1. Introduction

An inclusive labor market, with equal opportunities for every individual, is a desideratum of all societies, and one of the Sustainable Development Goals established by the United Nations for the year 2030. Although the right to equal and non-discriminatory treatment is a right established by law in most countries, discrimination has deep roots in social norms—even in developed countries with a long legislative tradition in the field of discrimination.

Discrimination has many facets and many reasons, such as race, ethnicity, nationality—xenophobia, language, religion, beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, age, health or disability, social class, income. Discrimination in a work-related context is amongst the most important labor market issues, hampering labor market sustainability.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention regarding discrimination was signed in 1958, and currently, 175 states ratified it [

1]. The document specifies that everyone, regardless of race, creed or sex, has the right to spiritual development and material well-being in conditions of freedom, dignity, economic security and equal opportunities on the labor market, mentioning that discrimination is a violation of fundamental human rights [

2].

Discrimination at the workplace on the grounds of age, sex, disability, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation is prohibited in the European Union. In 2000, the European Union adopted two extremely important anti-discrimination directives: The Racial Equality Directive (2000/43/EC) and the Employment Equality Directive (2000/78/EC). Both directives had to be transposed into national law by 19 July 2003 and 2 December 2003, respectively in the EU Member States, while countries are entering in the EU after this date had to transpose both directives by the date of their accession [

3]. All citizens have the right to be treated equally in terms of salary, working conditions, hiring, promotion or dismissal criteria, access to vocational training programs. European Union legislation specifies several situations of discrimination: Direct discrimination—different treatment for comparable situations; indirect discrimination—company regulations or policies that have a negative effect on a group of people; harassment—inappropriate behavior that generates a hostile, degrading or intimidating work environment; victimization—negative consequences following the signaling of discrimination [

4].

The Romanian Anti-discrimination Law, namely, the Governmental Ordinance 137/2000, was adopted in 2000 as delegated legislation and has subsequently been amended [

5]. In addition to the Anti-discrimination Law, some other Codes specify other aspects regarding discriminatory situations (e.g., the Civil Code denounces claims in the case of damage—including damages generated by discrimination); the Criminal Code includes measures on aggravating circumstances when criminal intention is caused by any of the reasons protected by anti-discrimination legislation; the Labor Code includes general prohibitions of discrimination in employment). The same law (GO 137/2000) decided for the setup of the national equality body, the National Council on Combating Discrimination (NCCD) which was effectively established in the autumn of 2002.

Over time, and especially in the context of globalization, population diversity has been influenced by socioeconomic, political, environmental, and technological factors. Changes in society translate into changes in the way people interact, cohabit, or work together. Migration has also contributed significantly to these changes, as the socio-cultural dimension has been directly influenced by the different background and specific lifestyles of migrants. This dynamic has also left its mark on the labor market, because this diversification challenges workers’ perception of different personal characteristics (race, language, ethnicity, gender, age, disability, traditions, religion) of colleagues/superiors/subordinates at work. The positive aspects of diversity in the workplace are related to organizational culture: a tolerant environment is promoted, focused on problem-solving, critical thinking and professional skills development, companies being focused on attracting talented, creative people, with high productivity. On the other hand, these benefits can be hindered by the hostility and discrimination that certain people sometimes face in the workplace, diversity not always being easily accepted by all workers [

6]. In such companies, the management is particularly important—mediation skills are needed, the communication must be encouraged, and any act of discrimination must be penalized. However, it has been observed that there is a high cost of managing workforce diversity [

7]. Green et al. [

8] concluded that a good knowledge of workplace legislation can help reduce the tendency to discriminate.

Discrimination in the labor market can negatively affect the performance of an economy. Discrimination hurts global productivity by excluding some workers from the labor market and not making the most of their potential. Moreover, studies have shown that labor market discrimination is associated with reduced economic growth and higher unemployment rates [

9,

10]. In the European Union, the disadvantaged position of women on the labor market was studied, and the results showed that this situation generates economic inefficiency and that greater involvement of women in the labor market would be a competitive advantage [

11].

On the other hand, especially in developing countries, discrimination has a strong impact on the living standards of individuals: Discriminated people are forced to accept poorly paid, unsafe and difficult jobs, often becoming victims of harassment or violence, and their opportunities for professional development, training or promotion are much lower [

12]. Equal and full access to employment is essential for promoting social inclusion and combating poverty. Employment is not only a source of income that determines material well-being, but also an incentive to build human capital, a solid foundation that allows the formation of survival strategies and relationships between groups and society as a whole.

In Romania, the annual report of the National Council for Combating Discrimination (NCCD) from 2019 presents an interesting image of discrimination—386 petitions regarding social class, 87 petitions regarding disability, and 80 regarding nationality. Out of more than 1000 cases solved in 2019, 432 were related to work situations (around 40%). Of the 432 settled cases in 2019, NCCD reported 360 on social class criteria, 16 on age, 15 on gender, 11 on disability, 11 on nationality and ethnicity [

13]. Regarding discrimination in the labor market, a survey revealed that people infected with HIV have the lowest chances of access to the labor market, for Roma people, it is more difficult to find a job (62% of respondents designated Roma as the most disadvantaged ethnic category when it comes to employment), and rural area residents seem to be disadvantaged in the employment process compared to those in urban areas [

14]. A study for Eurofound mentioned that the gender pay gap in Romania was 5.2% in 2016 [

15], above the EU average. Still, it is argued that this figure might be too low, because very few women with primary and secondary education are employed, and in the end, the comparison is made between highly educated women’s wage and low educated men’s wage.

