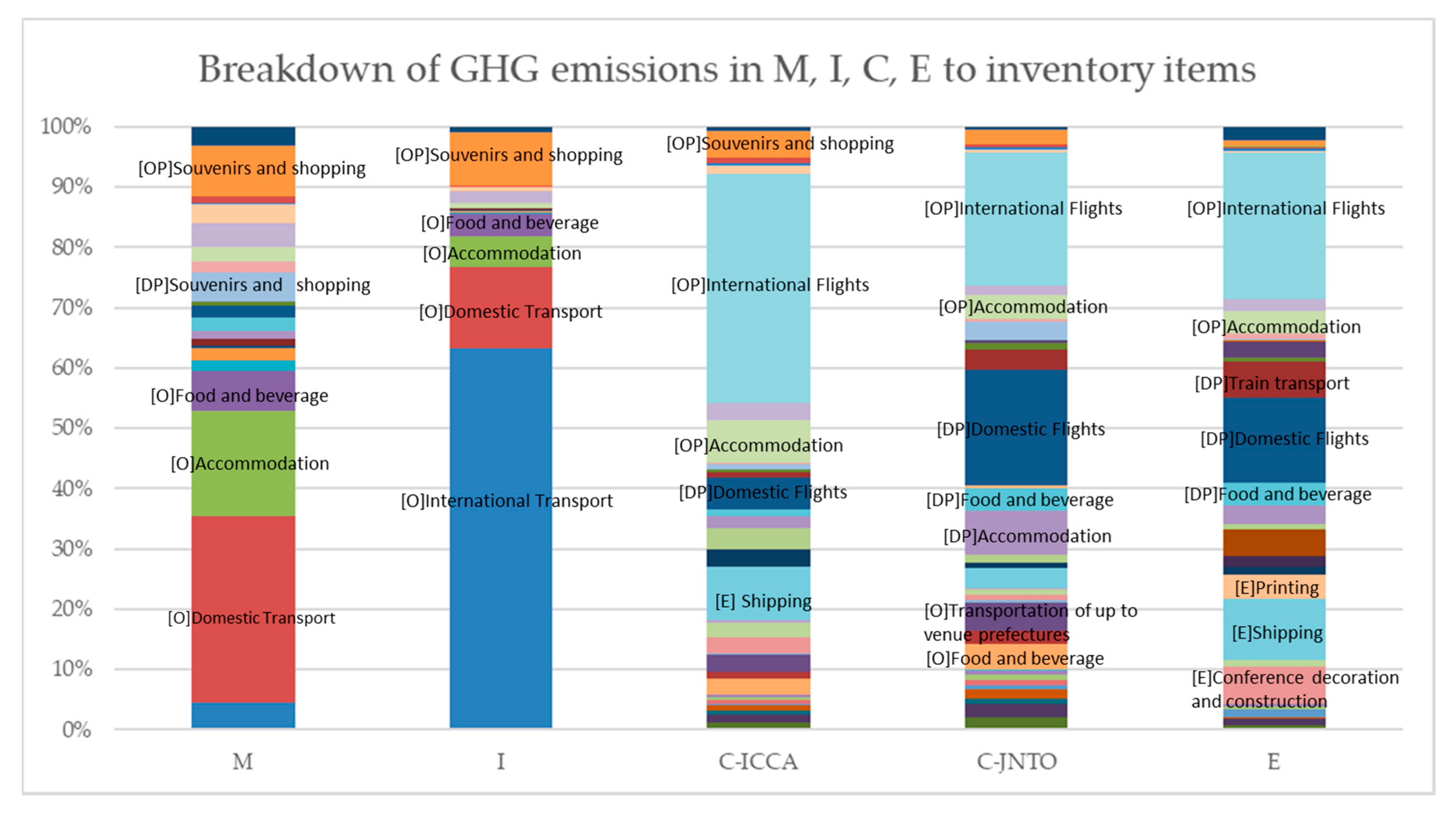

3.1. CFP of MICE

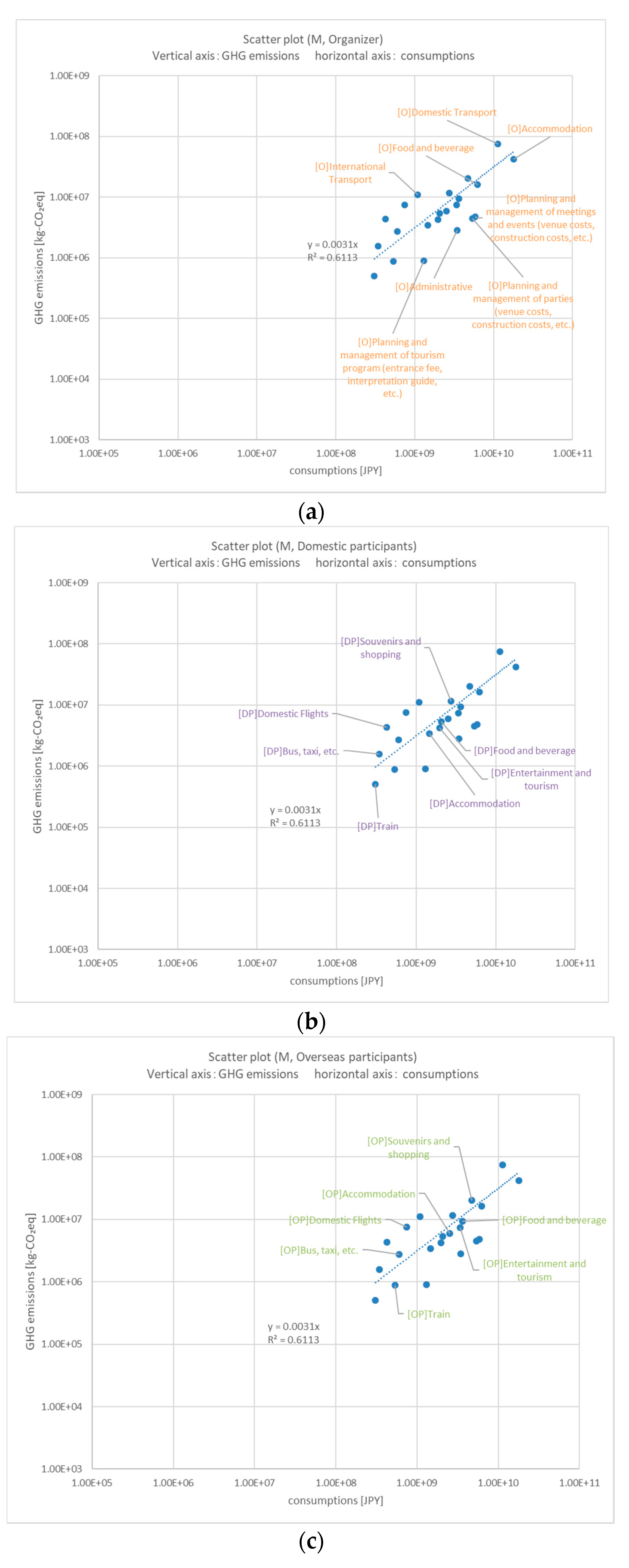

3.2. Meeting

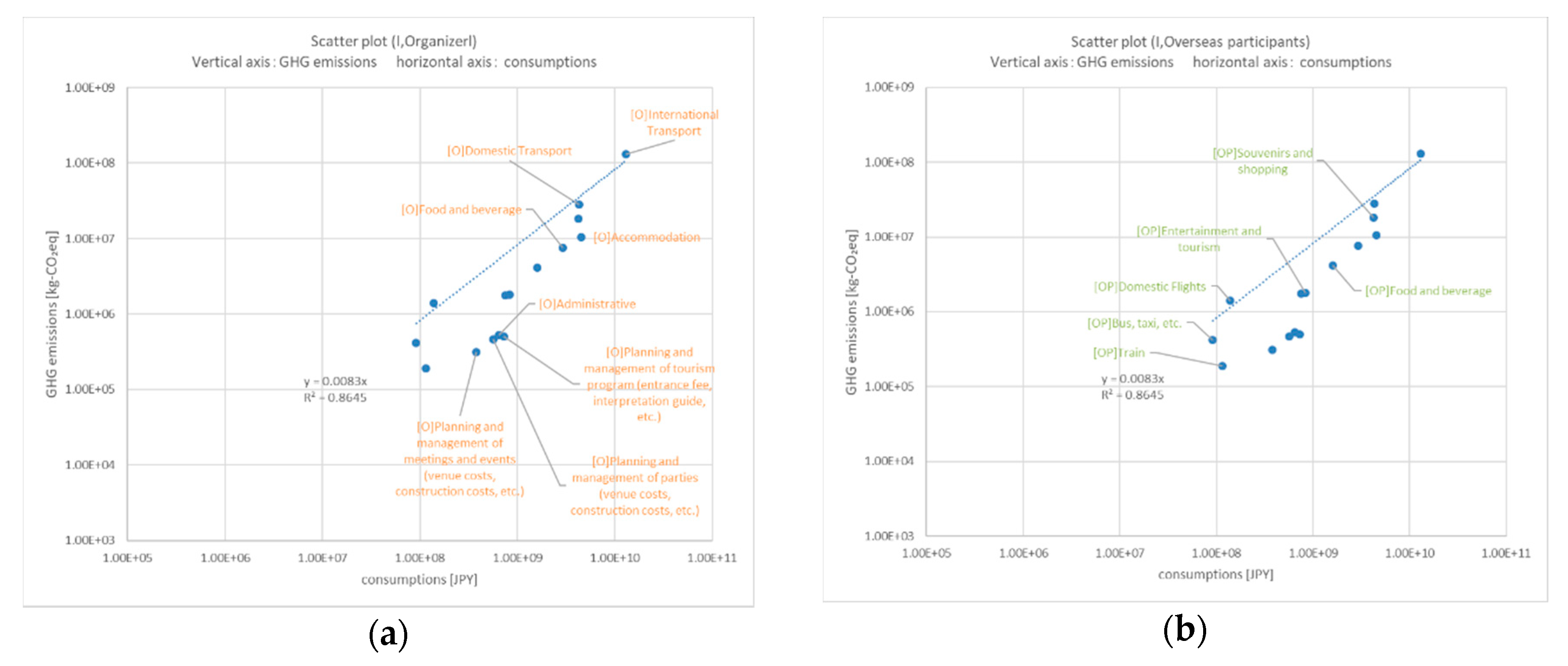

3.3. Incentive Travel

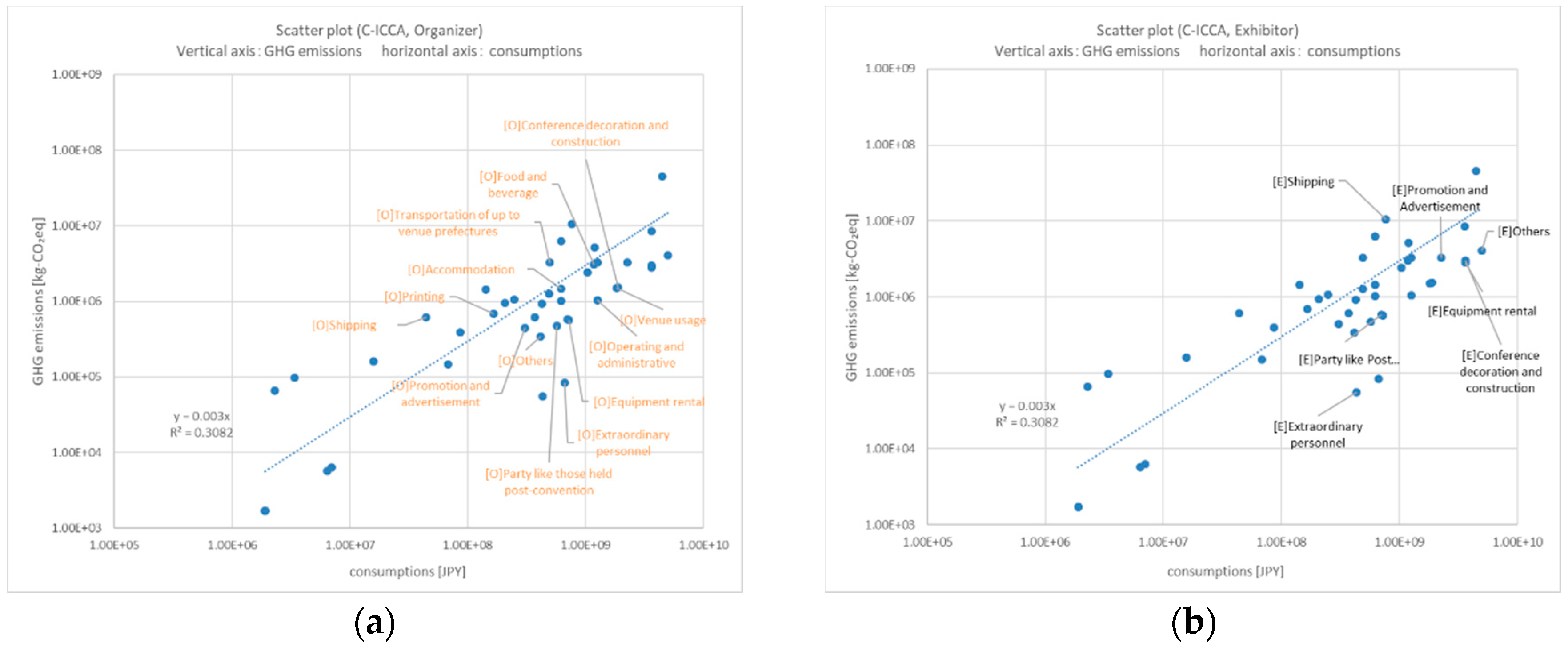

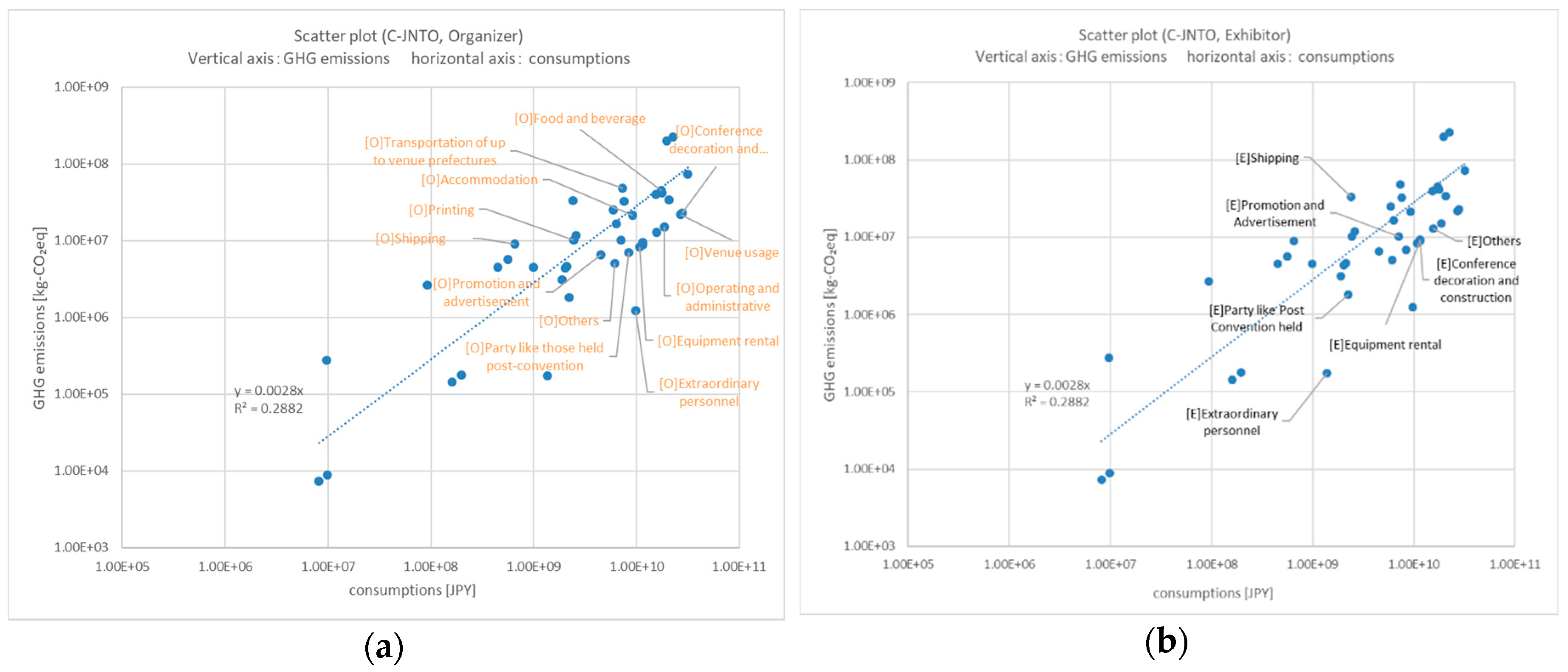

3.4. Convention (ICCA Standard)

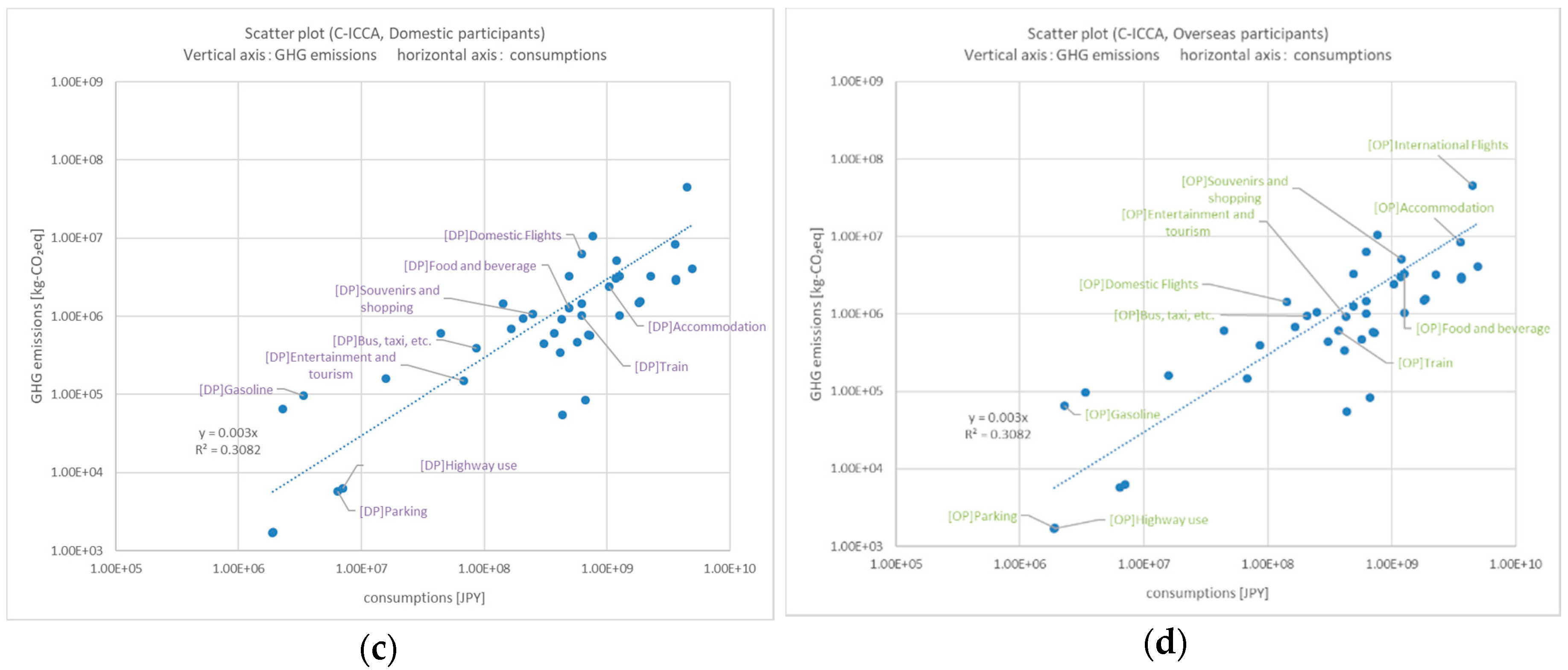

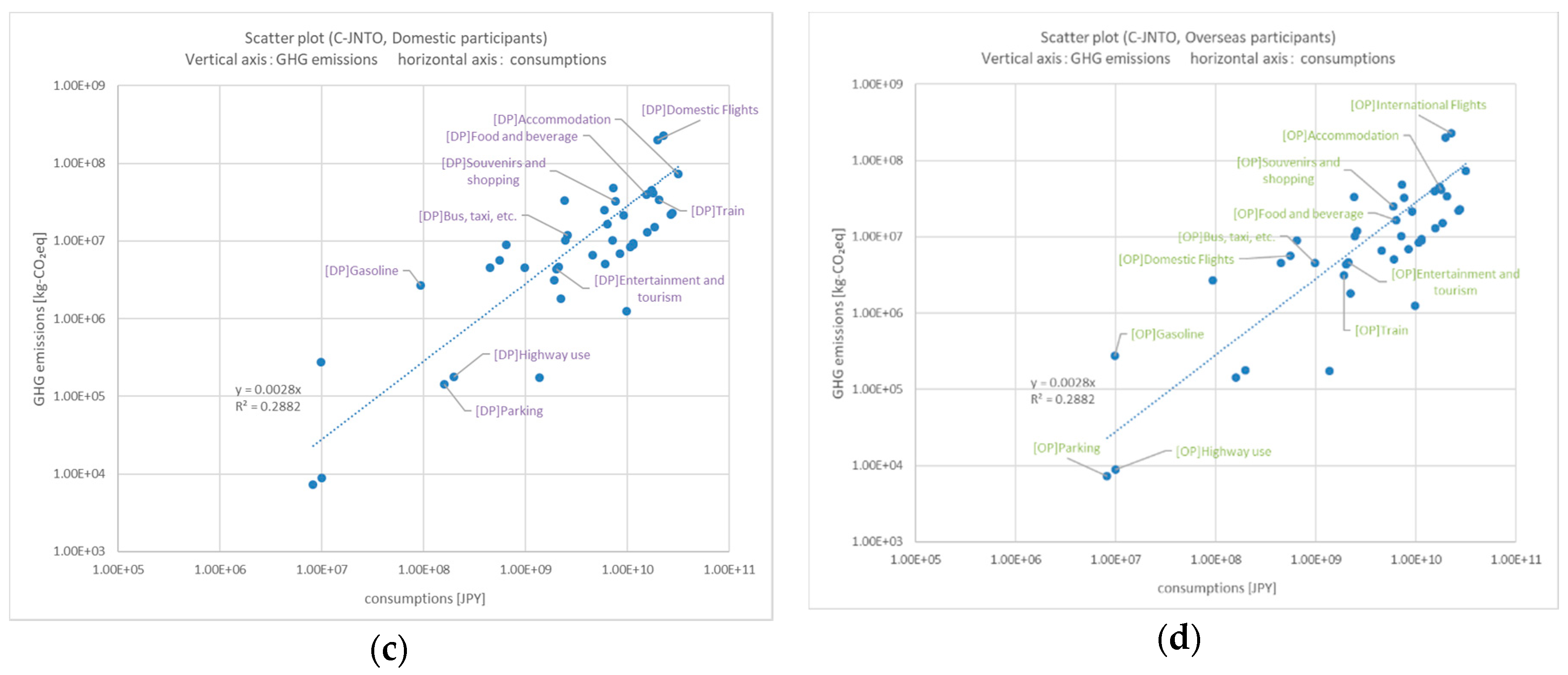

3.5. Conventions (JNTO Standard)

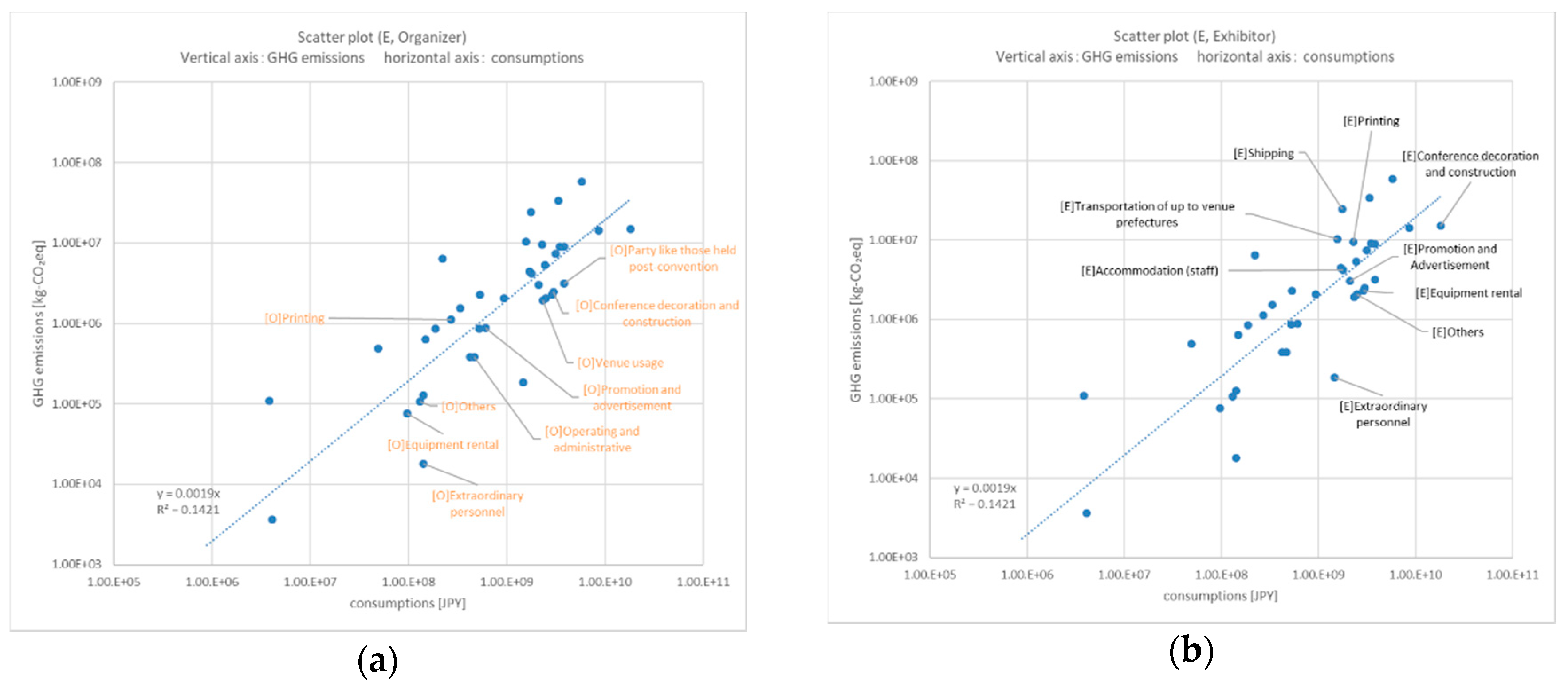

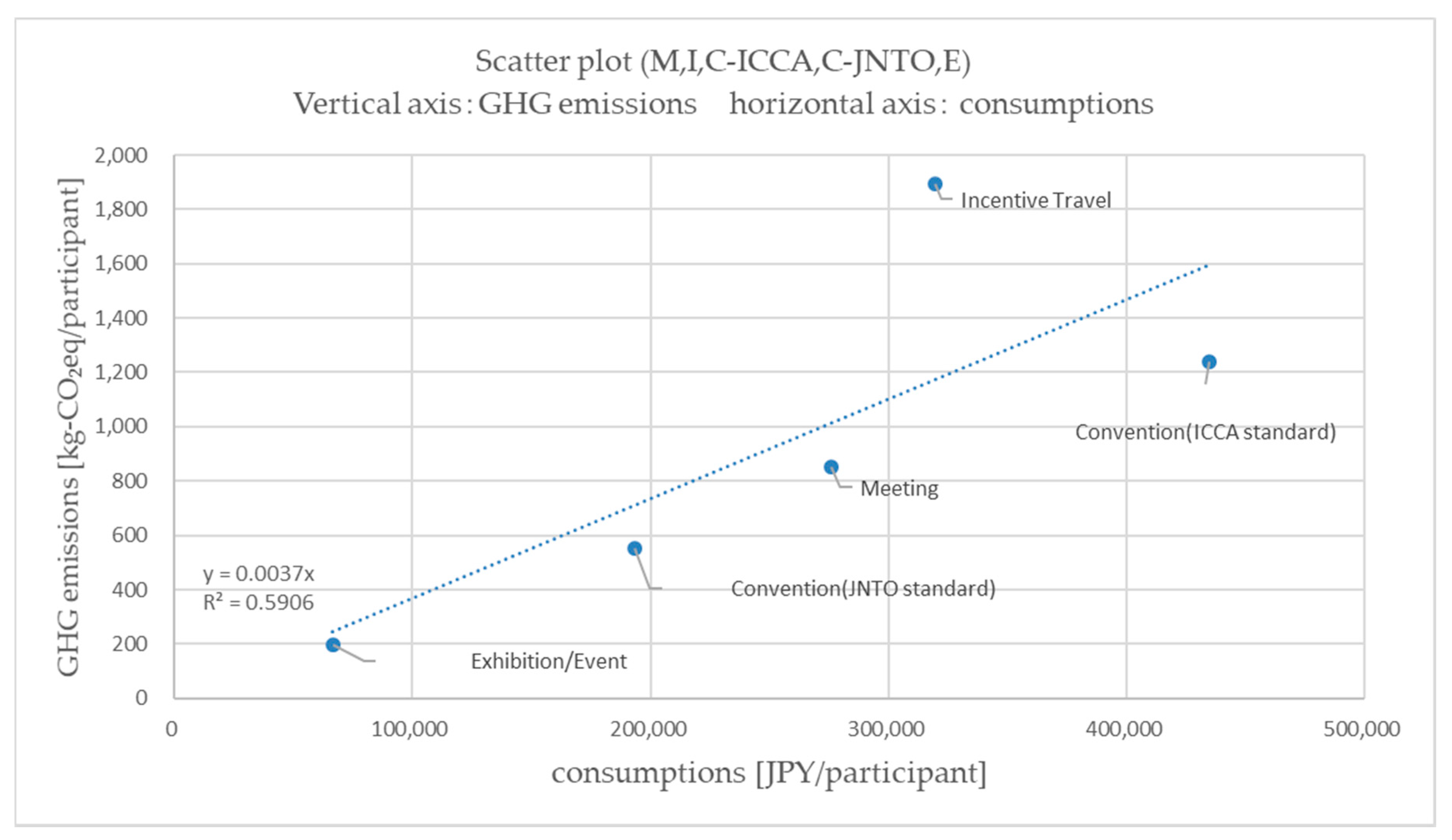

3.6. Exhibition and Event

4. Discussion

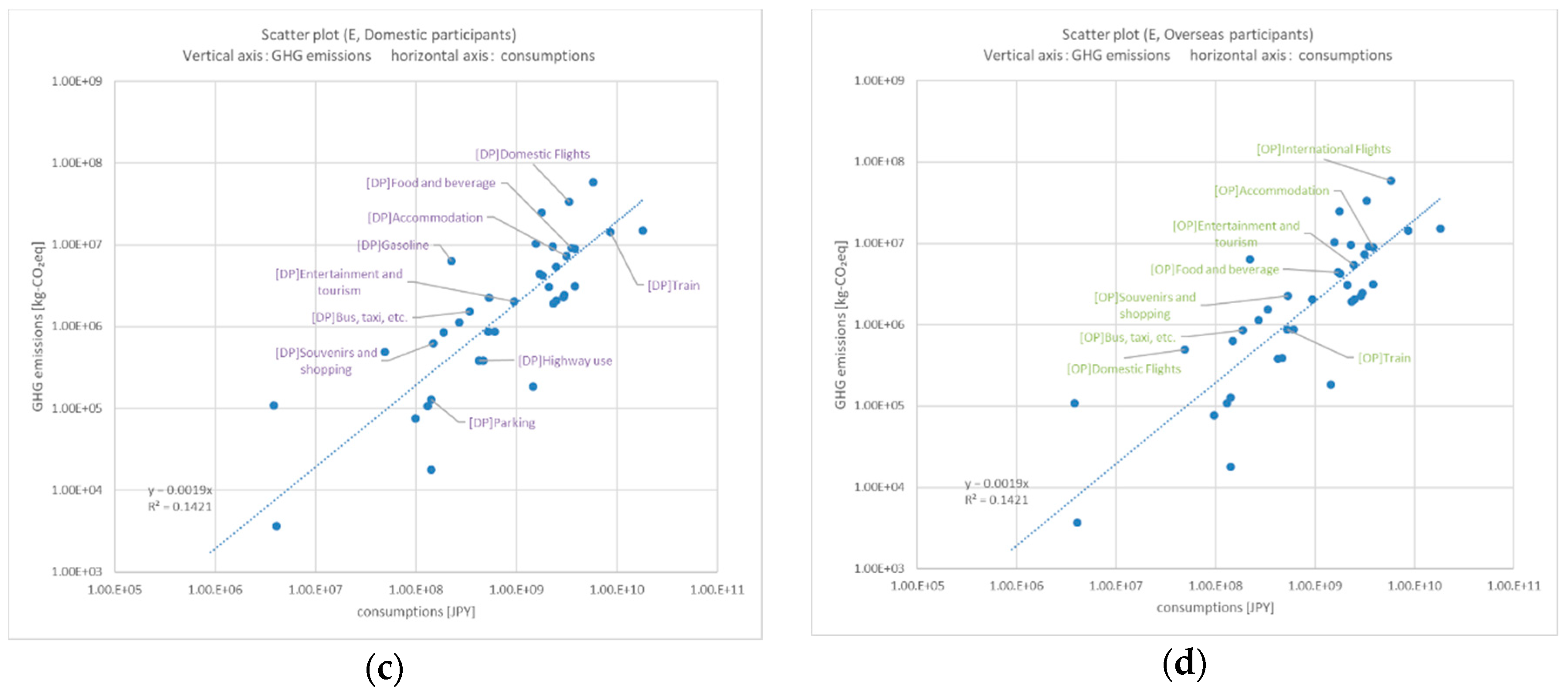

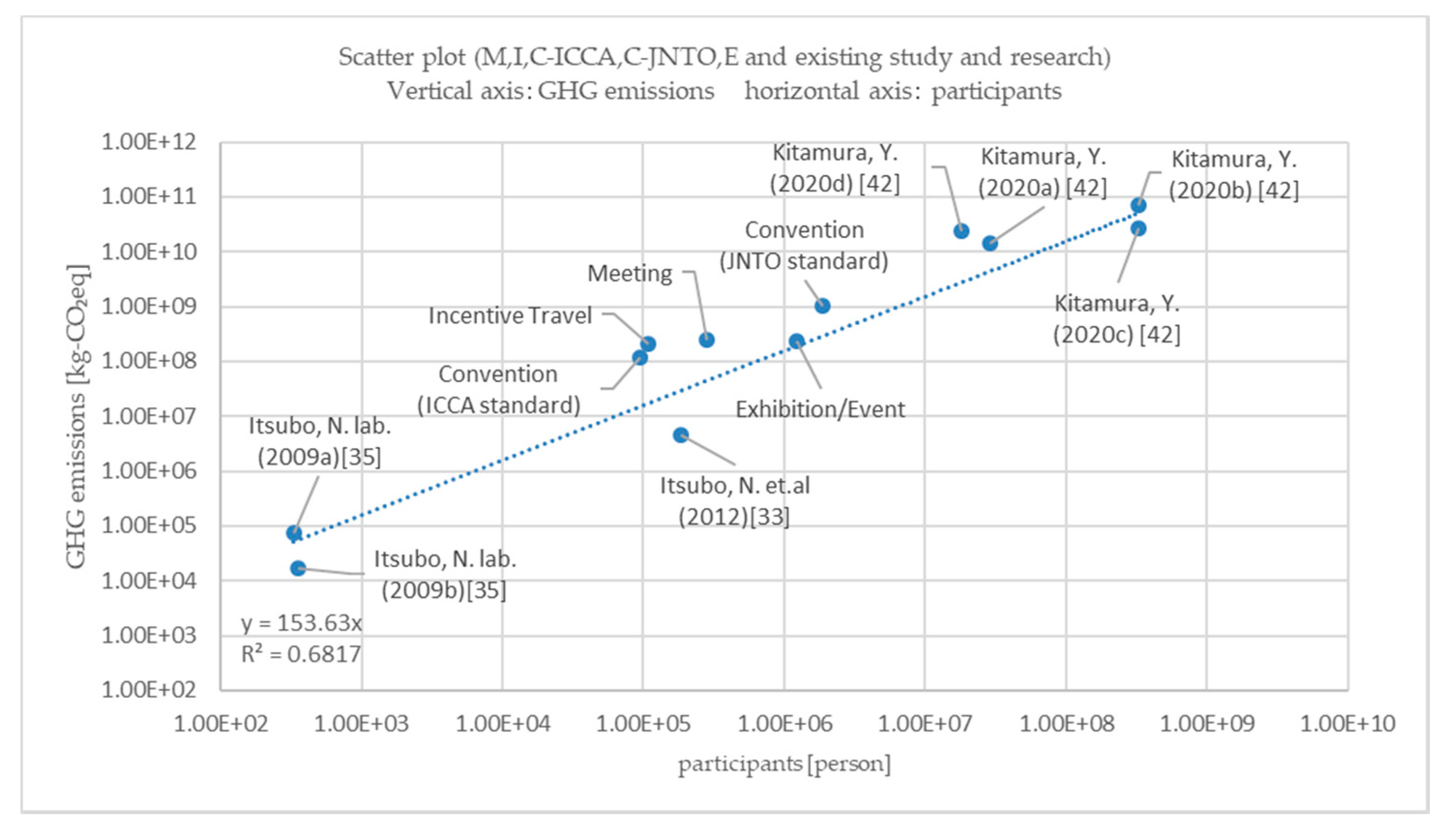

4.1. Comparison with Existing Studies

4.2. Toward the Sustainability of the MICE Sector

4.3. Limitations and Future Investigations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| M | I | C-ICCA | C-JNTO | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M, I, Organizer (O) | |||||

