2. Theoretical Framework and Literature Review

First, it is reasonable to distinguish tax avoidance from tax evasion. The main difference is between the legality of the former, when the behaviour of a taxpayer is not against the law, and the illegality of the latter [

11,

12]. Tax avoidance often results from shifts in commercial activity related to international income tax structure. For example, Clausing [

13] in her study found out a statistically significant relation between tax avoidance incentives and American international trade. Similarly, other authors, such as Buettner and Ruf [

14], confirmed a significant effect of tax conditions on the location of subsidiaries of German multinational companies. Nevertheless, the undeclared work is often associated with both tax avoidance and evasion when it comes to personal income tax and social insurance contributions. For more information, see the empirical research done by Krumplyte and Samulevicius [

15] in Lithuania. Krajňák [

16] also deals with selected aspects of personal income tax in the Czech Republic in this respect.

What usually leads to tax evasion is the taxpayer’s targeted VAT liability reduction. Unlike income tax, there is a possibility to receive an excessive tax deduction, which is why VAT is very popular for the purpose of tax evasion. The VAT evasion can be carried out only by VAT-registered companies or sole proprietors [

17]. It must be mentioned, however, that entrepreneurs and company managements are only people whose strategic decisions about committing a crime, especially tax evasion, are not always in accordance with the standard neoclassical economic model of human behaviour [

18,

19]. More about the theory of firms’ tax evasion can be found in Sandmo [

20], for instance, and the theory of risk aversion in connection with tax evasion is covered in Allingham and Sandmo [

21] or Bernasconi [

22]. Slemrod [

23] in his study points out that the main factor in tax-evasion decisions is the chance of being detected. Olsen, Kasper, Kogler, Muehlbacher and Kirchler [

24] did an empirical research among self-employed taxpayers from Austria and Germany. This research was focused on mental accounting of income tax and VAT. Mental accounting is a process of organizing financial operations, especially the entrepreneurs’ tax obligations. The results showed that the financially strapped, who are less careful and impulsive, are more willing to evade taxes. Age, sex and country of origin do not play any role.

Worth mentioning in this context is Portugal which tries to fight VAT evasion in an original way—through a tax lottery. Its citizens are encouraged or motivated to request sales invoices with their personal tax identification number so as to participate in a tax lottery. Wilks, Cruz and Sousa [

25] claim that these fiscal benefits helped decrease the VAT gap from 16% in 2013 to 12% in 2014, when the lottery was introduced. Similarly, Brazil and China introduced a tax lottery with the aim to encourage VAT compliance [

26,

27].

Another way how to reduce VAT avoidance and evasion is to decrease the VAT rates, according to Kalliampakos and Kotzamani [

28]. Their study concerning Greece suggests a reduction in the standard VAT rate from 24% to 20% and an establishment of one, reduced VAT rate of 10% applied only to selected goods and services with a socio-economic impact. The results of the study point to a VAT revenue improvement. Taxes are viewed from other perspectives, as well. For instance, there are also various opinions and suggestions on tax reforms and their impact from both the microeconomic and macroeconomic point of view. McClellan [

29], for instance, undertook research, using firm-level data on tax evasion and enforcement and macroeconomic data from seventy-nine countries, to find the effect of tax enforcement measures and tax revenue decrease on economic growth. On the one hand, decrease in tax revenues causes more funds for corporate investments, but, on the other hand, a decrease in funds for public goods and services, as well. It means that economic growth can be affected by an increase in tax revenues as well as by tax enforcement measures. McClellan therefore suggests reforms to increase tax revenues without introducing strict tax enforcement measures. However, a very important aspect, sustainability, also comes into play. Timmermans and Achten [

30], for example, examined a potential conversion of VAT or sales tax to damage and value added tax (DaVAT). Based on the results of the research, they recommend this shift as a consumption tax reform from the perspective of sustainable growth. The DaVAT is an environmental-character suggestion made by De Cammilis and Goralczyk [

31], and it is built on a differentiation of tax rates according to the life cycle of a product

Tax evasion is the most significant cause of the VAT gap, which is essentially the difference between expected and actual VAT revenues [

32]. There are several commonly used methods for the gap estimation [

33]. Nerudová and Dobranschi [

34] brought a new approach in this regard, the so-called stochastic tax frontier model. A comparison of results obtained with various methods designed for the case of the Czech Republic was made by Moravec, Hinke and Kaňka [

35]. An extreme gap came out of the study by Cuceu and Vaidean [

36] who emphasized that Romania’s VAT gap, expressed as a share of the VAT Total Tax Liability (VTTL), was 42% in 2011, the highest among the EU countries.

Carousel frauds inflict losses on both the public budget of a particular Member State and the budget of the EU as a whole. For this reason, this is a problem that has been under spotlight for quite some time. In this context, several substantial reforms to the VAT system were proposed, although their effectiveness is often questionable. One of the studies, made by Gebauer, Nam and Parsche [

37] and focused on the potential impact of three different VAT systems in Germany, showed, for instance, that their implementation would by contrast give rise to other possibilities of tax avoidance and an increased administrative burden. The negative impact of administrative burden on small and medium-sized enterprises is also stressed in Mikušová [

38].

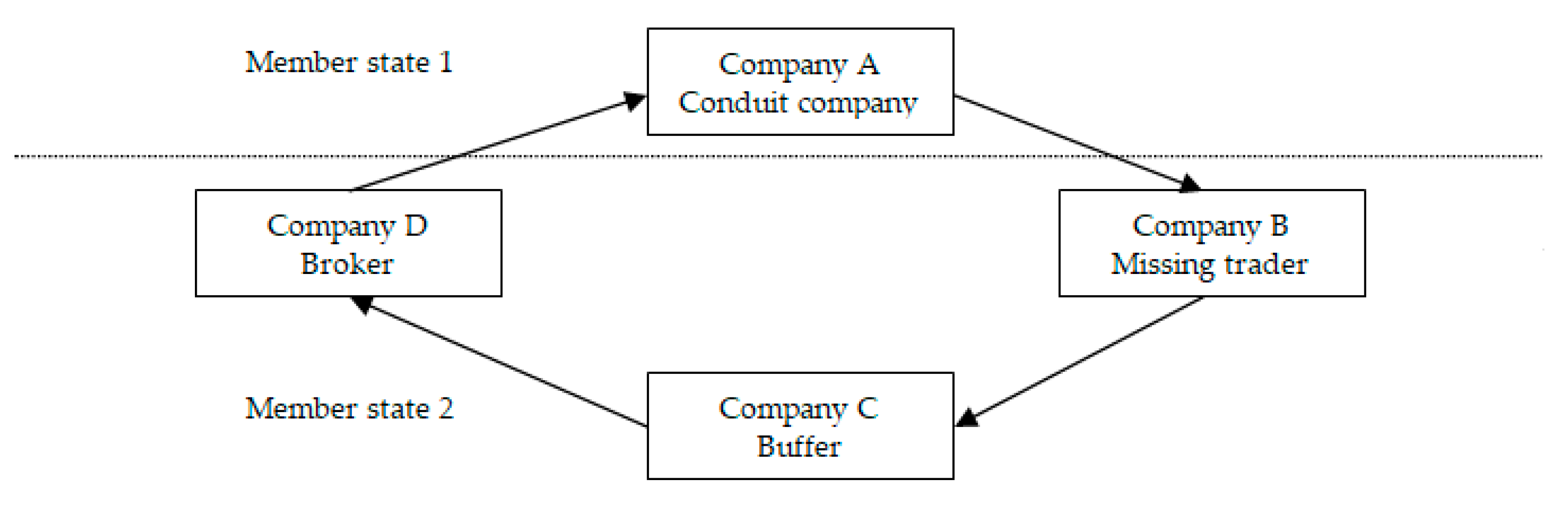

Carousel fraud or Missing Trader Intra-Community (MTIC) fraud represents a more sophisticated VAT deception [