In this context, this paper aims to investigate the perception of Romanians regarding the labor market discrimination, as it still is a phenomenon which affects labor market inclusiveness and hinders the efforts towards a more sustainable labor market. The analysis is based on survey data, gathered at the end of 2019. Besides the perception of individuals regarding discrimination in general, we tried to capture the characteristics of the individuals who feel discriminated in Romania in a work-related context.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the literature review regarding discrimination in the labor market,

Section 3 describes the data and the methods used in the study,

Section 4 presents the statistical analysis and the econometric results, and the final section is dedicated to discussions and main conclusions.

2. Literature Review

The problem of evaluating the presence, measure, type and evolution of discrimination in various contexts has been a topic of interest for a long time, discrimination being investigated from several perspectives: The legal dimension, the social, as well as the economic one.

Discrimination in the labor market takes the form of a difference in attitude, behavior or treatment in terms of pay (wage differentials), labor market participation, occupational segregation, access to vocational training, working conditions, and criteria for employment or dismissal.

Empirical research in the field of labor market discrimination usually applies statistical inference techniques to data sets with two possible purposes: (i) Testing the consequences of discrimination described by various theoretical economic models, or (ii) evaluating the contribution of different types of discrimination to different treatments on the labor market [

16]. The most commonly used methods of discrimination analysis are statistical tests for means and proportions, linear (generalized or logistic) regression models and other econometric models. For example, in the USA for legal situations, the discrimination in hiring or promotion is proved using logistic regression models, although, alternatively, the Peters-Belson regression method can be used [

17].

From a theoretical point of view, two major economic models of discrimination are considered in the literature. The taste-based discrimination model proposed by Becker [

18] considers that discrimination is based on personal preferences, and hence, the tendency to disregard certain groups. Wage differences would be due to an additional psychological cost of hiring certain groups of workers. The central hypothesis in the statistical discrimination model, described by Arrow [

19] and Phelps [

20], is that employers cannot assess workers’ productivity at the exact moment of hiring, so they use certain observable personal characteristics (sex, race, age, etc.) to estimate the productivity of those workers, based on their previous experience and general knowledge of the productivity of a particular group of workers. The wage differences come from the fact that the initial salary is fixed according to the expected productivity and not according to the real productivity of the individual.

Despite all efforts to reduce it, discrimination against minorities is still very much present in many societies. In the United States, research has established quite clearly the persistence of vulnerabilities and inequalities in employment, mobility, wages and dismissals for workers belonging to minorities, despite the existence of civil rights protection for over 50 years [

21]. The impact of discrimination on immigrant workers was studied by Larsen and Waisman [

22] using a search and wage-bargaining model, their results indicating high unemployment rates, lower wages, and lower productivity jobs among immigrants in the US. Wilson and Rodgers [

23] analyzed the black-white earning differentials taking into account several socio-demographic control variables like age, gender, education, or residency and observed that discrimination explains an important part of the wage gap.

In Europe, the Roma are the largest ethnic minority and have been an integral part of European society for centuries. However, despite efforts at national, European and international level to improve the protection of their fundamental rights and promote their social inclusion, many Roma continue to face severe poverty, deep social exclusion, and discrimination [

24]. In the Czech Republic, the Roma experience severe discrimination that influences their labor market outcomes or opportunities, as pointed out by O’Higgings and Bruggemann [

25] following an analysis based on non-parametric matching models.

In Denmark, UK and Spain many immigrants and ethnic minorities are overqualified; in Germany, Poland and Cyprus migrant workers have significantly lower wages than the natives; in Estonia, Spain and Ireland many racist incidents were registered, the victims being in most cases Muslims and Africans; in Hungary and Romania the most discriminated group is Roma, and in France the African women register the lowest value for labor force participation rate [

26]. In a comparative analysis of migrants versus non-migrant employees in UK, Italy, Spain and Germany, the results indicated that migrants have a lower level of skills coming from less training opportunities and skills depreciation [

27].

In the UK, racism is a very persistent phenomenon—the most common forms being the islamophobia, the antisemitism, but also anti-Black and anti-Asian racism. Discrimination against ethnic minorities is frequent in the labor market: Thirty-two percent of the employees belonging to this vulnerable group experienced harassment or bullying at the workplace [

28].

A common method of testing discrimination against ethnic minorities was initiated by Bertrand and Mullainathan [

29] who used CVs with traditional White and African American names. They observed that the callback rate is 50% lower for the African Americans, therefore demonstrating the discrimination. The same methodology was employed in other studies, conducted in Canada [

30], France [

31], and Sweden [

32], all with similar results.

Di Stasio et al. [

33] analyzed Muslim discrimination in five European countries (Germany, Spain, UK, Norway and the Netherlands) and found a high level of discrimination against this group, especially against Muslim men, Norway being characterized by a pronounced disadvantage of Muslims on the labor market.

Another cross-country study focused on Germany, the United Kingdom, Norway, the Netherlands, Spain and the United States and used 19,181 respondents, covering 53 ethnic minorities in order to analyze labor market discrimination. The results highlighted the persistence of discrimination against these groups, but the magnitude is not the same in all analyzed countries—it correlates with cultural differences; therefore, the most discriminated group is the one furthest from the social beliefs of the majority [

34].

Based on the relative deprivation theory, Triana et al. [

35] analyzed the relation between the perception of gender discrimination and the employees’ results at work using 85 studies for several countries. The results pointed out a negative relationship between the employees’ perceived gender discrimination and job attitude, health, behavior, as well as work socialization or results. The correlation was stronger in the countries where discrimination was treated more carefully, with an emphasis on labor relations that respect gender equality.

Gender discrimination in hiring was investigated by Yavorsky [

36] using 6302 CVs and analyzing 3156 jobs, focusing on two categories of jobs: Masculine-type and feminine-type. The main results indicated that discrimination against women is much more common, although discrimination against men occurs in feminine domains. However, women are the ones discriminated against when it comes to jobs in white-collar occupations.