| International transport | 1.09 × 109 | 1.29 × 1010 | - | - | - |

| Domestic transport | 1.13 × 1010 | 4.26 × 109 | - | - | - |

| Accommodation | 1.80 × 1010 | 4.51 × 109 | - | - | - |

| Food and beverage | 6.25 × 109 | 2.94 × 109 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of the party (venue costs, including construction costs, etc.) | 5.43 × 109 | 5.67 × 108 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of such meetings and events (venue costs, including construction costs, etc.) | 5.80 × 109 | 3.78 × 108 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of such tourism programs (entrance fee, including the interpretation guide, etc.) | 1.30 × 109 | 7.29 × 108 | - | - | - |

| Administrative | 3.45 × 109 | 6.48 × 108 | - | - | - |

| C, E, Organizer (O) | |||||

| Venue usage | - | - | 1.82 × 109 | 2.69 × 1010 | 2.33 × 109 |

| Conference decoration and construction | - | - | 1.88 × 109 | 2.77 × 1010 | 2.99 × 109 |

| Equipment rental | - | - | 7.25 × 108 | 1.07 × 1010 | 9.77 × 107 |

| Operating and administrative | - | - | 1.26 × 109 | 1.85 × 1010 | 4.67 × 108 |

| Parties like those held post-convention | - | - | 5.72 × 108 | 8.44 × 109 | 3.82 × 109 |

| Shipping | - | - | 4.41 × 107 | 6.50 × 108 | - |

| Printing | - | - | 1.66 × 108 | 2.45 × 109 | 2.72 × 108 |

| Promotion and advertisement | - | - | 3.08 × 108 | 4.53 × 109 | 6.08 × 108 |

| Extraordinary personnel | - | - | 6.65 × 108 | 9.80 × 109 | 1.41 × 108 |

| Food and beverage | - | - | 1.17 × 109 | 1.73 × 1010 | - |

| Accommodation (staff) | - | - | 6.25 × 108 | 9.21 × 109 | - |

| Transportation of up to venue prefectures | - | - | 4.95 × 108 | 7.29 × 109 | - |