39]. Its principle is outlined in

Figure 1. Suppose that all trade participants are VAT-registered in their countries. Initially, a Company A, the “conduit” company [

40], which is VAT-registered in Member State 1, supplies goods or the goods are supplied only fictively (the so-called “absence of actual supply”) to Member State 2, while this transaction is VAT-exempted for the Company A (zero-rated). The customer, a Company B from Member State 2, has the duty to charge the output tax from the intracommunity acquisition according to the destination principle, and at the same time is allowed to claim the input tax. This means that the acquisition from Member State 1 is tax-neutral for the Company B. The goods should be taxed by the VAT rate that is applicable in the state of destination, depending on the type of goods. In the next step, the Company B resells the commodity to a Company C, the so-called “buffer”, on its domestic market. At this instant, the Company B should charge the output tax from this domestic supply. However, in the case of fraud, the Company B does not submit the tax return and disappears (therefore the company B is called the missing trader), or submits the tax return without paying the tax liability to the tax administration. The loss inflicted on the public funds will deepen when the Company C claims the right for the input tax deduction from the invoice issued by the Company B. There can also be a great number of VAT taxpayers in the position of the buffer that may not even be aware of being part of a carousel fraud. These companies make the detection of the fraud more difficult. In the next step, another domestic transaction takes place when the Company C supplies the observed commodity to a Company D, which is yet another fraudulent company that is called the “broker“. In the end, the Company D supplies the goods from Member State 2 to the Company A from Member State 1 and the circle is closed. This intracommunity supply is VAT-exempted for the Company D. The same goods sometimes circle only fictively among the same VAT taxpayers several times [

41,

42].

Figure 1 is only illustrative, as in reality many more companies are involved in the fraud. For example, in 2016 the Financial Administration of the Czech Republic detected a fraud involving 171 domestic VAT taxpayers [

43].

The Confederation of Industry of the Czech Republic [

44] encouraged in this regard an application of the domestic RCM to metals, pointing to the decline in trade in the reinforced steel between the Czech Republic and Poland after the introduction of the RCM for this commodity in Poland. It estimated the tax losses at two billion Czech crowns.

Čejková and Zídková [

45] made another research focused generally on the impact that the introduction of the RCM for waste and scrap had had on the tax revenues in the Czech Republic. They discovered that after the implementation of the measure against the VAT carousel frauds, the trade between the Czech Republic and other EU countries had decreased, especially the intracommunity supplies. According to their calculations, the presumed volume of carousel frauds in the Czech Republic, related to waste or scrap, reached about 56 million euros/year prior to RCM.

A positive effect of the RCM on fraud reduction was also confirmed by Stiller and Heinemann [

46]. Their research was based on foreign trade data, as well, this time between Germany and Austria. To mention a non-European research initiative in this area of expertise, a poll run by Yoon [

47] among South Korean small and medium-sized dealers in copper, gold and steel scrap indicated a positive effect of RCM on trade transparency and fairness.

Similar research and poll results suggested that the RCM might be the kind of instrument the society needs in its battle against VAT evasions. As outlined earlier, the authors of the paper let themselves be inspired by these hints and decided to subject this matter to a more rigorous statistical analysis, using data on copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia and taking also into account major economic factors that may influence this kind of trade. Their analysis is elaborated in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

The Czech Republic and Slovakia rank among the countries that actively strive to inhibit tax evasion by adopting diverse legislative measures. In the time period 2006–2018 the countries introduced the value added tax control statement and reverse charge mechanism in this regard. Not long before doing so, the reported amount of export of copper from the Czech Republic to Slovakia, viewed as a time series, manifested a sudden and pronounced decline that would later turn out to be permanent. This is an interesting coincidence that provides an opportunity to confirm, or reject, that the measures were correctly designed, are functioning and should be used in practice. The confirmation can be made provided that the decline is proved to be the result of a significant change in the overall character of the time series, not just a natural fluctuation most time series are subject to, and the change was not induced by other, more natural factors, which would include the usual and major economic forces that normally affect such trades. The authors decided to analyse both whether the series did indeed experience a significant change in its development, and if so, whether such a turning point can be put down to the legislative measures and not economic or commercial reasons. This is done in the analytical part of the paper that follows.

To verify the possibility of an unexpected change in the development of the series, the authors exploited the theory of intervention models, a part of the general time series theory [

48,

49]. These models assume that the modelled series progressed in time in a certain way before a specific time point when it may have been suddenly and either temporarily or permanently shifted by an intervention to another level. If the shift is present, the development of the series is then governed by both the pre-intervention pattern and the intervention. If the intervention takes place only at one point in time, it eventually fades away and the series returns to its pre-intervention progress. If, however, the intervention acts permanently, the series still follows its pre-intervention and natural pattern, but eventually on another level. The latter case is the subject of the analysis presented here, given how the export of copper historically developed. The effect of the intervention is captured in the model by a dummy variable, which takes on value zero before the moment of the intervention and one after the intervention. Since the time series models used are usually recursive in the sense that the value of the time series is modelled as a function of its past values, the inclusion of the dummy variable will cause that the modelled value of the series is pushed eventually to another level. To be more precise, this is the case when the model parameter reflecting the effect of the dummy variable is nonzero. If it is zero, the modelled series will not move permanently to another level.

A very general model that describes the development of a time series

is of the form [

50]

Equation (1) describes the time dynamics of the series. The series depends on its past values and an additional noise , which has the properties of the standard white noise except for its conditional variance , equal to the conditional expectation of , which reflects the noise volatility as a function of the realization of the stochastic process up to time t. This volatility is not constant in time, as in the case of the standard white noise, but develops dynamically in time, as well, a feature typical of economic time series. The dynamics of the volatility is captured by (2).

The parameters

of this ARMA(

p,

q)-GARCH(

s,

r) model are estimated using the so-called likelihood function, which is a function of the parameters,

The estimates of the unknown parameters are defined as the values of the parameters that maximize

[

50]. For them to be obtained, initial values of

and

are chosen suitably, so that the recursions (1) and (2) can be used to calculate the value of

for a given set of parameters in the optimization.

In practice, log is maximized instead almost always, since this procedure is simpler, albeit still complicated as a nonlinear optimization problem, while providing the same solution. The solution is consistent and asymptotically normally distributed under general conditions, which include the validity of (1)–(3). This result allows the user of the model to perform statistical inference, i.e., hypothesis testing related to the unknown parameters and construction of confidence intervals for the parameters. The procedure is known as the maximum likelihood estimation. It is also used in the case when (1)–(3) is valid without the normality assumption, though, in which case it is called the quasi-maximum likelihood estimation. The conditions are general enough to provide the estimates with the desired statistical properties even for this no-normality case. Since nonlinear optimization is extremely complex an issue, generally speaking, the procedure must be done by a software.