A comprehensive study analyzed discrimination against women using data for the period 1994–2012, for 51,632 individuals in 18 countries [

37]. Using several structural equation models for the entire sample, as well as for every country, they confirmed that women experience discrimination in the labor market, especially on the topic of career development after giving birth. Moreover, the authors found that in the countries with reduced gender inequalities, people are generally in favor of women participating on the labor market, but only a small share of the respondents were in favor of gender equality in the household.

Regarding transgender and gender non-conforming people, Grant et al. [

38] documented strong discrimination, over 90% of the respondents included in their study, stating that they were discriminated against at work. On the same topic, Rosich [

39] obtained that 67% of transgender and gender non-conforming people faced discrimination at the workplace, transmen being more likely to experience to a greater extent and more types of discrimination than transwomen.

The access and problems of people with disabilities in the labor market is also a topic of interest for researchers. Doyle [

40] conducted a comparative study of the legislative framework that protects the rights of people with disabilities in the labor market, considering the situation in the UK versus Australia, Canada, the European Union and the United States. Moreover, the situation of people with disabilities on the labor market, as well as their standard of living in the UK, by comparison with Germany and Sweden was later studied by Barnes [

41]. Using a survey analysis, Shier et al. [

42] investigated the barriers to employment faced by disabled people in Canada. Yazici et al. [

43] interviewed 421 disabled employees from Turkey and used logistic regression models in order to analyze their job satisfaction. For Australia, Temple et al. [

44] analyzed discrimination and avoidance behavior regarding people with disabilities, their results indicating that around 9% of people with disability faced discrimination and 31% observed avoidance behaviors towards their disability, those with visible physical disabilities being more likely to be discriminated against.

Concerning discrimination based on educational attainment, it is often ignored in studies, mainly because differentiation between individuals on the grounds of merit and qualifications is not regarded as discrimination. Still, discrimination based on educational attainment exists, and it is usually encountered together with other types of discrimination, such as race, gender and class [

45].

Age discrimination is manifested mainly in two vulnerable groups: Young people and people close to retirement age. Widespread perceptions and beliefs exacerbate age discrimination among the population, especially related to the physical and cognitive abilities of workers at a certain age. Young people are considered to be involved in the transitions from childhood to adulthood, from education to work and from dependency to autonomy. Discrimination, both individual and structural, prevents the effective implementation of these transitions [

46].

On the other side of the age distribution, older people have difficulty both keeping and finding a job due to age discrimination. Once unemployed, they are disproportionately faced with long-term unemployment compared to younger workers. Age discrimination against the elderly is primarily influenced by the concept that an individual’s physical and mental capacity is adversely affected by aging. “Gray ceiling” is a term often used to describe discrimination on the grounds of old age. In the labor market, in addition to being considered “old”, experienced candidates are sometimes considered to generate greater expenses (higher salary, pension, social security costs, etc.) than a younger candidate [

47].

Although most discrimination studies usually focus on a specific reason or a particular aspect, Roscigno [

48] analyzed discrimination in a sample of 6000 workers in the United States on several grounds and at several hierarchical levels. The results indicated that gender, age and ethnic discrimination still are a severe issue, gender and age discrimination being more often found in higher professional positions, while sexual harassment experienced by women and racial discrimination being experienced at all hierarchical levels.

For Romania, studies in the field of discrimination focus mainly on the Roma population, the second largest minority in Romania. According to the latest census, the Roma population represents 3.3% of the total, but expert estimates place the Roma population between 6% and 12% of the total population of Romania, becoming practically the main ethnic minority [

49]. The main aspects investigated in the literature are the risk of poverty, severe material deprivation, employment rate, the share of the Roma population with higher education. Discrimination in the labor market prevents Roma from fully participating in society by reducing opportunities and aspirations. Low labor market opportunities, outdated traditional occupations, cultural patterns and discrimination are all contributing to the social marginalization of Roma.

The results of a survey conducted for the National Council for Combating Discrimination showed that 46% of respondents do not feel comfortable around a Roma person, 46% consider that Roma are lazy, 45% consider them aggressive and 35% dishonest; the most important areas in which discrimination against Roma is manifested are: employment, access to public services, medical services, legal services, or within educational institutions [

50]. In relation to the labor market, Munteanu [

51] analyzed the policies in the field of employment meant to integrate and support young Roma in rural areas, both public and those carried out by non-governmental organizations. Rus and Nestian-Sandu [

52] studied discrimination and social inclusion of Roma, but also their relationship with the labor market from the perspective of both employees and employers, using qualitative and quantitative methods.

Other issues covered by the specialized studies in Romania were gender discrimination or the analysis of discrimination against people with disabilities. Turturean et al. [

53] analyzed gender discrimination in the Romanian labor market from an economic point of view in the period 1990–2011 taking into account the employment rate, unemployment rate, income level and retirement period, the results indicating statistically significant advantages in favor of men. Țițan [

54], using survey data, analyzed discrimination in the Romanian labor market, over 70% of respondents indicating the existence of this phenomenon and documenting at the same time the presence of earnings inequalities between women and men, between rural and urban, among those in multinational companies versus other types of companies.

A United Nations study looked at gender discrimination and inequalities between women and men with a focus on public sector employment. The results indicated that professional life policies do not currently encourage the equitable sharing of private and family responsibilities between women and men. Gender roles performed in the household by women are translated into public administration jobs—more women work in “female sectors”, such as health and education and enjoy less power, less prestige, and lower wages [

55].