| Others | - | - | 4.14 × 108 | 6.10 × 109 | 1.30 × 108 |

| Exhibitor (E) | |||||

| Conference decoration and construction | - | - | 3.64 × 109 | 1.14 × 1010 | 1.83 × 1010 |

| Equipment rental | - | - | 3.64 × 109 | 1.14 × 1010 | 2.92 × 109 |

| Parties like those held post-convention (venue costs, including construction costs, etc.) | - | - | 7.07 × 108 | 2.22 × 109 | - |

| Shipping | - | - | 7.66 × 108 | 2.41 × 109 | 1.77 × 109 |

| Printing | - | - | - | - | 2.29 × 109 |

| Promotion and advertisement | - | - | 2.26 × 109 | 7.11 × 109 | 2.12 × 109 |

| Extraordinary personnel | - | - | 4.36 × 108 | 1.37 × 109 | 1.46 × 109 |

| Accommodation (staff) | - | - | - | - | 1.81 × 109 |

| Transportation of up to venue prefectures | - | - | - | - | 1.56 × 109 |

| Others | - | - | 4.97 × 109 | 1.56 × 1010 | 2.50 × 109 |

| Domestic participants (DP) | |||||

| Accommodation | 1.46 × 109 | - | 1.04 × 109 | 3.17 × 1010 | 3.15 × 109 |

| Food and beverage | 2.09 × 109 | - | 4.90 × 108 | 1.54 × 1010 | 3.51 × 109 |

| International flights | - | - | 1.58 × 107 | 4.49 × 108 | - |

| Domestic flights | 4.28 × 108 | - | 6.24 × 108 | 1.97 × 1010 | 3.34 × 109 |

| Train | 3.07 × 108 | - | 6.19 × 108 | 2.05 × 1010 | 8.68 × 109 |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 3.44 × 108 | - | 8.62 × 107 | 2.60 × 109 | 3.38 × 108 |

| Gasoline | - | - | 3.40 × 106 | 9.30 × 107 | 2.24 × 108 |

| Parking | - | - | 6.41 × 106 | 1.60 × 108 | 1.41 × 108 |

| Highway use | - | - | 7.02 × 106 | 1.97 × 108 | 4.24 × 108 |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 2.74 × 109 | - | 2.49 × 108 | 7.61 × 109 | 1.48 × 108 |

| Entertainment and tourism | 1.96 × 109 | - | 6.83 × 107 | 2.01 × 109 | 9.45 × 108 |