The estimation and its properties rely on (1)–(3), with or without normality, and the general conditions. While it is hardly ever possible to examine the general conditions in practice, (3) is checked after the model is estimated, using the subsequent estimates of . If the properties of these estimates are in line with the assumption (3), or its generalized form without normality, it is concluded that (1)–(3) may reasonably represent the mechanisms that generated the series. This well-known statistical strategy relies on the idea that (1)–(3), with or without normality, is general enough to capture the mechanisms behind the series, in which case the proper model should yield estimates of whose properties mimick the properties of because estimates of are similar to in larger data samples under the general conditions and the properly selected model. If such estimates are not found, then either the selected model is inappropriate, or the mechanisms generating the series are so overly complex that not even the construct (1)–(3) suffices for their description. Such a pessimistic conclusion, however, is made only after many attempts to find the model failed.

The same logic is also applied to the ARMA-GARCH models enriched with exogenous variables on their right-hand side, which results in the so-called ARMAX-GARCH models. A representative of this class of models shall be used in the paper, since a dummy variable, reflecting the potential intervention, will be inserted in the model on its right-hand side. We refer to [

51] for a discussion of the potential these models have. The model will be subject to the checks in the paper.

Using standard statistical procedures, the appropriate models will show that the series on copper export underwent a historical progress that can be better mimicked with the dummy variable than without it. This suggests that the mechanisms defining the behaviour of the series before the intervention do not suffice for the proper description of its post-intervention development [

52].

The conclusion that something significant happened in the historical evolvement of the series leads subsequently to an analysis of what may have caused the shift. The analysis is carried out by going through various economic and other factors that were at work around the time of the intervention.

The analysis is data—driven. The data sources used involve mainly information from the Czech Statistical Office on cross-border movement of goods, which includes copper exports from the Czech Republic to Slovakia, information on copper properties and demand from the Copper Development Association and the International Copper Association, data from the server MINING.com on the global copper market, data from Macrotrends on copper prices, data from Trading Economics on the Slovak and the EU’s gross domestic product history, annual reports of the Czech National Bank, which keep track of the bank’s foreign exchange interventions, the real-time information on exchange rates maintained by the server Kurzy.cz and data from Agence France-Presse on the Slovak car production.

4. Results

The authors of the paper are concerned with the possibility that there may have been a factor at work in the form of an intervention that occurred in a short period of time, but had had a lasting effect, given how the series on copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia developed. This may concern specifically the intervention induced by the measure that was introduced in Slovakia in 2014 in the form of the VAT control statement. This type of reporting allows a cross-check of suppliers’ and customers’ invoices to disclose the so-called missing trader fraud, or the related carousel fraud, or the supply chain fraud. For more information about this tool, see [

53]. The intervention effect may have also been co-produced by the RCM applied to copper in the Czech Republic since 1 April 2015. That this might have been the case is suggested by the fact that such illegal trading had taken place in the Czech Republic. Fraudulent trades in copper occurred in 2012 and the Czech territory played the role of a geographic go-between in them. The trades purporting to be based on import and immediate export of copper products never happened and were reported on trade accounts of a purposefully created commercial chain in order to profit from the existing VAT mechanisms. This illegal activity was disclosed by the Czech special team Tax Cobra in cooperation with Slovak authorities through the operation called “Cupral” [

54]. Tax Cobra is represented by the Financial Administration of the Czech Republic, the Customs Administration of the Czech Republic and the Unit for Combating Corruption and Financial Crime. The team detects, identifies and combats selected tax evasion cases on both the tax and criminal side. And there were more of these cases. For more information, see [

55]. It must be said that although the Slovak measure was introduced in 2014, the country’s plans to do so were publicly known in advance, and so the traders involved in the frauds had enough time to cease their criminal activities before the measure was fully put into operation. Obviously, doing so on the day the measures came into effect or after that would have exposed them easily to justice. Thus, one might expect that the plans to restrict such trading practices could have resonated in advance on the copper market at the time prior to the drop in the exports. To verify this possibility, the aforementioned theory of intervention models was used, first to detect whether the sharp turn in the time series could at all be attributed to a new regime in its development, and if so, whether such a change could be explained by the legislative measures.

The methodology of intervention models is described in [

49,

52]. The corresponding analysis was carried out in the statistical software Stata. The entire series containing the data on copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia consisted of 149 observations [