Disability is one of the most important characteristics of a person that generates vulnerabilities, having the potential to expose the person, at the same time, to poverty, discrimination or abuse. Baciu et al. [

56] analyzed the obstacles faced by people with disabilities in the labor market, as well as the discrimination they face in finding a job or accessing educational and medical services, the results indicating a very low employment rate for the persons with disabilities in Romania, discrimination being an important barrier to employment. Birau et al. [

57] analyzed the relationship between social exclusion and integration on the labor market for people with disabilities and pointed out the main difficulties faced by the disabled: Poor infrastructure and discrimination, even reaching social stigma. Moreover, they observed reluctance among employers in hiring people with disabilities as they have to adapt the workplace to their specific needs. A qualitative approach to study the social inclusion and integration of people with disabilities in the labor market was used, the results indicating that the current protection system is fragmented and deficient and fails to combat the many negative aspects associated with disabilities in Romania: poverty, low level of education, high unemployment rate, and discrimination [

58].

3. Data and Methodology

In a research conducted by INCSMPS (National Scientific Research Institute for Labor and Social Protection) national representative data were collected through a survey, during the period October–November 2019. The survey was conducted by CURS Romania (Center for Urban and Regional Sociology), an organization which is accredited (by the National Supervisory Authority for Personal Data Processing) for operating and processing personal data. The organization follows all the legal requirements in place, and personal data collection procedure complies with Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons concerning the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Therefore, the organization pays special attention to the protection of data, ensuring all appropriate technical and organizational measures to maintain an adequate level of data security.

Potential respondents were informed that their personal data (name, address) is registered solely for the verification of data collection quality and that the information provided by them is registered and processed following statistical procedures. In contrast, their further identification by the researchers who process the data would not be possible. The consent of the potential respondents was sought with regards to personal data registration and processing. Respondents were also informed on their rights to access, rectify, delete or restrict personal data processing or withdraw their given consent concerning personal data processing at any moment. Participation in the survey was on a voluntary basis, and anonymity of respondents has been ensured, so that the researchers of INCSMPS (National Scientific Research Institute for Labor and Social Protection) who have processed the collected data did not receive any information that could identify the respondents.

The sample for the questionnaire was selected from the resident population in Romania, aged 18 and over. In the end, 850 individuals responded to the face-to-face interview, and the maximum error for the whole sample being ±3.4% at a confidence level of 95%. The sampling was probabilistic, multistage and stratified.

The questionnaire aimed to investigate the opinion of the individuals regarding inequality, discrimination and vulnerability. The design of the questionnaire has been done following the investigation of a wide specialized literature; it is worth mentioning two references that may be considered a starting point in the design of our questionnaire [

59,

60]. The instrument has been pre-tested being run on a small scale, and following this, certain questions have been reworded to ensure a better understanding; also certain questions have been changed from open-ended to closed in order to adapt to the ability of the respondents to express their perceptions and feelings towards the sensitive issues concerning discrimination and inequalities.

But for this analysis, we focused on the perceptions of individuals regarding discrimination at work. In order to capture the relevant aspects, we turned to descriptive analysis and regression.

Along with the perception of individuals regarding discrimination in general, and at work in particular, we tried to capture the general characteristics of those individuals who feel discriminated in Romania, with focus on gender, age, residency, ethnicity, education, income, household characteristics. As for the regression analysis, the aim was to unfold the characteristics that best describe the individual profile with higher chances to be discriminated in a work-related context. Therefore, we considered relevant to choose as the dependent variable the individual perception of being discriminated against in a work-related context or not.

Being a binary variable, which typically takes the value of 0 for a negative outcome (the event did not occur) and 1 for a positive outcome (the event did occur), the best-suited regression model, in this case, is the logistic regression (or the logit model) [

61]. This type of model allows us to explore how each explanatory variable affects the probability of the event occurring. In this particular case, the dependent variable takes value 1 if the individual admitted that he was discriminated in a work-related situation and 0 if not.

The logistic model is a single-period classification model for which estimates are based on a maximum likelihood function in order to determine the conditional probability of a subject belonging to a category based on several independent variables [

62]. The logit model describes the relationship between the binary variable Y and k explanatory variables X

1, X

2, …, X

k.

Having the linear probability model as a starting point:

then, if the probabilities are restricted to be in the [0, 1] range, the following model is obtained:

Applying logarithms to these probabilities, the logit model is obtained:

The last relationship is known under the name of logit form of the model, where lnΩ(x) is the logarithm of the probability for an individual to be part of one category in relation to the explanatory variables Xi1, Xi2, …, Xik. Accordingly, in the logit model, the log-odds of the outcome are modelled as a linear combination of the predictor variables.

In general, to obtain the odds ratios (OR), one should calculate the exponential of the coefficient β:

The odds ratios are preferred when interpreting the results of logistic regression as they represent the effect of an explanatory variable X on the likelihood that the analyzed outcome will occur. In our analysis, we are interested in obtaining the odds ratios to see if an individual is more likely to be discriminated in a work-related situation, depending on specific socio-demographic characteristics.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Some of the general characteristics of the respondents are presented in

Table 1. As can be seen, 57.2% of the individuals participating in the survey are female, while 56.5% are living in urban areas in Romania. As for the ethnicity, the vast majority are Romanian (91.3%), followed by the Hungarian (6.4%) and Roma (1.3%).

Regarding the marital status, 2 in 3 respondents were either married or in a relationship, and only 1 in 10 respondents were unmarried. Although the questionnaire comprised a detailed list for education levels, we decided to report in the descriptive analysis only four main categories: early or no education (ISCED 0), primary and lower secondary education (ISCED 1–2); upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education (ISCED 3–4); tertiary education (ISCED 5–8). Most of our respondents are in the third category (ISCED 3–4: 60.2%).

As for some household characteristics, we choose the size and the social class. For the household size, we grouped the responses into several categories: Households with one member, with two members, with three or four members, or with five or more members. One in three respondents is part of a family of three or four persons, and another 34.2% is part of a two-person household. More than half of the respondents placed themselves in the middle class (58.6%), and one in three considers that s/he belongs to the lower class. Only about 2% appreciate that they belong to the upper class.