| Overseas participants (OP) | |||||

| Accommodation | 2.54 × 109 | 7.53 × 108 | 3.60 × 109 | 1.78 × 1010 | 3.85 × 109 |

| Food and beverages | 3.62 × 109 | 1.60 × 109 | 1.27 × 109 | 6.34 × 109 | 1.71 × 109 |

| International flights | - | - | 4.47 × 109 | 2.24 × 1010 | 5.79 × 109 |

| Domestic flights | 7.44 × 108 | 1.39 × 108 | 1.43 × 108 | 5.58 × 108 | 4.89 × 107 |

| Train | 5.34 × 108 | 1.16 × 108 | 3.71 × 108 | 1.90 × 109 | 5.27 × 108 |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 5.99 × 108 | 9.17 × 107 | 2.07 × 108 | 9.87 × 108 | 1.87 × 108 |

| Gasoline | - | - | 2.29 × 106 | 9.73 × 106 | 3.82 × 106 |

| Parking | - | - | 1.91 × 106 | 8.16 × 106 | 4.07 × 106 |

| Highway use | - | - | 1.90 × 106 | 9.89 × 106 | 8.91 × 105 |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 4.76 × 109 | 4.26 × 109 | 1.20 × 109 | 5.92 × 109 | 5.32 × 108 |

| Entertainment and tourism | 3.40 × 109 | 8.30 × 108 | 4.26 × 108 | 2.11 × 109 | 2.47 × 109 |

| Total | 7.82 × 1010 | 3.48 × 1010 | 4.15 × 1010 | 3.60 × 1011 | 8.16 × 1010 |

| Product and Service | Coefficient (kg CO2 eq/JPY) | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Code | Code Name | ||

| Travel agencies, tour operators, and tourist guide services | |||

| Travel agencies, tour operators, and tourist guide services | 6.88 × 104 | 5789090 | Travel and other transportation incidental services |

| Passenger transport | |||

| Airplane (domestic, local) | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Airplane (international flight) | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Bullet train | 1.64 × 103 | 5711010 | Railway transport |

| Railways (excluding bullet train) | 1.64 × 103 | 5711010 | Railway transport |

| Bus | 4.16 × 103 | 5721010 | bus |

| Taxi | 4.93 × 103 | 5721020 | taxi |

| Ships (inner service, local) | 1.23 × 102 | 5742010 | Marine and inland water |

| Ships (outbound) | 2.57 × 103 | 5741010 | Ocean |

| Car rental fee | 7.86 × 104 | 6612010 | Car rental |

| Gasoline cost | 7.55 × 103 | 2111010 | Petrol |

| 2.10 × 102 | - | Petrol(direct) | |

| Parking lots, toll road charges (except for highway charge), highway charges | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road |

| Highway charges | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road |

| Accommodation services | |||

| Accommodation services | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Vacation home ownership (imputed) | 2.37 × 104 | 5531010 | Vacation home ownership (imputed) |

| Food and beverage | |||

| Food and beverage serving services | 2.59 × 103 | 6721010 | Food and beverage |

| Souvenirs and shopping | |||

| Agricultural products | 2.10 × 103 | 116090 | Other non-food cropping crops |

| Agricultural processed products | 3.12 × 103 | 1116020 | Agro-preserved food products (except bottles and cans) |

| Marine products | 6.07 × 103 | 172001 | Inland fishery and aquaculture |

| Fisheries processed products | 5.04 × 103 | 1113090 | Other seafood |

| Confectionery | 3.66 × 103 | 1115030 | Confectionery |

| Other food items | 5.54 × 103 | 1119090 | food items |

| Fiber products | 6.58 × 103 | 1519090 | textile products |

| Shoes, bags | 3.05 × 103 | 2229010 | footwear |

| Ceramics and glass products | 2.91 × 103 | 2312020 | Bags, bags and other leather products |

| Publication | 3.43 × 103 | 5951030 | Publication |

| Wood products and paper products | 5.62 × 103 | 1649090 | Other pulp, paper and paper products |

| Medical supplies and cosmetics | 3.69 × 103 | 2081020 | Cosmetics |

| Film | 6.18 × 103 | 2083010 | Photosensitive material |

| Electrical equipment and related products | 3.61 × 103 | 3321020 | Consumer electrical appliances (except air conditioners) |

| Camera, glasses, watch | 3.26 × 103 | 3919090 | Other manufactured industrial products |

| Sports equipment, CD (Compact disc), stationery | 3.26 × 103 | 3919090 | Other manufactured industrial products |

| Other manufactured products | 3.26 × 103 | 3919090 | Other manufactured industrial products |

| Activity (cultural services, recreation, other entertainment services, and other services) | |||

| A day spa, warm-bathing facility, beauty salon | 3.81 × 103 | 6731040 | Bathing |

| Museums, museums, zoos and gardens, aquariums | 2.30 × 103 | 6312010 | Social education (public) |

| Watching sports, art appreciation | 1.01 × 103 | 6741020 | Office space (except movie theaters) and entertainment companies |

| Amusement parks and expositions | 1.01 × 103 | 6741020 | Office space (except movie theaters) and entertainment companies |

| Sports facilities | 1.34 × 103 | 6741040 | Sports facility offer work, park, amusement park |

| Ski lift fee | 1.64 × 103 | 5711010 | Railway |

| Camp site | 1.34 × 103 | 6741040 | Sports facility offer work, park, amusement park |

| Exhibition and convention participation fee | 6.27 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Tourist farm | 4.56 × 103 | 131020 | Agricultural services (except for veterinary services) |

| Fishing boat | 1.45 × 103 | 6741090 | Other entertainment |

| Guide fee | 8.22 × 104 | 6799090 | Other personal services |

| Rental charge | 7.80 × 104 | 6611010 | Goods rental business (excluding rental cars) |

| Massage | 1.06 × 103 | 6411050 | Medical (other medical services) |

| Photo shoot fee | 1.10 × 103 | 6799010 | Photography |

| Mail and communication charges | 1.51 × 103 | 5791010 | Postal and letter mail |

| Home delivery | 1.38 × 102 | 5722010 | delivery |

| Travel insurance, credit card admission fee | 6.78 × 104 | 5312010 | Life insurance |

| Passport application fee | 8.16 × 104 | 6112010 | Government (local) |

| Visa application fee | 8.16 × 104 | 6112010 | Government (local) |

| Hairdresser, barber | 9.50 × 104 | 6731030 | Beauty industry |

| Develop and print photos | 8.22 × 104 | 6799090 | Other personal services |

| Laundry service | 1.74 × 103 | 6731010 | laundry service |

| Other | 8.22 × 104 | 6799090 | Other personal services |

| Product and Service Spending | Coefficient (kg CO2 eq/JPY) | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Code | Code Name | ||

| M, I, Organizer (O) | |||

| International transport | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Domestic transport | 6.60 × 103 | - | Average of transport |

| Accommodation | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Food and beverage | 2.59 × 103 | 6721010 | Food and beverage |

| Planning and management of parties (venue costs, including construction costs, etc.) | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Planning and management of meetings and events (venue costs, including construction costs, etc.) | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Planning and management of tourism program (entrance fee, including the interpretation guide, etc.) | 6.88 × 104 | 5789090 | Travel and other transportation incidental services |

| Administrative | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| C, E, Organizer (O) | |||

| Venue usage | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Conference decoration and construction | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Equipment rental | 7.80 × 104 | 6611010 | Goods rental business (excluding rental cars) |

| Operating and administrative | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Parties like those held post-convention | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Shipping | 1.38 × 102 | 5722010 | delivery |

| Printing | 4.14 × 103 | 1911010 | Printing |

| Promotion and advertisement | 1.44 × 103 | 6621010 | Promotion and Advertisement |

| Extraordinary personnel | 1.26 × 104 | 6699030 | Worker dispatching service |

| Food and beverage | 2.59 × 103 | 6721010 | Food and beverage |

| Accommodation (staff) | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Transportation of up to venue prefectures | 6.60 × 103 | - | Average of transport |

| Others | 8.22 × 104 | 6799090 | Other personal services |

| Exhibitor (E) | |||

| Conference decoration and construction | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Equipment rental | 7.80 × 104 | 6611010 | Goods rental business (excluding rental cars) |

| Parties like those held post-convention (venue costs, construction costs, etc.) | 8.22 × 104 | 6699090 | Other business services |

| Shipping | 1.38 × 102 | 5722010 | delivery |

| Printing | 4.14 × 103 | 1911010 | Printing |

| Promotion and advertisement | 1.44 × 103 | 6621010 | Promotion and Advertisement |

| Extraordinary personnel | 1.26 × 104 | 6699030 | Worker dispatching service |

| Accommodation (staff) | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Transportation to venue | 6.60 × 103 | - | Average of transport |