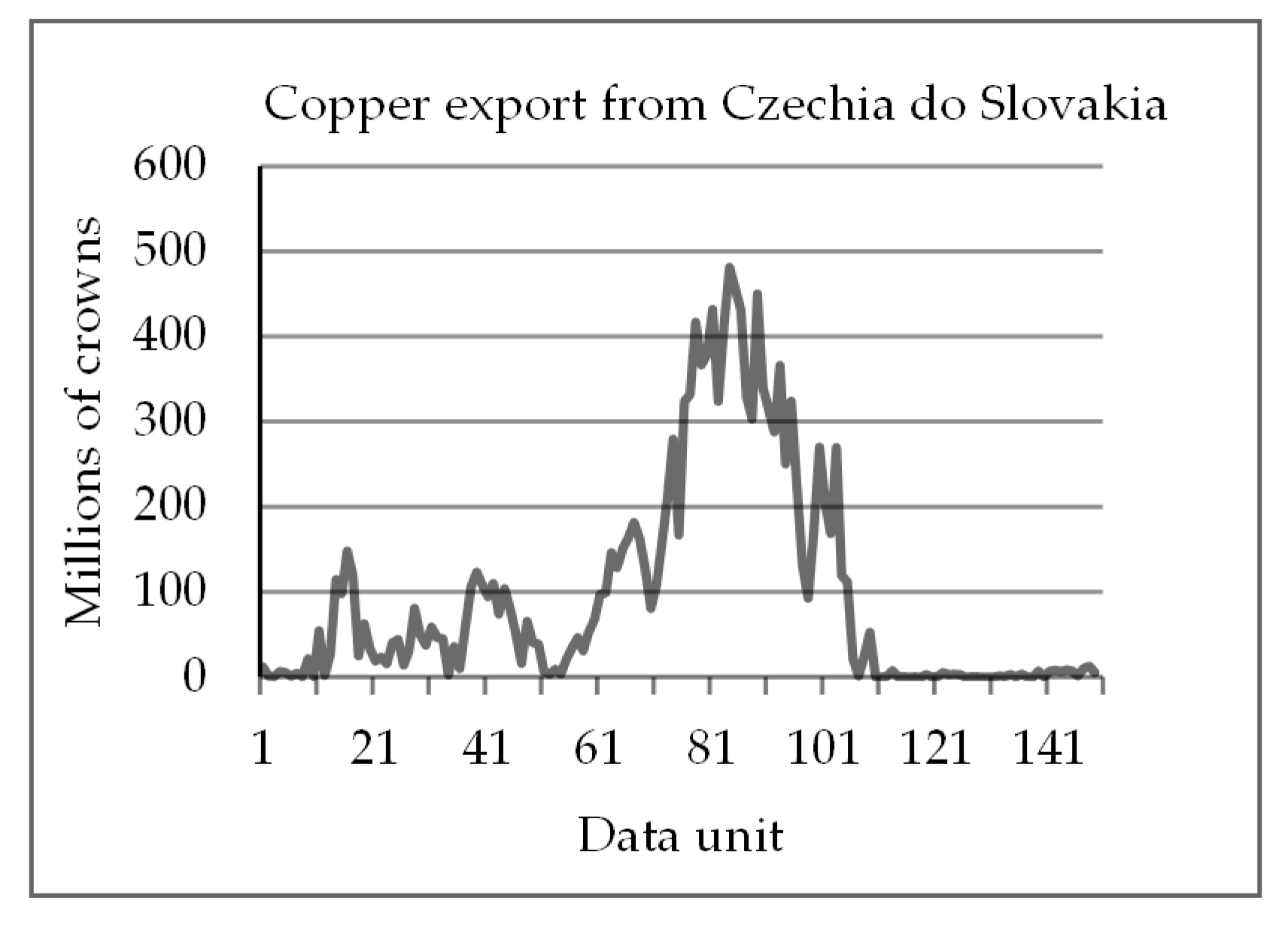

56]. It is shown in

Figure 2. The series,

, is not stationary, as is often the case in economic applications.

The point of intervention is usually unknown in intervention analyses, it is not part of the data. One way to proceed in such cases is to make assumptions about its location, using other information outside the time series data, such as the economic fundamental factors and their development. It was primarily this development that led to the authors’ opinion that if there was an intervention, the 85th data point in the series might have been the moment, when the state measures kicked in, as it was then that the series had embarked on its reverse progress, eventually accelerating its decline to the point of near disappearance, as compared to its pre-intervention levels.

To carry out the intervention analysis, standard procedures were followed. First, the pre-intervention part of the series,

, was described by an ARMA or more complex stationary model applied to a proper transformation

of the data. Once such a model was found, it was enriched with an intervention, binary variable

that took on value zero before the intervention and one afterwards. The model with

basically says that prior to the intervention the series ran as described by the pre-intervention analysis and then, after the intervention that remained in effect from that moment onward, the series still followed the pre-intervention mechanism, but was forced by

to slide to a new level where it remained, being still governed by the pre-intervention mechanism. This is after all suggested by

Figure 2.

Although the pre-intervention model should be checked for its appropriateness, it is not imperative that the check be thorough at this stage of the analysis, because the model serves only as a hint as to which model could potentially be used for the entire series. The model for the whole series must then be checked thoroughly, however. Therefore, in the pre-intervention analysis, the authors used only some of the tools to show what led them subsequently to first models with for the series.

Regarding the pre-intervention procedure, a transformation of the corresponding series,

, which would make the series stationary in the mean and variance, was searched for in the first step. To do so,

d was set to 1 and transformations of the form

,

, were analysed.

T was to stabilize the fluctuations in the series, therefore

a was selected so that

was minimized. The result was

with

. The series

is shown in

Figure 3.

The augmented Dickey-Fuller test without deterministic trend and with maximum lag of five, provided by Stata, returned the value

for the test statistic and the critical values

,

, and

at one, five and ten per cent significance levels, respectively. Thus, assuming at this early stage that the transformed data are a realization of a stationary process, autocorrelations (ACF) and partial autocorrelations (PACF) were calculated for the transformed series (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

Using 99% bands, the ACF and PACF turned out to be significant only at lag one. In theory, MA(1) processes have a significant ACF spike at lag one only (this case), while the PACF converges to zero only eventually, and monotonically on the negative side if the true MA(1) model coefficient is negative. However, a true MA(1) process of length less than one hundred values with a negative coefficient can easily be generated, where the PACF spike at lag one is significant, whereas the other PACF spikes are insignificant and appear on both sides of the x-axis (the case here again). A similar statement can, nevertheless, also be made about the autoregressive processes. Therefore, given that only a data sample was available and the ACF seemed “cleared up” to a slightly greater extent, a decision was first made to try to model the transformed and stationary series with an MA(1) model.

The estimation of the MA(1) model resulted in an equation

,

, with a

p-value of 0.003 for the MA coefficient. The Portmanteau test for the white noise yielded

p-values of 0.8–0.9 for lags 10–20. Thus, the model passed successfully introductory controls. As mentioned earlier, this was a preliminary analysis, the purpose of which was to find an outline of the model that could be employed for the whole series later on, therefore further analysis of this preliminary model was not pursued at this stage. It could already be said, however, that if the model was reasonable, then

,

,

c a constant, could be considered as a model for the whole series, and in that case, the expression

, calculated for

, should constitute a series that resembles random fluctuations

around the element

. Such a visualization was in fact made to determine what the intervention term might look like.

Figure 6 shows the remaining 65 values of the series

, i.e.,

for

.

It can be seen from

Figure 6 that the fluctuations occurred around a constant, so it made sense to set

equal to

, where

was an unknown constant and

for

t 85. The fluctuations, however, did not exhibit the sought-after constant-variance property, as shown in

Figure 6 but rather some dynamics in time. That this was the case indeed shall be seen in what follows.

Turning the attention now to the more important analysis of the whole series , employing the intervention variable , a model of the form , , c a constant, was put to use and analysed in the beginning. Let us repeat that for t < 85, for t 85 and the objective was to determine whether the parameter could be deemed statistically significant. But to do so, appropriateness of the model had to be checked first, of course.

The model was estimated as

with

p-values 0.00 and 0.029 for

and

, respectively, and with Portmanteau’s

p-value for the white noise above 0.9 for lags 10–20. The Shapiro-Wilk test of the white noise normality and the normality test based on the skewness and kurtosis gave

p-values of 0.22 and 0.17, respectively, at five per cent significance level. All these results were promising, however, the Engle ARCH-LM test returned a

p-value of 0.0002 for 6 lags used in the test and 0.007 for 15 lags. This strongly suggested, both for fewer and more lags, that conditional heteroscedasticity was present in the data, as was already outlined in

Figure 6. Therefore, further attention was paid to models of MA(1)-GARCH(

p,

q) type. In this context, the discussion about a trade-off encountered when the Engle test is used either with fewer lags or more lags sometimes follows. The former tends to accept the null hypothesis of no GARCH effects in the data, risking that if there are such effects at higher lags, the test may not be able to detect them. On the other hand, performing the test with more lags tends to reject the hypothesis, having the advantage that it can pick up effects present at higher lag but having the disadvantage that its power is lower. The authors opted for the former scenario, using five lags, since autocorrelation functions of squared residuals did not suggest presence of GARCH effects at higher lags for the models.

Compared were models of the MA(1)-GARCH(

p,

q) type, where

, including the ones where not all ARCH and/or GARCH terms were necessarily present. For instance, the model not containing the lag-one ARCH term and the lag-one GARCH term, but having more lagged terms was analyzed too. There are 42 such models altogether, although the models with many parameters could not be usually estimated by the software due to numerical complexities involved in the corresponding optimization. After the analysis, models that satisfied a set of conditions were of primary interest. The conditions concerned the model parameters and the estimates

, where

are estimated residuals from the mean equation and

is the estimate of the standard deviation of

conditioned on the entire history of the process, i.e., of

. As is known, the GARCH family of models is built around the assumption that

’s are independent and identically distributed. If this assumption is correct, it should be reflected in the properties of the estimates

[

57]. The conditions for comparing the models were: (1) All parameters in the model, except for the constant term at the worst, are significant at least at 10% significance level; (2) the

’s have a low Portmanteau statistic, or a high

p-value; (3) the

’s also pass the Engle ARCH-LM test (sig. level of five per cent, number of lags equal to five); (4) there is a suggestion that the

’s could be normally distributed based on the Shapiro-Wilk test applied to the

’s.