In addition to these characteristics, we considered useful to analyze the occupational status, the ownership of the company in which they are working and their position in the company. The majority of the respondents declared that they are employees (41.5%), while an additional 3.4% are self-employed (inclusive employers). About one in three individuals are retired, and only 3.6% declared that they had no job. Two thirds of the employees or self-employed/employers are working in a private company, while almost 86% have an execution position.

Asked about the areas in which discrimination is widespread in Romania, the first option for the majority of respondents (74%) indicated the context of “work and employment” (

Figure 1a). The question offered the possibility for multiple responses, therefore adding all answers together we obtained the complete picture of the perceptions regarding the discrimination in Romania. The second and third areas in which discrimination is considered to be widespread are “education” (44%) and “healthcare” (43%). As for who discriminates (

Figure 1b), 71% of the respondents pointed out to “people in general”. Adding all answers together (the question offered the possibility for three options per respondent), we obtained that almost one in two respondents considers that private employers are discriminating, while 40% perceive the state institutions as discriminatory.

Whether an employee identifies a behavior as discriminatory or not depends on that individual: Some discrimination behavior will go unnoticed, while some non-discriminatory behavior may be perceived as discriminatory [

63]. This correct identification depends on multiple aspects, like: awareness of discrimination issues, age, education, social class, gender. Still, perceived discrimination (reflecting or not actual discrimination) is important. Previous research has found that it affects individual and group behavior in the workplace, including by reducing pro-social behavior [

64,

65].

Therefore, the respondents were asked directly if they were discriminated in any manner in the last year, even though it is a subjective evaluation. The responses are presented in

Figure 2a. More than two thirds declared that they had not been the subject to discrimination in the last year. Still, 7.8% declared that they suffered a discriminatory action once, and 6.4% suffered a discriminatory action more than once. Regarding the individuals declaring that they have been the subject to discrimination in the last year in a work-related context (

Figure 2b), 13.3% indicated ethnicity as a reason for discrimination. Another 12.5% mentioned income level and 10% age. More than half of those individuals having admitted to suffering from discrimination in a work-related context did not choose any of the categories presented, nor did they indicate another.

If we look more deeply into the responses, we discover that two out of three respondents accusing gender discrimination are females. Only one in four individuals accusing ethnic discrimination declared himself Roma people, while 44% of them are Romanians. Two in three individuals accusing age discrimination are in the 50–64 age group. Regarding income level, it appears that half of the individuals who reported that they had felt discrimination due to their income level, also declared that their family earnt enough to cover living costs, with some extra expenses.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the individuals discriminated in a work-related context (or more). They represent around 14% of the total respondents participating in the survey. There are more women than men and more city residents than villagers. As the ethnicity concerns, 4.2% of the individuals that were discriminated in the last year are Roma, the Hungarians represent 5%, while the Romanians 87.5%. In terms of incidence, as everyone would expect, the Roma are more discriminated, with 45% of them being found in this situation.

More than half have completed an ISCED 4 level of education and are part of the middle and upper class according to their subjective assessment (the upper class only accounts for less than 1%). However, in terms of incidence, it can be seen that in the group of the highly educated individuals, one in five declared that s/he was discriminated in a work-related context in the last year.

14.3% of the individuals who had at least one discrimination experience are in a managing position, but the vast majority of the discriminated individuals have an execution position. Two in three discriminated individuals in a work-related situation are working in a private institution. Regarding the age, one in three discriminated persons is in the 35–49 years age group and almost the same proportion in the 50–64 years age group. As for the family characteristics, more than two thirds are married or in a relationship; 30.8% are part of a family with two members and 40% belong in a household with three or four members. In addition, we note a high incidence of self-perceived discrimination in the case of individuals belonging to households with numerous members (more than four people), around 20% of them invoking personal experiences of work-related discrimination.