| Others | 8.22 × 104 | 6799090 | Other personal services |

| Domestic participants (DP) | |||

| Accommodation | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Food and beverage | 2.59 × 103 | 6721010 | Food and beverage |

| International flights | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Domestic flights | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Trains | 1.64 × 103 | 5711010 | Railway transport |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 4.55 × 103 | - | Average of Bus and Taxi |

| Gasoline | 2.86 × 102 | 2111010 | Petrol and Petrol(direct) |

| Parking | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road transport facilities |

| Highway use | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road transport facilities |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 4.26 × 103 | - | Average of souvenir |

| Entertainment and tourism | 2.17 × 103 | - | Average of Activity |

| Overseas participants (OP) | |||

| Accommodation | 2.33 × 103 | 6711010 | Accommodation |

| Food and beverages | 2.59 × 103 | 6721010 | Food and beverage |

| International flights | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Domestic flights | 1.01 × 102 | 5751010 | Air transport |

| Train | 1.64 × 103 | 5711010 | Railway transport |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 4.55 × 103 | - | Average of Bus and Taxi |

| Gasoline | 2.86 × 102 | 2111010 | Petrol and Petrol(direct) |

| Parking | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road transport facilities |

| Highway use | 8.98 × 104 | 5789010 | Road transport facilities |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 4.26 × 103 | - | Average of souvenir |

| Entertainment and tourism | 2.17 × 103 | - | Average of Activity |

| M | I | C-ICCA | C-JNTO | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M, I, Organizer (O) | |||||

| International transport | 1.10 × 107 | 1.30 × 108 | - | - | - |

| Domestic transport | 7.48 × 107 | 2.81 × 107 | - | - | - |

| Accommodation | 4.19 × 107 | 1.05 × 107 | - | - | - |

| Food and beverage | 1.62 × 107 | 7.61 × 106 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of parties (venue costs, construction costs, etc.) | 4.47 × 106 | 4.66 × 105 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of meetings and events (venue costs, construction costs, etc.) | 4.77 × 106 | 3.11 × 105 | - | - | - |

| Planning and management of tourism program (entrance fee, interpretation guide, etc.) | 8.94 × 105 | 5.01 × 105 | - | - | - |

| Administrative | 2.84 × 106 | 5.33 × 105 | - | - | - |

| C, E, Organizer (O) | |||||

| Venue usage | - | - | 1.50 × 106 | 2.21 × 107 | 1.92 × 106 |

| Conference decoration and construction | - | - | 1.55 × 106 | 2.28 × 107 | 2.46 × 106 |

| Equipment rental | - | - | 5.66 × 105 | 8.34 × 106 | 7.62 × 104 |

| Operating and administrative | - | - | 1.03 × 106 | 1.52 × 107 | 3.84 × 105 |

| Parties like those held post-convention | - | - | 4.71 × 105 | 6.94 × 106 | 3.14 × 106 |

| Shipping | - | - | 6.11 × 105 | 9.00 × 106 | - |

| Printing | - | - | 6.87 × 105 | 1.01 × 107 | 1.12 × 106 |

| Promotion and advertisement | - | - | 4.42 × 105 | 6.52 × 106 | 8.74 × 105 |

| Extraordinary personnel | - | - | 8.39 × 104 | 1.24 × 106 | 1.78 × 104 |

| Food and beverage | - | - | 3.04 × 106 | 4.47 × 107 | - |

| Accommodation (staff) | - | - | 1.46 × 106 | 2.15 × 107 | - |

| Transportation of up to venue prefectures | - | - | 3.26 × 106 | 4.81 × 107 | - |

| Others | - | - | 3.40 × 105 | 5.01 × 106 | 1.07 × 105 |

| Exhibitor (E) | |||||

| Conference decoration and construction | - | - | 2.99 × 106 | 9.41 × 106 | 1.50 × 107 |

| Equipment rental | - | - | 2.84 × 106 | 8.92 × 106 | 2.28 × 106 |

| Parties like those held post-convention (venue costs, construction costs, etc.) | - | - | 5.81 × 105 | 1.83 × 106 | - |

| Shipping | - | - | 1.06 × 107 | 3.33 × 107 | 2.45 × 107 |

| Printing | - | - | - | - | 9.48 × 106 |

| Promotion and advertisement | - | - | 3.25 × 106 | 1.02 × 107 | 3.05 × 106 |

| Extraordinary personnel | - | - | 5.50 × 104 | 1.73 × 105 | 1.84 × 105 |

| Accommodation (staff) | - | - | - | - | 4.21 × 106 |

| Transportation of up to venue prefectures | - | - | - | - | 1.03 × 107 |

| Others | - | - | 4.09 × 106 | 1.28 × 107 | 2.06 × 106 |

| Domestic participants (DP) | |||||

| Accommodation | 3.41 × 106 | - | 2.42 × 106 | 7.38 × 107 | 7.35 × 106 |

| Food and beverage | 5.39 × 106 | - | 1.27 × 106 | 3.98 × 107 | 9.06 × 106 |

| International flights | - | - | 1.59 × 105 | 4.53 × 106 | - |

| Domestic flights | 4.32 × 106 | - | 6.29 × 106 | 1.98 × 108 | 3.37 × 107 |

| Train | 5.05 × 105 | - | 1.02 × 106 | 3.38 × 107 | 1.43 × 10 |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 1.57 × 106 | - | 3.92 × 105 | 1.18 × 107 | 1.54 × 106 |

| Gasoline | - | - | 9.72 × 104 | 2.66 × 106 | 6.39 × 106 |

| Parking | - | - | 5.75 × 103 | 1.44 × 105 | 1.27 × 105 |

| Highway use | - | - | 6.31 × 103 | 1.77 × 105 | 3.81 × 105 |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 1.17 × 107 | - | 1.06 × 106 | 3.24 × 107 | 6.32 × 105 |

| Entertainment and tourism | 4.24 × 106 | - | 1.48 × 105 | 4.37 × 106 | 2.05 × 106 |

| Overseas participants (OP) | |||||

| Accommodation | 5.92 × 106 | 1.76 × 106 | 8.41 × 106 | 4.16 × 107 | 8.97 × 106 |

| Food and beverages | 9.37 × 106 | 4.14 × 106 | 3.27 × 106 | 1.64 × 107 | 4.42 × 106 |

| International flights | - | - | 4.51 × 107 | 2.26 × 108 | 5.83 × 107 |

| Domestic flights | 7.50 × 106 | 1.40 × 106 | 1.44 × 106 | 5.63 × 106 | 4.93 × 105 |

| Train | 8.78 × 105 | 1.90 × 105 | 6.10 × 105 | 3.13 × 106 | 8.67 × 105 |

| Bus, taxi, etc. | 2.72 × 106 | 4.17 × 105 | 9.42 × 105 | 4.49 × 106 | 8.53 × 105 |

| Gasoline | - | - | 6.55 × 104 | 2.78 × 105 | 1.09 × 105 |

| Parking | - | - | 1.71 × 103 | 7.33 × 103 | 3.66 × 103 |

| Highway use | - | - | 1.70 × 103 | 8.88 × 103 | 8.00 × 102 |

| Souvenirs and shopping | 2.03 × 107 | 1.81 × 107 | 5.11 × 106 | 2.52 × 107 | 2.27 × 106 |

| Entertainment and tourism | 7.37 × 106 | 1.80 × 106 | 9.25 × 105 | 4.59 × 106 | 5.37 × 106 |