Condition 1 represents the natural principle of parsimony, whereas condition 3 helps determine whether the ’s can be considered independent, as requires by the GARCH theory. This was supported by conditions 2 a 4 because strong suggestions of no correlation among the ’s outlined by the Portmanteau test and their normality indicated by the Shapiro-Wilk test imply independence of the ’s. Of course, it would have been better to apply such tests to the ’s, had they been known, but they are never known, and so only their estimates could be used.

As is usually the case in statistics, more models can turn up that satisfy all the conditions. The case here was no exception. Therefore, two rounds of model selection took place in the analysis. In the first round, estimable models satisfying the four conditions were considered. Of them, the ones with a strong case regarding conditions 2–4 were selected in the second round. If there was still no clear winner, the optimized log-likelihood value was observed too.

The following

Table 1 contains MA(1)-GARCH models with the intervention variable

S that passed the first selection round, together with the ARCH-LM (number of lags equal to five, sig. level of five per cent), Portmanteau (number of lags equal to 15) and Shapiro-Wilk (sig. level of five per cent)

p-values. Around half of the models could not be estimated due to too many parameters and the flatness of the log-likelihood response surface. The software did not return any values. Ten models contained insignificant parameter(s) and three models did not pass the ARCH-LM test.

Looking at the

Table 1, models 2, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 10 are not very convincing as regards the ARCH-LM test. Of the remaining models, models 1, 3, 4 and 9 represent a strong case as far as the conditions 2–4 are concerned, although model 1 is slightly weaker than the others in the Shapiro-Wilk test. Models 3, 4 and 9 are otherwise very similar for the two observed conditions 2 and 4. The log-likelihood values at the optimum are

,

and

, respectively, for the three models. The log-likelihood value of model 1 is almost identical to that of model 3.

Given the just-presented analysis, it is the authors’ belief that of the listed models, models 3 and 4 are the best ones for description of the mechanism that generated the time series on copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia. The following

Table 2 and

Table 3 provide more details on the two models (Stata output).

To summarize, we get Model 3

with a

p-value of 0.005 for the variable S. Also, we obtain

p-values of 0.8, 0.96 and 0.67 from the Engle ARCH-LM test, the Portmanteau test and the Shapiro-Wilk test, respectively, for

. The maximum of the log-likelihood function is

. We also obtain Model 4

with a

p-value of 0.083 for the variable S. Further, we have

p-values of 0.93, 0.92 and 0.76 from the Engle ARCH-LM test, the Portmanteau test and the Shapiro-Wilk test, respectively, for

. The maximum of the log-likelihood function is

.

To get more support for conclusions, the whole procedure was also performed by replacing the MA(1) term in the mean equation with the AR(1) term, the rest following the same rules, and separately by adding the AR(1) term to the MA(1) term in the mean equation, as well. In other words, more than a hundred and twenty models containing the variable S were tried. Whereas the models of the form ARMA(1,1)-GARCH(·) had too many parameters, or did not meet other conditions, the best model among those of the form AR(1)-GARCH(·) was the model M

with a

p-value of 0.01 for the variable

S (see the

Table 4 below) and

p-values of 0.74, 0.95 and 0.81 from the Engle ARCH-LM test, the Portmanteau test and the Shapiro-Wilk test, respectively, for

(not shown here). The maximum of the log-likelihood function was attained at

.

Looking at these results, three models were obtained which are similar in many respects, one being slightly better than another in one property, while slightly worse by other criteria. Two of the three models speak strongly in favour of significance of S, the variable of interest, given its p-values. One model, Model 4, suggests significance only at ten per cent significance level, or stated more conservatively, is not entirely conclusive, not ruling out significance of S, though. In the case of Model 4, the 95% confidence interval for the coefficient of S also turned out to be , being far from symmetric around zero. All three models passed comfortably major statistical checks.

Overall, the evidence from the hard data and past behaviour of the economic fundamental factors clearly tip the balance in favour of the conclusion that the variable S played an important role in the historical development of the series. In other words, an external mechanism probably had a say in how the series would eventually develop. This, of course, supports what was already suggested in previous studies, but it should be stressed that those studies did not perform the presented type of analysis.

Now that it seems the time series changed its nature abruptly at the beginning of 2013, the question arises what may have been behind this change.

The first thing that comes to mind is that fundamental factors must have been heavily at work, to the disadvantage of the export. The factors, however, spoke to the contrary. Let us take a closer look at them, one at a time. Starting with the exchange rate of the Czech crown, it was depreciating against the U. S. dollar and euro around the time in question. In 2013, the currency started its slow but continual decline, which later even picked up speed [

58,

59]. One would expect that this had played in favour of the copper export. It became clear over time that the Czech National Bank intervened to an unprecedented extent to keep the crown weak and support domestic exporters. In the years 2013–2017 it bought euros worth around two billion crowns [

60]. However, these efforts failed to stop the sharp decline in the copper export from 2013 onwards.

The overall economic development in the region is another factor worth mentioning, as there is a strong relationship between that and the copper demand, given how important the metal is. Copper is an excellent electric and heat conductor and is resistant to corrosion, i.e., it is highly durable [

61]. These properties boost its attractiveness in the times of increased pressure on energetic efficiency and overall product durability and environmental protection. For these reasons, copper has been known for long to be present in many industries. Sometimes, it is even considered as another measure of economic growth, alongside GDP. One could therefore speculate that around 2013 there might have been a broader economic slowdown that damped down the export from the Czech Republic to countries like Slovakia. Again, this was not the case—the Slovak growth was accelerating at that time, as was the case in the entire EU, to give a bigger picture as is shown in

Figure 7a,b [

62,

63].

Besides, there should be a longer-term interest in copper because of the efforts to expand production of electric and robotic vehicles, regardless, to an extent, of economic growth. It is a known fact that more copper is needed to produce these cars than the traditional fuel-powered ones. For plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, the amount of copper needed is 2.6 times as high, for battery electric vehicles it is approximately 3.6 times higher [

64]. Moreover, Slovakia is the world’s largest producer of cars per capita [

65]. To give yet a bigger picture of the interest in copper, in 2014 the global demand for copper reached a record 27 million tons in spite of the then damped global economic situation [

66]. This again shows how important the metal is.

When it comes to copper pricing, another economic factor, since 2013 it had been in a decline, having left a climax in 2010 [

67], see

Figure 8. If not exactly in 2013 or soon after that, at least in later years lower prices could have been reflected in the copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia. This did not happen, however.