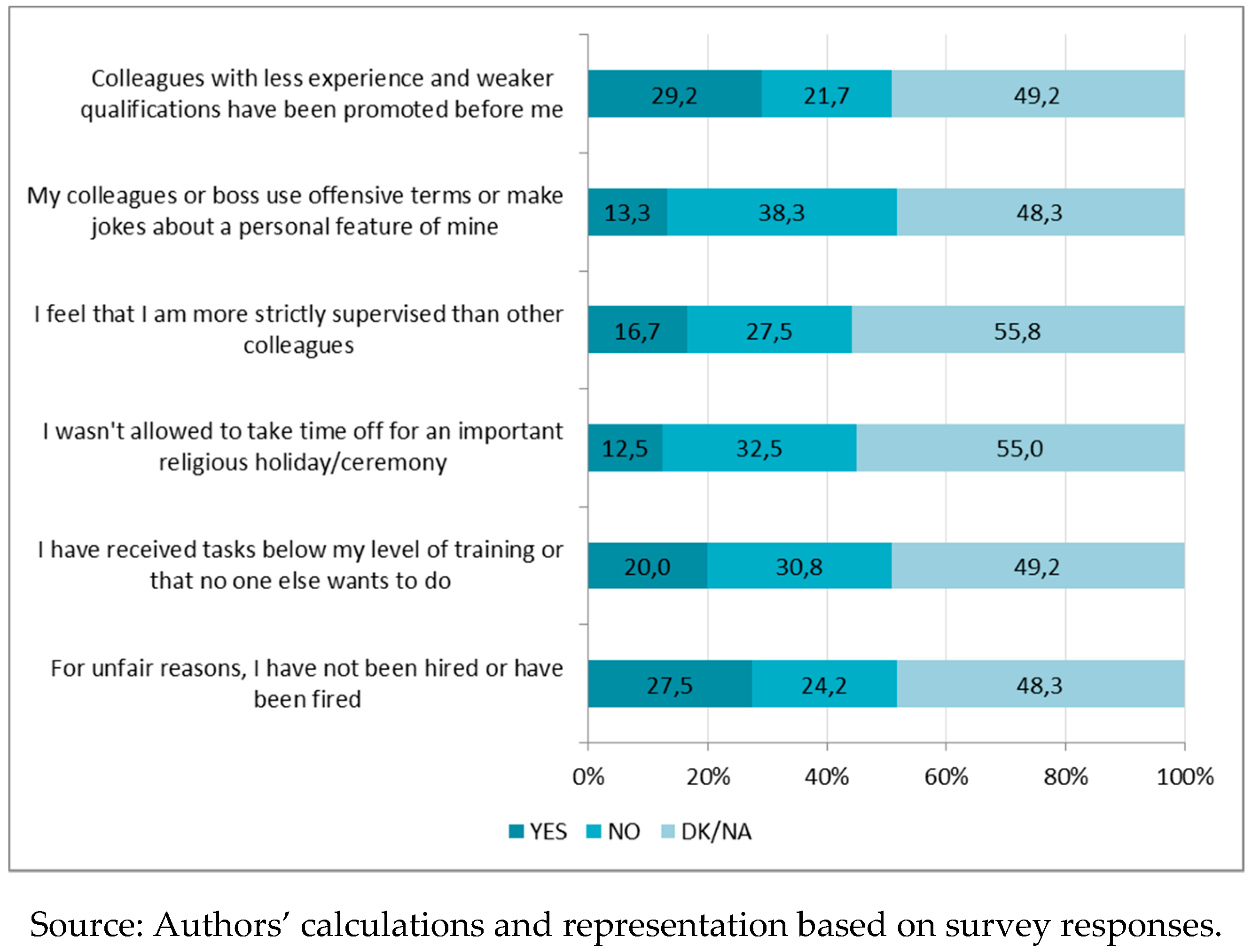

Questioned about the discriminatory situations that may arise at the workplace, the most encountered seems to be the one in which colleagues with less experience and weaker qualifications have been promoted before the respondents: Almost one in three had to face such situation (

Figure 3). Another discriminatory situation that gathered several answers (around 27%) was the one in which the respondents have not been employed or have been fired, for reasons perceived as unfair. One in five discriminated individuals received tasks below their level of training or that no one else wants to do. In most cases, at most half took action against discrimination, and the most widely used measure was to “talk to superiors”. Those who did not take any action in perceived discriminatory situations, argued that things would not have changed at all or even considered that was not necessary to act, while some were afraid that their situation would get worse.

None of the respondents selected the option “I opened a private lawsuit/I filed a complaint with a lawyer”. Unfortunately, about half of the discriminated individuals did not responded to these questions, which may have hampered a more rigorous analysis.