| Total | 2.42 × 108 | 2.06 × 108 | 1.18 × 108 | 1.03 × 109 | 2.38 × 108 |

References

- 2017 International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development. Available online: http://www.tourism4development2017.org/about/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Sustainable Tourism for Development Guidebook–Enhancing Capacities for Sustainable Tourism for Development in Developing Countries; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). Significance of MICE. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/shisaku/kokusai/mice.html#igi (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). A Vision for Tourism That Will Support Japan Tomorrow. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/topics01_000205.html (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Events Industry Council (EIC). The Economic Significance of Meetings to the U.S. Economy. 2012. Available online: https://insights.eventscouncil.org/Portals/0/2016.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Li, S.; Bowdin, G.; Heslington, E.; Jones, S.; Mulligan, J.; Tara-Lunga, M.; Tauxe, C.; Thomas, R.; Wu, P.; Blake, A.; et al. The Economic Impact of the UK Meeting & Event Industry. 2013. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277308949 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Kahn, K.; Andersen, C.; Dissing, S. The Economic Contribution of Meeting Activity in Denmark; Visit Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Business Events Council of Australia. The Value of Business Events to Australia. 2015. Available online: https://www.businesseventscouncil.org.au/files/View_Report.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA). Study on the Economic MICE in Singapore. 2016. Available online: http://www.iccaworld.org/dcps/doc.cfm?docid=1948 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Frost & Sullivan. The Study on the Economic Impact of MICE Industry in Thailand; Thailand Convention & Exhibition Bureau: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Standard. Event Sustainability Management Systems—Requirements With Guidance for Use, 1st ed.; ISO 20121: 2012(E); ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Green Meeting Guide 2009. Available online: https://www.greeningtheblue.org/sites/default/files/GreenMeetingGuide.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Sustainable Events Guide—Give Your Large Event a Small Footprint. 2012. Available online: https://www.greeningtheblue.org/sites/default/files/Sustainable%20Events%20Guide%20May%2030%202012%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Singapore Tourism Board. Sustainability Guidelines for the Singapore Mice Industry. 2013. Available online: https://www.visitsingapore.com/content/dam/MICE/Global/useful-downloads/sustainability-guidelines-for-mice.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Thailand Convention and Exhibition Bureau (TCEB). Thailand Sustainable Events Guide. 2015. Available online: http://www.micecapabilities.com/mice/uploads/attachments/Thailand_Sustainable_Events_Guide_(TH).pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Ministry of Economic Affairs, Bureau of Foreign Trade. 2016 Green MICE Guidelines. Available online: https://venweb.meettaiwan.com/static/download/2016-Green-MICE-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan. Recommendations for Environmentally Friendly Meetings. 2008. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/policy/kaigi_hairyo/tebiki.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Tokyo Convention and Visitors Bureau (TCVB). Sustainability Guidelines for Business Events in Tokyo. 2019. Available online: https://businesseventstokyo.org/tokyo-mice-sustainability-guidelines/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate. Change (UNFCCC). The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations Environment Programme (2019). Emissions Gap Report 2019. UNEP, Nairobi. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2019 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan. Submission of Japan’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/press/files/jp/113675.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- The Long-Term Strategy Under the Paris Agreement. The Government of Japan, Tokyo. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/press/111913.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). SDG Compass The Guide for Business Action on the SDGs. Available online: https://sdgcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/019104_SDG_Compass_Guide_2015.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). TOURISM FOR SDGs. Available online: http://tourism4sdgs.org/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Mair, J.; Jago, L. The development of a conceptual model of greening in the business events tourism sector. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Nolan, E. Green Events and Green Tourism an International Guide to Good Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games. London 2012 Carbon Footprint Study—Methodology and Reference Footprint. 2010. Available online: https://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/255/_arquivos/carbon_footprint_study_relat_255.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC). SETAC Europe 30th Annual Meeting Sustainability Initiatives. Available online: https://dublin.setac.org/general-info/sustainability-2/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Itsubo, N.; Horiguchi, K.; Tang, L.; Hiruma, M.; Sekiguchi, N. Environmental analysis for international marathon event based on the life cycle perspectives. J. Life Cycle Assess. Jpn. 2009, 5, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap Bank Fes’08. Eco-Report. Available online: http://fes.apbank.jp/08/ecorepo/ (accessed on 13 May 2020). (In Japanese).

- Tokyo City University. Carbon Offset Student Project at the School Festival. Available online: https://www.comm.tcu.ac.jp/carbonoffset/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Horiguchi, K.; Itsubo, N. Development of emission intensity database for event LCA. In Proceedings of the 4th Meeting of the Institute of Life Cycle Assessment, Kitakyushu, Japan, 5–7 March 2009; pp. 378–379. [Google Scholar]

- Itsubo, N.; Ii, R.; Morimoto, Y.; Horiguchi, K.; Yasui, M. Life cycle CO2 analysis for large-scale exhibition. J. Life Cycle Assess. Jpn. 2012, 8, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Release of Carbon Offset Report for G7 Ise-Shima Summit. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000199847.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Itsubo, N. Laboratory. Tokyo City University. Life Cycle Assessment for ILCAJ Meeting. Available online: http://www.comm.tcu.ac.jp/itsubo-lab/research/results/files/case/cs2009-b.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Ministry of the Environment Government of Japan. Environmentally Friendly Guidelines at Events (Premium Standards Development Guidelines Supplement). About Green Purchasing Law (reference). Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/policy/hozen/green/g-law/archive/pre/guide_201909.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020). (In Japanese).

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). MICE Economic Ripple Effect and Market Research Project Report 2016. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001186651.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). MICE Economic Ripple Effect and Market Research Project Report 2017. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/common/001233265.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Leontief, W.W. Input-Output Economics, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tahara, K. Development of inventory database for environmental hotspot analysis using IDEA. J. Life Cycle Assess. Jpn. 2019, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y. Estimation of 2011 waste input-output table for Japan. J. Life Cycle Assess. Jpn. 2019, 15, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y.; Ichisugi, Y.; Karkour, S.; Itsubo, N. Carbon footprint evaluation based on tourist consumption toward sustainable tourism in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO). International Conference Statistics 2016. Available online: https://mice.jnto.go.jp/documents/statistics.html#2016 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Events Industry Council (EIC). Global Economic Significance of Business Events. 2018. Available online: https://insights.eventscouncil.org/Portals/0/OE-EIC%20Global%20Meetings%20Significance%20%28FINAL%29%202018-11-09-2018.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). Global MICE City. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/shisaku/kokusai/mice.html#global (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Japan Tourism Agency (JTA). Promotion Policy at MICE. Available online: http://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/shisaku/kokusai/mice.html#promotion (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- New Chitose Airport Terminal Building Co., Ltd. News Release New Chitose Airport Portom Hall. Available online: http://www.new-chitose-airport.jp/ja/corporate/press/pdf/pdf-20190422_portom.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Toyota Motor Corporation. Zero Emission of Freight Transportation. Available online: https://global.toyota/jp/newsroom/corporate/24578176.html (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Hino Motors Ltd. Commercialize a New Trunk Transportation Scheme. Available online: https://www.hino.co.jp/corp/news/2019/20191204-002480.html (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Tinnish, S.M.; Mangal, S.M. Sustainable event marketing in the MICE Industry: A Theoretical Framework. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2012, 13, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organizer | Exhibitor | Participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic | Overseas | |||

| Plan | Planning and management (meetings and events, party, tourism program, post-convention held), administrative, venue usage, decoration and construction, equipment rental, shipping, printing, promotion and advertisement, extraordinary personnel, etc. | N | N | |

| Transp | International transport (flight) and domestic transport (flight, train, bus, taxi, gasoline etc.) | |||

| Acc | Accommodation | |||

| FB | Food and beverages | |||

| SE | N | N | Souvenirs and shopping Entertainment and tourism | |

| Stakeholders | M | I | C-ICCA | C-JNTO | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizer | 5.27 × 1010 | 2.70 × 1010 | 1.02 × 1010 | 1.50 × 1011 | 1.09 × 1010 |

| Exhibitor | N | N | 1.64 × 1010 | 5.16 × 1010 | 3.47 × 1010 |

| Domestic participants | 9.32 × 109 | N | 3.21 × 109 | 1.00 × 1011 | 2.09 × 1010 |

| Overseas participants | 1.62 × 1010 | 7.79 × 109 | 1.17 × 1010 | 5.81 × 1010 | 1.51 × 1010 |

| M | I | C-ICCA | C-JNTO | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (O) Domestic Transport | (O) International Transport | (OP) International Flights | (OP) International Flights | (OP) International Flights |

| 2 | (O) Accommodation | (O) Domestic Transport | (E) Shipping | (DP) Domestic Flight | (DP) Domestic Flight |

| 3 | (OP) Souvenirs and shopping | (OP) Souvenirs and shopping | (OP) Accommodation | (DP) Accommodation | (E) Shipping |

| 4 | (O) Food and beverages | (O) Accommodation | (DP) Domestic Flights | (O) Transportation of up to venue prefectures | (E) Conference decoration and construction |

| 5 | (DP) Souvenirs and shopping | (O) Food and beverages | (OP) Souvenirs and shopping | (O) Food and beverages | (DP) Train transport |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kitamura, Y.; Karkour, S.; Ichisugi, Y.; Itsubo, N. Carbon Footprint Evaluation of the Business Event Sector in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125001

Kitamura Y, Karkour S, Ichisugi Y, Itsubo N. Carbon Footprint Evaluation of the Business Event Sector in Japan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125001

Chicago/Turabian StyleKitamura, Yusuke, Selim Karkour, Yuki Ichisugi, and Norihiro Itsubo. 2020. "Carbon Footprint Evaluation of the Business Event Sector in Japan" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125001

APA StyleKitamura, Y., Karkour, S., Ichisugi, Y., & Itsubo, N. (2020). Carbon Footprint Evaluation of the Business Event Sector in Japan. Sustainability, 12(12), 5001. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125001