Last but not least, the amount of copper produced might be another factor. There were reports that copper had not been supplied in sufficient amounts [

68,

69], but these reports followed what had been demanded. A comparison of what is produced and what is demanded is one thing, the production extent in itself is quite another. It is true that relative to what is desired in the copper market, the supply of the metal has been lagging behind, but its production has been steadily rising for decades [

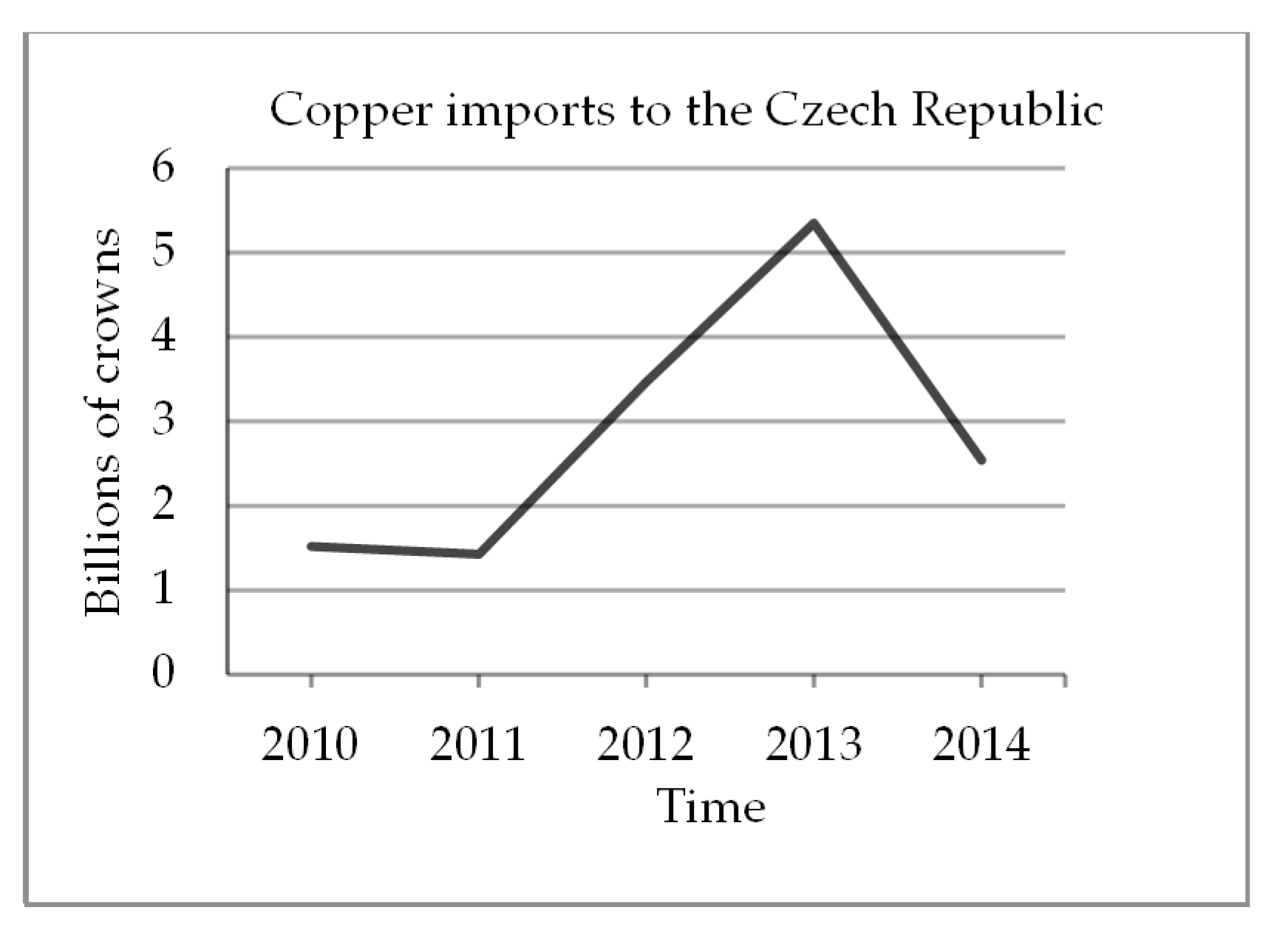

70]. We cannot therefore conclude that there has been less and less copper on offer. The opposite is true actually, it just still isn’t enough given what is demanded. When it comes to the Czech Republic specifically and its copper production, although copper mines exist in the country, the production is so small that it is not even listed in various statistical tables published by copper-oriented agencies and institutes. Thus, the emphasis is placed on copper imports to the country, the recent history of which is shown in

Figure 9 [

56].

The amount of copper imported to the country had been rising for several years prior to 2013, and so it is hard to imagine that copper happened to be in severely short supply locally.

Table 5 contains the data from the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic [

71,

72] and shows how the world production of the primary copper has been increasing. The data were recorded in the Mineral Commodity Summaries (MCS), a bulletin of the U.S. Geological Survey, and in Austria’s World Mining Data (WBD).

Further,

Table 6 sheds more light on the problem. Its first two lines show that the total copper import to Slovakia was to a great extent made up of the Czech copper import before the plunge occurred, yet after the plunge, the total copper import to Slovakia was far from being fully recovered. It steadied itself at around fifty percent of what it was prior to the intervention. If the copper exports from the Czech Republic to Slovakia had all been real, it would have been strange for Slovakia to allow such a drop to continue without a more pronounced replacement of it. On the other hand, it is not possible to assume that all copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia was a fictitious fraud because in that case, Slovakia would have had rather small amounts of imported copper in the pre-intervention time period, given how much the Czech import represented in the total copper import to Slovakia at that time. The answer will probably lie somewhere in between. That this is most likely the case is very strongly supported by the third row of the table which records copper imports to Slovakia from Czechia by the Slovak Statistical Office (SOSR), as compared to the second row of the table representing these trades, as recorded by the Czech Statistical Office (CZSO). There is a striking difference in these numbers, even though they concern the same cross-border movement of the same commodity. The explanation might be the fact that exporters declare what is VAT-exempted, whereas the Slovak importers might act as missing traders, not declaring these supplies, which plays to their advantage. For the explanation of the term “missing trader”, see

Section 2 and

Figure 1. Such findings were also made by Čejková and Zídková [

45]. This may also be the explanation why in 2013, the total copper import to Slovakia was smaller than that from the Czech Republic. Based on these data, there is a good chance that not a small amount of the copper imports to Slovakia from the Czech Republic represented fraud, and fundamental economic factors are of no importance to such trades.

Last but not least, according to the CZSO [

56], the copper export did not seem to shift from the Czech Republic to other countries either, as a substitute for Slovakia, because that export dropped, as well, see

Table 7. Interestingly enough, the reverse charge mechanism on this commodity was introduced also in other neighbouring states, such as Austria and Poland.

To sum up, it is difficult to find a single major economic or commercial factor that would explain satisfactorily why the copper exports from the Czech Republic to its neighbour took a sharp turn at the beginning of 2013 and then shrank permanently.

The only major external mechanism conceivable at that time were the two measures planned by the Czech Republic and Slovakia in their fight against VAT frauds.

5. Upcoming and Proposed Changes in the VAT Rules within the European Union

As we have seen there is a good chance that the special tools such as VAT control statement and RCM make sense in the battle with tax fraudsters. This section covers other steps taken or proposed by the EU bodies, and comments on their strengths and weaknesses. After all, the studies presented in this paper, as well as the European Commission’s actions, showed that VAT evasion is a pressing problem that cannot be overcome by a simple solution. It needs a number of systematic measures.