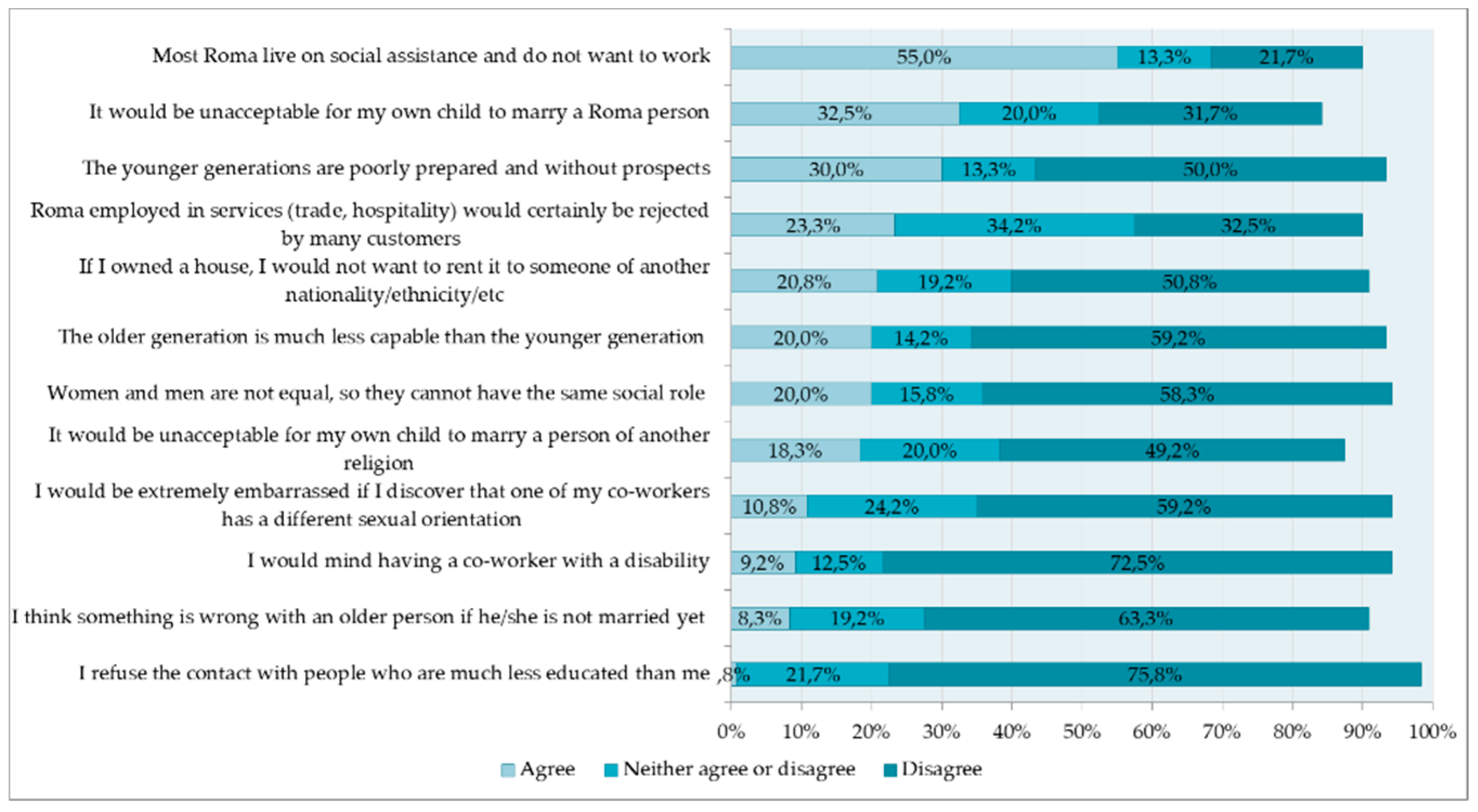

Some interesting aspects were revealed through the correlation between the answers of those individuals who perceived to be discriminated in the last year, in a work-related situation to a series of statements identifying stereotypes and prejudices (

Figure 4). Out of the individuals perceiving discrimination in work-related situations, 55% agree with the statement that “Roma people live on social assistance and they do not want to work”. In addition, 32.5% considers “inacceptable that their own children to be married to a Roma person”. The results also show that almost one quarter of the discriminated individuals agrees with the statement according to which “the Roma employed in service activities would certainly be refused by many clients”. Regarding age stereotypes, we can see that almost one in three respondents previously found in situations of discrimination considers that “the Young are poorly trained and without perspectives”, while one in five believes that “the Old generation is less capable than the Young generation”. For the former statement, we have 42% agreement among the discriminated persons in the 65+ years age group. For the latter statement, 26.4% of the individuals in the 18–34 years age group and 24.3% of those in the 50–64 age group expressed their agreement.

One more interesting aspect is that one in five discriminated individuals agrees that “women and men are not equal, and therefore, they cannot have the same social role”. The very interesting aspect comes from the fact that out of the individuals that agreed with the statement, 62.5% of them are women. Overall, the above findings bring proof on the link between stereotypes, prejudices and discrimination, and more, they show that those who felt themselves discriminated are, at their turn, adopting stereotypes and prejudices under two forms: They are antagonistic to other groups (young against elderly, Romanians against Roma ethnics, etc.), or they project stereotypes and prejudices that others create onto themselves. This behavior reinforces and perpetuates discrimination.

4.2. Econometric Analysis

We selected several characteristics to explore how each of them affects the probability of an individual to be discriminated in a work-related context. Regarding the personal characteristics of the individuals, we worked with: Gender (male/female), residence area (urban/rural) and age. The former are, by default, 0/1 variables, with 1 for men and 0 for women, and 1 for urban areas and 0 for rural areas, respectively. As for the latter, even if the survey collected the exact age of the individuals, we decided to use the following age intervals: 18–34 years, 35–49 years, 50–64 years and over 65 years. Based on these four groups, we constructed four dummy variables—each taking value 1 if the respondent is aged within that interval and 0 if not. For the logistic regression models, when using such categorical variables transformed into dummy variables, one is excluded from the model, and the results are analyzed according to this excluded variable (in this case, we excluded the 35–49 age interval). For the education level, we constructed three dummy variables, one for each category: ISCED 0–2, ISCED 3–4 and ISCED 5–8. The basis for comparison in the regression was the last one.

For the social class, we grouped together with the middle and the upper class, while for the household dimension we grouped together families with one or two members in a category, and the other families in another category. Regarding ethnicity and marital status, we considered the previously mentioned categories. Again, for the logit model, we transformed each variable into a set of dummy variables constructed on the same principle as those relating to age (the dummy takes the value of 1 if the individual belongs to that category, and 0 if not). The basis for comparison in each case was selected accordingly.

Another category of explanatory variable considered in the logit model was the income, expressed through exact personal income, for which we constructed three dummy variables, for each of the following income intervals: No income up to the minimum wage in November 2019 (1263 Lei), between the minimum wage and the medium wage (which was 3179 Lei in the same month), above the medium wage (the values presented are the net values).

The general form of the estimated model was:

Regarding the ethnicity, it appears that the coefficient for the Hungarian ethnic group is not significant, but the ones for Roma people and for other ethnic groups are. So, according to our results, Roma people have 6.7 times higher chances to be discriminated in a work-related context as compared to a Romanian individual (

Table 3). Individuals from other ethnic groups have even more chances to be discriminated (682.7% more chances as compared to Romanian individuals).

We tested for the significance of discrimination by educational level. Taking into account the level of education variable, the results confirmed that both coefficients, corresponding to low and medium levels of education are statistically significant. Our results indicate that individuals with at most secondary education have 67.5% fewer chances to find themselves in a discrimination situation. In comparison, the individuals with at most high school diploma have 49.4% fewer chances to feel discriminated as compared with highly trained individuals (ISCED level 5+). However, the results are just the opposite to what we expected, showing that individuals with higher education perceive themselves discriminated on the labor market to a greater extent than low and medium educated persons.

There are studies which support the idea that educational attainment constitutes the grounds for discrimination most frequently combined with other individual traits, such as gender or ethnicity [

45]. Following these beliefs, we have tested the incidence of self-perceived discrimination at the intersection of educational level and gender, and it appears to have relevance. Only one category (higher educated men) had statistical significance, but we considered the entire result to be important. Low-educated men have 2.13 times higher chances to be discriminated as compared to women with the same education. Instead, males with medium education have 0.86 times fewer chances to be discriminated, or in other words, females with medium education have 1.15 times higher chances to be discriminated. As already mentioned, the same goes for the highly educated men, which have 70% fewer chances to be discriminated in a work-related context as compared to females with the same education. So, it seems that at lower levels of education, men are more likely to perceive work-related discrimination than women, while women with medium or higher education have more chances to feel discriminated than men within the same level of education. We mention that, interestingly, we did not find relevant proof of gender discrimination, except when combined with the level of education.