Following the results of the public consultation “The Green Paper on the Future of VAT” [

74], the European Commission prepared “The Action Plan on VAT” [

75]. The plan contains proposals that aim to improve tax collection, introduce additional instruments to combat tax evasion, reduce administrative burden on SMEs in B2C transactions, improve efficiency of tax administration and modernize VAT rates. After the adoption of the plan, the European Commission approved several directives and prepared a number of other proposals in this field.

First, in line with the topic of this paper, it is necessary to mention the proposal of a definitive VAT system for intracommunity B2B transactions. This system, which could come into effect in 2022, means that goods would be taxed in the Member State that is its final destination. In relation to the system, the institute of certified taxable person (CTP) would be established. The adoption of the system would not bring any changes to the current procedure for CTPs whose partners are CTPs from other Member States. The customer would still be liable to collect VAT on the reverse charge basis. However, this institute would be granted only to VAT taxpayers who meet relatively strict conditions. For more information on them, see [

76]. It is obvious that this change may negatively affect SMEs. The reason is that unlike CTPs, VAT taxpayers without the certification would have to pay the tax in the destination state at the rate applicable in that country through the “One Stop Shop”. On the one hand, the “One Stop Shop” system is a facilitation because the supplier pays the tax liability to all states with one payment in his home state. On the other hand, the supplier must always check the VAT rate, which is applicable in the country of destination, for each delivered commodity. At the same time, the recapitulative statement would be cancelled, which would complicate the work for tax authorities because they would lose information about individual intracommunity supplies. This situation may favour VAT evasion on a different basis.

A very important aspect is the extension of the possibility of applying the aforementioned instrument in the fight against tax evasion, the RCM. Application of this measure is prolonged until June 2022, and is governed by Council Directive (EU) 2018/1695 of 6 November 2018, amending Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of value added tax as regards the period of application of the optional reverse charge mechanism in relation to supplies of certain goods and services susceptible to fraud and of the Quick Reaction Mechanism against VAT fraud [

77]. The previous RCM directives, especially Council Directives 2013/42/EU [

78] and 2013/43/EU [

79], were effective until 31 December 2018.

Moreover, due to the magnitude of carousel frauds, some Member States including the Czech Republic and Slovakia called for a solution that would not limit the scope of commodities and services for the RCM and would therefore simplify the application of VAT in domestic supplies. This is why the European Commission approved Council Directive (EU) 2018/2057 of 20 December 2018, amending Directive 2006/112/EC on the common system of value added tax as regards the temporary application of a generalised reverse charge mechanism in relation to supplies of goods and services above a certain threshold [

80]. However, each Member State has to meet several criteria according to the Article 199c of the VAT Directive in order to apply for the implementation of the generalized RCM (GRCM). The mechanism will be applied to domestic supplies of goods and services above the threshold of 17,500 euros per transaction. Of course, in relation to this limit, the Member States should prevent the potential circumvention of the GRCM by artificially splitting the taxable amount of the taxpayers’ transactions. Fortunately, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are among the countries that are able to monitor this potential new way of VAT fraud via the VAT control statements. In any case, implementation of this measure can lead to migration of carousel frauds to other Member States that cannot implement the GRCM and can generate a negative impact on the internal market. Therefore, the neighbouring countries will be able to apply this system even if they do not meet the criteria based on the Directive 2018/2057, as it is clear that the frauds would move to their area. The Czech Republic has already obtained a permission for application of the GRCM from the European Commission and an approval of the European Council. Unfortunately, the measure can be applied only for a short time period, from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2022. For this reason, the Czech Republic has not incorporated this tool in its legislation and decided to seek its prolongation [

81].

On the one hand, the GRCM seems to be a suitable tool to tackle VAT evasion. On the other hand, it is still obvious that it could bring complications to companies, whose business partners are both VAT and non-VAT payers. It could increase administration costs and scope for mistakes caused by improper case-specific application of this system. In addition, it can cause problems in business activities that are VAT-exempted, such as certain financial or insurance services.

Also, the RCM has not been proved to be quite effective in combating VAT fraud in Poland, for instance. For this reason, the measure was replaced in the country by the mandatory split-payment mechanism, effective from 1 November 2019. This mechanism is applied to selected services and commodities, such as construction services, steel products and non-ferrous metals including copper. Involved are B2B transactions exceeding the limit PLN 15,000. The principle of the mechanism lies in splitting the payment of a transaction into a tax base and the tax. The tax base is paid to the account of the supplier that is commonly used for business and the VAT is deposited into a separate VAT account. This special account is used only for the payment of VAT liability to the tax administration [

82]. Nevertheless, this system has been voluntary since 1 July 2018 in Poland and since 1 April 2011 in the Czech Republic [

83]. The main disadvantage of this system is an increase in compliance costs. In addition, the conclusions of a study made by Stoicea and Iorga [

84] show a negative impact on insolvent agricultural companies due to their reduced chance of recovery. In Romania, the system has been mandatory for state companies and companies in insolvency since January 2018. Poland also introduced another measure in its fight against carousel frauds, the STIR-Information System of the Reconciliation Chamber, in effect since 1 January 2018. It is a software that enables us to detect the risk of fiscal-fraud occurrence. The system requires financial institutions to provide data for analysis to the Polish tax administration. For more information about the tool, see, e.g., [

83].

The so-called “quick fixies” is also worth mentioning in this context. These are measures to improve the VAT system for intracommunity supplies of goods. Changes in the system are regulated by Council Directive 2018/1910 of 4 December 2018, amending Directive 2006/112/EC as regards the harmonisation and simplification of certain rules in the value added tax system for the taxation of trade between Member States [

85]. The Directive regulates intracommunity supplies under call-off stock arrangements and supplies of goods in the chain. The EU Member States shall apply those provisions from 1 January 2020.

In any case, talking about the development of VAT rules, the EU cannot be isolated from the rest of the world. This approach could cause double taxation or no taxation, especially in the case of cross-border supply of services and intangibles. Therefore, several chapters of “The International VAT/GST Guidelines” were adopted in more than 100 countries [

86].

6. Discussion

Based on the results of the statistical analysis presented in this paper and other European Commissions’ planned steps, the authors’ favour the view that one of the more appropriate options in the fight against tax evasion is the introduction of the GRCM that Member States will be allowed to apply from 1 January 2020. It seems that the Czech Republic will be one of the pioneers to fully implement this system. However, such measures should be implemented in the Member States simultaneously, regarding both the time frame and the range of commodities and services. Moreover, differences exist in the limits for applying the scheme in individual Member States. This means that tax evaders have tendency to artificially divide their supplies so that they get under the financial limit, and the regime does not apply to them. They can then use the classical input-output VAT regime. The mismatch specifically arises when one of the states sets a limit for the application of the scheme and a neighbouring state applies that scheme without a billing threshold (e.g., the Czech Republic and the neighbouring Slovakia). Generally, differences in the implementation of the regime in individual countries help move these frauds to states where the regime has not been put into practice.

The results of the analysis imply that the common VAT system, currently applied in the EU, is not sustainable and requires reforms. It is necessary to emphasize, however, that all countries should prepare significant legislative changes in accordance with the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The Czech Republic included required sustainable-development goals in its document Strategic Framework Czech Republic 2030. The document, among other things, contains a SWOT analysis which mentions a simple, transparent and predictable tax system as one of its opportunities and generally high administrative burden as one of the weaknesses [

87].

Notwithstanding, according to the authors, the new system proposed by the European Commission, the introduction of the CTP including a de-harmonization of VAT rates, could lead to the opposite situation. It could lead to uncertainty regarding application of correct VAT rules, which could distort the internal market, increase the administrative burden on businesses and cause difficulty in identifying and verifying information on trading partners that are often not up to date. Implementation of these principles would have a negative impact on the small and medium-sized enterprises that do not have sufficient financial and time resources to verify such information.

Also, it should not be forgotten that despite the fact that many other research studies mentioned in the theoretical part of the paper confirmed a positive effect of the RCM, Poland, another neighbour of the Czech Republic, happened to find out that it might not be so strong a mechanism by itself as was expected, which is why the country established the split-payment mechanism. This means that the payment is split into a tax base and VAT. The VAT is sent to a special account and then passed on to the tax administration. The obligation is valid both for the companies residing in Poland and the companies residing in another country, but registered for VAT in Poland. The system is applied in Poland only to selected goods and services. In the authors’ opinion, this should be applied generally. This might also be a good way to fight tax evasion. There is a possibility to use the split-payment system on a voluntary basis in the Czech Republic too. However, this mechanism is used very seldom, only in the cases when the customer has a reasonable fear that the supplier will not pay the VAT to the tax administration. It must be noted that the supplier has to agree with the application of the mechanism. The administrative burden and related compliance costs are also very high. Another disadvantage of the split-payment system is that the system can bring liquidity problems to businesses whose inputs are taxed with a standard VAT rate, while their outputs are subject to a reduced or super-reduced VAT rate. In the Czech Republic, this is the case of the construction industry, especially social housing. Last but not least, due to the important impact on cash flow, the system could have negative effect on insolvent entities.

Another tool that could inspire the Czech government or other Member States is the Poland’s IT system STIR. STIR is able to analyse data on money transfers among bank accounts used by businesses and detect organized criminal activities on the fiscal basis. Even if the system works relatively automatically, there is some threat, though, that financial institutions will compensate the increase in compliance costs by raising their own fees.

Based on the results of this study, the authors recommend an introduction of several measures against tax evasion at the same time, or in a short time frame, in order to multiply their effectiveness. The truth is that the actual effectiveness of the measures can only be assessed retrospectively, which is in fact what keeps pushing the VAT system out of its steady state.

Moreover, it is obvious that COVID-19 will have a very negative impact on the economy and will deepen state budget deficits. Nowadays, tax evaders have more opportunities for frauds, as activities of Tax Administrations related to control mechanisms are limited. The EU should unite and agree on tools in its fight against tax evasion that could help decrease the fall in tax revenues and encourage sustainability of public budgets.

The future research of the authors could be focused on the effect of COVID-19 on tax revenues and occurrence of the VAT evasion within the EU.

7. Conclusions

Since public administration systems can function properly only if they are capable of collecting taxes, it is of paramount interest to have mechanisms in place that will effectively restrain room for tax fraud. This specifically concerns the value added tax, which is by nature a very popular instrument among law offenders. Countries that have experience with this kind of law violation are forced to adjust their legislation in order to curtail such exploitation of the legal system, although the extent of functionality of the changes is not easy to identify in advance, or even guarantee, given the slyness of those who participate in the shadow economy. The legal adjustments should therefore be subject to analysis, not only before, but also after being put into use, to see if they truly act as a deterrent.

This paper seized the opportunity to do so in the case of the Czech Republic and Slovakia because copper export from one country to another is known to have been abused by tax criminals in the past, and also because those trades showed a sudden and steep drop in their historical development, coincidentally around the time when the countries were readying to launch new legislative measures to fight tax evasion. This is mainly the reason why the analysis was performed in the paper, since it is very tempting to link unadvisedly an abrupt change in a time series development to a newly appearing factor—a legislative measure, which are in this case the VAT control statement and reverse charge mechanism. There are two problems when such a link is hastily established. Firstly, it cannot be ruled out that the time series development, covering the time period both before and after the drop, remained natural because of the character of all the economic factors that normally affect it. These factors would not have included the legislative measures, and they would not have changed fundamentally their own behaviour. Simply put, it could suffice to utilize the economic factors alone and their natural character, radically unchanged, to explain the development of the copper trades no matter how dramatic it seemed to be. Secondly, even if there is a suspicion that circumstances changed radically, it is not immediately obvious and guaranteed that it must have been the legislative or government measure that caused the steep decline in the copper trades. It could have been one of the economic factors. These are two strong reasons why the phenomenon should be analysed in greater detail.

The paper analysed the problem, using the theory of intervention time series models and a breakdown of fundamental factors that have the potential to change radically the historical development of trading habits. An intervention model considers the idea that the observed series might have followed a pattern to a certain point in time, which raises suspicion because it is a point of abrupt change in the series, and then started to shift, eventually ending up following the same pattern on another level. In order for the model to be more able to copy such shifts, a special variable is inserted in its equation. Subsequently, the significance of the coefficient belonging to the variable is tested statistically, i.e., it is tested whether the coefficient is zero or not. If it turns out to be zero, it is concluded that the series had continued to follow the same pattern after the time point in question. Since no change in its character took place, it is assumed that no intervention was present, as the special variable acts as a switch that reflects interference. In order for this theory to work, the model describing the entire history of the series, and containing the special variable, must pass several checks in the first place. These checks establish its credibility. Once the credibility is established, it is assumed that the model describes well enough the mechanisms governing the development of the series. What then remains is to check, as mentioned, whether the special variable is also necessary for such description. In this regard, more than a hundred time series models were tried in the analysis. Three of the models passed the checks strongly, while two of them also did not allow the special variable to be removed. One model was inconclusive in this regard. This is a sound suggestion that an abrupt change in the character of the series might have taken place.

Since the results of the statistical analysis were clearly more inclined towards the conclusion that something abrupt did happen in the behavioural character of the series, the authors took up the task of detecting what had caused this change. We analysed an entire group of factors involving major economic forces, data on copper export from other countries and the legislative measures adopted by the two countries to deter criminals from trading in copper, if there were any. Looking at the official data from statistical offices and internationally recognized agencies, there is no meaning in linking the fundamental economic factors, such as copper prices, copper production, gross national products or exchange rates, to the fall that the copper export from the Czech Republic to Slovakia suddenly and permanently experienced at the beginning of 2013. Nor is it possible to say, based on the data, that other countries acted as a replacement for the Czech Republic, when it comes to exporting copper to Slovakia, or that the Czech copper export changed direction.

The authors conclude that the only rational explanation behind the sudden and pronounced drop in the copper exports can be found in the two countries’ fight against tax evasion and their corresponding legislative measures. The data not only suggest that these measures seem to be functioning, but also reveal that the copper trading between the two states was probably not meant to be real to a great extent. Although the results may not seem too surprising to some, they are data-driven far more than similar studies.

Since the analysed legislative measures have the potential to be of value, it is also worth discussing how much and in what form the European Union benefits from them. The authors provided that discussion in the later parts of the text, pointing out that the current tax system is not set up in such a way so as to utilize the measures sufficiently, and needs to be improved. We also mentioned the advantages and disadvantages of other measures introduced in other Member States, in particular the proposed definitive VAT system for intracommunity B2B transactions.