Age, on the other hand, appears to be statistically significant for only one category: The one associated with 18–34 years age group. Individuals in this group have fewer chances to be discriminated as compared with the individuals in the 35–49 years group. The same goes for the other age groups, but the results, in their case, are not statistically significant at 10%.

The results of the logistic regression indicated that there are no significant differences in terms of discrimination in a work-related situation depending on the personal income, social class, marital status or household size.

5. Discussions

The United Nations consider equality and non-discrimination to be the core of sustainable development. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is centered on equality, all goals stating that more equitable development leads to the sustainable development of all people. Special attention is paid to these issues because inequality and discrimination cause social unrest, threaten social progress and affect human rights [

66]. The 2030 Agenda brings back to the forefront the responsibility of each Member State to “respect, protect and promote human rights, without distinction of any kind as to race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinions, national and social origin, property, birth, disability or other status” [

67]. There are two dedicated goals on combating inequality and discrimination: Goal 5 on achieving gender equality and Goal 10 on reducing inequalities within and between States. At European Union level, sustainable development is seen as having three interlinked and equal dimensions: economic, social, and environmental. Following the 2030 Agenda, the European Pillar of Social Rights comes to offer prominence and visibility to the social dimension of sustainability [

68]. Measuring social sustainability is not an easy job, but it has commonly been assessed through several indicators of labor market and social outcomes. These dimensions are interconnected, an example being the labor market which is considered an important component of sustainable economic development, while also having an impact on social development [

69].

Discrimination has a strong impact on the living standards of individuals, while discrimination in the labor market can hamper human development, negatively affecting the economic performance of a country. Discrimination can take many forms, based on many reasons: race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, age, health or disability, social class, educational attainment, income. Despite all efforts to reduce it, discrimination is still very much present in many societies, even the more advanced ones. Self-perceived work-related discrimination can reduce motivation for job searching or work performances, could also affect the working environment. Likewise, it can be harmful to physical and mental health, and to further professional development as well.

In our paper, the analysis of the characteristics of the individuals who felt discriminated in a work-related context revealed some important facts: Around 14% of the total respondents participating in the survey faced a discriminatory situation in a work-related context during the last year; among them, there are more women than men and more city residents than villagers; almost half of the Roma included in the survey experienced discrimination; more than half have completed either high school or post-secondary education and are part of the middle and upper class; one in three discriminated persons were within the 35–49 years age group, with almost the same proportion in the 50–64 years age group; and two in three discriminated individual were working in a private institution.

Our results agree with the official information from NCCD: The principal field in which discrimination occurs is the work and employment area, as 74% of the respondents with personal experience of discrimination mentioned in the survey. As for who discriminates, 71% of the respondents pointed out to the people in general, and only after adding all answers together, we obtained that almost one in two respondents considers that private employers are discriminating. In comparison, 40% perceive the state institutions as discriminatory.

Regarding the concrete situations of discrimination, the most encountered seems to be the one in which colleagues with less experience and weaker qualifications have been promoted before the respondents (almost one in three had to face such situation). Other discriminatory situations reported by respondents were: s/he has not been employed or had been fired, for reasons perceived as unfair (nearly one in three cases); s/he received tasks below its level of training or that no one else wants to do (one in four cases). Unfortunately, there are more individuals who have not taken any action than those who have done something against the act of discrimination they experienced. The most used measure we found is “Talking to superiors”, while none of the respondents opened a private lawsuit or filed a complaint with a lawyer. Most did not take any action believing that nothing would have changed even if they had done something.

The logistic regression revealed some interesting aspects. Regarding the ethnicity, it appears that Roma people and other ethnic groups are more likely to be discriminated in a work-related context as compared to a Romanian individual. These results agree with similar studies that showed that discrimination is highly present among minorities, and particularly among Roma people in the Eastern European countries [

25].

Taking into account the level of education variable, the results are just the opposite to what we expected, showing that individuals with higher education perceive themselves discriminated on the labor market to a greater extent than low and medium educated persons. This could be explained by the fact that personal experiences of higher educated people in the area of work-related discrimination are more likely to occur because the competition for being hired or promoted is stronger for better quality jobs. These findings are in line with those of previous research, such as Roscigno [

48].

Considering the studies which support the idea that educational attainment constitutes the grounds for discrimination most frequently combined with other individual traits, such as gender or ethnicity [

45], we also tested the incidence of self-perceived discrimination at the intersection of educational level and gender. Our results indicate that highly educated men have 70% fewer chances to be discriminated in a work-related context as compared to females with the same education.

Age, on the other hand, appears to be statistically significant for only one category: The one associated with 18–34 years age group. Individuals in this group have fewer chances to be discriminated as compared with the individuals in the 35–49 years group. The same goes for the other age groups, but the results, in their case, are not statistically significant at 10%.

Our research contributes to knowledge development in the field of discrimination in general, and self-perceived discrimination in a work-related situation, in particular. This study provides new evidence that supports similar findings from previous studies regarding the Romanian context (such as the incidence of discrimination among Roma). Moreover, this study also initiates a move in a new direction for research within the area of discrimination in Romania, by showing that educational attainment is relevant for work-related discrimination experiences, alone or combined with gender.

Regarding the main limitations of our research, we must mention the following. First, our survey was not designed to be representative of all socio-demographic categories, therefore certain categories are under- or over-represented in the database. Second, the self-perceived measure of discrimination could be further refined in order to increase the response rates for the questions that evaluate the perception of personal experiences concerning discrimination. Third, based on the relevant literature, we believe that income level or social class may be factors of discrimination, but difficulties in collecting valid income data (and even the self-assessment of social class) are a limitation for our findings.